Nursing Care Across the Clinical Continuum of TAVI: A Systematic Review of Multidisciplinary Roles

Abstract

1. Introduction

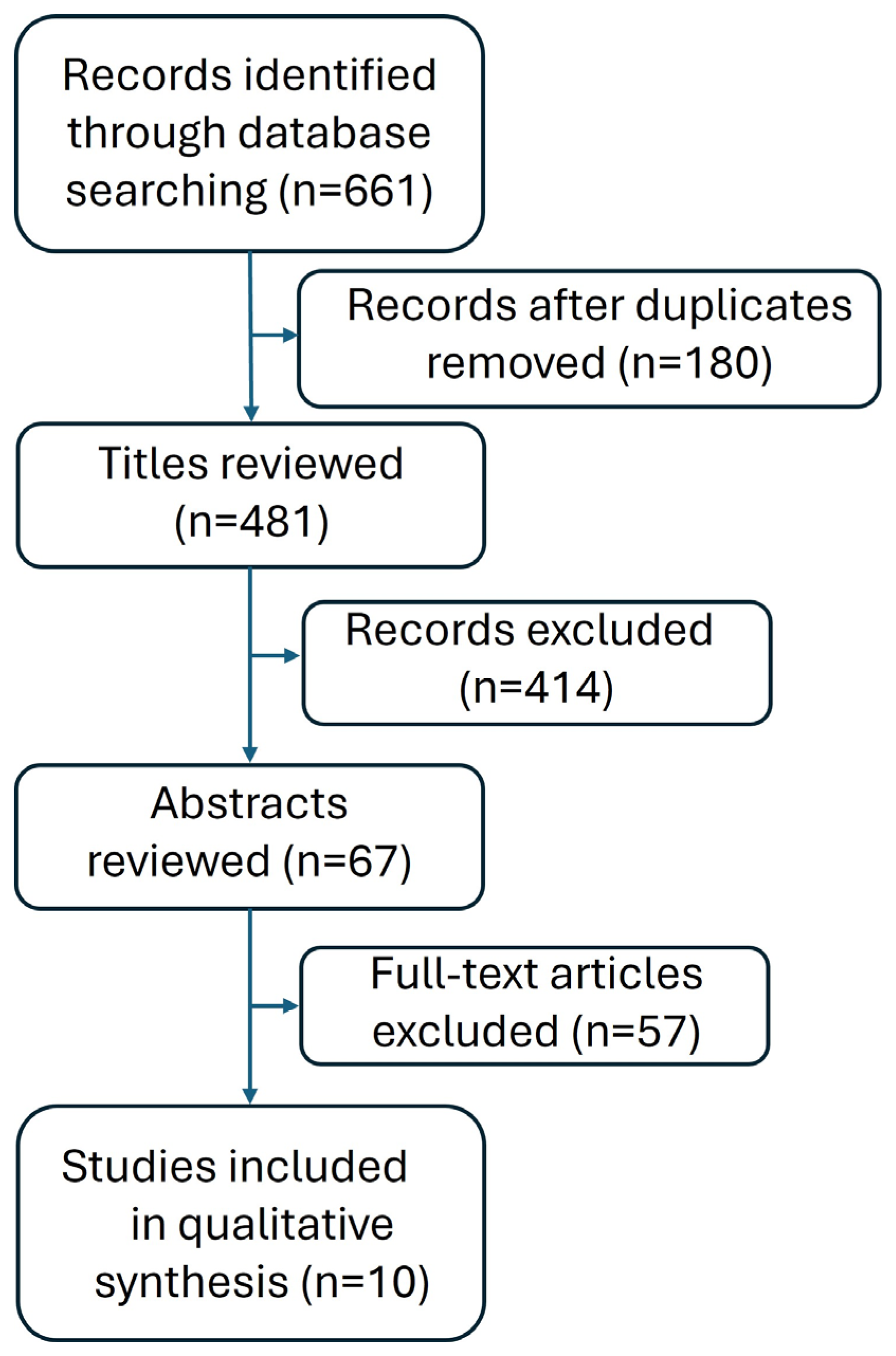

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Information on the Included Literature

2.4. Quality Assessment of the Included Studies

| No. | Author | Reference No. | Year of Publication | Number of Cases | Type of Publication | Analyzed Period | Main Findings | Nursing-Specific Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Tan et al. | [7] | 2024 | Not applicable | Review | It refers mainly to the preoperative period. | The authors emphasize the crucial role of nursing care in the context of TAVI procedures, highlighting the need for evidence-based practice in the preoperative care of patients undergoing TAVI. | Nurses act as a vital liaison between the patient and the medical team, ensuring that information and recommendations are tailored to the individual clinical and psychosocial needs of the patient. As integral members of the Heart Team, nurses conduct comprehensive preoperative assessments including physical, psychological, and social evaluations. They provide patient-centered education, reinforce adherence to perioperative care plans, and identify potential barriers to optimal recovery. Nurses monitor patient understanding, emotional status, and readiness for surgery and contribute nursing-specific findings to interdisciplinary discussions to guide personalized care planning. |

| 2. | Zou et al. | [23] | 2023 | Not applicable | Review | It refers mainly to the preoperative period. | The study provides valuable insights into the impact of cardiac rehabilitation on outcomes for patients undergoing TAVI, offering nurses evidence to enhance quality of care and improve patient results. | Nurses are integral members of the Heart Team. They perform comprehensive preoperative patient assessments that include patient education tailored to individual needs. Nurses take detailed medical, functional, and psychological history, identify nursing-specific risk factors, and use standardized risk-assessment tools. They evaluate the patients’ functional capacity, cognitive status, emotional well-being, and readiness for surgery. Nursing findings contribute directly to the interdisciplinary plan of care, highlighting patient strengths, needs, and potential barriers to recovery. |

| 3. | McCalmont et al. | [24] | 2021 | 2400 | Original research | It refers mainly to the preoperative period. | The article describes the organization of TAVI patient care within the BENCHMARK international registry, highlighting efforts to standardize care quality and resource efficiency. It discusses the multidisciplinary care structure and processes, recognizing the important role of nurses, even though they are not the primary focus. | Recommendations for nurses on preoperative care for TAVI—assessing, educating, and preparing the patient for the procedure. The results of these nursing assessments and observations are an integral part of the Heart Team’s plan of care, enabling personalized patient preparation for the procedure. |

| 4. | Kočka et al. | [25] | 2022 | 128 | Original research | It refers mainly to the perioperative period. | This article describes experiences with a nurse-led sedation (NLS) protocol during TAVI, demonstrating the feasibility and potential benefits of nurse-driven sedation management. | Nurses can safely and effectively provide sedation during TAVI and optimize early care after the procedure. |

| 5. | Tanner et al. | [26] | 2024 | Group A—59 Group B—268 Group C—736 | Original research | It refers mainly to the perioperative period and partially to the postoperative period. | The article highlights the important role of nurses responsible for data entry into the Mater TAVI database, emphasizing their contribution to data management and quality assurance in patient care. | These findings are important for nurses, helping them better monitor patients after the procedure and understand potential complications. The article can also enrich nursing education on advanced cardiac procedures. |

| 6. | Panos and George | [27] | 2014 | Not applicable | Review | It refers mainly to the postoperative period. | The work discusses in detail the nurse’s vital role in monitoring and managing patients after TAVI, emphasizing its importance within the multidisciplinary patient care team. | Nurses caring for TAVI patients must understand the potential complications, and the impact of comorbid conditions on recovery. Specialized education is essential, as TAVI requires different nursing skills compared with traditional cardiothoracic surgery. |

| 7. | Lysell and Wolf | [28] | 2021 | 14 | Original research | It refers mainly to the postoperative period. | The study highlights patients’ experiences of daily life before and after TAVI, emphasizing the importance of these insights for nurses in planning and personalizing patient care. | It relates to patients’ experiences, which are relevant to nursing in the context of mental support and rehabilitation. The nurse plays an important role in supporting the patient in regaining his or her independence and in preventing feelings of loneliness that may arise after surgery. Interventions should reinforce the patient’s sense of coherence and ability to rebuild strength, which helps him or her find his or her way in a new life situation. |

| 8. | Lauck et al. | [29] | 2020 | Not applicable | Original research—recommendations for programs | It refers mainly to the postoperative period. | The study highlights the pivotal role of the nurse leading the TAVI program as a central coordinator and communicator. | The TAVI program nurse provides seamless communication with the multidisciplinary team, is an essential central point of coordination to manage individual patient cases, and is essential to inpatient assessment, education, discharge planning, and monitoring. |

| 9. | Baumbusch et al. | [30] | 2018 | 31 | Original research | It refers mainly to the postoperative period. | The research provides valuable insights into patients’ experiences after TAVI and underscores the importance of the nurse’s role in delivering comprehensive care during the recovery period. | Nursing interventions should extend beyond the early weeks after surgery with consideration of patients’ age and disease context and caregiver involvement in the recovery process. |

| 10. | Egerod et al. | [31] | 2015 | 54 | Original research | It refers to the postoperative period. | The article details patients’ immediate post-TAVI reactions, highlighting the important aspects of nurses who monitor the patient’s condition. | The nurse’s responsibilities include monitoring pain levels, providing an environment conducive to rest, nutritional protection (for nausea and vomiting), monitoring vital signs, reporting local bleeding, supporting the patient in early mobilization, educating the patient and family, as well as working as a part of the Heart Team. |

3. Results and Data Presentation

3.1. TAVI Programs

3.2. Preoperative Visit-Care

3.3. Nurse-Led Sedation

3.4. Outcome

3.5. Nurse-Led Mobilization

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Clinical Practice

4.2. Gap in the Literature

4.3. Limitations of the Included Studies

4.4. Limitations of the Review Process

4.5. Recommendations

4.6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AS | Aortic stenosis |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| EACTS | European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery |

| SAVR | Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement |

| TAVI | Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation |

| TAVR | Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement |

References

- Di Cesare, M.; Perel, P.; Taylor, S.; Kabudula, C.; Bixby, H.; Gaziano, T.A.; McGhie, D.V.; Mwangi, J.; Pervan, B.; Narula, J.; et al. The Heart of the World. Glob. Heart 2024, 19, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aluru, J.S.; Barsouk, A.; Saginala, K.; Rawla, P.; Barsouk, A. Valvular Heart Disease Epidemiology. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Arcy, J.L.; Coffey, S.; Loudon, M.A.; Kennedy, A.; Pearson-Stuttard, J.; Birks, J.; Frangou, E.; Farmer, A.J.; Mant, D.; Wilson, J.; et al. Large-Scale Community Echocardiographic Screening Reveals a Major Burden of Undiagnosed Valvular Heart Disease in Older People: The OxVALVE Population Cohort Study. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 3515–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andell, P.; Li, X.; Martinsson, A.; Andersson, C.; Stagmo, M.; Zöller, B.; Sundquist, K.; Smith, J.G. Epidemiology of Valvular Heart Disease in a Swedish Nationwide Hospital-Based Register Study. Heart 2017, 103, 1696–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosy, A.P.; Go, A.S.; Leong, T.K.; Garcia, E.A.; Chang, A.J.; Slade, J.J.; McNulty, E.J.; Mishell, J.M.; Rassi, A.N.; Ku, I.A.; et al. Temporal Trends in the Prevalence and Severity of Aortic Stenosis within a Contemporary and Diverse Community-Based Cohort. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 384, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiecień, A.; Hrapkowicz, T.; Filipiak, K.; Przybylski, R.; Kaczmarczyk, M.; Kowalczuk, A.; Zembala, M. Surgical Treatment of Elderly Patients with Severe Aortic Stenosis in the Modern Era—Review. Pol. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 15, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Wei, G.; Ma, F.; Yan, H.; Wang, X.; Hu, Q.; Wei, W.; Yang, M.; Bai, Y. Preoperative Visit-Care for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: A Review. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heringlake, M.; Berggreen, A.E.; Vigelius-Rauch, U.; Treskatsch, S.; Ender, J.; Thiele, H. Patient Well-Being and Satisfaction after General or Local Anesthesia with Conscious Sedation: A Secondary Analysis of the SOLVE-TAVI Trial. Anesthesiology 2023, 139, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, S.; Xie, M.; Sun, X. Comparison of Safety and Effectiveness of Local or General Anesthesia after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahanian, A.; Beyersdorf, F.; Praz, F.; Milojevic, M.; Baldus, S.; Bauersachs, J.; Capodanno, D.; Conradi, L.; De Bonis, M.; De Paulis, R.; et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the Management of Valvular Heart Disease. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 561–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, C.M.; Nishimura, R.A.; Bonow, R.O.; Carabello, B.A.; Erwin, J.P.; Gentile, F.; Jneid, H.; Krieger, E.V.; Mack, M.; McLeod, C.; et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2021, 143, e72–e227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ESCARDIO. Available online: https://www.escardio.org/Sub-specialty-communities/European-Association-of-Percutaneous-Cardiovascular-Interventions-(EAPCI)# (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Clune Mulvaney, C.; Carney, M.; Kearns, T. Leveraging Momentum of 2020—Reflections from an International Conference. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbins, A.; Gannaway, A.; Parker, J.; Hyde, K.; Brown, J.; Young, S. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: Developing Nursing Practice. Br. J. Card. Nurs. 2009, 4, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Cheng, Z.; Tu, S.; Wang, X.; Xiang, C.; Zhou, W.; Chen, L. Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Hepatic Insufficiency Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2022, 22, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo Sanz, A.; Zamorano Gómez, J.L. How to Improve Patient Outcomes Following TAVI in 2024? Recent Advances. Pol. Heart J. 2024, 82, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Wei, Z.; Sun, S. Complications in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: A Comprehensive Analysis and Management Strategies. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobiano, G.; Chaboyer, W.; Tong, M.Y.T.; Eskes, A.M.; Musters, S.C.W.; Colquhoun, J.; Herbert, G.; Gillespie, B.M. Post-Operative Nursing Activities to Prevent Wound Complications in Patients Undergoing Colorectal Surgeries: A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 890–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, M.; McCanny, P.; D’Souza, M.; Forrest, P.; Burns, B.; Lowe, D.A.; Gattas, D.; Scott, S.; Bannon, P.; Granger, E.; et al. Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation for Refractory Cardiac Arrest: A Multicentre Experience. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 231, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauck, S.B.; McGladrey, J.; Lawlor, C.; Webb, J.G. Nursing Leadership of the Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Heart Team. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2016, 29, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, J.; Yuan, J.; Liu, J.; Geng, Q. Impact of Cardiac Rehabilitation on Pre- and Post-Operative Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Prognoses. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1164104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCalmont, G.; Durand, E.; Lauck, S.; Muir, D.F.; Spence, M.S.; Vasa-Nicotera, M.; Wood, D.; Saia, F.; Chatel, N.; Lüske, C.M.; et al. Setting a Benchmark for Resource Utilization and Quality of Care in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation in Europe—Rationale and Design of the International BENCHMARK Registry. Clin. Cardiol. 2021, 44, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kočka, V.; Nováčková, M.; Kratochvílová, L.; Širáková, A.; Sulženko, J.; Buděšínský, T.; Bystroń, M.; Neuberg, M.; Mašek, P.; Bednář, F.; et al. Nurse-Led Sedation for Transfemoral Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Seems Safe for a Selected Patient Population. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 2022, 24, B23–B27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, R.; Giacoppo, D.; Saber, H.; Barton, D.; Sugrue, D.; Roy, A.; Blake, G.; Spence, M.S.; Margey, R.; Casserly, I.P. Trends in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Practice and Clinical Outcomes at an Irish Tertiary Referral Centre. Open Heart 2024, 11, e002610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panos, A.M.; George, E.L. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Options For Treating Severe Aortic Stenosis in the Elderly. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. 2014, 33, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lysell, E.; Wolf, A. Patients’ Experiences of Everyday Living before and after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2021, 35, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauck, S.; Forman, J.; Borregaard, B.; Sathananthan, J.; Achtem, L.; McCalmont, G.; Muir, D.; Hawkey, M.C.; Smith, A.; Højberg Kirk, B.; et al. Facilitating Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation in the Era of COVID-19: Recommendations for Programmes. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2020, 19, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumbusch, J.; Lauck, S.B.; Achtem, L.; O’Shea, T.; Wu, S.; Banner, D. Understanding Experiences of Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: One-Year Follow-Up. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2018, 17, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerod, I.; Nielsen, S.; Lisby, K.H.; Darmer, M.R.; Pedersen, P.U. Immediate Post-Operative Responses to Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: An Observational Study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2015, 14, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.-H.; Wang, Y.-C.; Huang, H.-H.; Cheng, H.-L.; Lin, Y.-S.; Wang, M.-J.; Huang, C.-H. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: Anesthetic Experience of Retrograde Transfemoral Approach with CoreValve ReValving System. Acta Anaesthesiol. Taiwanica 2014, 52, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, S.L.; Puehler, T.; Misso, K.; Lang, S.H.; Forbes, C.; Kleijnen, J.; Danner, M.; Kuhn, C.; Haneya, A.; Seoudy, H.; et al. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation versus Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients with Severe Aortic Stenosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e054222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picou, K.; Heard, D.G.; Shah, P.B.; Arnold, S.V. Exploring Experiences Associated with Aortic Stenosis Diagnosis, Treatment and Life Impact among Middle-Aged and Older Adults. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2022, 34, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ronde-Tillmans, M.J.A.G.; Goudzwaard, J.A.; El Faquir, N.; van Mieghem, N.M.; Mattace-Raso, F.U.S.; Cummins, P.A.; Lenzen, M.J.; de Jaegere, P.P.T. TAVI Care and Cure, the Rotterdam Multidisciplinary Program for Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: Design and Rationale. Int. J. Cardiol. 2020, 302, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butala, A.D.; Sehgal, K.; Gardner, E.; Stub, D.; Palmer, S.; Noaman, S.; Guiney, L.; Htun, N.M.; Johnston, R.; Walton, A.S.; et al. Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression in Patients Who Underwent Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: The SAD-TAVI Study. Am. J. Cardiol. 2025, 235, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saia, F.; Lauck, S.; Durand, E.; Muir, D.F.; Spence, M.; Vasa-Nicotera, M.; Wood, D.; Urbano-Carrillo, C.A.; Bouchayer, D.; Iliescu, V.A.; et al. The Implementation of a Streamlined TAVI Patient Pathway across Five European Countries: BENCHMARK Registry. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, L.; Mylotte, D.; Cosyns, B.; Vanhaverbeke, M.; Zweiker, D.; Teles, R.C.; Angerås, O.; Neylon, A.; Rudolph, T.K.; Wykrzykowska, J.J.; et al. Contemporary European Practice in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: Results from the 2022 European TAVI Pathway Registry. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1227217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.Y.N.; Appleby, P.N.; Key, T.J.; Dahm, C.C.; Overvad, K.; Olsen, A.; Tjønneland, A.; Katzke, V.; Kühn, T.; Boeing, H.; et al. The Associations of Major Foods and Fibre with Risks of Ischaemic and Haemorrhagic Stroke: A Prospective Study of 418329 Participants in the EPIC Cohort across Nine European Countries. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2632–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecki, A.; Austin, P.C.; Fremes, S.E.; Tu, J.V.; Wijeysundera, H.C.; Ko, D.T. Association between Transitional Care Factors and Hospital Readmission after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: A Retrospective Observational Cohort Study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2019, 19, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, L.; Etiwy, M.; Camacho, A.; Liu, R.; Patel, N.; Tavil-Shatelyan, A.; Tanguturi, V.K.; Dal-Bianco, J.P.; Yucel, E.; Sakhuja, R.; et al. Patient- and Process-Related Contributors to the Underuse of Aortic Valve Replacement and Subsequent Mortality in Ambulatory Patients With Severe Aortic Stenosis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e025065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegermann, Z.K.; Mack, M.J.; Arnold, S.V.; Thompson, C.A.; Ryan, M.; Gunnarsson, C.; Strong, S.; Cohen, D.J.; Alexander, K.P.; Brennan, J.M. Anxiety and Depression Following Aortic Valve Replacement. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e024377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohmann, K.; Burgdorf, C.; Zeus, T.; Joner, M.; Alvarez, H.; Berning, K.L.; Schikowski, M.; Kasel, A.M.; van Mark, G.; Deutsch, C.; et al. The COORDINATE Pilot Study: Impact of a Transcatheter Aortic Valve Coordinator Program on Hospital and Patient Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, J.; Collins, P.; Flatley, M.; Hope, J.; Young, A. Older People’s Experiences in Acute Care Settings: Systematic Review and Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 102, 103469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Hu, S.; Wang, Y.; Yang, T.; Chen, L.; Zhang, D.; Ding, Y. Conventional Aortic Valve Replacement versus Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: Professional Requirements for Nurses. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 4369–4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villablanca, P.A.; Mohananey, D.; Nikolic, K.; Bangalore, S.; Slovut, D.P.; Mathew, V.; Thourani, V.H.; Rode’s-Cabau, J.; Núñez-Gil, I.J.; Shah, T.; et al. Comparison of Local versus General Anesthesia in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: A Meta-analysis. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2018, 91, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, H.; Kurz, T.; Feistritzer, H.-J.; Stachel, G.; Hartung, P.; Lurz, P.; Eitel, I.; Marquetand, C.; Nef, H.; Doerr, O.; et al. General Versus Local Anesthesia With Conscious Sedation in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Circulation 2020, 142, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İzgi, M.; Halis, A.; Şener, Y.Z.; Şahiner, L.; Kaya, E.B.; Aytemir, K.; Heves Karagöz, A. Evaluation of Anaesthetic Approaches in Transcatheter Aortic Valv Implantation Procedures. Turk. J. Anaesthesiol. Reanim. 2023, 51, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cereda, A.; Allievi, L.; Busetti, L.; Koleci, R.; De Nora, V.; Vecchia, A.; Toselli, M.; Giannini, F.; Tumminello, G.; Sangiorgi, G. Nurse-Led Distal Radial Access: Efficacy, Learning Curve, and Perspectives of an Increasingly Popular Access. Does Learning by Doing Apply to Both the Doctor and the Nurse? Minerva Cardiol. Angiol. 2023, 71, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimian, S.; Chervu, N.; Balian, J.; Mallick, S.; Yang, E.H.; Ziaeian, B.; Aksoy, O.; Benharash, P. Timing of Noncardiac Surgery Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 17, 1693–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Jones, P.M. Sedation versus General Anesthesia for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, S3588–S3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou, P.; Analitis, A.; Sbarouni, E.; Voudris, V. Prognostic Performance of Critical Care Scores in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. J. Intensive Care Soc. 2016, 17, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuno, T.; Demirel, C.; Tomii, D.; Erdoes, G.; Heg, D.; Lanz, J.; Praz, F.; Zbinden, R.; Reineke, D.; Räber, L.; et al. Risk and Timing of Noncardiac Surgery After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2220689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmaljy, H.; Tawney, A.; Young, M. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement; Statpearls: Tampa, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ina Tamburino, C.; Barbanti, M.; Tamburino, C. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: How to Decrease Post-Operative Complications. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 2020, 22, E148–E152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.; Lanctôt, K.L.; Fremes, S.E.; Wijeysundera, H.C.; Radhakrishnan, S.; Gallagher, D.; Gandell, D.; Brenkel, M.C.; Hazan, E.L.; Docteur, N.G.; et al. The Value of Screening for Cognition, Depression, and Frailty in Patients Referred for TAVI. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkar, R.R.; Thourani, V.H.; Mack, M.J.; Kodali, S.K.; Kapadia, S.; Webb, J.G.; Yoon, S.-H.; Trento, A.; Svensson, L.G.; Herrmann, H.C.; et al. Five-Year Outcomes of Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic-Valve Replacement. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauck, S.B.; Yu, M.; Bancroft, C.; Borregaard, B.; Polderman, J.; Stephenson, A.L.; Durand, E.; Akodad, M.; Meier, D.; Andrews, H.; et al. Early Mobilization after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: Observational Cohort Study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2024, 23, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafri, S.H.; Hushcha, P.; Dorbala, P.; Bousquet, G.; Lutfy, C.; Klein, J.; Mellett, L.; Sonis, L.; Polk, D.; Skali, H. Physical and Psychological Well-Being Effects of Cardiac Rehabilitation on Patients Following Mitral Valve and Aortic Valve Procedures. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2022, 42, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penati, C.; Incorvaia, C.; Mollo, V.; Lietti, F.; Gatto, G.; Stefanelli, M.; Centeleghe, P.; Talarico, G.; Mori, I.; Franzelli, C.; et al. Cardiac Rehabilitation Outcome after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2021, 91, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamulevičiūtė-Prascienė, E.; Beigienė, A.; Thompson, M.J.; Balnė, K.; Kubilius, R.; Bjarnason-Wehrens, B. The Impact of Additional Resistance and Balance Training in Exercise-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation in Older Patients after Valve Surgery or Intervention: Randomized Control Trial. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oz, A.; Tsoumas, I.; Lampropoulos, K.; Xanthos, T.; Karpettas, N.; Papadopoulos, D. Cardiac Rehabilitation After TAVI –A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2023, 48, 101531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, C.; Holmberg, M.; Jernby, E.E.; Hansen, A.S.; Bremer, A. Older Patients’ Autonomy When Cared for at Emergency Departments. Nurs. Ethics 2022, 29, 1266–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alodhialah, A.M.; Almutairi, A.A.; Almutairi, M. Ethical and Legal Challenges in Caring for Older Adults with Multimorbidities: Best Practices for Nurses. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entwistle, V.A.; Carter, S.M.; Cribb, A.; McCaffery, K. Supporting Patient Autonomy: The Importance of Clinician-Patient Relationships. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010, 25, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Yu, H.; Wang, Q. Nurses’ Experiences Concerning Older Adults with Polypharmacy: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Findings. Healthcare 2023, 11, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, G.C.; de Albuquerque, D.C.; Rocha, R.G.; Fernandes, R.T.P.; Lima, L.C.L.C.; Cabral, A.P.V. Nursing Protocol in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: Care Guideline. Esc. Anna Nery 2018, 22, e20170260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moons, P.; Luyckx, K.; Thomet, C.; Budts, W.; Enomoto, J.; Sluman, M.A.; Lu, C.-W.; Jackson, J.L.; Khairy, P.; Cook, S.C.; et al. Physical Functioning, Mental Health, and Quality of Life in Different Congenital Heart Defects: Comparative Analysis in 3538 Patients From 15 Countries. Can. J. Cardiol. 2021, 37, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Klein, U.; Weigert, A.; Schiller, W.; Bayley-Ezziddin, V.; Wirtz, D.C.; Welz, A.; Werner, N.; Grube, E.; Nickenig, G.; et al. Use of Pre- and Intensified Postprocedural Physiotherapy in Patients with Symptomatic Aortic Stenosis Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Study (the 4P-TAVR Study). J. Interv. Cardiol. 2021, 2021, 894223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gempel, S.; Cohen, M.; Milian, E.; Vidret, M.; Smith, A.; Jones, I.; Orozco, Y.; Kirk-Sanchez, N.; Cahalin, L.P. Inspiratory Muscle and Functional Performance of Patients Entering Cardiac Rehabilitation after Cardiac Valve Replacement. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2023, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dsouza, F.V.; Amaravadi, S.K.; Samuel, S.R.; Raghavan, H.; Ravishankar, N. Effectiveness of Inspiratory Muscle Training on Respiratory Muscle Strength in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgeries: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 45, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wei, J.; Liu, J.; Feng, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Li, Q.; He, S.; Chen, Y.; Peng, Y.; et al. Inspiratory Muscle Training Improves Cardiopulmonary Function in Patients after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2023, 30, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jendrzejczak, A.; Klukow, J.; Czerwik-Marcinkowska, J.; Styk, W.; Zmorzynski, S. Nursing Care Across the Clinical Continuum of TAVI: A Systematic Review of Multidisciplinary Roles. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4535. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134535

Jendrzejczak A, Klukow J, Czerwik-Marcinkowska J, Styk W, Zmorzynski S. Nursing Care Across the Clinical Continuum of TAVI: A Systematic Review of Multidisciplinary Roles. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(13):4535. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134535

Chicago/Turabian StyleJendrzejczak, Anna, Jadwiga Klukow, Joanna Czerwik-Marcinkowska, Wojciech Styk, and Szymon Zmorzynski. 2025. "Nursing Care Across the Clinical Continuum of TAVI: A Systematic Review of Multidisciplinary Roles" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 13: 4535. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134535

APA StyleJendrzejczak, A., Klukow, J., Czerwik-Marcinkowska, J., Styk, W., & Zmorzynski, S. (2025). Nursing Care Across the Clinical Continuum of TAVI: A Systematic Review of Multidisciplinary Roles. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(13), 4535. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134535