Snus Use in Adolescents: A Threat to Oral Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. The Inclusion Criteria for the Study

2.3. The Exclusion Criteria for the Study

2.4. Setting and Study Design

2.5. Reliability of Examiners

2.6. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

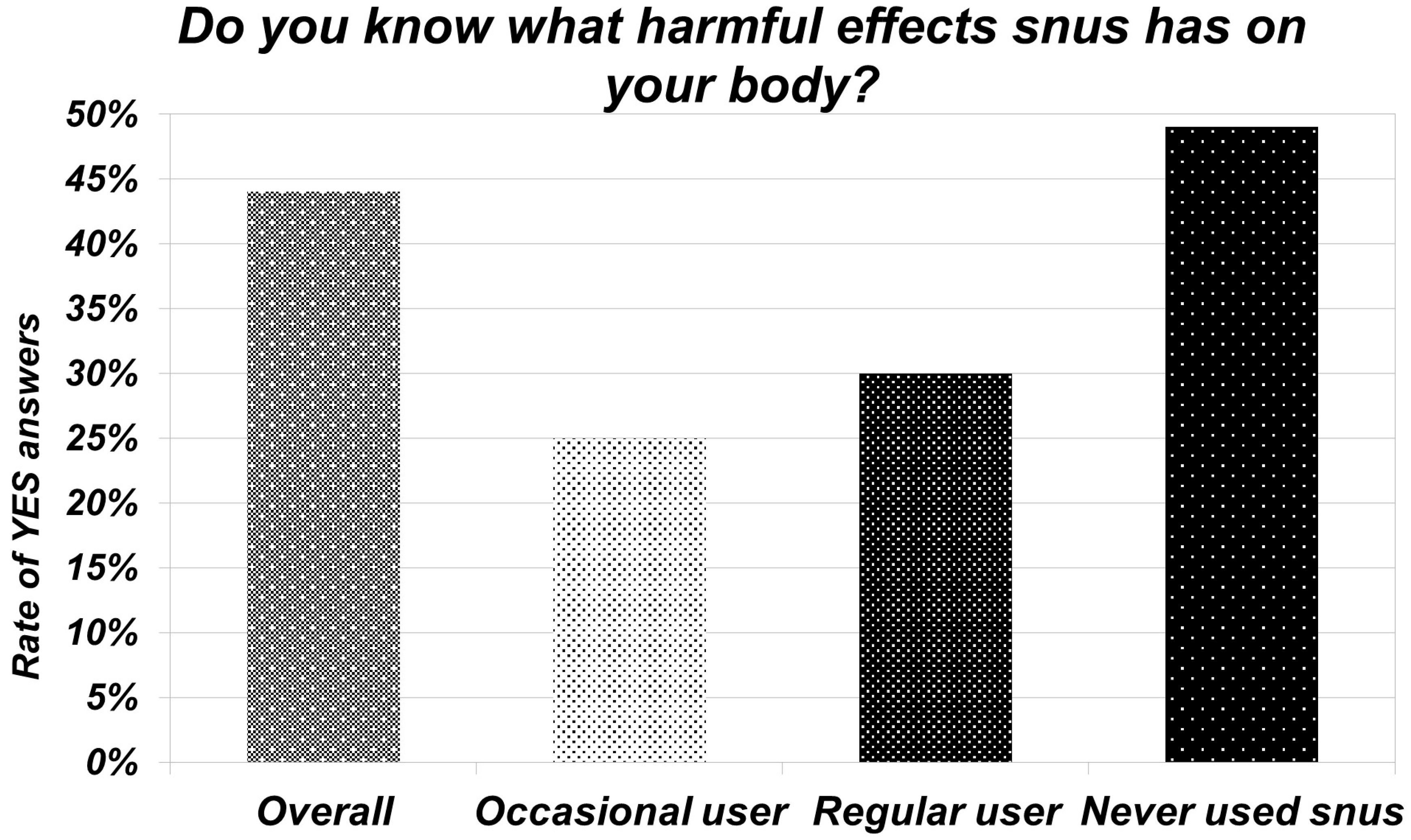

3.2. Knowledge about Snus

3.3. Snus Habits

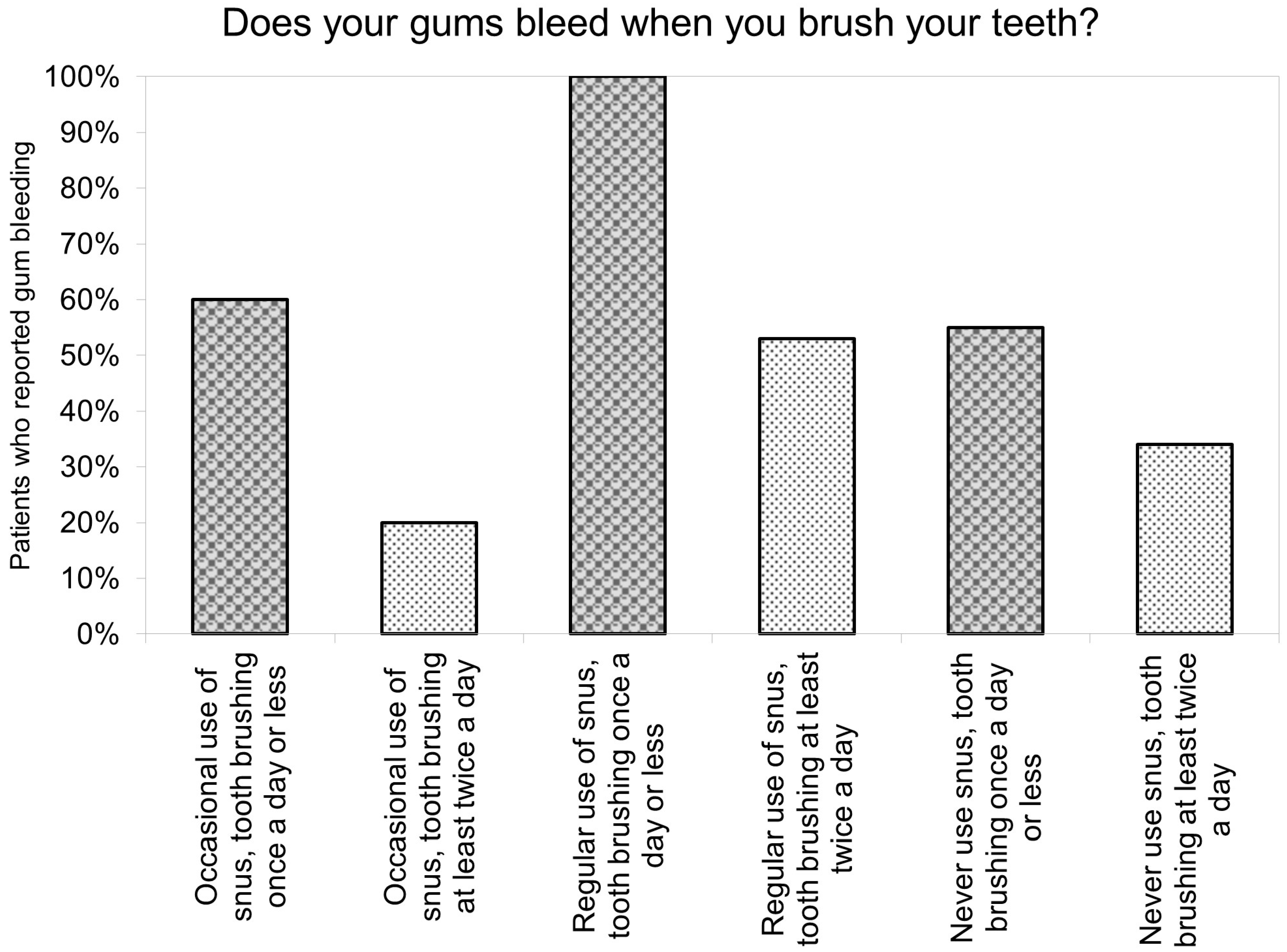

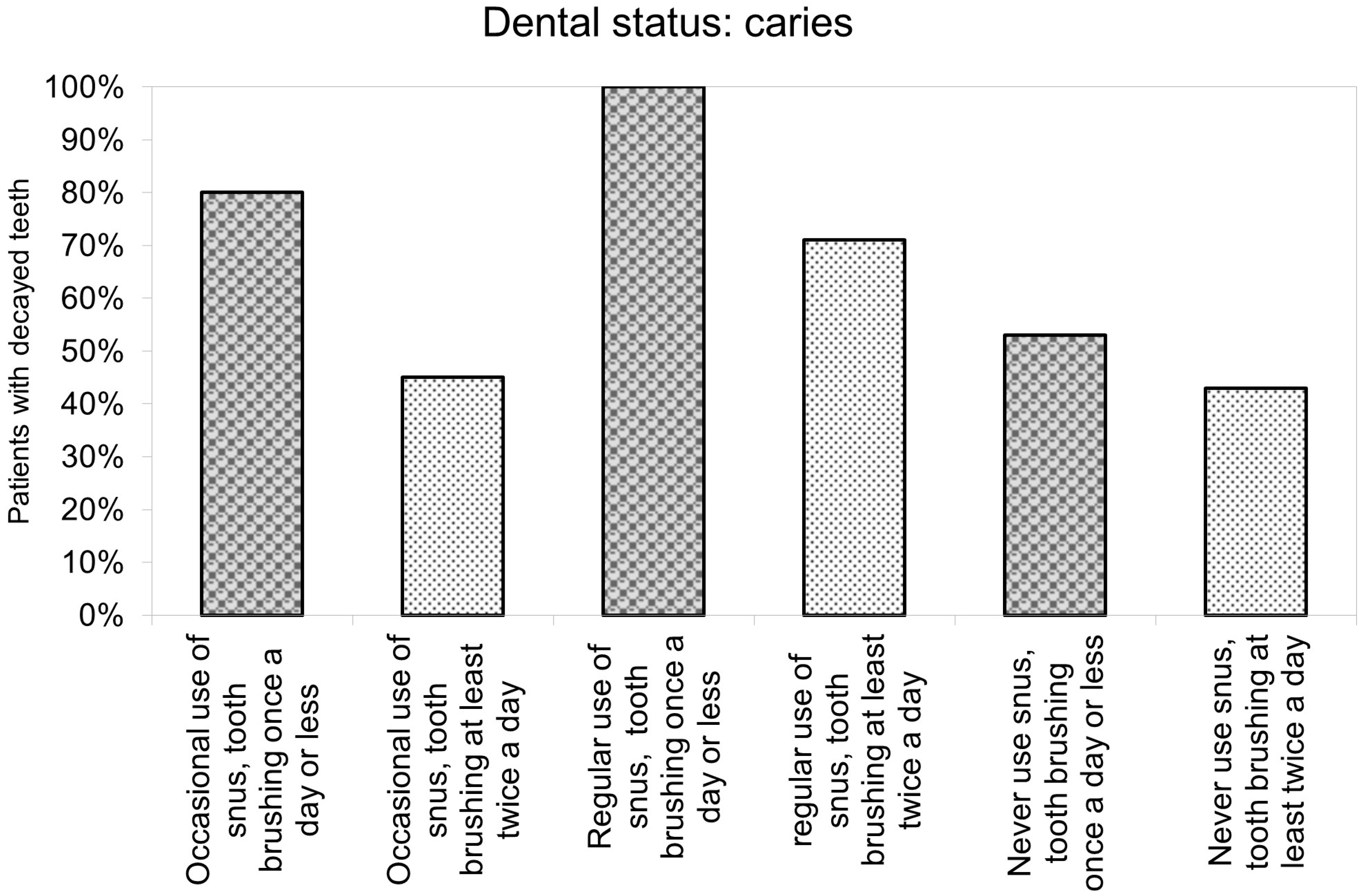

3.4. Oral Hygiene and Dental Status of Participants

3.5. Oral Effects of Snus

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Main Findings

4.2. Importance of Prevention in Periodontitis and Oral Cancer

4.3. Efficacy of Education

4.4. Special Population Characteristics

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

6. Bullet Points

- Snus use negatively affects oral health and is statistically significantly associated with gum bleeding.

- Insufficient oral hygiene and snus use cumulatively affect oral health, especially the gums.

- Awareness contributes to reducing snus usage; therefore, early childhood education has the leading role in prevention.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hatsukami, D.K.; Carroll, D.M. Tobacco harm reduction: Past history, current controversies and a proposed approach for the future. Prev. Med. 2020, 140, 106099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Digard, H.; Errington, G.; Richter, A.; McAdam, K. Patterns and behaviors of snus consumption in Sweden. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2009, 11, 1175–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.N. Epidemiological evidence relating snus to health—An updated review based on recent publications. Harm Reduct. J. 2013, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickworth, W.B.; Rosenberry, Z.R.; Gold, W.; Koszowski, B. Nicotine Absorption from Smokeless Tobacco Modified to Adjust pH. J. Addict. Res. Ther. 2014, 5, 1000184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.B.; Newton, C.; Tung, W.C.; Sun, Y.; Li, D.; Ossip, D.; Rahman, I. Classification, Perception, and Toxicity of Emerging Flavored Oral Nicotine Pouches. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.M.; Weke, A.; Holliday, R. Nicotine pouches: A review for the dental team. Br. Dent. J. 2023, 235, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowd, A.N.; Thrul, J.; Czaplicki, L.; Kennedy, R.D.; Moran, M.B.; Spindle, T.R. A Cross-Sectional Survey on Oral Nicotine Pouches: Characterizing Use-Motives, Topography, Dependence Levels, and Adverse Events. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2024, 26, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hukkanen, J.; Jacob, P., III; Benowitz, N.L. Metabolism and Disposition Kinetics of Nicotine. Pharmacol. Rev. 2005, 57, 79–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mühlig, S.; Hering, T.; Sandholzer, H. Smoking cessation and prevention—Update and selected results. Pneumologie 2013, 67, 332–336. [Google Scholar]

- The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Directive 2014/40/EU of the European Parliament and the Council of April 2014 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products and repealing Directive 2001/37/EC. Off. J. Eur. Union 2014, 127, 1–38. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014L0040&from=EN (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- Chapman, F.; McDermott, S.; Rudd, K.; Taverner, V.; Stevenson, M.; Chaudhary, N.; Reichmann, K.; Thompson, J.; Nahde, T.; O’connell, G. A randomised, open-label, cross-over clinical study to evaluate the pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and safety and tolerability profiles of tobacco-free oral nicotine pouches relative to cigarettes. Psychopharmacology 2022, 239, 2931–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, E.; Thompson, K.; Weaver, S.; Thompson, J.; O’Connell, G. Snus: A compelling harm reduction alternative to cigarettes. Harm Reduct. J. 2019, 16, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulds, J.; Ramstrom, L.; Burke, M.; Fagerström, K. Effect of smokeless tobacco (snus) on smoking and public health in Sweden. Tob. Control 2003, 12, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallischnigg, G.; Weitkunat, R.; Lee, P.N. Systematic review of the relation between smokeless tobacco and non-neoplastic oral diseases in Europe and the United States. BMC Oral Health 2008, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopperud, S.E.; Ansteinsson, V.; Mdala, I.; Becher, R.; Valen, H. Oral lesions associated with daily use of snus, a moist smokeless tobacco product. A cross-sectional study among Norwegian adolescents. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2023, 81, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthukrishnan, A.; Warnakulasuriya, S. Oral health consequences of smokeless tobacco use. Indian J. Med. Res. 2018, 148, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Javed, F.; Chotai, M.; Mehmood, A.; Almas, K. Oral mucosal disorders associated with habitual gutka usage: A review. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2010, 109, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, J.A.; Burt, B.A. Periodontal effects and dental caries associated with smokeless tobacco use. Public Health Rep. 1987, 102, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hugoson, A.; Rolandsson, M. Periodontal disease in relation to smoking and the use of Swedish snus: Epidemiological studies covering 20 years (1983–2003). J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011, 38, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnakulasuriya, S.; Dietrich, T.; Bornstein, M.M.; Peidró, E.C.; Preshaw, P.M.; Walter, C.; Wennström, J.L.; Bergström, J. Oral health risks of tobacco use and effects of cessation. Int. Dent. J. 2010, 60, 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2022. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Pearson, K.X. On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1900, 50, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A. On the Interpretation of χ2 from Contingency Tables, and the Calculation of P. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1922, 85, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlemann, H.R.; Son, S. Gingival sulcus bleeding--a leading symptom in initial gingivitis. Helv. Odontol. Acta 1971, 15, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Löe, H.; Theilade, E.; Jensen, S.B. Experimental Gingivitis in Man. J. Periodontol. 1965, 36, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapple, I.L.C.; Van der Weijden, F.; Doerfer, C.; Herrera, D.; Shapira, L.; Polak, D.; Madianos, P.; Louropoulou, A.; Machtei, E.; Donos, N.; et al. Primary prevention of periodontitis: Managing gingivitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42 (Suppl. S16), S71–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trombelli, L.; Farina, R.; Silva, C.O.; Tatakis, D.N. Plaque-induced gingivitis: Case definition and diagnostic considerations. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89 (Suppl. S1), S46–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, S.; Mealey, B.L.; Mariotti, A.; Chapple, I.L.C. Dental plaque-induced gingival conditions. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89 Suppl 1, S17–S27. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, N.P.; Schätzle, M.A.; Löe, H. Gingivitis as a risk factor in periodontal disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2009, 36 (Suppl. S10), 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löe, H.; Anerud, A.; Boysen, H.; Morrison, E. Natural history of periodontal disease in man. Rapid, moderate and no loss of attachment in Sri Lankan laborers 14 to 46 years of age. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1986, 13, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, R.C.; Kornman, K.S. The pathogenesis of human periodontitis: An introduction. Periodontol. 2000 1997, 14, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schätzle, M.; Löe, H.; Bürgin, W.; Ånerud, A.; Boysen, H.; Lang, N.P. Clinical course of chronic periodontitis. I. Role of gingivitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2003, 30, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Available online: https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/periodontal-disease (accessed on 24 September 2023).

- Olczak-Kowalczyk, D.; Gozdowski, D.; Kaczmarek, U. Oral Health in Polish Fifteen-year-old Adolescents. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2019, 17, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fan, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, J.; Huang, S. Epidemiology and associated factors of gingivitis in adolescents in Guangdong Province, Southern China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnakulasuriya, S.; Johnson, N.W.; van der Waal, I. Nomenclature and classification of potentially malignant disorders of the oral mucosa. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2007, 36, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilligan, G.; Piemonte, E.; Lazos, J.; Simancas, M.C.; Panico, R.; Warnakulasuriya, S. Oral squamous cell carcinoma arising from chronic traumatic ulcers. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero, P.H.; Patel, S.G. Cancer of the oral cavity. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 24, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, S.L.; Hirsch, J.M.; Larsson, P.A.; Saidi, J.; Osterdahl, B.G. Snuff-induced carcinogenesis: Effect of snuff in rats initiated with 4-nitroquinoline N-oxide. Cancer Res. 1989, 49, 3063–3069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roosaar, A.; Johansson, A.L.; Sandborgh-Englund, G.; Axéll, T.; Nyrén, O. Cancer and mortality among users and nonusers of snus. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 123, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenquist, K.; Wennerberg, J.; Schildt, E.-B.; Bladström, A.; Hansson, B.G.; Andersson, G. Use of Swedish moist snuff, smoking and alcohol consumption in the aetiology of oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. A population-based case-control study in southern Sweden. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005, 125, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffetta, P.; Aagnes, B.; Weiderpass, E.; Andersen, A. Smokeless tobacco use and risk of cancer of the pancreas and other organs. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 114, 992–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miluna, S.; Melderis, R.; Briuka, L.; Skadins, I.; Broks, R.; Kroica, J.; Rostoka, D. The Correlation of Swedish Snus, Nicotine Pouches and Other Tobacco Products with Oral Mucosal Health and Salivary Biomarkers. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, P.M.; Epstein, J.B. The oral effects of smokeless tobacco. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2000, 66, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barata, G.; Gama, S.; Jorge, J.; Goncalves, D. Engaging Engineering Students with Gamification. In Proceedings of the 2013 5th International Conference on Games and Virtual Worlds for Serious Applications (VS-GAMES), Poole, UK, 11–13 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guggenheimer, J. Implications of smokeless tobacco use in athletes. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 1991, 35, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel Roth, H.; Roth, A.B.; Liu, X. Health Risks of Smoking Compared to Swedish Snus. Inhal. Toxicol. 2005, 17, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, M.E.; Lugo, A.; Boffetta, P.; Gilmore, A.; Ross, H.; Schüz, J.; La Vecchia, C.; Gallus, S. Smokeless tobacco use in Sweden and other 17 European countries. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interactive Preventive Education | Questionnaire Administration | Individual Oral Screening | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topic | interactive presentation to build trust | an 83-question survey administration | oral screenings with dental instruments |

| Content | snus definition, legal aspects, effects on sports addiction, cessation strategies | socio-demographic status, oral hygiene habits, addictions, factors influencing snus use, current snus habits, adverse effects | data on teeth, gum bleeding, fluorosis, erosion, soft tissue lesions |

| Exercises | visual aids, interactive games | assessing the short-term effectiveness | informations about any pathological findings |

| Groups | grouped based on their snus use (regular users, occasional users, and non-users) | ||

| categorized participants by their oral hygiene habits |

| Overall | Occasional User | Regular User | Never Used Snus | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do your gums tend to bleed when brushing your teeth? | 244 (98%) | 0.040 | |||

| Yes | 91 (37%) | 9 (26%) | 12 (60%) | 70 (37%) | |

| No | 153 (63%) | 26 (74%) | 8 (40%) | 119 (63%) | |

| NA | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Study | Olczak-Kowalczyk et al. [35] | Fan et al. [36] | Németh et al. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample of study | Polish adolescents, 15 years old | Adolescents from Guangdong Province, Southern China | Ice hockey players and footballers, aged 12–20, mostly living in Hungarian urban area |

| Number of participants | Not specified | 1502 | 248 (206 males and 42 females) |

| Prevalence of gingival bleeding, signs of inflammation, and gingivitis (%) | 29.6% | 37.4% | Overall: 37% Regular snus users: 60% |

| Findings on oral hygiene | Many adolescents practiced regular tooth brushing, but interdental cleaning was less common | Infrequent tooth brushing and lack of interdental cleaning correlated with increased gingivitis rates | 15.8% brushed teeth once or less daily 14.2% used floss or interdental brushes. 48.2% used electric/manual toothbrushes |

| Prevalence of dental caries | A high prevalence of dental caries was reported, with a mean DMFT (Decayed, Missing, and Filled Teeth) index of 4.2 | Not specified | Prevalence of dental caries: 47.58% Healthy dentition: 32% |

| Risk factors of gingivitis | Poor oral hygiene Plaque accumulation Smoking Diabetes Stress Poor diet Genetic factors | Higher prevalence was associated with poor oral hygiene practices, socioeconomic status, and dietary habits. Risk factors: age, gender, family structure, mother’s education level, oral health knowledge and attitudes, and regional differences | Regular snus user Poor oral hygiene The combined effect of oral hygiene habits and snus usage |

| Suggested preventive measures | Targeted oral health interventions Better education on oral hygiene Increased access to dental care services | Targeted public health interventions to improve oral hygiene and address socioeconomic disparities | Enhanced educational and preventive measures to address the oral health risks associated with snus use |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Németh, O.; Sipos, L.; Mátrai, P.; Szathmári-Mészáros, N.; Iványi, D.; Simon, F.; Kivovics, M.; Pénzes, D.; Mijiritsky, E. Snus Use in Adolescents: A Threat to Oral Health. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4235. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13144235

Németh O, Sipos L, Mátrai P, Szathmári-Mészáros N, Iványi D, Simon F, Kivovics M, Pénzes D, Mijiritsky E. Snus Use in Adolescents: A Threat to Oral Health. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(14):4235. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13144235

Chicago/Turabian StyleNémeth, Orsolya, Levente Sipos, Péter Mátrai, Noémi Szathmári-Mészáros, Dóra Iványi, Fanni Simon, Márton Kivovics, Dorottya Pénzes, and Eitan Mijiritsky. 2024. "Snus Use in Adolescents: A Threat to Oral Health" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 14: 4235. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13144235

APA StyleNémeth, O., Sipos, L., Mátrai, P., Szathmári-Mészáros, N., Iványi, D., Simon, F., Kivovics, M., Pénzes, D., & Mijiritsky, E. (2024). Snus Use in Adolescents: A Threat to Oral Health. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(14), 4235. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13144235