Prevalence of Joint Complaints in Patients with Celiac Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Identification of Patients and Outcome

2.2.1. Celiac Disease

2.2.2. Joint Complaints

2.3. Data Items and Risk of Bias

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Statement

3. Results

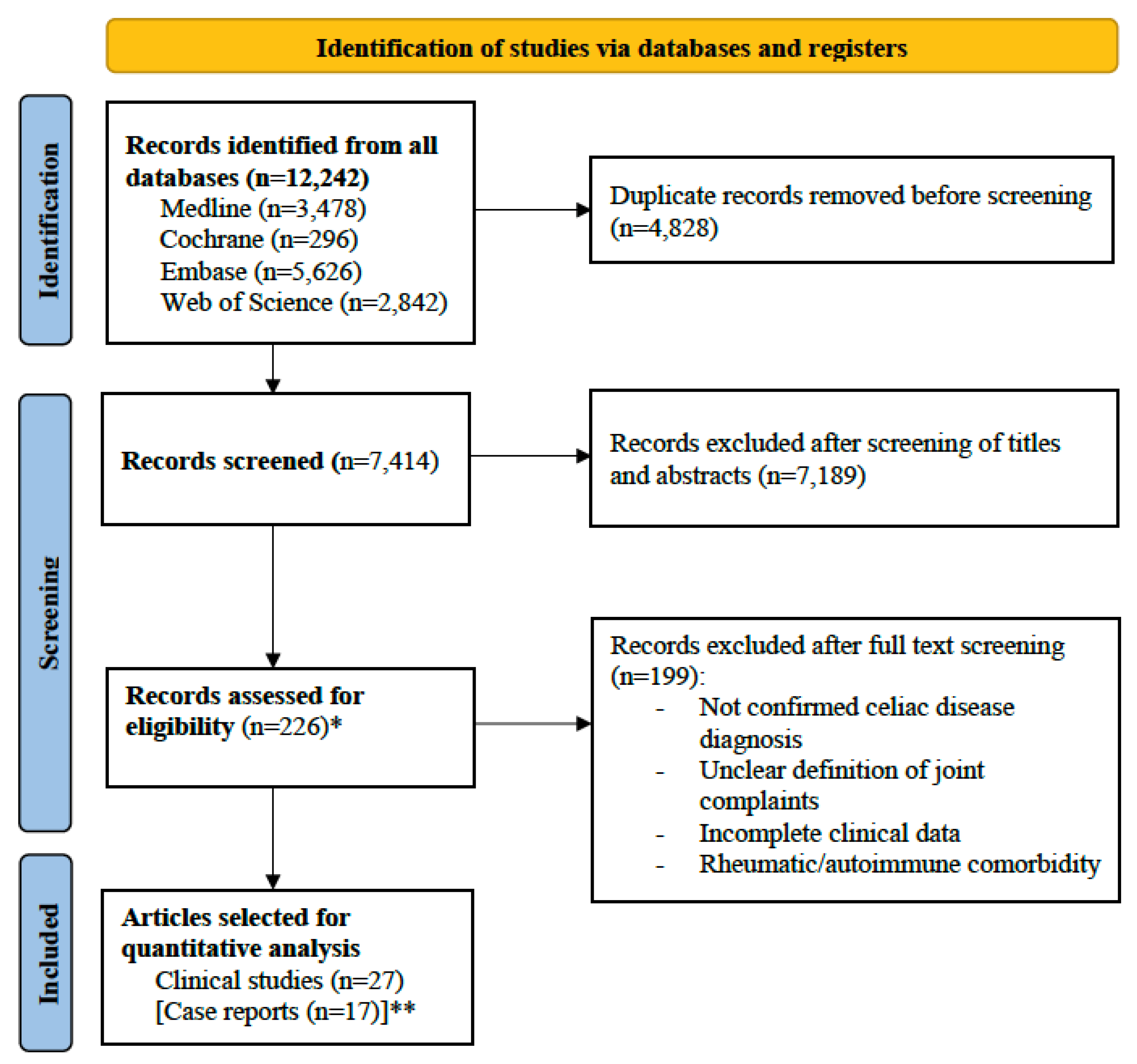

3.1. Literature Research Output

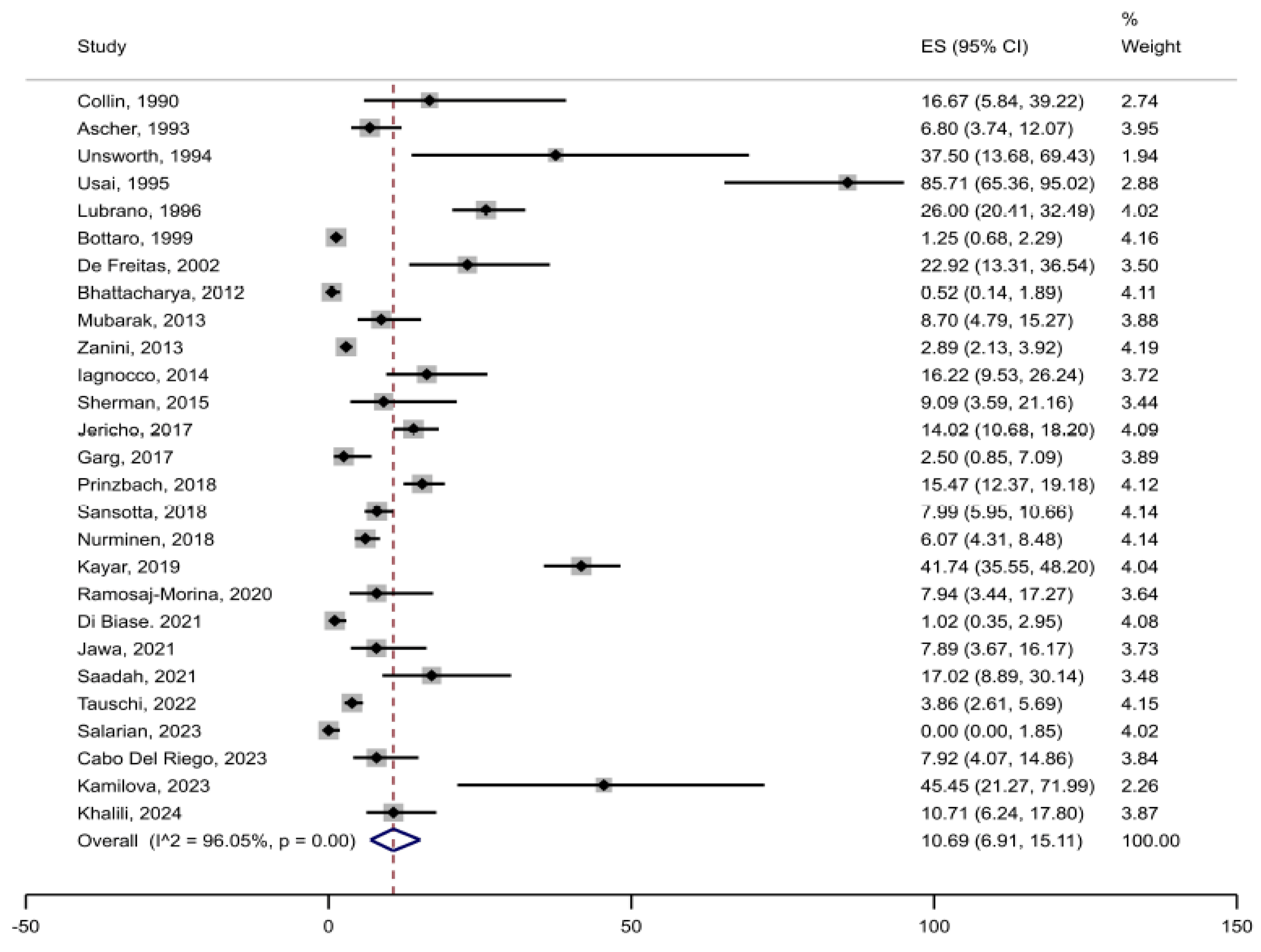

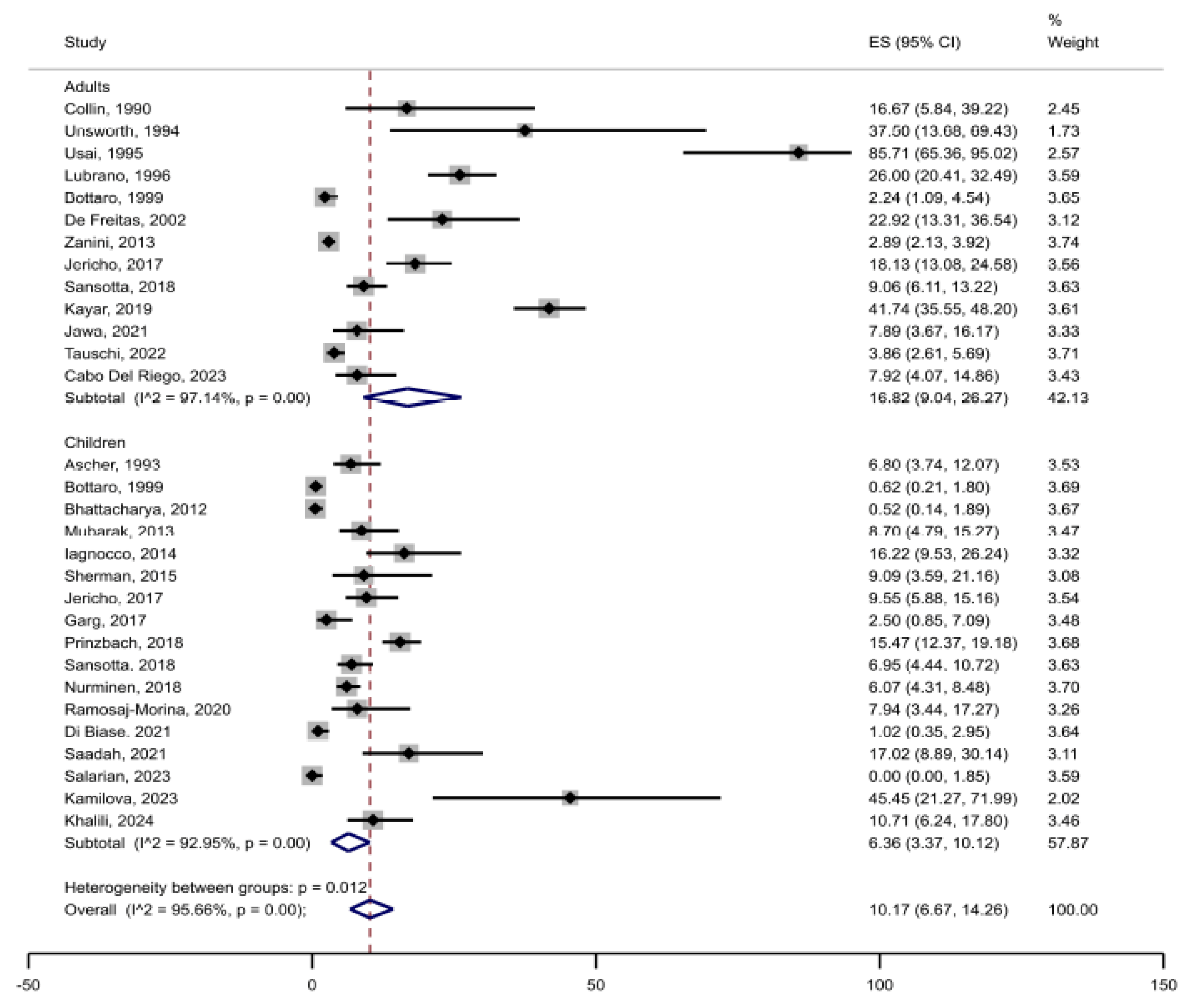

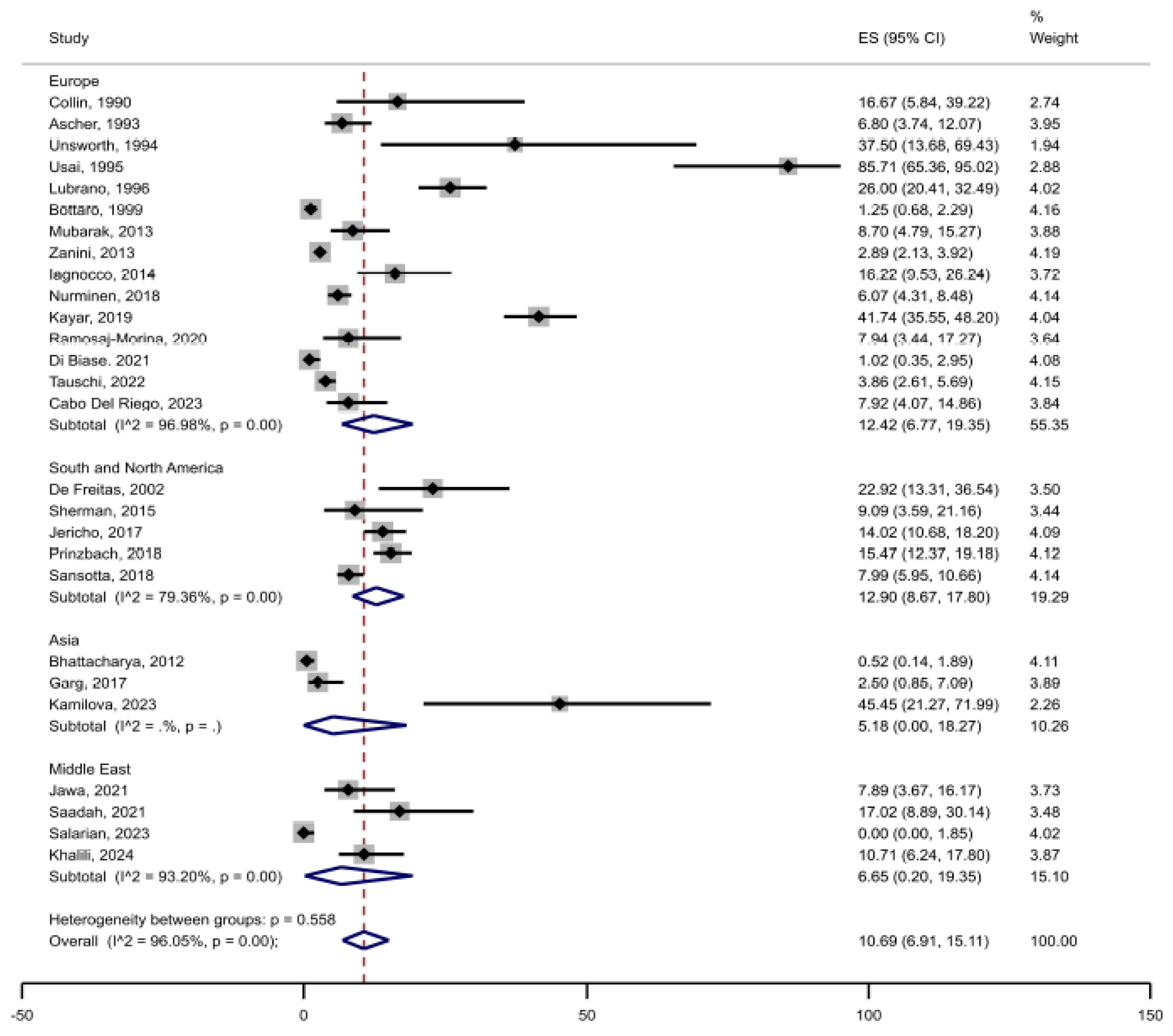

3.2. Prevalence of Joint Complaints in Celiac Disease

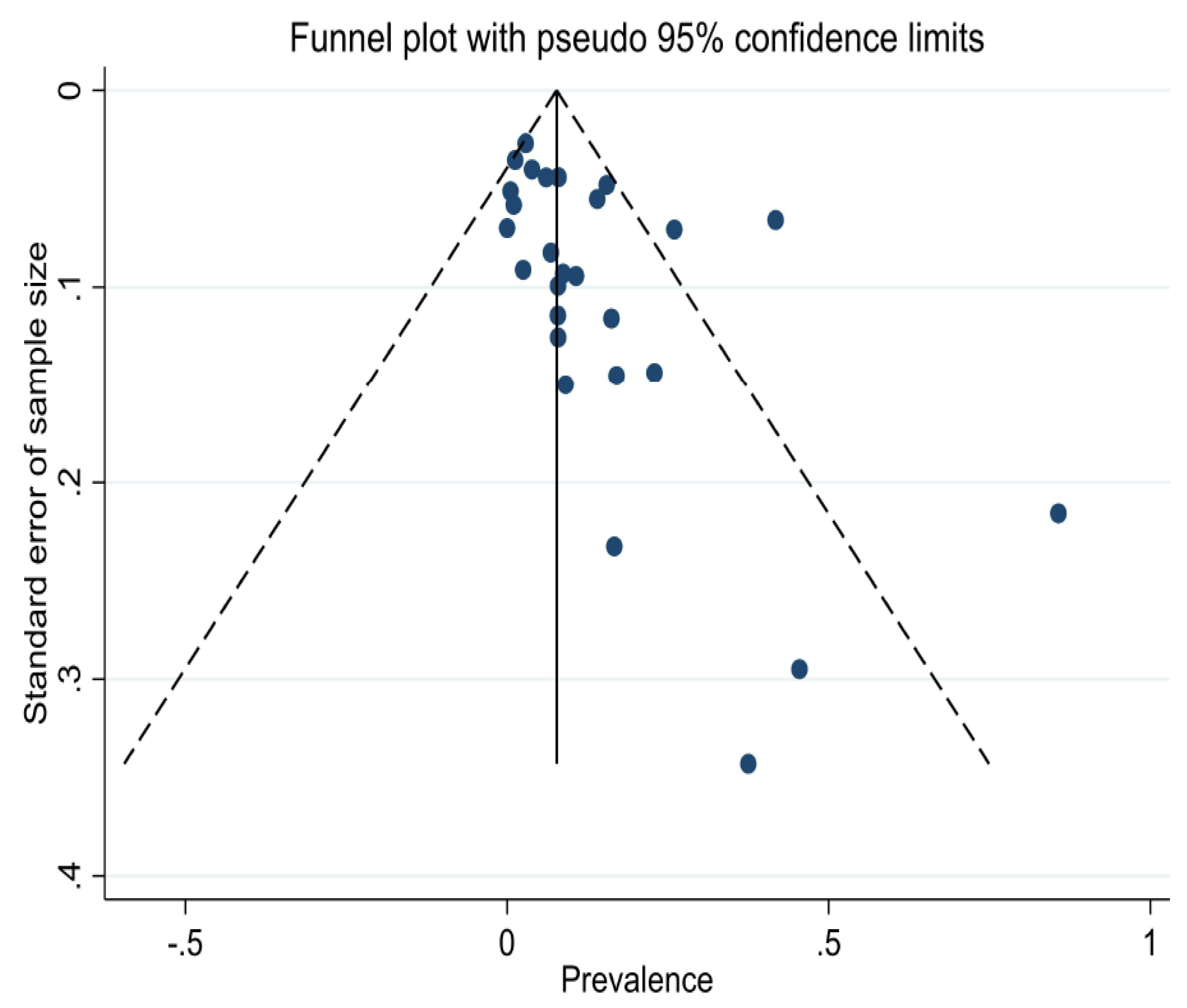

3.3. Risk of Bias and Heterogeneity

3.4. Case Reports

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Catassi, C.; Verdu, E.F.; Bai, J.C.; Lionetti, E. Coeliac disease. Lancet 2022, 399, 2413–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caio, G.; Volta, U.; Sapone, A.; Leffler, D.A.; De Giorgio, R.; Catassi, C.; Fasano, A. Celiac disease: A comprehensive current review. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guandalini, S.; Assiri, A. Celiac disease: A review. JAMA Pediatr. 2014, 168, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zingone, F.; Bai, J.C.; Cellier, C.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Celiac disease-related conditions: Who to test? Gastroenterology 2024, 167, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volta, U.; Caio, G.; Stanghellini, V.; De Giorgio, R. The changing clinical profile of celiac disease: A 15-year experience (1998–2012) in an Italian referral center. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014, 14, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forss, A.; Sotoodeh, A.; van Vollenhoven, R.F.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Prevalence of coeliac disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2024, 42, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poddighe, D.; Romano, M.; Dossybayeva, K.; Abdukhakimova, D.; Galiyeva, D.; Demirkaya, E. Celiac disease in juvenile idiopathic arthritis and other pediatric rheumatic disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelatos, G.; Kouna, K.; Iliopoulos, A.; Fragoulis, G.E. Musculoskeletal complications of celiac disease: A case-based review. Mediterr. J. Rheumatol. 2023, 34, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, A.; Kelly, C.P.; Silvester, J.A. Celiac disease: Extraintestinal manifestations and associated conditions. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2020, 54, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, A.; Shoenfeld, Y.; Matthias, T. Adverse effects of gluten ingestion and advantages of gluten withdrawal in nonceliac autoimmune disease. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 1046–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Moola, S.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C.; Munn, Z. Chapter 5: Systematic reviews of prevalence and incidence. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Collin, P.; Hällström, O.; Mäki, M.; Viander, M.; Keyriläinen, O. Atypical coeliac disease found with serologic screening. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1990, 25, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascher, H.; Holm, K.; Kristiansson, B.; Mäki, M. Different features of coeliac disease in two neighbouring countries. Arch. Dis. Child. 1993, 69, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unsworth, D.J.; Brown, D.L. Serological screening suggests that adult coeliac disease is underdiagnosed in the UK and increases the incidence by up to 12%. Gut 1994, 35, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usai, P.; Boi, M.F.; Piga, M.; Cacace, E.; Lai, M.A.; Beccaris, A.; Piras, E.; La Nasa, G.; Mulargia, M.; Balestrieri, A. Adult celiac disease is frequently associated with sacroiliitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1995, 40, 1906–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubrano, E.; Ciacci, C.; Ames, P.R.; Mazzacca, G.; Oriente, P.; Scarpa, R. The arthritis of coeliac disease: Prevalence and pattern in 200 adult patients. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1996, 35, 1314–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottaro, G.; Cataldo, F.; Rotolo, N.; Spina, M.; Corazza, G.R. The clinical pattern of subclinical/silent celiac disease: An analysis on 1026 consecutive cases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1999, 94, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, I.N.; Sipahi, A.M.; Damião, A.O.; de Brito, T.; Cançado, E.L.; Leser, P.G.; Laudanna, A.A. Celiac disease in Brazilian adults. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2002, 34, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Kapoor, S.; Dubey, A.P. Celiac disease presentation in a tertiary referral centre in India: Current scenario. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 32, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, A.; Spierings, E.; Wolters, V.M.; Otten, H.G.; ten Kate, F.J.; Houwen, R.H. Children with celiac disease and high tTGA are genetically and phenotypically different. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 7114–7120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, B.; Caselani, F.; Magni, A.; Turini, D.; Ferraresi, A.; Lanzarotto, F.; Villanacci, V.; Carabellese, N.; Ricci, C.; Lanzini, A. Celiac disease with mild enteropathy is not mild disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 11, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iagnocco, A.; Ceccarelli, F.; Mennini, M.; Rutigliano, I.M.; Perricone, C.; Nenna, R.; Petrarca, L.; Mastrogiorgio, G.; Valesini, G.; Bonamico, M. Subclinical synovitis detected by ultrasound in children affected by coeliac disease: A frequent manifestation improved by a gluten-free diet. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2014, 32, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, Y.; Karanicolas, R.; DiMarco, B.; Pan, N.; Adams, A.B.; Barinstein, L.V.; Moorthy, L.N.; Lehman, T.J. Unrecognized celiac disease in children presenting for rheumatology evaluation. Pediatrics 2015, 136, e68–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jericho, H.; Sansotta, N.; Guandalini, S. Extraintestinal manifestations of celiac disease: Effectiveness of the gluten-free diet. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 65, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, K.; Agarwal, P.; Gupta, R.K.; Sitaraman, S. Joint involvement in children with celiac disease. Indian Pediatr. 2017, 54, 946–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinzbach, A.; Moosavinasab, S.; Rust, S.; Boyle, B.; Barnard, J.A.; Huang, Y.; Lin, S. Comorbidities in childhood celiac disease: A phenome-wide association study using the electronic health record. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 67, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansotta, N.; Amirikian, K.; Guandalini, S.; Jericho, H. Celiac disease symptom resolution: Effectiveness of the gluten-free diet. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 66, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurminen, S.; Kivelä, L.; Huhtala, H.; Kaukinen, K.; Kurppa, K. Extraintestinal manifestations were common in children with coeliac disease and were more prevalent in patients with more severe clinical and histological presentation. Acta Paediatr. 2019, 108, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayar, Y.; Dertli, R.; Surmeli, N.; Bilgili, M.A. Extraintestinal manifestations associated with celiac disease. East. J. Med. 2019, 24, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramosaj-Morina, A.; Keka-Sylaj, A.; Zejnullahu, A.B.; Spahiu, L.; Hasbahta, V.; Jaha, V.; Kotori, V.; Bicaj, B.; Kurshumliu, F.; Zhjeqi, V.; et al. Celiac disease in Kosovar Albanian children: Evaluation of clinical features and diagnosis. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2020, 16, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Biase, A.R.; Marasco, G.; Ravaioli, F.; Colecchia, L.; Dajti, E.; Lecis, M.; Passini, E.; Alemanni, L.V.; Festi, D.; Iughetti, L.; et al. Clinical presentation of celiac disease and diagnosis accuracy in a single-center European pediatric cohort over 10 years. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawa, H.; Khatib, H.; Almani, I.; Etaiwi, A.; Alharbi, A.; Ajaj, A.; Alsahafi, M.; Bokhary, R.; Mosli, M.; Qari, Y. Normalization of anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies in patients with histologically confirmed celiac disease: A retrospective analysis. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 2021, 11, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar]

- Saadah, O.I. The impact of a gluten-free diet on the growth pattern of Saudi children with celiac disease. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2021, 71, 1573–1578. [Google Scholar]

- Tauschi, R.; Eurén, A.; Vuorela, N.; Koskimaa, S.; Huhtala, H.; Kaukinen, K.; Kivelä, L.; Kurppa, K. Association of concomitant autoimmunity with disease features and long-term treatment and health outcomes in celiac disease. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1055135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salarian, L.; Khavaran, M.; Dehghani, S.M.; Mashhadiagha, A.; Moosavi, S.A.; Rezaeianzadeh, S. Extra-intestinal manifestations of celiac disease in children: Their prevalence and association with human leukocyte antigens and pathological and laboratory evaluations. BMC Pediatr. 2023, 23, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabo Del Riego, J.M.; Núñez-Iglesias, M.J.; Paz Carreira, J.; Blanco Hortas, A.; Álvarez Fernández, T.; Novío Mallón, S.; Zaera, S.; Freire-Garabal Núñez, M. Red cell distribution width as a predictive factor of celiac disease in middle and late adulthood and its potential utility as a screening criterion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamilova, A.T.; Azizova, G.K.; Poddighe, D.; Umarnazarova, Z.E.; Abdullaeva, D.A.; Geller, S.I.; Azimova, N.D. Celiac disease in Uzbek children: Insights into disease prevalence and clinical characteristics in symptomatic pediatric patients. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, M.; Sadeghi Zarchi, M.; Teimouri, A.; Ansari-Moghaddam, A.; Rafaiee, R. Evaluating the frequency and cause of persistent symptoms in pediatric patients with celiac disease adhering to a long-term gluten-free diet. J. Compr. Pediatr. 2024, 15, e138752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, J.E.; Griffiths, I.D. Arthritis—A presenting feature of occult coeliac disease. Bristol Med. J. 1992, 31, 857–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T.A.; Hochman, R.F.; Scopelliti, J.A. Celiac Disease and Arthropathy: Case Report and Literature Review. Guthrie J. 1993, 62, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, G.D.; Hankey, G.L.; Holmes, G.K. Oligoarthritis—A presenting feature of occult coeliac disease. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1993, 32, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khattak, F.H.; Mattingly, P.C. Oligoarthritis associated with celiac disease. Irish Med. J. 1994, 87, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, A.A.; Dawes, P.T.; Swan, C.H.; Hothersall, T.E. Persistent monoarthritis and occult coeliac disease. Postgrad. Med. J. 1994, 70, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enzenauer, R.J.; Root, S. Arthropathy and celiac disease. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 1998, 4, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcini, F.; Ferrari, R.; Simonini, G.; Calabri, G.B.; Pazzaglia, A.; Lionetti, P. Recurrent monoarthritis in an 11-year-old boy with occult coeliac disease: Successful and stable remission after gluten-free diet. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 1999, 17, 509–511. [Google Scholar]

- Bagnato, G.F.; Quattrocchi, E.; Gulli, S.; Giacobbe, O.; Chirico, G.; Romano, C.; Purello D’Ambrosio, F. Unusual polyarthritis as a clinical manifestation of coeliac disease. Rheumatol. Int. 2000, 20, 29–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, A.L.; Kaye, S.A. Oligoarthritis in an elderly woman with diarrhoea and weight loss. Postgrad. Med. J. 2001, 77, 475–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Slot, O.; Locht, H. Arthritis as presenting symptom in silent adult coeliac disease: Two cases and review of the literature. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2000, 29, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawidowicz, K.; Ea, H.K.; Lahalle, S.; Qubaja, M.; Lioté, F. Unexplained polyarthralgia and celiac disease. Joint Bone Spine 2008, 75, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efe, C.; Urün, Y.; Purnak, T.; Ozaslan, E.; Ozbalkan, Z.; Savaşs, B. Silent celiac disease presenting with polyarthritis. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2010, 16, 195–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyemisci-Taskiran, O.; Cengiz, M.; Atalay, F. Celiac disease of the joint. Rheumatol. Int. 2011, 31, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priyadarshini, S.; Asghar, A.; Shabih, S.; Kasireddy, V. Celiac Disease Masquerading as Arthralgia. Cureus 2022, 14, e26387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougui, A.; El Bouchti, I. Isolated polyarthritis revealing celiac disease: A case report. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 2023, 11, 2050313X231186305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçükali, B.; Bayrak, H.; Yıldırım, D.G.; İnci, A.; Bakkaloğlu, S.A.; Tümer, L. A 7-year-old boy with scurvy owing to coeliac disease. Paediatr. Int. Child Health 2024, 44, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigden, M.L. Clinical utility of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Am. Fam. Physician 1999, 60, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar]

- Dima, A.; Jurcut, C.; Jinga, M. Rheumatologic manifestations in celiac disease: What should we remember? Rom. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 57, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zylberberg, H.M.; Lebwohl, B.; Green, P.H.R. Celiac disease-musculoskeletal manifestations and mechanisms in children to adults. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2018, 16, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, J.B.; Lebwohl, B.; Askling, J.; Forss, A.; Green, P.H.R.; Roelstraete, B.; Söderling, J.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Risk of juvenile idiopathic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis in patients with celiac disease: A population-based cohort study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 1971–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naddei, R.; Di Gennaro, S.; Guarino, A.; Troncone, R.; Alessio, M.; Discepolo, V. In a large juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) cohort, concomitant celiac disease is associated with family history of autoimmunity and a more severe JIA course: A retrospective study. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 2022, 20, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beas, R.; Altamirano-Farfan, E.; Izquierdo-Veraza, D.; Norwood, D.A.; Riva-Moscoso, A.; Godoy, A.; Montalvan-Sanchez, E.E.; Ramirez, M.; Guifarro, D.A.; Kitchin, E.; et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren syndrome and systemic sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig. Liver Dis. 2024, 56, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoloni, E.; Bistoni, O.; Alunno, A.; Cavagna, L.; Nalotto, L.; Baldini, C.; Priori, R.; Fischetti, C.; Fredi, M.; Quartuccio, L.; et al. Celiac disease prevalence is increased in primary Sjögren’s syndrome and diffuse systemic sclerosis: Lessons from a large multi-center study. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotoodeh, A.; Nguyen Hoang, M.; Hellgren, K.; Forss, A. Prevalence of celiac disease in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lupus Sci. Med. 2024, 11, e001106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rensch, M.J.; Szyjkowski, R.; Shaffer, R.T.; Fink, S.; Kopecky, C.; Grissmer, L.; Enzenhauer, R.; Kadakia, S. The prevalence of celiac disease autoantibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2001, 96, 1113–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erbasan, F.; Çoban, D.T.; Karasu, U.; Çekin, Y.; Yeşil, B.; Çekin, A.H.; Süren, D.; Terzioğlu, M.E. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome in patients with celiac disease. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 47, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhning, D.; Lerdsuwansri, R.; Holling, H. Some general points on the -measure of heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Metrika 2017, 80, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors, Year | Study Design | Country | Patients with CD (n) | Age Group | Females (%) | Mean Age (Years) | Arthalgia (n) | Arthritis (n) | Joint Complaints Total [n (%)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collin et al., 1990 [13] | Retrospective cohort study | Finland | 18 | Adults | 78 | 41.6 | 2 | 1 | 3 (17) |

| Ascher et al., 1993 [14] | Retrospective cohort study | Finland/ Sweden | 147 | Children | 62 | 5.00 | 10 | 0 | 10 (7) |

| Unsworth et al., 1994 [15] | Retrospective cohort study | United Kingdom | 8 | Adults | 75 | 51.8 | 3 | 0 | 3 (38) |

| Usai et al., 1995 [16] | Retrospective cohort study | Italy | 21 | Adults | 71 | 36.7 | 18 | 0 | 18 (86) |

| Lubrano et al., 1996 [17] | Retrospective cohort study | Italy | 200 | Adults | 77 | 34.8 | 0 | 52 | 52 (26) |

| Bottaro et al., 1999 [18] | Retrospective cohort study | Italy | 485 | Children | - | 7.7 | 3 | 0 | 3 (1) |

| “ | “ | “ | 313 | Adults | - | 24.4 | 7 | 0 | 7 (2) |

| De Freitas et al., 2002 [19] | Retrospective cohort study | Brazil | 48 | Adults | 67 | 41.0 | 11 | 0 | 11 (23) |

| Bhattacharya et al, 2012 [20] | Retrospective cohort study | India | 381 | Children | 42 | 6.2 | 0 | 2 | 2 (1) |

| Mubarak et al., 2013 [21] | Retrospective cohort study | The Netherlands | 115 | Children | 72 | 6.5 | 10 | 0 | 10 (9) |

| Zanini et al., 2013 [22] | Retrospective cohort study | Italy | 1382 | Adults | - | - | 40 | 0 | 40 (3) |

| Iagnocco et al., 2014 [23] | Retrospective cohort study | Italy | 74 | Children | 70 | 7.6 | 12 | 0 | 12 (16) |

| Sherman et al., 2015 [24] | Retrospective cohort study | USA | 44 | Children | 84 | 9.8 | 4 | 0 | 4 (9) |

| Jericho et al., 2017 [25] | Retrospective cohort study | USA | 157 | Children | - | 8.9 | 11 | 4 | 15 (10) |

| “ | “ | “ | 171 | Adults | - | 40.6 | 15 | 16 | 31 (18) |

| Garg et al., 2017 [26] | Cross-sectional study | India | 120 | Children | 48 | 6.7 | 3 | 0 | 3 (3) |

| Prinzbach et al., 2018 [27] | Retrospective cohort study | USA | 433 | Children | 61 | 9.5 | 67 | 0 | 67 (15) |

| Sansotta et al., 2018 [28] | Retrospective cohort study | USA | 259 | Children | 66 | - | 18 | 0 | 18 (7) |

| “ | “ | “ | 254 | Adults | 78 | - | 23 | 0 | 23 (9) |

| Nurminen et al., 2018 [29] | Retrospective cohort study | Finland | 511 | Children | 65 | - | 31 | 0 | 31 (6) |

| Kayar et al., 2019 [30] | Retrospective cohort study | Turkey | 230 | Adults | 75 | 33.4 | 96 | 0 | 96 (42) |

| Ramosaj-Morina et al., 2020 [31] | Retrospective cohort study | Kosovo | 63 | Children | 63 | 5.5 | 5 | 0 | 5 (8) |

| Di Biase et al., 2021 [32] | Retrospective cohort study | Italy | 295 | Children | - | 6.4 | 0 | 3 | 3 (1) |

| Jawa et al., 2021 [33] | Retrospective cohort study | Saudi Arabia | 76 | Adults | 58 | 30.5 | 0 | 6 | 6 (8) |

| Saadah et al., 2021 [34] | Retrospective cohort study | Saudi Arabia | 47 | Children | 47 | 8.7 | 8 | 0 | 8 (17) |

| Tauschi et al., 2022 [35] | Retrospective cohort study | Finland | 621 | Adults | 74 | - | 24 | 0 | 24 (4) |

| Salarian et al., 2023 [36] | Cross-sectional study | Iran | 204 | Children | 62 | 8.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Cabo Del Riego et al., 2023 [37] | Retrospective cohort study | Spain | 101 | Adults | 68 | 63.0 | 8 | 0 | 8 (8) |

| Kamilova et al., 2023 [38] | Retrospective cohort study | Uzbekistan | 11 | Children | 55 | 5.7 | 5 | 0 | 5 (45) |

| Khalili et al., 2024 [39] | Cross-sectional study | Iran | 112 | Children | 54 | 6.8 | 12 | 0 | 12 (11) |

| Study | Prevalence (%, 95% Confidence Interval) * | I2 (%) * |

|---|---|---|

| Collin, 1990 [13] | 10.57 (6.77–15.02) | 96.18 |

| Ascher, 1993 [14] | 10.90 (6.97–15.52) | 96.20 |

| Unsworth, 1994 [15] | 10.42 (6.70–14.80) | 96.16 |

| Usai, 1995 [16] | 9.14 (5.75–13.15) | 95.73 |

| Lubrano, 1996 [17] | 10.07 (6.44–14.34) | 95.75 |

| Bottaro, 1999 [18] | 11.34 (7.33–16.03) | 95.79 |

| De Freitas, 2002 [19] | 10.31 (6.55–14.73) | 96.12 |

| Bhattacharya, 2012 [20] | 11.40 (7.44–16.02) | 95.92 |

| Mubarak, 2013 [21] | 10.80 (6.89–15.38) | 96.19 |

| Zanini, 2013 [22] | 11.30 (7.10–16.26) | 95.95 |

| Iagnocco, 2014 [23] | 10.49 (6.68–14.98) | 96.15 |

| Sherman, 2015 [24] | 10.76 (6.89–15.29) | 96.19 |

| Jericho, 2017 [25] | 10.57 (6.71–15.12) | 96.04 |

| Garg, 2017 [26] | 11.15 (7.19–15.78) | 96.18 |

| Prinzbach, 2018 [27] | 10.50 (6.67–15.00) | 95.91 |

| Sansotta, 2018 [28] | 10.91 (6.88–15.66) | 96.18 |

| Nurminen, 2018 [29] | 11.02 (6.96–15.80) | 96.20 |

| Kayar, 2019 [30] | 9.34 (6.17–13.02) | 94.57 |

| Ramosaj-Morina, 2020 [31] | 10.81 (6.93–15.37) | 96.19 |

| Di Biase, 2021 [32] | 11.34 (7.35–15.99) | 96.05 |

| Jawa, 2021 [33] | 10.82 (6.93–15.39) | 96.19 |

| Saadah, 2021 [34] | 10.48 (6.68–14.96) | 96.16 |

| Tauschi, 2022 [35] | 11.17 (7.07–15.99) | 96.16 |

| Salarian, 2023 [36] | 11.49 (7.55–16.08) | 95.96 |

| Cabo Del Riego, 2023 [37] | 10.83 (6.93–15.41) | 96.19 |

| Kamilova, 2023 [38] | 10.19 (6.50–14.54) | 96.13 |

| Khalili, 2024 [39] | 10.71 (6.83–15.26) | 96.18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poddighe, D.; Zhubanova, G.; Galiyeva, D.; Mussina, K.; Forss, A. Prevalence of Joint Complaints in Patients with Celiac Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3740. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113740

Poddighe D, Zhubanova G, Galiyeva D, Mussina K, Forss A. Prevalence of Joint Complaints in Patients with Celiac Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(11):3740. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113740

Chicago/Turabian StylePoddighe, Dimitri, Gulsamal Zhubanova, Dinara Galiyeva, Kamilla Mussina, and Anders Forss. 2025. "Prevalence of Joint Complaints in Patients with Celiac Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 11: 3740. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113740

APA StylePoddighe, D., Zhubanova, G., Galiyeva, D., Mussina, K., & Forss, A. (2025). Prevalence of Joint Complaints in Patients with Celiac Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(11), 3740. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113740