Emergency Colectomies in the Elderly Population—Perioperative Mortality Risk-Factors and Long-Term Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Rationale, Variables, and Outcome Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Institute on Aging (NIA). Why Population Aging Matters: A Global Perspective. Report by the National Institute on Aging, Summit on Global Aging. 2007. Available online: http://www.nia.nih.gov/ResearchInformation/ExtramuralPrograms/BehavioralAndSocialResearch/GlobalAging.htm (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Rix, T.E.; Bates, T. Pre-operative risk scores for the prediction of outcome in elderly people who require emergency surgery. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2007, 2, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biondi, A.; Vacante, M.; Ambrosino, I.; Cristaldi, E.; Pietrapertosa, G.; Basile, F. Role of surgery for colorectal cancer in the elderly. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2016, 8, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etzioni, D.A.; Liu, J.H.; Maggard, M.A.; Ko, C.Y. The Aging Population and Its Impact on the Surgery Workforce. Ann. Surg. 2003, 238, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.; Naishadham, D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2013, 63, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hupfeld, L.; Pommergaard, H.-C.; Burcharth, J.; Rosenberg, J. Emergency admissions for complicated colonic diverticulitis are increasing: A nationwide register-based cohort study. Int. J. Colorectal. Dis. 2018, 33, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, L.J.; Feuerstadt, P.; Longstreth, G.F.; Boley, S.J. American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: Epidemiology, risk factors, patterns of presentation, diagnosis, and management of colon ischemia (CI). Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, C.S.; Hole, D.J. Emergency presentation of colorectal cancer is associated with poor 5-year survival. Br. J. Surg. 2004, 91, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basili, G.; Lorenzetti, L.; Biondi, G.; Preziuso, E.; Angrisano, C.; Carnesecchi, P.; Roberto, E.; Goletti, O. Colorectal cancer in the elderly. Is there a role for safe and curative surgery? ANZ J. Surg. 2008, 78, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagard, K.; Casaer, J.; Wolthuis, A.; Flamaing, J.; Milisen, K.; Lobelle, J.P.; Wildiers, H.; Kenis, C. Postoperative complications in individuals aged 70 and over undergoing elective surgery for colorectal cancer. Color. Dis. 2017, 19, O329–O338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGillicuddy, E.A.; Schuster, K.M.; Davis, K.A.; Longo, W.E. Factors predicting morbidity and mortality in emergency colorectal procedures in elderly patients. Arch Surg. 2009, 144, 1157–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modini, C.; Romagnoli, F.; De Milito, R.; Romeo, V.; Petroni, R.; La Torre, F.; Catani, M. Octogenarians: An increasing challenge for acute care and colorectal surgeons. An outcomes analysis of emergency colorectal surgery in the elderly. Colorectal. Dis. 2012, 14, e312–e318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klima, D.A.; Brintzenhoff, R.A.; Agee, N.; Walters, A.; Heniford, B.T.; Mostafa, G. A Review of Factors that Affect Mortality Following Colectomy. J. Surg. Res. 2012, 174, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-S.; Watts, J.N.; Peel, N.M.; Hubbard, R.E. Frailty and post-operative outcomes in older surgical patients: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassahun, W.T. The effects of pre-existing dementia on surgical outcomes in emergent and nonemergent general surgical procedures: Assessing differences in surgical risk with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehaffey, J.H.; Hawkins, R.; Tracci, M.C.; Robinson, W.P.; Cherry, K.J.; Kern, J.A.; Upchurch, G.R. Preoperative dementia is associated with increased cost and complications after vascular surgery. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 68, 1203–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Zhang, P.; Liang, X.; Wu, Z.; Wang, J.; Liang, Y. Association between dementia and mortality in the elderly patients undergoing hip fracture surgery: A meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2018, 13, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, B.C.; Brungardt, J.; Reyes, J.; Helmer, S.D.; Haan, J.M. Dementia as a predictor of mortality in adult trauma patients. Am. J. Surg. 2018, 215, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.; Hayden, J.; Springer, J.; Bailey, J.; Molinari, M.; Johnson, P. Prognostic factors for morbidity and mortality in elderly patients undergoing acute gastrointestinal surgery: A systematic review. Can J. Surg. 2014, 57, E44–E52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenal, J.J.; Bengoechea-Beeby, M. Mortality associated with emergency abdominal surgery in the elderly. Can. J. Surg. 2003, 46, 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- McIsaac, D.I.; Taljaard, M.; Bryson, G.L.; Beaulé, P.E.; Gagné, S.; Hamilton, G.; Hladkowicz, E.; Huang, A.; Joanisse, J.A.; Lavallée, L.T.; et al. Frailty as a Predictor of Death or New Disability After Surgery: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann. Surg. 2020, 271, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Attwood, K.; Arya, S.; Hall, D.E.; Johanning, J.M.; Gabriel, E.; Visioni, A.; Nurkin, S.; Kukar, M.; Hochwald, S.; et al. Association of Frailty with Failure to Rescue After Low-Risk and High-Risk Inpatient Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2018, 153, e180214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, L.J.; Moore, F.A.; Jones, S.L.; Xu, J.; Bass, B.L. Sepsis in general surgery: A deadly complication. Am. J. Surg. 2009, 198, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mačiulienė, A.; Maleckas, A.; Kriščiukaitis, A.; Mačiulis, V.; Vencius, J.; Macas, A. Predictors of 30-Day In-Hospital Mortality in Patients Undergoing Urgent Abdominal Surgery Due to Acute Peritonitis Complicated with Sepsis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 6331–6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, A.; Evans, L.E.; Alhazzani, W.; Levy, M.M.; Antonelli, M.; Ferrer, R.; Kumar, A.; Sevransky, J.E.; Sprung, C.L.; Nunnally, M.E.; et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017, 43, 304–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulaylat, A.S.; Pappou, E.; Philp, M.M.; Kuritzkes, B.A.; Ortenzi, G.; Hollenbeak, C.S.; Choi, C.; Messaris, E. Emergent Colon Resections. Dis. Colon. Rectum. 2019, 62, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Procedure | Total Cohort n = 613 |

|---|---|

| Right colectomy, n (%) | 178 (29) |

| Hartmann’s procedure, n (%) | 178 (29) |

| Left colectomy, n (%) | 71 (11.5) |

| Sub-total colectomy, n (%) | 54 (9) |

| Cecectomy, n (%) | 53 (8) |

| Sigmoidectomy, n (%) | 29 (4.7) |

| Subtotal colectomy with ileostomy, n (%) | 25 (4) |

| Total colectomy, n (%) | 15 (2.4) |

| Anterior resection, n (%) | 9 (1.4) |

| Abdominoperineal resection, n (%) | 1 (0.1) |

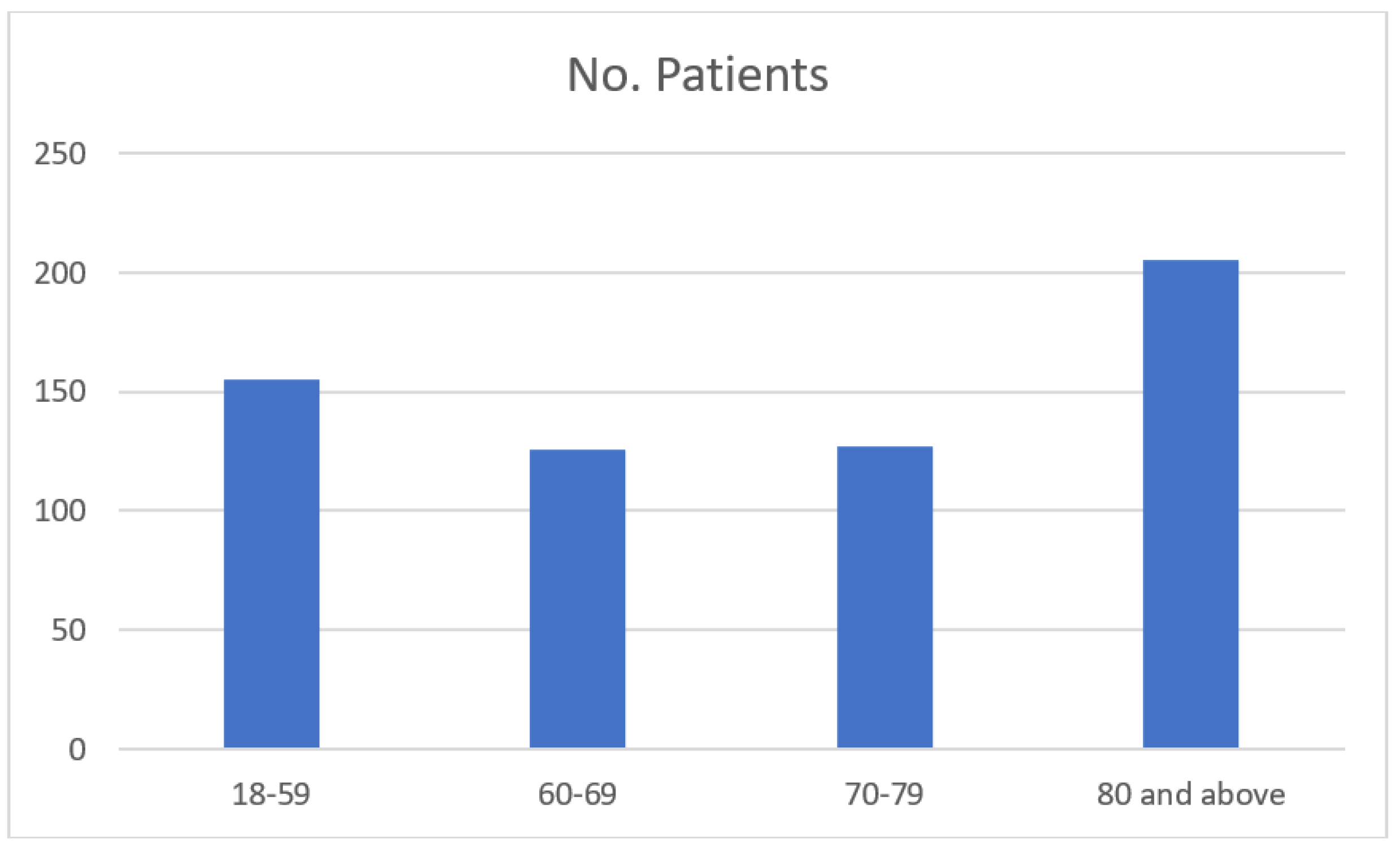

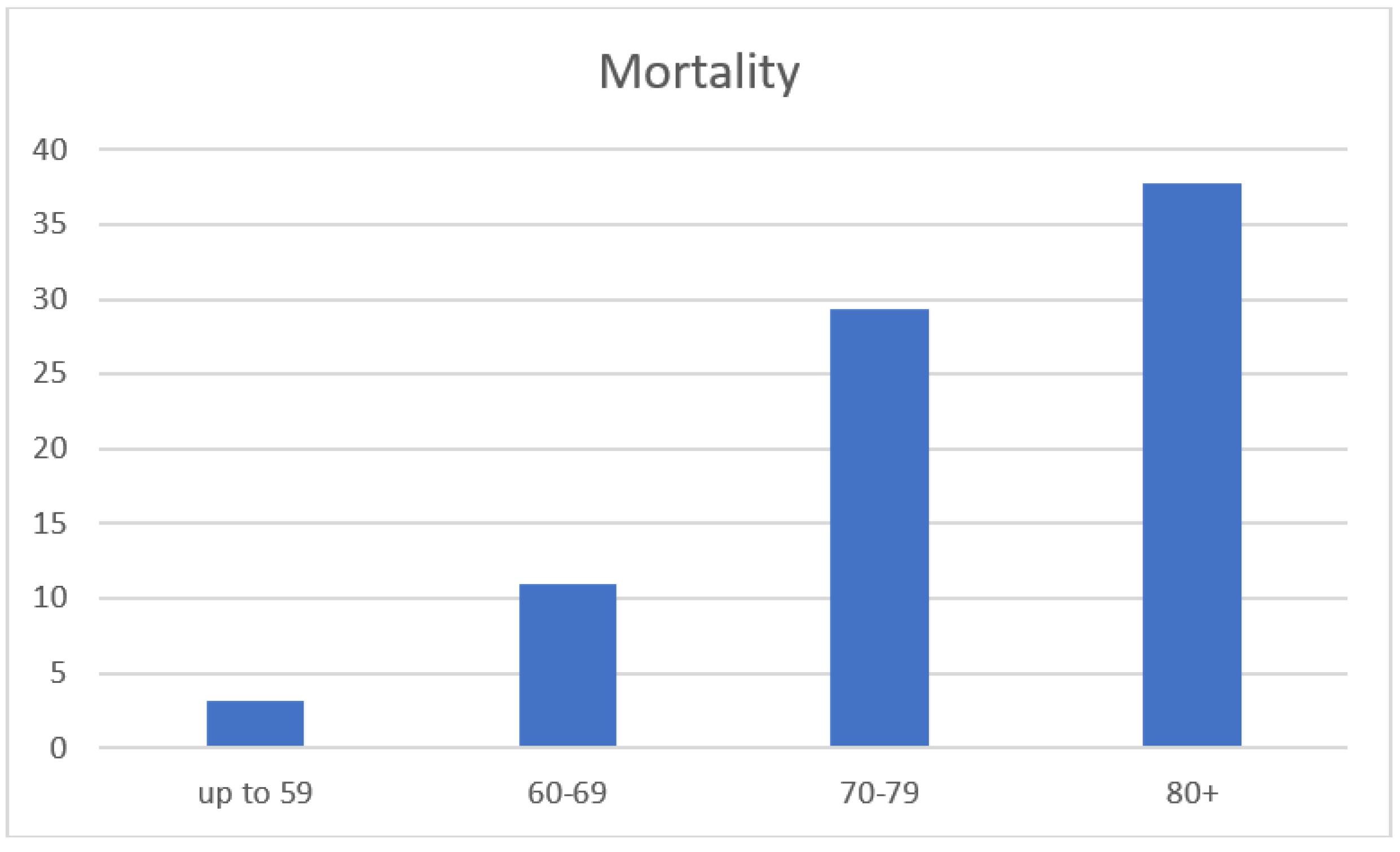

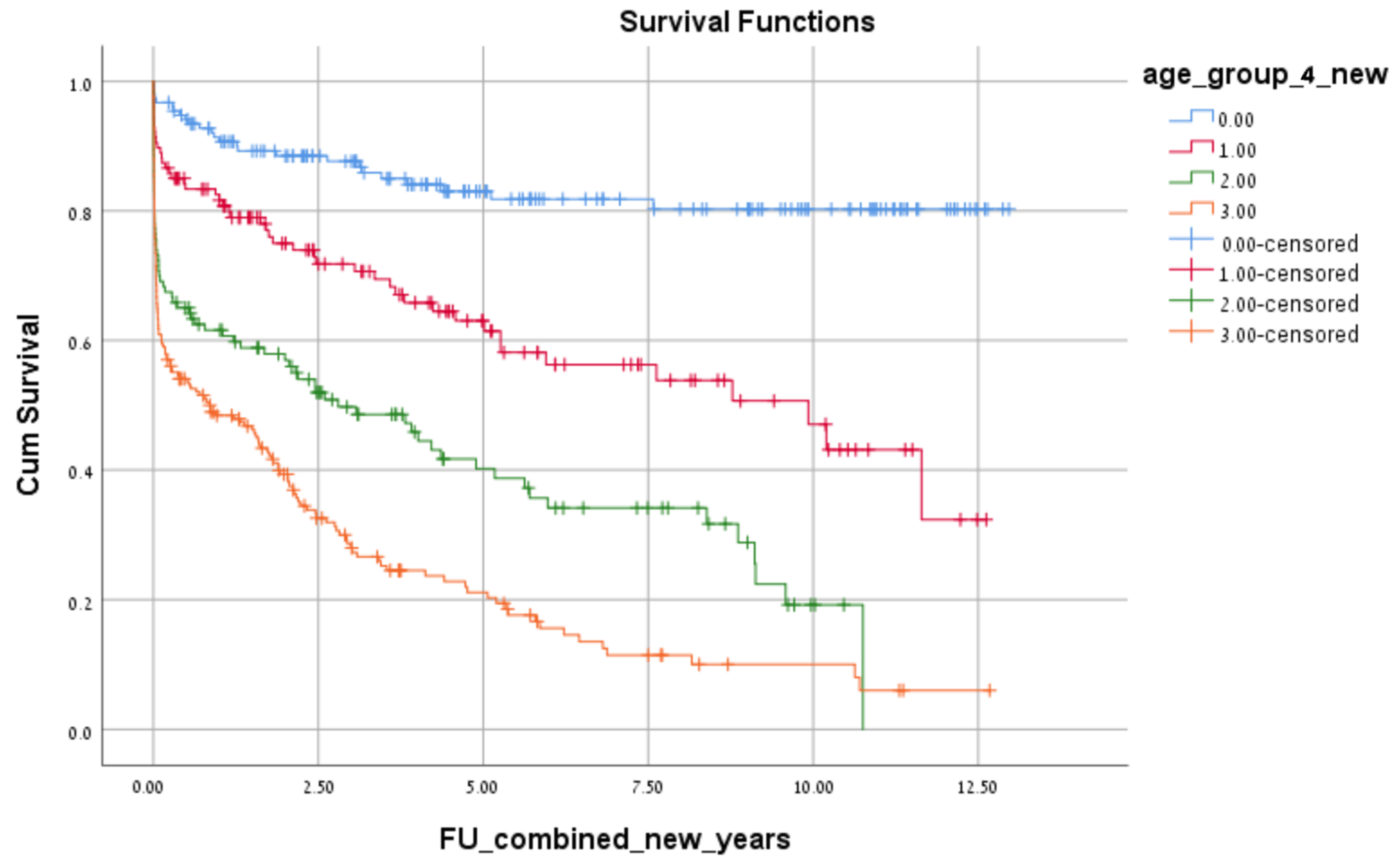

| 18–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survive n= 150 (96.8%) | 30d Death n= 5 (3.2%) | p Value | Survive n= 113 (89%) | 30d Death n= 14 (11%) | p Value | Survive n= 87 (70.7%) | 30d Death n= 36 (29.3%) | p Value | Survive n= 130 (62.2%) | 30d Death n= 79 (37.8%) | p Value | |

| Gender n (%) | 1.000 | 0.392 | 0.877 | 0.107 | ||||||||

| Male | 98 (65.3) | 3 (60) | 71 (62.8) | 7 (50) | 47 (54.0) | 20 (55.6) | 51 (39.2) | 40 (50.6) | ||||

| Female | 52 (34.7) | 2 (40) | 42 (37.2) | 7 (50) | 40 (46.0) | 16 (44.4) | 79 (60.8) | 39 (49.4) | ||||

| BMI mean ± SD | -- | -- | 28.62 ± 5.36 | 31.72 ± 6.98 | 0.162 | 27.23 ± 4.17 | 27.92 ± 7.53 | 0.766 | 25.49 ± 4.55 | 26.23 ± 6.32 | 0.787 | |

| ADL-dependent n (%) | 10 (6.7) | 1 (20) | 0.311 | 12 (10.6) | 8 (57.1) | 0.000 | 7 (8.0) | 12 (33.3) | 0.000 | 30 (23.1) | 37 (47.4) | 0.000 |

| Dementia n (%) | 3 (2) | 1 (20) | 0.124 | 4 (3.5) | 2 (14.3) | 0.131 | 3 (3.4) | 8 (22.2) | 0.002 | 21 (16.2) | 29 (37.2) | 0.001 |

| Cancer n (%) | 121 (80.7) | 4 (80) | 1.000 | 73 (64.6) | 12 (85.7) | 0.141 | 58 (66.7) | 24 (66.7) | 1.000 | 63 (48.5) | 53 (67.1) | 0.009 |

| ASA score n (%) | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.032 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| 1 | 68 (45.3) | 1 (20) | 19 (16.8) | 0 (0) | 6 (6.9) | 2 (5.6) | 8 (6.2) | 5 (6.3) | ||||

| 2 | 54 (36.0) | 2 (40) | 53 (46.9) | 5 (35.7) | 39 (44.8) | 10 (27.8) | 54 (41.5) | 13 (16.5) | ||||

| 3 | 21 (14) | 0 (0) | 36 (31.9) | 4 (28.6) | 36 (41.4) | 15 (41.7) | 64 (49.2) | 50 (63.3) | ||||

| 4 | 7 (4.7) | 2 (40) | 5 (4.4) | 5 (35.7) | 6 (6.9) | 9 (25.0) | 4 (3.1) | 10 (12.7) | ||||

| 5 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 1 (1.3) | ||||

| Charlson score mean ± SD | 1.26 ± 2.52 | 2.60 ± 3.209 | 0.182 | 2.16 ± 2.52 | 2.64 ± 2.24 | 0.173 | 2.77 ± 2.69 | 2.97 ± 2.75 | 0.650 | 3.10 ± 3.23 | 3.33 ± 2.79 | 0.128 |

| LOS mean ± SD | 13.81 ± 12.54 | 7.00 ± 5.38 | 0.087 | 17.23 ± 16.34 | 11.43 ± 8.76 | 0.195 | 14.86 ± 12.30 | 7.25 ± 8.54 | 0.001 | 18.01 ± 16.43 | 9.41 ± 8.68 | 0.000 |

| Blood transfusion n (%) | 16 (10.7) | 2 (40) | 0.103 | 16 (14.2) | 4 (28.6) | 0.234 | 12 (13.8) | 8 (22.2) | 0.249 | 25 (19.2) | 16 (20.3) | 0.857 |

| Hemoglobin mean ± SD | 13.08 ± 2.21 | 12.54 ± 2.87 | 0.594 | 13.05 ± 2.16 | 12.01 ± 1.98 | 0.101 | 12.21 ± 2.05 | 12.10 ± 2.54 | 0.818 | 11.81 ± 1.89 | 13.38 ± 12.43 | 0.385 |

| WBC mean ± SD | 13.09 ± 5.46 | 19.15 ± 6.50 | 0.017 | 12.32 ± 5.25 | 17.68 ± 16.65 | 0.270 | 12.75 ± 4.57 | 14.54 ± 8.04 | 0.247 | 12.13 ± 5.27 | 14.83 ± 8.33 | 0.035 |

| Creatinine mean ± SD | 1.19 ± 1.43 | 2.75 ± 3.50 | 0.441 | 1.21 ± 0.91 | 1.9 ± 1.71 | 0.217 | 1.306 ± 0.927 | 1.946 ± 1.56 | 0.058 | 1.25 ± 0.52 | 1.83 ± 1.60 | 0.000 |

| Albumin mean ± SD | -- | -- | 3.03 ± 0.83 | 2.45 ± 0.49 | 0.375 | 2.87 ± 0.55 | 2.83 ± 0.66 | 0.901 | 2.95 ± 0.69 | 2.34 ± 0.72 | 0.017 | |

| Surgery specific cause | 0.084 | 0.259 | 0.074 | 0.286 | ||||||||

| Obstruction, n (%) | 39 (29.9) | 3 (60) | 50 (44.2) | 4 (28.6) | 43 (51.8) | 10 (30.3) | 75 (58.1) | 37 (48.1) | ||||

| Perforation, n (%) | 65 (44.8) | 1 (20) | 40 (35.4) | 5 (35.7) | 28 (33.7) | 18 (54.5) | 37 (28.7) | 22 (28.6) | ||||

| Ischemia, n (%) | 3 (2.1) | 1 (20) | 9 (8.0) | 4 (28.6) | 5 (6.0) | 5 (15.2) | 11 (8.5) | 11 (14.3) | ||||

| Infection, n (%) | 16 (11.0) | 0 (0) | 9 (8.0) | 1 (7.1) | 4 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 5 (3.9) | 4 (5.2) | ||||

| Inflammation, n (%) | 21 (14.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Bleeding, n (%) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (3.9) | ||||

| 18–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | ≥80 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables in the Model | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p Value | Variables in the Model | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p Value | Variables in the Model | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p Value | Variables in the Model | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p Value |

| WBC | 1.215 | 1.040–1.421 | 0.014 | ASA | 2.459 | 1.057–5.72 | 0.037 | ASA | 2.428 | 1.085–5.43 | 0.031 | ASA | 1.503 | 0.139–16.29 | 0.738 |

| ASA | 2.675 | 0.943–7.584 | 0.064 | ADL | 6.773 | 1.652–27.76 | 0.008 | ADL | 9.664 | 1.536–60.79 | 0.016 | ADL | 2.030 | 0.119–34.49 | 0.624 |

| Blood transfusion | 2.156 | 0.219–21.194 | 0.510 | Dementia | 1.113 | 0.123- 10.08 | 0.924 | Dementia | 0.848 | 0.089–8.04 | 0.886 | Dementia | 3.988 | 0.150–105.78 | 0.408 |

| Specific cause | 0.258 | 0.052–1.270 | 0.096 | Hemoglobin | 0.841 | 0.612- 1.15 | 0.288 | Creatinine | 1.344 | 0.894–2.02 | 0.155 | Cancer | 2.370 | 0.083–67.309 | 0.613 |

| Dementia | 13.164 | 0.722–240.149 | 0.082 | WBC | 1.285 | 0.982–1.681 | 0.068 | ||||||||

| Creatinine | 4.169 | 0.617–28.16 | 0.143 | ||||||||||||

| Albumin | 0.050 | 0.002–1.112 | 0.058 | ||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kent, I.; Ghuman, A.; Sadran, L.; Rov, A.; Lifschitz, G.; Rudnicki, Y.; White, I.; Goldberg, N.; Avital, S. Emergency Colectomies in the Elderly Population—Perioperative Mortality Risk-Factors and Long-Term Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2465. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12072465

Kent I, Ghuman A, Sadran L, Rov A, Lifschitz G, Rudnicki Y, White I, Goldberg N, Avital S. Emergency Colectomies in the Elderly Population—Perioperative Mortality Risk-Factors and Long-Term Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(7):2465. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12072465

Chicago/Turabian StyleKent, Ilan, Amandeep Ghuman, Luna Sadran, Adi Rov, Guy Lifschitz, Yaron Rudnicki, Ian White, Nitzan Goldberg, and Shmuel Avital. 2023. "Emergency Colectomies in the Elderly Population—Perioperative Mortality Risk-Factors and Long-Term Outcomes" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 7: 2465. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12072465

APA StyleKent, I., Ghuman, A., Sadran, L., Rov, A., Lifschitz, G., Rudnicki, Y., White, I., Goldberg, N., & Avital, S. (2023). Emergency Colectomies in the Elderly Population—Perioperative Mortality Risk-Factors and Long-Term Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(7), 2465. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12072465