Fentanyl Research: Key to Fighting the Opioid Crisis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results

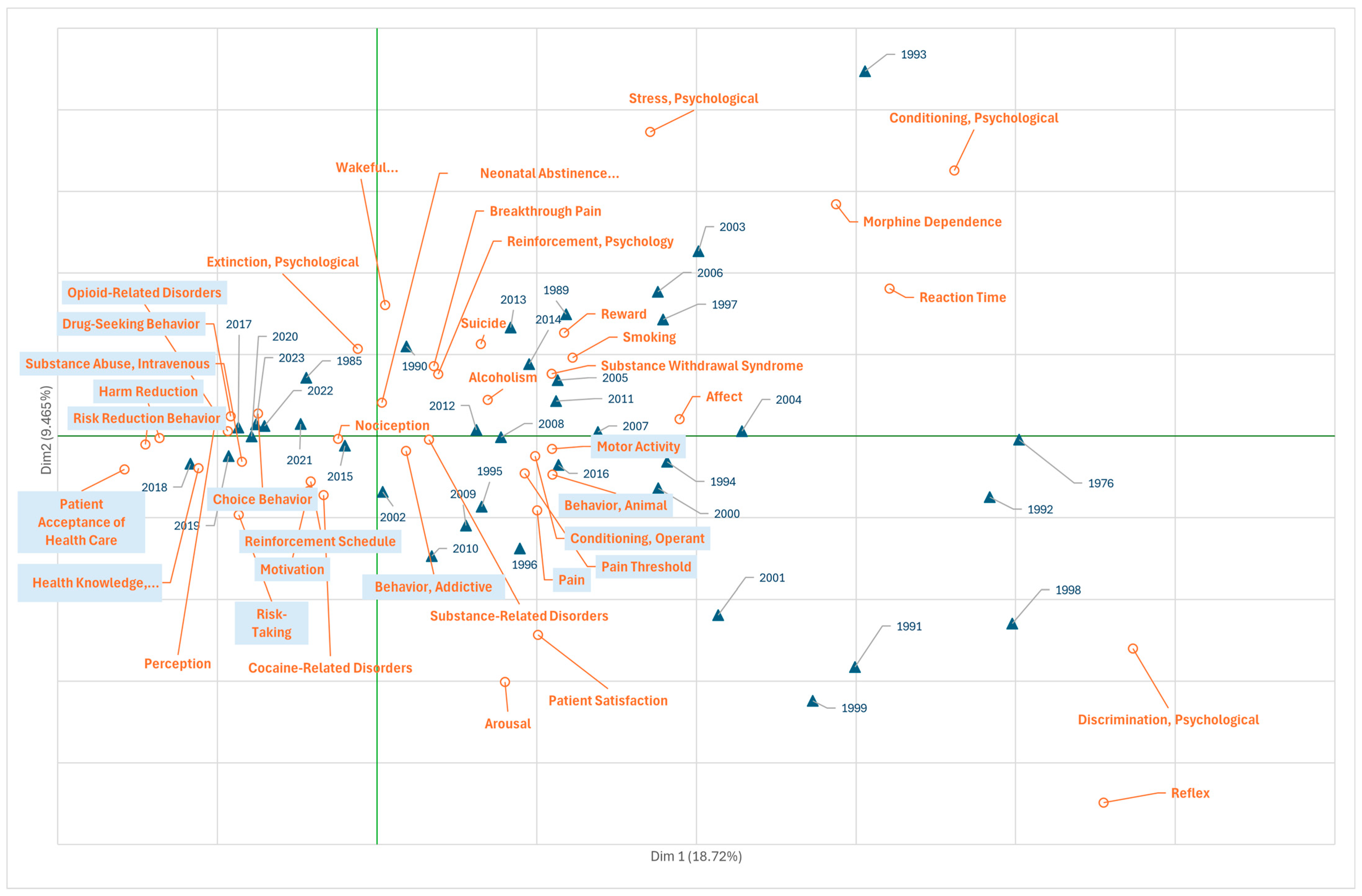

3.1. Research on Fentanyl in the Field of Psychiatry and Psychology

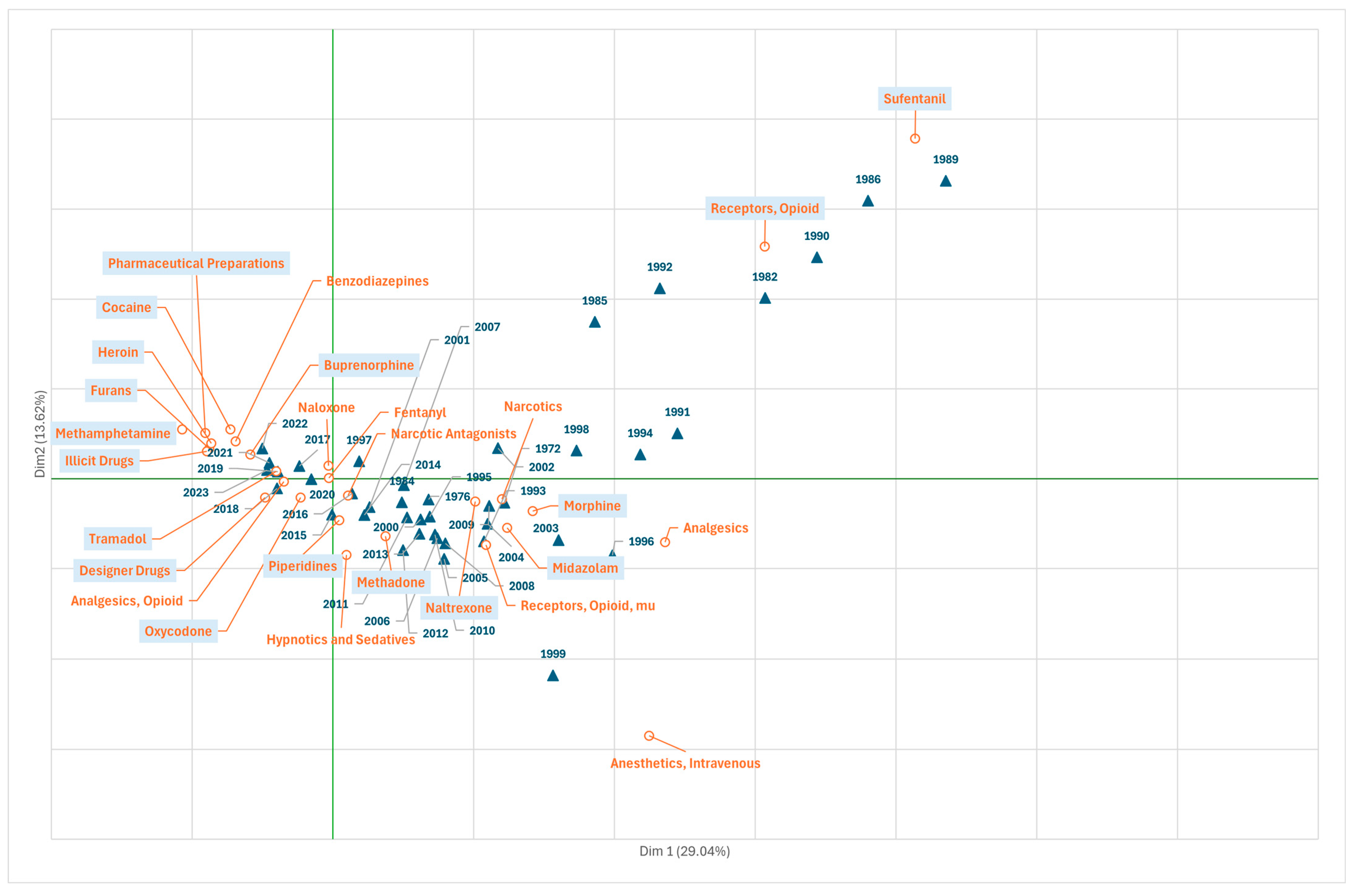

3.2. Research on Fentanyl in the Field of Chemicals and Drugs

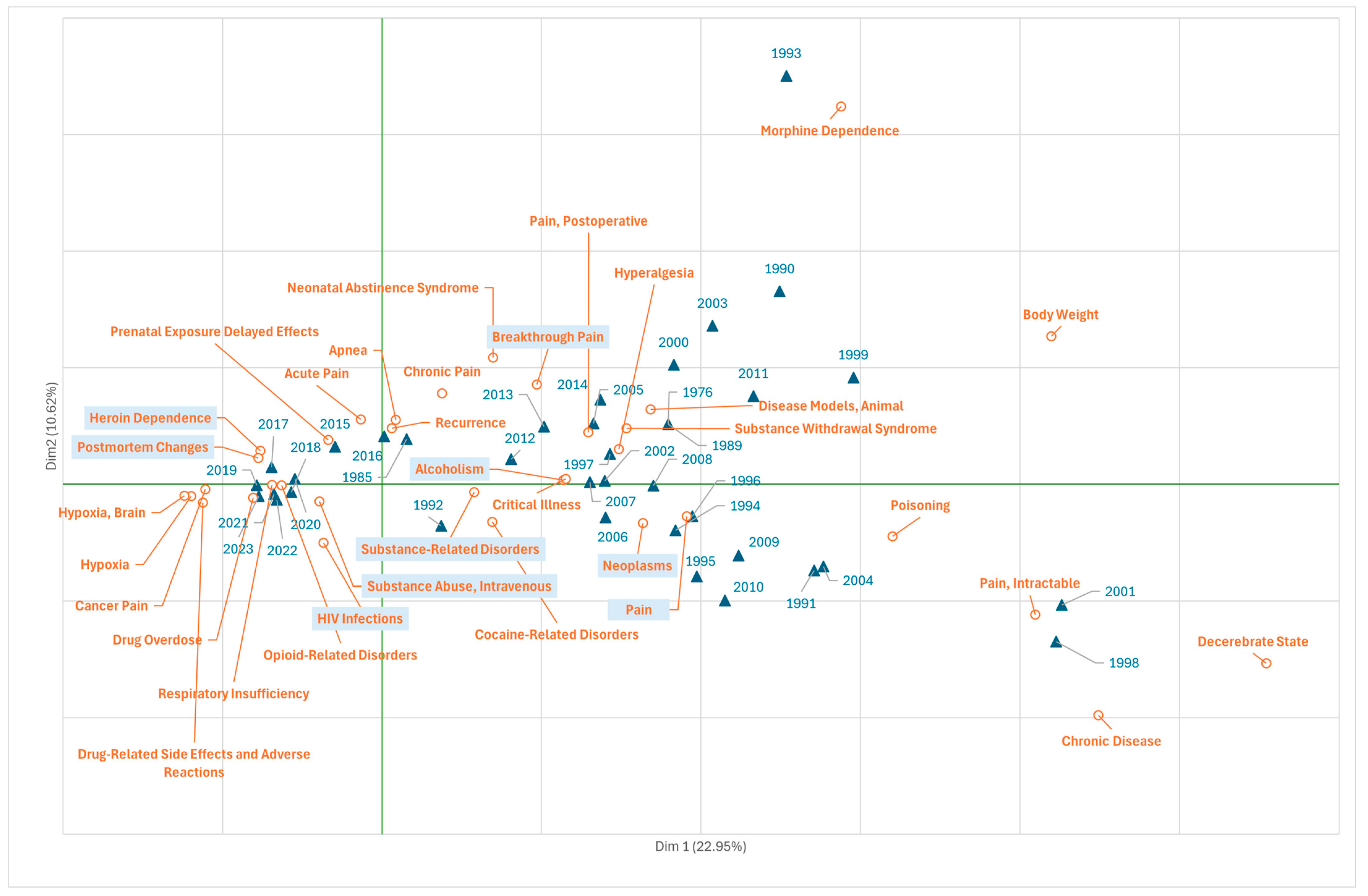

3.3. Research on Fentanyl in the Field of Health Care

3.4. Research on Fentanyl in the Field of Diseases

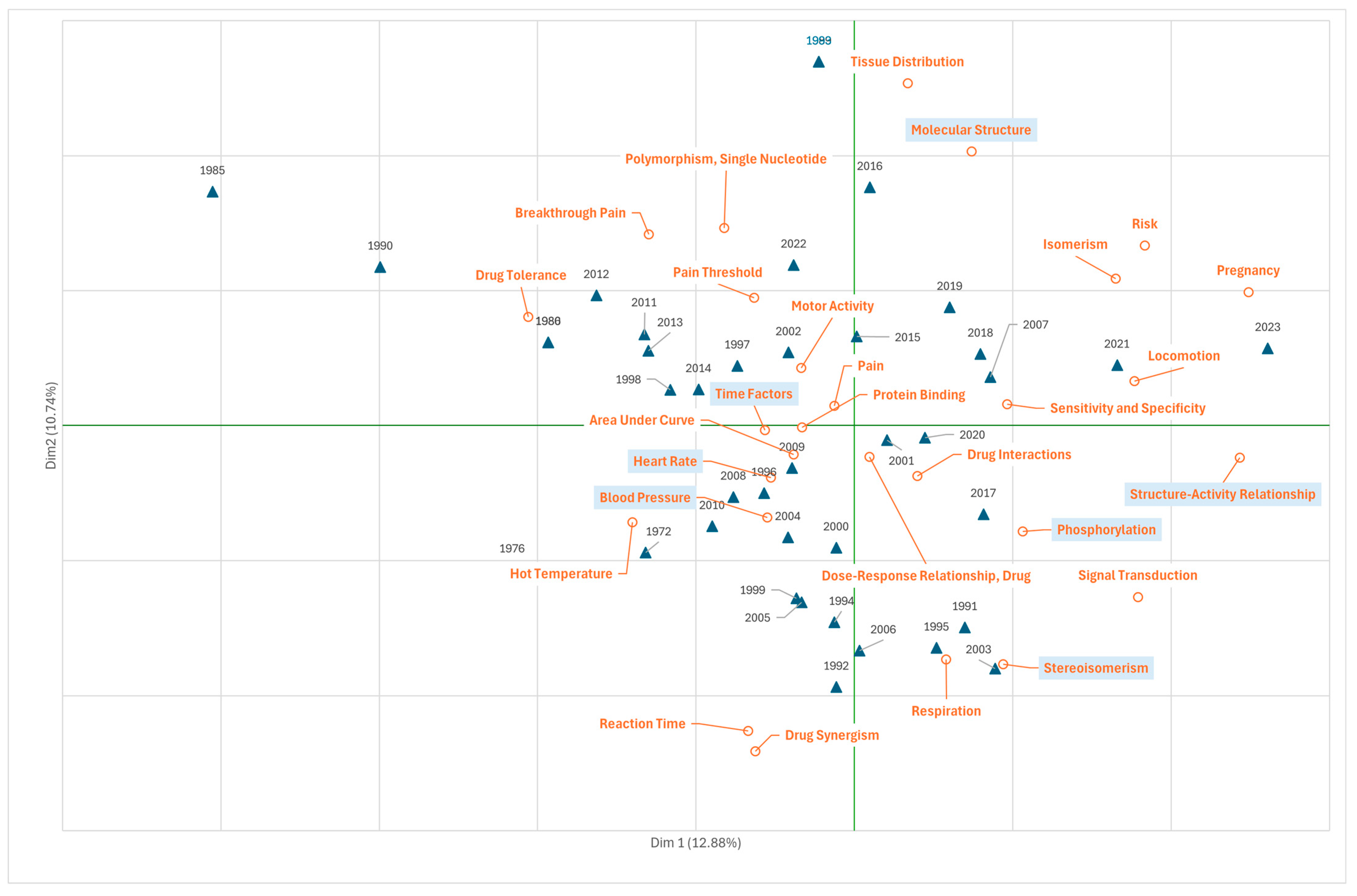

3.5. Research on Fentanyl in the Field of Phenomena and Processes

4. Discussion

4.1. First Wave: Prescription Opioid Overdose Deaths

4.2. Second Wave: Expansion of Heroin Use and Increase in Overdoses

4.3. Third Wave: Mass Use of Fentanyl and Fentanyl Analogues

4.4. Wave 4: Massive Use of Fentanyl with Stimulants

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Makary, M.A.; Overton, H.N.; Wang, P. Overprescribing Is Major Contributor to Opioid Crisis. BMJ 2017, 359, j4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Drug Overdose Deaths: Facts and Figures. Available online: https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Gardner, E.A.; McGrath, S.A.; Dowling, D.; Bai, D. The Opioid Crisis: Prevalence and Markets of Opioids. Forensic Sci. Rev. 2022, 34, 43–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schieber, L.Z.; Guy, G.P.; Seth, P.; Losby, J.L. Variation in Adult Outpatient Opioid Prescription Dispensing by Age and Sex—United States, 2008–2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloschichak, A.; Hargraves, J. Opioid Prescriptions Declined 32% for the Commercially Insured over 10 Years (2008 to 2017). Available online: https://healthcostinstitute.org/hcci-originals-dropdown/all-hcci-reports/opioid-10yr-trends (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Gisev, N.; Pearson, S.-A.; Larance, B.; Larney, S.; Blanch, B.; Degenhardt, L. A Population-Based Study of Transdermal Fentanyl Initiation in Australian Clinical Practice. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 75, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mossey, J.M. Defining Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Pain Management. Clin. Orthop. 2011, 469, 1859–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowell, D.; Ragan, K.R.; Jones, C.M.; Baldwin, G.T.; Chou, R. CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain—United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm. Rep. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. Recomm. Rep. 2022, 71, 1–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pletcher, M.J.; Kertesz, S.G.; Kohn, M.A.; Gonzales, R. Trends in Opioid Prescribing by Race/Ethnicity for Patients Seeking Care in US Emergency Departments. JAMA 2008, 299, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlhamer, J.M.; Connor, E.M.; Bose, J.; Lucas, J.L.; Zelaya, C.E. Prescription Opioid Use Among Adults with Chronic Pain: United States, 2019. Natl. Health Stat. Rep. 2021, 162, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Manchikanti, L.; Singh, V.M.; Staats, P.S.; Trescot, A.M.; Prunskis, J.; Knezevic, N.N.; Soin, A.; Kaye, A.D.; Atluri, S.; Boswell, M.V.; et al. Fourth Wave of Opioid (Illicit Drug) Overdose Deaths and Diminishing Access to Prescription Opioids and Interventional Techniques: Cause and Effect. Pain. Physician 2022, 25, 97–124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Friedman, J.; Montero, F.; Bourgois, P.; Wahbi, R.; Dye, D.; Goodman-Meza, D.; Shover, C. Xylazine Spreads across the US: A Growing Component of the Increasingly Synthetic and Polysubstance Overdose Crisis. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2022, 233, 109380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estadt, A.T.; White, B.N.; Ricks, J.M.; Lancaster, K.E.; Hepler, S.; Miller, W.C.; Kline, D. The Impact of Fentanyl on State-and County-Level Psychostimulant and Cocaine Overdose Death Rates by Race in Ohio from 2010 to 2020: A Time Series and Spatiotemporal Analysis. Harm. Reduct. J. 2024, 21, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, D.; Bunting, A.M.; Hepler, S.A.; Rivera-Aguirre, A.; Krawczyk, N.; Cerda, M. State-Level History of Overdose Deaths Involving Stimulants in the United States, 1999–2020. Am. J. Public. Health 2023, 113, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoorob, M. Fentanyl Shock: The Changing Geography of Overdose in the United States. Int. J. Drug Policy 2019, 70, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauer, J.; Stewart, K. Geographic Information Science and the United States Opioid Overdose Crisis: A Scoping Review of Methods, Scales, and Application Areas. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 317, 115525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattson, C.L.; Tanz, L.J.; Quinn, K.; Kariisa, M.; Patel, P.; Davis, N.L. Trends and Geographic Patterns in Drug and Synthetic Opioid Overdose Deaths—United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciccarone, D. The Rise of Illicit Fentanyls, Stimulants and the Fourth Wave of the Opioid Overdose Crisis. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adinolfi, I. Parliamentary Question|Europe’s Escalating Fentanyl Crisis|E-003085/2023|European Parliament. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-9-2023-003085_EN.html (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Moncrieff, T.; Moncrieff, J. A Comparison of Opioid Prescription Trends in England and the United States from 2008 to 2020. Int. J. Risk Saf. Med. 2023, 34, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalkman, G.A.; Kramers, C.; van den Brink, W.; Schellekens, A.F.A. The North American Opioid Crisis: A European Perspective. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2022, 400, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosetti, C.; Santucci, C.; Radrezza, S.; Erthal, J.; Berterame, S.; Corli, O. Trends in the Consumption of Opioids for the Treatment of Severe Pain in Europe, 1990–2016. Eur. J. Pain. Lond. Engl. 2019, 23, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, F.; Ye, J.; Wang, J.; Xia, Z. A Bibliometric Analysis of Publications on Oxycodone from 1998 to 2017. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 9096201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbar, H.F.; Siddiq, K.; Nusrat, S. Citation Classics and Trends in the Field of Opioids: A Bibliometric Analysis. Cureus 2019, 11, e5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sixto-Costoya, A.; García-Zorita, C.; Valderrama-Zurián, J.C.; Sanz-Casado, E.; Serrano-López, A.E. Evolution of Marijuana Research at the Biopsychosocial Level: A General View. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2025, 23, 603–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderrama-Zurián, J.C.; García-Zorita, C.; Marugán-Lázaro, S.; Sanz-Casado, E. Comparison of MeSH Terms and KeyWords Plus Terms for More Accurate Classification in Medical Research Fields. A Case Study in Cannabis Research. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://joaquimllisterri.cat/phonetics/fon_R/R.html (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenacre, M. Correspondence Analysis in Practice, 2nd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-429-14614-5. [Google Scholar]

- Manchikanti, L.; Helm, S.; Fellows, B.; Janata, J.W.; Pampati, V.; Grider, J.S.; Boswell, M.V. Opioid Epidemic in the United States. Pain. Physician 2012, 15, ES9–ES38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiyatkin, E.A. Respiratory Depression and Brain Hypoxia Induced by Opioid Drugs: Morphine, Oxycodone, Heroin, and Fentanyl. Neuropharmacology 2019, 151, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kibaly, C.; Alderete, J.A.; Liu, S.H.; Nasef, H.S.; Law, P.-Y.; Evans, C.J.; Cahill, C.M. Oxycodone in the Opioid Epidemic: High “Liking”, “Wanting”, and Abuse Liability. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 41, 899–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busse, J.W.; Craigie, S.; Juurlink, D.N.; Buckley, D.N.; Wang, L.; Couban, R.J.; Agoritsas, T.; Akl, E.A.; Carrasco-Labra, A.; Cooper, L.; et al. Guideline for Opioid Therapy and Chronic Noncancer Pain. J. Assoc. Medicale Can. 2017, 189, E659–E666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2016, 65, 1–49. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobski, K.; Bantel, C.; Hoffmann, F. Abuse, Dependence and Withdrawal Associated with Fentanyl and the Role of Its (Designated) Route of Administration: An Analysis of Spontaneous Reports from Europe. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 79, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tournebize, J.; Gibaja, V.; Frauger, E.; Authier, N.; Seyer, D.; Perri-Plandé, J.; Fresse, A.; Gillet, P.; Javot, L.; Kahn, J.-P.; et al. French trends in the misuse of Fentanyl: From 2010 to 2015. Therapie 2020, 75, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercadante, S.; Prestia, G.; Adile, C.; Casuccio, A. Intranasal Fentanyl Versus Fentanyl Pectin Nasal Spray for the Management of Breakthrough Cancer Pain in Doses Proportional to Basal Opioid Regimen. J. Pain. 2014, 15, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenk, S.M.; Porter, K.S.; Paulozzi, L. Prescription Opioid Analgesic Use Among Adults: United States, 1999–2012; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Preuss, C.V.; Kalava, A.; King, K.C. Prescription of Controlled Substances: Benefits and Risks. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Muijsers, R.B.; Wagstaff, A.J. Transdermal Fentanyl: An Updated Review of Its Pharmacological Properties and Therapeutic Efficacy in Chronic Cancer Pain Control. Drugs 2001, 61, 2289–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliburton, J.R. The Pharmacokinetics of Fentanyl, Sufentanil and Alfentanil: A Comparative Review. AANA J. 1988, 56, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maguire, P.; Tsai, N.; Kamal, J.; Cometta-Morini, C.; Upton, C.; Loew, G. Pharmacological Profiles of Fentanyl Analogs at Mu, Delta and Kappa Opiate Receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992, 213, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón, E.; Pernia, A.; Román, M.D.; Pérez, A.C.; Torres, L.M. Analgesia and sedation in the subarachnoid anesthesia technique: Comparative study between remifentanil and fentanyl/midazolam. Rev. Esp. Anestesiol. Reanim. 2003, 50, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soysal, S.; Karcioglu, O.; Demircan, A.; Topacoglu, H.; Serinken, M.; Ozucelik, N.; Tirpan, K.; Gunerli, A. Comparison of Meperidine plus Midazolam and Fentanyl plus Midazolam in Procedural Sedation: A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. Adv. Ther. 2004, 21, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson-Gomez, J.; Krechel, S.; Spector, A.; Weeks, M.; Ohlrich, J.; Green Montaque, H.D.; Li, J. The Effects of Opioid Policy Changes on Transitions from Prescription Opioids to Heroin, Fentanyl and Injection Drug Use: A Qualitative Analysis. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy 2022, 17, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salani, D.; Mckay, M.; Zdanowicz, M. The Deadly Trio: Heroin, FentaNYL, and Carfentanil. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2020, 46, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambdin, B.H.; Bluthenthal, R.N.; Wenger, L.D.; Wheeler, E.; Garner, B.; Lakosky, P.; Kral, A.H. Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution Within Syringe Service Programs—United States, 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1117–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cone, K.; Lanpher, J.; Kinens, A.; Richard, P.; Couture, S.; Brackin, R.; Payne, E.; Harrington, K.; Rice, K.C.; Stevenson, G.W. Delta/Mu Opioid Receptor Interactions in Operant Conditioning Assays of Pain-Depressed Responding and Drug-Induced Rate Suppression: Assessment of Therapeutic Index in Male Sprague Dawley Rats. Psychopharmacology 2018, 235, 1609–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, Z.D.; Shi, Y.-G.; Woods, J.H. Reinforcer-Dependent Enhancement of Operant Responding in Opioid-Withdrawn Rats. Psychopharmacology 2010, 212, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozarth, M.A. Opiate Reinforcement Processes: Re-Assembling Multiple Mechanisms. Addict. Abingdon Engl. 1994, 89, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigmon, S.C.; Bisaga, A.; Nunes, E.V.; O’Connor, P.G.; Kosten, T.; Woody, G. Opioid Detoxification and Naltrexone Induction Strategies: Recommendations for Clinical Practice. Am. J. Drug Alcohol. Abuse 2012, 38, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armenian, P.; Vo, K.T.; Barr-Walker, J.; Lynch, K.L. Fentanyl, Fentanyl Analogs and Novel Synthetic Opioids: A Comprehensive Review. Neuropharmacology 2018, 134, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Drugs, Brains, and Behavior: The Science of Addiction—Preface. Available online: https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/addiction-science/drugs-brain-behavior-science-of-addiction (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- van Draanen, J.; Tsang, C.; Mitra, S.; Phuong, V.; Murakami, A.; Karamouzian, M.; Richardson, L. Mental Disorder and Opioid Overdose: A Systematic Review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 647–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downs, A.; Walter, L.; Shelton, R.; Li, L. Co-Occurring Illicit Fentanyl Use and Psychiatric Disorders in Emergency Department Patients. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, K.D.; Fiuty, P.; Page, K.; Tracy, E.C.; Nocera, M.; Miller, C.W.; Tarhuni, L.J.; Dasgupta, N. Prevalence of Fentanyl in Methamphetamine and Cocaine Samples Collected by Community-Based Drug Checking Services. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2023, 252, 110985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Yu, R.; Zhang, T.; Ren, F.; Yu, Z.; Cheng, J.; Jia, H.; Shi, W.; Zhang, Y. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel Biased Mu-Opioid Receptor Agonists. Molecules 2024, 29, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagare, P.P.; Li, M.; Zheng, Y.; Kulkarni, A.S.; Obeng, S.; Huang, B.; Ruiz, C.; Gillespie, J.C.; Mendez, R.E.; Stevens, D.L.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of NAP Isosteres: A Switch from Peripheral to Central Nervous System Acting Mu-Opioid Receptor Antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 5095–5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudd, R.A.; Seth, P.; David, F.; Scholl, L. Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths—United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016, 65, 1445–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado-Vieira, R.; Zarate, C.A. Proof of Concept Trials in Bipolar Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder: A Translational Perspective in the Search for Improved Treatments. Depress. Anxiety 2011, 28, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerra, G.; Borella, F.; Zaimovic, A.; Moi, G.; Bussandri, M.; Bubici, C.; Bertacca, S. Buprenorphine versus Methadone for Opioid Dependence: Predictor Variables for Treatment Outcome. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2004, 75, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sud, A.; Strang, M.; Buchman, D.Z.; Spithoff, S.; Upshur, R.E.G.; Webster, F.; Grundy, Q. How the Suboxone Education Programme Presented as a Solution to Risks in the Canadian Opioid Crisis: A Critical Discourse Analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e059561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union Drugs Agency. EU Drug Market: Heroin and Other Opioids—Global Context. Available online: https://www.euda.europa.eu/publications/eu-drug-markets/heroin-and-other-opioids/global-context_en (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. 2020 National Drug Threat Assessment. Available online: https://www.dea.gov/documents/2021/03/02/2020-national-drug-threat-assessment (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Fonseca, N.M.; Guimarães, G.M.N.; Pontes, J.P.J.; de Araujo Azi, L.M.T.; de Ávila Oliveira, R. Safety and Effectiveness of Adding Fentanyl or Sufentanil to Spinal Anesthesia: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Braz. J. Anesthesiol. Engl. Ed. 2023, 73, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rius, C.; Serrano-López, A.E.; Lucas-Domínguez, R.; Pandiella-Dominique, A.; García-Zorita, C.; Valderrama-Zurián, J.C. Fentanyl Research: Key to Fighting the Opioid Crisis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5187. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155187

Rius C, Serrano-López AE, Lucas-Domínguez R, Pandiella-Dominique A, García-Zorita C, Valderrama-Zurián JC. Fentanyl Research: Key to Fighting the Opioid Crisis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(15):5187. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155187

Chicago/Turabian StyleRius, Cristina, Antonio Eleazar Serrano-López, Rut Lucas-Domínguez, Andrés Pandiella-Dominique, Carlos García-Zorita, and Juan Carlos Valderrama-Zurián. 2025. "Fentanyl Research: Key to Fighting the Opioid Crisis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 15: 5187. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155187

APA StyleRius, C., Serrano-López, A. E., Lucas-Domínguez, R., Pandiella-Dominique, A., García-Zorita, C., & Valderrama-Zurián, J. C. (2025). Fentanyl Research: Key to Fighting the Opioid Crisis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(15), 5187. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14155187