From Fear to Hope: Understanding Preparatory and Anticipatory Grief in Women with Cancer—A Public Health Approach to Integrating Screening, Compassionate Communication, and Psychological Support Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Anticipatory Grief in Loved Ones

3.1.1. Emotional and Psychological Burden

3.1.2. Onset and Trajectory of Grief

Dimensions and Early Onset of Pre-Death Grief

3.1.3. Impact on Decision-Making

3.2. Preparatory Grief in Cancer Patients

3.2.1. Existential and Emotional Processing

3.2.2. Spiritual and Identity Challenges

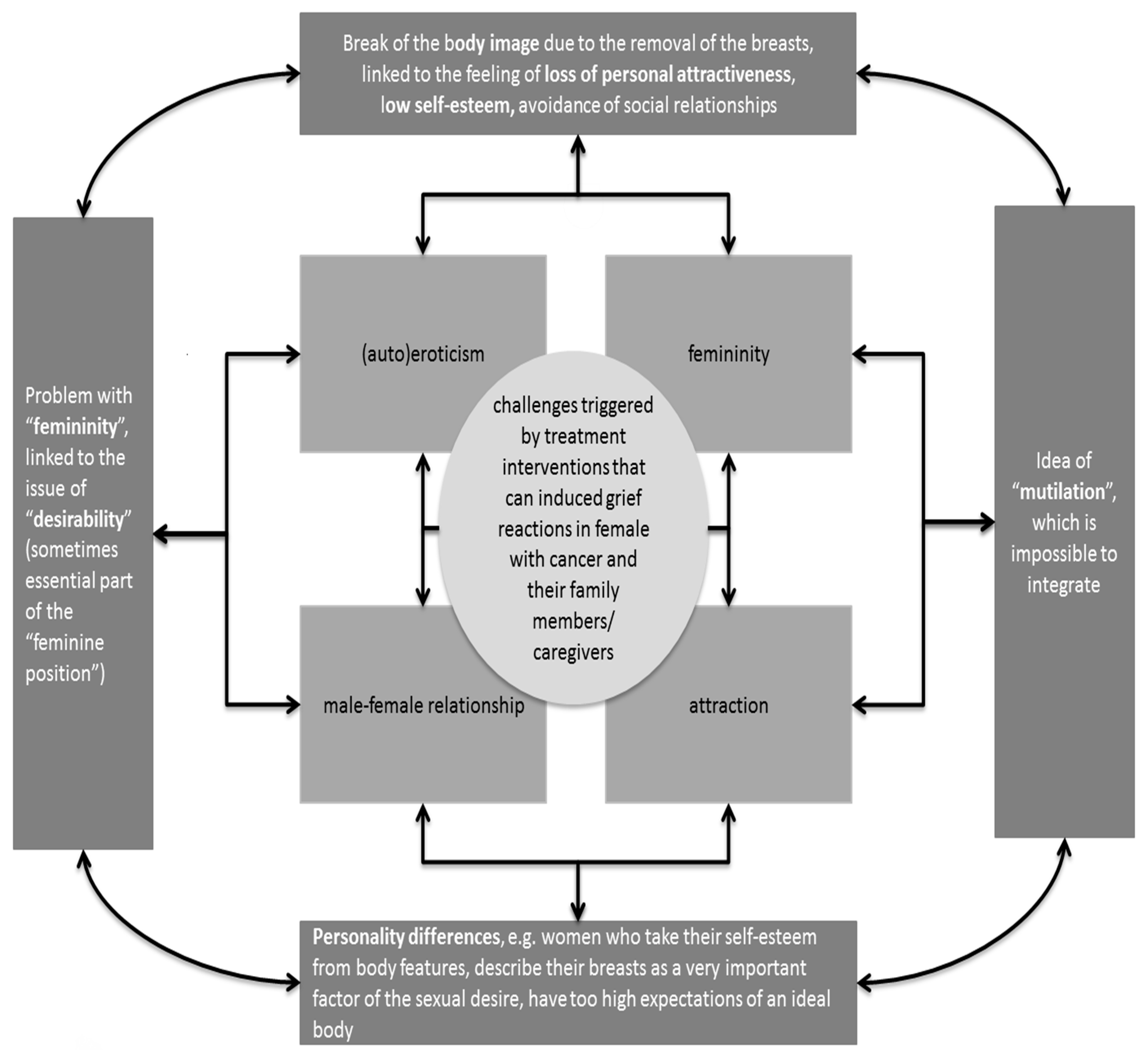

3.2.3. Body Image and Loss of Autonomy

3.3. Stress Responses in Grief

3.3.1. Physiological Stress Markers

3.3.2. Trauma-like Symptoms

3.3.3. Influencing Factors on Stress Regulation

3.4. Effectiveness of Psychotherapeutic Interventions

3.4.1. Types of Effective Therapies

3.4.2. Family-Based and Narrative Approaches

3.4.3. Timing and Impact

3.5. Role of Social Support and Coping Strategies

3.5.1. Community and Peer Support

3.5.2. Coping Styles and Gender Variance

3.5.3. Cultural Norms and Caregiving Role Expectations

3.6. Gender Differences in Grief Response

Emotional Expression vs. Avoidance

4. Discussion

4.1. The Multifaceted Nature of Grief in the Cancer Journey

4.2. The Growing Burden of Cancer: A Global and National Perspective

4.3. Screening as a Clinical and Emotional Intervention

4.4. The Role of Education in Managing Grief Communication

4.5. Understanding the Psychological Impact of Cancer on Women: Coping, Distress, and Adaptation

4.6. Unseen Grief: What Clinicians Are Missing in Addressing Anticipatory and Preparatory Grief in Cancer Care

4.7. How to Integrate Psychotherapy in Terminally Ill Cancer Patients and Their Families Every Day

4.8. Future Research Directions: Early Intervention and Psychotherapy Efficacy in Preparatory and Anticipatory Grief

4.9. Protective Factors and Systemic Support in Preparatory and Anticipatory Grief

4.10. Predicting Long-Term Psychological Outcomes in Preparatory and Anticipatory Grief

4.11. Healthcare System Implications and Public Health Policy for Supporting Women with Cancer and Their Loved Ones Through Targeted Psychotherapy and Other Interventions Against Preparatory and Anticipatory Grief

4.12. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PICO | Patient/population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome |

| DALYs | Disability-adjusted life years |

| YLDs | years lived with a disability |

| PAP | Papanicolaou test |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease of 2019 |

Appendix A

| Term | Source | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Bereavement | Shear, 2012 [81] | The psychological process and experience of letting go. |

| Grief | Shear, 2012 [81] | The reaction to bereavement, with an impact on feelings, thoughts, behaviors and physiological changes (varying in pattern and intensity over time). This is a highly unique and individual process. |

| Mourning | Shear, 2012 [81] | The process of integrating the consequences and finality of the loss into the memory system. |

| Complicated grief | Shear, 2012 [81] | Departure from the uncomplicated grief patterns with interruptions in the daily occupations due to the grief. Symptoms can include:

|

| Anticipatory/preparatory grief | Fulton, 1980 [87] | The preparation for a prospective loss and a response to a loss of meaning and having to adjust the personal purpose and meaning in the own life. Characteristics:

|

| Questions Providing Guidance for Healthcare Professionals in Communicating with Terminally Ill Patients and Their Family Members/Caregivers | Multinational and Multi-Religious Perspectives on End-of-Life |

|---|---|

| Who should the doctor talk to first when discussing the test results or diagnosis? | In some cultures, the family members may have a greater say in decision making than the patient. It is important to respect and acknowledge family dynamics. |

| What are the cultural rituals for coping with dying person? | It is important for healthcare professionals to know how to address caregivers/family members and to what extent to share information regarding the status of the patient with each member of family/caregiver system. |

| What does the family consider to be the roles of each family member in handling the dying patient and death? | This is important in order to detect the best way of how to include the social support network. |

| What are the cultural rituals for handling the deceased person’s body? | In some religions, such as Buddhism, the body should not be touched for 3–8 h after breathing ceases as the spirit lingers on for some time. Furthermore, Hindus believe the body of the dead must be bathed, massaged in oils, dressed in new clothes, and then cremated before the next sunrise. |

| What are the final arrangements for the body and honouring the death? | It is important for any medical institution to facilitate the funeral procedures and support the family/caregivers by decreasing the burden of the painful organizational process. |

| What are the family’s beliefs about what happens after death? | Some religions cope with death and dying more easily, e.g., both Muslims and Christians believe in an afterlife and view the earthly life more in terms of preparing for an eternal life. In the Jewish tradition, the focus is on the purpose of an earthly life, which is to fulfil one’s duties to god and one’s fellow men. This may introduce difference in grieving intensity. |

| Are certain types of dying/death less acceptable for certain religions? | Consider for example suicide, euthanasia or palliative sedation. |

| Is organ donation allowed within the patient’s religion? | This is important, because some religion do not agree with organ donation. |

| What is the preferred manner of the funeral within the patients religion? | In case the patient does not have anyone and needs to be taken care of by a medical institution after the death, it is important to be aware of the fact that some religions favour cremation over burial. |

| Preparatory and Anticipatory Grief Psychotherapy | How It Helps the Individual with Cancer | How It Helps the Patient’s Loved Ones | How It Helps Clinical Healing and/or Clinician |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Processing | Helps patients confront and articulate their fears, reducing emotional distress. | Assists family members in understanding the patient’s emotions and responding empathetically. | Enhances the therapeutic alliance and improves communication between clinicians and patients. |

| Coping Strategies | Provides patients with effective coping mechanisms to manage grief and stress. | Empowers loved ones with strategies to support the patient and manage their own emotions. | Reduces the likelihood of burnout by equipping patients and families with practical coping tools. |

| Family Involvement | Engages family members in the care process, improving patient support. | Facilitates family cohesion and understanding, which can alleviate relational stress. | Strengthens the support network around the patient, contributing to a more comprehensive care approach. |

| Preparation for Future Loss | Allows patients to make practical and emotional preparations, providing a sense of control. | Helps loved ones anticipate and prepare for future grief, potentially reducing their emotional burden. | Aids clinicians in managing end-of-life care more effectively by aligning patient and family expectations. |

| Reduced Emotional Distress | Leads to decreased levels of anxiety and depression related to the diagnosis. | Mitigates secondary stress and anticipatory grief experienced by family members. | Supports clinicians in providing effective care without being overwhelmed by the emotional complexity of the case. |

| Aspect | Anticipatory Grief | Preparatory Grief |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Grief experienced by individuals expecting to lose a loved one (pre-loss) | Grief experienced by individuals nearing the end of their own life (post-loss preparations) |

| Who Experiences It | Family members, caregivers, and loved ones of someone with a terminal illness | The person who is terminally ill, as they prepare for their own death |

| Emotional Response | Feelings of sadness, fear, anxiety, and uncertainty about the impending loss | Feelings of sadness, existential anxiety, mortality awareness, and emotional distress related to one’s own death |

| Focus | Focus on the upcoming loss of a loved one and emotional preparedness | Focus on self-reflection, the impact on loved ones, and managing end-of-life issues |

| Common Symptoms | Anxiety, depression, anticipatory grief symptoms, heightened emotional distress | Sadness, fear, anger, acceptance, spiritual concerns, and emotional withdrawal |

| Coping Strategies | Emotional regulation, preparing for life without the loved one, practical planning | Reflection on life, closure, legacy-building, preparing loved ones emotionally and practically |

| Impact on Quality of Life | Can negatively affect well-being due to ongoing emotional strain and uncertainty | Can reduce quality of life by focusing on mortality and what’s to come |

| Psychotherapeutic Interventions | Counseling, therapy focusing on emotional expression and practical preparation for the loss | Supportive therapy focusing on life review, existential concerns, emotional support for family, and closure |

| Illness Representations | Patients and families may struggle with understanding the illness trajectory, leading to greater uncertainty and distress | Patients who have a clear understanding of their illness may engage in more active preparations, while those with misconceptions or denial may experience more prolonged emotional distress |

| Coping Influence by Illness Representation | Illness representations, such as viewing the illness as uncontrollable or as a threat, often lead to heightened emotional distress and avoidance behaviors in coping | A more accurate or accepted illness representation may help in managing anticipatory grief by fostering acceptance and active preparation for death, but denial or unrealistic expectations can increase distress |

| Gender Differences | Women may experience greater emotional intensity, leading to increased vulnerability to anticipatory grief | Women may be more likely to focus on relationships and caregiving aspects, leading to more emotional and social preparation for their death |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2133–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; Australian Government Department of Health. Analysis of colorectal cancer outcomes for the Australian National Bowel Cancer Screening Program. Asia-Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 12, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzi, M.; Urso, E.D.L. Impact of colorectal cancer screening on incidence, mortality and surgery rates: Evidences from programs based on the fecal immunochemical test in Italy. Dig. Liver Dis. 2023, 55, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massat, N.J.; Dibden, A.; Parmar, D.; Cuzick, J.; Sasieni, P.D.; Duffy, S.W. Impact of Screening on Breast Cancer Mortality: The UK Program 20 Years On. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2016, 25, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthmuller, S.; Carrieri, V.; Wübker, A. Effects of organized screening programs on breast cancer screening, incidence, and mortality in Europe. J. Health Econ. 2023, 92, 102803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živković Perišić, S.; Miljuš, D.; Jovanović, V. Registracija malignih bolesti u proceni opterećenosti društva rakom. Glas. Javnog Zdr. 2021, 95, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulić, M.; Milosavljević, M.; Jovanović, V. Značaj sprovođenja promotivnih aktivnosti putem sredstava javnog informisanja u prevenciji raka grlića materice. Glas. Javnog Zdr. 2025, 99, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, E.A.; Silver, M.I.; Kobrin, S.C.; Marcus, P.M.; Ferrer, R.A. Cancer screening: Health impact, prevalence, correlates, and interventions. Psychol. Health 2019, 34, 1036–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimori, M.; Uchitomi, Y. Preferences of cancer patients regarding communication of bad news: A systematic literature review. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 39, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.; de Brito, M.; Teixeira, P.; Frade, P.; Barros, L.; Barbosa, A. Family Caregivers’ Anticipatory Grief: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Its Multiple Challenges. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikstrom, L.; Saikaly, R.; Ferguson, G.; Mosher, P.J.; Bonato, S.; Soklaridis, S. Being there: A scoping review of grief support training in medical education. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esplen, M.J.; Wong, J.; Vachon, M.L.S.; Leung, Y. A Continuing Educational Program Supporting Health Professionals to Manage Grief and Loss. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute of U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: http://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms?CdrID=46053 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- National Cancer Institute of U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Al-Gamal, E. Quality of life and anticipatory grieving among parents living with a child with cerebral palsy. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2013, 19, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shear, M.K.; Ghesquiere, A.; Glickman, K. Bereavement and complicated grief. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2013, 15, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. Available online: https://publications.iarc.fr/Databases/Iarc-Cancerbases/GLOBOCAN-2012-Estimated-Cancer-Incidence-Mortality-And-Prevalence-Worldwide-In-2012-V1.0-2012 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Cancer Research UK (UK CR). Worldwide Cancer Incidence 2012. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/worldwide-cancer/incidence#ref-1 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Dorak, M.T.; Karpuzoglu, E. Gender differences in cancer susceptibility: An inadequately addressed issue. Front. Genet. 2012, 3, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 524–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, Y.L.; Kyrgiou, M.; Bryant, A.; Everett, T.; Dickinson, H.O. Centralisation of services for gynaecological cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 3, CD007945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-M.; Chen, H.-C.; Chen, C.-L.; You, S.-L.; Cheng, W.-F.; Chen, C.-A.; Lee, T.-C.; Chen, C.-J. A prospective study of gynecological cancer risk in relation to adiposity factors: Cumulative incidence and association with plasma adipokine levels. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Su, Y.; Zeng, J.; Chong, W.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, X. Cancer-specific survival after diagnosis in men versus women: A pan-cancer analysis. MedComm 2022, 3, e145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.F.; Kroenke, K.; Theobald, D.E.; Wu, J.; Tu, W. The association of depression and anxiety with health-related quality of life in cancer patients with depression and/or pain. Psycho-Oncology 2010, 19, 734–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, D.; Kiely, M.; Smith, A.; Velikova, G.; House, A.; Selby, P. Anxiety disorders in cancer patients: Their nature, associations, and relation to quality of life. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 3137–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra Pérez, H.C.; Direk, N.; Milic, J.; Ikram, M.A.; Hofman, A.; Tiemeier, H. The Impact of Complicated Grief on Diurnal Cortisol Levels Two Years After Loss: A Population-Based Study. Psychosom. Med. 2017, 79, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, K.G.; Milic, J.; Zaciragic, A.; Wen, K.; Jaspers, L.; Nano, J.; Dhana, K.; Bramer, W.M.; Kraja, B.; Van Beeck, E.; et al. The functions of estrogen receptor beta in the female brain: A systematic review. Maturitas 2016, 93, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaider, T.; Kissane, D. The assessment and management of family distress during palliative care. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2009, 3, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arantzamendi, M.; Sapeta, P.; Belar, A.; Centeno, C. How palliative care professionals develop coping competence through their career: A grounded theory. Palliat. Med. 2024, 38, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, J.; Roberts, K.E.; McLean, E.; Fadalla, C.; Coats, T.; Rogers, M.; Wilson, M.K.; Godwin, K.; Lichtenthal, W.G. An examination and proposed definitions of family members’ grief prior to the death of individuals with a life-limiting illness: A systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2022, 36, 581–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, M.P.; Schuler, T.A.; Kissane, D.W. Family focused grief therapy: A versatile intervention in palliative care and bereavement. Bereave Care 2013, 32, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szuhany, K.L.; Malgaroli, M.; Miron, C.D.; Simon, N.M. Prolonged Grief Disorder: Course, Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment. Focus 2021, 19, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, J.T.K.; Au, D.; Ip, A.H.F.; Chan, J.; Ng, K.; Cheung, L.; Yuen, J.; Hui, E.; Lee, J.; Lo, R.; et al. Barriers to advance care planning: A qualitative study of seriously ill Chinese patients and their families. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergo, M.T.; Whyman, J.; Li, Z.; Kestel, J.; James, S.L.; Rector, C.; Salsman, J.M. Assessing Preparatory Grief in Advanced Cancer Patients as an Independent Predictor of Distress in an American Population. J. Palliat. Med. 2017, 20, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, P. Spirituality, religion and palliative care. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2014, 3, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, A.P.; Martins, H.; Pinto, S.; Caldeira, S.; Pontífice Sousa, P.; Rodgers, B. Spiritual comfort, spiritual support, and spiritual care: A simultaneous concept analysis. Nurs. Forum 2022, 57, 1559–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Guo, Q.; Chen, Z.; Zeng, Y. Dignity therapy, psycho-spiritual well-being and quality of life in the terminally ill: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2023, 13, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopf, D.; Eckstein, M.; Aguilar-Raab, C.; Warth, M.; Ditzen, B. Neuroendocrine mechanisms of grief and bereavement: A systematic review and implications for future interventions. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2020, 32, e12887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltman, S.; Bonanno, G.A. Trauma and bereavement: Examining the impact of sudden and violent deaths. J. Anxiety Disord. 2003, 17, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiderman, N.; Ironson, G.; Siegel, S.D. Stress and health: Psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 1, 607–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.T.; Holmes, S.E.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Esterlis, I. Neurobiology of Chronic Stress-Related Psychiatric Disorders: Evidence from Molecular Imaging Studies. Chronic Stress 2017, 1, 2470547017710916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhney, F.S.; Miklowitz, D.J.; Schiffman, J.; Mittal, V.A. Family-Based Psychosocial Interventions for Severe Mental Illness: Social Barriers and Policy Implications. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2023, 10, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Lee, E.K.P.; Mak, E.C.W.; Ho, C.Y.; Wong, S.Y.S. Mindfulness-based interventions: An overall review. Br. Med. Bull. 2021, 138, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, M.; Kirpekar, V.; Loganathan, S. Family Interventions: Basic Principles and Techniques. Indian J. Psychiatry 2020, 62 (Suppl. S2), S192–S200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pun, J.; Chow, J.C.H.; Fok, L.; Cheung, K.M. Role of patients’ family members in end-of-life communication: An integrative review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nota, P.M.; Bahji, A.; Groll, D.; Carleton, R.N.; Anderson, G.S. Proactive psychological programs designed to mitigate posttraumatic stress injuries among at-risk workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, J.; Drogin, E.Y.; Gutheil, T.G. Treatment delayed is treatment denied. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law Online 2018, 46, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, A.; Kirst, M. The Experiences of Virtual Support for Grief and Bereavement. Illn. Crisis Loss 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundorff, M.; Bonanno, G.A.; Johannsen, M.; O’Connor, M. Are there gender differences in prolonged grief trajectories? A registry-sampled cohort study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 129, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.M.; Tyrka, A.R.; Price, L.H.; Carpenter, L.L. Sex differences in the use of coping strategies: Predictors of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Depress. Anxiety 2008, 25, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Chakrabarti, S.; Grover, S. Gender differences in caregiving among family—Caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World J. Psychiatry 2016, 6, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebe, M.; Stroebe, W.; Schut, H. Gender Differences in Adjustment to Bereavement: An Empirical and Theoretical Review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givon, E.; Berkovich, R.; Oz-Cohen, E.; Rubinstein, K.; Singer-Landau, E.; Udelsman-Danieli, G.; Meiran, N. Are women truly “more emotional” than men? Sex differences in an indirect model-based measure of emotional feelings. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 32469–32482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pătrașcu, C.; Oroian, B.A.; Soveja, A.; Marusic, R.I.; Cozmin, M.; Crețu, O.; Nechita, P. Gender differences in depression: Symptoms, causes and treatments. Bull. Integr. Psychiatry 2024, 100, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellemers, N. Gender stereotypes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2018, 69, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chad-Friedman, E.; Coleman, S.; Traeger, L.N.; Pirl, W.F.; Goldman, R.; Atlas, S.J.; Park, E.R. Psychological distress associated with cancer screening: A systematic review. Cancer 2017, 123, 3882–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasdenteufel, M.; Quintard, B. Psychosocial factors affecting the bereavement experience of relatives of palliative-stage cancer patients: A systematic review. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Jawahri, A.; Greer, J.A.; Park, E.R.; Jackson, V.A.; Kamdar, M.; Rinaldi, S.P.; Gallagher, E.R.; Jagielo, A.D.; Topping, C.E.W.; Elyze, M.; et al. Psychological Distress in Bereaved Caregivers of Patients with Advanced Cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 61, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djordjevic, S.; Boricic, K.; Radovanovic, S.; Simic Vukomanovic, I.; Mihaljevic, O.; Jovanovic, V. Demographic and socioeconomic factors associated with cervical cancer screening among women in Serbia. Front. Public Health 2024, 11, 1275354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjević, S.; Dimitrijev, I.; Boričić, K.; Radovanović, S.; Vukomanović, I.S.; Mihaljević, O.; Jovanović, S.; Randjelović, N.; Lacković, A.; Knezević, S.; et al. Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Breast Cancer Screening among Women in Serbia, National Health Survey. Iran. J. Public Health 2024, 53, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.E.; Lopez, L.M.; Marteau, T.M. Emotional impact of screening: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, J.; Cullen, S.; Casey, B.; Lloyd, B.; Sheehy, L.; Brosnan, M.; Barry, T.; McMahon, A.; Coughlan, B. Bereavement care education and training in clinical practice: Supporting the development of confidence in student midwives. Midwifery 2018, 66, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shear, M.K.; Muldberg, S.; Periyakoil, V. Supporting patients who are bereaved. BMJ 2017, 358, j2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Coping theory and research: Past, present, and future. Psychosom. Med. 1993, 55, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, C.W.; Moorey, S. Outlook and adaptation in advanced cancer: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology 2010, 19, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deimling, G.T.; Wagner, L.J.; Bowman, K.F.; Sterns, S.; Kercher, K.; Kahana, B. Coping among older-adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 2006, 15, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, B.; Clarke, V. The psychological impact of a cancer diagnosis on families: The influence of family functioning and patients’ illness characteristics on depression and anxiety. Psycho-Oncology 2004, 13, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, S.; Das-Munshi, J.; Brahler, E. Prevalence of mental health conditions in cancer patients in acute care: A meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2010, 21, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, A.L.; Danoff-Burg, S.; Huggins, M.E. The first year after breast cancer diagnosis: Hope and coping strategies as predictors of adjustment. Psycho-Oncology 2002, 11, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvillemo, P.; Branstrom, R. Coping with breast cancer: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mystakidou, K.; Tsilika, E.; Parpa, E.; Katsouda, E.; Sakkas, P.; Galanos, A.; Vlahos, L. Demographic and clinical predictors of preparatory grief in a sample of advanced cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 2006, 15, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, S.; Adams, K.B. Grief reactions and depression in caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease: Results from a pilot study in an urban setting. Health Soc. Work 2005, 30, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, A.L.; Snider, P.R. Coping with a breast cancer diagnosis: A prospective study. Health Psychol. 1993, 12, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hack, T.F.; Degner, L.F. Coping responses following breast cancer diagnosis predict psychological adjustment three years later. Psycho-Oncology 2004, 13, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolberg, W.H.; Romsaas, E.P.; Tanner, M.A.; Malec, J.F. Psychosexual adaptation to breast cancer surgery. Cancer 1989, 63, 1645–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burwell, S.R.; Case, L.D.; Kaelin, C.; Avis, N.E. Sexual problems in younger women after breast cancer surgery. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 2815–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, J.M.; Lopez, M.L. Psychological problems derived from mastectomy: A qualitative study. Int. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 132461, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkes, S.; Coulson, S.; Crosland, A.; Rubin, G.; Stewart, J. Experience of fertility preservation among younger people diagnosed with cancer. Hum. Fertil. 2010, 13, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M.; O’Leary, E.; Waller, J.; Gallagher, P.; D’Arcy, T.; Flannelly, G.; Martin, C.M.; McRae, J.; Prendiville, W.; Ruttle, C.; et al. Trends in, and predictors of, anxiety and specific worries following colposcopy: A 12-month longitudinal study. Psycho-Oncology 2016, 25, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shear, M.K. Getting straight about grief. Depress. Anxiety 2012, 29, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelen, P.A.; Smid, G.E. Disturbed grief: Prolonged grief disorder and persistent complex bereavement disorder. BMJ 2017, 357, j2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milic, J.; Saavedra Perez, H.; Zuurbier, L.A.; Boelen, P.A.; Rietjens, J.A.; Hofman, A.; Tiemeier, H. The Longitudinal and Cross-Sectional Associations of Grief and Complicated Grief With Sleep Quality in Older Adults. Behav. Sleep Med. 2017, 17, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maercker, A.; Brewin, C.R.; Bryant, R.A.; Cloitre, M.; van Ommeren, M.; Jones, L.M.; Humayan, A.; Kagee, A.; Llosa, A.E.; Rousseau, C.; et al. Diagnosis and classification of disorders specifically associated with stress: Proposals for ICD-11. World Psychiatry 2013, 12, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigerson, H.G.; Horowitz, M.J.; Jacobs, S.C.; Parkes, C.M.; Aslan, M.; Goodkin, K.; Raphael, B.; Marwit, S.J.; Wortman, C.; Neimeyer, R.A.; et al. Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milic, J.; Muka, T.; Ikram, M.A.; Franco, O.H.; Tiemeier, H. Determinants and Predictors of Grief Severity and Persistence: The Rotterdam Study. J. Aging Health 2017, 29, 1288–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulton, R.; Gottesman, D.J. Anticipatory grief: A psychosocial concept reconsidered. Br. J. Psychiatry 1980, 137, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kübler-Ross, E. On Death and Dying; MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, G.; Madden, C.; Minichiello, V. The social construction of anticipatory grief. Soc. Sci. Med. 1996, 43, 1349–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.O.; Lo, R.S.; Chan, F.M.; Kwan, B.H.; Woo, J. An exploration of anticipatory grief in advanced cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 2010, 19, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, H.; Diefenbach, M.; Leventhal, E.A. Illness cognition: Using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1992, 16, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijmans, M. The role of patients’ illness representations in coping and functioning with Addison’s disease. Br. J. Health Psychol. 1999, 4 Pt 2, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökler-Danışman, I.; Yalçınay-İnan, M.; Yiğit, İ. Experience of grief by patients with cancer in relation to perceptions of illness: The mediating roles of identity centrality, stigma-induced discrimination, and hopefulness. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2017, 35, 776–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husson, O.; Thong, M.S.; Mols, F.; Oerlemans, S.; Kaptein, A.A.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V. Illness perceptions in cancer survivors: What is the role of information provision? Psycho-Oncology 2013, 22, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnasamy, M. Social support and the patient with cancer: A consideration of the literature. J. Adv. Nurs. 1996, 23, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, H.; Honda, A. Using Narrative Approach for Anticipatory Grief Among Family Caregivers at Home. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2016, 3, 2333393616682549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overton, B.L.; Cottone, R.R. Anticipatory Grief: A Family Systems Approach. Fam. J. 2016, 24, 430–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang-Rollin, I.; Berberich, G. Psycho-oncology. Dialog. Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 20, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bultz, B.D.; Travado, L.; Jacobsen, P.B.; Turner, J.; Borras, J.M.; Ullrich, A.W. 2014 President’s plenary international psycho-oncology society: Moving toward cancer care for the whole patient. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 1587–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.J.; Pillai, G.G.; Andrade, C.J.; Ligibel, J.A.; Basu, P.; Cohen, L.; Khan, I.A.; Mustian, K.M.; Puthiyedath, R.; Dhiman, K.S.; et al. Integrative oncology: Addressing the global challenges of cancer prevention and treatment. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, L.E. Psychosocial and integrative oncology: Interventions across the disease trajectory. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2023, 74, 457–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.; Mishra, A.K.; Gajera, G. Anxiety and Depression Among Breast Cancer Survivors: A Trauma Beyond Cancer. In Handbook of the Behavior and Psychology of Disease; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ajluni, V. Integrating psychiatry and family medicine in the management of somatic symptom disorders: Diagnosis, collaboration, and communication strategies. J. Gen. Fam. Med. 2025, 26, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.M.; Wahba, N.M.I.; Zaghamir, D.E.F.; Mersal, N.A.; Mersal, F.A.; Ali, R.A.E.S.; Eltaib, F.A.; Mohamed, H.A.H. Impact of a comprehensive rehabilitation palliative care program on the quality of life of patients with terminal cancer and their informal caregivers: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebri, V.; Pravettoni, G. Tailored psychological interventions to manage body image: An opinion study on breast cancer survivors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.C.; Jiang, H.J.; Lee, L.H.; Yang, C.I.; Sun, X.Y. Oncology nurses’ experiences of providing emotional support for cancer patients: A qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becqué, Y.N.; van der Wel, M.; Aktan-Arslan, M.; Driel, A.G.V.; Rietjens, J.A.; van der Heide, A.; Witkamp, E. Supportive interventions for family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology 2023, 32, 663–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chia, K.H. The Psychosocial Developmental Phases of Death (Mortality) Awareness: What Educational Therapists should know when working with Terminally Ill Clients. Asian J. Interdiscip. Res. 2024, 7, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdoun, S.; Monteleone, R.; Bookman, T.; Michael, K. AI-based and digital mental health apps: Balancing need and risk. IEEE Technol. Soc. Mag. 2023, 42, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthal, W.G.; Roberts, K.E.; Donovan, L.A.; Breen, L.J.; Aoun, S.M.; Connor, S.R.; Rosa, W.E. Investing in bereavement care as a public health priority. Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, e270–e274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Milic, J.; Vucurovic, M.; Grego, E.; Jovic, D.; Sapic, R.; Jovic, S.; Jovanovic, V. From Fear to Hope: Understanding Preparatory and Anticipatory Grief in Women with Cancer—A Public Health Approach to Integrating Screening, Compassionate Communication, and Psychological Support Strategies. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3621. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113621

Milic J, Vucurovic M, Grego E, Jovic D, Sapic R, Jovic S, Jovanovic V. From Fear to Hope: Understanding Preparatory and Anticipatory Grief in Women with Cancer—A Public Health Approach to Integrating Screening, Compassionate Communication, and Psychological Support Strategies. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(11):3621. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113621

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilic, Jelena, Milica Vucurovic, Edita Grego, Dragana Jovic, Rosa Sapic, Sladjana Jovic, and Verica Jovanovic. 2025. "From Fear to Hope: Understanding Preparatory and Anticipatory Grief in Women with Cancer—A Public Health Approach to Integrating Screening, Compassionate Communication, and Psychological Support Strategies" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 11: 3621. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113621

APA StyleMilic, J., Vucurovic, M., Grego, E., Jovic, D., Sapic, R., Jovic, S., & Jovanovic, V. (2025). From Fear to Hope: Understanding Preparatory and Anticipatory Grief in Women with Cancer—A Public Health Approach to Integrating Screening, Compassionate Communication, and Psychological Support Strategies. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(11), 3621. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14113621