Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty in Patients with Os Acromiale: A Systematic Review of Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

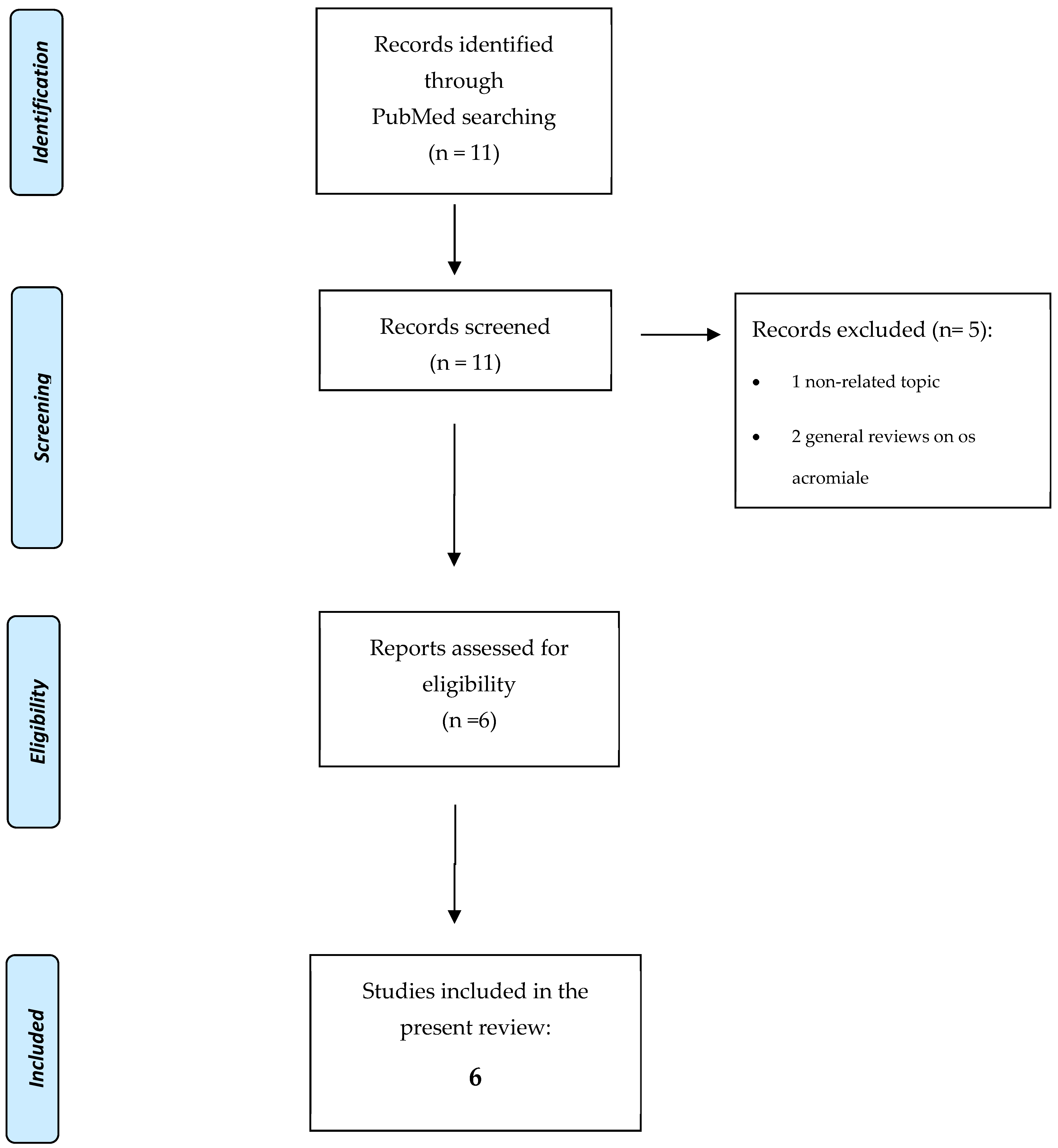

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Collection Process

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

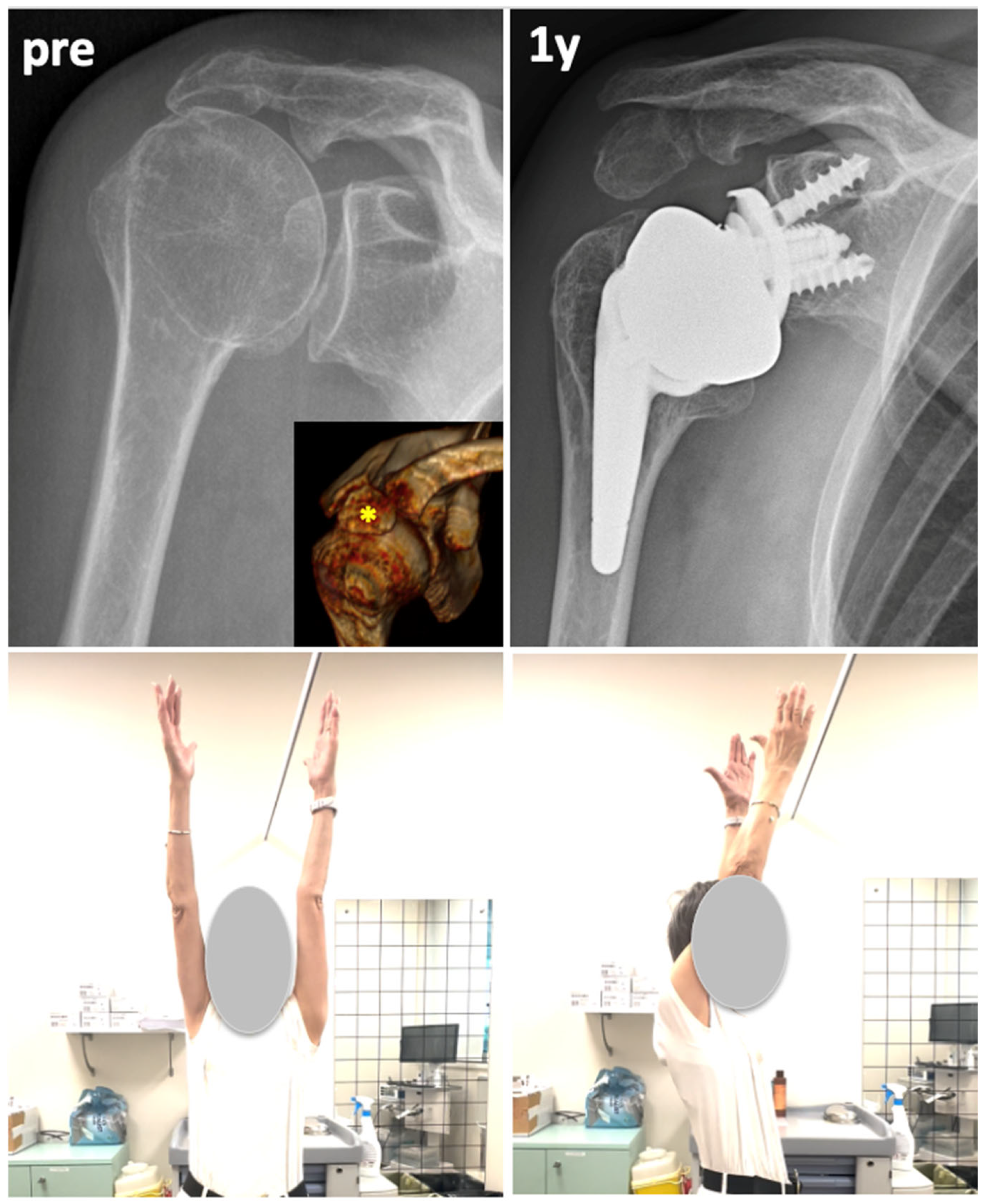

3.1. Qualitative Synthesis of Clinical and Radiological Results

3.2. Methodological Quality Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McClure, J.G.; Raney, R.B. Anomalies of the Scapula. Clin. Orthop. 1975, 110, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, C.A.; Humble, B.J.; Rodosky, M.W.; Sekiya, J.K. Symptomatic Os Acromiale. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2006, 14, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurst, S.A.; Gregory, T.M.; Reilly, P. Os acromiale: A review of its incidence, pathophysiology, and clinical management. EFORT Open Rev. 2019, 4, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yammine, K. The prevalence of os acromiale: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Anat. 2014, 27, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macalister, A. Notes on Acromion. J. Anat. Physiol. 1893, 27, 244.1–251. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, J.-H.; Kim, W.-Y.; Park, S.-E.; Kim, Y.-Y.; Moon, C.-Y. Operative Treatment of Symptomatic Os Acromiale. J. Korean Shoulder Elb. Soc. 2008, 11, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boileau, P.; Watkinson, D.J.; Hatzidakis, A.M.; Balg, F. Grammont reverse prosthesis: Design, rationale, and biomechanics. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2005, 14, S147–S161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammont, P.M.; Baulot, E. Delta Shoulder Prosthesis for Rotator Cuff Rupture. Orthopedics 1993, 16, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, C.D.; Brown, B.T.; Schmidt, C.C. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 2013, 44, 389–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walch, G.; Mottier, F.; Wall, B.; Boileau, P.; Molé, D.; Favard, L. Acromial insufficiency in reverse shoulder arthroplasties. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2009, 18, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpeggiani, G.; Hodel, S.; Götschi, T.; Kriechling, P.; Bösch, M.; Meyer, D.C.; Wieser, K. Os Acromiale in Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty: A Cohort Study. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2020, 8, 2325967120965131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.M.; Schmidt, C.M.; Kucharik, M.; Givens, J.; Christmas, K.N.; Simon, P.; Frankle, M.A. Do preoperative scapular fractures affect long-term outcomes after reverse shoulder arthroplasty? J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2024, 33, S74–S79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, C.I.; Talati, R.; White, C.M. A Clinician’s Perspective on Rating the Strength of Evidence in a Systematic Review. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2009, 29, 1017–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erşen, A.; Bayram, S.; Can Atalar, A.; Demirhan, M. Do we need to stabilize and treat the os acromiale when performing reverse shoulder arthroplasty? Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2019, 105, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, B.C.; Gulotta, L.V.; Dines, J.S.; Dines, D.M.; Warren, R.F.; Craig, E.V.; Taylor, S.A. Acromion Compromise Does Not Significantly Affect Clinical Outcomes after Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty: A Matched Case-Control Study. HSS J.® Musculoskelet. J. Hosp. Spec. Surg. 2019, 15, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aibinder, W.R.; Schoch, B.S.; Cofield, R.H.; Sperling, J.W.; Sánchez-Sotelo, J. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty in patients with os acromiale. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2017, 26, 1598–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boileau, P.; Watkinson, D.; Hatzidakis, A.M.; Hovorka, I. Neer Award 2005: The Grammont reverse shoulder prosthesis: Results in cuff tear arthritis, fracture sequelae, and revision arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2006, 15, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, B.; Nové-Josserand, L.; O’Connor, D.P.; Edwards, T.B.; Walch, G. Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty: A Review of Results According to Etiology. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2007, 89, 1476–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirveaux, F.; Favard, L.; Oudet, D.; Huquet, D.; Walch, G.; Mole, D. Grammont inverted total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis with massive rupture of the cuff: Results of a Multicentre Study of 80 Shoulders. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2004, 86-B, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumstein, M.A.; Pinedo, M.; Old, J.; Boileau, P. Problems, complications, reoperations, and revisions in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: A systematic review. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2011, 20, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lädermann, A.; Edwards, T.B.; Walch, G. Arm lengthening after reverse shoulder arthroplasty: A review. Int. Orthop. 2014, 38, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lädermann, A.; Denard, P.J.; Collin, P.; Zbinden, O.; Chiu, J.C.-H.; Boileau, P.; Olivier, F.; Walch, G. Effect of humeral stem and glenosphere designs on range of motion and muscle length in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Int. Orthop. 2020, 44, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutsiadis, A.; Lenoir, H.; Denard, P.J.; Panisset, J.-C.; Brossard, P.; Delsol, P.; Guichard, F.; Barth, J. The lateralization and distalization shoulder angles are important determinants of clinical outcomes in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2018, 27, 1226–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streit, J.J.; Shishani, Y.; Gobezie, R. Medialized Versus Lateralized Center of Rotation in Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty. Orthopedics 2015, 38, e1098–e1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauci, M.-O.; Chaoui, J.; Berhouet, J.; Jacquot, A.; Walch, G.; Boileau, P. Can surgeons optimize range of motion and reduce scapulohumeral impingements in reverse shoulder arthroplasty? A computational study. Shoulder Elb. 2022, 14, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publication | Comparative (LOE) | Preoperative Diagnosis | N^ Cases of RTSA + OS Acromiale (Total Cases If Mix Series) | Total RTSA Series with Same Indication (%) | Acromial Insufficiency Included | Os Acromiale Type (Pre/Meso/Meta) | Follow-Up (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walch et al. JSES 2009 [10] | Yes (III) | CTA, MCT, HA revision | 23 (41) | 457 (5%) | Yes | 23 meso | 40 (24–100) |

| Aibinder et al. JSES 2017 [16] | No (IV) | CTA, MCT | 25 | N/A; 1079 total RSA database | No | 3:20:2 | 31 (24–81) |

| Ersen et al. OT:SR 2019 [14] | Yes (III) | CTA | 10 | 46 (22%) | No | 10 meso | 60 (24–105) |

| Werner et al. HSSJ 2019 [15] | Yes (III) | CTA | N/A (11) | 124 (9%) | Yes * | N/A | 28 |

| Carpeggiani et al. OJSM 2020 [11] | Yes (III) | Mix | 45 reviewed; 52 os acromiale | 962 (5%) | No | 14:30:1 | 52 (12–121) |

| Davis et al. JSES 2024 [12] | Yes (III) | CTA, MCT, RA | 40 (72) | 525 (8%) | Yes | N/A | 76 ± 80 |

| TOTAL or weighted MEAN | - | - | 161 136 ^ | 3193 2114 ^^ (6.4%) | - | - | 52 months |

| Publication | Postoperative Complications | Postoperative Problems | Revision/Reoperation | Clinical Results | Vs RTSA | Radiological Acromial Tilt, n° Cases (5) | Acromial Tilt Influence on Outcome | Radiological Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walch et al. JSES 2009 [10] | N/A | N/A | No | CS 68 AF 141° | No differences | 24/38 (63%) * | No | - |

| Aibinder et al. JSES 2017 [16] | 2 dislocations | 1 painful OSa 3 unsatisfactory results (no further explanation) | 2 revisions 1 reoperation (OSa excision + deltoid advancement) | Pain 2.0 ASES 66 AF 124° ER1 46° IR L4 | N/A | 7/25 (28%) | No | Postoperative inferior acromial tilt = 32.3° (10–64) |

| Ersen et al. OT:SR 2019 [14] | No | No | No | Pain 1.2 CS 66.4 qDASH 22 AF 130° ER1 29° | No differences | N/A | No | AH distance = 19.3 (16–22) mm (significantly shorter than controls, 32.3 mm) |

| Werner et al. HSSJ 2019 [15] | No | No | No | ASES 69 SF-12 PCS 36.8 SF-12 MCS 54 Marx activity scale 6.5 | No differences | N/A | N/A | - |

| Carpeggiani et al. OJSM 2020 [11] | 2 glenoid loosening 2 spine fractures 1 not specified | 12 painful OSa | 3 revisions | Relative CS 70 SSV 70 AF 107° ER1 23° | Lower AF at 1 y (104° vs. 114°) and lower abduction at 2 y (103° vs. 121°) Slight negative trend after 2 y | 27/45 (60%) | No | - |

| Davis et al. JSES 2024 [12] | N/A | N/A | N/A | Pain 1.7 ASES 64 | No differences (excluding MF fracture) Lower ASES pain (33 vs. 39.2) at 1 y | N/A | N/A | - |

| TOTAL or weighted MEAN | 7/161 (4.3%) | - | 6 (3.7%) | - | - | 58/108 (54%) | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ranieri, R.; Schroeder, M.; Lacouture, J.D.; Tatangelo, C.; Delle Rose, G.; Conti, M.; Garofalo, R.; Castagna, A. Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty in Patients with Os Acromiale: A Systematic Review of Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3935. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113935

Ranieri R, Schroeder M, Lacouture JD, Tatangelo C, Delle Rose G, Conti M, Garofalo R, Castagna A. Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty in Patients with Os Acromiale: A Systematic Review of Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(11):3935. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113935

Chicago/Turabian StyleRanieri, Riccardo, Matthias Schroeder, Juan David Lacouture, Ciro Tatangelo, Giacomo Delle Rose, Marco Conti, Raffaele Garofalo, and Alessandro Castagna. 2025. "Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty in Patients with Os Acromiale: A Systematic Review of Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 11: 3935. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113935

APA StyleRanieri, R., Schroeder, M., Lacouture, J. D., Tatangelo, C., Delle Rose, G., Conti, M., Garofalo, R., & Castagna, A. (2025). Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty in Patients with Os Acromiale: A Systematic Review of Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(11), 3935. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113935