1. Introduction

Breast reconstruction following mastectomy is a life-quality enhancing aspect of comprehensive care for breast cancer patients, offering these women an opportunity to regain both physical and psychological well-being [

1]. When it comes to autologous breast reconstruction, the Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator (DIEP) flap has been considered the gold standard for many years [

2,

3,

4]. However, the Profunda Artery Perforator (PAP) flap, introduced by Allen in 2012 [

5], has emerged as a promising alternative to the Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator (DIEP) flap [

3,

4,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Specifically for women who lack sufficient donor tissue or for those where abdominal tissue is no longer an option, such as due to scarring from prior surgeries, previous scientific studies have shown that the PAP flap is a valuable alternative [

8]. Also, a recent study conducted by our research group demonstrated similar results in terms of donor site morbidity, scar quality, and the aesthetic outcome of the breast comparing the PAP flap and the DIEP flap [

11]. Additionally, the PAP flap has not only gained increasing recognition for other indications in recent years, such as lower extremity and head or neck reconstruction, but also for coverage of the ischial or perineal regions [

12,

13]. In our Department, we offer the PAP flap to slim patients for whom a DIEP flap is not feasible but who still desire autologous tissue reconstruction. As a result, our patient cohort of breast reconstruction with PAP flap tends to be lean with an average BMI of 23.3 kg/m

2 (vertical skin island group: 23.9 kg/m

2, range: 19.4–32.4 kg/m

2, horizontal skin island group: 22.7 kg/m

2, range: 18.5–27.5 kg/m

2). In other studies, the BMI of the patients was reported to be higher, ranging from 23.3 kg/m

2 to 29.1 kg/m

2 [

5,

6,

14,

15]. Early descriptions of the PAP flap involved a horizontal skin island, which raised concerns related to thigh undermining and suboptimal scarring [

14,

15]. These complications were even more evident in our patient cohort due to the low BMI. Jo et al. [

8] also used the PAP flap for slim patients (average BMI = 22.2 kg/m

2) with 4.2% donor site wound necrosis. Several modifications of the skin island design have been introduced to optimize the donor site complication rates, such as an extended design [

16], a fleur-de-lis design [

17], or a vertical design [

18,

19,

20]. To address these challenges, we aimed to explore the potential advantages of utilizing a vertical skin island in PAP flap breast reconstruction compared to the horizontal flap island design. To our knowledge, no study has yet compared the aesthetic outcomes and complication rates of the vertical and horizontal skin island in PAP flap breast reconstruction. We believe that the adjusted skin island design positively affects donor site complications. By optimizing this approach, we can enhance breast reconstruction outcomes for challenging low-BMI patients.

4. Discussion

In recent years, the PAP flap has emerged as a suitable alternative to the DIEP flap. Initially utilized when the DIEP flap is not feasible, recent studies [

6,

8,

9,

11,

15] have shown comparable aesthetic and complication rate-related data. Thus, the PAP flap is not just a second-line alternative for patients with limited donor tissue or limiting scars due to prior abdominal surgeries, but a potential option for all patients favoring autologous tissue breast reconstruction. The thigh-based PAP flap is characterized by a long pedicle, continuous blood supply, and favorable scar placement [

26]. At our department, the PAP flap is mainly used in slim patients lacking sufficient abdominal donor tissue. While this subgroup is a frequent indication in our practice, we acknowledge that the PAP flap is also broadly used in patients with adequate abdominal tissue, particularly in cases requiring low-volume reconstruction or when abdominal donor site morbidity is to be avoided. The focus on this subgroup in our study reflects institutional case distribution rather than a general limitation of the PAP flap’s applicability. Originally, we started with the classic horizontal design. However, this presented a major challenge in harvesting enough tissue for lean patients. In such cases, obtaining sufficient volume while preserving optimal contour is technically demanding, requiring precise dissection and careful flap shaping. An additional challenge in slim patients is that the PAP flap is already associated with a higher donor site complication rate [

15]. This risk is further exacerbated by the need to harvest as much tissue as possible, potentially leading to an increased incidence of wound healing issues and contour deformities. To address this, both technical refinements and alternative flap designs have been explored [

7,

14,

19,

20]. Alternative flap designs have proven effective in obtaining more reconstructive tissue and thus offering enough tissue for higher reconstruction volume [

16,

27,

28,

29]. Our department observed a higher rate of wound healing complications up to 29.6% using the PAP flap with the original horizontal skin island design [

11,

14]. This is likely because our PAP flap patients are challenging to treat due to their low BMI. Therefore, we first refined the technique [

14] and then planned the PAP flap as a vertical flap inspired by the work of Rivera-Serrano et al. [

18] and Scagliogni et al. [

19]. The vertical skin island design was introduced at our department by one of the senior authors as part of an institutional effort to optimize donor-site outcomes. While she led the initial application of the vertical design, the procedures were performed as part of the breast reconstruction team and not by a single surgeon in isolation. In bilateral cases, flap harvest was shared with a second surgeon, and the vertical design was gradually taught and implemented beyond the initial surgeon. Therefore, while early vertical cases were predominantly performed by one senior surgeon, the technique’s adoption reflects a broader institutional evaluation rather than individual advocacy. In this study, we present our data on the vertical skin island in comparison to the horizontal skin island and the influence of skin island design on complication rates, patients’ satisfaction, and aesthetic outcome. The two patient groups were matched in terms of age, BMI, mastectomy volume, and flap volume. Also, there is no statistically significant difference concerning chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and smoking status. Although we did not observe a statistically significant difference in smoking status, smoking may still affect wound healing.

We acknowledge that the limited sample size of this study reduces the statistical power to draw definitive conclusions regarding complication rates or long-term aesthetic outcomes. While larger series have been published focusing predominantly on the horizontal PAP flap, direct comparisons between vertical and horizontal skin paddle designs remain rare. To our knowledge, only two published studies to date have investigated this specific comparison with larger patient numbers [

17,

28], and other reports on the vertical PAP flap involve similar or smaller cohorts [

18,

19]. Several large case series have further contributed valuable data on the outcomes of horizontal PAP flap breast reconstruction. Allen et al. reported excellent results with 164 flaps and minimal flap loss [

30]. Haddock and colleagues subsequently presented two extensive series of 101 and 265 flaps, demonstrating low flap loss rates and progressive refinements to reduce complications [

7,

31]. More recently, Tielemans et al. published outcomes of an extended PAP flap design in 46 cases to increase flap volume for larger reconstructions or patients with limited donor tissue [

27]. In this context, our study offers one of the few matched cohort comparisons of vertical versus horizontal designs, providing additional insights into donor site outcomes, patient-reported outcomes (PROMs), and early postoperative complications. We recognize that further prospective studies with larger sample sizes will be necessary to confirm and expand upon these preliminary findings.

In our findings, there were reduced rates of early complications, particularly wound healing, at the donor site when using the vertical skin island design. Although not statistically significant, we noticed this as a positive trend. Scaglioni et al. [

19] and Artz et al. [

20] have reported similar findings in previous studies. We believe that with the vertical skin island, less tension is placed on the scar. At the horizontal incision line, the scar is placed directly in an area with high tension, which tends to result in wound-healing complications. However, the early complication rate in the horizontal group was significantly higher than in the vertical group (

p = 0.06). Our findings suggest that a vertical skin island design may be particularly beneficial in low BMI patients by reducing complication rates.

While the vertical group showed more touch-up procedures, the horizontal group experienced a higher rate of early complications requiring immediate revision. One possible explanation is that the vertical scar does not lie within a natural anatomical fold, which may lead to increased scar visibility or irritation during healing, making it more likely to require secondary revision. In contrast, the horizontal scar is positioned within a natural gluteal crease, which may promote better scar integration and tolerance, even if early complications are more frequent. Therefore, the clinical relevance of each complication type must be considered in context.

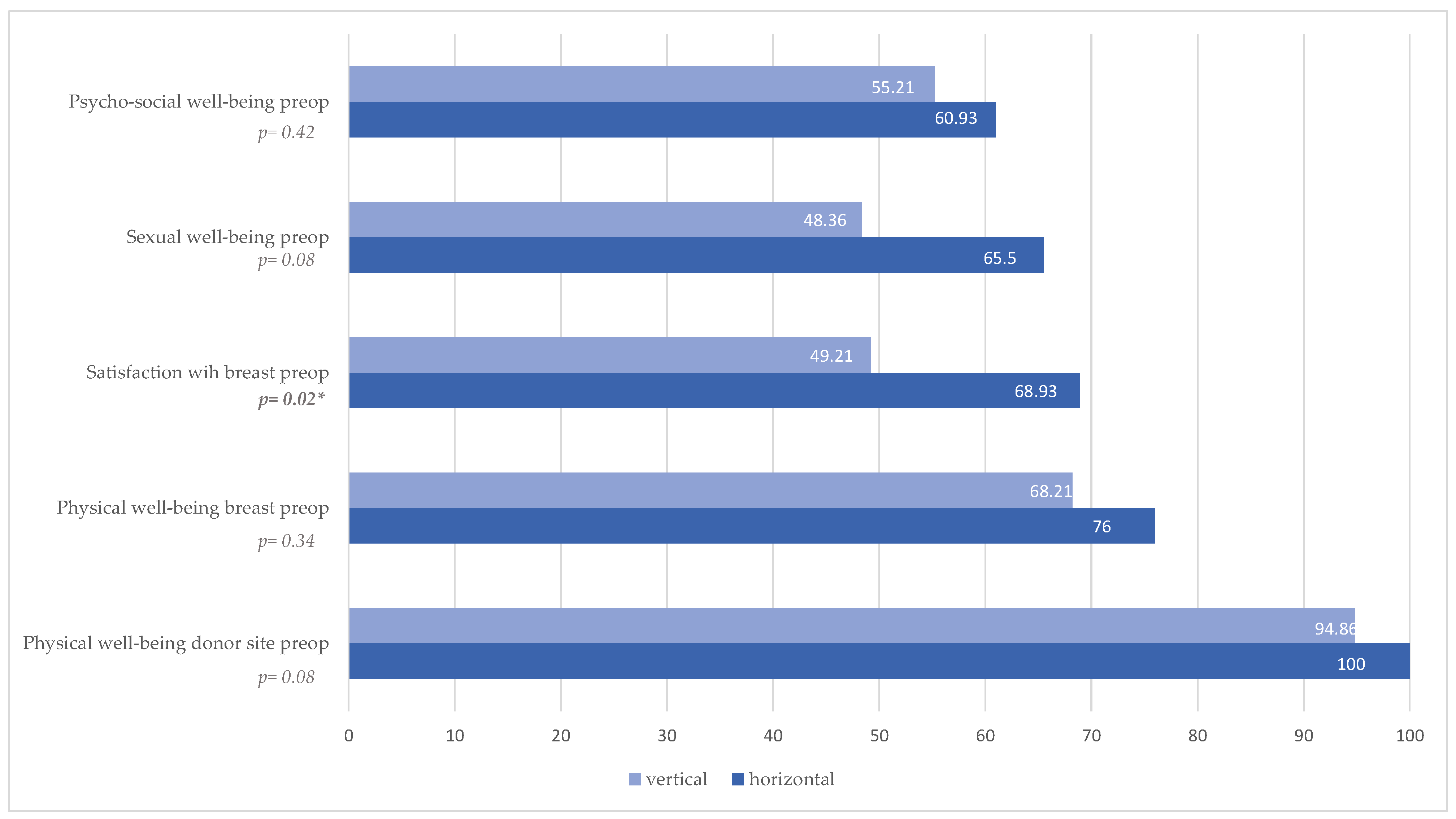

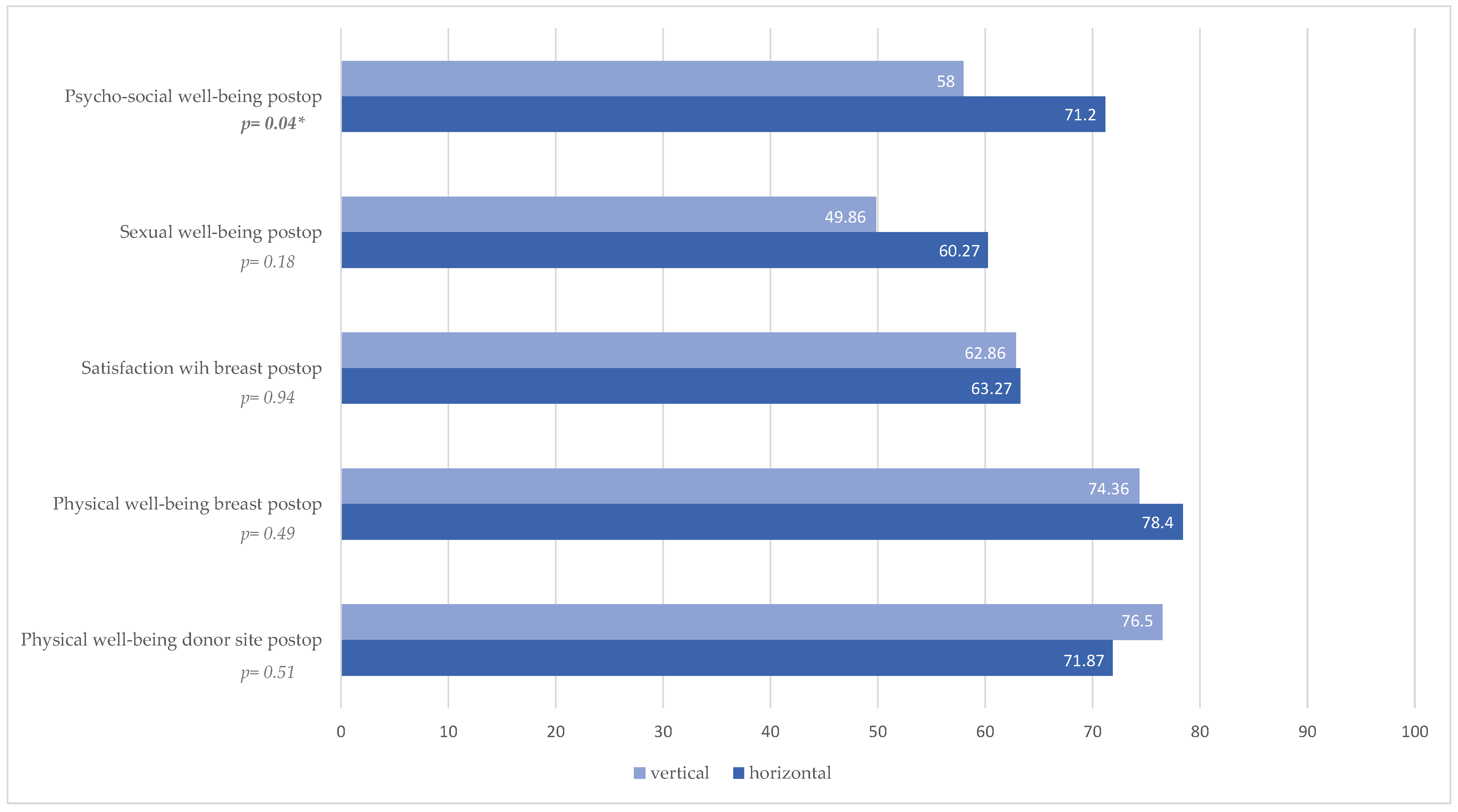

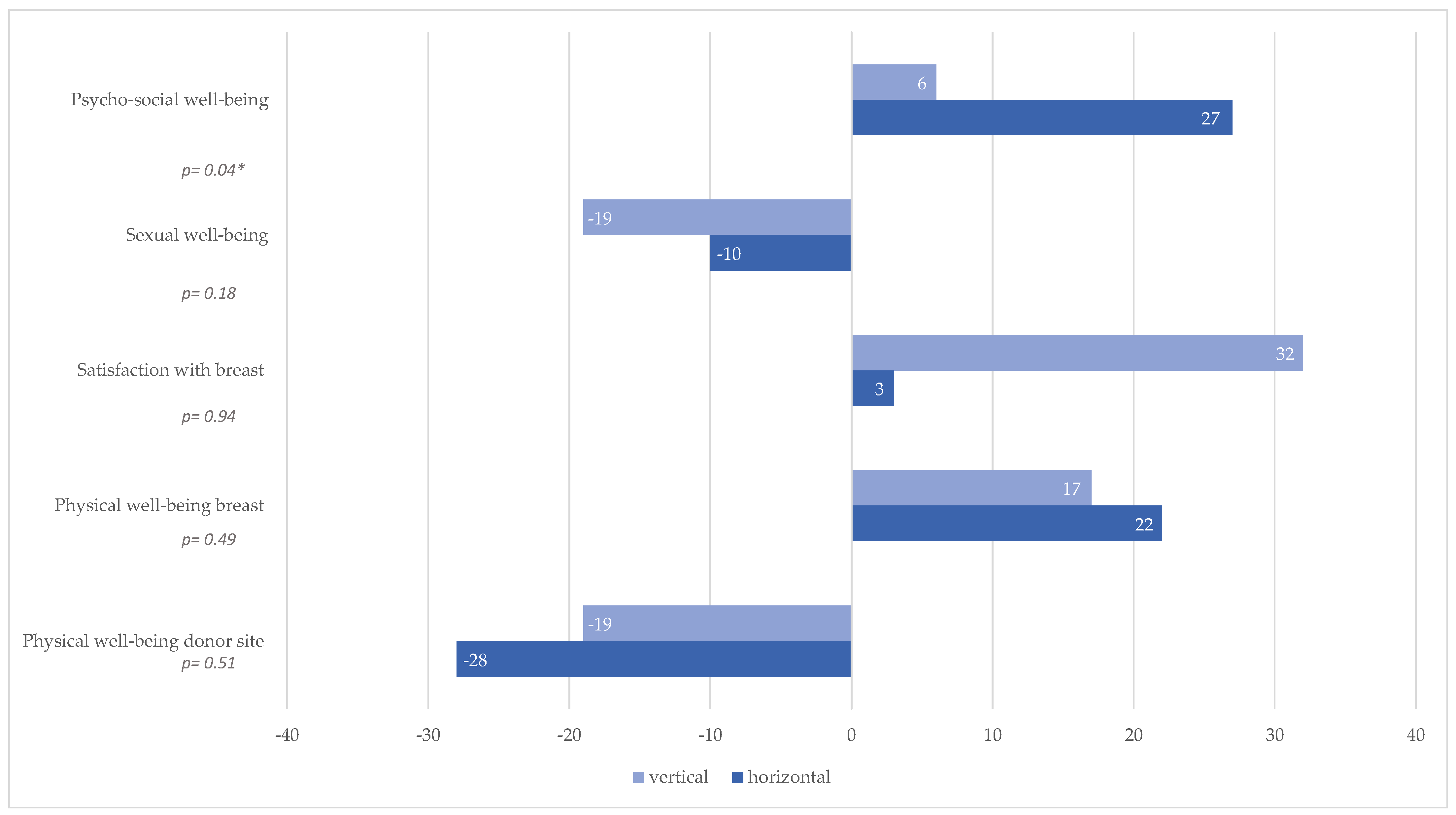

In the postoperative BREAST-Q questionnaire, no significant difference is observed between the two groups (vertical skin island versus horizontal skin island) in all categories except the psychosocial well-being, which is described significantly better in the horizontal group (p = 0.04). A possible explanation for this could be that the patients with vertical skin island design were mainly operated on during the COVID-19 pandemic, which had a negative impact on their psychosocial well-being in general. The horizontal skin island group underwent surgery mainly before the pandemic. However, we noted that both groups were significantly less satisfied with their thigh postoperatively compared to the preoperative results (p = 0.01 in the vertical skin island group versus p < 0.01 in the horizontal skin island group). Although the differences in BREAST-Q scores related to the thigh were not statistically significant, we observed a trend toward lower patient-reported satisfaction in the vertical group across several domains, including the appearance of the thigh when unclothed, the position of the gluteal crease, and scar-related concerns. These findings suggest that, despite potential advantages in scar quality or donor-site tension with the vertical design, the overall perception of thigh aesthetics may be less favorable. This highlights the importance of discussing aesthetic advantages and disadvantages with patients during preoperative counseling, particularly when choosing between skin island designs.

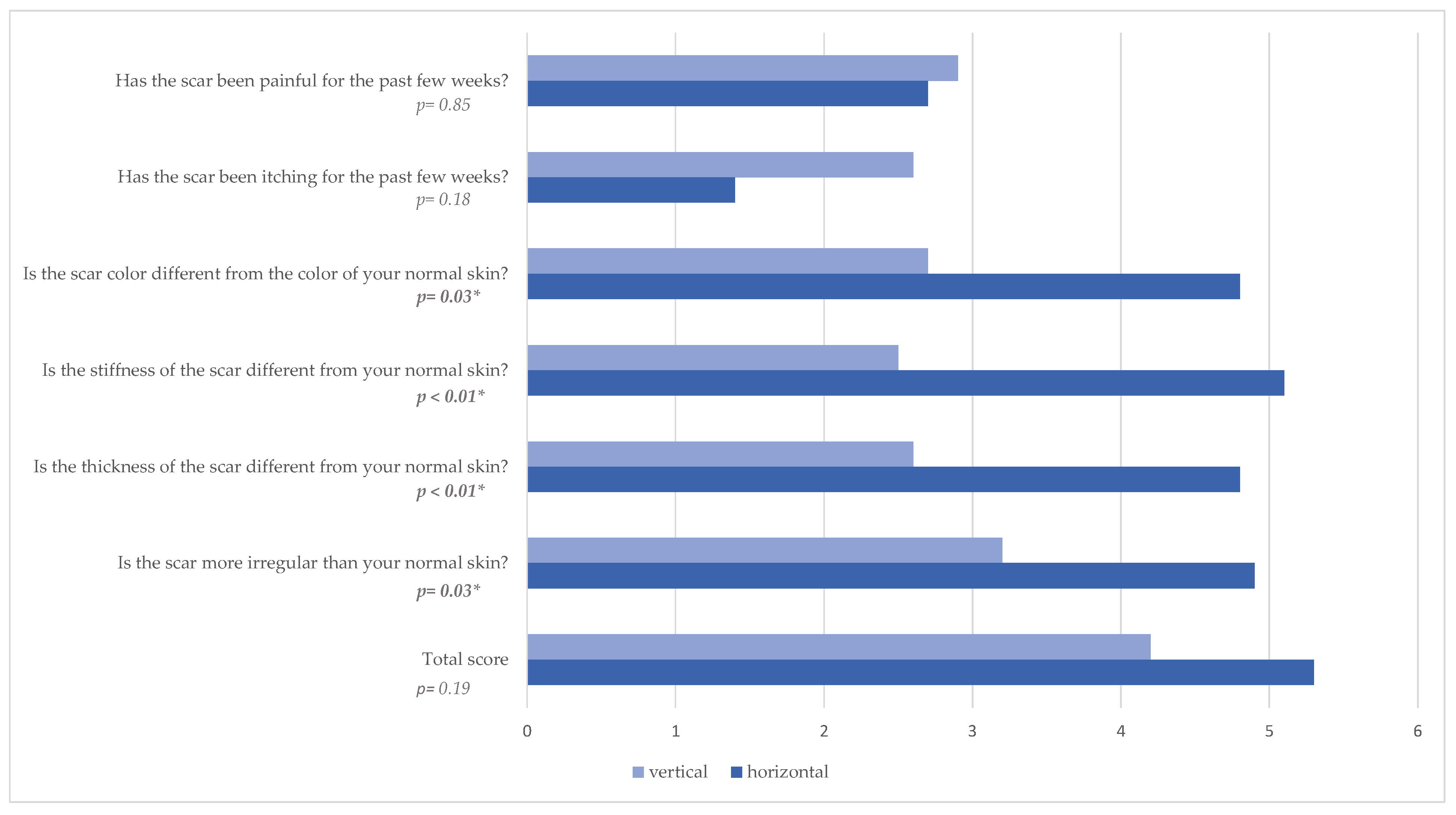

Evaluating the POSAS questionnaire, significantly greater satisfaction was noted both among the observers and the patients in the vertical skin island group. The scar was described as thinner (

p < 0.01), less irregular (

p = 0.03), less pigmented (

p = 0.03), and less stiff (

p < 0.01) from the patients and as less pigmented (

p = 0.03), thinner (

p = 0.02), and with less relief (

p = 0.02) from the observers. We attribute this to the location of the scar, as with the vertical dorsal design, patients themselves see their scars poorly. The horizontal scar is much more visible and bothersome to patients, especially when sitting. Further, we think this result is caused by reduced rates of wound healing complications. Another advantage of the vertical skin island design is a more accessible surgical site. With the vertical skin island design, access to the pedicle is easier, as it eliminates the need to undermine the flap up to the distal thigh, compared to the horizontal skin island. Furthermore, advantages of the vertical skin island design over the horizontal design include reduced rate of wound healing complications at donor site, better access to the pedicle intraoperatively, fewer lymphatic vessel injuries [

19], prevention of widening of the labia majora [

32], and better quality of life for patients according to BREAST-Q. We did not observe that the alternative flap design resulted in a higher flap weight, nor was it our aim to obtain larger flaps with comparable patient demographics.

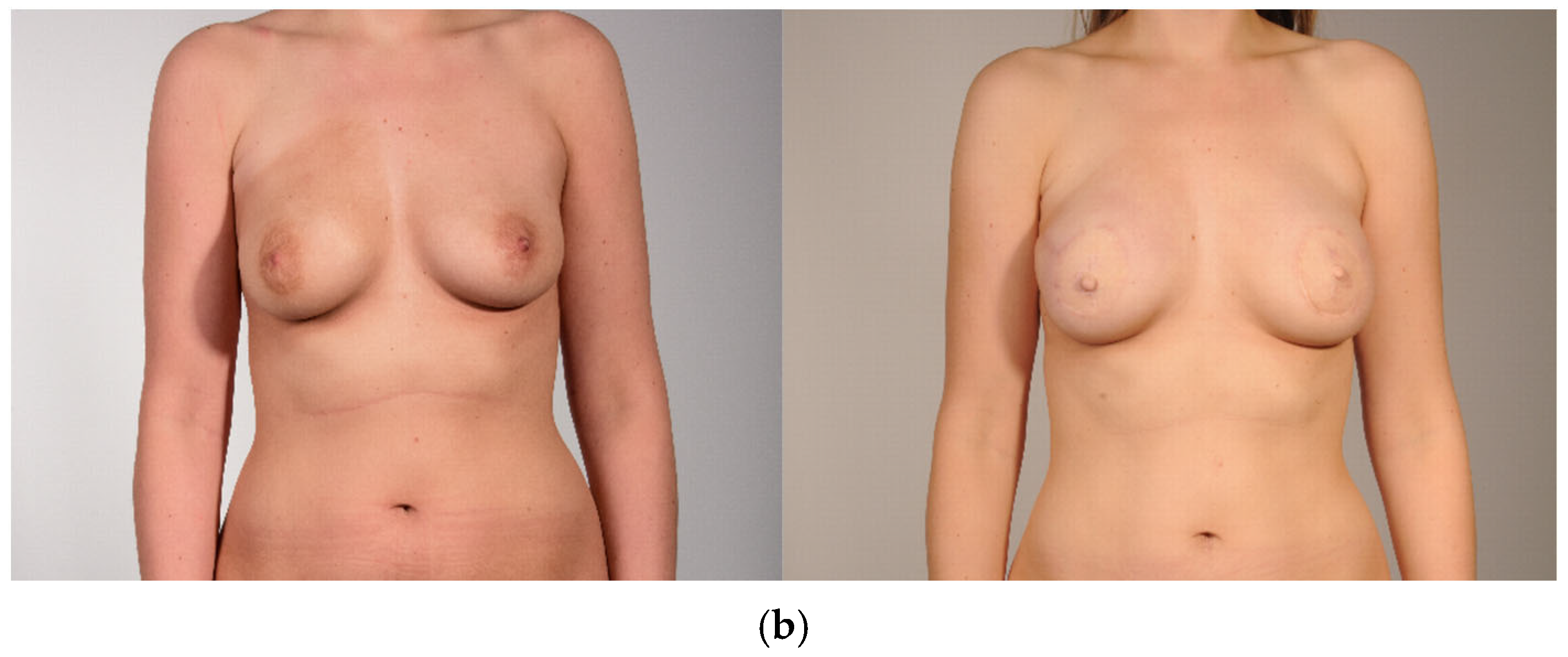

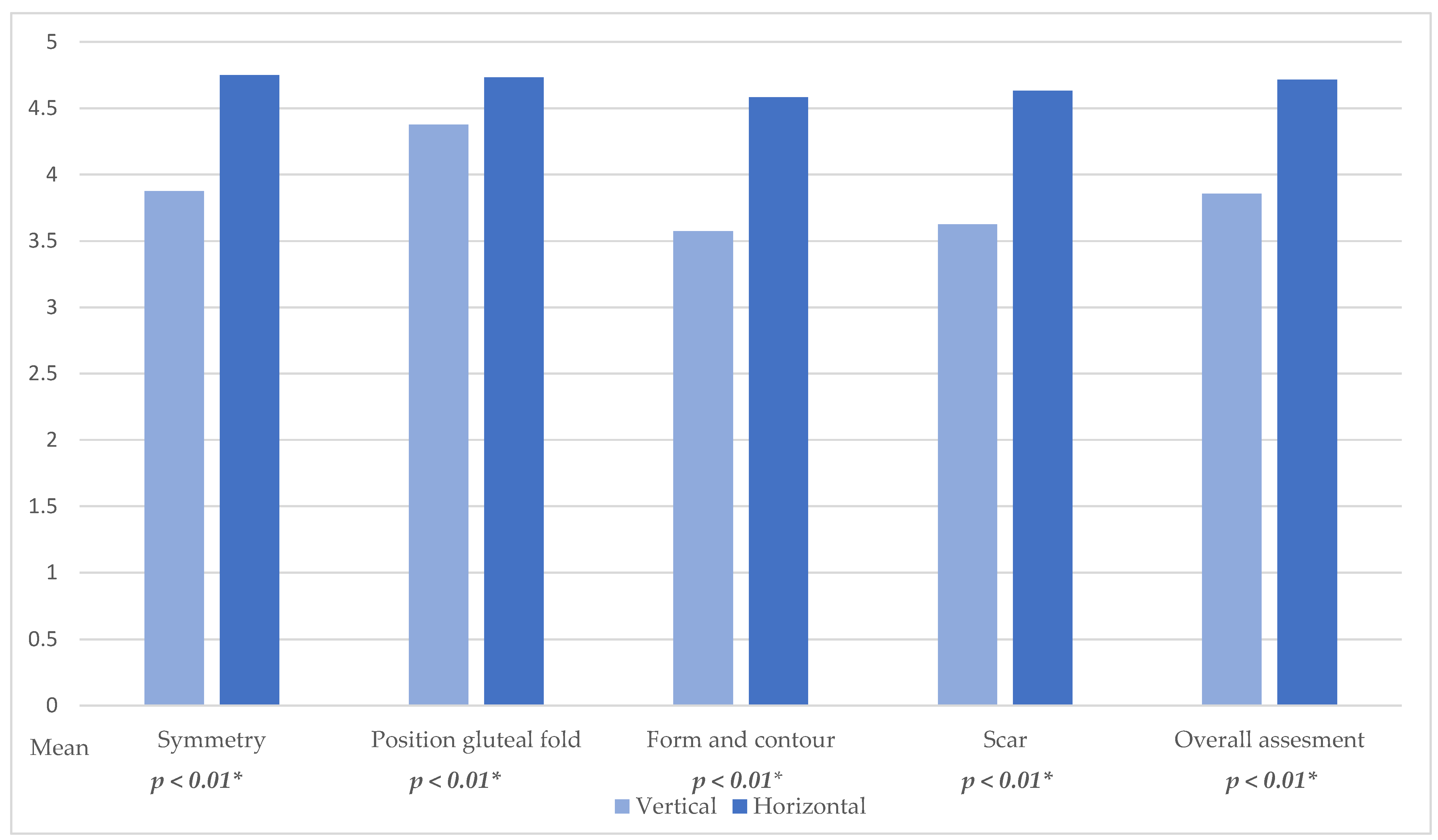

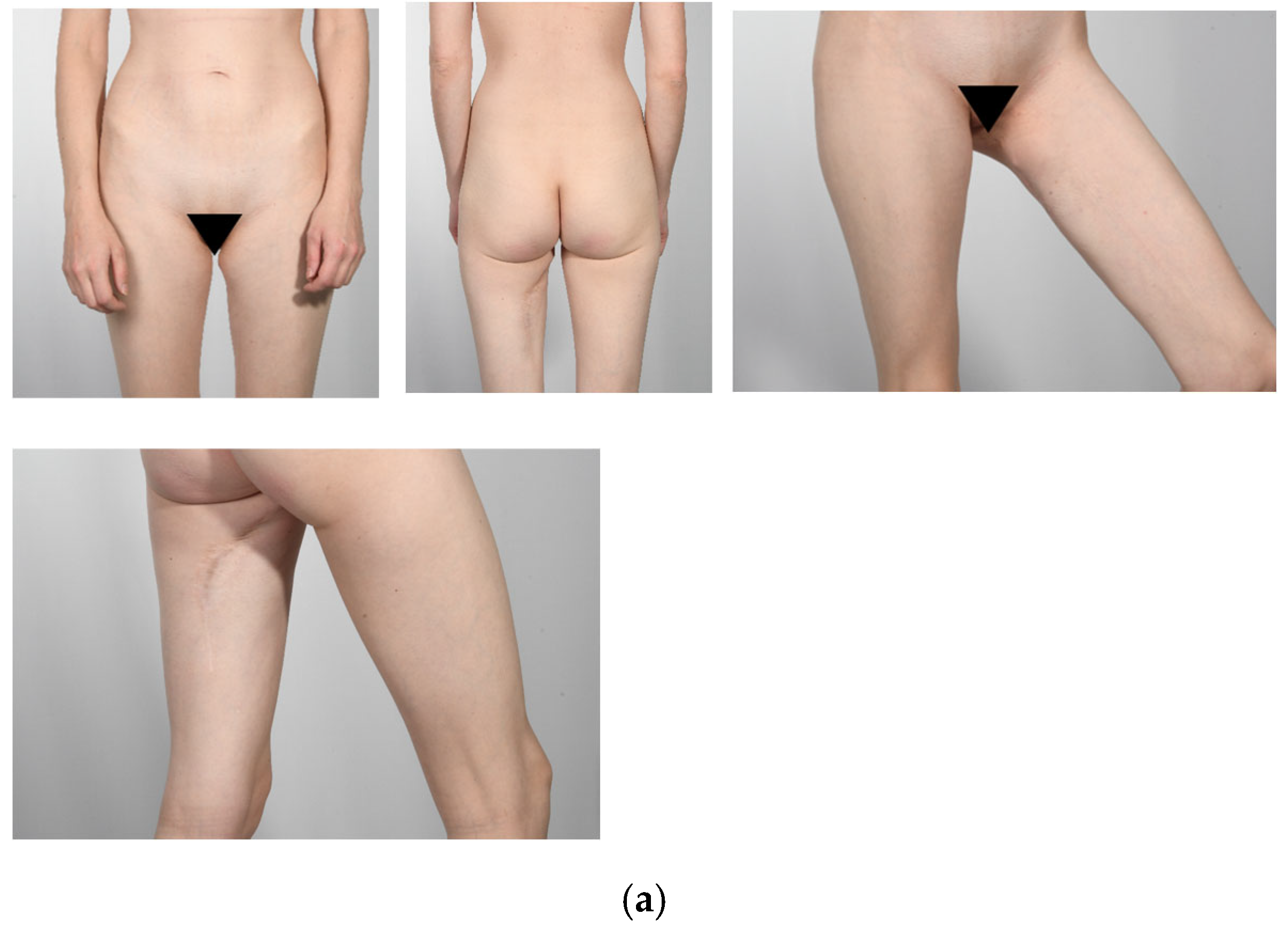

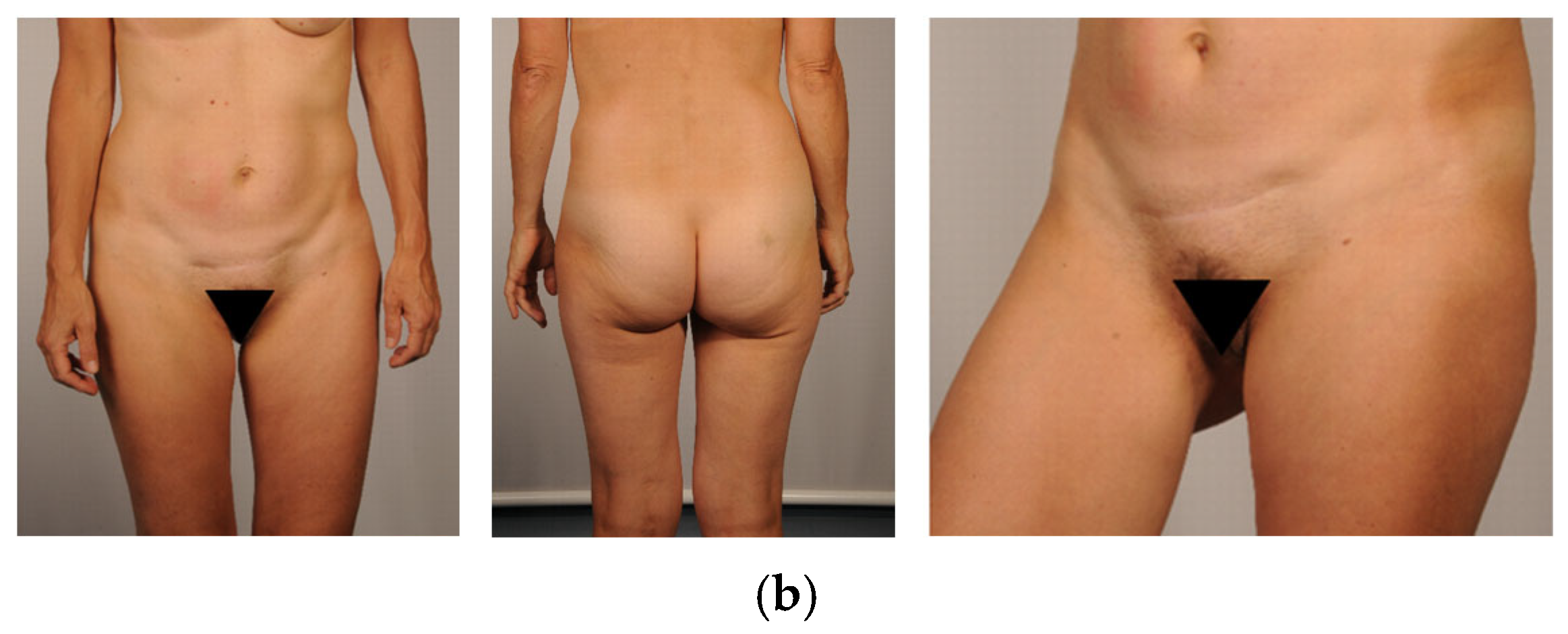

In our aesthetic analysis of the donor site, we found that the horizontal skin island design was superior to the vertical skin paddle in all categories. Particularly in terms of symmetry, the horizontal skin island design showed better results. Initially, we were concerned that the horizontal skin paddle would perform worse regarding symmetry and position of the gluteal fold. However, this concern was not confirmed. Although statistical significance was achieved by only two out of four evaluators for the position of the gluteal fold, a trend is evident. Surprisingly, thigh symmetry was rated better by all four surgeons for the horizontal skin paddle. This may be due to the vertical skin paddle leaving more contour defects than anticipated. The overall assessment of the appearance of the scar from the horizontal skin paddle was rated as superior in aesthetic evaluation by all surgeons, with three out of four showing statistically significant results. Interestingly, although patient-rated POSAS scores indicated better scar characteristics in the vertical group, such as thinner, less pigmented, and more flexible scars, the standardized aesthetic evaluations based on postoperative photographs evaluated by surgeons consistently favored the horizontal design across all measured thigh parameters. This highlights an important point: favorable scar quality alone does not necessarily translate into superior overall aesthetic outcomes. Factors such as scar placement, symmetry, and how well the contour integrates into natural anatomical landmarks appear to significantly influence the aesthetic appearance. These findings demonstrate the need to consider both subjective and objective outcome measures when evaluating donor site design.

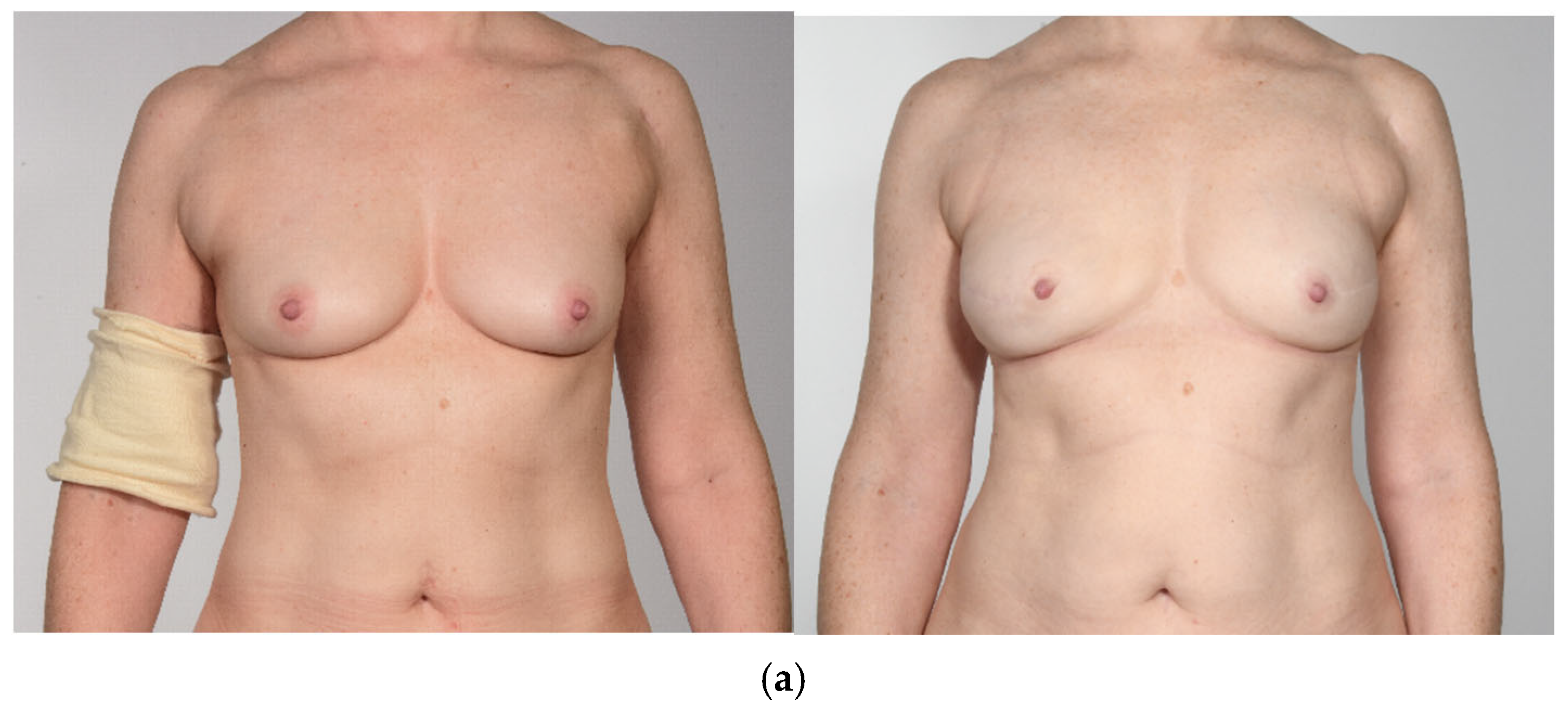

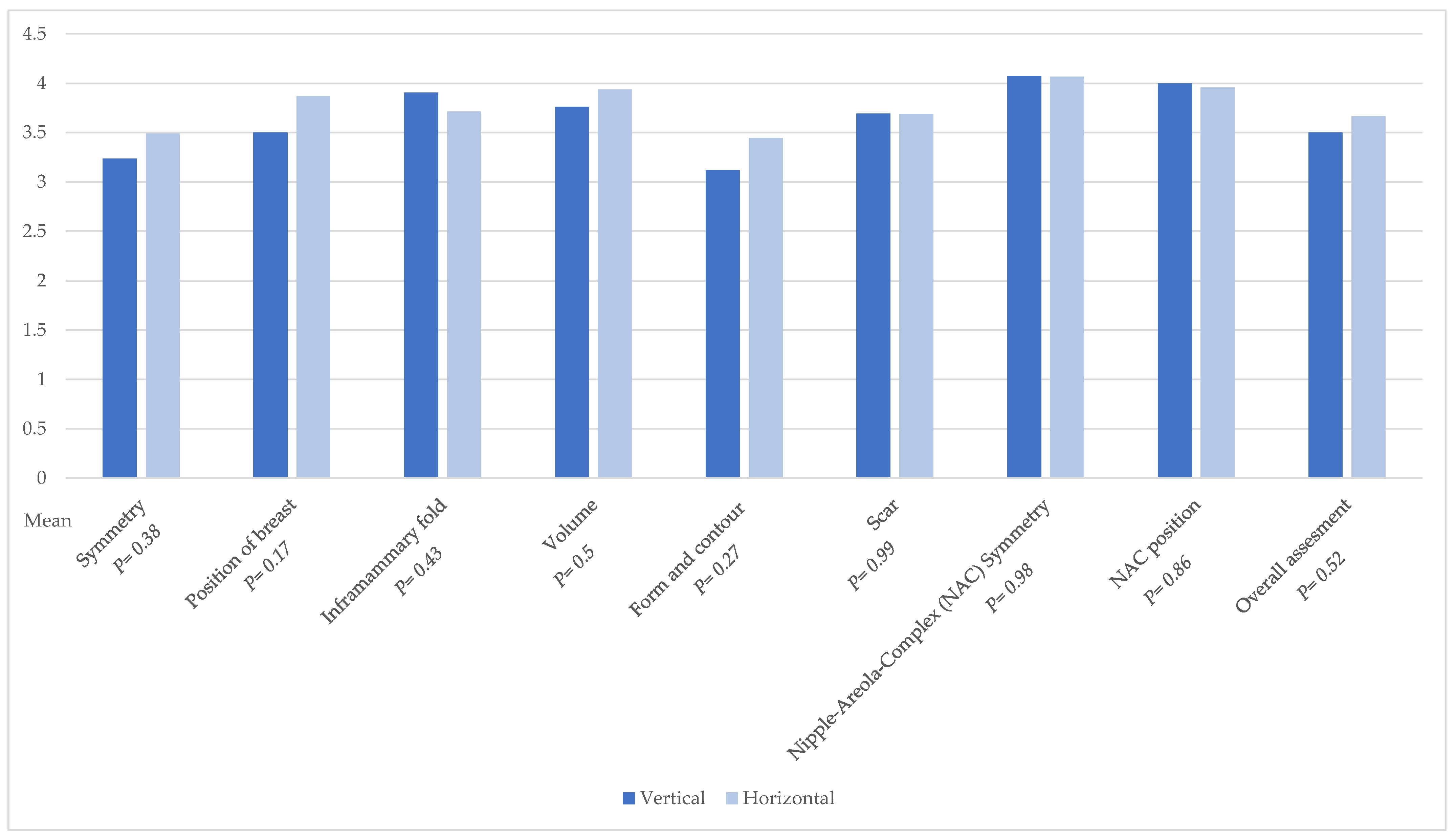

Also, our concern that the vertical design would lead to a more vertically shaped breast was not confirmed. The aesthetic analysis of breasts showed no statistical significance in all categories. It can be concluded that the different skin island designs do not affect breast shape.

Moreover, while our study emphasizes early postoperative outcomes and patient-reported aesthetics, we recognize the importance of long-term follow-up. Future analyses will aim to include outcomes such as sensory changes, donor site morbidity, and the need for secondary revision surgery. Continued follow-up of this cohort is ongoing, and we believe that prospective, larger-scale studies will be essential to further validate and refine our findings.

This study shows the discrepancy between patients’ versus surgeons’ evaluations concerning aesthetic aspects. Therefore, we recommend implementing PROMs in general regarding aesthetic aspects as standardized quality indicators.

As a limitation, we would like to address the single-institution design, which provides insight only into the outcomes from our department. Another limitation is the non-randomized study design. While the horizontal skin island procedures were performed by multiple senior surgeons, the vertical skin island technique was primarily introduced and performed by one senior surgeon during its early implementation phase. However, in bilateral cases, one side was typically performed by a second surgeon, and the vertical design was gradually adopted and taught to other members of the breast reconstruction team. Although this surgeon was also involved in horizontal flap procedures, surgeon-related variability in outcomes cannot be entirely ruled out. Another limitation could be the sample size of the patients; however, a key strength of the study lies in the matching of patients, which ensures homogeneity between the two groups included.