Validation of the Italian Version of the Visual Function and Corneal Health Status (V-FUCHS) Questionnaire: A Patient-Reported Visual Disability Instrument for Fuchs’ Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Translation of the V-FUCHS Questionnaire

2.3. Physical Examination and Questionnaire Administration

2.4. Reliability and Validity Assessment

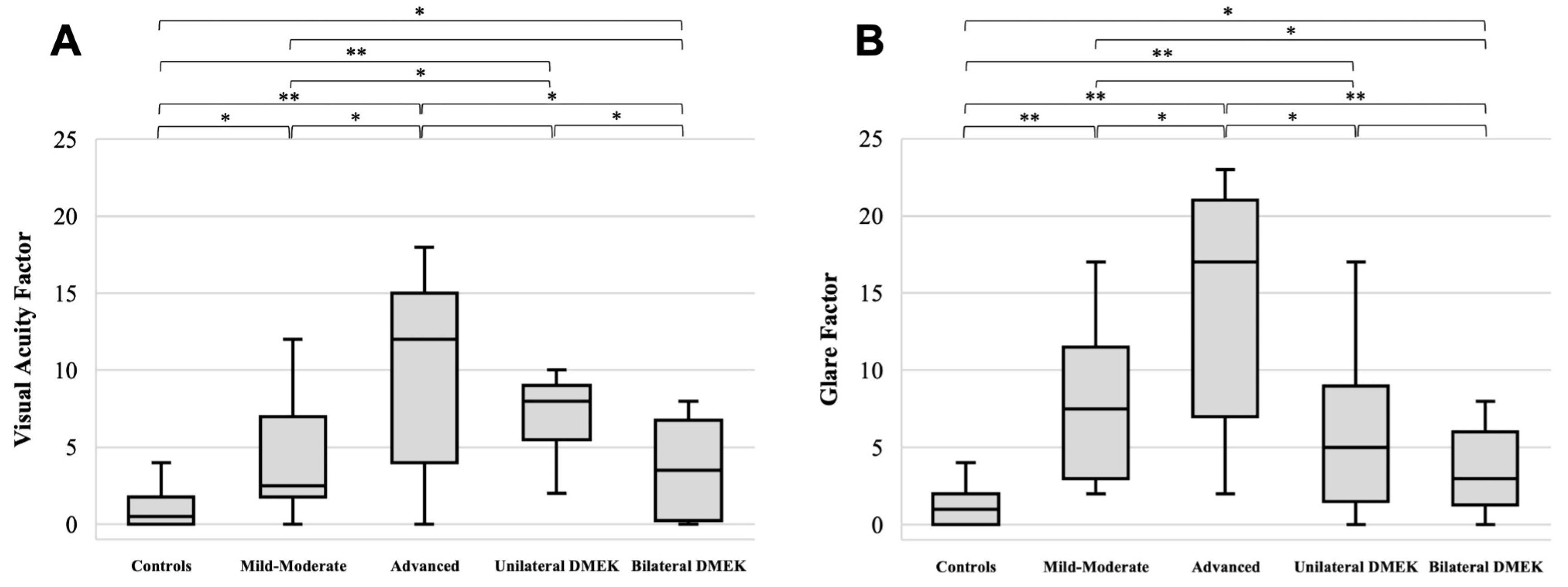

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altamirano, F.; Ortiz-Morales, G.; O’Connor-Cordova, M.A.; Sancén-Herrera, J.P.; Zavala, J.; Valdez-Garcia, J.E. Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy: An Updated Review. Int. Ophthalmol. 2024, 44, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gain, P.; Jullienne, R.; He, Z.; Aldossary, M.; Acquart, S.; Cognasse, F.; Thuret, G. Global Survey of Corneal Transplantation and Eye Banking. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016, 134, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, S.X.; Lee, W.B.; Hammersmith, K.M.; Kuo, A.N.; Li, J.Y.; Shen, J.F.; Weikert, M.P.; Shtein, R.M. Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty: Safety and Outcomes: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrerizo, J.; Livny, E.; Musa, F.U.; Leeuwenburgh, P.; Van Dijk, K.; Melles, G.R.J. Changes in Color Vision and Contrast Sensitivity after Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty for Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy. Cornea 2014, 33, 1010–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, C.; Oie, Y.; Nishida, N.; Doi, S.; Fujimoto, C.; Asonuma, S.; Maeno, S.; Soma, T.; Koh, S.; Jhanji, V.; et al. Associations Between Visual Functions and Severity Gradings, Corneal Scatter, or Higher-Order Aberrations in Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2024, 65, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Meulen, I.J.E.; Patel, S.V.; Lapid-Gortzak, R.; Nieuwendaal, C.P.; McLaren, J.W.; Van Den Berg, T.J.T.P. Quality of Vision in Patients with Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy and after Descemet Stripping Endothelial Keratoplasty. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2011, 129, 1537–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oie, Y.; Watanabe, S.; Nishida, K. Evaluation of Visual Quality in Patients with Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy. Cornea 2016, 35, S55–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, T.; Calvert, M.; Gray, A.; Pesudovs, K.; Denniston, A.K. The Use of Patient-Reported Outcome Research in Modern Ophthalmology: Impact on Clinical Trials and Routine Clinical Practice. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2019, 10, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.J.; Jones, L.; Edwards, L.; Crabb, D.P. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Ophthalmology: Too Difficult to Read? BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2021, 6, e000693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesudovs, K.; Burr, J.M.; Harley, C.; Elliott, D.B. The Development, Assessment, and Selection of Questionnaires. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2007, 84, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangione, C.M.; Lee, P.P.; Gutierrez, P.R.; Spritzer, K.; Berry, S.; Hays, R.D. Development of the 25-Item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2001, 119, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundström, M.; Pesudovs, K. Catquest-9SF Patient Outcomes Questionnaire. Nine-Item Short-Form Rasch-Scaled Revision of the Catquest Questionnaire. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2009, 35, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claesson, M.; Armitage, W.J.; Byström, B.; Montan, P.; Samolov, B.; Stenvi, U.; Lundström, M. Validation of Catquest-9SF-A Visual Disability Instrument to Evaluate Patient Function after Corneal Transplantation. Cornea 2017, 36, 1083–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wacker, K.; McLaren, J.W.; Kane, K.M.; Patel, S.V. Corneal Optical Changes Associated with Induced Edema in Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy. Cornea 2018, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M.; Grewing, V.; Maier, P.; Lapp, T.; Böhringer, D.; Reinhard, T.; Wacker, K. Diurnal Variation in Corneal Edema in Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 207, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacker, K.; Baratz, K.H.; Bourne, W.M.; Patel, S.V. Patient-Reported Visual Disability in Fuchs’ Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy Measured by the Visual Function and Corneal Health Status Instrument. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1854–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewing, V.; Fritz, M.; Müller, C.; Böhringer, D.; Reinhard, T.; Patel, S.V.; Wacker, K. The German Version of the Visual Function and Corneal Health Status (V-FUCHS): A Fuchs Dystrophy-Specific Visual Disability Instrument. Ophthalmologe 2020, 117, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torras-Sanvicens, J.; Rodríguez-Calvo-de-Mora, M.; Figueras-Roca, M.; Amescua, G.; Carletti, P.; Casaroli-Marano, R.P.; Patel, S.V.; Rocha-de-Lossada, C. Translation and Validation of the Visual Function and Corneal Health Status (V-FUCHS) Questionnaire into Spanish Language. Arch. Soc. Esp. Oftalmol. 2024, 99, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullie, G.A.; Juarez, A.; Etcheverry, A.; Natchev, P.; Taleb, N.; Boutin, T.; Choremis, J.; Mabon, M.; Talajic, J.; Giguère, C.-É.; et al. Validation of a French Version of the Visual Function and Corneal Health Status Instrument and Correlation with Vision and Glare Measurements in Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy. Cornea 2024, 44, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krachmer, J.H.; Purcell, J.J.; Young, C.W.; Bucher, K.D. Corneal Endothelial Dystrophy: A Study of 64 Families. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1978, 96, 2036–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louttit, M.D.; Kopplin, L.J.; Igo, R.P.; Fondran, J.R.; Tagliaferri, A.; Bardenstein, D.; Aldave, A.J.; Croasdale, C.R.; Price, M.O.; Rosenwasser, G.O.; et al. A Multicenter Study to Map Genes for Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy: Baseline Characteristics and Heritability. Cornea 2012, 31, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chylack, L.T.; Wolfe, J.K.; Singer, D.M.; Leske, M.C.; Bullimore, M.A.; Bailey, I.L.; Friend, J.; McCarthy, D.; Wu, S.Y. The Lens Opacities Classification System III. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1993, 111, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuliś, D.; Bottomley, A.; Velikova, G.; Greimel, E.; Koller, M. EORTC Quality of Life Group Translation Procedure, 4th ed.; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rash, G. On General Laws and the Meaning of Measurement in Psychology. In Proceedings of the Fourth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Volume 4: Contributions to Biology and Problems of Medicine; Statistical Laboratory of the University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Masters, G.N. A Rasch Model for Partial Credit Scoring. Psychometrika 1982, 47, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J.; Shavelson, R.J. My Current Thoughts on Coefficient Alpha and Successor Procedures. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2004, 64, 391–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project (2025) Jamovi (Version 2.6) [Computer Software]. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Mair, P.; Hatzinger, R. Extended Rasch Modeling: The ERm Package for the Application of IRT Models in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linacre, J.M. Item Discrimination and Infit Mean-Squares. Rasch Meas. Trans. 2000, 14, 743. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti, D.V. Guidelines, Criteria, and Rules of Thumb for Evaluating Normed and Standardized Assessment Instruments in Psychology. Psychol. Assess. 1994, 6, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, A.K.B.; Milek, J.; Joussen, A.M.; Dietrich-Ntoukas, T.; Lichtner, G. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Outcomes After Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty Versus Ultrathin Descemet Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 245, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torras-Sanvicens, J.; Blanco-Domínguez, I.; Sánchez-González, J.M.; Rachwani-Anil, R.; Spencer, J.F.; Sabater-Cruz, N.; Peraza-Nieves, J.; Rocha-De-lossada, C. Visual Quality and Subjective Satisfaction in Ultrathin Descemet Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty (UT-DSAEK) versus Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty (DMEK): A Fellow-Eye Comparison. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundlach, E.; Pilger, D.; Brockmann, T.; Dietrich-Ntoukas, T.; Joussen, A.M.; Torun, N.; Maier, A.K.B. Recovery of Contrast Sensitivity after Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty. Cornea 2021, 40, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellert, A.; Unterlauft, J.D.; Rehak, M.; Girbardt, C. Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty (DMEK) Improves Vision-Related Quality of Life. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 260, 3639–3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| FECD | DMEK | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Mild-to-Moderate | Advanced | Unilateral | Bilateral | |

| Modified Krachmer grade | 0 | 1–4 | 5–6 | - | - |

| Participants (n) | 20 | 18 | 15 | 9 | 12 |

| Age (mean ± SD, years) | 66.7 ± 10.8 | 63.6 ± 8.9 | 66.4 ± 10.2 | 69.7 ± 7.5 | 69.4 ± 7.5 |

| Men (%)–Women (%) | 10 (50%):10 (50%) | 4 (22%):14 (78%) | 11 (73%):4 (27%) | 6 (67%):3 (33%) | 5 (42%):7 (58%) |

| BCVA (mean ± SD, logMAR) | 0.029 ± 0.050 | 0.056 ± 0.129 | 0.086 ± 0.112 | 0.043 ± 0.045 | 0.024 ± 0.038 |

| CCT (mean ± SD, µm) | 545 ± 14 | 550 ± 19 | 582 ± 35 | 548 ± 18 | 533 ± 23 |

| Infit | Outfit | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.E. | Mean Squares | Mean Squares | |

| Visual Acuity Factor | ||||

| Q6. * Nel complesso, diventa sempre più difficile vedere i dettagli più fini, ad esempio le foglie sugli alberi. [Overall, fine details are becoming harder to see, for example, leaves on trees.] | 2.57 | 0.222 | 1.141 | 1.373 |

| Q7. * Nell’ultimo mese, la mia vista ha interferito con le mie attività quotidiane. [During the past month, my vision interfered with my daily activities.] | 2.48 | 0.191 | 1.244 | 1.124 |

| Q8. ** Leggere un comune testo stampato su carta? [Reading ordinary print on paper?] | 2.48 | 0.218 | 0.991 | 0.805 |

| Q9. ** Leggere un testo su uno schermo? [Reading text on a screen?] | 1.75 | 0.242 | 0.996 | 0.814 |

| Q10. ** Svolgere lavori o hobby che richiedono una buona visione da vicino? [Doing work or hobbies that require you to see well up close?] | 2.07 | 0.207 | 0.659 | 0.841 |

| Q11. ** Leggere il testo sui contenitori dei medicinali e foglietti illustrativi? [Reading text on medicine bottles and package inserts?] | 2.37 | 0.188 | 1.051 | 0.953 |

| Q12. ** Vedere i prezzi dei prodotti quando fai spese? [Seeing the prices of items when shopping?] | 1.75 | 0.242 | 0.855 | 0.688 |

| Glare factor | ||||

| Q1. * Nell’ultimo mese, ho notato dei cambiamenti della mia vista nel corso della giornata. [During the past month, my eyesight changed over the course of the day.] | 1.88 | 0.199 | 0.811 | 0.614 |

| Q2. * Nell’ultimo mese, ho avuto una visione annebbiata, peggiore al mattino. [During the past month, I have had blurred vision that is worst in the morning.] | 2.22 | 0.209 | 0.798 | 0.793 |

| Q3. * Nell’ultimo mese ho avuto difficoltà a mettere a fuoco, peggiore al mattino. [During the past month, I have had trouble with focusing that is worst in the morning.] | 1.92 | 0.201 | 0.851 | 0.698 |

| Q4. * Di notte, le luci brillanti sembrano circondate di raggi luminosi. [At night, bright lights look like a starburst] | 2.16 | 0.181 | 1.336 | 1.238 |

| Q5. * Di notte, attorno alle luci appare un cerchio luminoso (alone), ad esempio attorno ai lampioni delle strade. [At night, a bright circle (halo) appears to surround lights, such as street lights.] | 2.39 | 0.187 | 1.273 | 1.295 |

| Q13. ** Vedere ciò che hai di fronte quando entri da una zona illuminata dal sole in un’area in ombra, come ad esempio entrando in un parcheggio sotterraneo? [Seeing what is ahead of you when you enter from daylight into a shady area, such as entering into a parking ramp?] | 1.50 | 0.191 | 0.960 | 1.025 |

| Q14. ** Vedere ciò che hai di fronte di notte quando un’auto in arrivo ha i fari accesi? [Seeing what is ahead of you when an oncoming car has headlights on at night?] | 1.67 | 0.170 | 0.805 | 0.931 |

| Q15. ** Vedere ciò che hai di fronte quando il sole è basso all’alba o al tramonto? [Seeing what is ahead of you when the sun is low during sunrise or sunset?] | 2.22 | 0.182 | 1.262 | 1.158 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buzzi, M.; Carnicci, A.; Maccari, M.; Magherini, S.; Patel, S.V.; Virgili, G.; Giansanti, F.; Mencucci, R. Validation of the Italian Version of the Visual Function and Corneal Health Status (V-FUCHS) Questionnaire: A Patient-Reported Visual Disability Instrument for Fuchs’ Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113996

Buzzi M, Carnicci A, Maccari M, Magherini S, Patel SV, Virgili G, Giansanti F, Mencucci R. Validation of the Italian Version of the Visual Function and Corneal Health Status (V-FUCHS) Questionnaire: A Patient-Reported Visual Disability Instrument for Fuchs’ Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(11):3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113996

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuzzi, Matilde, Alberto Carnicci, Martina Maccari, Silvia Magherini, Sanjay V. Patel, Gianni Virgili, Fabrizio Giansanti, and Rita Mencucci. 2025. "Validation of the Italian Version of the Visual Function and Corneal Health Status (V-FUCHS) Questionnaire: A Patient-Reported Visual Disability Instrument for Fuchs’ Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 11: 3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113996

APA StyleBuzzi, M., Carnicci, A., Maccari, M., Magherini, S., Patel, S. V., Virgili, G., Giansanti, F., & Mencucci, R. (2025). Validation of the Italian Version of the Visual Function and Corneal Health Status (V-FUCHS) Questionnaire: A Patient-Reported Visual Disability Instrument for Fuchs’ Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(11), 3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113996