Counting Limb Length Ratios in Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: A Demonstration of Safety and Feasibility Using a 25-Patient Case Series in a High-Volume Academic Center

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Outcome Measures

2.3. Surgical Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Demographics

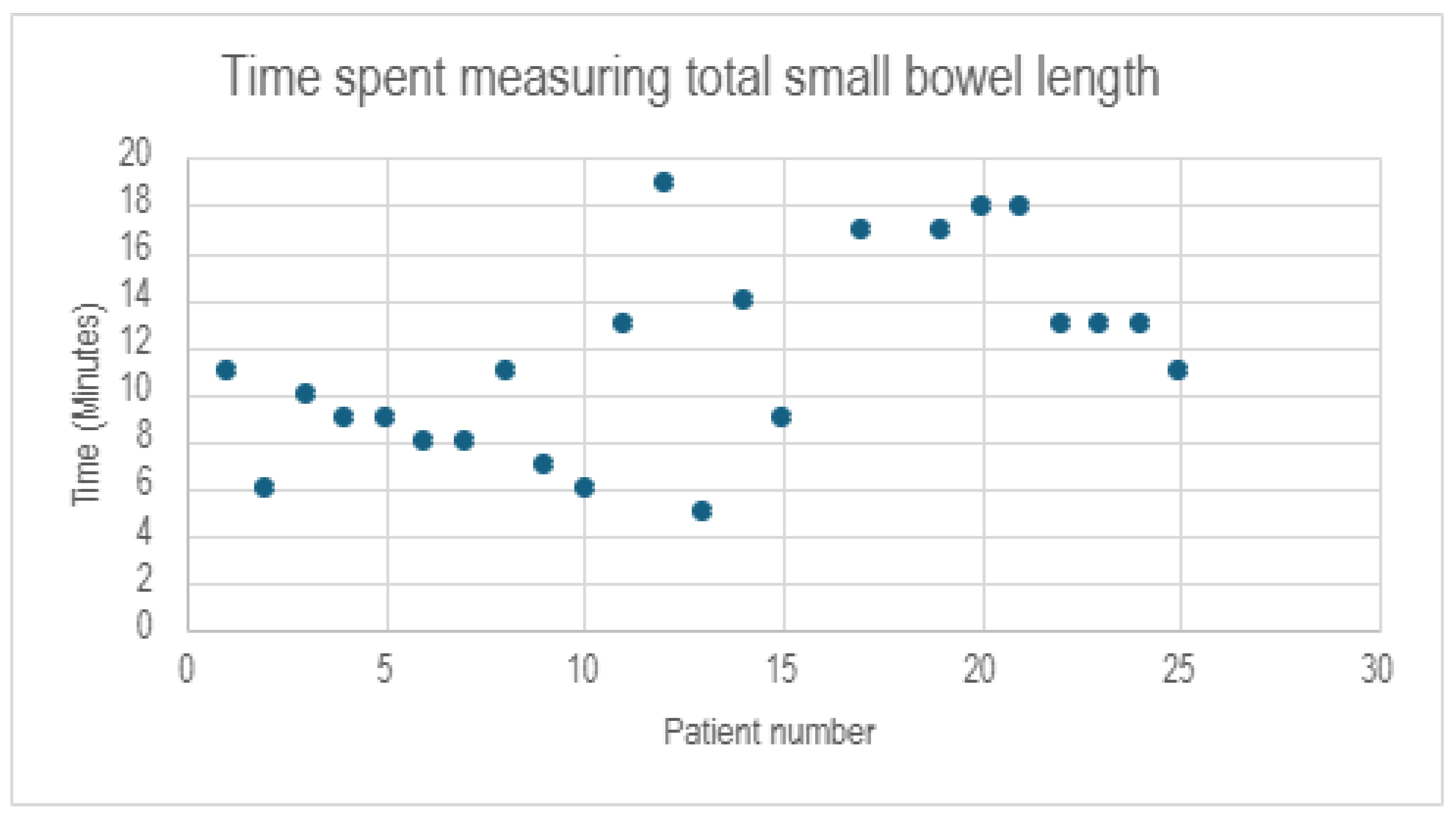

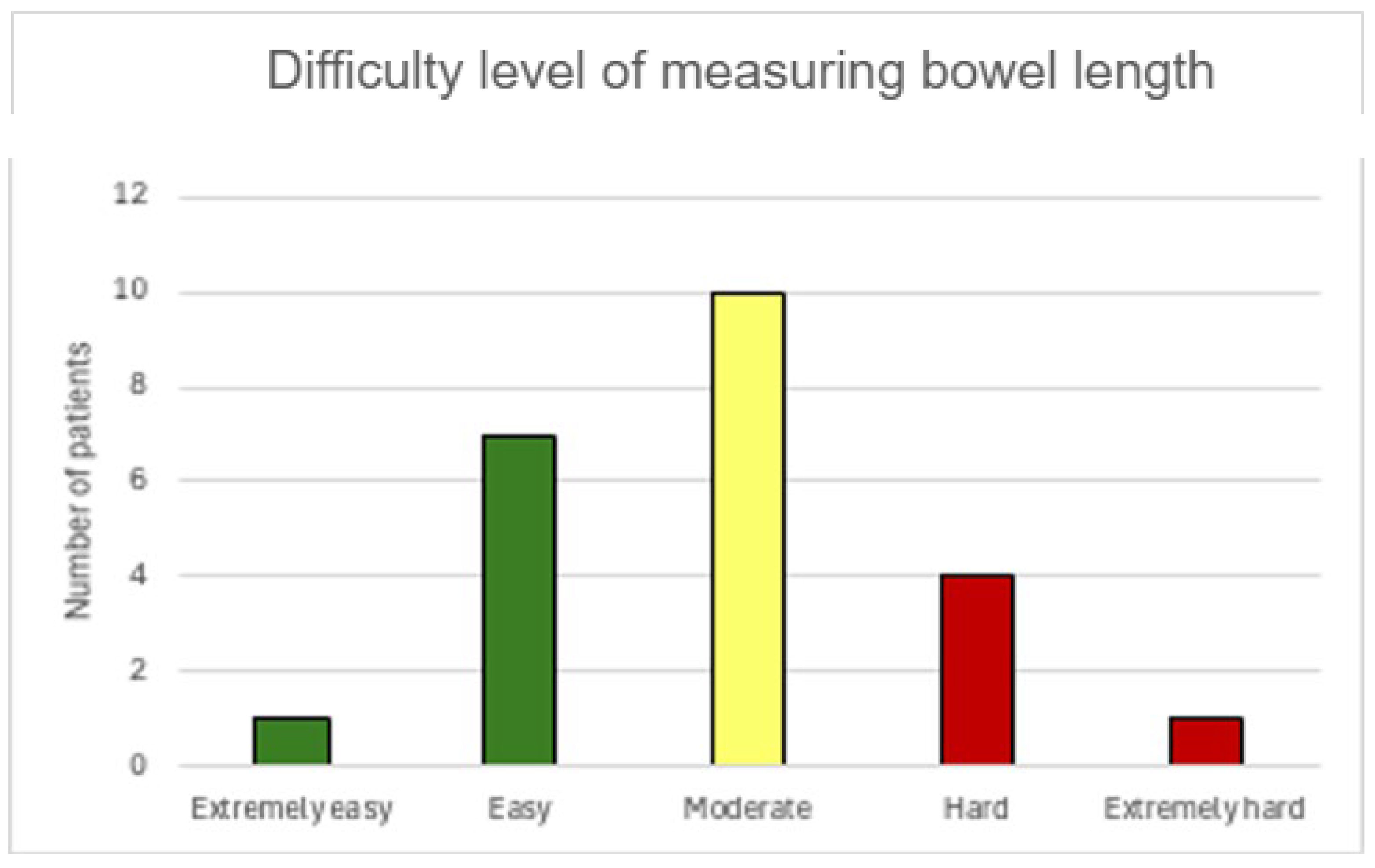

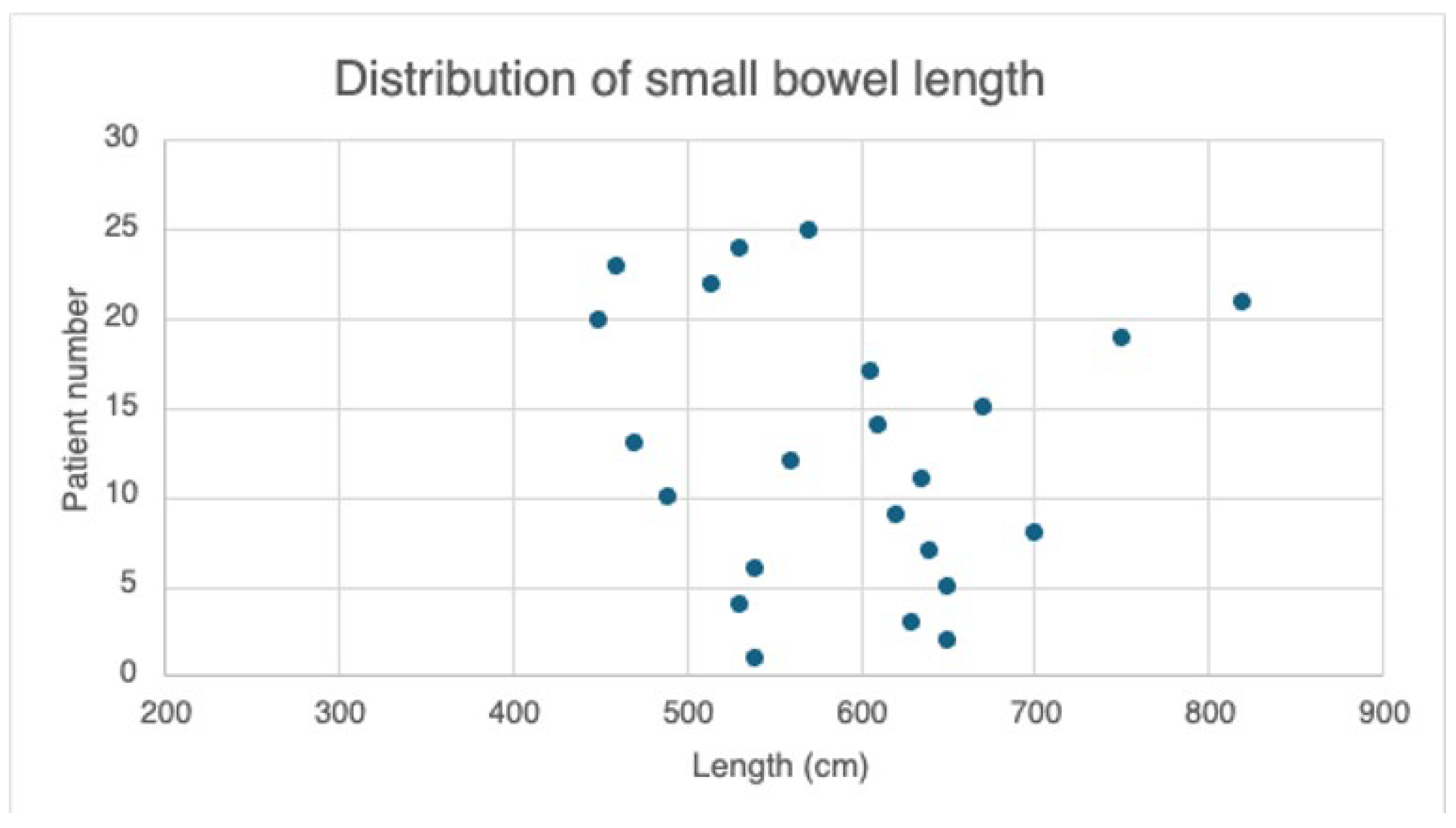

3.2. Perioperative Data

3.3. Thirty-Day Postoperative Complications

3.4. Comorbidities and Outcomes at 1 Year

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Patient ID | Iron 6 mo | Iron 1 yr | Folate 6 mo | Folate 1 yr | Vitamin B1 6 mo | Vitamin B1 1 yr | Vitamin B12 6 mo | Vitamin B12 1 yr | Vitamin D 6 mo | Vitamin D 1 yr | Calcium 6 mo | Calcium 1 yr | Zinc 6 mo | Zinc 1 yr | Copper 6 mo | Copper 1 yr | Albumin 6 mo | Albumin 1 yr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 89 | 94 | 20 | 17 | 155.4 | - | 844 | 691 | 28.8 | 27.5 | 9.6 | 9.7 | - | 76 | - | 101 | 4.3 | 4.3 |

| 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3 | 83 | 91 | - | 8.9 | 201 | 183.5 | 970 | 595 | 26.2 | 22 | 10.1 | 9.6 | - | 57 | - | 86 | 4.8 | 4.4 |

| 4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8.9 | 9.4 | - | 67 | - | 85 | 4.3 | 4.6 |

| 5 | 107 | - | 6.9 | - | 113.8 | - | 182 | - | 21.2 | - | 9.9 | - | 63 | - | 94 | - | 4.6 | - |

| 6 | 66 | 76 | >20 | >20 | - | 198.1 | 586 | 883 | 44.2 | 57.1 | 9.3 | 9 | - | 84 | - | 134 | 3.9 | 4.3 |

| 7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4.1 | 4 |

| 9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 10 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 11 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 9.6 | - | - | - | - | - | 4.6 | - |

| 12 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 9.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 13 | - | 69 | - | 18.9 | - | 226.5 | - | 1100 | - | 42.2 | - | 9.7 | - | 54 | - | 117 | - | 4.3 |

| 14 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 9.2 | - | - | - | - | - | 4.3 |

| 15 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 16 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 17 | - | - | - | 6.8 | - | - | - | 263 | - | - | - | 9.1 | - | - | - | - | - | 4.2 |

| 18 | 90 | - | 17.5 | - | 178.1 | - | 376 | - | 49.3 | - | 10.3 | 9.9 | 69 | - | 112 | - | 3.7 | 3.8 |

| 19 | 140 | - | 11.7 | - | - | - | 367 | - | 23.9 | - | 9.5 | 8.9 | - | - | - | - | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| 20 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 21 | 37 | - | - | - | 80.2 | - | 776 | - | 30.7 | - | 9.5 | - | 57 | - | 78 | - | 3.8 | - |

| 22 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 250 | - | 33.3 | - | 8.6 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 23 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 9.2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 24 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8.8 | - | - | - | - | 4 | 4.3 |

| 25 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

References

- Eagleston, J.; Nimeri, A. Optimal Small Bowel Limb Lengths of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2023, 12, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghighat, N.; Kamran, H.; Moaddeli, M.N.; Hosseini, B.; Karimi, A.; Hesameddini, I.; Amini, M.; Hosseini, S.V.; Vahidi, A.; Moeinvaziri, N. The impact of gastric pouch size, based on the number of staplers, on the short-term weight outcomes of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 84, 104914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stumpf, O.; Lange, V.; Rosenthal, A.; Lefering, R.; Paasch, C. A 30 mm sized gastrojejunostomy may lead to a lower rate of therapy failure in comparison to a 45 mm sized gastrojejunostomy following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 78, 103787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamocka, A.; Chidambaram, S.; Erridge, S.; Vithlani, G.; Miras, A.D.; Purkayastha, S. Length of biliopancreatic limb in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and its impact on post-operative outcomes in metabolic and obesity surgery-systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Obes. 2022, 46, 1983–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadiot, R.P.; Leeman, M.; Biter, L.U.; Dunkelgrun, M.; Apers, J.A.; Hof, G.V.; Feskens, P.B.; Mannaerts, G.H. Does the Length of the Common Channel as Part of the Total Alimentary Tract Matter? One Year Results from the Multicenter Dutch Common Channel Trial (DUCATI) Comparing Standard Versus Distal Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass with Similar Biliopancreatic Bowel Limb Lengths. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 4732–4740. [Google Scholar]

- Boerboom, A.; Cooiman, M.; Aarts, E.; Aufenacker, T.; Hazebroek, E.; Berends, F. An Extended Pouch in a Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass Reduces Weight Regain: 3-Year Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hort, A.; Cheng, Q.; Morosin, T.; Yoon, P.; Talbot, M. Optimal common limb length in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: Is it important for an ideal outcome?—A systematic review. ANZ J. Surg. 2023, 93, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J.T.; Deprato, A.; Verhoeff, K.; Sun, W.; Pandey, A.; Mocanu, V.; Karmali, S.; Switzer, N.J.; Nguyen, N.T. Variation of Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Techniques: A Survey of 518 Bariatric Surgeons. Obes. Surg. 2022, 32, 2357–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Yau, H.C.V.; Trivedi, A.; Yong, D.; Mahawar, K. Global Variations in Practices Concerning Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass-an Online Survey of 651 Bariatric and Metabolic Surgeons with Cumulative Experience of 158,335 Procedures. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 4339–4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, A.; Rodriguez-Quintero, J.H.; Pereira, X.; Moran-Atkin, E.; Choi, J.; Camacho, D. Gastric bypass revisional surgery: Percentage total body weight loss differences among three different techniques. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2024, 409, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süsstrunk, J.; Lazaridis, I.I.; Köstler, T.; Kraljević, M.; Delko, T.; Zingg, U. Long-Term Outcome of Proximal Versus Very-Very Long Limb Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: The Roux-Limb to Common Channel Ratio Determines the Long-Term Weight Loss. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Poliakin, L.; Sundaresan, N.; Vijayanagar, V.; Abdurakhmanov, A.; Thompson, K.J.; Mckillop, I.H.; Barbat, S.; Bauman, R.; Gersin, K.S.; et al. The role of total alimentary limb length in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: A systematic review. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bariatr. Surg. 2022, 18, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, M.; Lau, R.; Brathwaite, C.E.M.; Ragolia, L. Beyond Measure: Navigating the Complexities of Limb Length Optimization in Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery. Obes. Surg. 2024, 34, 2691–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckharter, C.; Heeren, N.; Mongelli, F.; Sykora, M.; Fenner, H.; Scheiwiller, A.; Metzger, J.; Gass, J.M. Effects of short or long biliopancreatic limb length after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery for obesity: A propensity score-matched analysis. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2022, 407, 2319–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavien, P.A.; Barkun, J.; de Oliveira, M.L.; Vauthey, J.N.; Dindo, D.; Schulick, R.D.; de Santibañes, E.; Pekolj, J.; Slankamenac, K.; Bassi, C.; et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: Five-year experience. Ann. Surg. 2009, 250, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassir, R.; Blanc, P.; Vola, M.; Tiffet, O. Common Limb Length Does Not Influence Weight Loss After Standard Laparoscopic Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass. Obes. Surg. 2016, 26, 1112–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahawar, K.K.; Kumar, P.; Parmar, C.; Graham, Y.; Carr, W.R.; Jennings, N.; Schroeder, N.; Balupuri, S.; Small, P.K. Small Bowel Limb Lengths and Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: A Systematic Review. Obes. Surg. 2016, 26, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, M.; Gadiot, R.P.; Wijnand, J.M.; Birnie, E.; Apers, J.A.; Biter, L.U.; Dunkelgrun, M. Effects of standard v. very long Roux limb Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on nutrient status: A 1-year follow-up report from the Dutch Common Channel Trial (DUCATI) Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 123, 1434–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isreb, S.; Hildreth, A.J.; Mahawar, K.; Balupuri, S.; Small, P. Laparoscopic Instruments Marking Improve Length Measurement Precision. World J. Laparosc. Surg. 2012, 2, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Voort, M.; Heijnsdijk, E.A.M.; Gouma, D.J. Bowel injury as a complication of laparoscopy. Br. J. Surg. 2004, 91, 1253–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.S.; Hess, D.W. Biliopancreatic diversion with a duodenal switch. Obes. Surg. 1998, 8, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacchino, R.M. Bowel length: Measurement, predictors, and impact on bariatric and metabolic surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bariatr. Surg. 2015, 11, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, L.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhao, W.; Ma, L.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Z.; et al. Correlation of T2DM and Anthropometric Measures with Total Small Bowel Length and Its Effects on Diabetes Remission After Bariatric Surgery. Obes. Surg. 2024, 34, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abellan, I.; Luján, J.; Frutos, M.D.; Abrisqueta, J.; Hernández, Q.; López, V.; Parrilla, P. The influence of the percentage of the common limb in weight loss and nutritional alterations after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bariatr. Surg. 2014, 10, 829–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slagter, N.; van Wilsum, M.; de Heide, L.J.; Jutte, E.H.; Kaijser, M.A.; Damen, S.L.; van Beek, A.P.; Emous, M. Laparoscopic Small Bowel Length Measurement in Bariatric Surgery Using a Hand-Over-Hand Technique with Marked Graspers: An Ex Vivo Experiment. Obes. Surg. 2022, 32, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Käkelä, P.; Rantanen, T.; Virtanen, K.A. The Importance of Intestinal Length in Triglyceride Metabolism and in Predicting the Outcomes of Comorbidities in Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass—A Narrative Review. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 3291–3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalki, O.M.; Soong, T.C.; Lee, W.J.; Chen, J.C.; Wu, C.C.; Lee, Y.C. Variation in Small Bowel Length and Its Influence on the Outcomes of Sleeve Gastrectomy. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Count (N) or Mean (±SD) |

|---|---|

| Age at time of surgery (years) | 45.0 ± 10.3 |

| Female | 23 (92.0%) |

| Race | |

| White | 13 (52.0) |

| Unknown/not reported | 6 (24.0) |

| Black | 3 (12.0) |

| Other | 3 (12.0) |

| Mean preoperative BMI (kg/m2) ± SD | 47.6 ± 8.0 |

| Hypertension | 11 (44.0) |

| Taking ≥1 antihypertensives | 11 (44.0) |

| Diabetes | |

| Non-diabetic or diet-controlled | 16 (64.0) |

| Type I diabetes mellitus | 0 (0.0) |

| Type II diabetes mellitus | 9 (36.0) |

| On short- or long-acting insulin | 7 (28.0) |

| Taking non-insulin medication | 7 (28.0) |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 17 (68.0) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 8 (32.0) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 10 (40.0) |

| Medications Used Preop | Decrease in Medications Postop n (%) | Cessation of Medications Postop n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HTN | 11 | 10 (91) | 6 (55) |

| Type 2 DM | 9 | 7 (78) | 5 (56) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elamin, D.; Wills, M.V.; Aulestia, J.; Mocanu, V.; Strong, A.; Dang, J.; Feng, X.; Kroh, M.; Corcelles, R.; Navarrete, S. Counting Limb Length Ratios in Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: A Demonstration of Safety and Feasibility Using a 25-Patient Case Series in a High-Volume Academic Center. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5262. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155262

Elamin D, Wills MV, Aulestia J, Mocanu V, Strong A, Dang J, Feng X, Kroh M, Corcelles R, Navarrete S. Counting Limb Length Ratios in Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: A Demonstration of Safety and Feasibility Using a 25-Patient Case Series in a High-Volume Academic Center. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(15):5262. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155262

Chicago/Turabian StyleElamin, Doua, Mélissa V. Wills, Juan Aulestia, Valentin Mocanu, Andrew Strong, Jerry Dang, Xiaoxi Feng, Matthew Kroh, Ricard Corcelles, and Salvador Navarrete. 2025. "Counting Limb Length Ratios in Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: A Demonstration of Safety and Feasibility Using a 25-Patient Case Series in a High-Volume Academic Center" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 15: 5262. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155262

APA StyleElamin, D., Wills, M. V., Aulestia, J., Mocanu, V., Strong, A., Dang, J., Feng, X., Kroh, M., Corcelles, R., & Navarrete, S. (2025). Counting Limb Length Ratios in Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: A Demonstration of Safety and Feasibility Using a 25-Patient Case Series in a High-Volume Academic Center. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(15), 5262. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155262