Headache and Associated Psychological Variables in Intensive Care Unit Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Prospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

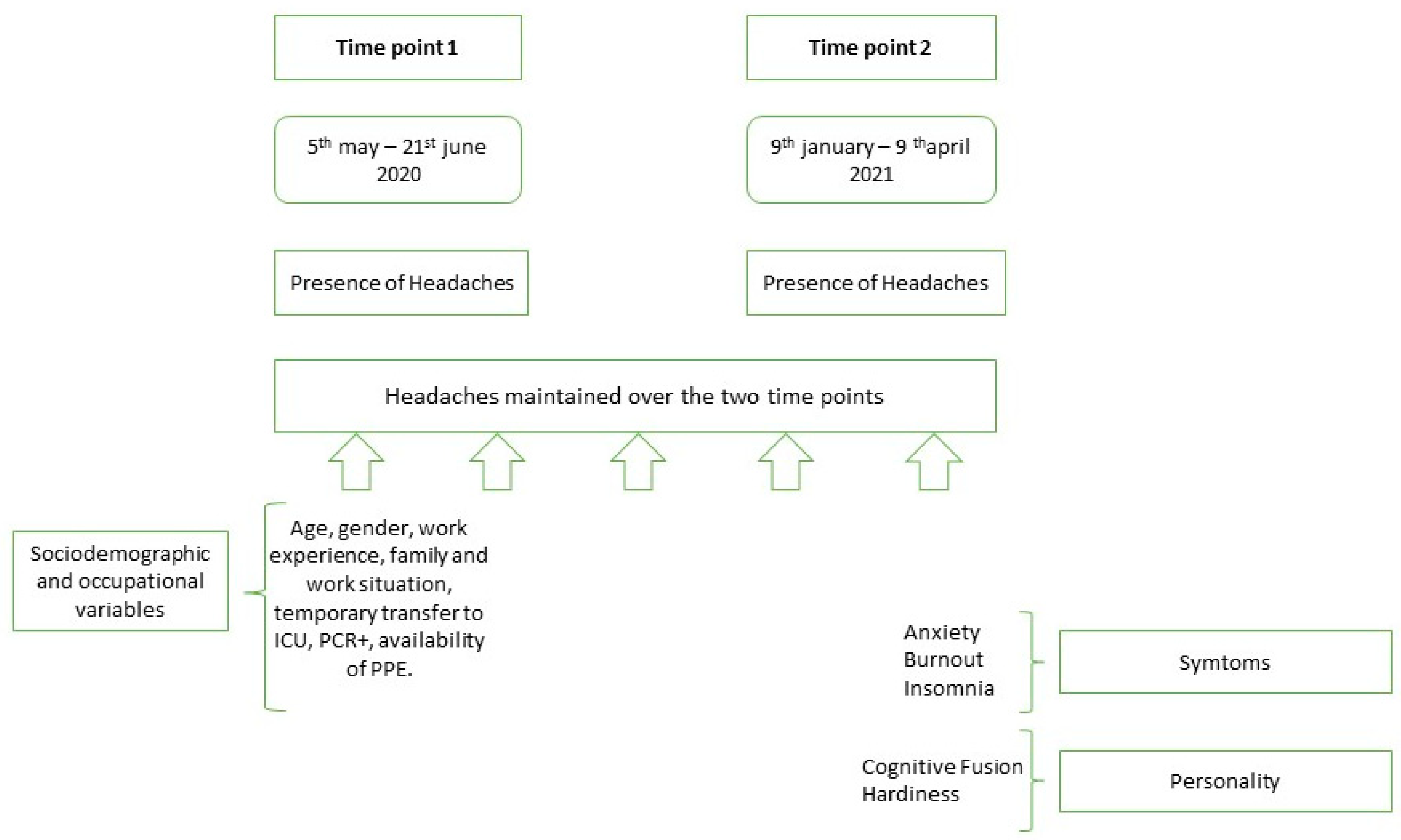

2.1. Design

2.2. Population and Sampling

2.3. Variables and Instruments

2.3.1. Presence of Headache [Time Point 1 and 2]

2.3.2. Sociodemographic and Occupational Variables [Time Point 1]

2.3.3. Variables Related to Symptoms [Time Point 2]

- (a)

- Anxiety

- (b)

- Insomnia

- (c)

- Burnout

2.3.4. Personality-Related Variables [Time Point 2]

- (a)

- Cognitive Fusion

- (b)

- Hardiness

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. Prevalence of Headaches and Their Evolution over Time (Chronic Headaches)

3.3. Relationship of Headaches with Sociodemographic and Occupational Variables

3.4. Associations between Headache Maintenance, Symptoms (Anxiety, Burnout, Insomnia) and Personality (Cognitive Fusion and Hardiness)

3.4.1. Symptoms

3.4.2. Personality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bushman, E.T.; Varner, M.W.; Digre, K.B. Headaches Through a Woman’s Life. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2018, 73, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, G.P.A.; Fracarolli, I.F.L.; Dos Santos, H.E.C.; de Oliveira, S.A.; Martins, B.G.; Junior, L.J.S.; Marziale, M.H.P.; Rocha, F.L.R. Depression, Anxiety and Stress in Health Professionals in the COVID-19 Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, J. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: History and Future Perspectives. Cephalalgia 2024, 44, 03331024231214731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, J.; Yang, F.; Wu, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Deng, X.; Yu, S. The Prevalence of Primary Headache Disorders and Their Associated Factors among Nursing Staff in North China. J. Headache Pain 2015, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjorvatn, B.; Pallesen, S.; Moen, B.E.; Waage, S.; Kristoffersen, E.S. Migraine, Tension-Type Headache and Medication-Overuse Headache in a Large Population of Shift Working Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study in Norway. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onwuekwe, I.; Onyeka, T.; Aguwa, E.; Ezeala-Adikaibe, B.; Ekenze, O.; Onuora, E. Headache Prevalence and Its Characterization amongst Hospital Workers in Enugu, South East Nigeria. Head Face Med. 2014, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, G.; Ginszt, M.; Zawadka, M.; Rutkowska, K.; Podstawka, Z.; Szkutnik, J.; Majcher, P.; Gawda, P. The relationship between stress and masticatory muscle activity in female students. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, D.P.; Rocha, L.P.; de Pinho, E.C.; Tomaschewski-Barlem, J.G.; Barlem, E.L.D.; Goulart, L.S. Workloads and Burnout of Nursing Workers. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2019, 72, 1435–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadaoka, T.; Kanda, H.; Oiji, A.; Morioka, Y.; Kashiwakura, M.; Totsuka, S. Headache and Stress in a Group of Nurses and Government Administrators in Japan. Headache 1997, 37, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, D.; Minors, D.S.; Waterhouse, J.M. Shiftwork, Helplessness and Depression. J. Affect. Disord. 1993, 29, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Vela, B.; Jesús Llorente-Cantarero, F.; Henarejos-Alarcón, S.; Martínez-Rodríguez, A. Psychosocial and Physiological Risks of Shift Work in Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 26, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnell, S.; Dawson, D. “It’s Not like the Wards”. Experiences of Nurses New to Critical Care: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2006, 43, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magro-Morillo, A.; Boulayoune-Zaagougui, S.; Cantón-Habas, V.; Molina-Luque, R.; Hernández-Ascanio, J.; Ventura-Puertos, P.E. Emotional Universe of Intensive Care Unit Nurses from Spain and the United Kingdom: A Hermeneutic Approach. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2020, 59, 102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, J.J.Y.; Chan, A.C.Y.; Bharatendu, C.; Teoh, H.L.; Chan, Y.C.; Sharma, V.K. Headache Related to PPE Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2021, 25, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, J.J.Y.; Bharatendu, C.; Goh, Y.; Tang, J.Z.Y.; Sooi, K.W.X.; Tan, Y.L.; Tan, B.Y.Q.; Teoh, H.-L.; Ong, S.T.; Allen, D.M.; et al. Headaches Associated With Personal Protective Equipment—A Cross-Sectional Study Among Frontline Healthcare Workers during COVID-19. Headache 2020, 60, 864–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapisarda, L.; Trimboli, M.; Fortunato, F.; De Martino, A.; Marsico, O.; Demonte, G.; Augimeri, A.; Labate, A.; Gambardella, A. Facemask Headache: A New Nosographic Entity among Healthcare Providers in COVID-19 Era. Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2021, 42, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Köseoğlu Toksoy, C.; Demirbaş, H.; Bozkurt, E.; Acar, H.; Türk Börü, Ü. Headache Related to Mask Use of Healthcare Workers in COVID-19 Pandemic. Korean J. Pain 2021, 34, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekizoglu, E.; Gezegen, H.; Yalınay Dikmen, P.; Orhan, E.K.; Ertaş, M.; Baykan, B. The Characteristics of COVID-19 Vaccine-Related Headache: Clues Gathered from the Healthcare Personnel in the Pandemic. Cephalalgia 2022, 42, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasergivehchi, S.; Togha, M.; Jafari, E.; Sheikhvatan, M.; Shahamati, D. Headache Following Vaccination against COVID-19 among Healthcare Workers with a History of COVID-19 Infection: A Cross-Sectional Study in Iran with a Meta-Analytic Review of the Literature. Head Face Med. 2023, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xie, X.; Tian, H.; Wu, T.; Liu, C.; Huang, K.; Gong, R.; Yu, Y.; Luo, T.; Jiao, R.; et al. Mental Fatigue and Negative Emotion among Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 8123–8131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartone, P.T.; McDonald, K.; Hansma, B.J.; Solomon, J. Hardiness Moderates the Effects of COVID-19 Stress on Anxiety and Depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 317, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoemann, A.M.; Boulton, A.J.; Short, S.D. Determining Power and Sample Size for Simple and Complex Mediation Models. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2017, 8, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo-Cuenca, A.I.; Fernández-Fernández, B.; Carmona-Torres, J.M.; Pozuelo-Carrascosa, D.P.; Laredo-Aguilera, J.A.; Romero-Gómez, B.; Rodríguez-Cañamero, S.; Barroso-Corroto, E.; Santacruz-Salas, E. Longitudinal Study of the Mental Health, Resilience, and Post-Traumatic Stress of Senior Nursing Students to Nursing Graduates during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jubin, J.; Delmas, P.; Gilles, I.; Oulevey Bachmann, A.; Ortoleva Bucher, C. Factors Protecting Swiss Nurses’ Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Study. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Campayo, J.; Zamorano, E.; Ruiz, M.A.; Pardo, A.; Pérez-Páramo, M.; López-Gómez, V.; Freire, O.; Rejas, J. Cultural Adaptation into Spanish of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) Scale as a Screening Tool. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbri, M.; Beracci, A.; Martoni, M.; Meneo, D.; Tonetti, L.; Natale, V. Measuring Subjective Sleep Quality: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastien, C.H.; Vallières, A.; Morin, C.M. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an Outcome Measure for Insomnia Research. Sleep Med. 2001, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.; Leiter, M. The maslach burnout inventory manual. In Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources; Zalaquett, C.P., Wood, R.J., Eds.; Scarecrow Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 1997; Volume 3, pp. 191–218. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Monte, P.R. Factorial Validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI-HSS) among Spanish Professionals. Rev. Saude Publica 2005, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillanders, D.T.; Bolderston, H.; Bond, F.W.; Dempster, M.; Flaxman, P.E.; Campbell, L.; Kerr, S.; Tansey, L.; Noel, P.; Ferenbach, C.; et al. The Development and Initial Validation of the Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire. Behav. Ther. 2014, 45, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Moreno, R.; Márquez-González, M.; Losada, A.; Gillanders, D.; Fernández-Fernández, V. Cognitive Fusion in Dementia Caregiving: Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version of the “Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire. Behav. Psychol. 2014, 22, 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez, P.S.; García, A.M.P.; Moreno, J.B. Escala de Autoeficacia General: Datos Psicométricos de La Adaptación Para Población Española. Psicothema 2000, 12, 509–513. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, A.; Garrosa Hernández, E.; Blanco, L.M. Development and Validation of the Occupational Hardiness Questionnaire. Psicothema 2014, 26, 207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Milutinović, D.; Golubović, B.; Brkić, N.; Prokeš, B. Professional Stress and Health among Critical Care Nurses in Serbia. Arh. Hig. Rada Toksikol. 2012, 63, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, J.; Gustavsson, A.; Svensson, M.; Wittchen, H.-U.; Jönsson, B. The Economic Cost of Brain Disorders in Europe. Eur. J. Neurol. 2012, 19, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, B.K.; Jensen, R.; Olesen, J. A Population-Based Analysis of the Diagnostic Criteria of the International Headache Society. Cephalalgia 1991, 11, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raggi, A.; Giovannetti, A.M.; Quintas, R.; D’Amico, D.; Cieza, A.; Sabariego, C.; Bickenbach, J.E.; Leonardi, M. A Systematic Review of the Psychosocial Difficulties Relevant to Patients with Migraine. J. Headache Pain 2012, 13, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, T.J.; Stovner, L.J.; Birbeck, G.L. Migraine: The Seventh Disabler. Cephalalgia 2013, 33, 289–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartley, E.J.; Fillingim, R.B. Sex Differences in Pain: A Brief Review of Clinical and Experimental Findings. Br. J. Anaesth. 2013, 111, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, A.; Santangelo, G.; Tessitore, A.; Silvestro, M.; Trojsi, F.; De Mase, A.; Garramone, F.; Trojano, L.; Tedeschi, G. Coping Strategies in Migraine without Aura: A Cross-Sectional Study. Behav. Neurol. 2019, 2019, 5808610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobos, D.; Szabó, E.; Baksa, D.; Gecse, K.; Kocsel, N.; Pap, D.; Zsombók, T.; Kozák, L.R.; Kökönyei, G.; Juhász, G. Regular Practice of Autogenic Training Reduces Migraine Frequency and Is Associated With Brain Activity Changes in Response to Fearful Visual Stimuli. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 780081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Li, R.; He, M.; Cui, F.; Sun, T.; Xiong, J.; Zhao, D.; Na, W.; Liu, R.; Yu, S. Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Headache amongst Medical Staff in South China. J. Headache Pain 2020, 21, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almalki, D.; Shubair, M.M.; Al-Khateeb, B.F.; Obaid Alshammari, R.A.; Alshahrani, S.M.; Aldahash, R.; Angawi, K.; Alsalamah, M.; Al-Zahrani, J.; Al-Ghamdi, S.; et al. The Prevalence of Headache and Associated Factors in Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pain Res. Manag. 2021, 2021, 6682094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis; Hardcover; Springer Publishing Co: New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 0-8261-1250-1. [Google Scholar]

- Janson, D.J.; Clift, B.C.; Dhokia, V. PPE Fit of Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Appl. Ergon. 2022, 99, 103610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebmann, T.; Vassallo, A.; Holdsworth, J.E. Availability of Personal Protective Equipment and Infection Prevention Supplies during the First Month of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Study by the APIC COVID-19 Task Force. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 434–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hedrera, F.J.; Gil-Almagro, F.; Carmona-Monge, F.J.; Peñacoba-Puente, C.; Catalá-Mesón, P.; Velasco-Furlong, L. Intensive Care Unit Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain: Social and Work-Related Variables, COVID-19 Symptoms, Worries, and Generalized Anxiety Levels. Acute Crit. Care 2021, 36, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, A.; Ducette, J.; Adler, D.C. Stress in ICU and Non-ICU Nurses. Nurs. Res. 1985, 34, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishita, N.; Morimoto, H.; Márquez-González, M.; Barrera-Caballero, S.; Vara-García, C.; Van Hout, E.; Contreras, M.; Losada-Baltar, A. Family Carers of People with Dementia in Japan, Spain, and the UK: A Cross-Cultural Comparison of the Relationships between Experiential Avoidance, Cognitive Fusion, and Carer Depression. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2023, 36, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wu, X.; Gao, Y.; Xiao, C.; Xiao, J.; Fang, F.; Chen, Y. A Longitudinal Study of Perinatal Depression and the Risk Role of Cognitive Fusion and Perceived Stress on Postpartum Depression. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.-Q.; Zhang, R.; Lu, Y.; Liu, H.; Kong, S.; Baker, J.S.; Zhang, H. Occupational Stressors, Mental Health, and Sleep Difficulty among Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Roles of Cognitive Fusion and Cognitive Reappraisal. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2021, 19, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Xie, J.; Owusua, T.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Qin, C.; He, Q. Is Psychological Flexibility a Mediator between Perceived Stress and General Anxiety or Depression among Suspected Patients of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)? Pers. Individ. Dif. 2021, 183, 111132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschleman, K.J.; Bowling, N.A.; Alarcon, G.M. A Meta-Analytic Examination of Hardiness. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2010, 17, 277–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobasa, S.C. Stressful Life Events, Personality, and Health: An Inquiry into Hardiness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1979, 37, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Servellen, G.; Topf, M.; Leake, B. Personality Hardiness, Work-Related Stress, and Health in Hospital Nurses. Hosp. Top. 1994, 72, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahi, A.; Abu Talib, M.; Yaacob, S.N.; Ismail, Z. Hardiness as a Mediator between Perceived Stress and Happiness in Nurses. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 21, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daines, P.A. Personality Hardiness: An Essential Attribute for the ICU Nurse? Dynamics 2000, 11, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hyun, H.S.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, J.H. Factors Associated With Post-Traumatic Growth Among Healthcare Workers Who Experienced the Outbreak of MERS Virus in South Korea: A Mixed-Method Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 541510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epishin, V.E.; Salikhova, A.B.; Bogacheva, N.V.; Bogdanova, M.D.; Kiseleva, M.G. Mental Health and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Hardiness and Meaningfulness Reduce Negative Effects on Psychological Well-Being. Psychol. Russ. State Art 2020, 13, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oral, M.; Karakurt, N. The Impact of Psychological Hardiness on Intolerance of Uncertainty in University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Community Psychol. 2022, 50, 3574–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buselli, R.; Corsi, M.; Veltri, A.; Baldanzi, S.; Chiumiento, M.; Del Lupo, E.; Marino, R.; Necciari, G.; Caldi, F.; Foddis, R.; et al. Mental Health of Health Care Workers (HCWs): A Review of Organizational Interventions Put in Place by Local Institutions to Cope with New Psychosocial Challenges Resulting from COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 299, 113847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottisova, L.; Gillard, J.A.; Wood, M.; Langford, S.; John-Baptiste Bastien, R.; Madinah Haris, A.; Wild, J.; Bloomfield, M.A.P.; Robertson, M. Effectiveness of Psychosocial Interventions in Mitigating Adverse Mental Health Outcomes among Disaster-Exposed Health Care Workers: A Systematic Review. J. Trauma. Stress 2022, 35, 746–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalev-Antsel, T.; Winocur-Arias, O.; Friedman-Rubin, P.; Naim, G.; Keren, L.; Eli, I.; Emodi-Perlman, A. The continuous adverse impact of COVID-19 on temporomandibular disorders and bruxism: Comparison of pre-during-and post-pandemic time periods. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zieliński, G.; Pająk-Zielińska, B.; Ginszt, M. A Meta-Analysis of the Global Prevalence of Temporomandibular Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reus, J.C.; Polmann, H.; Souza, B.D.M.; Flores-Mir, C.; Gonçalves, D.A.G.; de Queiroz, L.P.; Okeson, J.; Canto, G.D.L. Association between primary headaches and temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2022, 153, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Headaches at the First Time Point | Chronic Headaches | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | f (%) | Yes 93 (71%) | No 38 (29%) | Statistical Analysis | Yes 76 (58.8%) | No 54 (41.2%) | Statistical Analysis | |||||

| p Value | χ2/t | Effect Size 2 | p Value | χ2/t | Effect Size 2 | |||||||

| Age | 40.54 (10.02) | 40.52 (9.41) | 40.61 (11.52) | 0.96 | 0.043 | 0.008 | 39.76 (9.47) | 41.67 (10.76) | 0.287 | 1.069 | 0.48 | |

| Work experience | 11.76 (9.34) | 11.45 (9.11) | 12.50 (9.10) | 0.56 | 0.581 | 0.11 | 11.18 (9.15) | 12.57 (9.64) | 0.404 | 0.838 | 0.14 | |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | 15 (11.5) | 7 (46.78%) | 8 (53.3%) | 0.03 | 4.868 | 3.27 [1.09,9.80] | 7 (46.7%) | 8 (53.3%) | 0.311 | 1.026 | 1.73 [0.59,5.12] | |

| Female | 116 (88.5) | 86 (74.1%) | 30 (22.9%) | 70 (60.3%) | 46 (39.7%) | |||||||

| Family Status | ||||||||||||

| Married/cohabiting | 88 (67.2) | 61 (69.3%) | 27 (30.7%) | 0.62 | 0.365 | 0.77 [0.34,1.76] | 51 (58%) | 37 (42%) | 0.784 | 0.075 | 0.90 [0.42,1.89] | |

| Single | 43 (32.8) | 32 (74.4%) | 11 (25.9%) | 26 (60.5%) | 17 (39.5%) | |||||||

| Employment S 1 | ||||||||||||

| Permanent | 78 (59.5) | 51 (65.4%) | 27 (20.6%) | 0.11 | 2.944 | 2.02 [0.89,4.55] | 42 (53.8%) | 36 (46.2%) | 0.164 | 1.936 | 1.66 [0.81,3.43] | |

| Not permanent | 53 (40.5) | 42 (79.2%) | 11 (28.8%) | 35 (66%) | 18 (34.0%) | |||||||

| Transfer to ICU | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 29 (22.1) | 23 (79.3%) | 6 (20.7%) | 0.26 | 1.251 | 1.75 [0.65,4.72] | 17 (58.6%) | 12 (41.4%) | 0.984 | 0.001 | 0.99 [0.42,2.29] | |

| No | 102 (77.9) | 70 (68.6%) | 32 (31.4%) | 60 (58.8%) | 42 (41.2%) | |||||||

| PCR+ | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 54 (41.2) | 38 (70.4%) | 16 (29.6%) | 0.89 | 0.017 | 1.05 [0.49,2.26] | 32 (59.3%) | 22 (40.7%) | 0.925 | 0.009 | 0.96 [0.47,1.96] | |

| No | 77 (58.8) | 55 (71.4%) | 22 (28.6%) | 45 (58.4%) | 32 (41.6%) | |||||||

| Availability of PPE | ||||||||||||

| Yes or usually | 68 (51.9) | 45 (66.2%) | 23 (33.8%) | 0.20 | 1.592 | 0.61 [0.28,1.31] | 38 (55.9%) | 30 (44.1%) | 0.484 | 0.490 | 0.77 [0.38,1.56] | |

| No or rarely | 63 (48.1) | 48 (76.2%) | 15 (23.8%) | 39 (61.9%) | 24 (38.1%) | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | Chronic Headaches | Statistical Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | p Value | t Student | Cohen’s d | ||

| Anxiety | 8.64 (4.84) | 9.64 (4.61) | 7.22 (4.85) | 0.005 | −2.414 | 0.51 |

| Insomnia | 10.34 (6.01) | 11.29 (6.14) | 8.98 (5.60) | 0.030 | −2.304 | 0.39 |

| Emotional Fatigue | 26.98 (12.57) | 29.08 (12.43) | 23.98 (12.27) | 0.022 | −5.096 | 0.41 |

| Depersonalization | 6.30 (5.60) | 6.86 (5.58) | 5.50 (5.58) | 0.173 | −1.357 | 0.24 |

| Reduced Personal Acc 1 | 13.16 (7.17) | 14.16 (8.93) | 11.77 (7.83) | 0.117 | −2.378 | 0.27 |

| Cognitive Fusion | 22.24 (10.29) | 23.71 (10.20) | 20.15 (23.71) | 0.049 | −3.566 | 0.19 |

| Hardiness | 66.53 (9.60) | 66.01 (9.23) | 68.69 (9.79) | 0.031 | 3.672 | 0.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gil-Almagro, F.; Carmona-Monge, F.J.; García-Hedrera, F.J.; Peñacoba-Puente, C. Headache and Associated Psychological Variables in Intensive Care Unit Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Prospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3767. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133767

Gil-Almagro F, Carmona-Monge FJ, García-Hedrera FJ, Peñacoba-Puente C. Headache and Associated Psychological Variables in Intensive Care Unit Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Prospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(13):3767. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133767

Chicago/Turabian StyleGil-Almagro, Fernanda, Francisco Javier Carmona-Monge, Fernando José García-Hedrera, and Cecilia Peñacoba-Puente. 2024. "Headache and Associated Psychological Variables in Intensive Care Unit Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Prospective Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 13: 3767. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133767

APA StyleGil-Almagro, F., Carmona-Monge, F. J., García-Hedrera, F. J., & Peñacoba-Puente, C. (2024). Headache and Associated Psychological Variables in Intensive Care Unit Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Prospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(13), 3767. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133767