Exploring the Role of Autologous Fat Grafting in Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction: A Systematic Review of Complications and Aesthetic Results

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature and Search Strategy

2.2. Information Source and Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Adult female patient over 18 years;

- Studies published in English;

- The full text was available;

- Study type;

- Fat grafting secondary to breast implant reconstruction;

- Fat grafting during same procedure as implant reconstruction or before;

- Follow up period of at least 3 months;

- Study included outcome of complications or aesthetic satisfaction (or both);

- Patients with chronic disease.;

- Studies which were published in a language other than English;

- Studies with no data on complications or aesthetic outcome;

- Single case reports;

- Studies reporting about breast reconstruction with exclusive fat grafting only;

- Studies that do not demonstrate original data, such as meta-analyses, systematic reviews, or discussions;

- In vivo studies on animals or in vitro studies.

2.4. Selection Process

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

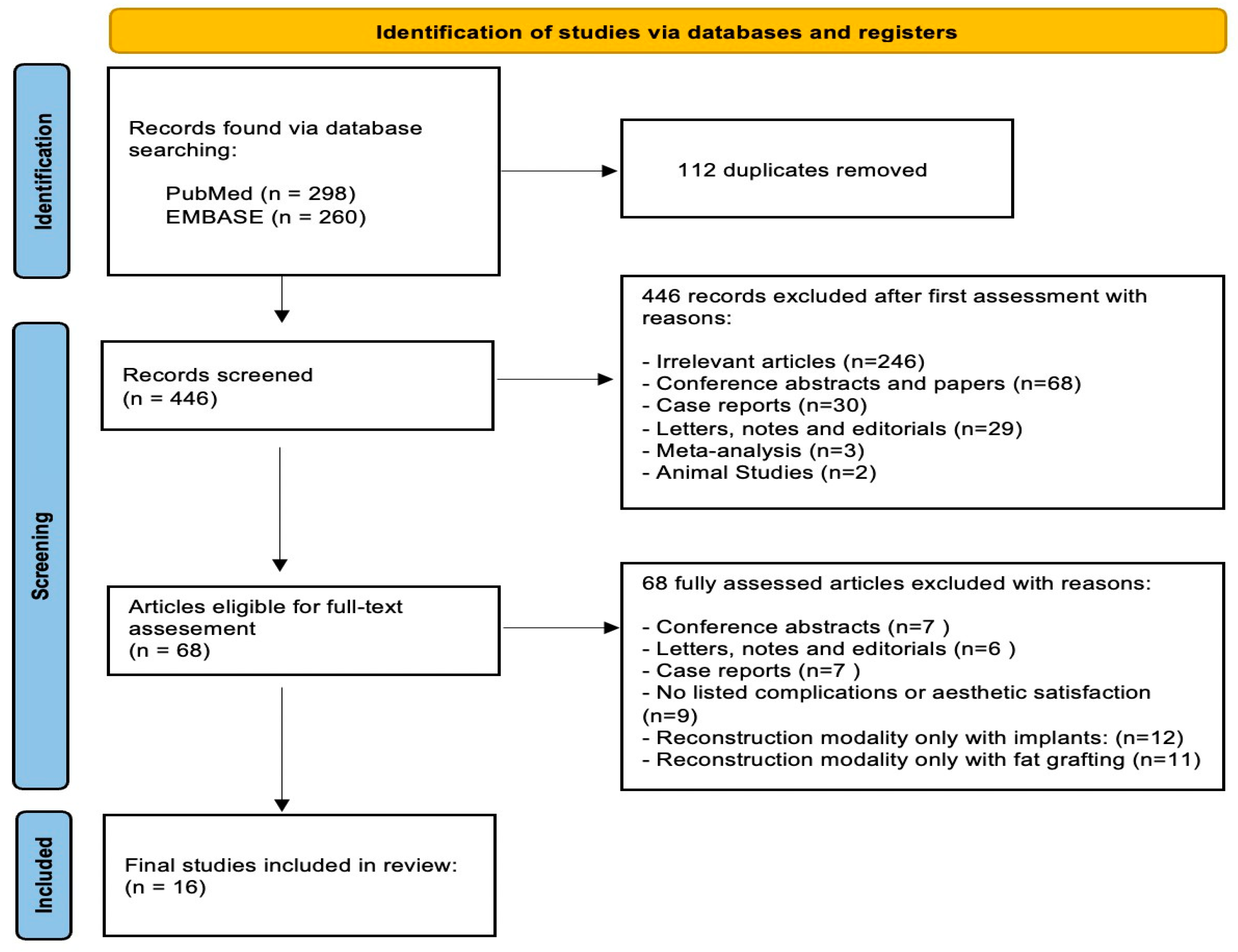

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Patient Characteristics

3.4. Fat Grafting

3.5. Complications

3.6. Aesthetic Score

3.7. Risk of Bias Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Main Results

4.2. Applicability of Evidence

4.3. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IBR | Implant based breast reconstruction |

| HBR | Hybrid breast reconstruction |

| FG | Fat Grafting |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| TE | Tissue expander |

References

- Allen Gabriel, M.Y.N. Spear’s Surgery of the Breast: Principles and Art, 4th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, A.; Abu-Ghname, A.; Davis, M.J.; Winocour, S.J.; Hanson, S.E.; Chu, C.K. Fat Grafting in Breast Reconstruction. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2020, 34, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, S.; Zingaretti, N.; De Francesco, F.; Riccio, M.; De Biasio, F.; Massarut, S.; Almesberger, D.; Parodi, P.C. Long-term impact of lipofilling in hybrid breast reconstruction: Retrospective analysis of two cohorts. Eur. J. Plast. Surg. 2020, 43, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delay, E.; Garson, S.; Tousson, G.; Sinna, R. Fat injection to the breast: Technique, results, and indications based on 880 procedures over 10 years. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2009, 29, 360–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.A.; Martin, S.A.; Cheesborough, J.E.; Lee, G.K.; Nazerali, R.S. The safety and efficacy of autologous fat grafting during second stage breast reconstruction. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2021, 74, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, D.C.; O’Connor, E.A.; Scheer, J.R. Total envelope fat grafting: A novel approach in breast reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 135, 691–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillaert, F.B. The prepectoral, hybrid breast reconstruction: The synergy of lipofilling and breast implants. In Plastic and Aesthetic Regenerative Surgery and Fat Grafting: Clinical Application and Operative Techniques; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1181–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Gronovich, Y.; Winder, G.; Maisel-Lotan, A.; Lysy, I.; Sela, E.; Spiegel, G.; Carmon, M.; Hadar, T.; Elami, A.; Eizenman, N.; et al. Hybrid Prepectoral Direct-to-Implant and Autologous Fat Graft Simultaneously in Immediate Breast Reconstruction: A Single Surgeon’s Experience with 25 Breasts in 15 Consecutive Cases. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 149, 386e–391e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommeling, C.E.; Van Landuyt, K.; Depypere, H.; Van den Broecke, R.; Monstrey, S.; Blondeel, P.N.; Morrison, W.A.; Stillaert, F.B. Composite breast reconstruction: Implant- based breast reconstruction with adjunctive lipofilling. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2017, 70, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogliandro, A.; Barone, M.; Tenna, S.; Morelli Coppola, M.; Persichetti, P. The role of lipofilling after breast reconstruction: Evaluation of outcomes and patient satisfaction with BREAST-Q. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2017, 41, 1325–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigna, E.; Monfrecola, A. Secondary lipofilling after breast reconstruction with implants. In Breast Reconstruction: Art, Science, and New Clinical Techniques; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 305–312. [Google Scholar]

- Salgarello, M.; Visconti, G.; Barone-Adesi, L. Fat grafting and breast reconstruction with implant: Another option for irradiated breast cancer patients. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012, 129, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfati, I.; Ihrai, T.; Kaufman, G.; Nos, C.; Clough, K. Adipose-tissue grafting to the post-mastectomy irradiated chest wall: Preparing the ground for implant reconstruction. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2011, 64, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzouk, K.; Humbert, P.; Borens, B.; Gozzi, M.; Al Khori, N.; Pasquier, J.; Rafii Tabrizi, A. Skin trophicity improvement by mechanotherapy for lipofilling- based breast reconstruction postradiation therapy. Breast J. 2020, 26, 725–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razzouk, K.; Fitoussi, A.; Al Khori, N.; Pasquier, J.; Chouchane, L.; Tabrizi, A.R. Breast reconstruction combining lipofilling and prepectoral prosthesis after radiotherapy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.-Glob. Open 2020, 8, e2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra-Renom, J.M.; Muñoz-Olmo, J.L.; Serra-Mestre, J.M. Fat grafting in postmastectomy breast reconstruction with expanders and prostheses in patients who have received radiotherapy: Formation of new subcutaneous tissue. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 125, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhiani, C.; Hammoudeh, Z.S.; Aho, J.M.; Lee, M.; Rasko, Y.; Cheng, A.; Saint-Cyr, M. Maximizing aesthetic outcome in autologous breast reconstruction with implants and lipofilling. Eur. J. Plast. Surg. 2014, 37, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyaya, S.N.; Bernard, S.L.; Grobmyer, S.R.; Yanda, C.; Tu, C.; Valente, S.A. Outcomes of autologous fat grafting in mastectomy patients following breast reconstruction. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 25, 3052–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoc, C.H.; Dias, L.P.N.; Braghiroli, O.F.M.; Martella, N.; Giovinazzo, V.; Piat, J.M. Oncological safety of lipofilling in healthy BRCA carriers after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy: A case series. Eur. J. Breast Health 2019, 15, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albornoz, C.R.; Bach, P.B.; Mehrara, B.J.; Disa, J.J.; Pusic, A.L.; McCarthy, C.M.; Cordeiro, P.G.; Matros, E. A paradigm shift in US breast reconstruction: Increasing implant rates. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 131, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhaveri, J.D.; Rush, S.C.; Kostroff, K.; Derisi, D.; Farber, L.A.; Maurer, V.E.; Bosworth, J.L. Clinical outcomes of postmastectomy radiation therapy after immediate breast reconstruction. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2008, 72, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahabedian, M.Y. Plastic Surgery Breast, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Ribuffo, D.; Atzeni, M.; Guerra, M.; Bucher, S.; Politi, C.; Deidda, M.; Atzori, F.; Dessi, M.; Madeddu, C.; Lay, G. Treatment of irradiated expanders: Protective lipofilling allows immediate prosthetic breast reconstruction in the setting of postoperative radiotherapy. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2013, 37, 1146–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, S.L.; Coles, C.N.; Leung, B.K.; Gitlin, M.; Parekh, M.; Macarios, D. The safety, effectiveness, and efficiency of autologous fat grafting in breast surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.-Glob. Open 2016, 4, e827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviggioli, F.; Maione, L.; Forcellini, D.; Klinger, F.; Klinger, M. Autologous fat graft in postmastectomy pain syndrome. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011, 128, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.S.; Ng, Z.Y.; Zhan, W.; Rozen, W. Role of Adipose-derived Stem Cells in Fat Grafting and Reconstructive Surgery. J. Cutan. Aesthetic Surg. 2016, 9, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Karam, M.; Abul, A.; Rahman, S. Stem Cell Enriched Fat Grafts versus Autologous Fat Grafts in Reconstructive Surgery: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2023, 47, 2754–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Parameters | Inclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Participants | Female participants, clinically healthy, aged ≥ 18 years |

| Intervention | Implant breast reconstruction with autologous fat grafting |

| Comparison | Implant breast reconstruction alone |

| Outcome | Complications, aesthetic satisfaction |

| Study design | Case series, case–control, retrospective |

| Authors | Study Title | Year | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patel et al. [5] | The safety and efficacy of autologous fat grafting during second stage breast reconstruction | 2021 | United States |

| Hammond et al. [6] | Total envelope fat grafting: A novel approach in breast reconstruction | 2015 | United States |

| Stillaert et al. [7] | The Prepectoral, Hybrid Breast Reconstruction: The Synergy of Lipofilling and Breast Implants | 2020 | United States |

| Gronovich et al. [8] | Hybrid Prepectoral Direct-to-Implant and Autologous Fat Graft Simultaneously in Immediate Breast Reconstruction: A Single Surgeon’s Experience with 25 Breasts in 15 Consecutive Cases | 2022 | Israel |

| Sommeling et al. [9] | Composite breast reconstruction: Implant-based breast reconstruction with adjunctive lipofilling | 2017 | Belgium |

| Cogliandro et al. [10] | The Role of Lipofilling After Breast Reconstruction: Evaluation of Outcomes and Patient Satisfaction with BREAST-Q | 2017 | Italy |

| Cigna et al. [11] | Secondary lipofilling after breast reconstruction with implants | 2016 | Italy |

| Salgarello et al. [12] | Fat grafting and breast reconstruction with implant: Another option for irradiated breast cancer patients | 2012 | Greece |

| Sarfati et al. [13] | Adipose-tissue grafting to the post-mastectomy irradiated chest wall: Preparing the ground for implant reconstruction | 2011 | France |

| Razzouk et al. [14] | Skin trophicity improvement by mechanotherapy for lipofilling-based breast reconstruction postradiation therapy | 2020 | France |

| Razzouk et al. [15] | Breast Reconstruction Combining Lipofilling and Prepectoral Prosthesis after Radiotherapy | 2020 | France |

| Serra-Renom et al. [16] | Fat grafting in postmastectomy breast reconstruction with expanders and prostheses in patients who have received radiotherapy: Formation of new subcutaneous tissue | 2010 | Spain |

| Lakhiani et al. [17] | Maximizing aesthetic outcome in autologous breast reconstruction | 2014 | United States |

| Upadhyaya et al. [18] | Outcomes of Autologous Fat Grafting in Mastectomy Patients Following Breast Reconstruction | 2018 | United States |

| Author | Study Type | Patients (Mean Age) | RT (%) | Technique | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patel et al. [5] | Case–Control | 157 (48.2) | 31% | TE → IBR + FG (Immediate/Delayed) | Immediate FG reduces complications and surgical burden vs. delayed. |

| Hammond et al. [6] | Case Series | 22 (47) | N/A | IBR + Immediate FG | Reliable technique with low complications. |

| Stillaert et al. [7] | Case Series | 33 (42) | 3% | TE → FG → Prepectoral IBR | Improves outcomes and reduces tissue strain. |

| Gronovich et al. [8] | Case Series | 15 (44) | 27% | Immediate IBR + FG | Hybrid IBR improves contour, reduces rippling and reoperation. |

| Sommeling et al. [9] | Case Series | 15 (46) | 40% | TE → FG → Prepectoral IBR | Improved aesthetics, requires multiple stages. |

| Cogliandro et al. [10] | Case–Control | 46 (41) | 74% | IBR → Delayed FG | FG improves aesthetic and psychological outcomes post-RT. |

| Cigna et al. [11] | Case Series | 20 (65) | 0% | IBR → Delayed FG | FG effective for contour correction with minimal morbidity. |

| Salgarello et al. [12] | Case Series | 16 (41) | 100% | FG → IBR | Pre-implant FG mitigates RT-related implant issues. |

| Sarfati et al. [13] | Case Series | 28 (45) | 100% | FG → IBR | >80% good/very good results; no capsular contracture. |

| Razzouk et al. [14] | Retrospective | 32 (50.6) | 100% | FG → Prepectoral IBR | FG improves flap thickness and skin quality. |

| Razzouk et al. [15] | Retrospective | 136 (52) | 100% | FG → Prepectoral IBR | Higher FG volume → smaller implants, improved skin trophicity. |

| Serra-Renom et al. [16] | Case Series | 65 (65) | 100% | TE + FG → IBR + FG | FG improves skin quality, prevents contracture. |

| Lakhiani et al. [17] | Retrospective | 24 (N/A) | N/A | FG → IBR | Higher aesthetic scores in hybrid group. |

| Upadhyaya et al. [18] | Retrospective | 171 (50.5) | N/A | TE → IBR + FG | Fat necrosis risk increases with higher volume (10.5%). |

| Ho Quoc et al. [19] | Case Series | 18 (43.8) | N/A | IBR → FG | No recurrence; minor complications only. |

| Calabrese et al. [3] | Case–Control | 84 FG + IBR, 130 IBR | 26% | TE → IBR ± FG | FG group had lower contracture rate and better aesthetics. |

| Author | Study Type | Patients (Mean Age) | Mean Volume (mL) | Fat Grafting Sessions (Mean, Range) | Aesthetic Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patel et al. [5] | Case–Control | 157 (48.2) | 94 | 2.7 (1–5) | N/A |

| Hammond et al. [6] | Case Series | 22 (47) | 134 | 1.4 (1–2) | N/A |

| Stillaert et al. [7] | Case Series | 33 (42) | 262 | 2.7 (1–5) | N/A |

| Gronovich et al. [8] | Case Series | 15 (44) | 59.8 | 1 | N/A |

| Sommeling et al. [9] | Case Series | 15 (46) | 313 | 3.2 (2–5) | N/A |

| Cogliandro et al. [10] | Case–Control | 46 (41) | 110 | 2.2 (1–3) | N/A |

| Cigna et al. [11] | Case Series | 20 (65) | N/A | 1 | N/A |

| Salgarello et al. [12] | Case Series | 16 (41) | 95.7 | 2.4 (1–4) | N/A |

| Sarfati et al. [13] | Case Series | 28 (45) | 115 | 2 (1–3) | 4.5 (3.5–5) |

| Razzouk et al. [14] | Retrospective | 32 (50.6) | 151 | 1.15 (1–3) | 4.8 |

| Razzouk et al. [15] | Retrospective | 136 (52) | 220 | 1.6 (1–3) | 4.8 |

| Serra-Renom et al. [16] | Case Series | 65 (65) | 140 | 2.4 (1–4) | 4 |

| Lakhiani et al. [17] | Retrospective | 24 (N/A) | 168.6 | 1.4 (1–3) | 4 |

| Upadhyaya et al. [18] | Retrospective | 171 (50.5) | 132 | 1.18 (1–3) | N/A |

| Ho Quoc et al. [19] | Case Series | 18 (43.8) | 107 | 1.3 | N/A |

| Calabrese et al. [3] | Case–Control | 84 FG + IBR, 130 IBR | 88 | N/A | N/A |

| Author | Study Type | Patients (Mean Age) | Total Complications | Minor Complications | Major Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patel et al. [5] | Case–Control | 157 (48.2) | 20 | 13 (4 infections, 6 dehiscence, 4 seromas, 1 fat necrosis, 2 implant malposition) | 7 (4 infections, 3 skin necrosis) |

| Hammond et al. [6] | Case Series | 22 (47) | 4 | 3 (2 fat necrosis, 1 dehiscence) | 1 (1 red breast) |

| Stillaert et al. [7] | Case Series | 33 (42) | 4 | 1 (1 haematoma) | 3 (1 TE infection, 2 implant infections) |

| Gronovich et al. [8] | Case Series | 15 (44) | 5 | 3 (2 seromas, 1 dehiscence) | 2 (2 infections) |

| Sommeling et al. [9] | Case Series | 15 (46) | 1 | 0 | 1 (1 implant infection with fat necrosis) |

| Cogliandro et al. [10] | Case–Control | 46 (41) | 2 | 0 | 2 (1 infection, 1 implant rupture) |

| Cigna et al. [11] | Case Series | 20 (65) | 1 | 1 (1 fat necrosis) | 0 |

| Salgarello et al. [12] | Case Series | 16 (41) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sarfati et al. [13] | Case Series | 28 (45) | 4 | 3 (3 seromas) | 1 (1 severe seroma) |

| Razzouk et al. [14] | Retrospective | 32 (50.6) | 5 | 4 (4 cystic fat necrosis) | 1 (1 implant infection) |

| Razzouk et al. [15] | Retrospective | 136 (52) | 10 | 7 (7 cystic seromas) | 3 (1 implant infection, 2 skin necrosis) |

| Serra-Renom et al. [16] | Case Series | 65 (65) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lakhiani et al. [17] | Retrospective | 24 (N/A) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Upadhyaya et al. [18] | Retrospective | 171 (50.5) | 18 | 18 (12 fat necrosis in IBR, 6 in autologous) | 0 |

| Ho Quoc et al. [19] | Case Series | 18 (43.8) | 4 | 4 (4 hematomas) | 0 |

| Calabrese et al. [3] | Case–Control | 84 FG + IBR, 130 IBR | 3 | 2 (2 seromas) | 1 (1 implant infection) |

| Author | Study Type | Selection (4) | Comparability (2) | Outcome (3) | Total Score (9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patel et al. [5] | Case–Control | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Cogliandro et al. [10] | Case–Control | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Calabrese et al. [3] | Case–Control | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Lakhiani et al. [17] | Retrospective Cohort | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Upadhyaya et al. [18] | Retrospective Cohort | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Razzouk et al. [14] | Retrospective Cohort | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Razzouk et al. [15] | Retrospective Cohort | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Hammond et al. [6] | Case Series | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Stillaert et al. [7] | Case Series | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Gronovich et al. [8] | Case Series | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Sommeling et al. [9] | Case Series | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Cigna et al. [11] | Case Series | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Salgarello et al. [12] | Case Series | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Sarfati et al. [13] | Case Series | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Serra-Renom et al. [16] | Case Series | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Ho Quoc et al. [19] | Case Series | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muntean, M.V.; Pop, I.C.; Ilies, R.A.; Pelleter, A.; Vlad, I.C.; Achimas-Cadariu, P. Exploring the Role of Autologous Fat Grafting in Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction: A Systematic Review of Complications and Aesthetic Results. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4073. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124073

Muntean MV, Pop IC, Ilies RA, Pelleter A, Vlad IC, Achimas-Cadariu P. Exploring the Role of Autologous Fat Grafting in Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction: A Systematic Review of Complications and Aesthetic Results. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(12):4073. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124073

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuntean, Maximilian Vlad, Ioan Constantin Pop, Radu Alexandru Ilies, Annika Pelleter, Ioan Catalin Vlad, and Patriciu Achimas-Cadariu. 2025. "Exploring the Role of Autologous Fat Grafting in Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction: A Systematic Review of Complications and Aesthetic Results" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 12: 4073. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124073

APA StyleMuntean, M. V., Pop, I. C., Ilies, R. A., Pelleter, A., Vlad, I. C., & Achimas-Cadariu, P. (2025). Exploring the Role of Autologous Fat Grafting in Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction: A Systematic Review of Complications and Aesthetic Results. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(12), 4073. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14124073