The Impact of COVID-19 Lockdowns in Germany on Mood, Attention Control, Immune Fitness, and Quality of Life of Young Adults with Self-Reported Impaired Wound Healing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Attention Control

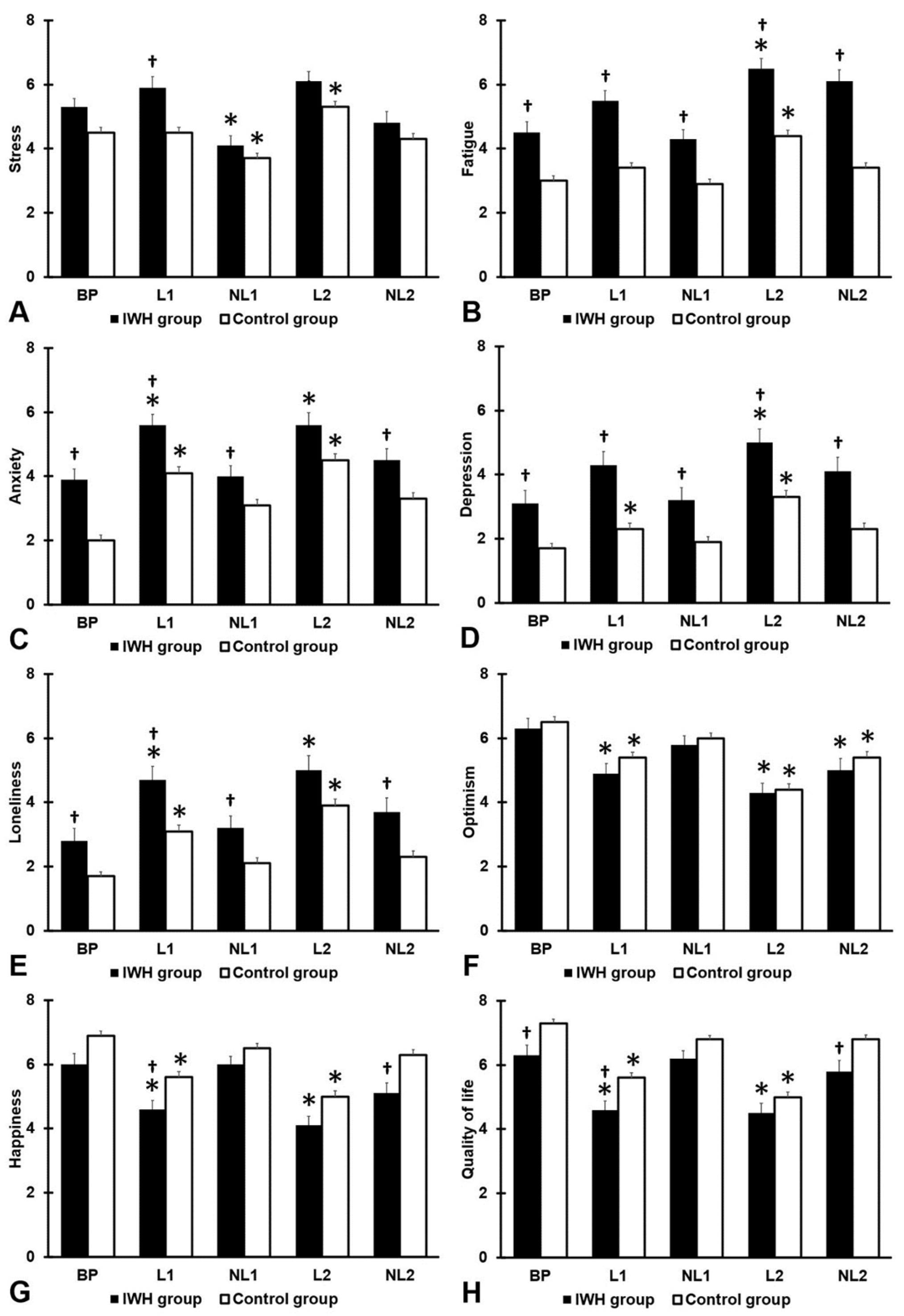

3.2. Mood

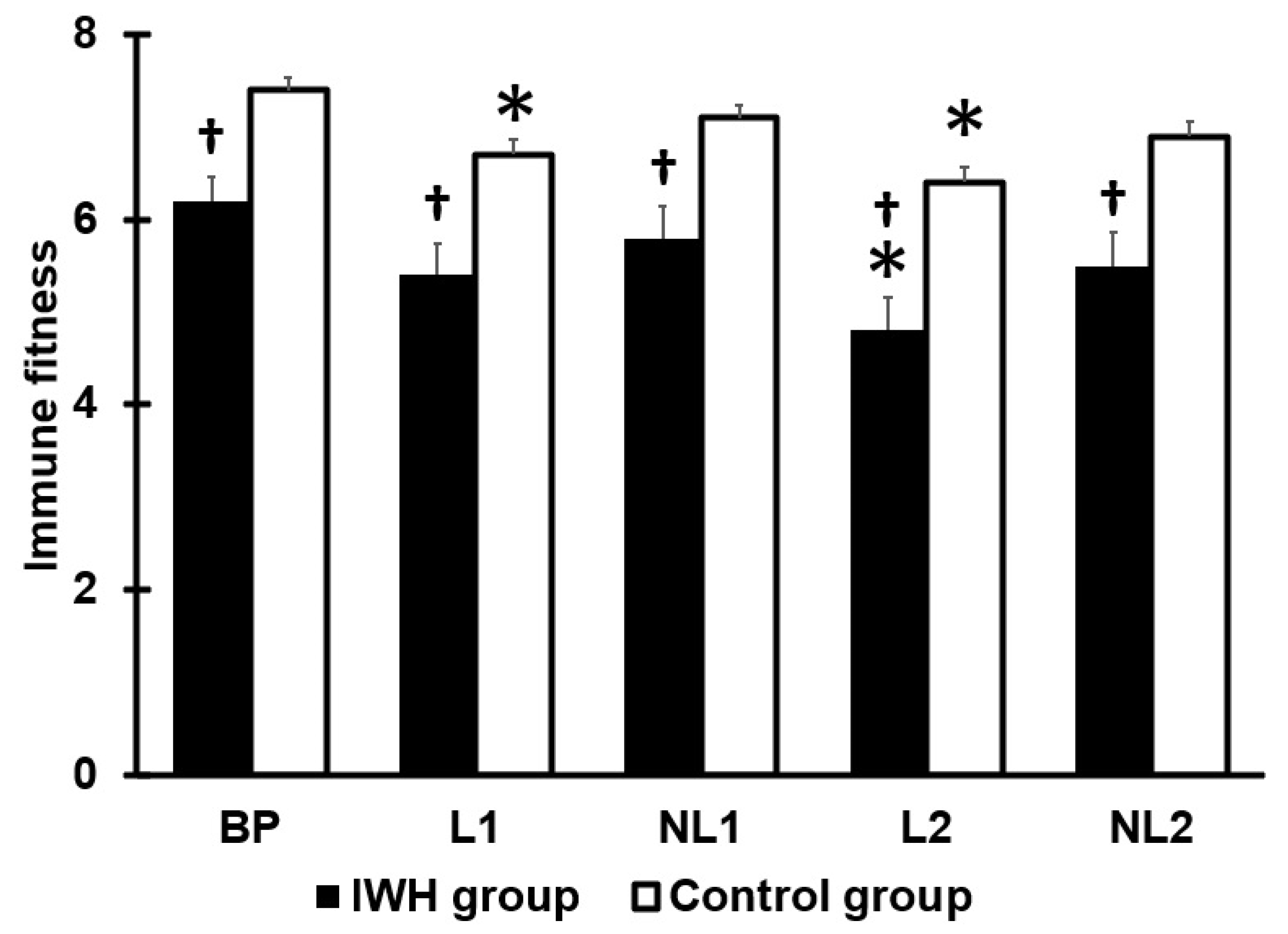

3.3. Immune Fitness

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Emanuel, E.J.; Persad, G.; Upshur, R.; Thome, B.; Parker, M.; Glickman, A.; Zhang, C.; Boyle, C.; Smith, M.; Phillips, J.P. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2049–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laux, C.J.; Bauer, D.E.; Kohler, A.; Uçkay, I.; Farshad, M. Disproportionate case reduction after banning of elective surgeries during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Clin. Spine Surg. 2020, 33, 244–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Mancini, A.D. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: A review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilan, D.; Röthke, N.; Blessin, M.; Kunzler, A.; Stoffers-Winterling, J.; Müssig, M.; Yuen, K.; Thrul, J.; Kreuter, F.; Lieb, K.; et al. Psychomorbidity, resilience, and exacerbating and protective factors during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2020, 117, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriksen, P.A.; Kiani, P.; Garssen, J.; Bruce, G.; Verster, J.C. Living alone or together during a lockdown: Association with mood, immune fitness and experiencing COVID-19 symptoms. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 1947–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriksen, P.A.; Garssen, J.; Bijlsma, E.Y.; Engels, F.; Bruce, G.; Verster, J.C. COVID-19 lockdown-related changes in mood, health and academic functioning. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 1440–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sud, A.; Jones, M.E.; Broggio, J.; Loveday, C.; Torr, B.; Garrett, A.; Nicol, D.L.; Jhanji, S.; Boyce, S.A.; Turnbull, C.; et al. Collateral damage: The impact on outcomes from cancer surgery of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Physical, E.; Alliance, R.M.B. White book on physical and rehabilitation medicine in Europe. Chapter 2. Why rehabilitation is needed by individuals and society. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 54, 166–176. [Google Scholar]

- Koyun, A.H.; Hendriksen, P.A.; Kiani, P.; Merlo, A.; Balikji, J.; Stock, A.-K.; Verster, J.C. COVID-19 lockdown effects on mood, alcohol consumption, academic functioning, and perceived immune fitness: Data from young adults in Germany. Data 2022, 7, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinelli, G.; Sica, S.; Guarnera, G.; Pitocco, D.; Tshomba, Y. Wound care during COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 68, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balikji, J.; Kiani, P.; Hendriksen, P.A.; Hoogbergen, M.M.; Garssen, J.; Verster, J.C. Impaired wound healing is associated with poorer mood and reduced perceived immune fitness during the COVID-19 pandemic: A retrospective survey. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlager, J.G.; Kendziora, B.; Patzak, L.; Kupf, S.; Rothenberger, C.; Fiocco, Z.; French, L.E.; Reinholz, M.; Hartmann, D. Impact of COVID-19 on wound care in Germany. Int. Wound J. 2021, 18, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollmann, A.; Hohenstein, S.; Meier-Hellmann, A.; Kuhlen, R.; Hindricks, G. Emergency hospital admissions and interventional treatments for heart failure and cardiac arrhythmias in Germany during the COVID-19 outbreak: Insights from the German-wide Helios hospital network. Eur. Heart J. Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes 2020, 6, 221–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollmann, A.; Pellissier, V.; Hohenstein, S.; König, S.; Ueberham, L.; Meier-Hellmann, A.; Kuhlen, R.; Thiele, H.; Hindricks, G. Helios hospitals, Germany. Cumulative hospitalization deficit for cardiovascular disorders in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic: Insights from the German-wide Helios hospital network. Eur. Heart J. Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes 2021, 7, e5–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollmann, A.; Hohenstein, S.; Pellissier, V.; Stengler, K.; Reichardt, P.; Ritz, J.P.; Thiele, H.; Borger, M.A.; Hindricks, G.; Meier-Hellmann, A.; et al. Utilization of in- and outpatient hospital care in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic insights from the German-wide Helios hospital network. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, S.; Hohenstein, S.; Ueberham, L.; Hindricks, G.; Meier-Hellmann, A.; Kuhlen, R.; Bollmann, A. Regional and temporal disparities of excess all-cause mortality for Germany in 2020: Is there more than just COVID-19? J. Infect. 2021, 82, 186–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balikji, J.; Hoogbergen, M.M.; Garssen, J.; Verster, J.C. Mental resilience, mood, and quality of life in young adults with self-reported impaired wound healing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balikji, J.; Garssen, J.; Hoogbergen, M.M.; Roth, T.; Verster, J.C. Insomnia complaints and perceived immune fitness in students with and without self-reported impaired wound healing. Medicina 2022, 58, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balikji, J.; Hoogbergen, M.M.; Garssen, J.; Verster, J.C. Inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity pose individuals with impaired wound healing at increased risk for accidents and injury. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balikji, J.; Hoogbergen, M.M.; Garssen, J.; Verster, J.C. Self-reported impaired wound healing in young adults and their susceptibility to experiencing immune-related complaints. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derryberry, D.; Reed, M.A. Anxiety-related attentional biases and their regulation by attentional control. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2002, 111, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verster, J.C.; Sandalova, E.; Garssen, J.; Bruce, G. The use of single-item ratings versus traditional multiple-item questionnaires to assess mood and health. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verster, J.C.; Mulder, K.E.W.; Hendriksen, P.A.; Verheul, M.C.E.; van Oostrom, E.C.; Scholey, A.; Garssen, J. Test-retest reliability of single-item assessments of immune fitness, mood and quality of life. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boer, A.G.; van Lanschot, J.J.; Stalmeier, P.F.; van Sandick, J.W.; Hulscher, J.B.; de Haes, J.C.; Sprangers, M.A. Is a single-item visual analogue scale as valid, reliable and responsive as multi-item scales in measuring quality of life? Qual. Life Res. 2004, 13, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schrojenstein Lantman, M.; Mackus, M.; Otten, L.S.; de Kruijff, D.; van de Loo, A.J.; Kraneveld, A.D.; Garssen, J.; Verster, J.C. Mental resilience, perceived immune functioning, and health. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2017, 10, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verster, J.C.; Kraneveld, A.D.; Garssen, J. The assessment of immune fitness. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiani, P.; Balikji, J.; Kraneveld, A.D.; Garssen, J.; Bruce, G.; Verster, J.C. Pandemic preparedness: The importance of adequate immune fitness. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebach, C.L.; Kirkhart, M.; Lating, J.M.; Wegener, S.T.; Song, Y.; Riley, L.H., 3rd; Archer, K.R. Examining the role of positive and negative affect in recovery from spine surgery. Pain 2012, 153, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, F.R.; Aitken, L.M.; Tower, M. An integrative review of self-efficacy and patient recovery post-acute injury. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 714–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Sinha, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Poddar, S. Studies on the awareness, apprehensions and aspirations of the university students of West Bengal, India in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. Malay. J. Med. Res. 2021, 5, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadayian, A.; Merlo, A.; Czerniczyniec, A.; Lores-Arnaiz, S.; Hendriksen, P.A.; Kiani, P.; Bruce, G.; Verster, J.C. Alcohol consumption, hangovers, and smoking among Buenos Aires university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lolo, W.A.; Citraningtyas, G.; Mpila, D.A.; Wijaya, H.; Poddar, S. Quality of life of hypertensive patients undergoing chronic disease management program during the COVID-19 pandemic. Kesmas J. Kesehat. Masy. Nas. (Natl. Public Health J.) 2022, 17, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control Group | IWH Group | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 251 | 66 | |

| Sex (m/f) (%) | 35.5%/64.5% | 21.2%/78.8% | 0.028 * |

| Age | 25.7 (4.1) | 24.8 (3.9) | 0.134 |

| Immune fitness | 6.9 (2.2) | 5.5 (2.6) | <0.001 * |

| Reduced immune fitness (%) | 24.90% | 56.6% | <0.001 * |

| Sleep quality | 6.7 (2.3) | 6.1 (2.3) | 0.105 |

| Quality of life | 6.8 (2.0) | 5.8 (2.4) | 0.005 * |

| Control Group | IWH Group | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATTC total score | 51.2 (7.6) | 49.4 (7.9) | 0.151 |

| ATTC—Attention focusing | 22.6 (4.3) | 20.7 (4.2) | 0.007 * |

| ATTC—Attention shifting | 28.7 (4.7) | 28.6 (4.9) | 0.906 |

| Mean (SD) | Overall | Pairwise Comparisons (p-Values) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | Group | BP | L1 | NL1 | L2 | NL2 | p-Value | BP vs. L1 | BP vs. NL1 | BP vs. L2 | BP vs. NL2 |

| Stress | IWH | 5.3 (2.0) | 5.9 (2.6) | 4.1 (2.3) | 6.1 (2.3) | 4.8 (2.6) | <0.001 * | 0.120 | 0.004 * | 0.042 | 0.256 |

| Control | 4.5 (2.5) | 4.5 (2.6) | 3.7 (2.4) | 5.3 (2.6) | 4.3 (2.6) | <0.001 * | 0.824 | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | 0.382 | |

| p-value | 0.024 | <0.001 † | 0.295 | 0.060 | 0.172 | ||||||

| Fatigue | IWH | 4.5 (2.6) | 5.5 (2.3) | 4.3 (2.3) | 6.5 (2.4) | 5.1 (2.7) | <0.001 * | 0.031 | 0.244 | <0.001 * | 0.039 |

| Control | 3.0 (2.4) | 3.4 (2.5) | 2.9 (2.3) | 4.4 (2.7) | 3.4 (2.5) | <0.001 * | 0.027 | 0.439 | <0.001 * | 0.012 | |

| p-value | <0.001 † | <0.001 † | <0.001 † | <0.001 † | <0.001 † | ||||||

| Anxiety | IWH | 3.9 (2.5) | 5.6 (2.6) | 4.0 (2.5) | 5.6 (2.9) | 4.5 (2.7) | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | 0.881 | <0.001 * | 0.310 |

| Control | 3.0 (2.6) | 4.1 (2.9) | 3.1 (2.6) | 4.5 (3.0) | 3.3 (2.7) | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | 0.496 | <0.001 * | 0.173 | |

| p-value | 0.008 † | <0.001 † | 0.008 † | 0.016 | 0.001 † | ||||||

| Depression | IWH | 3.1 (3.1) | 4.3 (3.2) | 3.2 (3.0) | 5.0 (3.1) | 4.1 (3.4) | <0.001 * | 0.012 | 0.788 | <0.001 * | 0.049 |

| Control | 1.7 (2.3) | 2.3 (2.7) | 1.9 (2.4) | 3.3 (3.1) | 2.3 (2.7) | <0.001 * | 0.005 * | 0.466 | <0.001 * | 0.013 | |

| p-value | <0.001 † | <0.001 † | 0.002 † | <0.001 † | <0.001 † | ||||||

| Loneliness | IWH | 2.8 (2.8) | 4.7 (3.1) | 3.2 (2.7) | 5.0 (3.4) | 3.7 (3.3) | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | 0.591 | <0.001 * | 0.073 |

| Control | 1.7 (2.1) | 3.1 (3.0) | 2.1 (2.5) | 3.9 (3.2) | 2.3 (2.6) | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | 0.388 | <0.001 * | 0.059 | |

| p-value | 0.008 † | <0.001 † | 0.003 † | 0.023 | 0.005 † | ||||||

| Optimism | IWH | 6.3 (2.3) | 4.9 (2.3) | 5.8 (2.0) | 4.3 (2.2) | 5.0 (2.7) | <0.001 * | 0.007 * | 0.370 | <0.001 * | 0.002 * |

| Control | 6.5 (2.5) | 5.4 (2.4) | 6.0 (2.3) | 4.4 (2.6) | 5.4 (2.7) | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | 0.030 | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | |

| p-value | 0.422 | 0.166 | 0.291 | 0.736 | 0.441 | ||||||

| Happiness | IWH | 6.0 (2.4) | 4.6 (2.1) | 6.0 (1.9) | 4.1 (2.2) | 5.1 (2.5) | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | 0.952 | <0.001 * | 0.013 |

| Control | 6.9 (2.2) | 5.6 (2.5) | 6.5 (2.2) | 5.0 (2.5) | 6.3 (2.4) | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | 0.039 | <0.001 * | 0.037 | |

| p-value | 0.017 | 0.004 † | 0.054 | 0.017 | 0.001 † | ||||||

| Quality of life | IWH | 6.3 (2.3) | 4.6 (1.9) | 6.2 (1.8) | 4.5 (2.2) | 5.8 (2.4) | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | 0.806 | <0.001 * | 0.311 |

| Control | 7.3 (1.9) | 5.6 (2.4) | 6.8 (1.8) | 5.0 (2.4) | 6.8 (2.0) | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | 0.167 | <0.001 * | 0.145 | |

| p-value | 0.002 † | 0.006 † | 0.026 | 0.341 | 0.005 † | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balikji, J.; Koyun, A.H.; Hendriksen, P.A.; Kiani, P.; Stock, A.-K.; Garssen, J.; Hoogbergen, M.M.; Verster, J.C. The Impact of COVID-19 Lockdowns in Germany on Mood, Attention Control, Immune Fitness, and Quality of Life of Young Adults with Self-Reported Impaired Wound Healing. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3205. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093205

Balikji J, Koyun AH, Hendriksen PA, Kiani P, Stock A-K, Garssen J, Hoogbergen MM, Verster JC. The Impact of COVID-19 Lockdowns in Germany on Mood, Attention Control, Immune Fitness, and Quality of Life of Young Adults with Self-Reported Impaired Wound Healing. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(9):3205. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093205

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalikji, Jessica, Anna H. Koyun, Pauline A. Hendriksen, Pantea Kiani, Ann-Kathrin Stock, Johan Garssen, Maarten M. Hoogbergen, and Joris C. Verster. 2023. "The Impact of COVID-19 Lockdowns in Germany on Mood, Attention Control, Immune Fitness, and Quality of Life of Young Adults with Self-Reported Impaired Wound Healing" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 9: 3205. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093205

APA StyleBalikji, J., Koyun, A. H., Hendriksen, P. A., Kiani, P., Stock, A.-K., Garssen, J., Hoogbergen, M. M., & Verster, J. C. (2023). The Impact of COVID-19 Lockdowns in Germany on Mood, Attention Control, Immune Fitness, and Quality of Life of Young Adults with Self-Reported Impaired Wound Healing. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(9), 3205. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093205