The Use of Virtual Reality as a Non-Pharmacological Approach for Pain Reduction During the Debridement and Dressing of Hard-to-Heal Wounds

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Subject

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Respondents

3.2. Wound Characteristics

3.3. Pain Management Treatment Provided

3.4. Pain Symptoms During the Wound Debridement Procedure

3.5. Selected Variables and Pain Symptoms

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations of the Study

- Patients reporting NRS pain greater than four at the first assessment were excluded from the study due to the high risk of exacerbating pain during ongoing procedures

- Patients who were taking opioid medication were excluded due to the risk of pain escalation as well as the risk of falsification.

- During the study, 2% lidocaine gel was applied to the wound in both study groups for pain relief.

- During the study, active distraction in the form of manual patient involvement was not used. During the study, in the group of patients who used Google VR, visualization with sound was used. Patients were allowed to look around during wound treatment if this did not interfere with the wound cleansing process.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mäntyselkä, P.; Kumpusalo, E.; Ahonen, R.; Kumpusalo, A.; Kauhanen, J.; Viinamäki, H.; Halonen, P.; Takala, J. Pain as a reason to visit the doctor: A study in Finnish primary health care. Pain 2001, 89, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, S.N.; Carr, D.B.; Cohen, M.; Finnerup, N.B.; Flor, H.; Gibson, S.; Keefe, F.J.; Mogil, J.S.; Ringkamp, M.; Sluka, K.A.; et al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: Concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 2020, 161, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, K.; Murphy, C.; Gregg, E.; Moralejo, J.; LeBlanc, K.; Brandys, T. Management of Pain in People Living with Chronic Limb Threatening Ischemia: Highlights from a Rapid Umbrella Review. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2024, 51, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.P.; Tse, M.M.Y.; Qin, J. Effectiveness of Virtual Reality-Based Interventions for Managing Chronic Pain on Pain Reduction, Anxiety, Depression and Mood: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsararatee, H.H.; Langley, J.C.S.; Thorburn, M.; Burton-Gow, H.; Whitby, S.; Powell, S. Assessment of the diabetic foot in inpatients. Br. J. Nurs. 2025, 34, S12–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, K.Y.; Sibbald, R.G. Chronic wound pain: A conceptual model. Adv. Ski. Wound Care 2008, 21, 175–188; quiz 189–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanschik, D.; Bruno, R.R.; Wolff, G.; Kelm, M.; Jung, C. Virtual and augmented reality in intensive care medicine: A systematic review. Ann. Intensive Care 2023, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Huang, Q.; Lin, J.; Han, R.; Peng, C.; Huang, A. Using Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy in Pain Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Value Health 2022, 25, 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrozikiewicz-Rakowska, B.; Jawień, A.; Szewczyk, T.M.; Sopata, M.; Korzon-Burakowska, A.; Dziemidok, P.; Gorczyca-Siudak, D.; Tochman-Gawda, A.; Krasiński, Z.; Rowiński, O.; et al. Management of Patients with Diabetic Foot Syndrome—Guidelines of the Polish Wound Treatment Society 2021: Part 1. Leczenie Ran 2021, 18, 71–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.Q.; Leng, Y.F.; Ge, J.F.; Wang, D.W.; Li, C.; Chen, B.; Sun, Z.L. Effectiveness of Virtual Reality in Nursing Education: Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, W.; Li, W.; Wang, T.; Zheng, Y. Effectiveness of virtual reality in nursing education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osumi, M.; Inomata, K.; Inoue, Y.; Otake, Y.; Morioka, S.; Sumitani, M. Characteristics of phantom limb pain alleviated with virtual reality rehabilitation. Pain Med. 2018, 20, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Hu, R.; Yin, Y.; He, F. Effects of non-pharmacological interventions on pain in wound patients during dressing change: A systematic review. Nurs. Open 2024, 11, e2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, J.; Shin, J.; Chung, J.; Ji, S.-H.; Ro, S.; Kim, W. Virtual reality distraction during endoscopic urologic surgery under spinal anesthesia: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzori, B.; Lauro Grotto, R.; Giugni, A.; Calabrò, M.; Alhalabi, W.; Hoffman, H.G. Virtual reality analgesia for pediatric dental patients. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, E.D.; Dinçer, N.Ü. The Effects of Virtual Reality Glasses on Vital Signs and Anxiety in Patients Undergoing Colonoscopy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2023, 46, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyrka, K.; Rojczyk, E.; Brela, J.; Sieroń, A.; Kucharzewski, M. Virtual reality as a promising method of pain relief in patients with venous leg ulcers. Int. Wound J. 2024, 21, e70082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araujo, T.M.; da Silva, A.S.J.; Brandao, M.; Barros, L.M.; Veras, V.S. Virtual reality in pain relief during chronic wound dressing change. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2021, 55, e20200513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyer, K.; Herberger, K.; Protz, K.; Glaeske, G.; Augustin, M. Epidemiology of chronic wounds in Germany: Analysis of statutory health insurance data. Wound Repair Regen. 2016, 24, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.; Richardson, E.J. Effects of virtual walking treatment on spinal cord injury-related neuropathic pain: Pilot results and trends related to location of pain and at-level neuronal hypersensitivity. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 95, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślik, B.; Mazurek, J.; Rutkowski, S.; Kiper, P.; Turolla, A.; Szczepańska-Gieracha, J. Virtual reality in psychiatric disorders: A systematic review of reviews. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 52, 102480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malloy, K.M.; Milling, L.S. The effectiveness of virtual reality distraction for pain reduction: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buche, H.; Michel, A.; Blanc, N. Use of virtual reality in oncology: From the state of the art to an integrative model. Front. Virtual Real. 2022, 3, 894162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, S.T.; Jimenez, R.T.; Wang, E.Y.; Zuniga-Hernandez, M.; Titzler, J.; Jackson, C.; Suen, M.Y.; Yamaguchi, C.; Ko, B.; Kong, J.T.; et al. Virtual reality improves pain threshold and recall in healthy adults: A randomized, crossover study. J. Clin. Anesth. 2025, 103, 111816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gender p = 0.317 | Group | |||||

| Total | Group A—No Goggles | Group B—Goggles | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Female | 51 | 51.0% | 23 | 46.0% | 28 | 56.0% |

| Male | 49 | 49.0% | 27 | 54.0% | 22 | 44.0% |

| Total | 100 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% |

| Age p = 0.075 | Group | |||||

| Total | Group A | Group B | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Up to 64 years | 30 | 30.0% | 19 | 38.0% | 11 | 22.0% |

| 65–74 years | 45 | 45.0% | 17 | 34.0% | 28 | 56.0% |

| 75+ years | 25 | 25.0% | 14 | 28.0% | 11 | 22.0% |

| Total | 100 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% |

| Residence Location p = 0.039 | Group | |||||

| Total | Group A | Group B | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| City | 38 | 38.0% | 24 | 48.0% | 14 | 28.0% |

| Village | 62 | 62.0% | 26 | 52.0% | 36 | 72.0% |

| Total | 100 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% |

| Self-Care Capacity p = 0.838 | Group | |||||

| Total | Group A | Group B | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| I. 86–100—Self-care sufficient | 61 | 61.0% | 31 | 62.0% | 30 | 60.0% |

| II. 21–85—Self-care deficit | 39 | 39.0% | 19 | 38.0% | 20 | 40.0% |

| III. 0–20—Self-care insufficient | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Total | 100 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% |

| Wound Etiology p = 0.189 | Group | |||||

| Total | Group A | Group B | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Venous leg ulcer (VLU) | 49 | 49.0% | 21 | 42.0% | 28 | 56.0% |

| Mixed ulcer | 35 | 35.0% | 20 | 40.0% | 15 | 30.0% |

| Peripheral artery disease (PAD) | 6 | 6.0% | 5 | 10.0% | 1 | 2.0% |

| Ulcer secondary to diabetic foot disease (DFD) | 10 | 10.0% | 4 | 8.0% | 6 | 12.0% |

| Total | 100 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% |

| Wound Localization p = 0.688 | Group | |||||

| Total | Group A | Group B | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Foot | 14 | 14.0% | 8 | 16.0% | 6 | 12.0% |

| Lower leg (circumferential wound) | 6 | 6.0% | 2 | 4.0% | 4 | 8.0% |

| Lower leg medial part | 55 | 55.0% | 29 | 58.0% | 26 | 52.0% |

| Lower leg lateral part | 25 | 25.0% | 11 | 22.0% | 14 | 28.0% |

| Total | 100 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% |

| Wound Onset Time p = 0.034 | Group | |||||

| Total (months) | Group A | Group B | ||||

| Average | 7.16 | 5.92 | 8.40 | |||

| SD | 5.08 | 4.49 | 5.36 | |||

| Median | 5.0 | 4.0 | 7.0 | |||

| Min | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Max | 20.0 | 20.0 | 18.0 | |||

| Q1 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | |||

| Q3 | 12.0 | 6.0 | 12.0 | |||

| n | 100 | 50 | 50 | |||

| Types of Medication Acc. to WHO p = 0.358 | Group | |||||

| Total | Group A | Group B | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Level I | 75 | 75.0% | 38 | 76.0% | 37 | 74.0% |

| Level II | 23 | 23.0% | 12 | 24.0% | 11 | 22.0% |

| Level III | 2 | 2.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 4.0% |

| Total | 100 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% |

| Painkiller Use Patterns p = 0.656 | Group | |||||

| Total | Group A | Group B | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Regular use | 28 | 28.0% | 13 | 26.0% | 15 | 30.0% |

| As needed | 72 | 72.0% | 37 | 74.0% | 35 | 70.0% |

| Total | 100 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% |

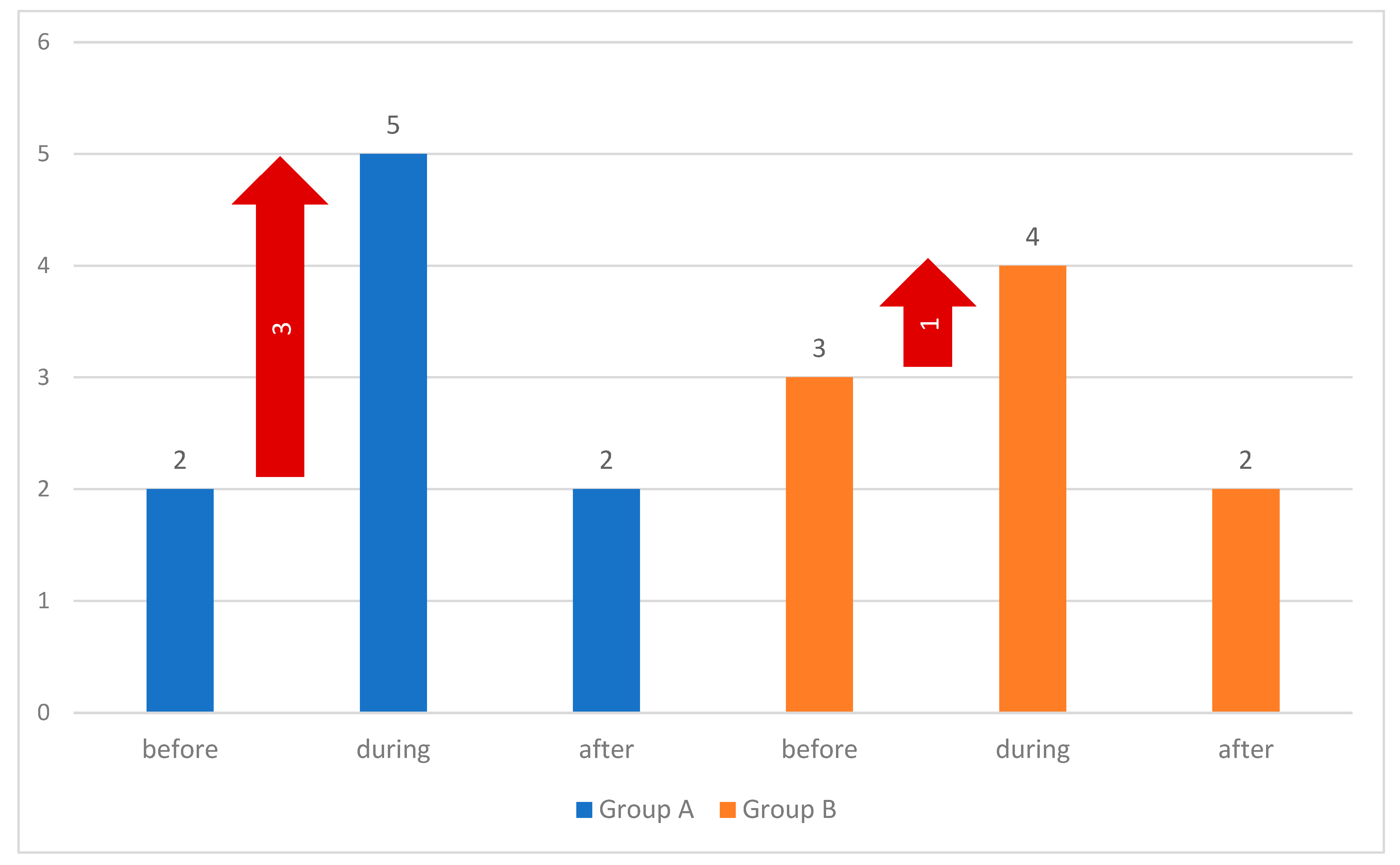

| 10 min Before Wound Debridement | Group | ||

| Total | Group A | Group B | |

| Average | 2.30 | 2.00 | 2.60 |

| SD | 1.60 | 1.53 | 1.63 |

| Median | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Min | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Max | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Q1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| n | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| During Wound Debridement | Group | ||

| Total | Group A | Group B | |

| Average | 4.63 | 4.94 | 4.32 |

| SD | 1.89 | 1.53 | 2.17 |

| Median | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Min | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Max | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| Q1 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Q3 | 5 | 6 | 5 |

| n | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| 10 min After Wound Debridement | Group | ||

| Total | Group A | Group B | |

| Average | 2.30 | 2.24 | 2.36 |

| SD | 1.56 | 1.41 | 1.71 |

| Median | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Min | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Max | 9 | 5 | 9 |

| Q1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| n | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| Time of Measurement | Group | Kolmogorov–Smirnov | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | df | Significance | ||

| 10 min before | Group A—no goggles | 0.240 | 50 | 0.000 |

| Group B—goggles | 0.157 | 50 | 0.003 | |

| During | Group A—no goggles | 0.204 | 50 | 0.000 |

| Group B—goggles | 0.197 | 50 | 0.000 | |

| 10 min after | Group A—no goggles | 0.148 | 50 | 0.008 |

| Group B—goggles | 0.194 | 50 | 0.000 | |

| NRS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 min Before | During | 10 min After | |

| Mann–Whitney U | 945.000 | 968.000 | 1241.500 |

| Wilcoxon W | 2220.000 | 2243.000 | 2516.500 |

| Z-score | −2.142 | −1.985 | −0.060 |

| Asymptotic significance (two-sided) | 0.032 | 0.047 | 0.952 |

| Effect size (rank-biserial correlation) | 0.244 | 0.226 | 0.007 |

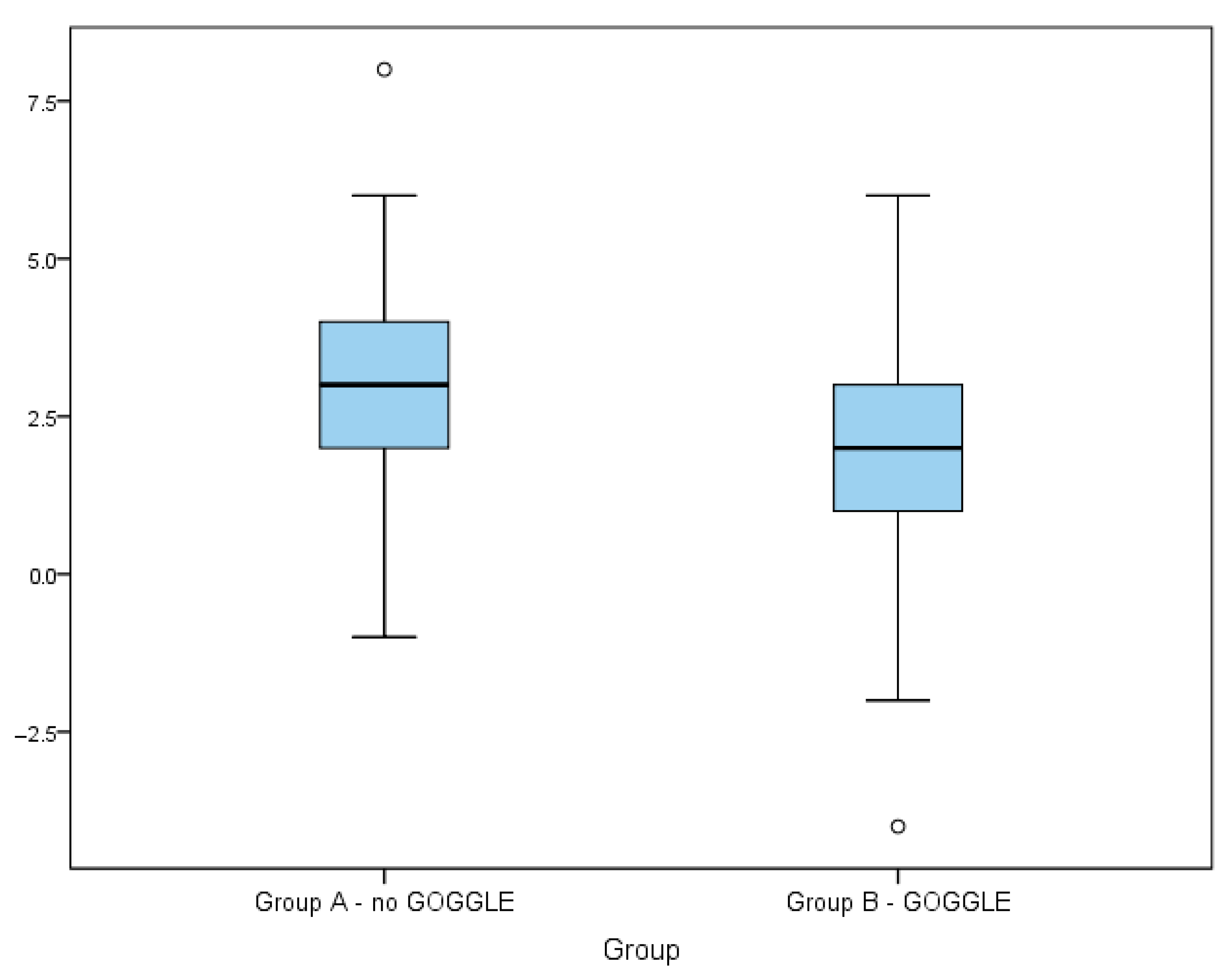

| NRS During—NRS Before Debridement | Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Group A | Group B | |

| Average | 2.33 | 2.94 | 1.72 |

| SD | 2.11 | 1.85 | 2.20 |

| Confidence interval | 1.91–2.75 | 2.42–3.46 | 1.09–2.35 |

| Median | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Min | −4 | −1 | −4 |

| Max | 8 | 8 | 6 |

| Q1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Q3 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| n | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| Difference Between Groups A and B | Difference Between NRS During and Before Debridement |

|---|---|

| Mann–Whitney U | 854.000 |

| Wilcoxon W | 2129.000 |

| Z | −2.767 |

| Asymptotic significance (two-sided) | 0.006 |

| Effect size (rank-biserial correlation) | 0.32 |

| NRS | Group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A—No Goggles | Group B—Goggles | |||||||

| Wound Type | Wound Type | |||||||

| Venous Leg Ulcer (VLU) | Mixed Ulcer | Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD) | Other | Venous Leg Ulcer (VLU) | Mixed Ulcer | Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD) | Other | |

| Average | 2.38 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 2.50 | 2.43 | 2.80 | 4.00 | 2.67 |

| SD | 1.77 | 1.05 | 1.14 | 2.38 | 1.77 | 1.42 | 1.63 | |

| Median | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Min | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Max | 7 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Q1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Q3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| n | 21 | 20 | 5 | 4 | 28 | 15 | 1 | 6 |

| K-W test | H(3) = 2.482, p = 0.479 | H(3) = 1.400, p = 0.705 | ||||||

| Rho Spearman | Group A | Group B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Assessment Acc. to the NRS Scale 10 min Before Wound Debridement | Wound Onset Time | Wound Extent in cm2 | Wound Onset Time | Wound Extent in cm2 |

| Correlation coefficient | 0.009 | −0.195 | −0.106 | −0.174 |

| Significance (two-sided) | 0.951 | 0.175 | 0.466 | 0.228 |

| n | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| 10 min Before | During | 10 min After | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mann–Whitney U | 1025.000 | 1233.000 | 1200.000 |

| Wilcoxon’s W | 2351.000 | 2458.000 | 2425.000 |

| Z-score | −1.577 | −0.116 | −0.349 |

| Asymptotic significance (two-sided) | 0.115 | 0.908 | 0.727 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bazaliński, D.; Wójcik, A.; Pytlak, K.; Bryła, J.; Kąkol, E.; Majka, D.; Dzień, J. The Use of Virtual Reality as a Non-Pharmacological Approach for Pain Reduction During the Debridement and Dressing of Hard-to-Heal Wounds. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4229. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124229

Bazaliński D, Wójcik A, Pytlak K, Bryła J, Kąkol E, Majka D, Dzień J. The Use of Virtual Reality as a Non-Pharmacological Approach for Pain Reduction During the Debridement and Dressing of Hard-to-Heal Wounds. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(12):4229. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124229

Chicago/Turabian StyleBazaliński, Dariusz, Anna Wójcik, Kamila Pytlak, Julia Bryła, Ewa Kąkol, Dawid Majka, and Julia Dzień. 2025. "The Use of Virtual Reality as a Non-Pharmacological Approach for Pain Reduction During the Debridement and Dressing of Hard-to-Heal Wounds" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 12: 4229. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124229

APA StyleBazaliński, D., Wójcik, A., Pytlak, K., Bryła, J., Kąkol, E., Majka, D., & Dzień, J. (2025). The Use of Virtual Reality as a Non-Pharmacological Approach for Pain Reduction During the Debridement and Dressing of Hard-to-Heal Wounds. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(12), 4229. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124229