Vitamin C as an Adjuvant Analgesic Therapy in Postoperative Pain Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

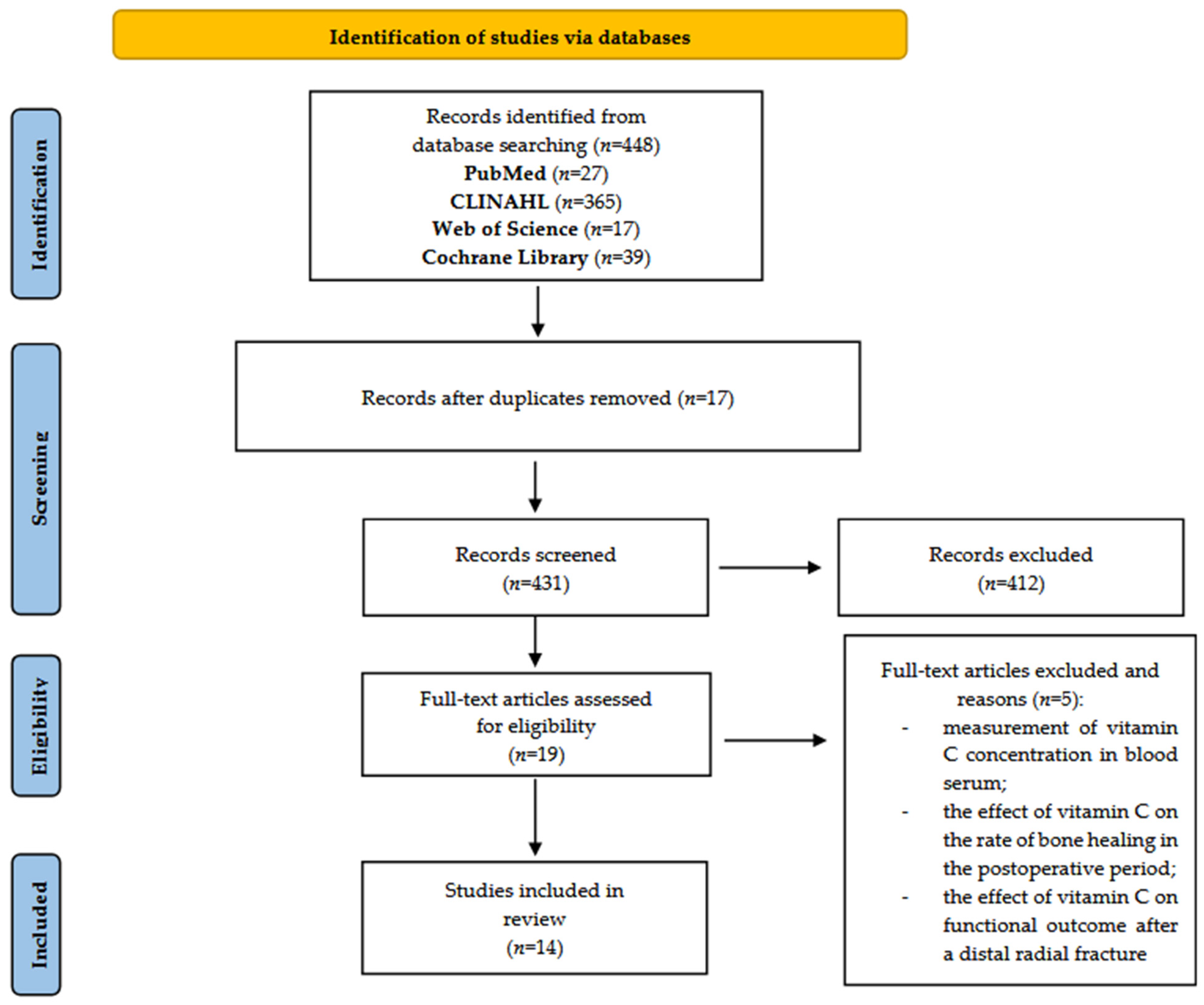

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Review Questions

- Does vitamin C administration in surgical patients reduce postoperative pain intensity?

- Does vitamin C administration in surgical patients reduce postoperative analgesic consumption?

- What doses of vitamin C are effective at reducing the need for analgesics?

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

- The first author’s name;

- The year of publication;

- The study design;

- The number of patients;

- The types of surgical procedures;

- The vitamin C dosage and route of administration;

- The timing of administration;

- The main study outcomes.

2.6. Data Synthesis

2.7. Assessment of Quality of the Included Studies

3. Results

3.1. Vitamin C and Reduction in Postoperative Pain Intensity

3.2. Vitamin C and Reduced Analgesic Consumption Postoperatively

3.3. Vitamin C Formulation and Dosage

4. Discussion

- ▪

- Antioxidant activity: Vitamin C, a potent antioxidant, neutralizes free radicals that cause oxidative stress and tissue damage. Postoperative pain frequently involves inflammation and oxidative stress at the surgical site. By reducing oxidative stress, vitamin C may mitigate pain through minimizing tissue damage and inflammation [4].

- ▪

- Inflammation modulation: Inflammatory processes significantly contribute to the development and continuation of pain following surgery. Vitamin C helps lower pro-inflammatory markers like IL-6, which trigger the release of acute-phase proteins. By influencing the body’s inflammatory response, vitamin C may ease discomfort and support tissue recovery [7].

- ▪

- Support for connective tissue and healing: As a vital factor in collagen production, vitamin C strengthens tissue structure. Enhanced collagen formation can relieve nerve compression, thereby reducing discomfort. Faster and more effective tissue regeneration may also aid in pain control and speed up healing [4].

- ▪

- Nerve protection: Vitamin C plays a role in preserving neural function. Nerve-related pain, including discomfort due to compression or irritation, often occurs after surgery. Thanks to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory roles, vitamin C may help shield nerves and limit pain transmission [7].

- ▪

- Neurotransmitter regulation: Vitamin C contributes to the production of catecholamine-based neurotransmitters. It is a required cofactor for dopamine β-hydroxylase, which transforms dopamine into norepinephrine, and may also enhance the dopamine output by maintaining tetrahydrobiopterin levels—an essential element for tyrosine hydroxylase activity. A similar mechanism supports serotonin synthesis. Medications that increase serotonin and norepinephrine levels are known to relieve pain [5].

- ▪

- Novel analgesic mechanism involving vitamin C as a cofactor in the biosynthesis of amidated opioid peptides: Vitamin C serves as a cofactor for peptidylglycine α-amidating monooxygenase (PAM), which converts the terminal ends of peptide chains into their active amidated forms. Several of these amidated neuropeptides act on opioid receptors. For instance, endomorphin 1 and 2 and amidated tetrapeptides display an exceptional selectivity and affinity for the μ-opioid receptor. Interestingly, tissues involved in neurotransmitter and peptide hormone synthesis have particularly high concentrations of vitamin C [6].

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hung, K.-C.; Lin, Y.-T.; Chen, K.-H.; Wang, L.-K.; Chen, J.-Y.; Chang, Y.-J.; Wu, S.-C.; Chiang, M.-H.; Sun, C.-K. The Effect of Perioperative Vitamin C on Postoperative Analgesic Consumption: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbari, F.; Alimohammadi, E. Unveiling the potential impact of vitamin C in postoperative spinal pain. Chin. Neurosurg. J. 2024, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitanya, N.C.; Muthukrishnan, A.; Krishnaprasad, C.M.S.; Sanjuprasanna, G.; Pillay, P.; Mounika, B. An Insight and Update on the Analgesic Properties of Vitamin C. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2018, 10, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likar, R.; Poglitsch, R.; Bejvančický, Š.; Carl, L.; Ferencik, M.; Klein-Watrycz, A.; Rieger, M.; Flores, K.S.; Schumich, A.; Vlamaki, Z.; et al. The Use of High-Dose Intravenous l-Ascorbate in Pain Therapy: Current Evidence from the Literature. Pain Ther. 2024, 13, 767–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, L.A.; González, J.F.C. Applications of vitamin C for pain management: Neurological action mechanisms and pharmacological aspects. Neurol. Perspect. 2022, 2, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.C.; McCall, C. The role of vitamin C in the treatment of pain: New insights. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doseděl, M.; Jirkovský, E.; Macáková, K.; Krčmová, L.K.; Javorská, L.; Paunová, J.; Marcolini, L.; Remião, F.; Nováková, L.; Mladenka, P.; et al. Vitamin C—Sources, Physiological Role, Kinetics, Deficiency, Use, Toxicity, And Determination. Nutrients 2021, 13, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett-Page, E.; Thomas, J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2009, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Tufanaru, C.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; Mu, P. Conducting systematic reviews of association (etiology): The Joanna Briggs Institute’s approach. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayatollahi, V.; Dehghanpour Farashah, S.; Behdad, S.; Vaziribozorg, S.; Rabbani Anari, M. Effect of intravenous vitamin C on postoperative pain in uvulopalatopharyngoplasty with tonsillectomy. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2017, 42, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.A.; Singh, R.B.; Singh, A. Vitamin C premedication reduces postoperative rescue analgesic requirement after laparoscopic surgeries. J. Anesth. Crit. Care Open Access 2016, 5, 216–219. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, Y.; Park, J.S.; Moon, S.; Yeo, J. Effect of Intravenous High Dose Vitamin C on Postoperative Pain and Morphine Use after Laparoscopic Colectomy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain Res. Manag. 2016, 2016, 9147279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.W.; Yang, H.S.; Yeom, J.S.; Ahn, M.W. The Efficacy of Vitamin C on Postoperative Outcomes after Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2017, 9, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarahzadeh, M.H.; Bioki, M.H.M.; Abbasi, H.; Jafari, M.A.; Sheikhpour, E. The Efficacy Of Vitamin C Infusion In Reducing Post-Intubation Sore Throat. Med. J. 2019, 53, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.K.; Dar, M.Y.; Kumar, S.; Yadav, A.; Kearns, S.R. Role of anti-oxidant (vitamin-C) in post-operative pain relief in foot and ankle trauma surgery: A prospective randomized trial. Foot Ankle Surg. 2019, 25, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Lim, S.H.; Cho, K.; Kim, M.; Lee, W.; Cho, Y.H. The efficacy of vitamin C on postlaparoscopic shoulder pain: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Anesth. Pain Med. 2019, 14, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Lim, S.; Yun, J.; Lee, W.; Kim, M.; Cho, K.; Ki, S. Additional effect of magnesium sulfate and vitamin C in laparoscopic gynecologic surgery for postoperative pain management: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Anesth. Pain Med. 2020, 15, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trankle, C.R.; Puckett, L.; Swift-Scanlan, T.; DeWilde, C.; Priday, A.; Sculthorpe, R.; Ellenbogen, K.A.; Fowler, A.; Koneru, J.N. Vitamin C Intravenous Treatment In the Setting of Atrial Fibrillation Ablation: Results From the Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled CITRIS-AF Pilot Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e014213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunay, D.L.; Ilgınel, M.T.; Ünlügenç, H.; Tunay, M.; Karacaer, F.; Biricik, E. Comparison of the effects of preoperative melatonin or vitamin C administration on postoperative analgesia. Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2020, 20, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelela, M.; Abedelkhalek, M.; Mamoun, M. Role of vitamin C in multimodal analgesia for sleeve gastrectomy: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Anaesth. Pain Intensive Care 2023, 27, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Gan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Sun, S.; Kang, P. Effect of perioperative single dose intravenous vitamin C on pain after total hip arthroplasty. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2024, 19, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bala, R.; Saini, R.M.; Kiran, S.; Bansal, P.; Kshetrapal, K.; Kataria, P. The effectiveness of Vitamin C for postoperative pain reliefin patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A prospective randomized double-blind trial. Indian J. Pain 2024, 38, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivro, M.; Omerović, Đ.; Lazović, F.; Papović, A. The effect of intravenous vitamin C administration on postoperative pain and intraoperative blood loss in older patients after intramedullary nailing of trochanteric fractures. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2024, 16, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielewicz, J.; Daniluk, B.; Kamieniak, P. VAS and NRS, Same or Different? Are Visual Analog Scale Values and Numerical Rating Scale Equally Viable Tools for Assessing Patients after Microdiscectomy? Pain Res. Manag. 2022, 2022, 5337483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelkarøy, M.T.; Benth, J.Š.; Simonsen, T.B.; Siddiqui, T.G.; Cheng, S.; Kristoffersen, E.S.; Lundqvist, C. Measuring pain intensity in older adults. Can the visual analogue scale and the numeric rating scale be used interchangeably? Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2024, 130, 110925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanazi, G.E.; El-Khatib, M.F.; Yazbeck-Karam, V.G.; Hanna, J.E.; Masri, B.; Aouad, M.T. Effect of vitamin C on morphine use after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A randomized controlled trial. Can. J. Anesth. J. Can. Anesth. 2012, 59, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albazaz, R.; Wong, Y.T.; Homer-Vanniasinkam, S. Complex regional pain syndrome: A review. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2008, 22, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzen, M.; Zengin, M.; Ciftci, B.; Uckan, S. Does the vitamin C level affect postoperative analgesia in patients who undergo orthognathic surgery? Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 52, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, M.; Bollen Pinto, B.; Belletti, A.; Putzu, A. Efficacy and safety of perioperative vitamin C in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Br. J. Anaesth. 2022, 128, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanase, F.; Fujii, T.; Naorungroj, T.; Belletti, A.; Luethi, N.; Carr, A.C.; Young, P.J.; Bellomo, R. Harm of IV High-Dose Vitamin C Therapy in Adult Patients: A Scoping Review. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 48, e620–e628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.X.; Tao, J.; Zhang, N.; Wang, J.Z. Neuroprotective properties of vitamin C on equipotent anesthetic concentrations of desflurane, isoflurane, or sevoflurane in high fat diet fed neonatal mice. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 10444–10458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Feng, L.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L.; Song, J.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, W.; Feng, Z. Intraoperative Vitamin C Reduces the Dosage of Propofol in Patients Undergoing Total Knee Replacement. J. Pain Res. 2021, 14, 2201–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. Notification Regarding Ascorbic Acid Injection. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/unapproved-drugs/fda-notification-regarding-ascorbic-acid-injection (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Ascorbic Acid; Wolters Kluwer Clinical Drug Information, Inc.: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2025.

- Industry Offers Insight Into Vitamin C Supply Chain. Available online: https://www.nutraingredients-usa.com/Article/2020/04/02/Industry-offers-insight-into-vitamin-C-supply-chain/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Vitamin C Will Soon Stop Being a Medicine in India. Available online: https://theprint.in/india/governance/vitamin-c-will-soon-stop-being-a-medicine-in-india/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population (P) | Surgical patient Patient ≥ 18 years old | Not a-surgical patient Patient < 18 years old |

| Intervention (I) | Vitamin C | - |

| Comparison (C) |

| - |

| Outcome (O) | Pain level/opioid dose | - |

| Study Type (S) |

|

|

| Years Considered/Time Period | All evidence published in the last 10 years, period: 2014–2024 | Publications prior to 2013 |

| Language | English | Other languages |

| Databases | MEDLINE (PubMed), CINAHL, Cochrane Library | Other databases |

| Keywords | “pain”, “acute pain”, “postoperative pain”, “vitamin C”, “ascorbic acid”, “pain level”, “pain relief”, “opioids dose” | n/a |

| Search Strategy | MEDLINE (PubMed): (“pain” OR “acute pain” OR “postoperative pain”) AND (“vitamin C” OR “ascorbic acid”) AND (“pain level” OR “pain relief” OR “opioids dose”) Limit: Language Results: 25 CINAHL: TX (“pain” OR “acute pain” OR “postoperative pain”) AND TX (“vitamin C” OR “ascorbic acid”) AND TX (“pain level” OR “pain relief” OR “opioids dose”) Limit: Language, years Results: 365 Web of Science: (“pain” OR “acute pain” OR “postoperative pain”) AND (“vitamin C” OR “ascorbic acid”) AND (“pain level” OR “pain relief” OR “opioids dose”) Limit: Years Results: 14 Cochrane Library: TX (“pain” OR “acute pain” OR “postoperative pain”) AND TX (“vitamin C” OR “ascorbic acid”) AND TX (“pain level” OR “pain relief” OR “opioids dose”) Limit: Years Results: 44 | n/a |

| First Author, Year | Study Design | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total Scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayatollahi V., et al. (2016) [11] | Arandomized double-blind clinical trial | *** | * | *** | 7 |

| Kumar A.A., et al. (2016) [12] | A prospective randomized double-blind study | *** | ** | *** | 8 |

| Jeon Y., et al. (2016) [13] | A randomized controlled trial | *** | * | ** | 8 |

| Lee G.W., et al. (2017) [14] | A prospectively randomized trial | *** | ** | ** | 7 |

| Jarahzadeh M.H., et al. (2019) [15] | A double-blind randomized study | **** | ** | *** | 8 |

| Jain S.K., et al. (2019) [16] | A prospective randomized trial | ** | ** | ** | 6 |

| Moon S., et al. (2019) [17] | A double-blind randomizedcontrolled trial | ** | ** | *** | 7 |

| Moon S., et al. (2020) [18] | A double-blindrandomized controlled trial | *** | ** | *** | 8 |

| Trankle C.A., et al. (2020) [19] | A prospective randomized double-blind study | ** | * | ** | 5 |

| Tunay D.L., et al. (2020) [20] | Arandomized double-blind clinical trial | *** | *** | *** | 8 |

| Aboelela M., et al. (2023) [21] | Arandomized double-blind clinical trial | ** | ** | *** | 7 |

| Han G., et al. (2024) [22] | A prospective randomized double-blind trial | *** | ** | *** | 8 |

| Bala R., et al. (2024) [23] | A prospective randomized double-blind trial | ** | ** | *** | 7 |

| Sivro M., et al. (2024) [24] | A prospective, single-blind, controlled, randomized clinical trial | ** | ** | *** | 7 |

| Author, Year | Country | Study Design | Number of Patients (n) | Surgical Procedures | Dosage and Route | Time of Administration | Pain Level | Results | Opioid Dose/Non-Opioid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayatollahi V., et al. (2016) [11] | Iran | A randomized double-blind clinical trial | 40 | Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) with tonsillectomy | An amount of 3 g of vitamin C in 500 mL of Ringer or 6 mL of normal saline in 500 mL of Ringer. | During the first 30 min after the beginning of the surgery. | The VAS scores at 6, 12, and 24 h after surgery were lower in the group receiving vitamin C than in the placebo group. | This research found that giving 3 g of intravenous vitamin C during surgery lessened pain after the procedure without raising adverse effects in patients undergoing surgery (UPPP and tonsillectomy). | Only IV paracetamol or pethidine. |

| Kumar A.A., et al. (2016) [12] | The Indies | A prospective randomized double-blind study | 200 | Laparoscopic surgeries | Group 1 received oral vitamin C (2 g) and group 2 patients received a placebo. | In the night and 2 h before surgery. | The VAS score in patients from group 1 receiving vitamin C immediately after surgery was 2.64 ± 1.13, compared to 3.72 ± 1.63 in group 2. At the 30th minute, the VAS score was 2.14 ± 0.51 in group 1, while it was 2.88 ± 1.07 in group 2. | We found that vitamin C use lessened immediate postoperative pain and decreased the need for fentanyl as a rescue pain reliever after surgery. | An injection of fentanyl, 25 micrograms IV, was given as rescue analgesic when the patient had a VAS score > 4. |

| Jeon Y., et al. (2016) [13] | Korea | A randomized controlled trial | 100 | Laparoscopic colectomy | Vitamin C, 50 mg/kg (ascorbic acid, 10 g/20 mL), mixed with 0.9% NaCl to reach a total volume of 50 mL; the participants in the placebo group were given normal saline alone. | The solution was infused over 30 min using an infusion pump. | The NRS pain scores during coughing and the NRS fatigue scores were similar across both groups at each measured time point. | This study demonstrates that a high-dose vitamin C infusion lowered pain within the first 24 h after surgery and reduced early postoperative morphine use. Further investigation is required to determine if increasing the dose and extending the infusion duration can enhance these outcomes. | All patients began patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) upon reaching the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU). The PCA delivered 1 mg of morphine boluses with a 5 min lockout and no continuous infusion. Patients were advised to press the PCA button whenever they felt pain. If the pain persisted above a VAS score of 4 for at least 30 min, a 50 mg tramadol injection was administered as additional relief. |

| Lee G.W., et al. (2017) [14] | Korea | A prospectively randomized trial | 123 | Posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) | Vitamin C in pills or placebo pills (no dose information). | Vitamin C therapy began on the first day after surgery and was given each morning for the next 45 days. | The clinical outcome was assessed using the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI). The intensity of lower back pain improved significantly in both groups relative to the pre-surgery pain levels; however, no notable differences emerged between the groups throughout the follow-up phase. | The pain intensity one year after surgery, the main outcome, did not differ significantly between the two groups. However, vitamin C might support better functional recovery following PLIF surgery, particularly within the initial 3 months after the operation. | No data. |

| Jarahzadeh M.H., et al. (2019) [15] | Iran | A double-blind randomized study | 70 | Laparoscopic surgery | An amount of 2 g of vitamin C mixed with 0.9% NaCl (500 mL) or only 500 mL of 0.9% NaCl. | A total of 30 min after induction of anesthesia injection. | The mean VAS scores (±standard deviations) at 1 h were 2.09 ± 2.44 and 3.54 ± 2.44 (p = 0.011); at 6 h, they were 1.66 ± 1.84 and 3.34 ± 2.04 (p = 0.001); and at 24 h, they were 1.11 ± 0.57 and 1.61 ± 1.6 (p = 0.001) for the experimental and control groups, respectively. | The use of vitamin C reduced the incidence of a sore throat and the pain score. Vitamin C appears to reduce the need for morphine to manage postoperative pain. | A total of 5 mg of morphine after the induction of anesthesia. |

| Jain S.K., et al. (2019) [16] | The Indies | A prospective randomized trial | 60 | Patients with isolated foot and ankle trauma | Patients with isolated foot and ankle trauma who underwent surgery were randomly allocated to receive either 500 mg of vitamin C or a placebo tablet, taken twice daily. | All patients additionally received 75 mg of diclofenac sodium twice daily for five days to manage acute pain and reduce inflammation, and later as needed. | The group that received vitamin C showed improvement in the VAS scores at the end of the second and sixth weeks of follow up, reduced analgesia requirements, and an improved functional outcome compared to the placebo group. | This study shows that the supplementation of vitamin C in patients undergoing surgery for foot and ankle trauma helped to reduce the analgesic requirements, improve the VAS scores, and achieve better functional outcomes. | No data. |

| Moon S., et al. (2019) [17] | Korea | A double-blind randomized controlled trial | 60 | Elective laparoscopic hysterectomy | An amount of 500 mg of vitamin C mixed with 0.9% NaCl (500 mL) or only 500 mL of 0.9% NaCl. | Twice a day from 7 a.m. and 7 p.m. on the day of surgery to the third day after surgery. | The NRS score of PLSP showed a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001), particularly 24 h after the operation (p = 0.002). | The total fentanyl use after surgery was notably lower in group C at both 24 and 48 h post-operation (p = 0.002 and p = 0.012, respectively). Group C also reported a significantly reduced PLSP intensity at 24 h (p = 0.002). Moreover, the occurrence of PLSP was considerably less in group C at both time points (p = 0.002 and p = 0.035, respectively). | Following surgery, a PCA device was attached to the IV line, and patients were moved to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU). The PCA solution included 10 μg/mL of fentanyl in saline, delivering 1 mL bolus doses with a 5 min lockout period and no continuous background infusion. |

| Moon S., et al. (2020) [18] | Korea | A double-blind randomized controlled trial | 132 | Laparoscopic gynecology operation | There were 4 groups: Group M: magnesium sulfate, 40 mg/kg; Group V: vitamin C, 50 mg/kg; Group MV: magnesium sulfate + vitamin C—magnesium sulfate, 40 mg/kg, and vitamin C, 50 mg/kg; Group C: control group —0.9% NaCl, 40 mL. | No data. | The pain scores at rest after surgery were significantly lower in group MV at 1, 6, 24, and 48 h (4\[3, 4]; 3\[2, 3]; 2\[1, 2]; and 1.5\[1, 2], respectively) compared to those of group C (5\[4, 6]; 3\[3, 5]; 3\[2, 5]; and 3\[1.75, 4], with p-values of 0.001, 0.001, <0.001, and 0.002). At the 1 h mark, group V also showed significantly lower scores (4\[3, 4]) than group C (5\[4, 6]; p = 0.006). Moreover, group MV had markedly lower NRS scores than both group M and group V at 24 h post-surgery (p < 0.001 and p = 0.002, respectively). No significant differences in pain scores were observed between group M and group V. | The combined use of magnesium sulfate and vitamin C offers added value in managing postoperative pain following laparoscopic gynecologic procedures when compared to the use of either magnesium sulfate or vitamin C alone. | The PCA mixture consisted of 15 μg/mL of fentanyl in saline, set to deliver 1 mL bolus doses with a 5 min lockout and no continuous infusion. Following surgery, the PCA device was attached to the IV line, and patients were moved to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU). If additional pain relief was needed, 30 mg of ketorolac was given upon request. |

| Trankle C.A., et al. (2020) [19] | USA | A prospective randomized double-blind study | 20 | Catheter ablation (treatment for atrial fibrillation (AF) | Intravenous vitamin C (50 mg/kg administered) or matched placebo. | Administered every 6 h for a total of four doses, starting with one given prior to the ablation procedure. | No data (only level/changes in CRP, IL-6, and ascorbate). | High-dose ascorbic acid is safe and generally well tolerated during AF ablation and may help reduce the increase in C-reactive protein, though no consistent effects were observed on interleukin 6 levels. Additional research is required to confirm these results and assess its potential to improve meaningful clinical outcomes. | No data. |

| Tunay D.L., et al. (2020) [20] | Turkey | A randomized double-blind clinical trial | 165 | Elective major abdominal surgery | Group M (n = 55) was given 6 mg of melatonin (Melatonina 3 mg tablets), group C (n = 55) received 2 g of vitamin C (Solgar Vitamin C 1000 mg tablets), and group P (n = 55) was administered a placebo tablet, all taken orally in the preoperative area. | One hour before the surgery. | The postoperative VAS scores were notably reduced in both group M and group C compared to group P at all the measured intervals, with the exception of the first hour following surgery. | Patients in groups M and C needed fewer additional pain medications and had lower rates of nausea and vomiting than those in group P. In summary, taking 6 mg of melatonin or 2 g of vitamin C orally before surgery reduced pain levels, the overall morphine use, the need for extra analgesia, and the frequency of nausea and vomiting compared to a placebo. | At peritoneal closure, the patients received a loading dose of 0.1 mg/kg of IV morphine (Galen Co) and 75 mg of intramuscular diclofenac sodium (Voltaren, Novartis) for postoperative pain control. After extubation, they were transferred to the PACU and monitored for at least 60 min. A PCA device delivering morphine at 0.3 mg/mL was then connected to a vein, enabling patient-controlled analgesia. The PCA was set to deliver 0.2 mg/kg bolus doses with a 10 min lockout and no background infusion. If a patient reported pain with a VAS score above 4 and requested additional relief beyond PCA, 75 mg of IM diclofenac sodium was given as supplemental analgesia. |

| Aboelela M., et al. (2023) [21] | Egypt | A randomized double-blind clinical trial | 50 | Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy | Vitamin C, 500 mg, as an oral capsule, or a placebo. | Every 8 h for 5 days perioperatively (4 days preoperative, and the operative day). | The VAS score was lower in group C compared to group N at 4, 8, and 12 h after surgery. | Vitamin C’s antioxidant ability, pain-relieving effects, and NMDA-receptor-blocking activity make it suitable for inclusion in multimodal pain strategies. Vitamin C serves as a co-analgesic, enhances postoperative pain control, and lowers the reliance on additional analgesics. | Morphine IV, 0.05–0.10 mg/kg, if the VAS score was >4. |

| Han G., et al. (2024) [22] | China | A prospective randomized double-blind trial | 100 | THA (endoprosthetics) | During surgery, the vitamin C group was administered 3 g of vitamin C diluted in 500 mL of normal saline via IV, while the control group received a 3 g placebo solution. | A total of 24 h after surgery. | Although the resting and movement-related pain scores were lower and hip mobility was improved at 24 h post-surgery in the vitamin C group, no statistically significant differences were observed between the groups at that time point. Moreover, the overall reductions in morphine use and the VAS scores did not exceed the minimal clinically important thresholds (10 mg for morphine; 1.5 at rest; and 1.8 with movement on the VAS). | The main objective was to assess whether giving intravenous vitamin C around the time of total hip replacement would lower postoperative morphine consumption. While the intake over the first 24 h after surgery was evaluated, no significant differences were found between the two groups during the overall hospital stay. | During the perioperative period, the surgeon administered periarticular local infiltration analgesia. If the patient was unable to endure the pain, 10 mg of morphine hydrochloride was administered subcutaneously as rescue analgesia. |

| Bala R., et al. (2024) [23] | England | A prospective randomized double-blind trial | 60 | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | Group C (n = 30) was given 1 g of vitamin C (10 mL of 100 mg/mL Curevit) diluted with 40 mL of 0.9% NaCl to make 50 mL in total, while group N received 50 mL of saline alone. | If another dose was needed, it could be repeated after 8 h. As a third option, 50 mg of diclofenac was given intramuscularly, with a maximum dosing interval of once every 8 h. | On the NRS, a pain intensity > 4 was observed in group C immediately after surgery, as well as 4 and 24 h after the procedure. | A single intraoperative dose of vitamin C is a reasonable option in multimodal anesthesia for patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, as it alleviates postoperative pain, reduces the need for rescue analgesia, and is safe and well tolerated. | Intraoperative analgesia was supplemented by fentanyl, 1 μg/kg/h, and port-site infiltration with a local anesthetic. |

| Sivro M., et al. (2024) [24] | Bosnia and Herzegovina | A prospective, single-blind, controlled, randomized clinical trial | 60 | Trochanteric fracture treated with intramedullary nailing | The vitamin C group received 2 g of ascorbic acid in 500 mL of 0.9% NaCl intravenously 30 min before the incision, followed by 1 g in 500 mL of saline daily for two days after surgery. The control group was given 500 mL of 0.9% NaCl without vitamin C, following the same schedule. | The median postoperative consumption of metamizole was significantly higher in the control group than in the vitamin C group (p = 0.003). | The visual analog scale (VAS) scores were assessed at 24 and 48 h after surgery. The median scores were significantly greater in the control group compared to the vitamin C group at both time points (p = 0.001 and p < 0.0005, respectively). | The findings indicated a marked decrease in reported pain and the reduced use of analgesics among patients given intravenous vitamin C, supporting its potential role as an adjunctive analgesic in elderly individuals with hip fractures. | Metamizole was given intravenously for pain relief, with a maximum allowable dose of 5 g per day. |

| Vitamin C (p.o) | Vitamin C (IV) | Vitamin C + MgSO4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C blood concentration | Low | High | High |

| Pain relief effect | Minimal | Moderate | Stronge (synergism) |

| Opioid consumption | No/minimal reduction | Moderate reduction | Reduction |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W.; Lange, S.; Dąbrowski, S.; Długoborska, K.; Piotrkowska, R. Vitamin C as an Adjuvant Analgesic Therapy in Postoperative Pain Management. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3994. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113994

Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska W, Lange S, Dąbrowski S, Długoborska K, Piotrkowska R. Vitamin C as an Adjuvant Analgesic Therapy in Postoperative Pain Management. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(11):3994. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113994

Chicago/Turabian StyleMędrzycka-Dąbrowska, Wioletta, Sandra Lange, Sebastian Dąbrowski, Klaudia Długoborska, and Renata Piotrkowska. 2025. "Vitamin C as an Adjuvant Analgesic Therapy in Postoperative Pain Management" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 11: 3994. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113994

APA StyleMędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W., Lange, S., Dąbrowski, S., Długoborska, K., & Piotrkowska, R. (2025). Vitamin C as an Adjuvant Analgesic Therapy in Postoperative Pain Management. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(11), 3994. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113994