Specific Learning Disabilities and Emotional-Behavioral Difficulties: Phenotypes and Role of the Cognitive Profile

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

- A deficient score (z score ≤−2 or percentage rank ≤5°) in at least two reading aloud tests and/or dictation test and/or mathematics test.

2.2. Assessment Procedure

2.2.1. Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)

2.2.2. Intelligence

2.2.3. Academic Abilities

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Academic and Cognitive Profile

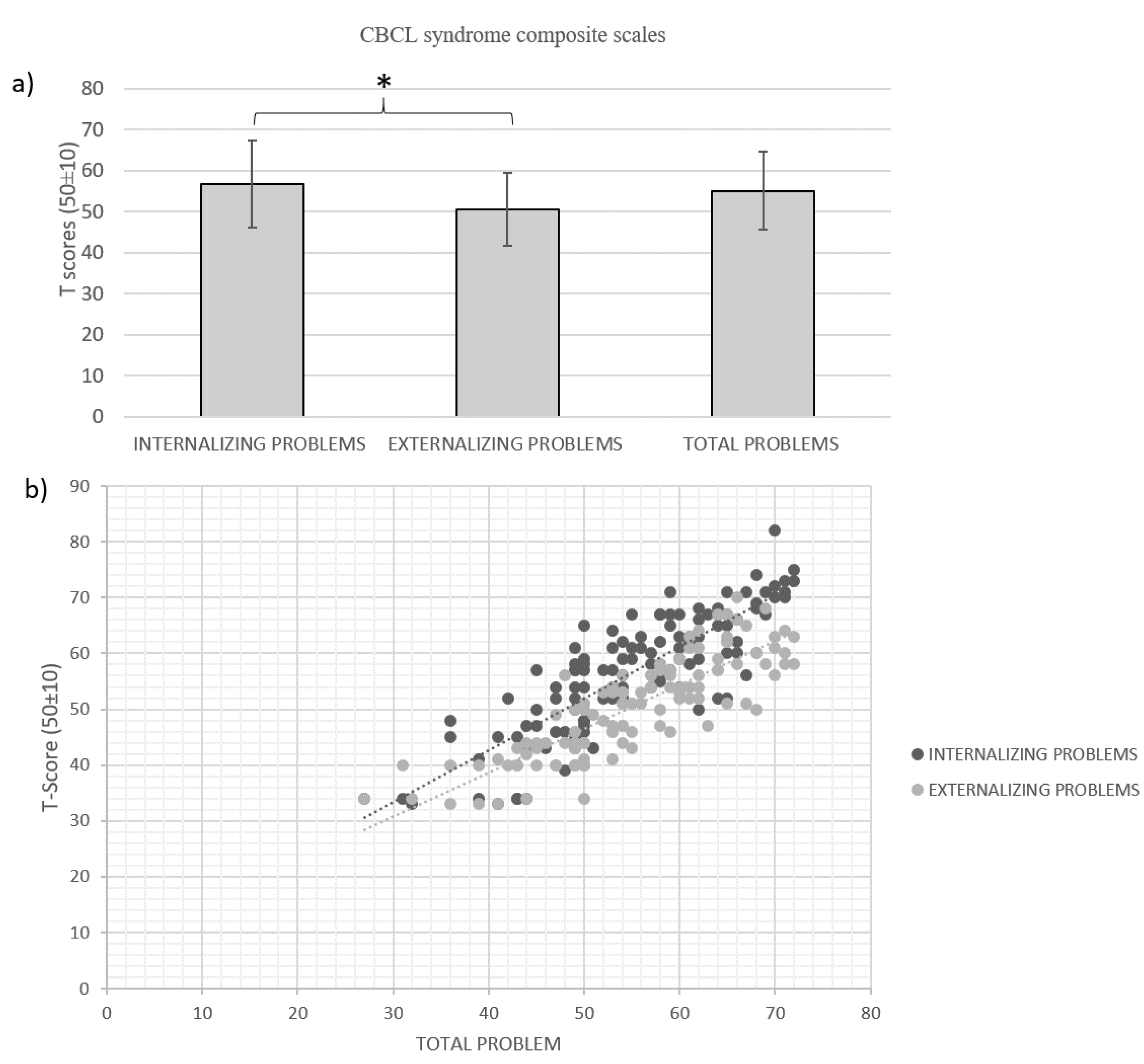

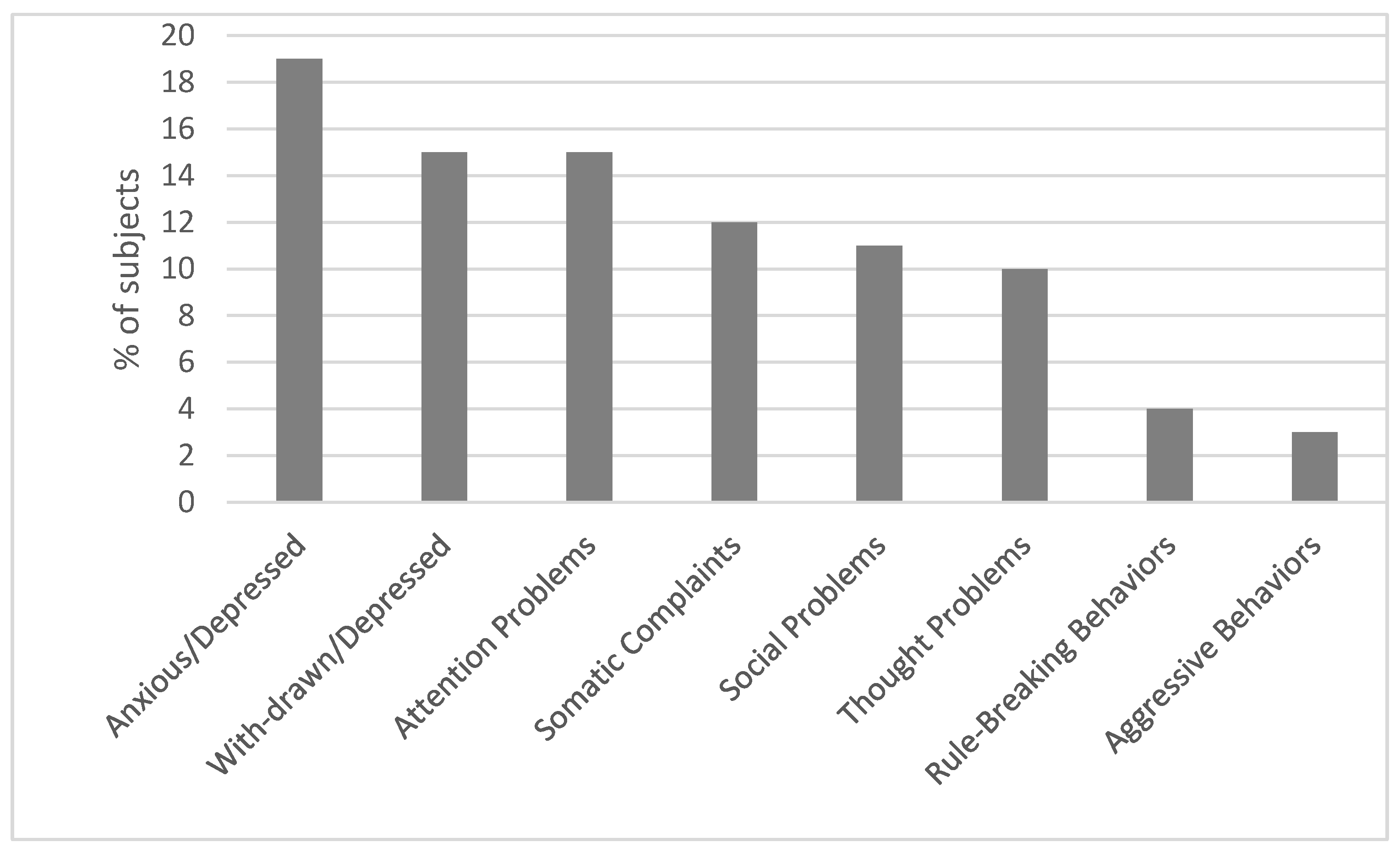

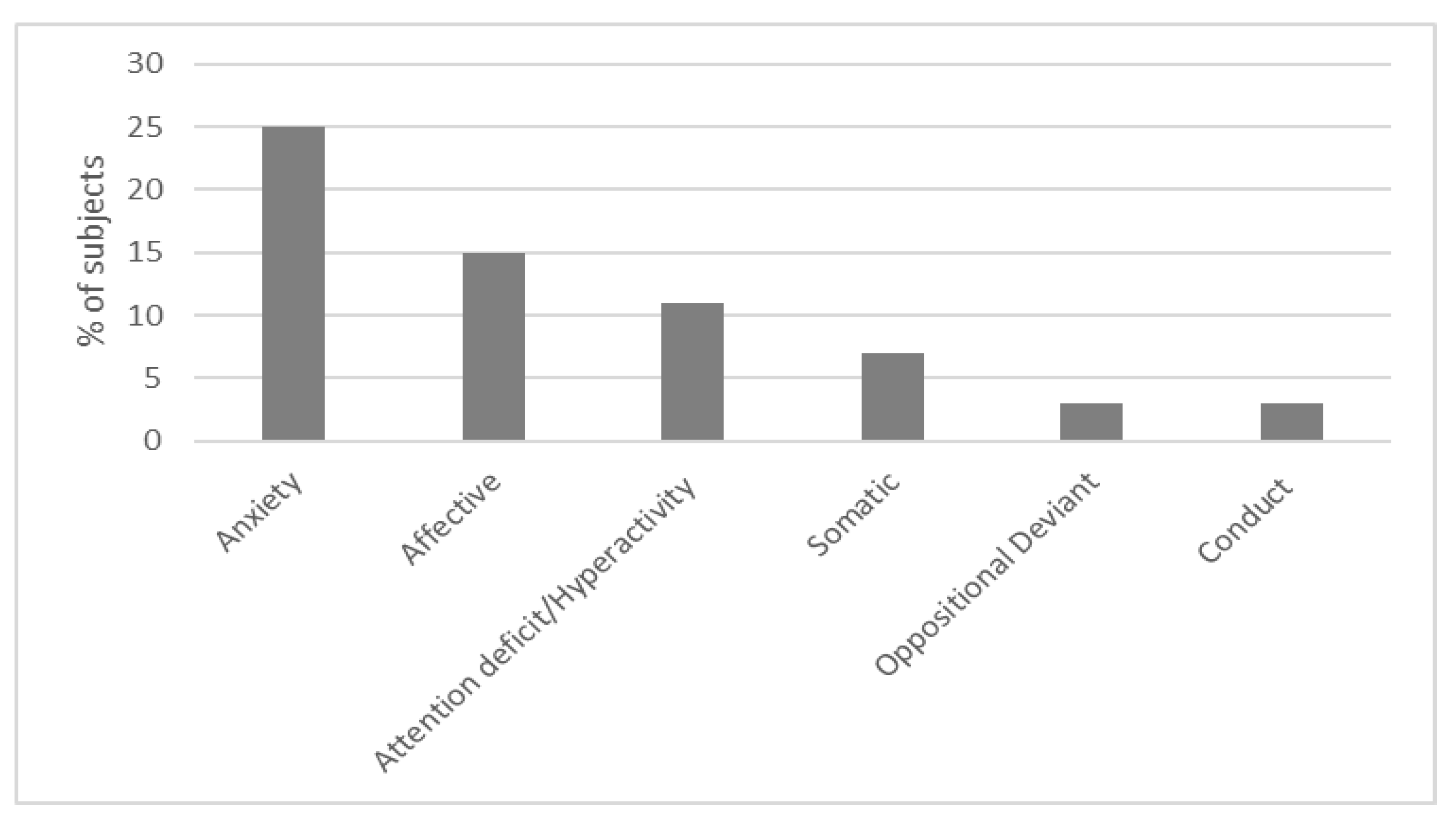

3.2. Behavioral and Emotional Characteristics

3.3. Relationships and Interactions among the Background, Learning, Cognitive, and Emotional Characteristics

3.3.1. Relationship with the Background Characteristics

3.3.2. Relationship with the Cognitive Profile

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; DSM-5 TM. [Google Scholar]

- Mayes, S.D.; Calhoun, S.L.; Crowell, E.W. Learning disabilities and ADHD: Overlapping spectrum disorders. J. Learn. Disabil. 2000, 33, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willcutt, E.G.; Pennington, B.F. Psychiatric Comorbidity in Children and Adolescents with Reading Disability. J Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2000, 41, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maughan, B.; Rowe, R.; Loeber, R.; Stouthamer-Loeber, M. Reading Problems and Depressed Mood. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2003, 31, 219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Margari, L.; Buttiglione, M.; Craig, F.; Cristella, A.; de Giambattista, C.; Matera, E.; Operto, F.; Simone, M. Neuropsychopathological comorbidities in learning disorders. BMC Neurol. 2013, 13, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammarella, I.C.; Ghisi, M.; Bomba, M.; Bottesi, G.; Caviola, S.; Broggi, F.; Nacinovich, R. Anxiety and depression in children with nonverbal learning disabilities, reading disabilities, or typical development. J. Learn. Disabil. 2016, 49, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, L.; Kalmar, J.; Linkersdörfer, J.; Görgen, R.; Rothe, J.; Hasselhorn, M.; Schulte-Körne, G. Comorbidities Between Specific Learning Disorders and Psychopathology in Elementary School Children in Germany. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.; Lind, S. Comorbidity and diagnosis of developmental disorders. In Current Issues in Developmental Psychology; Marshall, C., Ed.; Psychology Press Editor: London, UK, 2013; pp. 19–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gooch, D.; Hulme, C.; Nash, H.M.; Snowling, M.J. Comorbidities in preschool children at family risk of dyslexia. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J.M.; Maughan, B.; Goodman, R.; Meltzer, H. Literacy difficulties and psychiatric disorders: Evidence for comorbidity. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2005, 46, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, R.; Williams, S.; Share, D.L.; Anderson, J.; Silva, P.A. The relationship between Specific Reading Retardation, General Reading Backwardness and Behavioural Problems in a large sample of Dunedin Boys: A longitudinal study from five to eleven years. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1986, 27, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, M.; Smart, D.; Sanson, A.; Oberklaid, F. Relationships between learning difficulties and psychological problems in preadolescent children from a longitudinal sample. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1999, 38, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Edelbrock, C.S. The classification of child psychopathology: A review and analysis of empirical efforts. Psychol. Bull. 1978, 85, 1275–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marianelli, C.V.; Romano, G.; Cristalli, I.; Franzese, A.; Di Filippo, G. Autostima, stile attributivo e disturbi internalizzanti in bambini dislessici. Dislessia 2016, 13, 297–310. [Google Scholar]

- Altay, M.A.; Görker, I. Assessment of psychiatric comorbidity and WISC-R profiles in cases diagnosed with specific learning disorder according to DSM-5 criteria. Arch. Neuropsychiatry 2018, 55, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Huc-Chabrolle, M.; Barthez, M.A.; Tripi, G.; Barthélémy, C.; Bonnet-Brilhault, F. Psychocognitive and psychiatric disorders associated with developmental dyslexia: A clinical and scientific issue. Encephale 2010, 36, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.; Patil, V.; Sagar, R.; Bhargava, R. Psychiatric comorbidities in children with Specific Learning Disorder-Mixed Type: A cross-sectional study. J. Neurosci. Rural Pract. 2019, 10, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, J.; Mayer, A.; Scharke, W.; Heim, S.; Günther, T. Development of Behavior Problems in Children with and without Specific Learning Disorders in Reading and Spelling from Kindergarten to Fifth Grade. Sci. Stud. Read 2020, 24, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuPaul, G.J.; Gormley, M.J.; Laracy, S.D. Comorbidity of LD and ADHD: Implications of DSM-5 for Assessment and Treatment. J. Learn. Disabil. 2013, 46, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Côte-Sainte-Catherine, C. ADHD and comorbid disorders in childhood psychiatric problems, medical problems, learning disorders and developmental coordination. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2015, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, B.F. From single to multiple deficit models of developmental disorders. Cognition 2006, 101, 385–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovagnoli, S.; Mandolesi, L.; Magri, S.; Gualtieri, L.; Fabbri, D.; Tossani, E.; Benassi, M. Internalizing Symptoms in Developmental Dyslexia: A Comparison Between Primary and Secondary School. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palombo, J. Learning Disorders & Disorders of the Self in Children & Adolescents; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzoli, C.; Lami, L.; Calmieri, A.; Solimando, M.C. Dislessia e fattori psicosociali: Percorso accademico e benessere psicosociale in due campioni di dislessici giovani adulti. Psicol. Clin. Dello Sviluppo 2011, 4, 95–122. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty, M.A. Dyslexia and the life course. J. Learn. Disabil. 2003, 36, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, S. Beyond a “culture of silence”: Inclusive education and the liberation of “voice”. Disabil. Soc. 2006, 21, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugnaini, D.; Lassi, S.; La Malfa, G.; Albertini, G. Internalizing correlates of dyslexia. World J. Pediatr. 2009, 5, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nachshon, O.; Horowitz-Kraus, T. Cognitive and emotional challenges in children with reading difficulties. Acta Paediatr. 2019, 108, 1110–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiervang, E.; Lund, A.; Stevenson, J.; Hugdahl, K. Behaviour problems in children with dyslexia. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2001, 55, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brizzolara, D.; Gasperini, F.; Pfanner, L.; Cristofani, P.; Casalini, C.; Chilosi, A. Long-term reading and spelling outcome in Italian adolescents with a history of specific language impairment. Cortex 2011, 47, 955–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalini, C.; Brizzolara, D.; Chilosi, A.M.; Gasperini, F.; Pecini, C. Late effects of early language delay on complex language and literacy abilities: A clinical approach to dyslexia in subjects with a previous language impairment. In A Linguistic Approach to the Study of Dyslexia; Cappelli, G., Noccetti, S., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2022; pp. 66–86. [Google Scholar]

- Tomblin, J.B.; Zhang, X.; Buckwalter, P.; Catts, H. The Association of Reading Disability, Behavioral Disorders, and Language Impairment among Second-grade Children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2000, 41, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durkin, K.; Conti-Ramsden, G. Language, social behavior, and the quality of friendships in adolescents with and without a history of specific language impairment. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 1441–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti-Ramsden, G.; Durkin, K.; Toseeb, U.; Botting, N.; Pickles, A. Education and employment outcomes of young adults with a history of developmental language disorder. Int. J. Lang Commun. Disord. 2018, 53, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bedem, N.P.; Dockrell, J.E.; van Alphen, P.M.; de Rooij, M.; Samson, A.C.; Harjunen, E.L.; Rieffe, C. Depressive symptoms and emotion regulation strategies in children with and without developmental language disorder: A longitudinal study. Int. J. Lang Commun. Disord. 2018, 53, 1110–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundheim, S.T.P.V.; Voeller, K.K.S. Psychiatric implications of language disorders and learning disabilities: Risks and management. J. Child Neurol. 2004, 19, 814–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems ICD-10: Tenth Revision, 5th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/246208 (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Panel di Aggiornamento e Revisione della Consensus Conference DSA—P.A.R.C.C. Raccomandazioni Cliniche sui DSA Documento D’intesa in Risposta a Quesiti Sui Disturbi Evolutivi Specifici Dell’apprendimento. 2011. Available online: www.lineeguidadsa.it (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) Technical and Interpretive Manual; The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV) Technical and Interpretative Manual; Pearson: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Orsini, A.; Pezzuti, L.; Picone, L. WISC-IV: Contributo Alla Taratura Italiana; Giunti OS: Firenze, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Orsini, A.; Pezzuti, L. WAIS-IV. Contributo Alla Taratura Italiana; Giunti OS: Firenze, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lorusso, M.; Vernice, M.; Dieterich, M.; Brizzolara, D.; Mariani, E.; De Masi, S.; D’Angelo, F.; Lacorte, E.; Mele, A. The process and criteria for diagnosing specific learning disorders: Indications from the Consensus Conference promoted by the Italian National Institute of Health. Ann. Dell’Istituto Super. Di Sanità 2014, 50, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.M. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile; University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry: Burlington, VT, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Rescorla, L. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles: An Integrated SYSTEM of Multi-Informant Assessment; ASEBA: Burlington, VT, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chilosi, A.M.; Brizzolara, D.; Lami, L.; Pizzoli, C.; Gasperini, F.; Pecini, C.; Cipriani, P.; Zoccolotti, P. Reading and spelling disabilities in children with and without a history of early language delay: A neuropsychological and linguistic study. Child Neuropsychol. 2009, 15, 582–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, A.; Cattaneo, C.; Cataldo, M.; Schiatti, A.; Molteni, M.; Battaglia, M. Behavioral and Emotional Problems Among Italian Children and Adolescents Aged 4 to 18 Years as Reported by Parents and Teachers. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess 2004, 20, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, A.; Rucci, P.; Goodman, R.; Ammaniti, M.; Carlet, O.; Cavolina, P.; de Girolamo, G.; Lenti, C.; Lucarelli, L.; Mani, E.; et al. Prevalence and correlates of mental disorders among adolescents in Italy: The PrISMA study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2009, 18, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritti, A.; Bravaccio, C.; Signoriello, S.; Salerno, F.; Pisano, S.; Catone, G.; Gallo, C.; Pascotto, A. Epidemiological study on behavioural and emotional problems in developmental age: Prevalence in a sample of Italian children, based on parent and teacher reports. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2014, 40, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Althoff, R.R.; Ayer, L.A.; Rettew, D.C.; Hudziak, J.J. Assessment of Dysregulated Children Using the Child Behavior Checklist: A Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve Analysis. Psychol. Assess 2010, 22, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, M.; Battaglia, M.; Marino, C.; Mahendran, N.; Andrade, B.F. Clinical utility of the CBCL Dysregulation Profile in children with disruptive behavior. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 253, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornoldi, C.; Colpo, G. Nuove Prove di Lettura MT; Organizzazioni Speciali: Firenze, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cornoldi, C.; Colpo, G.; Gruppo, M.T. Nuove Prove di Lettura MT; Giunti OS: Firenze, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cornoldi, C.; Pra Baldi, A.; Friso, G.; Giacomin, A.; Giofrè, D.; Zaccaria, S. Prove di Lettura MT Avanzate-2. Prove MT Avanzate di Lettura e Matematica 2 per il Biennio Della Scuola Secondaria di Secondo Grado; Giunti OS: Firenze, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sartori, G.; Job, R. DDE-2: Batteria per la Valutazione Della Dislessia e Della Disortografia Evolutiva-2; Giunti OS: Firenze, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tressoldi, P.E.; Cornoldi, C.; Re, A.M. BVSCO-2. Batteria per la Valutazione Della Scrittura e Della Competenza Ortografica-2; Giunti Edu: Firenze, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Biancardi, A.; Nicoletti, C.; Bachmann, C. BDE 2-Batteria Discalculia Evolutiva: Test per la Diagnosi dei Disturbi Dell’elaborazione numerica e del Calcolo in età Evolutiva–8-13 Anni; Edizioni Centro Studi Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, B.; Kaplan, D. A comparison of some methodologies for the factor analysis of non-normal Likert variables. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 1985, 38, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanca Mena, M.J.; Alrcòn Postigo, M.; Arnau Gras, J.; Bono Cabré, R.; Bendayan, R. Non-normal data: Is ANOVA still a valid option? Psicothema 2017, 29, 552–557. [Google Scholar]

- Bäcker, A.; Neuhäuser, G. Internalizing and externalizing syndrome in reading and writing disorders. Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr. 2003, 52, 329–337. [Google Scholar]

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità—ISS Linea Guida Sulla Gestione dei Disturbi Specifici di Apprendimento (DSA). Aggiornamento e Integrazioni. 2021. Available online: Snlg.iss.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/LG-389-AIP_DSA.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Giofrè, D.; Borella, E.; Mammarella, I.C. The relationship between intelligence, working memory, academic self-esteem, and academic achievement. Cogn. Psychol. 2017, 29, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffalini, E.; Marsura, M.; Garcia, R.B.; Cornoldi, C. A cross-modal working memory binding span deficit in reading disability. J. Learn. Disabil. 2019, 52, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avenevoli, S.; Swendsen, J.; He, J.P.; Burstein, M.; Merikangas, K. Major depression in the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement: Prevalences, Correlates, and Treatment. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 54, 37–44.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Acunto, M.G.; Masi, G. Disturbi dell’umore. In Disturbi e Traiettorie Atipiche del Neurosviluppo. Diagnosi e Intervento; Pecini, C., Brizzolara, D., Eds.; McGrawHill: Milano, Italy, 2020; pp. 377–395. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, S.M.; Park, J.; Seth, S.; Coghill, D.R. A comprehensive investigation of memory impairment in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. J Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peijnenborgh, J.C.; Hurks, P.M.; Aldenkamp, A.P.; Vles, J.S.; Hendriksen, J.G. Efficacy of working memory training in children and adolescents with learning disabilities: A review study and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2016, 26, 645–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capodieci, A.; Romano, M.; Castro, E.; Di Lieto, M.C.; Bonetti, S.; Spoglianti, S.; Pecini, C. Executive Functions and Rapid Automatized Naming: A New Tele-Rehabilitation Approach in Children with Language and Learning Disorders. Children 2022, 9, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibzadeh, A.; Pourabdol, S.; Saravani, S. The effect of emotion regulation training in decreasing emotion failures and self-injurious behaviors among students suffering from specific learning disorder (SLD). Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2015, 29, 279. [Google Scholar]

- Terras, M.M.; Thompson, L.C.; Minnis, H. Dyslexia and psycho-social functioning: An exploratory study of the role of self-esteem and understanding. Dyslexia 2009, 15, 304–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmot, A.; Hasking, P.; Leitão, S.; Hill, E.; Boyes, M. Understanding Mental Health in Developmental Dyslexia: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Text Decoding Accuracy | Text Decoding Speed | Text Comprehension Accuracy | Text Dictation Accuracy | Sentences Dictation Accuracy | Math Quotient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Interquartile Differences | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| N | Minimum | Maximum | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VCI | 117 | 70 | 124 | 98.90 | 11,724 |

| PRI | 118 | 65 | 141 | 101.58 | 13,145 |

| WMI | 115 | 55 | 115 | 84.83 | 13,543 |

| PSI | 115 | 53 | 138 | 90.99 | 13,646 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cristofani, P.; Di Lieto, M.C.; Casalini, C.; Pecini, C.; Baroncini, M.; Pessina, O.; Gasperini, F.; Dasso Lang, M.B.; Bartoli, M.; Chilosi, A.M.; et al. Specific Learning Disabilities and Emotional-Behavioral Difficulties: Phenotypes and Role of the Cognitive Profile. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1882. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12051882

Cristofani P, Di Lieto MC, Casalini C, Pecini C, Baroncini M, Pessina O, Gasperini F, Dasso Lang MB, Bartoli M, Chilosi AM, et al. Specific Learning Disabilities and Emotional-Behavioral Difficulties: Phenotypes and Role of the Cognitive Profile. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(5):1882. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12051882

Chicago/Turabian StyleCristofani, Paola, Maria Chiara Di Lieto, Claudia Casalini, Chiara Pecini, Matteo Baroncini, Ottavia Pessina, Filippo Gasperini, Maria Bianca Dasso Lang, Mariaelisa Bartoli, Anna Maria Chilosi, and et al. 2023. "Specific Learning Disabilities and Emotional-Behavioral Difficulties: Phenotypes and Role of the Cognitive Profile" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 5: 1882. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12051882

APA StyleCristofani, P., Di Lieto, M. C., Casalini, C., Pecini, C., Baroncini, M., Pessina, O., Gasperini, F., Dasso Lang, M. B., Bartoli, M., Chilosi, A. M., & Milone, A. (2023). Specific Learning Disabilities and Emotional-Behavioral Difficulties: Phenotypes and Role of the Cognitive Profile. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(5), 1882. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12051882