The Impact of a Formalized Fertility Preservation Program on Access to Care and Sperm Cryopreservation Among Transgender and Nonbinary Patients Assigned Male at Birth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fertility Preservation Program Development and Workflow

2.2. Study Variables and Outcomes of Interest

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flores, A.R.; Herman, J.; Gates, G.J.; Brown, T.N. How Many Adults Identify as Transgender in the United States? The Williams Institute, University of California Los Angeles School of Law: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, P.J.; Pastuszak, A.W.; Myers, J.B.; Goodwin, I.A.; Hotaling, J.M. Fertility concerns of the transgender patient. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2019, 8, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Nie, I.; Mulder, C.L.; Meißner, A.; Schut, Y.; Holleman, E.M.; van der Sluis, W.B.; Hannema, S.E.; den Heijer, M.; Huirne, J.; van Pelt, A.M.M.; et al. Histological study on the influence of puberty suppression and hormonal treatment on developing germ cells in transgender women. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 37, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E.; Radix, A.E.; Bouman, W.P.; Brown, G.R.; de Vries, A.L.C.; Deutsch, M.B.; Ettner, R.; Fraser, L.; Goodman, M.; Green, J.; et al. Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8. Int. J. Transgender Health 2022, 23, S1–S259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine Access to fertility services by transgender and nonbinary persons: An Ethics Committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 115, 874–878. [CrossRef]

- Hembree, W.C.; Cohen-Kettenis, P.T.; Gooren, L.; Hannema, S.E.; Meyer, W.J.; Murad, M.H.; Rosenthal, S.M.; Safer, J.D.; Tangpricha, V.; T’Sjoen, G.G. Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society* Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 3869–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auer, M.K.; Fuss, J.; Nieder, T.O.; Briken, P.; Biedermann, S.V.; Stalla, G.K.; Beckmann, M.W.; Hildebrandt, T. Desire to Have Children Among Transgender People in Germany: A Cross-Sectional Multi-Center Study. J. Sex. Med. 2018, 15, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowski, A.S.; Fisher, A.R.; Jungheim, E.S.; Lewis, C.S.; Omurtag, K.R. Fertility preservation discussions, referral and follow-up in male-to-female and female-to-male adolescent transgender patients. Hum. Fertil. 2021, 26, 903–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Wallberg, K.; Obedin-Maliver, J.; Taylor, B.; Van Mello, N.; Tilleman, K.; Nahata, L. Reproductive health in transgender and gender diverse individuals: A narrative review to guide clinical care and international guidelines. Int. J. Transgender Health 2023, 24, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, J.; Garcia, M.M. Fertility preservation options for transgender individuals. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2020, 9, S215–S226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereecke, G.; Defreyne, J.; Van Saen, D.; Collet, S.; Van Dorpe, J.; T’Sjoen, G.; Goossens, E. Characterisation of testicular function and spermatogenesis in transgender women. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 36, deaa254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Wallberg, K.A.; Häljestig, J.; Arver, S.; Johansson, A.L.V.; Lundberg, F.E. Sperm quality in transgender women before or after gender affirming hormone therapy-A prospective cohort study. Andrology 2021, 9, 1773–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Kyweluk, M.A.; Sajwani, A.; Gordon, E.J.; Johnson, E.K.; Finlayson, C.A.; Woodruff, T.K. Factors Affecting Fertility Decision-Making Among Transgender Adolescents and Young Adults. LGBT Health 2019, 6, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiniara, L.N.; Viner, C.; Palmert, M.; Bonifacio, H. Perspectives on fertility preservation and parenthood among transgender youth and their parents. Arch. Dis. Child. 2019, 104, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleye, A.J.; Reid, G.; Kao, C.-N.; Mok-Lin, E.; Smith, J.F. Semen Parameters Among Transgender Women with a History of Hormonal Treatment. Urology 2019, 124, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Mei, L.; Ferrando, C. The effect of estrogen therapy on spermatogenesis in transgender women. FS Rep. 2021, 2, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheth, K.R.; Sharma, V.; Helfand, B.T.; Cashy, J.; Smith, K.; Hedges, J.C.; Köhler, T.S.; Woodruff, T.K.; Brannigan, R.E. Improved Fertility Preservation Care for Male Patients with Cancer After Establishment of Formalized Oncofertility Program. J. Urol. 2012, 187, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen, 5th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gabel, R.; Zalewski, M.; Moeller, A.; Halpin, M.; Tabares, S.; Castro, C.; Koehler, D.; Aquino, O.; Andersson, S.; Cassidy, K.; et al. Illinois House Bill 2617; INS CD-FERTILITY PRESERVATION; Illinois State Legislature: Springfield, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Amir, H.; Yaish, I.; Oren, A.; Groutz, A.; Greenman, Y.; Azem, F. Fertility preservation rates among transgender women compared with transgender men receiving comprehensive fertility counselling. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2020, 41, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpern, S.; Yaish, I.; Wagner-Kolasko, G.; Greenman, Y.; Sofer, Y.; Paltiel Lifshitz, D.; Groutz, A.; Azem, F.; Amir, H. Why fertility preservation rates of transgender men are much lower than those of transgender women. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2022, 44, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baram, S.; Myers, S.A.; Yee, S.; Librach, C.L. Fertility preservation for transgender adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. Hum. Reprod. Update 2019, 25, 694–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, N.; Douglas, C.R.; Mann, C.; Weimer, A.K.; Quinn, M.M. Access, barriers, and decisional regret in pursuit of fertility preservation among transgender and gender-diverse individuals. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 115, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadgauda, A.S.; Butts, S. Barriers to fertility preservation access in transgender and gender diverse adolescents: A narrative review. Ther. Adv. Reprod. Health 2024, 18, 26334941231222120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persky, R.W.; Gruschow, S.M.; Sinaii, N.; Carlson, C.; Ginsberg, J.P.; Dowshen, N.L. Attitudes Toward Fertility Preservation Among Transgender Youth and Their Parents. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2020, 67, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlegel, P.N.; Sigman, M.; Collura, B.; De Jonge, C.J.; Eisenberg, M.L.; Lamb, D.J.; Mulhall, J.P.; Niederberger, C.; Sandlow, J.I.; Sokol, R.Z.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of infertility in men: AUA/ASRM guideline part I. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 115, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, J.A.; Thirumavalavan, N.; Kohn, T.P.; Patel, A.S.; Leong, J.Y.; Cervellione, R.M.; Keene, D.J.B.; Ibrahim, E.; Brackett, N.L.; Lamb, D.J.; et al. Distribution of Semen Parameters Among Adolescent Males Undergoing Fertility Preservation in a Multicenter International Cohort. Urology 2019, 127, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, E.; Abhari, S.; Tangpricha, V.; Futral, C.; Mehta, A. Family Planning and Fertility Counseling Perspectives of Gender Diverse Adults and Youth Pursuing or Receiving Gender Affirming Hormone Therapy. Urology 2023, 171, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

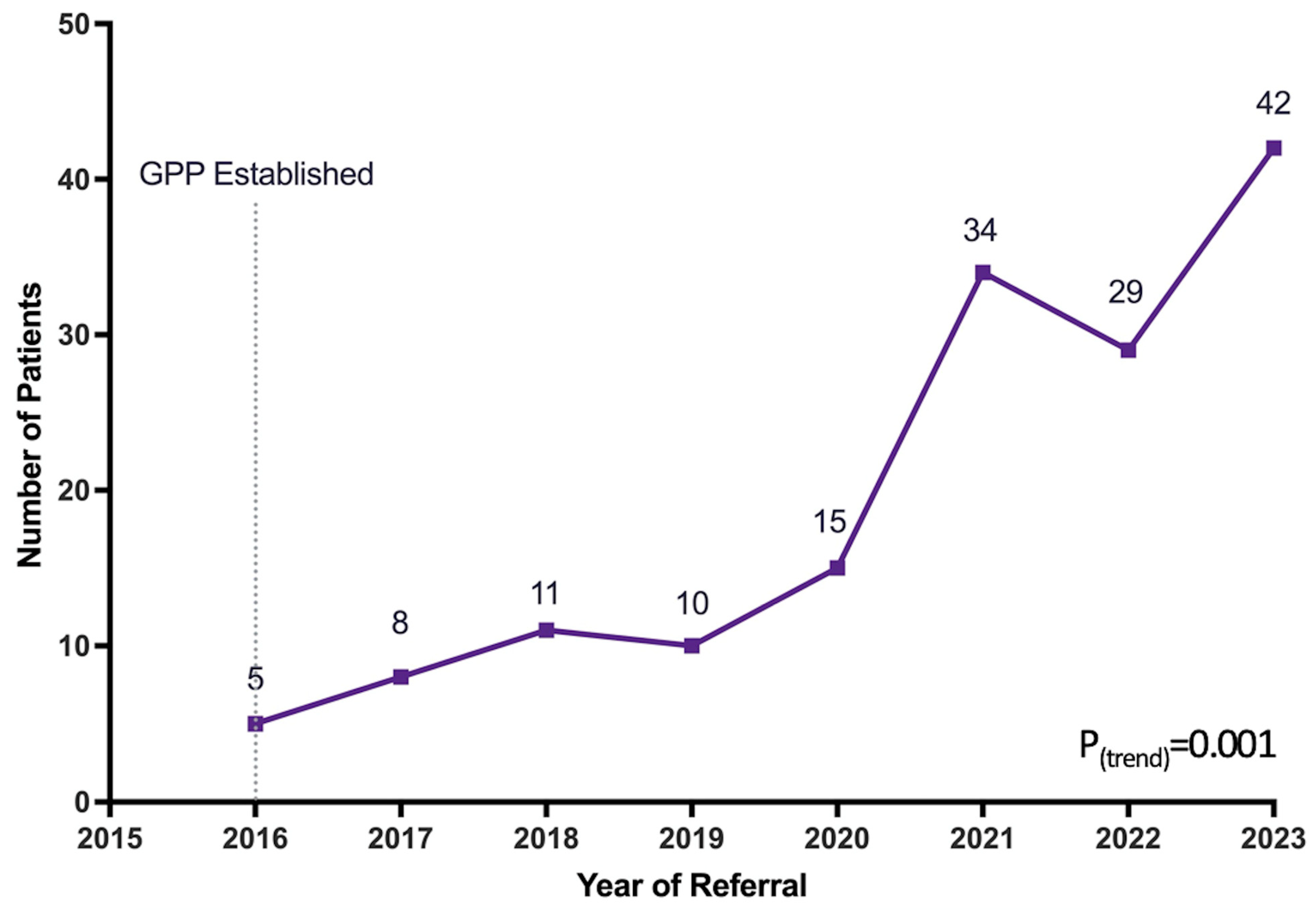

| Year | Total Referrals (N) | Completed Referrals (n, %) * | Samples Provided (n, %) * |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 5 | 4 (80.0) | 4 (80.0) |

| 2017 | 8 | 8 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) |

| 2018 | 11 | 9 (81.8) | 8 (72.7) |

| 2019 | 10 | 8 (80.0) | 8 (80.0) |

| 2020 | 15 | 14 (93.3) | 12 (80.0) |

| 2021 | 34 | 32 (94.1) | 31 (91.2) |

| 2022 | 29 | 24 (82.8) | 23 (79.3) |

| 2023 | 42 | 32 (76.2) | 30 (71.4) |

| p-value | 0.001 | 0.22 | 0.24 |

| Overall (N = 154) | <18 Years Old (n = 71) | ≥18 Years Old (n = 83) | p-Value (<0.05) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at referral (years) | 20.5 ± 5.7 | 16.1 ± 1.6 | 24.3 ± 5.3 | <0.001 |

| Prior hormonal therapy | 36 (23.4) | 10 (14.1) | 26 (31.3) | 0.01 |

| Referral Characteristics | ||||

| Completed referral (saw MD/APP) | 131 (85.1) | 61 (85.9) | 70 (84.3) | 0.78 |

| Sperm banking | 124 (80.5) | 54 (76.1) | 70 (84.3) | 0.20 |

| Number of times banking | 2.1 ± 1.5 | 2.4 ± 1.4 | 1.9 ± 1.6 | 0.12 |

| Vials per bank | 4.4 ± 3.1 | 2.8 ± 2.2 | 5.7 ± 3.2 | <0.001 |

| Semen Parameters | ||||

| Ejaculate volume (mL) | 2.7 ± 1.7 | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 3.4 ± 1.7 | <0.001 |

| Sperm concentration (M/mL) | 36.0 ± 31.6 | 30.7 ± 29.5 | 40.1 ± 32.9 | 0.10 |

| Sperm motility (%) | 56.8 ± 19.0 | 53.9 ± 19.9 | 59.0 ± 18.0 | 0.13 |

| Sperm morphology (%) | 4.7 ± 2.9 | 4.0 ± 2.9 | 5.2 ± 2.7 | 0.03 |

| Total motile sperm count (M) | 61.4 ± 57.3 | 36.4 ± 41.1 | 80.9 ± 60.7 | <0.001 |

| Serum Hormonal Values | ||||

| Testosterone (ng/dL) | 407.4 ± 188.6 | 412.3 ± 184.5 | 402.7 ± 194.1 | 0.81 |

| FSH (mIU/mL) | 3.3 ± 3.4 | 2.9 ± 1.6 | 3.6 ± 4.6 | 0.48 |

| Prior GAHT (n = 30) | No Prior GAHT (n = 94) | p-Value (<0.05) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ejaculate volume (mL) | 2.7 ± 1.3 | 2.7 ± 1.8 | 0.95 |

| Sperm concentration (M/mL) | 26.8 ± 23.5 | 38.1 ± 33.5 | 0.09 |

| Sperm motility (%) | 51.5 ± 20.2 | 58.5 ± 18.4 | 0.08 |

| Sperm morphology (%) | 4.2 ± 3.3 | 4.8 ± 2.8 | 0.24 |

| Total motile sperm count (M) | 51.2 ± 63.3 | 62.7 ± 55.4 | 0.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Greenberg, D.R.; Longi, F.N.; Cromack, S.C.; Smith, K.N.; Brown, V.G.; Bazzetta, S.E.; Goldman, K.N.; Brannigan, R.E.; Halpern, J.A. The Impact of a Formalized Fertility Preservation Program on Access to Care and Sperm Cryopreservation Among Transgender and Nonbinary Patients Assigned Male at Birth. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4203. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124203

Greenberg DR, Longi FN, Cromack SC, Smith KN, Brown VG, Bazzetta SE, Goldman KN, Brannigan RE, Halpern JA. The Impact of a Formalized Fertility Preservation Program on Access to Care and Sperm Cryopreservation Among Transgender and Nonbinary Patients Assigned Male at Birth. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(12):4203. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124203

Chicago/Turabian StyleGreenberg, Daniel R., Faraz N. Longi, Sarah C. Cromack, Kristin N. Smith, Valerie G. Brown, Sarah E. Bazzetta, Kara N. Goldman, Robert E. Brannigan, and Joshua A. Halpern. 2025. "The Impact of a Formalized Fertility Preservation Program on Access to Care and Sperm Cryopreservation Among Transgender and Nonbinary Patients Assigned Male at Birth" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 12: 4203. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124203

APA StyleGreenberg, D. R., Longi, F. N., Cromack, S. C., Smith, K. N., Brown, V. G., Bazzetta, S. E., Goldman, K. N., Brannigan, R. E., & Halpern, J. A. (2025). The Impact of a Formalized Fertility Preservation Program on Access to Care and Sperm Cryopreservation Among Transgender and Nonbinary Patients Assigned Male at Birth. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(12), 4203. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124203