Step-Up versus Open Approach in the Treatment of Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis: A Case-Matched Analysis of Clinical Outcomes and Long-Term Pancreatic Sufficiency

Abstract

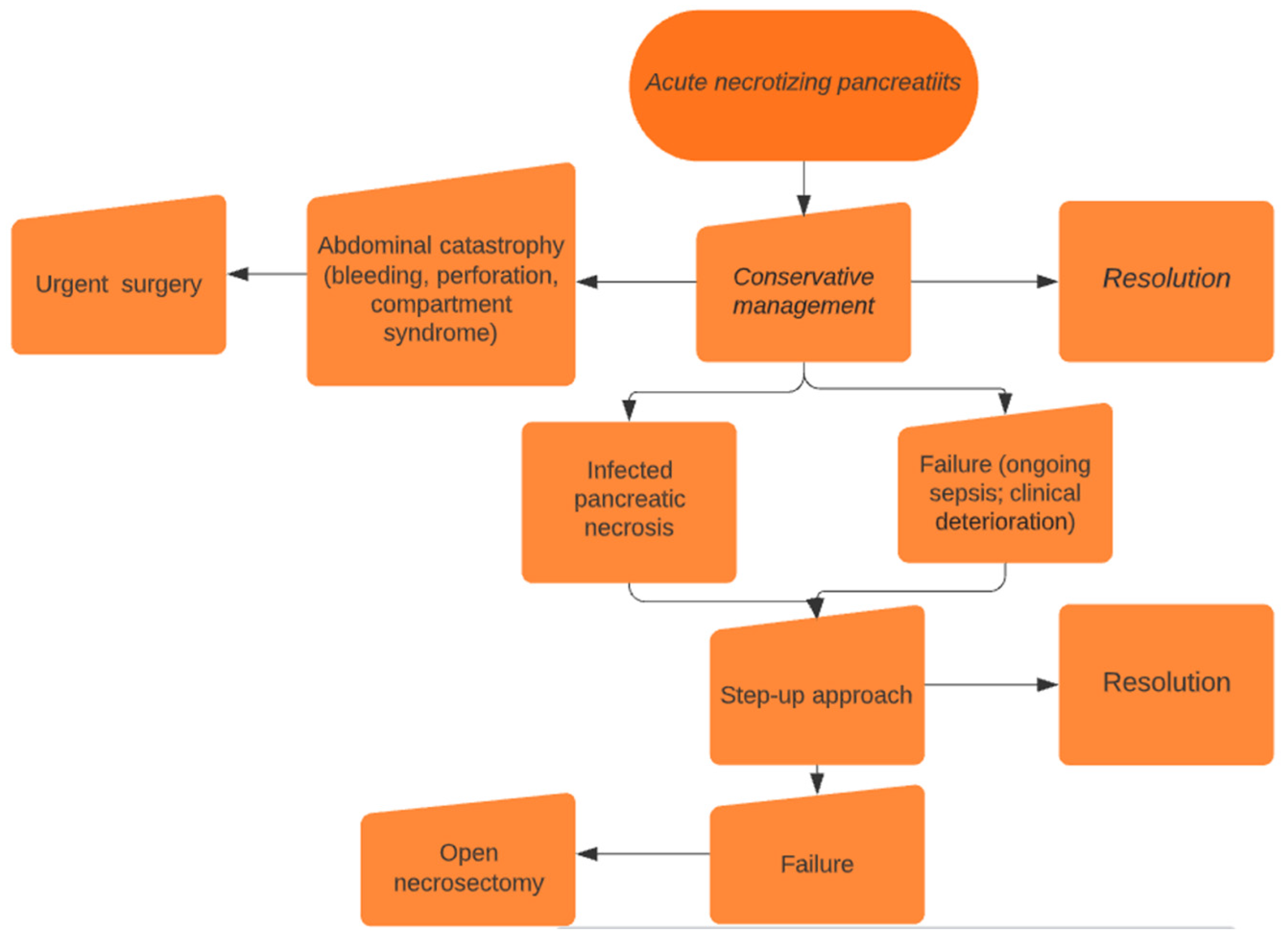

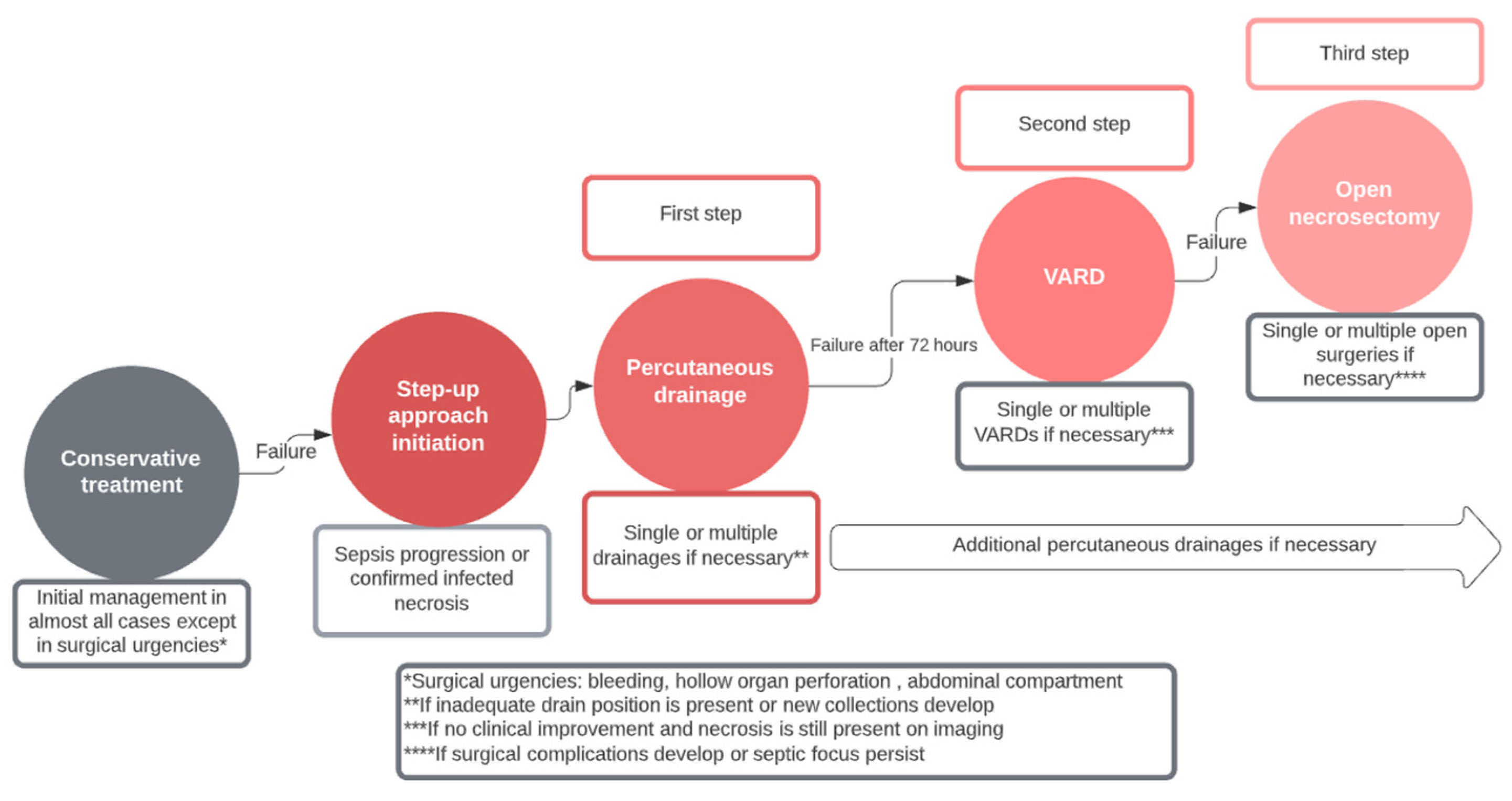

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Participants

3.2. Clinical Endpoints

3.3. Step-Up Approach Group

3.4. Open Necrosectomy Group

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leonard-Murali, S.; Lezotte, J.; Kalu, R.; Blyden, D.J.; Patton, J.H.; Johnson, J.L.; Gupta, A.H. Necrotizing Pancreatitis: A Review for the Acute Care Surgeon. Am. J. Surg. 2021, 221, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Santvoort, H.C.; Besselink, M.G.; Bakker, O.J.; Hofker, H.S.; Boermeester, M.A.; Dejong, C.H.; Van Goor, H.; Schaapherder, A.F.; Van Eijck, C.H.; Bollen, T.L.; et al. A Step-up Approach or Open Necrosectomy for Necrotizing Pancreatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1491–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miskovitz, P. A Step-Up Approach to Managing Acute Pancreatitis–Associated Fluid Collections. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 43, 244–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, T.H.; DiMaio, C.J.; Wang, A.Y.; Morgan, K.A. American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Update: Management of Pancreatic Necrosis. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 67–75.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, J.Y.; Arnoletti, J.P.; Holt, B.A.; Sutton, B.; Hasan, M.K.; Navaneethan, U.; Feranec, N.; Wilcox, C.M.; Tharian, B.; Hawes, R.H.; et al. An Endoscopic Transluminal Approach, Compared with Minimally Invasive Surgery, Reduces Complications and Costs for Patients with Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1027–1040.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.D.; Clark, C.J.; Dyer, R.; Case, L.D.; Mishra, G.; Pawa, R. Analysis of a Step-Up Approach Versus Primary Open Surgical Necrosectomy in the Management of Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Pancreas 2018, 47, 1317–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Brunschot, S.; Van Grinsven, J.; Van Santvoort, H.C.; Bakker, O.J.; Besselink, M.G.; Boermeester, M.A.; Bollen, T.L.; Bosscha, K.; Bouwense, S.A.; Bruno, M.J.; et al. Endoscopic or Surgical Step-up Approach for Infected Necrotising Pancreatitis: A Multicentre Randomised Trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wundsam, H.V.; Spaun, G.O.; Bräuer, F.; Schwaiger, C.; Fischer, I.; Függer, R. Evolution of Transluminal Necrosectomy for Acute Pancreatitis to Stent in Stent Therapy: Step-up Approach Leads to Low Mortality and Morbidity Rates in 302 Consecutive Cases of Acute Pancreatitis. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. Part A 2019, 29, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxhoorn, L.; Van Dijk, S.M.; Van Grinsven, J.; Verdonk, R.C.; Boermeester, M.A.; Bollen, T.L.; Bouwense, S.A.W.; Bruno, M.J.; Cappendijk, V.C.; Dejong, C.H.C.; et al. Immediate versus Postponed Intervention for Infected Necrotizing Pancreatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckhurst, C.M.; Hechi, M.E.; Elsharkawy, A.E.; Eid, A.I.; Maurer, L.R.; Kaafarani, H.M.; Thabet, A.; Forcione, D.G.; Castillo, C.F.-D.; Lillemoe, K.D.; et al. Improved Mortality in Necrotizing Pancreatitis with a Multidisciplinary Minimally Invasive Step-Up Approach: Comparison with a Modern Open Necrosectomy Cohort. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2020, 230, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, S.; Wang, P.; Feng, J.; He, L.; Du, J.; Xiao, Y.; Jiao, H.; Zhou, F.; Song, Q.; et al. Minimal-Access Retroperitoneal Pancreatic Necrosectomy for Infected Necrotizing Pancreatitis: A Multicentre Study of a Step-up Approach. Br. J. Surg. 2020, 107, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sion, M.K.; Davis, K.A. Step-up Approach for the Management of Pancreatic Necrosis: A Review of the Literature. Trauma Surg. Acute Care Open 2019, 4, e000308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besselink, M.G.H.; Van Santvoort, H.C.; Nieuwenhuijs, V.B.; Boermeester, M.A.; Bollen, T.L.; Buskens, E.; Dejong, C.H.C.; Van Eijck, C.H.J.; Van Goor, H.; Hofker, S.S.; et al. Minimally Invasive “step-up Approach” versus Maximal Necrosectomy in Patients with Acute Necrotising Pancreatitis (PANTER Trial): Design and Rationale of a Randomised Controlled Multicenter Trial [ISRCTN13975868]. BMC Surg. 2006, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.-A. Classification of Surgical Complications. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassi, C.; Dervenis, C.; Butturini, G.; Fingerhut, A.; Yeo, C.; Izbicki, J.; Neoptolemos, J.; Sarr, M.; Traverso, W.; Buchler, M. Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula: An International Study Group (ISGPF) Definition. Surgery 2005, 138, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasparoto, R.C.G.W.; De Castro Jorge Racy, M.; De Campos, T. Long-Term Outcomes after Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis: What Happens to the Pancreas and to the Patient? J. Pancreas 2015, 16, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trikudanathan, G.; Wolbrink, D.R.J.; Van Santvoort, H.C.; Mallery, S.; Freeman, M.; Besselink, M.G. Current Concepts in Severe Acute and Necrotizing Pancreatitis: An Evidence-Based Approach. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1994–2007.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempeneers, M.A.; Besselink, M.G.; Issa, Y.; Van Hooft, J.E.; Van Goor, H.; Bruno, M.J.; Van Santvoort, H.C.; Boermeester, M.A. Multidisciplinary Treatment of Chronic Pancreatitis: An Overview of Current Step-up Approach and New Options. Ned. Tijdschr. Voor Geneeskd. 2017, 161, D1454. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S.; Padhan, R.; Bopanna, S.; Jain, S.K.; Dhingra, R.; Dash, N.R.; Madhusudan, K.S.; Gamanagatti, S.R.; Sahni, P.; Garg, P.K. Percutaneous Endoscopic Step-Up Therapy Is an Effective Minimally Invasive Approach for Infected Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 65, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaramurthi, S.; Kannan, A.; Nagarajan, R.; Dasarathan, S.; Dharanipragada, K. Precise Pancreatic Necrosectomy by Step-up Approach. EXCLI J. 2021, 20, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, L.R.; Maatman, T.K.; Luckhurst, C.M.; Horvath, K.D.; Zyromski, N.J.; Fagenholz, P.J. Risk of Gallstone-Related Complications in Necrotizing Pancreatitis Patients Treated with a Step-up Approach: The Experience of Two Tertiary Care Centers. Surgery 2021, 169, 1086–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, C.; Di Saverio, S.; Sartelli, M.; Segallini, E.; Cilloni, N.; Pezzilli, R.; Pagano, N.; Gomes, F.; Catena, F. Severe Acute Pancreatitis: Eight Fundamental Steps Revised according to the ‘PANCREAS’ Acronym. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2020, 102, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Costa, D.W.; Boerma, D.; Van Santvoort, H.C.; Horvath, K.D.; Werner, J.; Carter, C.R.; Bollen, T.L.; Gooszen, H.G.; Besselink, M.G.; Bakker, O.J. Staged Multidisciplinary Step-up Management for Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Br. J. Surg. 2013, 101, e65–e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Lu, J.-D.; Ding, Y.-X.; Guo, Y.-L.; Mei, W.-T.; Qu, Y.-X.; Cao, F.; Li, F. Comparison of Safety, Efficacy, and Long-Term Follow-up between “One-Step” and “Step-up” Approaches for Infected Pancreatic Necrosis. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2021, 13, 1372–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morató, O.; Poves, I.; Ilzarbe, L.; Radosevic, A.; Vázquez-Sánchez, A.; Sánchez-Parrilla, J.; Burdío, F.; Grande, L. Minimally Invasive Surgery in the Era of Step-up Approach for Treatment of Severe Acute Pancreatitis. Int. J. Surg. 2018, 51, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparna, D.; Kumar, S.; Kamalkumar, S. Mortality and Morbidity in Necrotizing Pancreatitis Managed on Principles of Step-up Approach: 7 Years Experience from a Single Surgical Unit. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2017, 9, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, F.; Duan, N.; Gao, C.; Li, A.; Li, F. One-Step Verse Step-Up Laparoscopic-Assisted Necrosectomy for Infected Pancreatic Necrosis. Dig. Surg. 2019, 37, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Lu, Z.; Li, Q.; Jiang, K.; Wu, J.; Gao, W.; Miao, Y. A Risk Score for Predicting the Necessity of Surgical Necrosectomy in the Treatment of Infected Necrotizing Pancreatitis. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2023, 27, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, S.C.; Martinez, A.V.; Sánchez, T.G.; Aguilar, A.F.; García, J.M.P. Step-up Approach in Severe Necrotizing Pancreatitis: Combination of Video-Assisted Retroperitoneal Debridement and Endoscopic Necrosectomy. Cirugía Española 2022, 100, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Step Up Approach | Open Necrosectomy | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 61.2 ± 2.3 | 62.4 ± 2.2 | 0.86 |

| Male gender (n, %) | 13 (65) | 28 (70) | 0.69 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26 (23–28) | 27 (23–29) | 0.92 |

| Ranson score, mean (±SD) | 1.64 (±0.82) | 1.67 (±0.91) | 0.50 |

| Etiology of ANP | |||

| 11 (55) | 26 (65) | |

| 6 (30) | 10 (25) | 0.71 |

| 3 (15) | 4 (10) | |

| Apache II score | 15.1 (±5.2) | 15.9 (5.9) | 0.71 |

| CT severity index | |||

| <50% | 14 | 30 | 0.56 |

| >50% | 6 | 10 | |

| Time from diagnosis to intervention, days (range) | 29 (18–59) | 32 (17–82) | 0.08 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| 9 | 26 | 0.59 |

| 3 | 5 | 0.32 |

| 2 | 5 | 0.9 |

| ASA score | |||

| 13 | 28 | 0.77 |

| 7 | 2 | |

| Serum lipase levels, U/l (± SD) | 2456 (±2336) | 2650 (±2211) | 0.39 |

| Leukocytes/mm3 | 18,096 (±9069) | 19,244 (±8066) | 0.44 |

| Confirmed infected necrosis n (%) | 18 (90) | 36 (87.5) | 1.0 |

| Microbiological isolates | |||

| E. coli | 8 | 16 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 4 | 8 | |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 3 | 5 | |

| Pseudomonas aureginosa | 2 | 5 | |

| Enterococcum faecium | 1 | 3 | |

| Other | 2 | 3 |

| Category | Step Up Approach | Open Necrosectomy | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality, n (%) | 4 (20) | 11 (27.5) | 0.53 |

| Major morbidity, n (%) | 7 (35) | 24 (60) | 0.044 |

| 3 | 8 | |

| 1 | 4 | |

| 0 | 2 | |

| 3 | 6 | |

| Pancreatic insufficiency, n (%) | 4 (20) | 19 (47.5) | 0.038 |

| 3 | 13 | |

| 1 | 4 | |

| 0 | 2 | |

| Hospital stay, median (range) | 42 (9–212) | 51 (22–255) | 0.44 |

| ICU stay, median (range) | 11 (2–96) | 13 (4–113) | 0.37 |

| Pancreatic fistula, n (%) | 5 (25) | 17 (42.5) | |

| 2 | 8 | 0.18 |

| 1 | 5 | |

| 2 | 4 | |

| Number of interventions per group | |||

| 32 | 96 | 0.04 |

| 21 | 79 |

| Group | Percutaneous Drainage Only | Percutaneous Drainage + VARD Only | Percutaneous Drainage + VARD + Open Necrosectomy | Percutaneous Drainage + Open Necrosectomy | ||||

| Single | Multiple | Single VARD | Multiple VARDs | Single necrosectomy | Multiple necrosectomies | Single | Multiple | |

| Step-up approach | 5 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Group | Single Open Necrosectomy | Multiple Open Necrosectomies | Additional Percutaneous Drainage | Additional Surgery for Complications | ||||

| 2 | >2 | Single | Multiple | Single | Multiple | |||

| Open necrosectomy | 24 | 10 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 3 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pavlek, G.; Romic, I.; Kekez, D.; Zedelj, J.; Bubalo, T.; Petrovic, I.; Deban, O.; Baotic, T.; Separovic, I.; Strajher, I.M.; et al. Step-Up versus Open Approach in the Treatment of Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis: A Case-Matched Analysis of Clinical Outcomes and Long-Term Pancreatic Sufficiency. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3766. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133766

Pavlek G, Romic I, Kekez D, Zedelj J, Bubalo T, Petrovic I, Deban O, Baotic T, Separovic I, Strajher IM, et al. Step-Up versus Open Approach in the Treatment of Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis: A Case-Matched Analysis of Clinical Outcomes and Long-Term Pancreatic Sufficiency. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(13):3766. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133766

Chicago/Turabian StylePavlek, Goran, Ivan Romic, Domina Kekez, Jurica Zedelj, Tomislav Bubalo, Igor Petrovic, Ognjan Deban, Tomislav Baotic, Ivan Separovic, Iva Martina Strajher, and et al. 2024. "Step-Up versus Open Approach in the Treatment of Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis: A Case-Matched Analysis of Clinical Outcomes and Long-Term Pancreatic Sufficiency" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 13: 3766. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133766

APA StylePavlek, G., Romic, I., Kekez, D., Zedelj, J., Bubalo, T., Petrovic, I., Deban, O., Baotic, T., Separovic, I., Strajher, I. M., Bicanic, K., Pavlek, A. E., Silic, V., Tolic, G., & Silovski, H. (2024). Step-Up versus Open Approach in the Treatment of Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis: A Case-Matched Analysis of Clinical Outcomes and Long-Term Pancreatic Sufficiency. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(13), 3766. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133766