Depression in Romanian Medical Students—A Study, Systematic Review, and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Cross-Selectional Study

2.1.1. Participants and Procedure

2.1.2. Measures

- Context and socio-demographic data: A customized questionnaire was used to gather data like age, gender, year of study, faculty, marital status, living situation, parental education, exposure to negative behavioral models during childhood and adolescence, presence of hobbies, and social support;

- Depression: The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [23] was used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms over the past two weeks. The PHQ-9 is a 9-item self-report measure scored on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = Not at all, 3 = Nearly every day), yielding a total score from 0 to 27. Example item: “Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless”. Standard cut-offs were used for severity categories: 0–4 (minimal), 5–9 (mild), 10–14 (moderate), 15–19 (moderately severe), 20–27 (severe). In our sample, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88, indicating high internal consistency;

- Procrastination was measured using the General Procrastination Scale—Student Version [24], a 20-item self-report instrument that assesses tendencies toward task delay and academic procrastination. Participants rated items on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = “Extremely uncharacteristic of me” to 5 = “Extremely characteristic of me”). Sample item: “I often find myself performing tasks that I had intended to do days before.” Several items are reverse-coded. This instrument has demonstrated good reliability in academic populations; in our sample, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85;

- Personality traits: We assessed personality using the Big Five Inventory—Short Form (BFI-S) [25], which includes 15 items that measure five traits: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Each trait is measured by 3 items, with responses being given on a 7-point Likert scale (from 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 7 = “Strongly agree”). Sample neuroticism item: “I see myself as someone who gets nervous easily.” In our sample, the subscale reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) ranged from 0.68 (agreeableness) to 0.81 (neuroticism), consistent with validation studies of the short-form BFI.

2.1.3. Statistical Analysis

Data Preparation and Screening

Data Processing

2.1.4. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

2.2.1. Search Strategy and Study Eligibility

2.2.2. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.2.3. Statistical Analysis (Meta-Analysis)

3. Results

3.1. Local Cross-Sectional Study Results

3.1.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

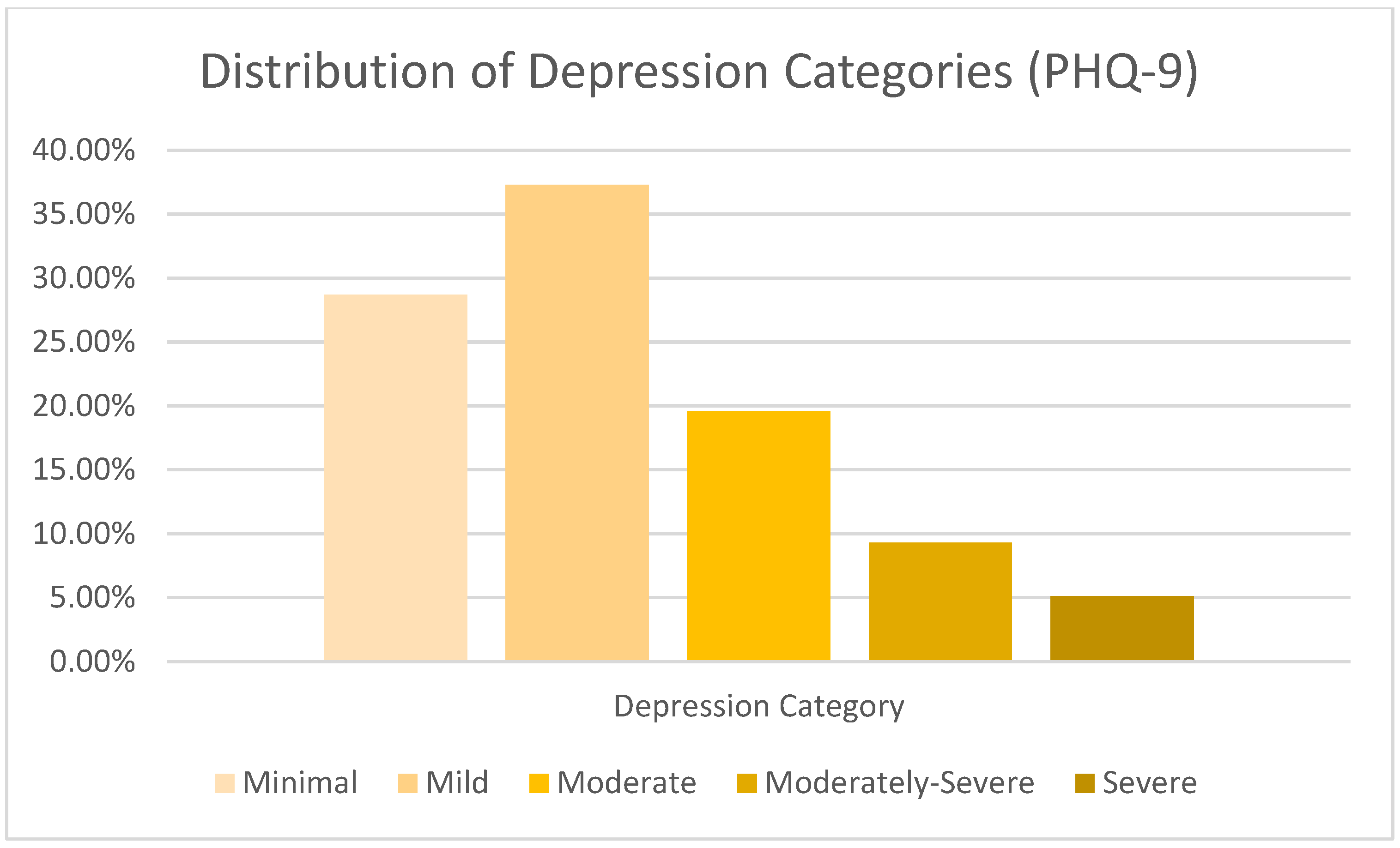

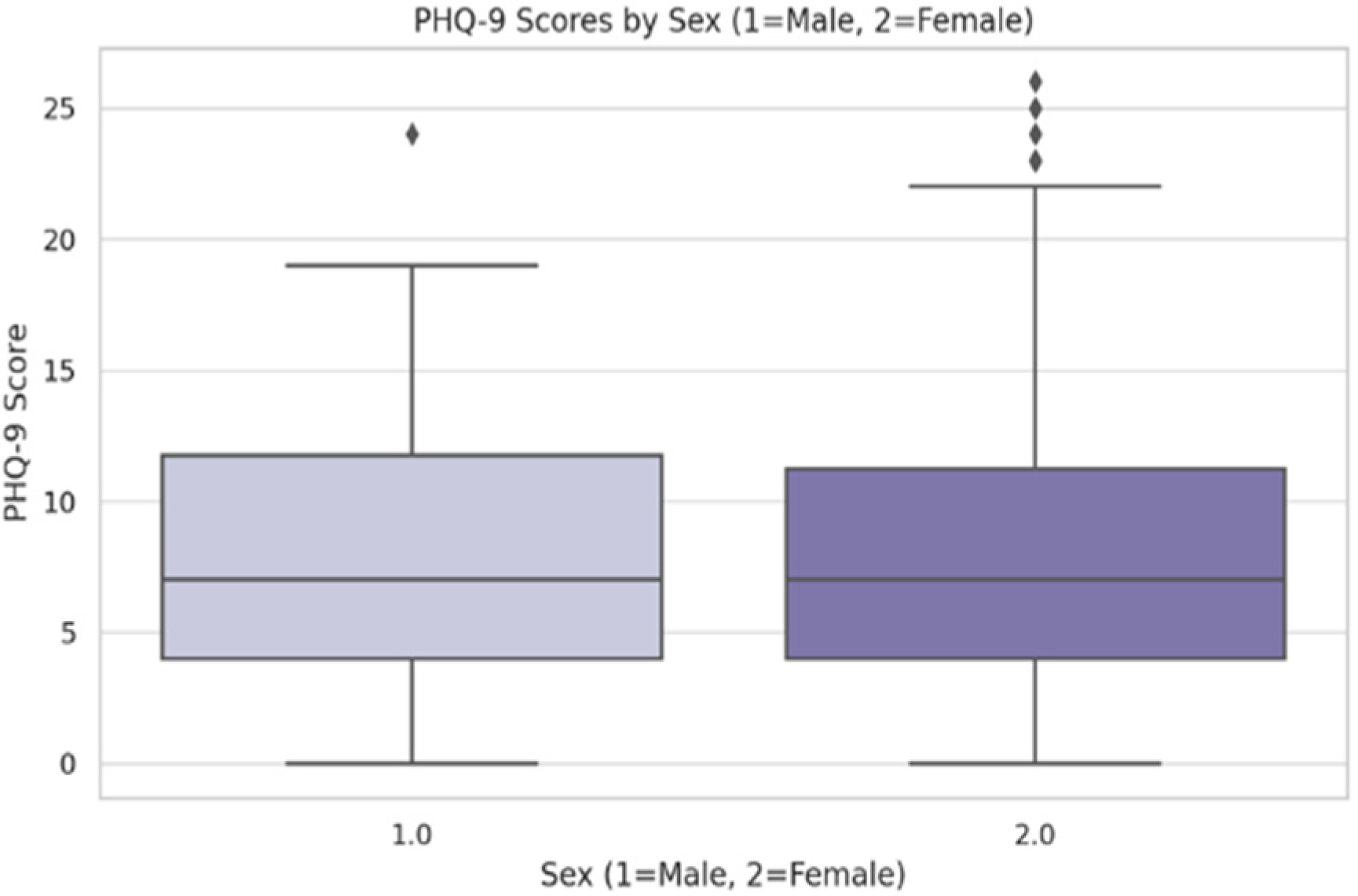

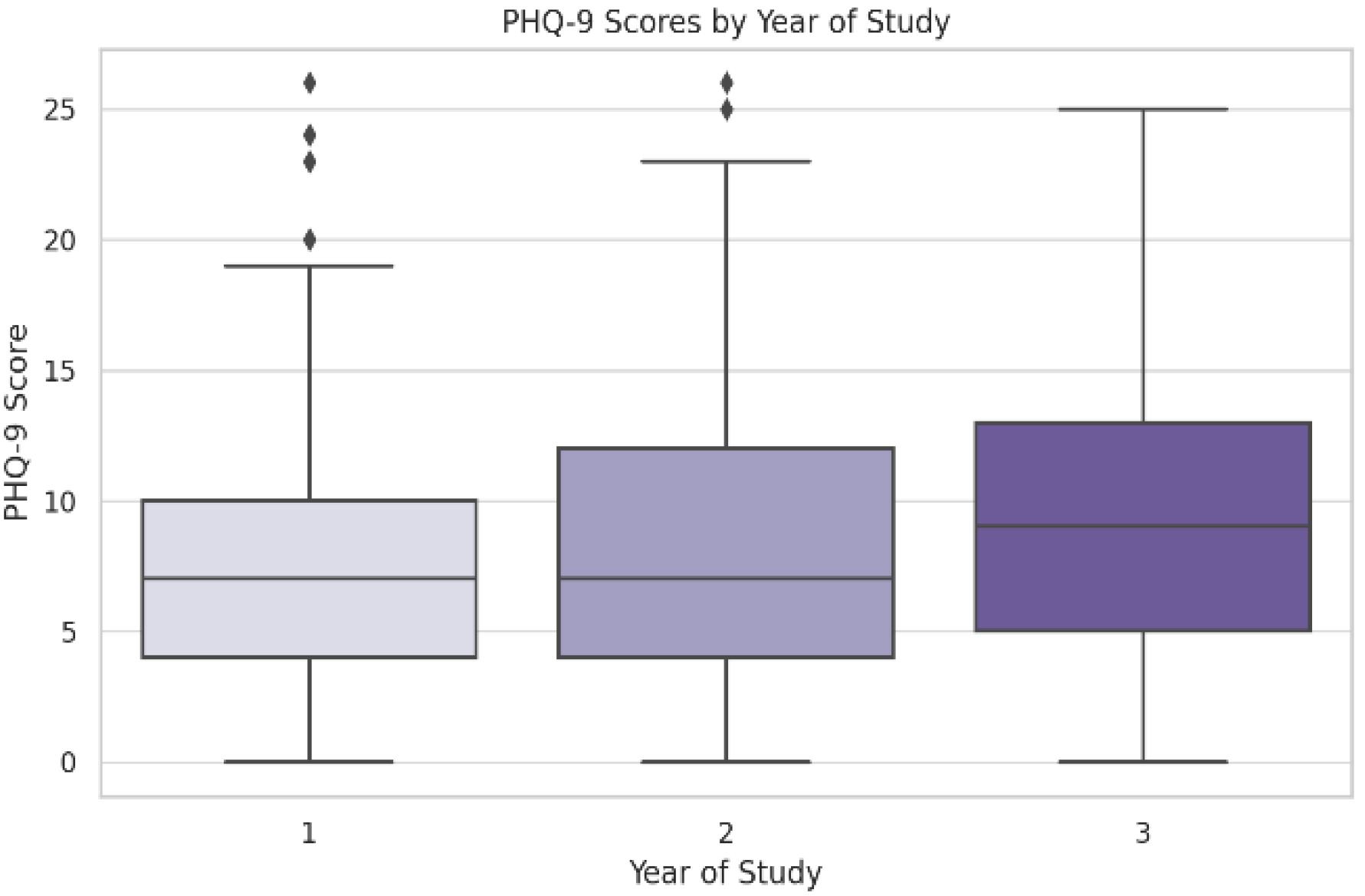

3.1.2. Prevalence and Severity of Depressive Symptoms (PHQ-9)

3.1.3. Correlates and Predictors of Depression in the Galați Sample

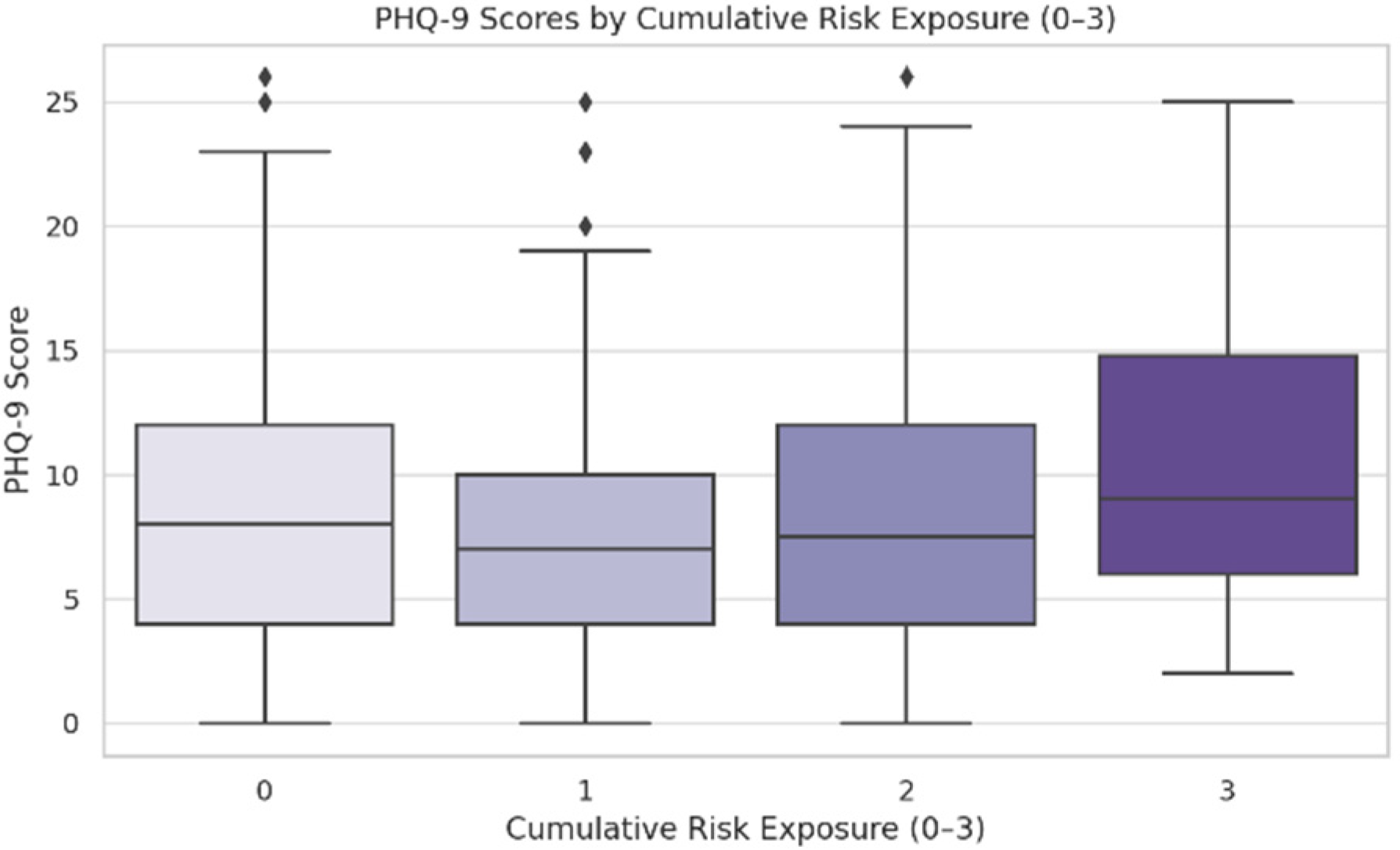

Group Differences in Depression Scores

Correlation and Regression Analyses

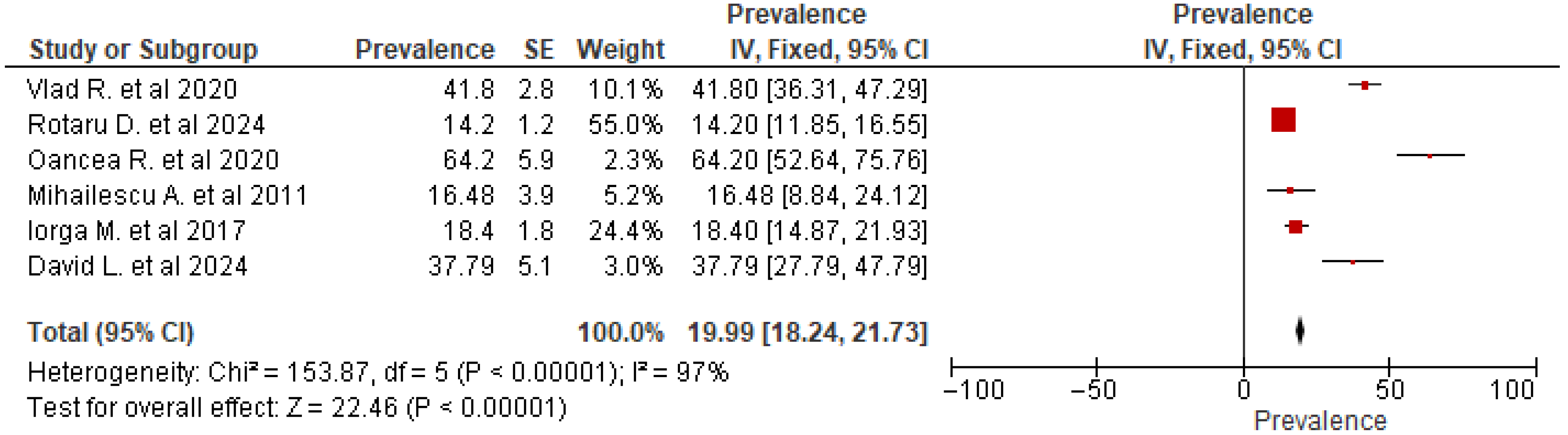

3.2. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Results

3.2.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.2.2. Analysis of Prevalence

3.2.3. Subgroup Analysis by Assessment Instrument

3.2.4. Sensitivity Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Local Sample Results

4.2. Meta-Analytic Findings

4.3. Cross-Comparison Between the Two

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| BDI | Beck Depression Inventory |

| BFI-S | Big Five Inventory—Short |

| CC BY | Creative Commons Attribution |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DASS-21 | Depression Anxiety Stress Scales—21 Items |

| HSD | Honestly Significant Difference (Tukey’s) |

| I2 | I-Squared Statistic (Heterogeneity) |

| M | Mean |

| NA | Not Available/Not Applicable |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| ZSDS | Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale |

Appendix A

| Source | Search Strategy | Articles Retrieved |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | ((((((((Depression prevalence) OR (depression symptoms)) AND (medicine students)) OR (dentistry students)) AND (PHQ-9)) OR (Patient Health Questionnaire)) OR (BDI)) OR (Beck Depression Inventory)) AND (Romania) Filters: Free Full Text | 286 |

| Web of Science | ((((((((ALL = (Depression prevalence)) OR ALL = (depression symptoms)) AND ALL = (medicine students)) OR ALL = (dentistry students)) AND ALL = (PHQ-9)) OR ALL = (Patient Health Questionnaire)) OR ALL = (BDI)) OR ALL = (Beck Depression Inventory)) AND ALL = (Romania) Filters: Open Access and Countries/Regions = Romania | 700 |

Appendix B

| No | Author/Year | Study Design | Sample Size | Ascertainment of Depressive Symptoms Measure | Representativeness of the Sample | Descriptive Characteristics of Participants | Overall Methodological Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auth 1 | Auth 2 | Auth 1 | Auth 2 | Auth 1 | Auth 2 | Auth 1 | Auth 2 | Auth 1 | Auth 2 | Auth 1 | Auth 2 | ||

| 1 | Iorga M. et al./2017 [18] | W | W | W | W | S | S | W | W | S | S | W | W |

| 2 | Vlad R. et al./2020 [17] | W | W | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| 3 | Oancea R. et al./2020 [31] | W | W | W | W | S | S | W | W | S | S | W | W |

| 4 | Rotaru D. et al./2024 [20] | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| 5 | Mihăilescu A. et al./2011 [16] | W | W | W | W | S | S | W | W | S | S | W | W |

| 6 | David L. et al./2024 [32] | W | W | W | W | S | S | W | W | S | S | W | W |

References

- World Health Organization. Depression. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD; European Union. Health at a Glance: Europe 2022: State of Health in the EU Cycle; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/health-at-a-glance-europe-2022_507433b0-en.html (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Consiliul Economic și Social (CES). Sănătatea Mintală în România: Un Tablou Integrative; CES: București, Romania, 2023; Available online: https://www.ces.ro/newlib/PDF/2023/Tabloul-sanatatii-mintale-in-Romania-2023.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Patriche, D.; Filip, I.; Tănase, C. Epidemiologia depresiei. Rev. Med. Rom. 2015, 57, 260–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balazs, J.; Miklósi, M.; Keresztény, Á.; Apter, A.; Bobes, J.; Brunner, R.; Corcoran, P.; Cosman, D.; Haring, C.; Kahn, J.-P.; et al. P-259-Prevalence of adolescent depression in Europe. Eur. Psychiatry 2012, 27 (Suppl. S1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovu, M.B.; Breaz, M.A. The prevalence and burden of mental and substance use disorders in Romania: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Psychiatr. Danub. 2019, 31, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, A.K.; Kelly, S.J.; Adams, C.E.; Glazebrook, C. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Ramos, M.A.; Torre, M.; Segal, J.B.; Peluso, M.J.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2016, 316, 2214–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, D.A.; Ramos, M.A.; Bansal, N.; Khan, R.; Guille, C.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Sen, S. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2015, 314, 2373–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puthran, R.; Zhang, M.W.; Tam, W.W.; Ho, R.C. Prevalence of depression amongst medical students: A meta-analysis. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quek, T.T.-C.; Tam, W.S.; Tran, B.X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Ho, C.S.-H.; Ho, R.C.-M. The global prevalence of anxiety among medical students: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Thomas, M.R.; Shanafelt, T.D. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad. Med. 2006, 81, 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, M.S.B.; Abdul Rahim, A.F.; Baba, A.A.; Ismail, S.B.; Mat Pa, M.N.; Esa, A.R. The impact of medical education on psychological health of students: A cohort study. Psychol. Health Med. 2013, 18, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlin, M.; Joneborg, N.; Runeson, B. Stress and depression among medical students: A cross-sectional study. Med. Educ. 2005, 39, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihăilescu, A.; Matei, V.; Cioca, I.; Iamandescu, I. Stresul perceput-predictor al anxietății și depresiei la un grup de studenți în primul an la medicină. Pract. Med. 2011, 6, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Vlad, R. Depression and anxiety in Romanian medical students: Prevalence and associations with personality. Farmacia 2020, 68, 944–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorga, M.; Muraru, D.; Soponaru, C.; Petrariu, F. Factors influencing the level of depression among freshman nursing students. Med. Surg. J. 2017, 121, 779–786. [Google Scholar]

- Sfeatcu, R.; Balgiu, B.A.; Parlătescu, I. New psychometric evidences on the Dental Environment Stress questionnaire among Romanian students. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotaru, D.I.; Chișnoiu, R.M.; Bolboacă, S.D.; Gileru, E.A.; Chișnoiu, A.M.; Delean, A.G. Insights into self-evaluated stress, anxiety, and depression among dental students. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zugun-Eloae, C.; Iorga, M.; Gavrilescu, I.M.; Florea, S.G.; Chelaru, A. Motivation, stress and satisfaction among medical students. Med. Surg. J. 2016, 120, 688–693. [Google Scholar]

- Stoet, G. PsyToolkit: A software package for programming psychological experiments using Linux. Behav. Res. Methods 2010, 42, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, C.H. At last, my research article on procrastination. J. Res. Pers. 1986, 20, 474–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlitz, J.-Y.; Schupp, J. Zur Erhebung der Big-Five-basierten Persönlichkeitsmerkmale im SOEP: Dokumentation der Instrumentenentwicklung BFI-S auf Basis des SOEP-Pretests. DIW Res. Notes 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows [Computer Software], Version 27.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2020.

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, D.; Brooks, P.; Woolf, A.; Blyth, F.; March, L.; Bain, C.; Baker, P.; Smith, E.; Buchbinder, R. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: Modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 65, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan) [Internet]; 2020. Available online: https://Revman.cochrane.org (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Oancea, R.; Timar, B.; Papava, I.; Cristina, B.A.; Ilie, A.C.; Dehelean, L. Influence of depression and self-esteem on oral health-related quality of life in students. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L.; Ismaiel, A.; Faucambert, P.; Leucuta, D.C.; Popa, S.F.; Fadgyas, S.M.; Dumitrascu, D.L. Mental Disorders, Social Media Addiction, and Academic Performance in Romanian Undergraduate Nursing Students. JCM 2024, 13, 4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.; Keshavan, M. The neurobiology of depression: An integrated view. Asian J. Psychiatry 2017, 27, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, C.; Gold, S.M.; Penninx, B.W.; Pariante, C.M.; Etkin, A.; Fava, M.; Mohr, D.C.; Schatzberg, A.F. Major Depressive Disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016, 2, 16065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D.M.; Adams, M.J.; Shirali, M.; Clarke, T.-K.; Marioni, R.E.; Davies, G.; Coleman, J.R.I.; Alloza, C.; Shen, X.; Barbu, M.C.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study of Depression Phenotypes in UK Biobank Identifies Variants in Excitatory Synaptic Pathways. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Gomez-Carrillo, A.; Veissière, S. Culture and Depression in Global Mental Health: An Ecosocial Approach to the Phenomenology of Psychiatric Disorders. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 183, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorant, V.; Deliège, D.; Eaton, W.; Robert, A.; Philippot, P.; Ansseau, M. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 157, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrenkopf, A.M.; Sectish, T.C.; Barger, L.K.; Sharek, P.J.; Lewin, D.; Chiang, V.W.; Edwards, S.; Wiedermann, B.L.; Landrigan, C.P. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 2008, 336, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, C.G.; Chendea, A.; Licu, M. Is satisfaction with online learning related to depression, anxiety, and insomnia symptoms? A cross-sectional study on medical undergraduates in Romania. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 580–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wen, W.; Zhang, H.; Ni, J.; Jiang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, M.; Ye, L.; Feng, Z.; Ge, Z.; et al. Anxiety, depression, and stress prevalence among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 2123–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Agostino, D.; Wu, Y.-T.; Daskalopoulou, C.; Hasan, M.T.; Huisman, M.; Prina, M. Global trends in the prevalence and incidence of depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 281, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, Z.I.; Koyanagi, A.; Tyrovolas, S.; Mason, C.; Haro, J.M. The association between social relationships and depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 175, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, Y.; Lam, A.I.F.; Tang, W.; Seedat, S.; Barbui, C.; Papola, D.; Panter-Brick, C.; van der Waerden, J.; Bryant, R.; et al. Understanding the protective effect of social support on depression symptomatology from a longitudinal network perspective. BMJ Ment Health 2023, 26, e300802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Mann, F.; Lloyd-Evans, B.; Ma, R.; Johnson, S. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hefner, J.; Eisenberg, D. Social support and mental health among college students. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2009, 79, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; King, K. Developmental trajectories of anxiety and depression in early adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2015, 43, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerde, J.A.; Curtis, A.; Bailey, J.A.; Smith, R.; Hemphill, S.A.; Toumbourou, J.W. Reciprocal associations between early adolescent antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms: A longitudinal study in Victoria, Australia and Washington State, United States. J. Crim. Justice 2019, 62, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinke, W.M.; Eddy, J.M.; Dishion, T.J.; Reid, J.B. Joint trajectories of symptoms of disruptive behavior problems and depressive symptoms during early adolescence and adjustment problems during emerging adulthood. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2012, 40, 1123–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendgen, M.; Vitaro, F.; Bukowski, W.M.; Dionne, G.; Tremblay, R.E.; Boivin, M. Can friends protect genetically vulnerable children from depression? Dev. Psychopathol. 2013, 25, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEP Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI): Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Widiger, T.A.; Oltmanns, J.R. Neuroticism is a fundamental domain of personality with enormous public health implications. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakulinen, C.; Elovainio, M.; Pulkki-Råback, L.; Virtanen, M.; Kivimäki, M.; Jokela, M. Personality and depressive symptoms: Individual participant meta-analysis of 10 cohort studies. Depress Anxiety 2015, 32, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ormel, J.; Jeronimus, B.F.; Kotov, R.; Riese, H.; Bos, E.H.; Hankin, B.; Rosmalen, J.G.M.; Oldehinkel, A.J. Neuroticism and common mental disorders: Meaning and utility of a complex relationship. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendler, K.S.; Kuhn, J.; Prescott, C.A. The interrelationship of neuroticism, sex, and stressful life events in the prediction of episodes of major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, M.; Jansen, P.R.; Stringer, S.; Watanabe, K.; de Leeuw, C.A.; Bryois, J.; Savage, J.E.; Hammerschlag, A.R.; Skene, N.G.; Muñoz-Manchado, A.B.; et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for neuroticism in 449,484 individuals identifies novel genetic loci and pathways. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luciano, M.; Hagenaars, S.P.; Davies, G.; Hill, W.D.; Clarke, T.-K.; Shirali, M.; Harris, S.E.; Marioni, R.E.; Liewald, D.C.; Fawns-Ritchie, C.; et al. Association analysis in over 329,000 individuals identifies 116 independent variants influencing neuroticism. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldehinkel, A.J.; Hartman, C.A.; De Winter, A.F.; Veenstra, R.; Ormel, J. Temperament profiles associated with internalizing and externalizing problems in preadolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 2004, 16, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morken, I.S.; Viddal, K.R.; von Soest, T.; Wichstrøm, L. Explaining the female preponderance in adolescent depression: A four-wave cohort study. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2023, 51, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, J.; Flack, M. The role of self-esteem, depressive symptoms, extraversion, neuroticism and FOMO in problematic social media use: Exploring user profiles. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2024, 22, 3975–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.D.; Galambos, N.L.; Krahn, H.J. Vulnerability, scar, or reciprocal risk? Temporal ordering of self-esteem and depressive symptoms over 25 years. Longitud. Life Course Stud. 2016, 7, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, R.; Gamez, W.; Schmidt, F.; Watson, D. Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 768–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, B.W.; Walton, K.E.; Bogg, T. Conscientiousness and health across the life course. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2005, 9, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogg, T.; Roberts, B.W. Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: A meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 887–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyner, C.; Rhodes, R.E.; Loprinzi, P.D. The prospective association between the five factor personality model with health behaviors and health behavior clusters. Eur. J. Psychol. 2018, 14, 880–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor-Smith, J.K.; Flachsbart, C. Relations between personality and coping: A meta-analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 93, 1080–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, A.A.; Kohoulat, N.; Amini, M.; Faghihi, S.A.A. The predictive role of personality traits on academic performance of medical students: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2020, 34, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, D.N.; Kotov, R.; Bufferd, S.J. Personality and depression: Explanatory models and review of the evidence. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 7, 269–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.M.; Sherry, S.B.; Ray, C.; Hewitt, P.L.; Flett, G.L. Is perfectionism a vulnerability factor for depressive symptoms, a complication of depressive symptoms, or both? a meta-analytic test of 67 longitudinal studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 84, 101982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Niu, S.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. The impact of perfectionism on the incidence of major depression in Chinese medical freshmen: From a 1-year longitudinal study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 17, 4053–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, C.G.; Quilty, L.C.; Peterson, J.B. Between facets and domains: 10 aspects of the Big Five. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 93, 880–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabretti, R.R.; Zanon, C. Rumination is differentially related to openness and intellect. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2024, 227, 112677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surugiu, R.; Iancu, M.A.; Lăcătus, A.M.; Dogaru, C.A.; Stepan, M.D.; Eremia, I.A.; Neculau, A.E.; Dumitra, G.G. Unveiling the Presence of Social Prescribing in Romania in the Context of Sustainable Healthcare—A Scoping Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aughterson, H.; Fancourt, D.; Chatterjee, H.; Burton, A. Social prescribing for individuals with mental health problems: An ethnographic study exploring the mechanisms of action through which community groups support psychosocial well-being. Wellcome Open Res. 2024, 9, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ecclestone, A.; Linden, B.; Rose, J.; Kullar, K. Mobilizing health promotion through canada’s student mental health network: Concurrent, mixed methods process evaluation. JMIR Form. Res. 2025, 9, e58992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plesea-Condratovici, C.; Plesea-Condratovici, A.; Dinu, C.A.; Nicolcescu, P.; Robles-Rivera, K.; Weiser, M.; Mutica, M.; Burlea, L.S.; Ciubara, A. The Cognitive and Behavioural Impact of Social Media and Gaming on Academic Performance in Medical and Nursing Students. BRAIN Broad Res. Artif. Intell. Neurosci. 2025, 16, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Category/Statistic | N | % | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 495 | 25.14 (9.67) * | (24.29–25.99) |

| Median (Range) | 20.00 (18–54) | |||

| Gender | Male | 110 | 22.2 | (24.29–25.99) |

| Female | 385 | 77.8 | (73.7–81.4) | |

| Year of Study | 1 | 213 | 42.9 | (38.5–47.4) |

| 2 | 113 | 22.8 | (19.0–27.1) | |

| 3 | 170 | 34.3 | (30.0–38.8) | |

| Faculty | 1 (Medicine) | 364 | 73.4 | (69.2–77.2) |

| 2 (Nursing) | 119 | 24.0 | (20.0–28.4) | |

| 3–6 (Other Health Related) | 13 | 2.6 | (1.4–4.7) | |

| Residence | Urban | 402 | 82.5 | (78.8–85.7) |

| Rural | 12 | 2.5 | (1.3–4.5) | |

| Suburban | 73 | 15.0 | (12.0–18.5) | |

| Parental Education | Mean (SD) | 314 | 2.97 (1.21) | (2.84–3.10) |

| Median (Range) | 3.00 (1–6) | |||

| Has Siblings | No | 162 | 32.7 | (28.6–37.0) |

| Yes | 334 | 67.3 | (63.0–71.4) | |

| Has Partner | No | 179 | 36.1 | (31.9–40.5) |

| Yes | 317 | 63.9 | (59.5–68.1) | |

| Has Hobby | Yes | 211 | 67.0 | (61.6–72.0) |

| No | 104 | 33.0 | (28.0–38.4) | |

| Social Support | 0 (None) | 41 | 8.5 | (6.2–11.5) |

| 1 (One source) | 191 | 39.4 | (34.8–44.1) | |

| 2 (Multiple sources) | 253 | 52.2 | (47.4–57.0) |

| Depression Category | Score Range | Count (N) | Percentage (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal | 0–4 | 129 | 28.7 | (24.6–33.1) |

| Mild | 5–9 | 168 | 37.3 | (32.8–41.9) |

| Moderate | 10–14 | 88 | 19.6 | (16.1–23.6) |

| Moderately Severe | 15–19 | 42 | 9.3 | (6.8–12.5) |

| Severe | 20–27 | 23 | 5.1 | (3.4–7.6) |

| Total (Valid Scores) | 450 | 100.00 |

| Predictor | Coef. (β) | Std. Err. | t | p-Value | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 9.814 | 3.068 | 3.199 | 0.001 | |

| Procrastination Score | 0.064 | 0.025 | 2.219 | 0.027 | 1.387 |

| Neuroticism | 1.49 | 0.233 | 6.194 | <0.001 | 1.110 |

| Conscientiousness | −1.17 | 0.351 | −3.22 | <0.001 | 1.561 |

| Extroversion | −0.41 | 0.271 | −1.457 | 0.146 | 1.116 |

| Social Support | −0.805 | 0.496 | −1.633 | 0.103 | 1.051 |

| Has Partner | 0.152 | 0.657 | 0.23 | 0.818 | 1.119 |

| Parental Educ. Mean | −0.279 | 0.258 | −1.08 | 0.280 | 1.123 |

| Age | −0.04 | 0.037 | −1.047 | 0.296 | 1.391 |

| Predictor | Coef. (B) | Std. Err. | z | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procrastination Score | 0.039 | 0.017 | 2.14 | 0.003 | 1.04 (1.00–1.07) | 1.387 |

| Neuroticism | 0.477 | 0.095 | 4.95 | <0.001 | 1.87 (1.55–2.27) | 1.110 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.173 | 0.176 | 0.27 | 0.790 | 1.05 (0.74–1.48) | 1.561 |

| Extroversion | −0.220 | 0.099 | −1.99 | 0.027 | 0.77 (0.60–0.99) | 1.116 |

| Social Support | −0.264 | 0.245 | −1.08 | 0.280 | 0.77 (0.48–1.24) | 1.051 |

| Has Partner (1 = Yes) | −0.200 | 0.310 | −0.64 | 0.520 | 0.82 (0.45–1.50) | 1.119 |

| Parental Educ. Mean | −0.193 | 0.125 | −1.55 | 0.122 | 0.83 (0.65–1.05) | 1.123 |

| Age | −0.043 | 0.043 | −2.72 | 0.006 | 0.94 (0.90–0.99) | 1.391 |

| Author/Year | County/City | Sample Size | Specialty of Students | Female % | Age (Mean) | Depression N (%) | Instrument Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iorga M. et al., (2017) [18] | Iași | 89 | Nursing | 91.0 | 25.52 | 16 (18.4%) | BDI |

| Vlad R. et al., (2020) [17] | Bucharest | 315 | Medical | 83.0 | 22.86 | 136 (41.8%) | BDI |

| Oancea R. et al., (2020) [31] | Timișoara | 67 | NA | 58.2 | 25.00 | 43 (64.2%) | PHQ-9 |

| Rotaru D. et al., (2024) [20] | Cluj-Napoca Oradea | 894 | Dentistry | 78.4 | 22.00 | 127 (14.2%) | DASS-21 |

| Mihăilescu A. et al., (2011) [16] | Bucharest | 91 | Medical | 82.6 | 19.50 | 15 (16.48%) | ZSDS |

| David L. et al., (2024) [32] | Cluj-Napoca | 90 | Nursing | 91.1 | 21.00 | 34 (37.79%) | BDI |

| Instrument | N Studies | Pooled Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BDI | 3 | 32.82 (20.38–48.25) | 88.2 |

| PHQ-9 | 1 | 63.97 (51.88–74.51) | 0 |

| DASS-21 | 1 | 14.25 (12.10–16.69) | 0 |

| ZSDS | 1 | 16.85 (10.48–25.97) | 0 |

| Analysis Type | N Studies | Pooled Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Only Peer-Reviewed Studies | 2 | 50.80 (26.63–74.61) | 90.17 |

| Only Studies with ‘Strong’ Quality | 2 | 26.20 (7.40–61.18) | 99.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duica, C.L.; Negoita, S.I.; Pleșea-Condratovici, A.; Moroianu, L.-A.; Ignat, M.D.; Nicolcescu, P.; Ciubara, A.; Robles-Rivera, K.; Mititelu-Tartau, L.; Pleșea-Condratovici, C. Depression in Romanian Medical Students—A Study, Systematic Review, and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5853. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165853

Duica CL, Negoita SI, Pleșea-Condratovici A, Moroianu L-A, Ignat MD, Nicolcescu P, Ciubara A, Robles-Rivera K, Mititelu-Tartau L, Pleșea-Condratovici C. Depression in Romanian Medical Students—A Study, Systematic Review, and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(16):5853. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165853

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuica, Corina Lavinia, Silvius Ioan Negoita, Alina Pleșea-Condratovici, Lavinia-Alexandra Moroianu, Mariana Daniela Ignat, Pantelie Nicolcescu, Anamaria Ciubara, Karina Robles-Rivera, Liliana Mititelu-Tartau, and Catalin Pleșea-Condratovici. 2025. "Depression in Romanian Medical Students—A Study, Systematic Review, and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 16: 5853. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165853

APA StyleDuica, C. L., Negoita, S. I., Pleșea-Condratovici, A., Moroianu, L.-A., Ignat, M. D., Nicolcescu, P., Ciubara, A., Robles-Rivera, K., Mititelu-Tartau, L., & Pleșea-Condratovici, C. (2025). Depression in Romanian Medical Students—A Study, Systematic Review, and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(16), 5853. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14165853