Customized Scleral Lenses: An Alternative Tool for Severe Dry Eye Disease—A Case Series

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Scleral Lens

3. Materials and Methods

Customized Scleral Lenses

4. Case Series: Three Patients Affected by Severe Dry Eye Disease

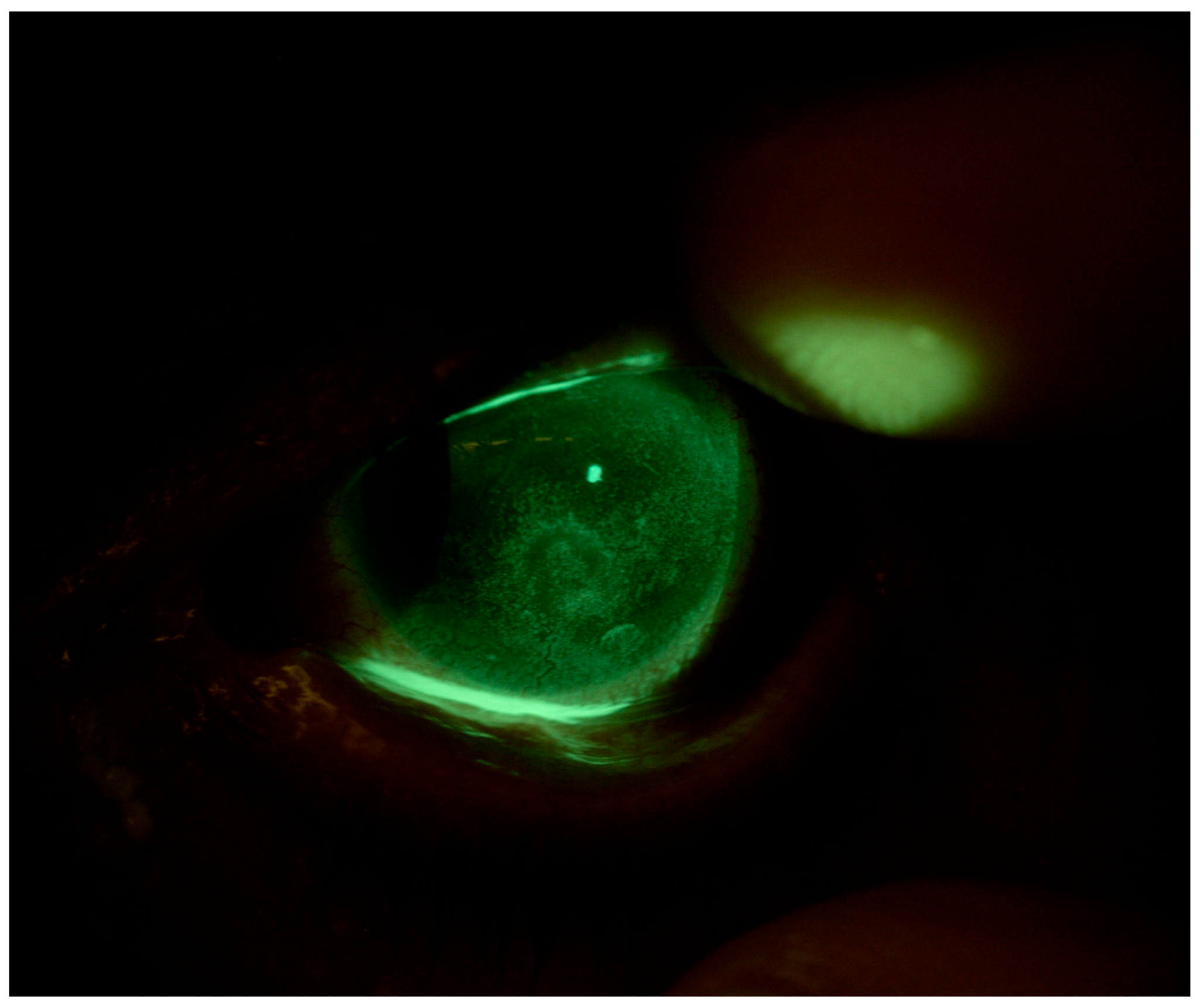

4.1. Patient 1

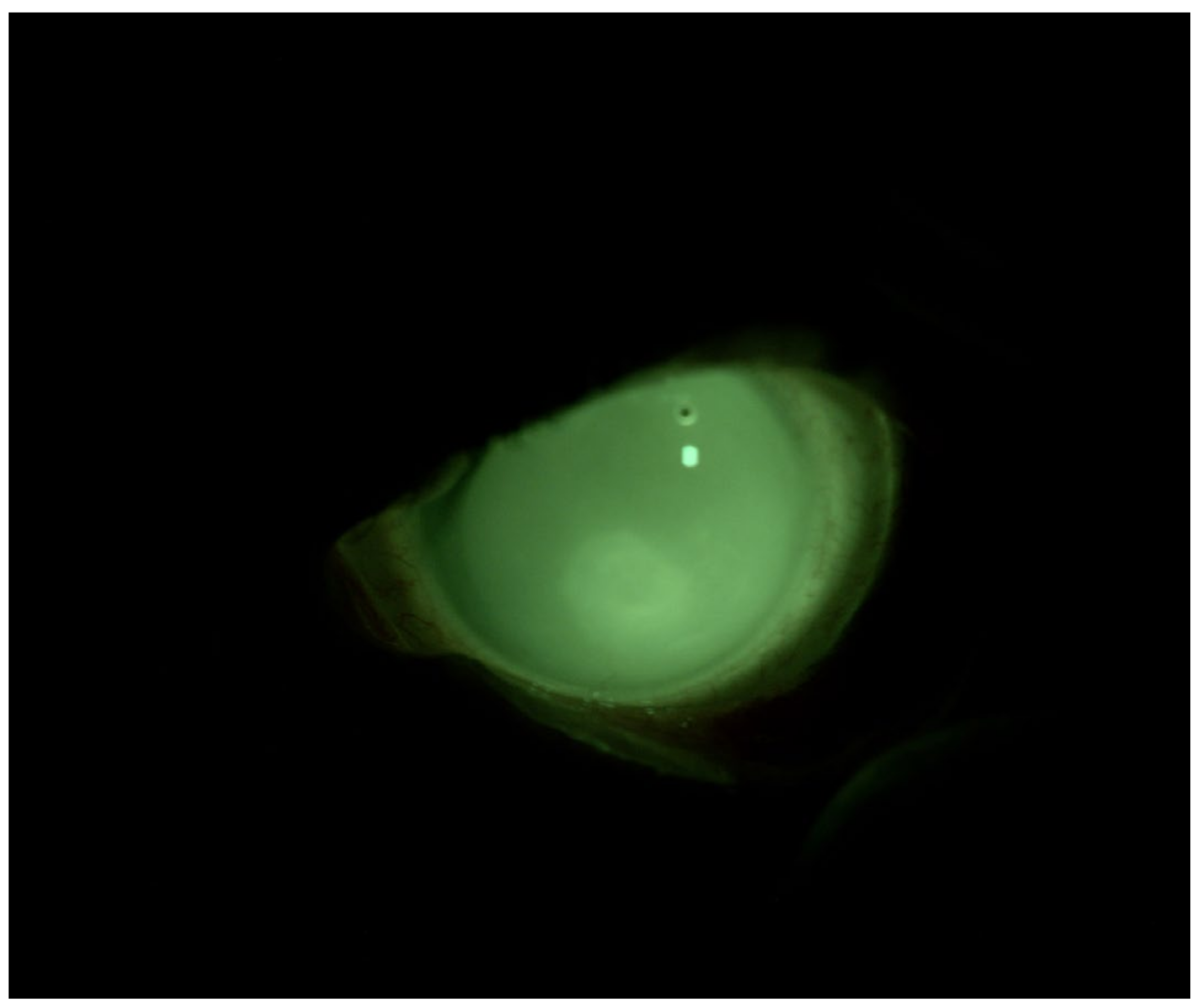

4.2. Patient 2

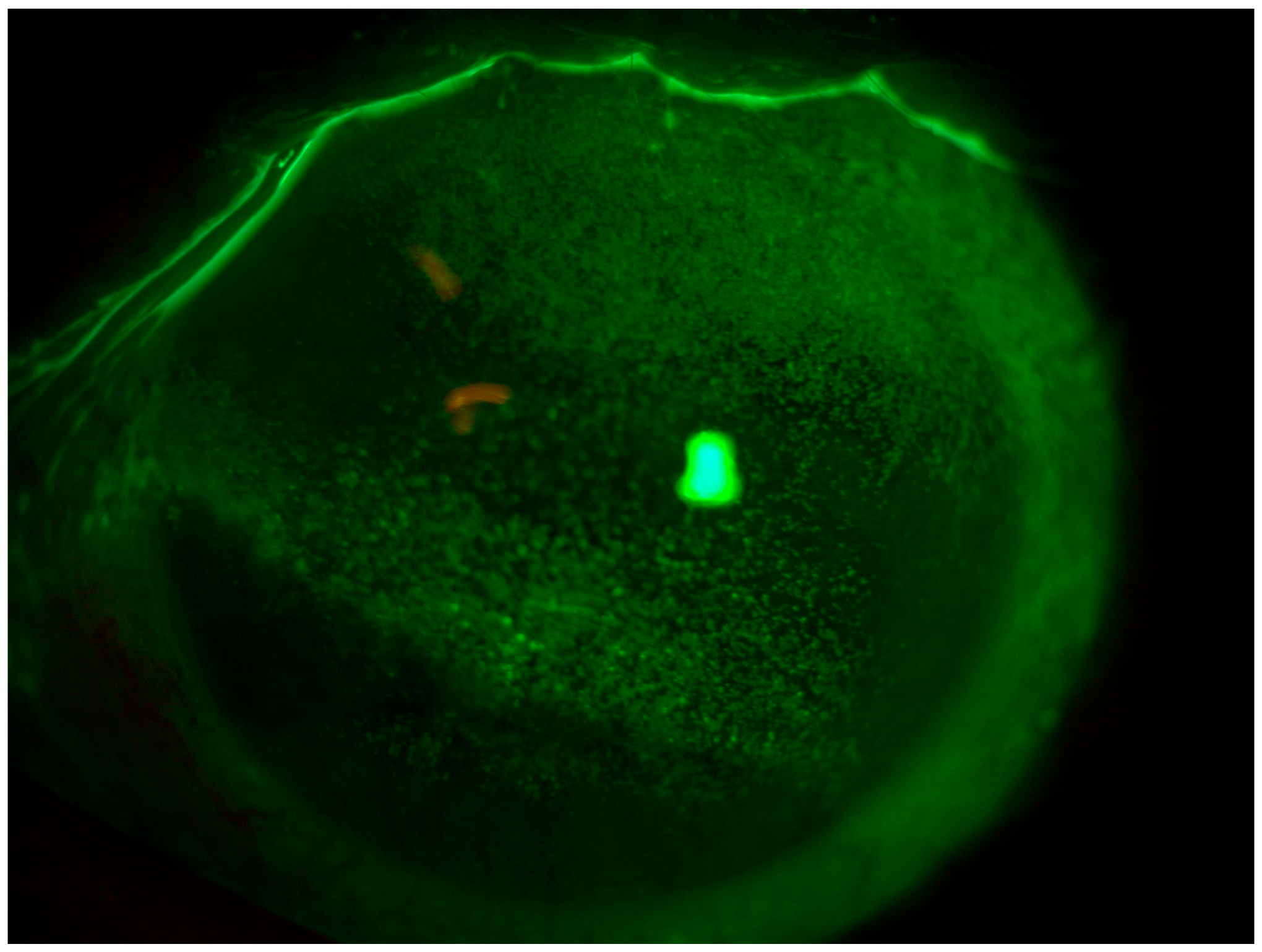

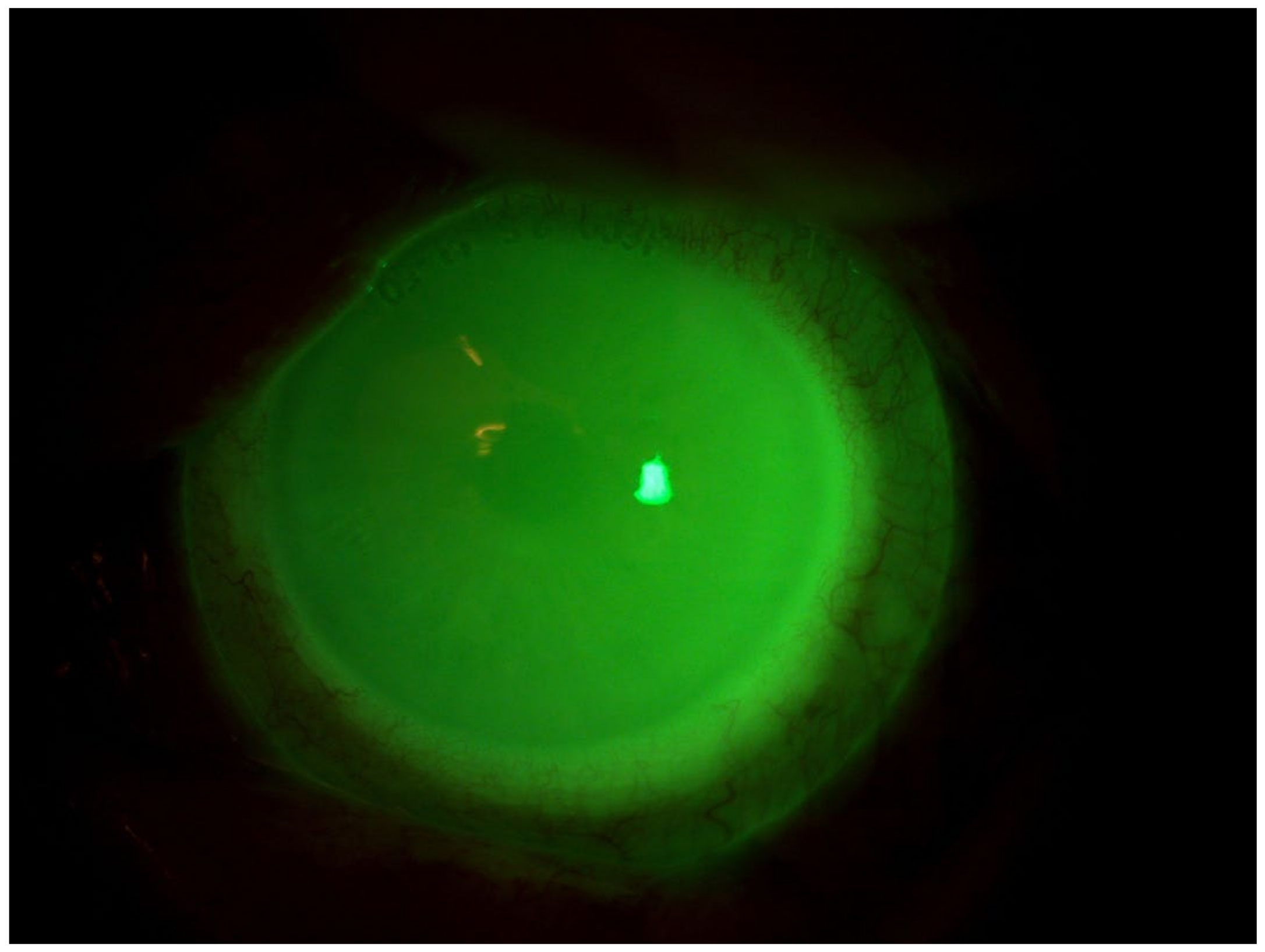

4.3. Patient 3

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Messmer, E.M. The Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Dry Eye Disease. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2015, 112, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calonge, M. The Treatment of Dry Eye. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2001, 45 (Suppl. S2), S227–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, J.P.; Nelson, J.D.; Azar, D.T.; Belmonte, C.; Bron, A.J.; Chauhan, S.K.; de Paiva, C.S.; Gomes, J.A.P.; Hammitt, K.M.; Jones, L.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Report Executive Summary. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, N.J. Impact of Dry Eye Disease and Treatment on Quality of Life. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2010, 21, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, K.H.; Chen, L.J.; Young, A.L. Depression and Anxiety in Dry Eye Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eye 2016, 30, 1558–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Wu, X.; Lin, X.; Lin, H. The Prevalence of Depression and Depressive Symptoms among Eye Disease Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Lv, H.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Wang, W. Characteristics of Symptoms Experienced by Persons with Dry Eye Disease While Driving in China. Eye 2017, 31, 1550–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Tilborg, M.M.; Murphy, P.J.; Evans, K.S. Impact of Dry Eye Symptoms and Daily Activities in a Modern Office. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2017, 94, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Llamas, S.; Paz-Ramos, A.K.; Marcos-Gonzalez, P.; Amparo, F.; Garza-Leon, M. Symptoms of Ocular Surface Disease in Construction Workers: Comparative Study with Office Workers. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020, 20, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, N.H.; Mather, R.; To, A.; Malvankar-Mehta, M.S. Sleep Outcomes Associated with Dry Eye Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 54, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.; Downie, L.E.; Korb, D.; Benitez-del-Castillo, J.M.; Dana, R.; Deng, S.X.; Dong, P.N.; Geerling, G.; Hida, R.Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Management and Therapy Report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 575–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Porta Weber, S.; Becco De Souza, R.; Gomes, J.Á.P.; Hofling-Lima, A.L. The Use of the Esclera Scleral Contact Lens in the Treatment of Moderate to Severe Dry Eye Disease. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 163, 167–173.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, F.; Kheirkhah, A.; Jabarvand Behrouz, M. Use of Mini Scleral Contact Lenses in Moderate to Severe Dry Eye. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 2012, 35, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tappin, M.J.; Pullum, K.W.; Buckley, R.J. Scleral Contact Lenses for Overnight Wear in the Management of Ocular Surface Disorders. Eye 2001, 15, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuksel, E.; Bilgihan, K.; Novruzlu, Ş.; Yuksel, N.; Koksal, M. The Management of Refractory Dry Eye with Semi-Scleral Contact Lens. Eye Contact Lens 2018, 44, E10–E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimit, R.; Gire, A.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; Bergmanson, J.P.G. Patient Ocular Conditions and Clinical Outcomes Using a PROSE Scleral Device. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 2013, 36, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thulasi, P.; Djalilian, A.R. Update in Current Diagnostics and Therapeutics of Dry Eye Disease. Ophthalmology 2017, 124, S27–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schornack, M.M. Scleral Lenses: A Literature Review. Eye Contact Lens 2015, 41, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavinger, J.C.; DeLoss, K.; Mian, S.I. Scleral Lens Use in Dry Eye Syndrome. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2015, 26, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrupi, F.; De Luca, A.; Di Zazzo, A.; Micera, A.; Coassin, M.; Bonini, S. Real Life Impact of Dry Eye Disease. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2023, 38, 690–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, V.M.; Mandathara, P.S.; Vaddavalli, P.K.; Srikanth, D.; Sangwan, V.S. Fluid Filled Scleral Contact Lens in Pediatric Patients: Challenges and Outcome. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 2012, 35, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, D.; Collins, M.J.; Vincent, S.J. Conjunctival Prolapse during Open Eye Scleral Lens Wear. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 2021, 44, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.H.; Tan, B.; Lin, M.C.; Radke, C.J. Central Corneal Edema with Scleral-Lens Wear. Curr. Eye Res. 2018, 43, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, M.; Sharma, S. Polymicrobial and Microsporidial Keratitis in a Patient Using Boston Scleral Contact Lens for Sjogren’s Syndrome and Ocular Cicatricial Pemphigoid. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 2013, 36, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhat, B.; Sutphin, J.E. Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty for Acanthamoeba Keratitis Complicating the Use of Boston Scleral Lens. Eye Contact Lens 2014, 40, e5–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadel, D. Scleral Lens Issues and Complications Related to a Non-Optimal Fitting Relationship Between the Lens and Ocular Surface. Eye Contact Lens 2019, 45, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medical Applications of Scleral Contact Lenses: 1. A Retrospective Analysis of 343 Cases. PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7743792/ (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Chiu, G.B.; Bach, D.; Theophanous, C.; Heur, M. Prosthetic Replacement of the Ocular Surface Ecosystem (PROSE) Scleral Lens for Salzmann’s Nodular Degeneration. Saudi J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 28, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harthan, J.S. Therapeutic Use of Mini-Scleral Lenses in a Patient with Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. J. Optom. 2014, 7, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, D.S.; Rosenthal, P. Boston Scleral Lens Prosthetic Device for Treatment of Severe Dry Eye in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Cornea 2007, 26, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schornack, M.M.; Baratz, K.H.; Patel, S.V.; Maguire, L.J. Jupiter Scleral Lenses in the Management of Chronic Graft versus Host Disease. Eye Contact Lens 2008, 34, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahide, K.; Parker, P.M.; Wu, M.; Hwang, W.Y.K.; Carpenter, P.A.; Moravec, C.; Stehr, B.; Martin, P.J.; Rosenthal, P.; Forman, S.J.; et al. Use of Fluid-Ventilated, Gas-Permeable Scleral Lens for Management of Severe Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca Secondary to Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007, 13, 1016–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schornack, M.M.; Pyle, J.; Patel, S.V. Scleral Lenses in the Management of Ocular Surface Disease. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 1398–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arumugam, A.O.; Rajan, R.; Subramanian, M.; Mahadevan, R. PROSE for Irregular Corneas at a Tertiary Eye Care Center. Eye Contact Lens 2014, 40, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Rangel, T.; Stavrou, P.; Cotter, J.; Rosenthal, P.; Baltatzis, S.; Foster, C.S. Gas-Permeable Scleral Contact Lens Therapy in Ocular Surface Disease. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2000, 130, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visser, E.S.; Visser, R.; Van Lier, H.J.J.; Otten, H.M. Modern Scleral Lenses Part I: Clinical Features. Eye Contact Lens 2007, 33, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, S.; Ghimire, D.; Basu, S.; Agrawal, V.; Jacobs, D.S.; Shanbhag, S.S. Contact Lenses in Dry Eye Disease and Associated Ocular Surface Disorders. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 71, 1142–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nunziata, S.; Petrini, D.; Dell’Anno, S.; Barone, V.; Coassin, M.; Di Zazzo, A. Customized Scleral Lenses: An Alternative Tool for Severe Dry Eye Disease—A Case Series. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3935. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133935

Nunziata S, Petrini D, Dell’Anno S, Barone V, Coassin M, Di Zazzo A. Customized Scleral Lenses: An Alternative Tool for Severe Dry Eye Disease—A Case Series. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(13):3935. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133935

Chicago/Turabian StyleNunziata, Sebastiano, Daniele Petrini, Serena Dell’Anno, Vincenzo Barone, Marco Coassin, and Antonio Di Zazzo. 2024. "Customized Scleral Lenses: An Alternative Tool for Severe Dry Eye Disease—A Case Series" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 13: 3935. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133935

APA StyleNunziata, S., Petrini, D., Dell’Anno, S., Barone, V., Coassin, M., & Di Zazzo, A. (2024). Customized Scleral Lenses: An Alternative Tool for Severe Dry Eye Disease—A Case Series. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(13), 3935. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133935