Retrospective Analysis of Laparoscopic Varicocelectomy in Pediatric Patients: Impact of Lymphatic-Sparing Techniques and Methylene Blue on Outcomes—A Series of Cases

Abstract

1. Introduction

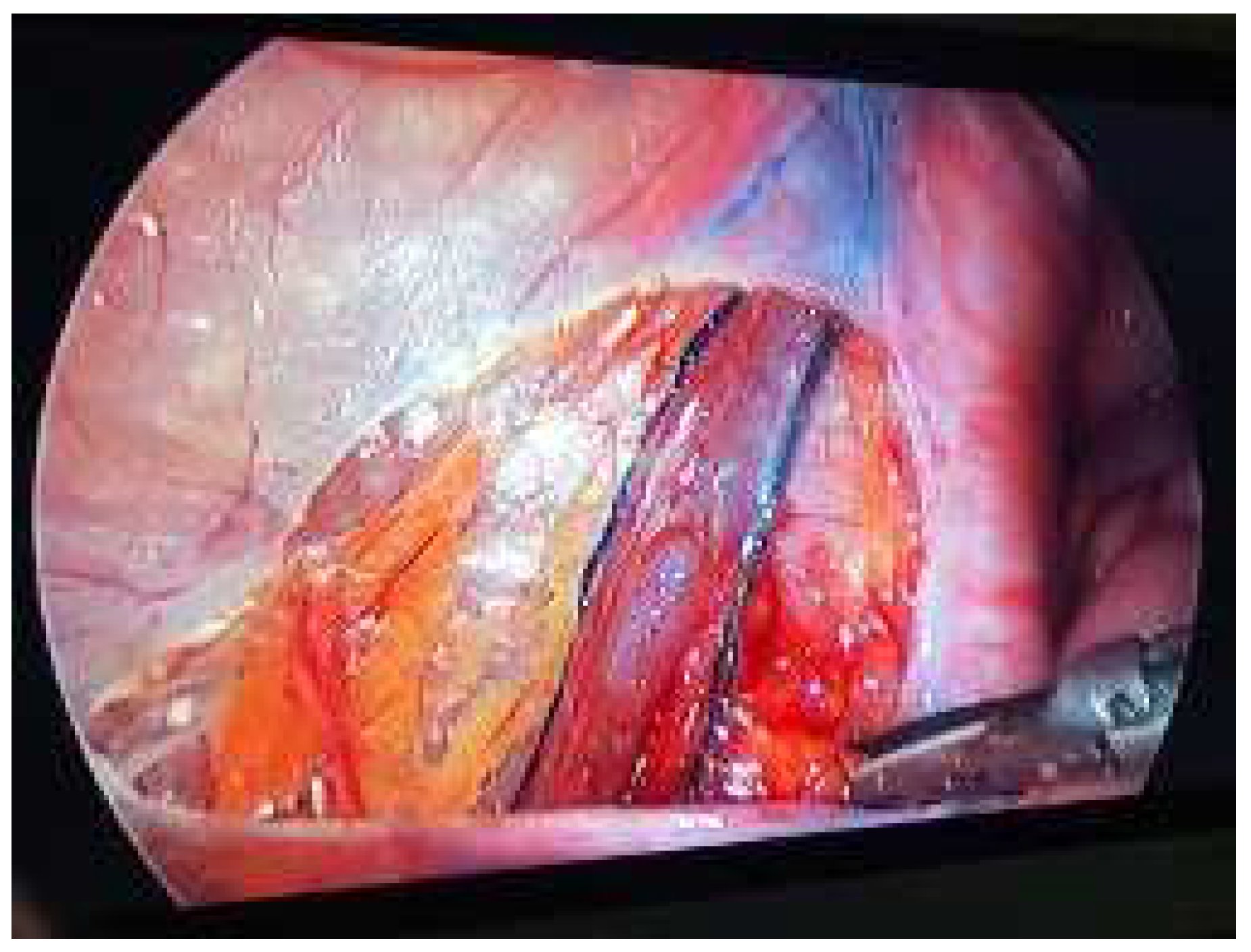

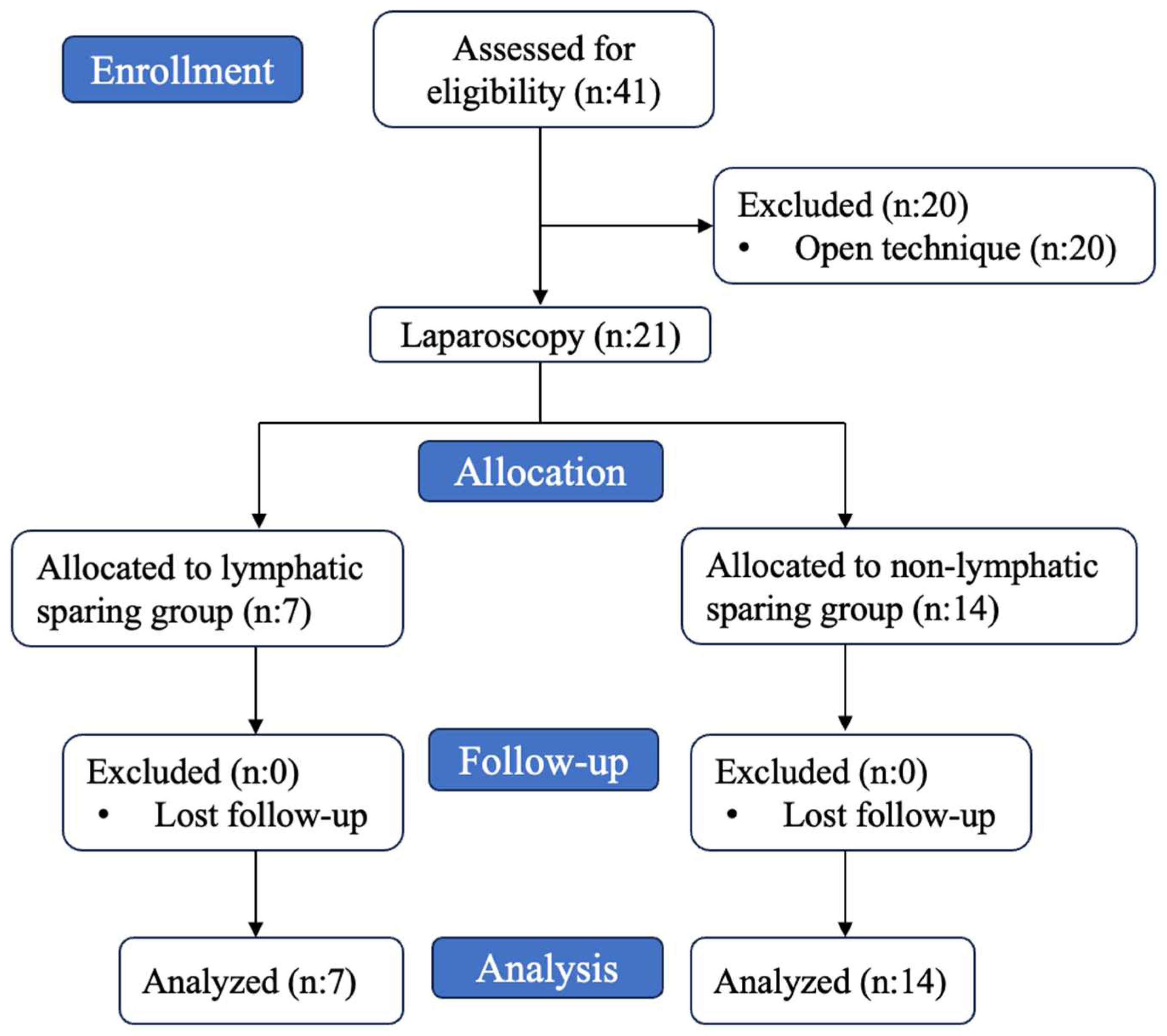

2. Materials and Methods

3. Statistical Analysis

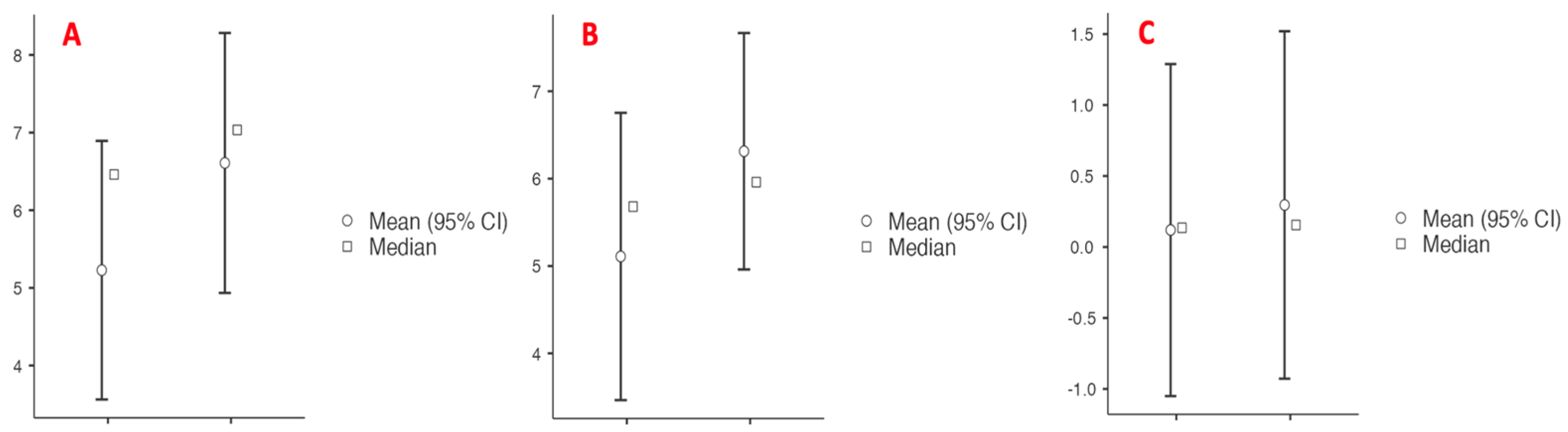

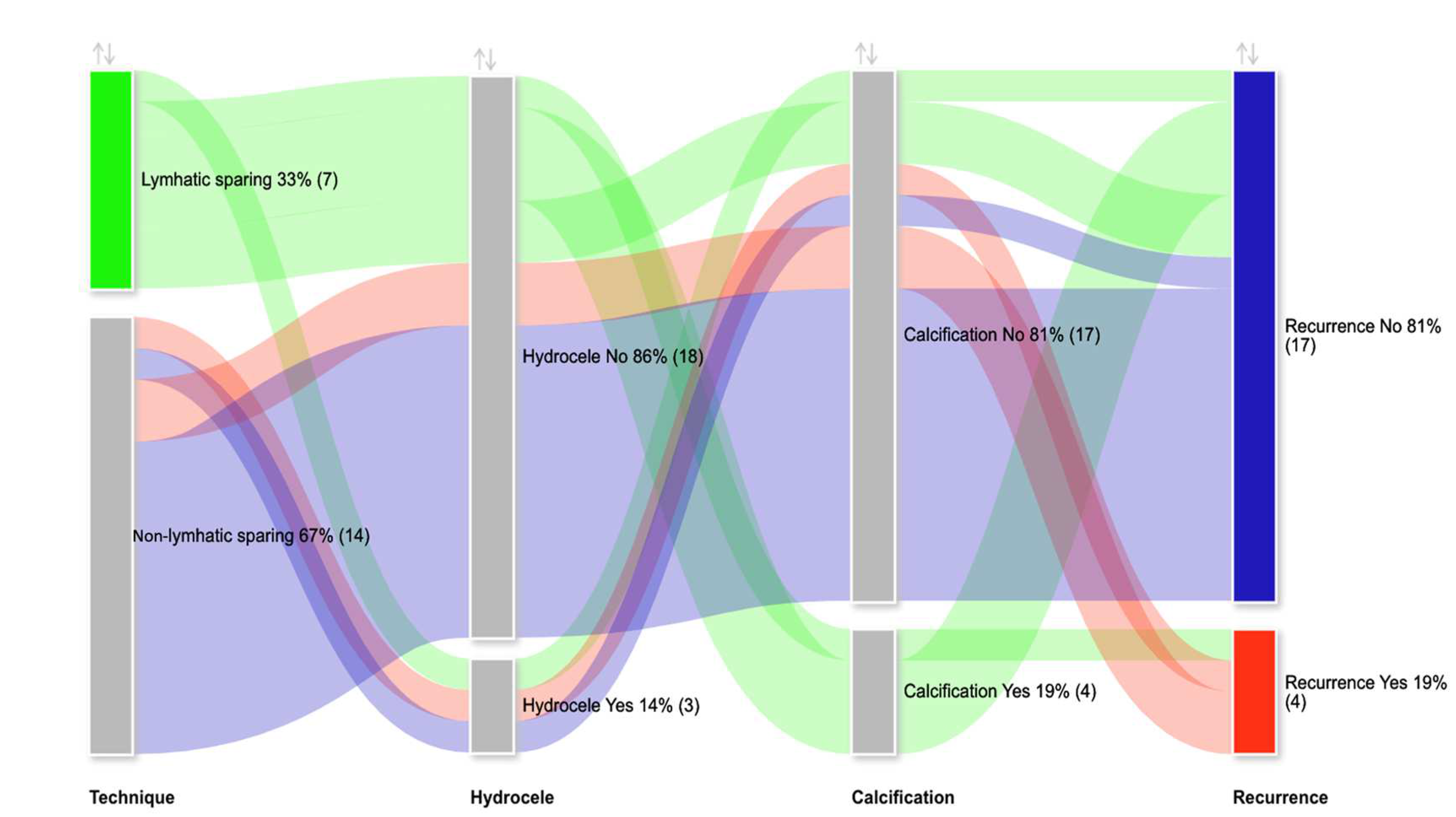

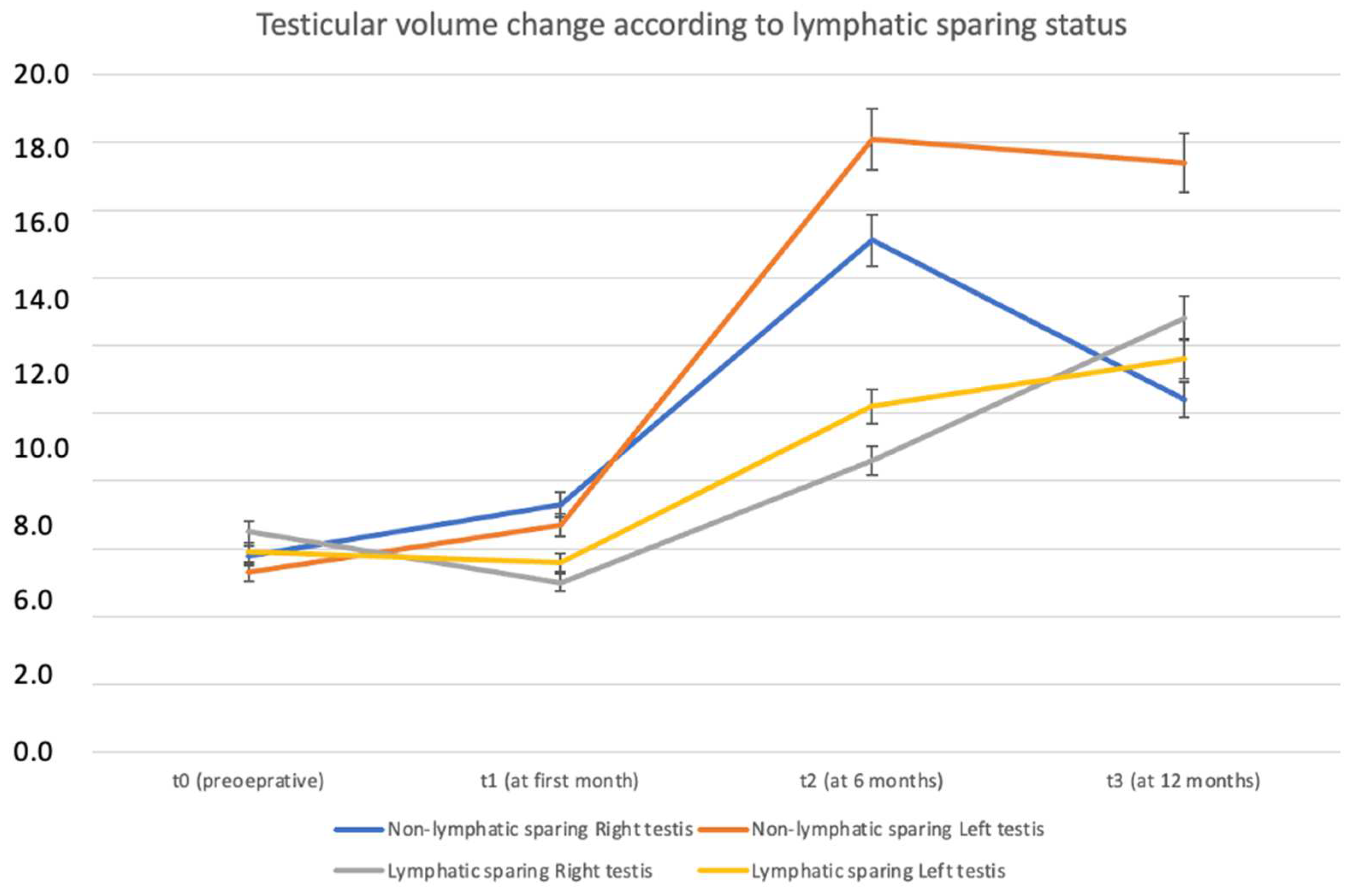

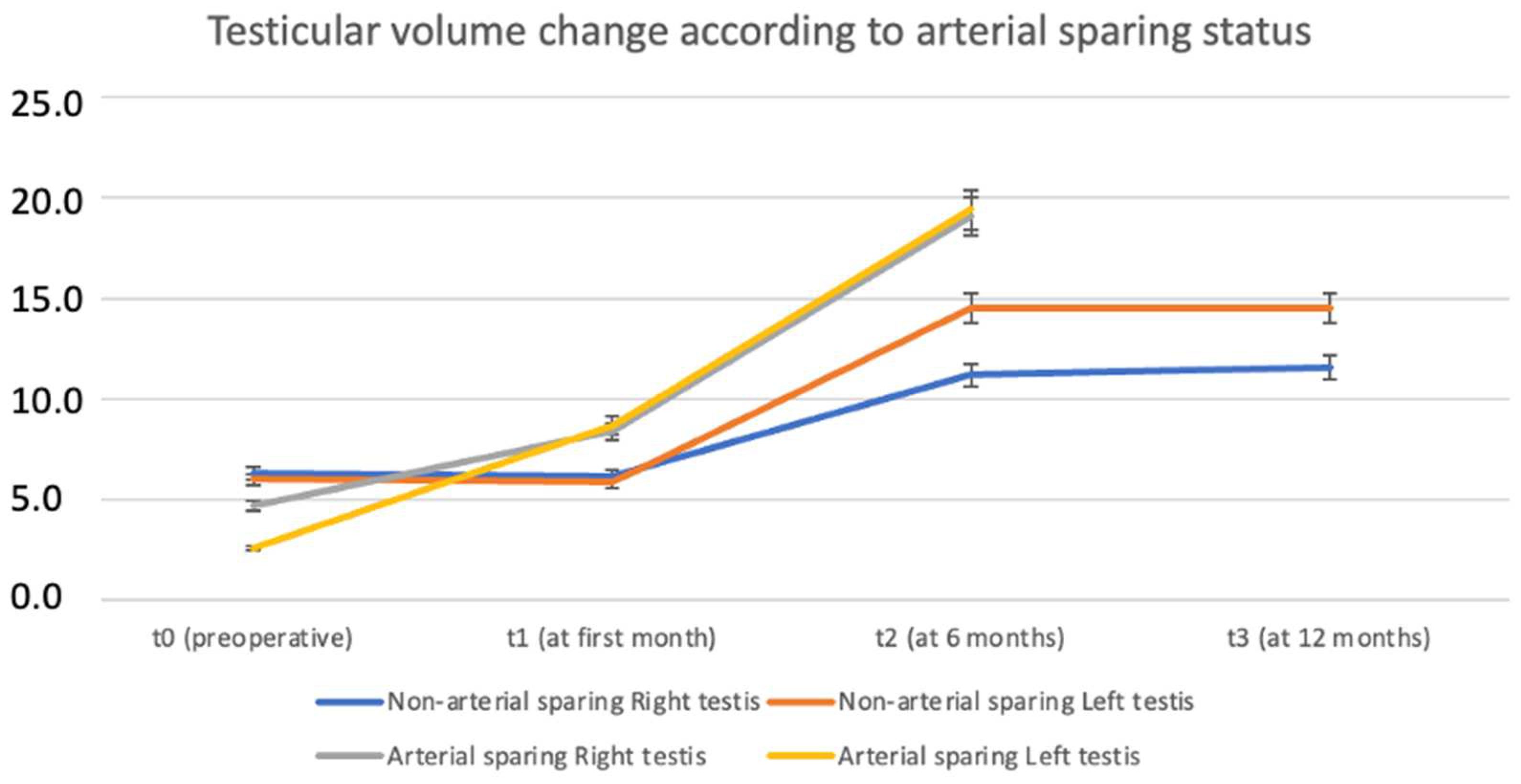

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tandon, S.; Bennett, D.; Mark Nataraja, R.; Pacilli, M. Outcome following the surgical management of varicocele in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther. Adv. Urol. 2023, 15, 17562872231206239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Akbay, E.; Cayan, S.; Doruk, E.; Duce, M.N.; Bozlu, M. The prevalence of varicocele and varicocele-related testicular atrophy in Turkish children and adolescents. BJU Int. 2000, 86, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radmayr, C.; Bogaert, G.; Burgu, B.; Castagnetti, M.S.; Dogan, H.S.; O’Kelly, F.; Quaedackers, J.; Rawashdeh, Y.F.H.; Silay, M.S.; Hoen, L.A.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Paediatric Urology; European Association of Urology: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Riccabona, M.; Oswald, J.; Koen, M.; Lusuardi, L.; Radmayr, C.; Bartsch, G. Optimizing the operative treatment of boys with varicocele: Sequential comparison of 4 techniques. J. Urol. 2003, 169, 666–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, M.; Gilbert, B.R.; Dicker, A.P.; Dwosh, J.; Gnecco, C. Microsurgical inguinal varicocelectomy with delivery of the testis: An artery and lymphatic sparing technique. J. Urol. 1992, 148, 1808–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopps, C.V.; Lemer, M.L.; Schlegel, P.N.; Goldstein, M. Intraoperative varicocele anatomy: A microscopic study of the inguinal versus subinguinal approach. J. Urol. 2003, 170, 2366–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocvara, R.; Dvorácek, J.; Sedlácek, J.; Díte, Z.; Novák, K. Lymphatic sparing laparoscopic varicocelectomy: A microsurgical repair. J. Urol. 2005, 173, 1751–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrilli, A.; Roberti, A.; Escolino, M.; Esposito, C. Surgical approaches for varicocele in pediatric patient. Transl. Pediatr. 2016, 5, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocvara, R.; Dolezal, J.; Hampl, R.; Povýsil, C.; Dvorácek, J.; Hill, M.; Díte, Z.; Stanek, Z.; Novák, K. Division of lymphatic vessels at varicocelectomy leads to testicular oedema and decline in testicular function according to the LH-RH analogue stimulation test. Eur. Urol. 2003, 43, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, C.; Pu, J.; Mei, H.; Zheng, L.; Tong, Q. Lymphatic sparing versus lymphatic non-sparing laparoscopic varicocelectomy in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011, 21, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassberg, K.I.; Poon, S.A.; Gjertson, C.K.; DeCastro, G.J.; Misseri, R. Laparoscopic lymphatic sparing varicocelectomy in adolescents. J. Urol. 2008, 180, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, J.; Körner, I.; Riccabona, M. The use of isosulphan blue to identify lymphatic vessels in high retroperitoneal ligation of adolescent varicocele–avoiding postoperative hydrocele. BJU Int. 2001, 87, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, J.W.S.; Chung, K.L.Y.; Yam, F.S.D.; Lai, N.T.Y.; Suen, M.M.Y.; Chin, V.H.Y.; Leung, M.W.Y. Long lasting effect on testes following methylene blue injection in laparoscopic lymphatic sparing varicocelectomy. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2023, 19, 217.e1–217.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, C.; Iaquinto, M.; Escolino, M.; Cortese, G.; De Pascale, T.; Chiarenza, F.; Cerulo, M.; Settimi, A. Technical standardization of laparoscopic lymphatic sparing varicocelectomy in children using isosulfan blue. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2014, 49, 660–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, C.; Borgogni, R.; Chiodi, A.; Cerulo, M.; Autorino, G.; Esposito, G.; Coppola, V.; Del Conte, F.; Di Mento, C.; Escolino, M. Indocyanine green (ICG)-GUIDED lymphatic sparing laparoscopic varicocelectomy in children and adolescents. Is intratesticular injection of the dye safe? A mid-term follow-up study. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2024, 20, 282.e1–282.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiarenza, S.F.; Giurin, I.; Costa, L.; Alicchio, F.; Carabaich, A.; De Pascale, T.; Settimi, A.; Esposito, C. Blue patent lymphography prevents hydrocele after laparoscopic varicocelectomy: 10 years of experience. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2012, 22, 930–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costabile, R.A.; Skoog, S.; Radowich, M. Testicular volume assessment in the adolescent with a varicocele. J. Urol. 1992, 147, 1348–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madadi-Sanjani, O.; Kuebler, J.F.; Brendel, J.; Wiesner, S.; Mutanen, A.; Eaton, S.; Domenghino, A.; Clavien, P.A.; Ure, B.M. Implementation and validation of a novel instrument for the grading of unexpected events in paediatric surgery: Clavien-Madadi classification. Br. J. Surg. 2023, 110, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubin, L.; Amelar, R.D. Varicocele size and results of varicocelectomy in selected subfertile men with varicocele. Fertil. Steril. 1970, 21, 606–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damsgaard, J.; Joensen, U.N.; Carlsen, E.; Erenpreiss, J.; Blomberg Jensen, M.; Matulevicius, V.; Zilaitiene, B.; Olesen, I.A.; Perheentupa, A. The jamovi Project (2024). Jamovi. (Version 2.5) [Computer Software. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Zampieri, N. Hormonal evaluation in adolescents with varicocele. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2021, 17, 49.e1–49.e5. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33281047/ (accessed on 21 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Van Batavia, J.P.; Lawton, E.; Frazier, J.R.; Zderic, S.A.; Zaontz, M.R.; Shukla, A.R.; Srinivasan, A.K.; Weiss, D.A.; Long, C.J.; Canning, D.A.; et al. Total Motile Sperm Count in Adolescent Boys with Varicocele is Associated with Hormone Levels and Total Testicular Volume. J. Urol. 2021, 205, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The influence of varicocele on parameters of fertility in a large group of men presenting to infertility clinics. Fertil. Steril. 1992, 57, 1289–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, J.A.; Maryam, N.; Kourosh, A. Treatment of varicocele in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2017, 13, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diegidio, P.; Jhaveri, J.K.; Ghannam, S. Review of current varicocelectomy techniques and their outcomes. BJU Int. 2011, 108, 1157–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo, A. Radical cure of varicocele by a new technique: Preliminary report. J. Urol. 1949, 61, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischinger, H.J.; Colombo, T.; Rauchenwald, M.; Altziebler, S.; Steiner, H.; Vilits, P.; Hubmer, G. Laparoscopic procedure for varicocelectomy. Br. J. Urol. 1994, 74, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golebiewski, A.; Krolak, M.; Komasara, L.; Czauderna, P. Dye-assisted lymph vessels sparing laparoscopic varicocelectomy. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2007, 17, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capolicchio, J.P.; El-Sherbiny, M.; Brzezinski, A.; Eassa, W.; Jednak, R. Dye-assisted lymphatic-sparing laparoscopic varicocelectomy in children. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2013, 9, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Gallart, R.; Bautista-Casasnovas, A.; Estevez-Martinez, E.; Varela-Cives, R. Laparoscopic Palomo varicocele surgery: Lessons learned after 10 years’ follow up of 156 consecutive pediatric patients. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2008, 5, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, J.M.; Adams, M.C.; Pope, J.C.; Demarco, R.T.; Brock, J.W., 3rd. Hydrocele formation following laparoscopic varicocelectomy. J. Urol. 2006, 175, 1076–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zundel, S.; Szavay, P.; Hacker, H.-W.; Shavit, S. Adolescent varicocele: Efficacy of indication-to-treat protocol and proposal of a grading system for postoperative hydroceles. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2018, 14, 152.e1–152.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, C.; Escolino, M.; Castagnetti, M.; Cerulo, M.; Settimi, A.; Cortese, G.; Turrà, F.; Iannazzone, M.; Izzo, S.; Servillo, G. Two decades of experience with laparoscopic varicocele repair in children: Standardizing the technique. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2018, 14, 10.e1–10.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Chiba, K.; Yamaguchi, K.; Okada, K.; Matsushita, K.; Ando, M.; Yue, H.; Fujisawa, M. Effect of varicocelectomy on testicular volume in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Urology 2012, 79, 1340–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.L.; Tecson, B.; Ee, M.Z.; Tantoco, J. Lymphatic sparing, laparoscopic varicocelectomy: A new surgical technique. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2004, 20, 797–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd Ellatif, M.E.; El Nakeeb, A.; Shoma, A.M.; Abbas, A.E.; Askar, W.; Noman, N. Dye assisted lymphatic sparing subinguinal varicocelectomy. A prospective randomized study. Int. J. Surg. 2011, 9, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alessio, A.; Piro, E.; Beretta, F.; Brugnoni, M.; Marinoni, F.; Abati, L. Lymphatic preservation using methylene blue dye during varicocele surgery: A single-center retrospective study. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2008, 4, 138–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perenyei, M.; Barber, Z.E.; Gibson, J.; Hemington-Gorse, S.; Dobbs, T.D. Anaphylactic Reaction Rates to Blue Dyes Used for Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. 2021, 273, 1087–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makari, J.H.; Atalla, M.A.; Belman, A.B.; Rushton, H.G.; Kumar, S.; Pohl, H.G. Safety and efficacy of intratesticular injection of vital dyes for lymphatic preservation during varicocelectomy. J. Urol. 2007, 178, 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fast, A.M.; Deibert, C.M.; Van Batavia, J.P.; Nees, S.N.; Glassberg, K.I. Adolescent varicocelectomy: Does artery sparing influence recurrence rate and/or catch-up growth? Andrology 2014, 2, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagır, S.; Azizoglu, M. Varicocele Surgery: Three Years Experience: Varicocele Surgery. Pak. Biomed. J. 2023, 6, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camoglio, F.S.; Zampieri, N. Varicocele treatment in paediatric age: Relationship between type of vein reflux, surgical technique used and outcomes. Andrologia 2016, 48, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares-Aquino, C.; Vasconcelos-Castro, S.; Campos, J.M.; Soares-Oliveira, M. 15-Year varicocelectomy outcomes in pediatric age: Beware of genitofemoral nerve injury. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2021, 17, 537.e1–537.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n (%); Median (Q1–Q3) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 15 (13.5–17) |

| Side (left) | 21 (100%) |

| Grade 3 varicocele | 21 (100%) |

| Lymphatic sparing | 7 (33.3%) |

| Arterial sparing | 4 (19%) |

| Preoperative RTV (mL) | 6.8 (3.48–7.5) |

| Preoperative LTV (mL) | 5.98 (3.33–7.6) |

| Preoperative RTV-to-LTV (mL) | 0.23 (−0.685–2.15) |

| Postoperative RTV (mL) | 7.04 (3.87–8.05) |

| Postoperative LTV (mL) | 5.96 (4.62–8.48) |

| Postoperative RTV-to-LTV (mL) | 0.05 (−0.717–1.21) |

| Change in RTV (%) | 38 (5.74–129) |

| Change in LTV (%) | 72.5 (−21.9–145) |

| Hydrocele | 3 (14.3%) |

| Calcification | 4 (19%) |

| Recurrence | 4 (19%) |

| Clavien-Madadi Classification | |

| 1 | 6 (29%) |

| 3B | 3 (14.3%) |

| Non-Lymphatic Sparing (n = 14) | Lymphatic Sparing (n = 7) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15.5 (15–17) | 13 (11.5–16) | 0.247 |

| Side (left) | 14 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 1.000 |

| Grade 3 varicocele | 14 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 1.000 |

| Arterial sparing | 4 (28.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.116 |

| Preoperative RTV (mL) | 6.8 (2.73–7.56) | 6.72 (2.73–7.36) | 1.000 |

| Preoperative LTV (mL) | 6.03 (3.53–7.32) | 5.20 (2.60–8.36) | 0.966 |

| Preoperative RTV-to-LTV (mL) | 0.16 (−1.07–2.24) | 1.14 (−0.168–2.06) | 1.000 |

| Postoperative RTV (mL) | 7.74 (7.03–8.71) | 4.5 (3.66–6.65) | 0.147 |

| Postoperative LTV (mL) | 6.5 (4.39–8.71) | 4.48 (4.39–5.73) | 0.286 |

| Postoperative RTV-to-LTV (mL) | 0.2 (−0.56–1.24) | −0.46 (−1.29–0.11) | 0.364 |

| Change in RTV (%) | 38% (5.74–98) | 68.8% (4.50–146) | 0.933 |

| Change in LTV (%) | 34.6% (−21.9–122) | 110% (47.1–179) | 0.683 |

| Hydrocele | 2 (14.3%) | 1 (14.3%) | 1.000 |

| Calcification | 0 (0%) | 4 (57.1%) | 0.002 |

| Recurrence | 3 (21.4%) | 1 (14.3%) | 0.694 |

| Follow-up (year) | 5.5 (2.5; 7) | 3 (2; 3) | 0.077 |

| Clavien-Madadi Classification | 0.343 | ||

| 1 | 2 (50%) | 4 (80%) | |

| 3B | 2 (50%) | 1 (20%) |

| No Arterial Sparing (n = 17) | Arterial Sparing (n = 4) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15.5 (13.5–17) | 15 (14–15.5) | 0.711 |

| Side (left) | 17 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 1.000 |

| Grade 3 varicocele | 17 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 1.000 |

| Preoperative RTV (mL) | 6.8 (3.6–7.5) | 5.6 (3.3–6.6) | 0.559 |

| Preoperative LTV (mL) | 6.2 (4.6–7.92) | 3.12 (2.08–3.33) | 0.064 |

| Preoperative RTV-to-LTV (mL) | 0.2 (−1.20–2.05) | 2.5 (1.17–3.27) | 0.171 |

| Postoperative RTV (mL) | 6.84 (3.54–7.43) | 8.43 (8.29–8.57) | 0.198 |

| Postoperative LTV (mL) | 5.67 (4.46–6.83) | 8.71 (8.71–8.71) | 0.170 |

| Postoperative RTV-to-LTV (mL) | 0.155 (−0.9–1.26) | −0.28 (−0.42–−0.14) | 0.659 |

| Change in RTV (%) | 60.8% (3.82–130) | 15.2% (15.2–15.2) | 1.000 |

| Change in LTV (%) | 69.3% (−22.4–129) | 147 (147–147) | 0.5 |

| Hydrocele | 2 (11.8%) | 1 (25%) | 0.496 |

| Calcification | 4 (23.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.281 |

| Recurrence | 4 (23.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.281 |

| Clavien-Madadi Classification | 0.134 | ||

| 1 | 6 (75%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 3B | 2 (25%) | 1 (100%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Canmemis, A.; Caglar, M.; Ulukaya Durakbasa, C. Retrospective Analysis of Laparoscopic Varicocelectomy in Pediatric Patients: Impact of Lymphatic-Sparing Techniques and Methylene Blue on Outcomes—A Series of Cases. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3814. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113814

Canmemis A, Caglar M, Ulukaya Durakbasa C. Retrospective Analysis of Laparoscopic Varicocelectomy in Pediatric Patients: Impact of Lymphatic-Sparing Techniques and Methylene Blue on Outcomes—A Series of Cases. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(11):3814. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113814

Chicago/Turabian StyleCanmemis, Arzu, Meltem Caglar, and Cigdem Ulukaya Durakbasa. 2025. "Retrospective Analysis of Laparoscopic Varicocelectomy in Pediatric Patients: Impact of Lymphatic-Sparing Techniques and Methylene Blue on Outcomes—A Series of Cases" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 11: 3814. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113814

APA StyleCanmemis, A., Caglar, M., & Ulukaya Durakbasa, C. (2025). Retrospective Analysis of Laparoscopic Varicocelectomy in Pediatric Patients: Impact of Lymphatic-Sparing Techniques and Methylene Blue on Outcomes—A Series of Cases. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(11), 3814. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113814