Secondary Submuscular Gluteal Implant Replacement: The Safe Hybrid Bridge Technique

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting, and Patient Population

2.2. Technical Description of the Procedure: The Safe Hybrid Bridge Technique

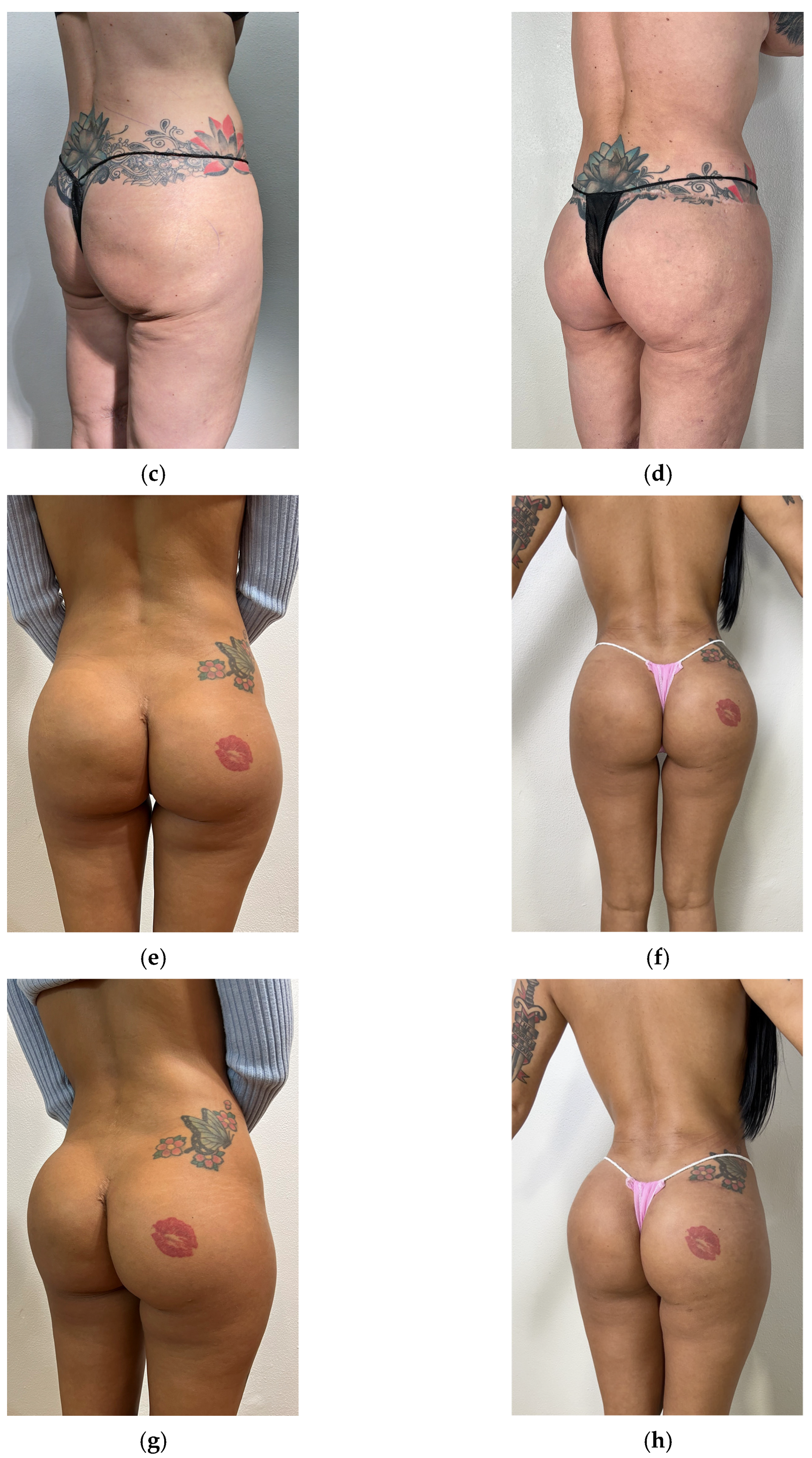

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bartels, R.J.; O’Malley, J.E.; Douglas, W.M.; Wilson, R.G. An Unusual Use of the Cronin Breast Prosthesis. Case Report. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1969, 44, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocke, W.M.; Ricketson, G. Gluteal Augmentation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1973, 52, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunstad, J.P.; Repta, R. Purse-String Gluteoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2009, 123, 123e–125e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oranges, C.M.; Tremp, M.; Di Summa, P.G.; Haug, M.; Kalbermatten, D.F.; Harder, Y.; Schaefer, D.J. Gluteal Augmentation Techniques: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2017, 37, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perén, P.A.; Gómez, J.B.; Guerrerosantos, J.; Salazar, C.A. Gluteus Augmentation with Fat Grafting. Aesthet. Plast. Surg. 2000, 24, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T. Augmentation of the Buttocks by Micro Fat Grafting. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2001, 21, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, J. Large-Volume Lipoinjection for Gluteal Augmentation. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2002, 22, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meyere, B.; Mir-Mir, S.; Peñas, J.; Camenisch, C.C.; Hedén, P. Stabilized Hyaluronic Acid Gel for Volume Restoration and Contouring of the Buttocks: 24-Month Efficacy and Safety. Aesthet. Plast. Surg. 2014, 38, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacur, R.; Sampaio Menezes, H.; Maria Bordin Da Silva Chacur, N.; Dias Alves, D.; Cadore Mafaldo, R.; Dias Gomes, L.; Dos Santos Barreto, G. Gluteal Augmentation with Polymethyl Methacrylate: A 10-Year Cohort Study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.—Glob. Open 2019, 7, e2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durairaj, K.K.; Devgan, L.; Lee, A.; Khachatourian, N.; Nguyen, V.; Issa, T.; Baker, O. Poly-l-Lactic Acid for Gluteal Augmentation Found to Be Safe and Effective in Retrospective Clinical Review of 60 Patients. Dermatol. Surg. 2020, 46, S46–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.J.; Dubin, D.P.; Khorasani, H. Poly-l-Lactic Acid for Minimally Invasive Gluteal Augmentation. Dermatol. Surg. 2020, 46, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozer, S.O.; Agullo, F.J.; Wolf, C. Autoprosthesis Buttock Augmentation During Lower Body Lift. Aesthet. Plast. Surg. 2005, 29, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raposo-Amaral, C.E.; Cetrulo, C.L.; Guidi, M.D.C.; Ferreira, D.M.; Raposo-Amaral, C.M. Bilateral Lumbar Hip Dermal Fat Rotation Flaps: A Novel Technique for Autologous Augmentation Gluteoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006, 117, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, R.; Gonzalez, R. Intramuscular Gluteal Augmentation: The XYZ Method. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2018, 45, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank Statistics. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2015, 35, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Oranges, C.M.; Haug, M.; Schaefer, D.J. Body Contouring. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 138, 944e–945e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, R. Intramuscular Gluteal Implants: 15 Years’ Experience. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2003, 23, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergara, R.; Marcos, M. Intramuscular Gluteal Implants. Aesthet. Plast. Surg. 1996, 20, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Peña-Salcedo, J.A.; Soto-Miranda, M.A.; Vaquera-Guevara, M.O.; Lopez-Salguero, J.F.; Lavareda-Santana, M.A.; Ledezma-Rodriguez, J.C. Gluteal Lift with Subfascial Implants. Aesthet. Plast. Surg. 2013, 37, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delapena, J. Subfascial Technique for Gluteal Augmentation. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2004, 24, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, F.; Aboudib, J.H.; Marques, R.G. Intramuscular Technique for Gluteal Augmentation: Determination and Quantification of Muscle Atrophy and Implant Position by Computed Tomographic Scan. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 131, 253e–259e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, F.; Aboudib, J.H.; Neto, J.I.S.; Cossich, V.R.A.; Rodrigues, N.C.P.; de Oliveira, K.F.; Marques, R.G. Volumetric and Functional Evaluation of the Gluteus Maximus Muscle after Augmentation Gluteoplasty Using Silicone Implants. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 135, 533e–541e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltez, G.; Aboudib, J.H.; Serra, F. Long-Term Aesthetic and Functional Evaluation of Intramuscular Augmentation Gluteoplasty with Implants. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2023, 151, 40e–46e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Society of Plastic Surgeons. 2015 Plastic Surgery Statistics; American Society of Plastic Surgeons: Arlington Heights, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS). ISAPS International Survey on Aesthetic/Cosmetic Procedures Performed in 2014; International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery: West Lebanon, NH, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sinno, S.; Chang, J.B.; Brownstone, N.D.; Saadeh, P.B.; Wall, S. Determining the Safety and Efficacy of Gluteal Augmentation: A Systematic Review of Outcomes and Complications. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 137, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, F.; Aboudib, J.H. Gluteal Implant Displacement: Diagnosis and Treatment. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2014, 134, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, R. Buttocks Reshaping. Posterior Contour Surgery: A Step-by-Step Approach Including Thigh and Calf Implant, 1st ed.; Indexa: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2006; ISBN 978-85-60138-00-5. [Google Scholar]

- Jaimovich, C.A.; Rocha Almeida, M.W.; De Souza Aguiar, L.F.; Da Silva, M.L.A.; Pitanguy, I. Internal Suture Technique for Improving Projection and Stability in Secondary Gluteoplasty. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2010, 30, 411–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Petit, F.; Colli, M.; Badiali, V.; Ebaa, S.; Salval, A. Buttocks Volume Augmentation with Submuscular Implants: 100 Cases Series. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 149, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, L.A. Angiogenesis and Wound Repair: When Enough Is Enough. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2016, 100, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, J.E. Submuscular Gluteal Augmentation: 17 Years of Experience With Gel and Elastomer Silicone Implants. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2006, 33, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, T.W.; Roberts, T.L.; Nguyen, K. Complications of Buttocks Augmentation: Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2006, 33, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Guimarães, F.; De Barros, M.A.V.; Aboudib, J.H.; Da Mota, D.S.C.; Leal, D.G.; De Castro, C.C.; Nahas, F.X. Does Intramuscular Gluteal Augmentation Using Implants Affect Sensitivity in the Buttocks? J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2017, 70, 801–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, B.S.; Yarbrough, C.; Price, A.; Biswas, R. An Unfortunate Injection. BMJ Case Rep. 2016, 2016, bcr2015211127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramtahal, J.; Ramlakhan, S.; Singh, K. Sciatic Nerve Injury Following Intramuscular Injection: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2006, 38, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D. Adaptive Significance of Female Physical Attractiveness: Role of Waist-to-Hip Ratio. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 65, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnino, B.; Navajas, J.; Sigman, M. Eye Fixations Indicate Men’s Preference for Female Breasts or Buttocks. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2012, 41, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca-Guerra, R.; Lugo-Beltran, I. Beautiful Buttocks: Characteristics and Surgical Techniques. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2006, 33, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oranges, C.M.; Gohritz, A.; Kalbermatten, D.F.; Schaefer, D.J. Ethnic Gluteoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 138, 783e–784e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.L.; Weinfeld, A.B.; Bruner, T.W.; Nguyen, K. “Universal” and Ethnic Ideals of Beautiful Buttocks Are Best Obtained by Autologous Micro Fat Grafting and Liposuction. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2006, 33, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.H.; Whang, K.W. Buttock Reshaping With Intramuscular Gluteal Augmentation in an Asian Ethnic Group: A Six-Year Experience With 130 Patients. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2016, 77, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senderoff, D.M. Aesthetic Surgery of the Buttocks Using Implants: Practice-Based Recommendations. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2016, 36, 559–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, J.; Tagliapietra, J.; Grande, M. Gluteoplastia de Aumento: Implante Submuscular. Cir. Plast. Iberolatinoamericana 1984, 10, 365–369. [Google Scholar]

- Serra, F.; Aboudib, J.H.; Marques, R.G. Reducing Wound Complications in Gluteal Augmentation Surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012, 130, 706e–713e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendieta, C. Gluteoplasty. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2003, 23, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, R.; Mentz, J.; Hallman, T.G.; Castillo, C. Subfascial/Intramuscular Dual-Plane Gluteal Implantation and Supplemental Fat Grafting: A Novel Technique for Buttock Augmentation. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2023, 43, 1499–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslani, A.; Del Vecchio, D.; Bravo, M.G.; Zholtikov, V.; Palhazi, P. The Dual Plane Gluteal Augmentation. An Anatomical Demonstration of a New Pocket Design. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 151, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaftawy, A.; Ostrowski, P.; Bonczar, M.; Stolarski, M.; Gabryszuk, K.; Bonczar, T. Enhancing Buttock Contours: A Safer Approach to Gluteal Augmentation with Ultrasonic Liposuction, Submuscular Implants, and Ultrasound-Guided Fat Grafting. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaftawy, A.; Bonczar, T.; Stolarski, M.; Gabryszuk, K. Submuscular Buttock Augmentation With Silicone Implants in 80 Female Patients. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2024, 44, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmouz, S.G.; Riccio, C.A.; Patel, K.; Haran, O.; Shifrin, D. Implant-Based Gluteal Augmentation: Comparing Complications Between Single- and Double-Incision Techniques. Aesthet. Plast. Surg. 2024, 48, 3406–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Complication | Number of Patients | Percentage of Total (N = 108) |

|---|---|---|

| All * | 17 | 15.7% |

| Sciatic pain lasting >10 days | 8 | 7.4% |

| Implant flipping | 7 | 6.5% |

| Hematoma | 6 | 5.6% |

| Temporary alteration in sensitivity | 4 | 3.7% |

| Asymmetry | 4 | 3.7% |

| Delayed wound healing | 2 | 1.9% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Colli, M.; Giordano, S.; Dondè, E.; Gennai, A. Secondary Submuscular Gluteal Implant Replacement: The Safe Hybrid Bridge Technique. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4486. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134486

Colli M, Giordano S, Dondè E, Gennai A. Secondary Submuscular Gluteal Implant Replacement: The Safe Hybrid Bridge Technique. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(13):4486. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134486

Chicago/Turabian StyleColli, Mattia, Salvatore Giordano, Enrico Dondè, and Alessandro Gennai. 2025. "Secondary Submuscular Gluteal Implant Replacement: The Safe Hybrid Bridge Technique" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 13: 4486. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134486

APA StyleColli, M., Giordano, S., Dondè, E., & Gennai, A. (2025). Secondary Submuscular Gluteal Implant Replacement: The Safe Hybrid Bridge Technique. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(13), 4486. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14134486