Public Perception of Clinical Trials and Its Predictors Among Polish Adults

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedure

2.2. Dependent Variables

2.3. Independent Variables

- Gender: men and women;

- Age groups: 18–35 years old; 36–50 years old, 51–65 years old, 66 years old or older;

- Place of residence: urban and rural;

- Education level: below secondary, secondary, above secondary;

- Being in a stable relationship in categories: yes, no;

- Current employment status: yes, no;

- Financial status coded into four categories: low, average, rather high, and definitely high.

Health-Related Factors

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Interest in Participating in Clinical Trials in the Future

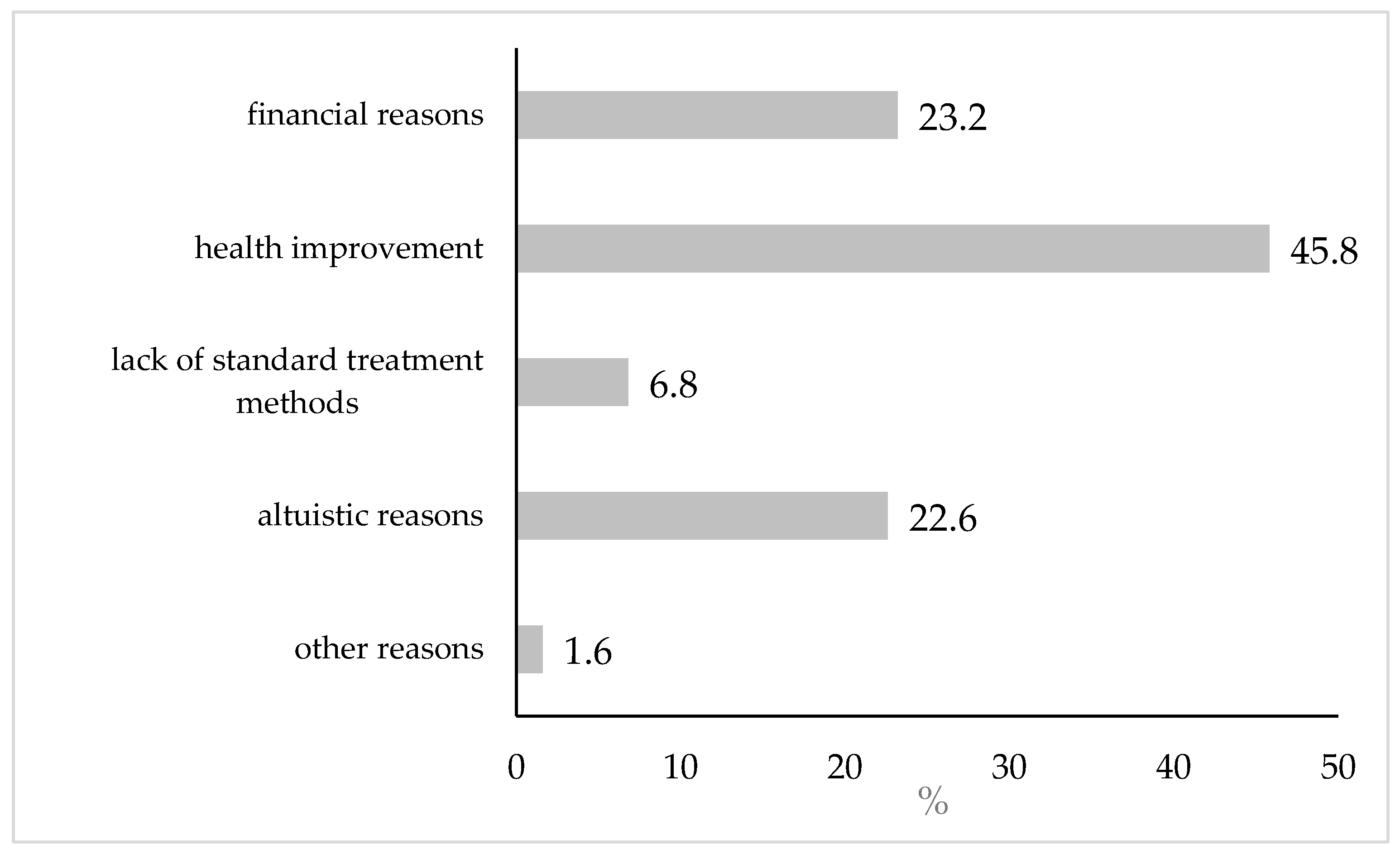

3.2.1. Prevalence and Primary Reasons for Interest

3.2.2. Univariate Analysis Determinants

3.2.3. Multivariate Logistic Model

3.3. Perceived Health Impact

3.3.1. Structure and Distribution of the CT-PHI Index

3.3.2. CT-PHI Index Level in Univariate Analysis

3.3.3. Multivariate Linear Model

3.3.4. Stratification by Primary Reason for Interest in Clinical Trials

4. Discussion

4.1. Approach to Clinical Trials and Demographic and Social Characteristics of Respondents

4.2. Approach to Clinical Trials and the Severity of Health Problems

4.3. Approach to Clinical Trials and the Use of Medical Care

4.4. Summary of Multivariate Analysis

4.5. Practical Implications for Recruitment Campaigns in Poland

4.6. Strenghts and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of items | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| Covariance between residuals | - | - | e1 & e3 |

| CMIN/DF | 19.44 | 26.50 | 4.10 |

| RMSEA—Root Mean Square Error of Approximation | 0.126 | 0.149 | 0.052 |

| 95% CI (RMSEA) | 0.110–0.143 | 0.127–0.171 | 0.027–0.079 |

| NFI—Normed Fit Index | 0.944 | 0.954 | 0.994 |

| RFI—Relative Fit Index | 0.906 | 0.907 | 0.986 |

| TLI—Tucker Lewis index | 0.910 | 0.910 | 0.989 |

| CFI—Comparative Fit Index | 0.946 | 0.955 | 0.996 |

| Modification indices | |||

| Number | 12 | 5 | 3 |

| Range | 4.19–97.55 | 6.20–108.17 | 4.42–6.15 |

| Standardized regression weights | |||

| Item1 <- CT-PHI | 0.658 | 0.649 | 0.610 |

| Item2 <- CT-PHI | 0.427 | - | - |

| Item3 <- CT-PHI | 0.713 | 0.707 | 0.674 |

| Item4 <- CT-PHI | 0.858 | 0.862 | 0.868 |

| Item5 <- CT-PHI | 0.750 | 0.747 | 0.755 |

| Item6 <- CT-PHI | 0.818 | 0.824 | 0.834 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

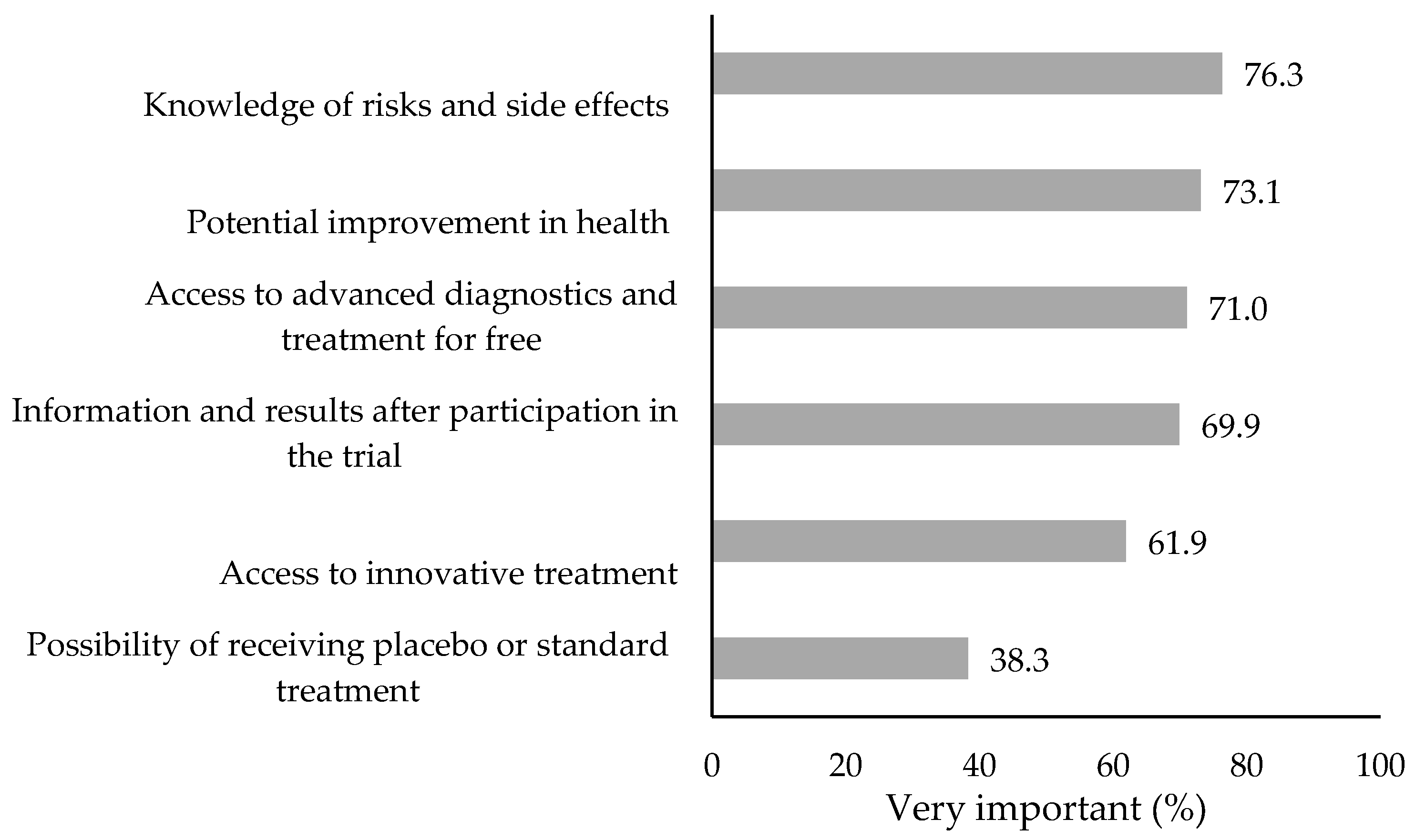

| Responses: very important; rather important; neither important nor unimportant; rather unimportant; not important at all (reverse coding for CT-PHI index development). |

References

- World Health Organization International Standards for Clinical Trial Registries: The Registration of All Interventional Trials Is a Scientific, Ethical and Moral Responsibility; Version 3.0; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-92-4-151474-3.

- Available online: https://pacjentwbadaniach.abm.gov.pl/pwb/o-badaniach-klinicznych/czym-sa-badania-kliniczne/definicje-badania-klini/110,definicje-badania-klinicznego.html (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Sapsford, R.; Abbott, P. Trust, Confidence and Social Environment in Post-Communist Societies. Communist Post-Communist Stud. 2006, 39, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Poland: Country Health Profile 2021; State of Health in the EU; OECD: Paris, France, 2021; ISBN 978-92-64-46566-4. [Google Scholar]

- Misik, V.; Jarosz, B. Komercyjne Badania Kliniczne w Polsce: Możliwości Zwiększenia Liczby i Zakresu Badań Klinicznych w Polsce; INFARMA: Warszawa, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cięszczyk, N.; Czech, M.; Pronicki, Ł.; Gujski, M. Knowledge and Beliefs About Clinical Trials Among Adults in Poland: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clin. Pract. 2024, 14, 1285–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilicel, D.; De Crescenzo, F.; Pontrelli, G.; Armando, M. Participant Recruitment Issues in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinical Trials with a Focus on Prevention Programs: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booker, C.L.; Harding, S.; Benzeval, M. A Systematic Review of the Effect of Retention Methods in Population-Based Cohort Studies. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasi, J.K.; Capili, B.; Norton, M.; McMahon, D.J.; Marder, K. Recruitment and Retention of Clinical Trial Participants: Understanding Motivations of Patients with Chronic Pain and Other Populations. Front. Pain Res. 2024, 4, 1330937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, A.; Rose, F.; Jones, K.; Scantlebury, A.; Adamson, J.; Knapp, P. Why Do People Take Part in Vaccine Trials? A Mixed Methods Narrative Synthesis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2023, 114, 107861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobra, R.; Wilson, G.; Matthews, J.; Boeri, M.; Elborn, S.; Kee, F.; Davies, J.C.; Madge, S. A Systematic Review to Identify and Collate Factors Influencing Patient Journeys Through Clinical Trials. JRSM Open 2023, 14, 205427042311666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newington, L.; Alexander, C.M.; Kirby, P.; Saggu, R.K.; Wells, M. Reflections on Contributing to Health Research: A Qualitative Interview Study with Research Participants and Patient Advisors. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0279354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.A.; Song, W.B.; Jiao, M.; O’Brien, E.; Ubel, P.; Wang, G.; Scales, C.D. Strategies for Research Participant Engagement: A Synthetic Review and Conceptual Framework. Clin. Trials 2021, 18, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilton, J.A.; Rasmus, M.L.; Lytton, J.; Kaplan, C.D.; Jones, L.A.; Hurd, T.C. Ambivalence: A Key to Clinical Trial Participation? Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, F.; Matzneller, P.; Weber, M.; Yeghiazaryan, L.; Fuereder, T.; Weber, T.; Zeitlinger, M. Perception of Clinical Research Among Patients and Healthy Volunteers of Clinical Trials. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 78, 1647–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mello, M.M.; Lieou, V.; Goodman, S.N. Clinical Trial Participants’ Views of the Risks and Benefits of Data Sharing. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2202–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, W.A.; Melvin, K.C.; Doorenbos, A.Z. US Military Service Members’ Reasons for Deciding to Participate in Health Research. Res. Nurs. Health 2017, 40, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowton, K. Trials and Tribulations: Understanding Motivations for Clinical Research Participation Amongst Adults with Cystic Fibrosis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 1854–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCann, S.K.; Campbell, M.K.; Entwistle, V.A. Reasons for Participating in Randomised Controlled Trials: Conditional Altruism and Considerations for Self. Trials 2010, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainesi, S.M.; Goldbaum, M. Reasons behind the Participation in Biomedical Research: A Brief Review. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2014, 17, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.C.; McNicol, E.; Kleykamp, B.A.; Sandoval, K.; Haroutounian, S.; Holzer, K.J.; Kerns, R.D.; Veasley, C.; Turk, D.C.; Dworkin, R.H. Perspectives on Participation in Clinical Trials Among Individuals with Pain, Depression, and/or Anxiety: An ACTTION Scoping Review. J. Pain 2023, 24, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflugeisen, B.M.; Rebar, S.; Reedy, A.; Pierce, R.; Amoroso, P.J. Assessment of Clinical Trial Participant Patient Satisfaction: A Call to Action. Trials 2016, 17, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappo, S.A.; Iafrate, G.B.; Sanchez, Z.M. Motives for Participating in a Clinical Research Trial: A Pilot Study in Brazil. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paço, A.; Ferreira, M.; Leal, J. Motivations for Participating in Clinical Trials and Health-Related Product Testing. J. Med. Mark. 2015, 15, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stunkel, L.; Grady, C. More than the Money: A Review of the Literature Examining Healthy Volunteer Motivations. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2011, 32, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iltis, A.S. Payments to Normal Healthy Volunteers in Phase 1 Trials: Avoiding Undue Influence While Distributing Fairly the Burdens of Research Participation. J. Med. Philos. 2009, 34, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler, O. The Professional Guinea Pig: Big Pharma and the Risky World of Human Subjects. Cad. Saúde Pública 2011, 27, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manton, K.J.; Gauld, C.S.; White, K.M.; Griffin, P.M.; Elliott, S.L. Qualitative Study Investigating the Underlying Motivations of Healthy Participants in Phase I Clinical Trials. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, F.; Charasz, N. Attitudes of Older Adults to Their Participation in Clinical Trials: A Pilot Study. Drugs Aging 2014, 31, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, J.R.; De Wit, M.; Frank, L.; Haywood, K.L.; Salek, S.; Brace-McDonnell, S.; Lyddiatt, A.; Barbic, S.P.; Alonso, J.; Guillemin, F.; et al. Emerging Guidelines for Patient Engagement in Research. Value Health 2017, 20, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.; Borfitz, D.; Getz, K. Global Public Attitudes About Clinical Research and Patient Experiences with Clinical Trials. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e182969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.pratia.pl/blog/czy-polacy-boja-sie-badan-klinicznych/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Izdebski, Z.; Mazur, J.; Furman, K.; Kozakiewicz, A.; Białorudzki, M. Humanization of the Treatment Process and Clinical Communication Between Patients and Medical Staff During the COVID-19 Pandemic; University of Warsaw Press: Warsaw, Poland, 2023; ISBN 978-83-235-6018-0. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DasMahapatra, P.; Raja, P.; Gilbert, J.; Wicks, P. Clinical Trials from the Patient Perspective: Survey in an Online Patient Community. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, A.; Elmer, M.; Ludlam, S.; Shay, K.; Bentley, S.; Trennery, C.; Grimes, R.; Gater, A. Evaluation of the Content Validity and Cross-Cultural Validity of the Study Participant Feedback Questionnaire (SPFQ). Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2020, 54, 1522–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golicki, D.; Jakubczyk, M.; Graczyk, K.; Niewada, M. Valuation of EQ-5D-5L Health States in Poland: The First EQ-VT-Based Study in Central and Eastern Europe. PharmacoEconomics 2019, 37, 1165–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herdman, M.; Gudex, C.; Lloyd, A.; Janssen, M.f.; Kind, P.; Parkin, D.; Bonsel, G.; Badia, X. Development and Preliminary Testing of the New Five-Level Version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual. Life Res. 2011, 20, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny Statistics Poland Powierzchnia i Ludność w Przekroju Terytorialnym w 2022 r. Area and Population in the Territorial Profile in 2022; Główny Urząd Statystyczny: Warsaw, Poland, 2022.

- Gudaszewski, G.; Kaczorowski, P.; Chmielewska, A.; Kuchta, A.; Szymczuk-Kupryś, M.; Stelmach, K.; Cierniak-Piotrowska, M.; Potocka, M.; Wysocka, A.; Szałtys, D. (Eds.) National Population and Housing Census 2021: Population: Size and Demographic-Social Structure in the Light of the 2021 Census Results; Censuses/Statistics Poland; Statistics Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2023; ISBN 978-83-67087-55-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, J.A.; McManus, L.; Wood, M.M.; Cottingham, M.D.; Kalbaugh, J.M.; Monahan, T.; Walker, R.L. Healthy Volunteers’ Perceptions of the Benefits of Their Participation in Phase I Clinical Trials. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2018, 13, 494–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzalmate-Hajjaj, A.; Massó Guijarro, P.; Khan, K.S.; Bueno-Cavanillas, A.; Cano-Ibáñez, N. Benefits of Participation in Clinical Trials: An Umbrella Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.; Azevedo, B.; Nunes, T.; Vaz-da-Silva, M.; Soares-da-Silva, P. Why Healthy Subjects Volunteer for Phase I Studies and How They Perceive Their Participation? Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007, 63, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Florez, M.; Botto, E.; Belgrave, X.; Grace, C.; Getz, K. The Influence of Socioeconomic Status on Individual Attitudes and Experience with Clinical Trials. Commun. Med. 2024, 4, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhakar, S.; Aebi, M.E.; Burant, C.J.; Wilson, B.; Wenk, J.; Briggs, F.B.S.; Pyatka, N.; Blixen, C.; Sajatovic, M. Health Literacy and Education Level Correlates of Participation and Outcome in a Remotely Delivered Epilepsy Self-Management Program. Epilepsy Behav. 2020, 107, 107026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, S.R.; Li, J.; Quay, B. Employment Status, Unemployment Duration, and Health-Related Metrics Among US Adults of Prime Working Age: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2018–2019. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2022, 65, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, J.P.; Tomy, S.K.; Jose, A.; Kashyap, A.; Kureethara, J.V.; Kallarakal, T.K. Knowledge and Perceptions About Clinical Research and Its Ethical Conduct Among College Students from Non-Science Background: A Representative Nation-Wide Survey from India. Bmjph 2024, 2, e000748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharucha, A.E.; Wi, C.I.; Srinivasan, S.G.; Choi, H.; Wheeler, P.H.; Stavlund, J.R.; Keller, D.A.; Bailey, K.R.; Juhn, Y.J. Participation of Rural Patients in Clinical Trials at a Multisite Academic Medical Center. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 5, e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazeau, H.; Lewis, N.A. Within-Couple Health Behavior Trajectories: The Role of Spousal Support and Strain. Health Psychol. 2021, 40, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robiner, W.N.; Yozwiak, J.A.; Bearman, D.L.; Strand, T.D.; Strasburg, K.R. Barriers to Clinical Research Participation in a Diabetes Randomized Clinical Trial. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 1069–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobato, L.; Bethony, J.M.; Pereira, F.B.; Grahek, S.L.; Diemert, D.; Gazzinelli, M.F. Impact of Gender on the Decision to Participate in a Clinical Trial: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickard, S. Age Studies: A Sociological Examination of How We Age and Are Aged Through the Life Course; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4462-8737-8. [Google Scholar]

- Porreca, F.; Navratilova, E. Reward, Motivation, and Emotion of Pain and Its Relief. Pain 2017, 158, S43–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, R.J. Continued High Prevalence and Adverse Clinical Impact of Human Immunodeficiency Virus–Associated Sensory Neuropathy in the Era of Combination Antiretroviral Therapy: The CHARTER Study. Arch. Neurol. 2010, 67, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hans, G.H.; Almeshal, D.; Vanlommel, L.; Roelant, E.; Verhaegen, I.; Smits, E.; Van Boxem, K.; Fontaine, R. Considerations on the Obstacles That Lead to Slow Recruitment in a Pain Management Clinical Trial: Experiences from the Belgian PELICAN (PrEgabalin Lidocaine Capsaicin Neuropathic Pain) Pragmatic Study. Pain Res. Manag. 2023, 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agoritsas, T.; Deom, M.; Perneger, T.V. Study Design Attributes Influenced Patients’ Willingness to Participate in Clinical Research: A Randomized Vignette-Based Study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trauth, J.M.; Musa, D.; Siminoff, L.; Jewell, I.K.; Ricci, E. Public Attitudes Regarding Willingness to Participate in Medical Research Studies. J. Health Soc. Policy 2000, 12, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilles, T.; Mortelmans, L.; Loots, E.; Sabbe, K.; Feyen, H.; Wauters, M.; Haegdorens, F.; De Baetselier, E. People-Centered Care and Patients’ Beliefs About Medicines and Adherence: A Cross-Sectional Study. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwingmann, J.; Baile, W.F.; Schmier, J.W.; Bernhard, J.; Keller, M. Effects of Patient-Centered Communication on Anxiety, Negative Affect, and Trust in the Physician in Delivering a Cancer Diagnosis: A Randomized, Experimental Study. Cancer 2017, 123, 3167–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niranjan, S.J.; Martin, M.Y.; Fouad, M.N.; Vickers, S.M.; Wenzel, J.A.; Cook, E.D.; Konety, B.R.; Durant, R.W. Bias and Stereotyping Among Research and Clinical Professionals: Perspectives on Minority Recruitment for Oncology Clinical Trials. Cancer 2020, 126, 1958–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodou, D.; De Winter, J.C.F. Social Desirability Is the Same in Offline, Online, and Paper Surveys: A Meta-Analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 36, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterrett, D.; Malato, D.; Benz, J.; Tompson, T.; English, N. Assessing Changes in Coverage Bias of Web Surveys in the United States. Public Opin. Q. 2017, 81, 338–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, J.; Dawson, L.; Rid, A. The Social Value Misconception in Clinical Research. Am. J. Bioeth. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamp, E.; Schofield, H.; Roberts, V.L.; Burton, W.; Collinson, M.; Stevens, J.; Farrin, A.; Rutter, H.; Bryant, M. Contamination Within Trials of Community-Based Public Health Interventions: Lessons from the HENRY Feasibility Study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2021, 7, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson Charles, R.M.; Sosa, E.; Patel, M.; Erhunmwunsee, L. Health Disparities in Recruitment and Enrollment in Research. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 2022, 32, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N (%) | Interest in Participation (%) | p * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Men | 1025 (50.0) | 57.8 | 42.2 | 0.197 |

| Women | 1025 (50.0) | 54.9 | 45.1 | |

| Age in years | ||||

| 18–35 | 510 (24.9) | 53.5 | 46.5 | |

| 36–50 | 552 (26.9) | 60.3 | 39.7 | 0.096 |

| 52–65 | 588 (28.7) | 56.8 | 43.2 | |

| 66+ | 400 (19.5) | 53.8 | 46.3 | |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 1316 (64.2) | 56.5 | 43.5 | 0.886 |

| Rural | 734 (35.8) | 56.1 | 43.9 | |

| Education | ||||

| Below secondary | 556 (27.1) | 55.8 | 44.2 | |

| Secondary | 728 (35.5) | 56.2 | 43.8 | 0.910 |

| Above secondary | 766 (37.4) | 56.9 | 43.1 | |

| Being in a stable relationship | ||||

| Yes | 1466 (72.6) | 58.0 | 42.0 | 0.023 |

| No | 553 (27.4) | 52.4 | 47.6 | |

| Occupational work | ||||

| Yes | 1027 (50.5) | 59.4 | 40.6 | 0.005 |

| No | 1005 (49.5) | 53.2 | 46.8 | |

| Financial status | ||||

| Low | 298 (14.9) | 62.8 | 37.2 | |

| Average | 1087 (54.3) | 57.8 | 42.2 | 0.016 |

| Rather high | 353 (17.6) | 51.6 | 48.4 | |

| Definitely high | 265 (13.2) | 52.8 | 47.2 | |

| Self-perceived health | ||||

| Poor | 442 (21.6) | 62.9 | 37.1 | |

| Average | 638 (31.2) | 53.9 | 46.1 | 0.008 |

| Good | 964 (47.2) | 55.2 | 44.8 | |

| Knowing the rights of patients | ||||

| No knowledge | 135 (6.6) | 54.8 | 45.2 | |

| Limited awareness | 1445 (70.5) | 55.8 | 44.2 | 0.545 |

| Comprehensive knowledge | 470 (22.9) | 58.5 | 41.5 | |

| Healthcare | ||||

| Public only | 900 (43.9) | 58.0 | 42.0 | |

| Private only | 61 (3.0) | 45.9 | 54.1 | 0.137 |

| Both public and private | 1089 (53.1) | 55.6 | 44.4 | |

| Adherence to treatment | ||||

| Rarely or not at all | 148 (7.2) | 59.5 | 40.5 | |

| Almost always | 1064 (52.1) | 56.1 | 43.9 | 0.740 |

| Always | 831 (40.7) | 56.3 | 43.7 | |

| Problems with: | N (%) * | Interest in Participation (%) (N = 2050) | CT-PHI Index (N = 1155) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | p ** | M ± SD | p *** | ||

| Mobility | ||||||

| No problems | 1380 (67.3) | 54.7 | 45.3 | 18.22 ± 2.47 | ||

| Slight problems | 379 (18.5) | 59.4 | 40.6 | 0.124 | 18.07 ± 2.74 | 0.885 |

| Moderate problems | 195 (9.5) | 57.9 | 42.1 | 17.99 ± 2.87 | ||

| Severe problems/incapacity | 96 (4.7) | 64.6 | 35.4 | 18.16 ± 2.46 | ||

| Self-care | ||||||

| No problems | 1810 (88.3) | 55.5 | 44.5 | 18.26 ± 2.48 | ||

| Slight problems | 144 (7.0) | 61.1 | 38.9 | 0.190 | 17.99 ± 2.74 | <0.001 |

| Moderate problems | 71 (3.5) | 66.2 | 33.8 | 16.53 ± 3.30 | ||

| Severe problems/incapacity | 25 (1.2) | 60.0 | 40.0 | 17.80 ± 2.88 | ||

| Usual activities | ||||||

| No problems | 1569 (76.5) | 54.9 | 45.1 | 18.23 ± 2.49 | ||

| Slight problems | 294 (14.4) | 61.2 | 38.8 | 0.136 | 18.27 ± 2.41 | 0.272 |

| Moderate problems | 141 (6.9) | 59.6 | 40.4 | 17.40 ± 3.29 | ||

| Severe problems/incapacity | 46 (2.2) | 63.0 | 37.0 | 17.76 ± 2.92 | ||

| Pain/discomfort | ||||||

| No | 573 (28.0) | 54.5 | 45.5 | 17.76 ± 2.87 | ||

| Slight | 774 (37.7) | 53.6 | 46.4 | 0.011 | 18.23 ± 2.43 | 0.014 |

| Moderate | 523 (25.5) | 59.3 | 40.7 | 18.40 ± 2.30 | ||

| Severe/extreme | 180 (8.8) | 65.6 | 34.3 | 18.37 ± 2.69 | ||

| Anxiety/depression | ||||||

| No | 694 (33.9) | 53.7 | 46.3 | 18.17 ± 2.68 | ||

| Slight | 710 (34.6) | 55.9 | 44.1 | 0.043 | 18.22 ± 2.40 | 0.445 |

| Moderate | 385 (18.8) | 56.6 | 43.4 | 18.26 ± 2.45 | ||

| Severe/extreme | 261 (12.7) | 64.0 | 36.0 | 17.88 ± 2.80 | ||

| Independent Variables | B | SE(B) | p | OR | 95% CI(OR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupational work | |||||

| Yes | 0.296 | 0.094 | 0.002 | 1.345 | 1.119–1.616 |

| No (ref.) | 1.000 | ||||

| Being in stable relationship | |||||

| Yes | 0.215 | 0.104 | 0.038 | 1.240 | 1.012–1.520 |

| No (ref.) | 1.000 | ||||

| Financial status | 0.028 | ||||

| Low | 0.353 | 0.178 | 0.047 | 1.423 | 1.004–2.017 |

| Average | 0.167 | 0.141 | 0.234 | 1.182 | 0.898–1.557 |

| Rather high | −0.105 | 0.165 | 0.523 | 0.900 | 0.651–1.244 |

| Definitely high (ref.) | 1.000 | ||||

| Pain/discomfort (EQ-5D-5L) | 0.015 | ||||

| No (ref.) | 1.000 | ||||

| Slight | −0.021 | 0.115 | 0.858 | 0.980 | 0.783–1.226 |

| Moderate | 0.175 | 0.128 | 0.169 | 1.192 | 0.928–1.530 |

| Severe/extreme | 0.517 | 0.189 | 0.006 | 1.677 | 1.159–2.426 |

| Variables | N (%) | M ± SD | p * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Men | 592 (51.3) | 17.85 ± 2.72 | <0.001 |

| Women | 563 (48.7) | 18.49 ± 2.35 | |

| Age in years | |||

| 18–35 | 273 (23.6) | 17.24 ± 2.91 | |

| 36–50 | 333 (28.9) | 17.92 ± 2.73 | <0.001 |

| 52–65 | 334 (28.9) | 18.70 ± 2.27 | |

| 66+ | 215 (18.6) | 18.87 ± 1.69 | |

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 743 (64.3) | 18.05 ± 2.71 | 0.115 |

| Rural | 412 (35.7) | 18.37 ± 2.27 | |

| Education | |||

| Below secondary | 310 (26.8) | 17.75 ± 2.94 | |

| Secondary | 409 (35.5) | 18.33 ± 2.45 | 0.004 |

| Above secondary | 436 (37.7) | 18.30 ± 2.35 | |

| Being in a stable relationship | |||

| Yes | 851 (74.6) | 18.18 ± 2.61 | 0.391 |

| No | 290 (25.4) | 18.09 ± 2.44 | |

| Occupational work | |||

| Yes | 610 (53.3) | 18.00 ± 2.74 | 0.095 |

| No | 535 (46.7) | 18.37 ± 2.30 | |

| Financial status | |||

| Low | 187 (16.4) | 18.28 ± 2.50 | |

| Average | 628 (55.3) | 18.27 ± 2.49 | 0.252 |

| Rather high | 182 (16.0) | 17.84 ± 2.80 | |

| Definitely high | 140 (12.3) | 18.08 ± 2.44 | |

| Self-perceived health | |||

| Poor | 278 (24.1) | 18.35 ± 2.40 | |

| Average | 344 (29.8) | 17.96 ± 2.81 | 0.368 |

| Good | 532 (46.1) | 18.21 ± 2.44 | |

| Knowing the rights of patients | |||

| No knowledge | 74 (6.4) | 17.22 ± 3.32 | |

| Limited awareness | 806 (69.8) | 18.09 ± 2.63 | <0.001 |

| Comprehensive knowledge | 275 (23.8) | 18.64 ± 2.00 | |

| Healthcare | |||

| Public only | 522 (45.2) | 17.98 ± 2.68 | |

| Private only | 28 (2.4) | 16.36 ± 4.00 | <0.001 |

| Both public and private | 605 (52.4) | 18.40 ± 2.32 | |

| Adherence to treatment | |||

| Rarely or not at all | 88 (7.6) | 16.01 ± 3.67 | |

| Almost always | 597 (51.8) | 18.08 ± 2.39 | <0.001 |

| Always | 468 (40.6) | 18.71 ± 2.22 |

| Independent Variable * | B | SE(B) | p ** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 15.263 | 0.334 | <0.001 |

| Female | 0.517 | 0.139 | <0.001 |

| Age in years | |||

| 66 or more | 1.554 | 0.221 | <0.001 |

| 51–65 | 1.418 | 0.197 | <0.001 |

| 36–50 | 0.630 | 0.192 | 0.001 |

| Residence—rural | 0.326 | 0.147 | 0.026 |

| Self-perceived health | |||

| Good | −0.128 | 0.182 | 0.484 |

| Average | −0.478 | 0.193 | 0.013 |

| Healthcare | |||

| Both public and private | 0.451 | 0.139 | 0.001 |

| Only private | −0.191 | 0.474 | 0.687 |

| Adherence to treatment | |||

| Always | 2.071 | 0.277 | <0.001 |

| Almost always | 1.734 | 0.269 | <0.001 |

| Self-care problems (EQ-5D-5L) | |||

| Severe/incapacity | −0.443 | 0.611 | 0.468 |

| Moderate | −1.485 | 0.356 | <0.001 |

| Slight | −0.443 | 0.267 | 0.097 |

| Independent Variables * | Financial Reasons (N = 260) | Health Improvement (N = 511) | Altruistic Reasons (N = 254) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE(B) | p ** | B | SE(B) | p ** | B | SE(B) | p ** | |

| Constant | 16.75 | 0.99 | 0.000 | 14.46 | 0.59 | 0.000 | 16.09 | 1.39 | 0.000 |

| Gender female | −0.01 | 0.35 | 0.971 | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.034 | 0.88 | 0.32 | 0.006 |

| Age in years | |||||||||

| 66 or more | 2.02 | 0.77 | 0.009 | 1.24 | 0.34 | 0.000 | 1.17 | 0.57 | 0.040 |

| 51–65 | 1.21 | 0.48 | 0.011 | 1.09 | 0.30 | 0.000 | 0.99 | 0.46 | 0.032 |

| 36–50 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.314 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.265 | 0.34 | 0.44 | 0.440 |

| Residence—rural | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.176 | 0.41 | 0.19 | 0.033 | 0.18 | 0.33 | 0.595 |

| Being single | −1.11 | 0.41 | 0.007 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.486 | −0.64 | 0.36 | 0.073 |

| Financial status | |||||||||

| Definitely high | 0.15 | 0.64 | 0.813 | −0.10 | 0.36 | 0.780 | −0.65 | 0.67 | 0.329 |

| Rather high | −0.65 | 0.57 | 0.259 | −0.73 | 0.34 | 0.031 | −0.63 | 0.62 | 0.311 |

| Average | −0.32 | 0.41 | 0.442 | −0.56 | 0.26 | 0.033 | 0.04 | 0.55 | 0.940 |

| Heath care | |||||||||

| Both public and private | 0.08 | 0.34 | 0.814 | 0.64 | 0.18 | 0.001 | −0.18 | 0.32 | 0.587 |

| Only private | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.340 | −0.33 | 0.77 | 0.664 | −0.66 | 0.99 | 0.504 |

| Adherence to treatment | |||||||||

| Always | 1.66 | 0.57 | 0.003 | 2.50 | 0.39 | 0.000 | 1.36 | 0.72 | 0.060 |

| Almost always | 1.66 | 0.54 | 0.002 | 2.21 | 0.38 | 0.000 | 0.75 | 0.73 | 0.302 |

| Self-care (EQ-5D-5L) | |||||||||

| Severe problems/incapacity | 0.57 | 1.59 | 0.720 | −3.12 | 1.09 | 0.004 | −4.55 | 3.57 | 0.202 |

| Moderate problems | −1.33 | 1.06 | 0.210 | −2.54 | 0.59 | 0.000 | 0.70 | 1.43 | 0.627 |

| Slight problems | −1.96 | 0.93 | 0.035 | −0.49 | 0.36 | 0.176 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.313 |

| Pain/discomfort (EQ-5D-5L) | |||||||||

| Severe/extreme | 2.57 | 0.97 | 0.008 | 0.91 | 0.40 | 0.023 | −0.72 | 0.82 | 0.380 |

| Moderate | 0.25 | 0.51 | 0.616 | 1.36 | 0.31 | 0.000 | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.929 |

| Slight | 0.09 | 0.41 | 0.827 | 1.02 | 0.27 | 0.000 | −0.22 | 0.38 | 0.565 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kozakiewicz, A.; Mazur, J.; Szkultecka-Dębek, M.; Białorudzki, M.; Izdebski, Z. Public Perception of Clinical Trials and Its Predictors Among Polish Adults. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3279. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103279

Kozakiewicz A, Mazur J, Szkultecka-Dębek M, Białorudzki M, Izdebski Z. Public Perception of Clinical Trials and Its Predictors Among Polish Adults. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(10):3279. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103279

Chicago/Turabian StyleKozakiewicz, Alicja, Joanna Mazur, Monika Szkultecka-Dębek, Maciej Białorudzki, and Zbigniew Izdebski. 2025. "Public Perception of Clinical Trials and Its Predictors Among Polish Adults" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 10: 3279. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103279

APA StyleKozakiewicz, A., Mazur, J., Szkultecka-Dębek, M., Białorudzki, M., & Izdebski, Z. (2025). Public Perception of Clinical Trials and Its Predictors Among Polish Adults. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(10), 3279. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14103279