The Effect of Phoniatric and Logopedic Rehabilitation on the Voice of Patients with Puberphonia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phoniatric and Logopedic Rehabilitation Program

- phoniatric and logopedic examination before voice rehabilitation,

- voice rehabilitation,

- phoniatric and logopedic examination after voice rehabilitation.

2.2. Voice Therapy Protocol

3. Results

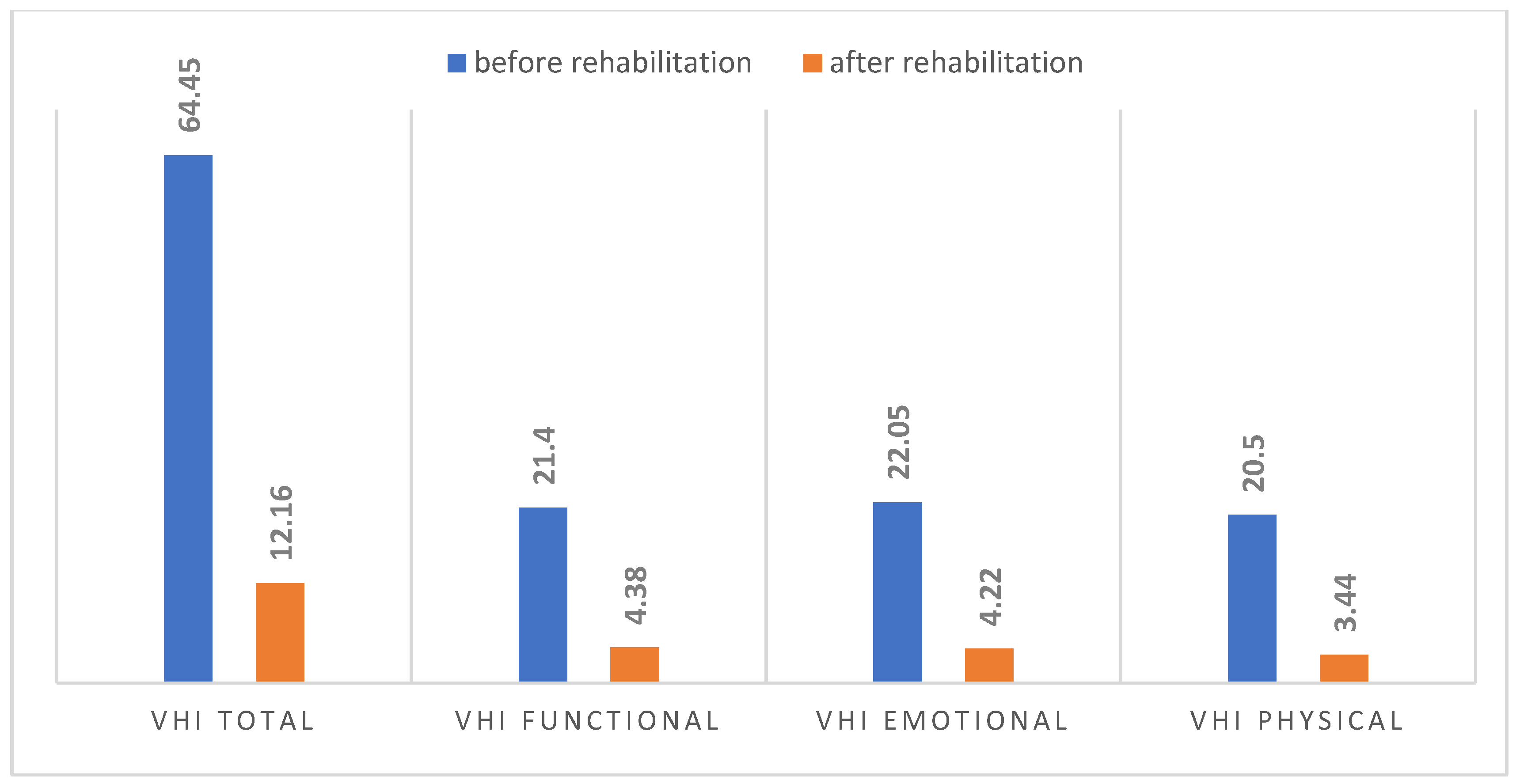

3.1. Subjective Assessment of Voice Impairment on the VHI Scale

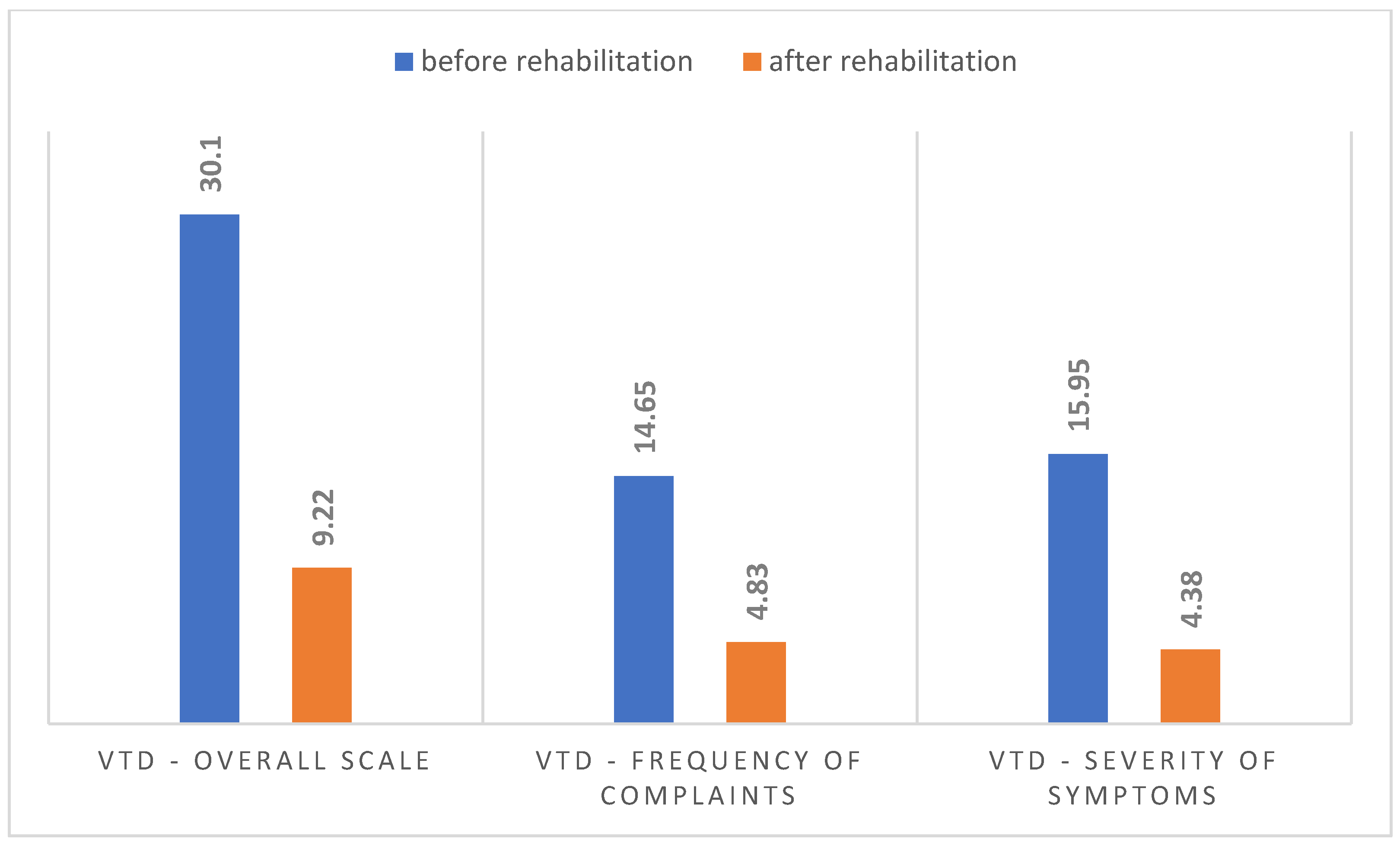

3.2. Assessment of Vocal Tract Discomfort on the VTD Scale

3.3. Assessment of Voice-Related Quality of Life on the V-RQOL Scale

3.4. Acoustic Analysis of Subjects’ Voices

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PMVI | Post-mutationalvoiceinstability |

| MF | Mutationalfalsetto |

| PFV | Persistent fistulous voice |

| VTD | Vocal tract discomfort |

| VHI | Voice Handicap Index |

| FF | Functional falsetto |

| V-RQOL | Voice-RelatedQuality of Life |

References

- Wiskirska-Woźnica, B.; Domeracka-Kołodziej, A. Dysfonie czynnościowe. Dysfonie zawodowe. In Otolaryngologia Kliniczna; Niemczyk, K., Jurkiewicz, D., Składzień, J., Stankiewicz, C., Szyfter, W., Eds.; Medipage: Warszawa, Poland, 2015; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- Wiskirska-Woźnica, B. Medyczne źródła logopedii—Foniatria i podstawy audiologii. In Biomedyczne Podstawy Logopedii; Milewski, S., Kuczkowski, J., Kaczorowska-Bray, K., Eds.; Harmonia: Gdańsk, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dubert, F.; Kozik, R.; Krawczyk, R.; Kula, A.; Marko-Worłowska, M.; Zamachowski, W. Rozmnażanie i rozwój człowieka. In Biologia na Czasie; Nowa Era: Warszawa, Poland, 2017; pp. 316–337. [Google Scholar]

- Pruszewicz, A.; Obrębowski, A. Hormonalnie uwarunkowane zaburzenia głosu. In Państwowy Zakład Wydawnictw Lekarskich; Pruszewicz, A., Ed.; Foniatria Kliniczna: Warszawa, Poland, 1992; pp. 158–172. [Google Scholar]

- Nawrocka, L.; Mackiewicz-Nartowicz, H.; Owczarzak, H.; Sinkiewicz, A.; Garstecka, A. Pomutacyjna niestabilność głosu—Opis przypadku. Logopedia 2019, 48, 339–350. [Google Scholar]

- Barmak, E.; Altan, E.; Çadallı Tatar, E.S.; Korkmaz, M.H. How persistent should we be in voice therapy in mutational falsetto patients? B-ENT 2023, 19, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Huang, X.; Chen, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Su, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Mei, X.; et al. Voice Therapy Effect on Mutational Falsetto Patients: A Vocal Aerodynamic Study. J. Voice 2017, 31, 114.e1–114.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, V.; Mishra, P. Voice therapy outcome in puberphonia. J. Laryngol. Voice 2012, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernobelskij, S. Psychogenic mutation of the voice. Comparative analysis of objective and subjective methods of diagnostics. Vestn. Otorinolaringol. 2011, 4, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dagli, M.; Sati, I.; Acar, A.; Stone, R.E. Mutational Falsetto: Intervention outcomes in 45 patients. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2008, 122, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Alwis, A.S.R.; Rupasinghe, R.J.S.; Kumarasinghe, I.; Weerasinghe, A.; Perera, R.; Jayasuriya, C. Efficacy of voice therapy in patients with puberphonia-A 15-year experience. Ceylon J. Otolaryngol. 2018, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, A.; Agrahari, A.K.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, V. Role of Voice Therapy in Patients with Mutational Falsetto. Int. J. Phonosurg. Laryngol. 2015, 5, 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, N.; Peterson, E.A.; Pierce, J.L.; Smith, M.E.; Houtz, D.R. Manual laryngeal reposturing as a primary approach for mutational falsetto. Laryngoscope 2017, 127, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, K.; Saha, S.; Pal, S.; Chatterjee, I. Effects of type 3 thyroplasty on voice quality outcomes in puberphonia. Philipp. J. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck. Surg. 2014, 29, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kızılay, A.; Fırat, Y. Treatment algorithm for patients with puberphonia. Kulak Burun Bogaz. Ihtisas. Dergisi. 2008, 18, 335–342. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich, G. Stimmstörungen (Dysphonie). In Phonoatrieund Pädaudiologie; Friedrich, G., Bigenzahn, W., Zorovka, P., Eds.; Verlag Hans Huber: Bern, Switzerland; Goöttingen, Germany; Totonto, ON, Canada; Seatle, WA, USA, 2005; pp. 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Pruszewicz, A.; Obrębowski, A. Hormonalnie Uwarunkowane Zaburzenia Głosu Mowy. In Zarys Foniatrii Klinicznej; Pruszewicz, A., Obrębowski, A., Eds.; Uniwersyte tMedyczny im. Karola Marcinkowskiego w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2019; pp. 166–173. [Google Scholar]

- Stemple, J.C.; Glaze, L.E.; Klaben, B.G. Voice Pathology: Theory and Management, Clifton Park; Delmar Cengage Learning: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, M.; Fernández-González, S.; Vázquez-de la Iglesia, F.; Urra-Barandiarán, A. Voz del Niño. Rev. Med. Univ. Navar. 2006, 50, 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowska, A.; Obrębowski, A.; Studzińska, K.; Świdziński, P. Zaburzenia głosu mutacyjnego uwarunkowane czynnikami psychicznymi Mutation voice disorders conditioned by psychic factors. Otolaryngol. Pol. 2010, 64, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattarai, B.; Shrestha, A.; Shah, S.K. Psychosocial Impact on puberphonic and effectiveness of voice therapy: A case report. J. Coll. Med. Sci.-Nepal 2010, 6, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franca, M.C.; Bass-Ringdahl, S. A clinical demonstration of the application of audiovisual biofeedback in the treatment of puberphonia. Int. J. Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 79, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Broek Emke, M.J.M.; Vokes, D.E.; Dorman, R.B. Bilateral In-Office Injection Laryngoplasty as an Adjunctive Treatment for Recalcitrant Puberphonia: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Voice 2016, 30, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wysocka, M.; Skoczylas, A.; Szkiełkowska, A.; Mularzuk, M. Standard postępowania logopedycznego w przypadku zaburzeń głosu. In Logopedia. Teoria Zaburzeń Mowy; Grabias, S., Kurkowski, M., Eds.; UMCS Lublin: Lublin, Poland, 2008; pp. 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Pruszewicz, A.; Obrębowski, A.; Wiskirska-Woźnica, B.; Wojnowski, W. W sprawie kompleksowej oceny głosu—Własna modyfikacja testu samooceny niesprawności głosu (Voice Handicap Index). Otolaryngol. Pol. 2004, 58, 547–549. [Google Scholar]

- Niebudek-Bogusz, E.; Woźnicka, E.; Śliwińska-Kowalska, M. Zastosowanie skali dyskomfortu traktu głosowego w diagnozowaniu dysfonii czynnościowej. Otolaryngol. Pol. 2010, 9, 204–209. [Google Scholar]

- Morawska, J.; Niebudek-Bogusz, E.; Zaborowski, K.; Wiktorowicz, J.; Śliwińska-Kowalska, M. Kwestionariusz V-RQOL jako narzędzie oceniające wpływ zawodowych zaburzeń głosu na jakość życia. Otolaryngol. Pol. 2015, 14, 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kothandaraman, S.; Thiagarajan, B. Mutational falsetto: A panoramic consideration. Otolaryngol. Online J. 2014, 4, 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrinowicz-Modrzejewska, A. Fizjologia i Patologia Głosu; Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne: Kraków, Poland, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Wiskirska-Woźnica, B.; Obrębowski, A.; Wojciechowska, A.; Walczak, M. Uwarunkowania miejscowe i zmysłowe przedłużonej mutacji. Otolaryngol. Pol. 2006, 60, 397–400. [Google Scholar]

- Pruszewicz, A. Metody badania narządu głosu. Postępy W Chir. 2002, 2, 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.Y.; Lim, S.E.; Choi, H.S.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, K.M.; Choi, H.S. Clinical characteristics and voice analysis of patients with mutational dysphonia: Clinical significance of diplophonia and closed quotients. J. Voice 2007, 21, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, N.; Sinha, V.; Kumar, S.S.; Katarkar, A.; Jain, A.; Sinha, V.; Dean, P.E. Efficacy of voice therapy for treatment of puberphonia: Review of 20 cases. World Artic. EarNose Throat 2012, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Niebudek Bogusz, E.; Kuzańska, A.; Woźnicka, E.; Śliwińska Kowalska, M. Ocena zaburzeń głosu u nauczycieli za pomocą wskaźnika niepełnosprawności głosowej (Voice Handicap Index—VHI). Med. Pr. 2007, 5, 393–402. [Google Scholar]

- Dehqan, A.; Yadegari, F.; Scherer, R.C.; Dabirmoghadam, P. Correlation of VHI-30 to Acoustic Measurements Across Three Common Voice Disorders. J. Voice 2017, 31, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miaśkiewicz, B.; Gos, E.; Dębińska, M.; Panasiewicz Wosik, A.; Kapustka, D.; Nikiel, K.; Włodarczyk, E.; Domeracka Kołodziej, A.; Krasnodębska, P.; Szkiełkowska, A. Polish Translation, and Validation of the Voice Handicap Index (VHI–30). Int. J. Environ. Public Health 2022, 19, 10738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Values of the VHI Questionnaire Before and After Rehabilitation | Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test, p < 0.05 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | T | Z | p | |

| VHI total | 18 | 0.00 | 3.72 | 0.00 |

| VHI functional | 18 | 0.00 | 3.72 | 0.00 |

| VHI emotional | 18 | 0.00 | 3.72 | 0.00 |

| VHI physical | 18 | 0.00 | 3.72 | 0.00 |

| VTD Questionnaire Values Before and After Rehabilitation | Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test, p < 0.05 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | T | Z | p | |

| VTD total | 18 | 0.00 | 3.72 | 0.00 |

| VTD frequency of complaints | 18 | 0.00 | 3.62 | 0.00 |

| VTD severity of symptoms | 18 | 0.00 | 3.72 | 0.00 |

| Values of the V-RQOL Questionnaire and Likert Scale Before and After Rehabilitation | Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test, p < 0.05 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | T | Z | p | |

| V-RQOL | 18 | 0.00 | 3.72 | 0.00 |

| Likert Scale | 18 | 0.00 | 3.72 | 0.00 |

| Laryngeal Tone and Formants | Before Rehabilitation n = 9 | After Rehabilitation n = 9 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Hz | Minimum Hz | Maximum Hz | Standard Deviation | Average Hz | Minimum Hz | Maximum Hz | Standard Deviation | |

| F0 | 200.49 | 151.94 | 267.74 | 42.00 | 110.97 | 90.29 | 127.64 | 12.52 |

| F1 | 521.01 | 351.45 | 621.54 | 82.86 | 507.48 | 425.72 | 594.26 | 52.51 |

| F2 | 1650.67 | 1503.92 | 1771.82 | 85.60 | 1617.53 | 1448.82 | 1723.56 | 88.61 |

| F3 | 2739.88 | 2599.16 | 2885.49 | 92.87 | 2676.23 | 2461.32 | 2795.20 | 110.43 |

| Fundamental Tone Frequencies (F0) Before and After Rehabilitation | Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test, p < 0.05 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | T | Z | p | |

| F0—median | 9 | 0.00 | 2.66 | 0.00 |

| F0—minimum | 9 | 0.00 | 2.66 | 0.00 |

| F0—maximum | 9 | 1.00 | 2.54 | 0.01 |

| Acoustic Analysis Parameters | Before Rehabilitation n = 9 | After Rehabilitation n = 9 | Results of Comparison Before and After Rehabilitation n = 9 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Minimum | Maximum | Standard Deviation | Average | Minimum | Maximum | Standard Deviation | Average | |

| Jitter | 14.75 | 0.11 | 103.68 | 21.11 | 11.50 | 0.11 | 68.88 | 16.15 | 0.84 |

| Shimmer | 8.12 | 0.50 | 48.89 | 30.94 | 5.88 | 0.41 | 30.82 | 9.61 | 0.77 |

| NHR | 2.60 | 0.36 | 10.62 | 2.12 | 1.35 | 0.27 | 4.68 | 0.89 | 0.65 |

| RAP | 13.74 | 0.57 | 91.21 | 17.96 | 10.20 | 0.52 | 48.91 | 10.72 | 0.76 |

| PPQ | 16.65 | 0.80 | 89.12 | 18.33 | 13.65 | 0.64 | 57.97 | 13.25 | 0.84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nawrocka, L.; Garstecka, A.; Sinkiewicz, A. The Effect of Phoniatric and Logopedic Rehabilitation on the Voice of Patients with Puberphonia. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5350. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155350

Nawrocka L, Garstecka A, Sinkiewicz A. The Effect of Phoniatric and Logopedic Rehabilitation on the Voice of Patients with Puberphonia. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(15):5350. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155350

Chicago/Turabian StyleNawrocka, Lidia, Agnieszka Garstecka, and Anna Sinkiewicz. 2025. "The Effect of Phoniatric and Logopedic Rehabilitation on the Voice of Patients with Puberphonia" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 15: 5350. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155350

APA StyleNawrocka, L., Garstecka, A., & Sinkiewicz, A. (2025). The Effect of Phoniatric and Logopedic Rehabilitation on the Voice of Patients with Puberphonia. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(15), 5350. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155350