Poor Adherence to Self-Applied Topical Drug Treatment Is a Common Source of Low Lesion Clearance in Patients with Actinic Keratosis—A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Study Population

2.2. Description of the Questionnaire

2.3. Subgroup Selection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sinikumpu, S.P.; Jokelainen, J.; Haarala, A.K.; Keranen, M.H.; Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi, S.; Huilaja, L. The High Prevalence of Skin Diseases in Adults Aged 70 and Older. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 2565–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schipani, G.; Del Duca, E.; Todaro, G.; Scali, E.; Dastoli, S.; Bennardo, L.; Bonacci, S.; Pavel, A.B.; Colica, C.; Xu, X.; et al. Arsenic and chromium levels in hair correlate with actinic keratosis/non-melanoma skin cancer: Results of an observational controlled study. G. Ital. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 156, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criscione, V.D.; Weinstock, M.A.; Naylor, M.F.; Luque, C.; Eide, M.J.; Bingham, S.F. Department of Veteran Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial Group. Actinic keratoses: Natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial. Cancer 2009, 115, 2523–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heppt, M.V.; Leiter, U.; Steeb, T.; Amaral, T.; Bauer, A.; Becker, J.C.; Breitbart, E.; Breuninger, H.; Diepgen, T.; Dirschka, T.; et al. S3 guideline for actinic keratosis and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma—Short version, part 1: Diagnosis, interventions for actinic keratoses, care structures and quality-of-care indicators. JDDG J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2020, 18, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, E.A.T.; Wessely, A.; Steeb, T.; Berking, C.; Heppt, M.V. Safety of topical interventions for the treatment of actinic keratosis. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2021, 20, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steeb, T.; Wessely, A.; Harlass, M.; Heppt, F.; Koch, E.A.T.; Leiter, U.; Garbe, C.; Schoffski, O.; Berking, C.; Heppt, M.V. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Interventions for Actinic Keratosis from Post-Marketing Surveillance Trials. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijsten, T.; Colpaert, C.G.; Vermeulen, P.B.; Harris, A.L.; Van Marck, E.; Lambert, J. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression and angiogenesis in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin and its precursors: A paired immunohistochemical study of 35 cases. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004, 151, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.M.; He, G.; Hwang, D.H.; Fischer, S.M. Overexpression of the prostaglandin E2 receptor EP2 results in enhanced skin tumor development. Oncogene 2006, 25, 5507–5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, A.C.; Milton, F.A.; Cvoro, A.; Sieglaff, D.H.; Campos, J.C.; Bernardes, A.; Filgueira, C.S.; Lindemann, J.L.; Deng, T.; Neves, F.A.; et al. Mechanisms of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma regulation by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Nucl. Recept. Signal. 2015, 13, e004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwan, L.E.; Smith, J.G. Topical diclofenac/hyaluronic acid gel in the treatment of solar keratoses. Australas. J. Dermatol. 1997, 38, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockfleth, E.; Kerl, H.; Zwingers, T.; Willers, C. Low-dose 5-fluorouracil in combination with salicylic acid as a new lesion-directed option to treat topically actinic keratoses: Histological and clinical study results. Br. J. Dermatol. 2011, 165, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, S.; Furst, K.; Chern, W. A pharmacokinetic evaluation of 0.5% and 5% fluorouracil topical cream in patients with actinic keratosis. Clin. Ther. 2001, 23, 908–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.L.; Gerster, J.F.; Owens, M.L.; Slade, H.B.; Tomai, M.A. Imiquimod applied topically: A novel immune response modifier and new class of drug. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 1999, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neugebauer, R.; Levandoski, K.A.; Zhu, Z.; Sokil, M.; Chren, M.M.; Friedman, G.D.; Asgari, M.M. A real-world, community-based cohort study comparing the effectiveness of topical fluorouracil versus topical imiquimod for the treatment of actinic keratosis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilu, D.; Sauder, D.N. Imiquimod: Modes of action. Br. J. Dermatol. 2003, 149 (Suppl. S66), 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, M.V. Imiquimod: A cytokine inducer. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2002, 47, S205–S208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeimies, R.M.; Gerritsen, M.J.; Gupta, G.; Ortonne, J.P.; Serresi, S.; Bichel, J.; Lee, J.H.; Fox, T.L.; Alomar, A. Imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of actinic keratosis: Results from a phase III, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, clinical trial with histology. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2004, 51, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, D. Topical imiquimod: Mechanism of action and clinical applications. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2006, 6, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolinski, M.P.; Bu, Y.; Clements, J.; Gelman, I.H.; Hegab, T.; Cutler, D.L.; Fang, J.W.S.; Fetterly, G.; Kwan, R.; Barnett, A.; et al. Discovery of Novel Dual Mechanism of Action Src Signaling and Tubulin Polymerization Inhibitors (KX2-391 and KX2-361). J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 4704–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blauvelt, A.; Kempers, S.; Lain, E.; Schlesinger, T.; Tyring, S.; Forman, S.; Ablon, G.; Martin, G.; Wang, H.; Cutler, D.L.; et al. Phase 3 Trials of Tirbanibulin Ointment for Actinic Keratosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Dobbeler, C.; Schmitz, L.; Dicke, K.; Szeimies, R.M.; Dirschka, T. PDT with PPIX absorption peaks adjusted wavelengths: Safety and efficacy of a new irradiation procedure for actinic keratoses on the head. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 27, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pflugfelder, A.; Welter, A.K.; Leiter, U.; Weide, B.; Held, L.; Eigentler, T.K.; Dirschka, T.; Stockfleth, E.; Nashan, D.; Garbe, C.; et al. Open label randomized study comparing 3 months vs. 6 months treatment of actinic keratoses with 3% diclofenac in 2.5% hyaluronic acid gel: A trial of the German Dermatologic Cooperative Oncology Group. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2012, 26, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.; Piacquadio, D.; Morhenn, V.; Atkin, D.; Fitzpatrick, R. Short incubation PDT versus 5-FU in treating actinic keratoses. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2003, 2, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, R.; Spelman, L.; Weightman, W.; Reifenberger, J.; Szeimies, R.M.; Verhaeghe, E.; Kerrouche, N.; Sorba, V.; Villemagne, H.; Rhodes, L.E. Multicentre intraindividual randomized trial of topical methyl aminolaevulinate-photodynamic therapy vs. cryotherapy for multiple actinic keratoses on the extremities. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008, 158, 994–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M.H.E.; Kessels, J.; Nelemans, P.J.; Kouloubis, N.; Arits, A.; van Pelt, H.P.A.; Quaedvlieg, P.J.F.; Essers, B.A.B.; Steijlen, P.M.; Kelleners-Smeets, N.W.J.; et al. Randomized Trial of Four Treatment Approaches for Actinic Keratosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 935–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollnick, H.; Dirschka, T.; Ostendorf, R.; Kerl, H.; Kunstfeld, R. Long-term clinical outcomes of imiquimod 5% cream vs. diclofenac 3% gel for actinic keratosis on the face or scalp: A pooled analysis of two randomized controlled trials. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, P.; Stockfleth, E.; Peris, K.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Cerio, R.; Antonio Sanches, J.; Guillen, C.; Farrington, E.; Lebwohl, M. Adherence to topical therapies in actinic keratosis: A literature review. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2016, 27, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shergill, B.; Zokaie, S.; Carr, A.J. Non-adherence to topical treatments for actinic keratosis. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2013, 8, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M.H.E.; Kessels, J.; Merks, I.; Nelemans, P.J.; Kelleners-Smeets, N.W.J.; Mosterd, K.; Essers, B.A.B. A trial-based cost-effectiveness analysis of topical 5-fluorouracil vs. imiquimod vs. ingenol mebutate vs. methyl aminolaevulinate conventional photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis in the head and neck area performed in the Netherlands. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 183, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erntoft, S.; Norlin, J.M.; Pollard, C.; Diepgen, T.L. Patient-reported adherence and persistence to topical treatments for actinic keratosis: A longitudinal diary study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2016, 175, 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardwell, L.A.; Feldman, S.R. Adherence to topical treatments for actinic keratosis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2016, 175, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgouros, D.; Milia-Argyti, A.; Arvanitis, D.K.; Polychronaki, E.; Kousta, F.; Panagiotopoulos, A.; Theotokoglou, S.; Syrmali, A.; Theodoropoulos, K.; Stratigos, A.; et al. Actinic Keratoses (AK): An Exploratory Questionnaire-Based Study of Patients’ Illness Perceptions. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 5150–5163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershman, D.L.; Kushi, L.H.; Hillyer, G.C.; Coromilas, E.; Buono, D.; Lamerato, L.; Bovbjerg, D.H.; Mandelblatt, J.S.; Tsai, W.Y.; Zhong, X.; et al. Psychosocial factors related to non-persistence with adjuvant endocrine therapy among women with breast cancer: The Breast Cancer Quality of Care Study (BQUAL). Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2016, 157, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebovits, A.H.; Strain, J.J.; Schleifer, S.J.; Tanaka, J.S.; Bhardwaj, S.; Messe, M.R. Patient noncompliance with self-administered chemotherapy. Cancer 1990, 65, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Clark, R.; Tu, P.; Bosworth, H.B.; Zullig, L.L. Breast cancer oral anti-cancer medication adherence: A systematic review of psychosocial motivators and barriers. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 165, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makubate, B.; Donnan, P.T.; Dewar, J.A.; Thompson, A.M.; McCowan, C. Cohort study of adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy, breast cancer recurrence and mortality. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, F.; Harris, P.; Waller, H.; Coggins, A. Adherence to an exercise prescription scheme: The role of expectations, self-efficacy, stage of change and psychological well-being. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, L.C.; Goyer, J.P.; Crum, A.J. Harnessing the placebo effect: Exploring the influence of physician characteristics on placebo response. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 1074–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, A.M.; Anderson, K.L.; Feldman, S.R. Interventions to Increase Treatment Adherence in Pediatric Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2015, 4, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, F.; Weber, C.; Berking, C.; Schadendor, D.; Steeb, T.; Doppler, A. Die NVKH launcht das Informationsportal Hautkrebs. JDDG J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2021, 19, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C.L.; Feldman, S.R.; Camacho, F.T.; Manuel, J.C.; Balkrishnan, R. Adherence to topical therapy decreases during the course of an 8-week psoriasis clinical trial: Commonly used methods of measuring adherence to topical therapy overestimate actual use. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2004, 51, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographics | Median (Range) | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 78.5 (58–94) | 110 | 97.3 | |

| Missing | 3 | 2.7 | ||

| Gender | Male | 95 | 84.1 | |

| Female | 16 | 14.2 | ||

| Missing | 2 | 1.8 | ||

| Marital status | Single | 5 | 4.4 | |

| Married | 82 | 72.6 | ||

| Divorced | 5 | 4.4 | ||

| Widowed | 19 | 16.8 | ||

| Missing | 2 | 1.8 | ||

| Insurance | Statutory | 84 | 74.3 | |

| Private | 26 | 23 | ||

| Missing | 3 | 2.7 | ||

| Education | No degree | 1 | 0.9 | |

| Secondary school (lower) | 42 | 37.2 | ||

| Secondary school (higher) | 20 | 17.7 | ||

| High school | 8 | 7.1 | ||

| University/college | 38 | 33.6 | ||

| Missing | 4 | 3.5 | ||

| Topical drug | 5-Fluoruracil 0.5% and salicylic acid 10% solution | 9 | 8 | |

| Imiquimod cream 5% or 3.75% | 10 | 8.8 | ||

| Diclofenac natrium gel 3% in hyaluronic acid 2.5% gel | 54 | 47.8 | ||

| 5-Fluoruracil cream 5% | 9 | 8 | ||

| Photodynamic therapy | 8 | 7.1 | ||

| >1 treatment | 9 | 8 | ||

| Missing | 14 | 12.4 | ||

| Number of AKs | 1–5 AKs | 46 | 40.7 | |

| 5–10 AKs | 35 | 31 | ||

| >10 AKs | 22 | 19.5 | ||

| Missing | 10 | 8.8 | ||

| Localization | Scalp | 49 | 43.4 | |

| Trunk | 2 | 1.8 | ||

| Face | 26 | 23 | ||

| Extremities | 8 | 7.1 | ||

| >1 incl. head | 24 | 21.2 | ||

| >1 excl. head | 4 | 3.5 | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | ||

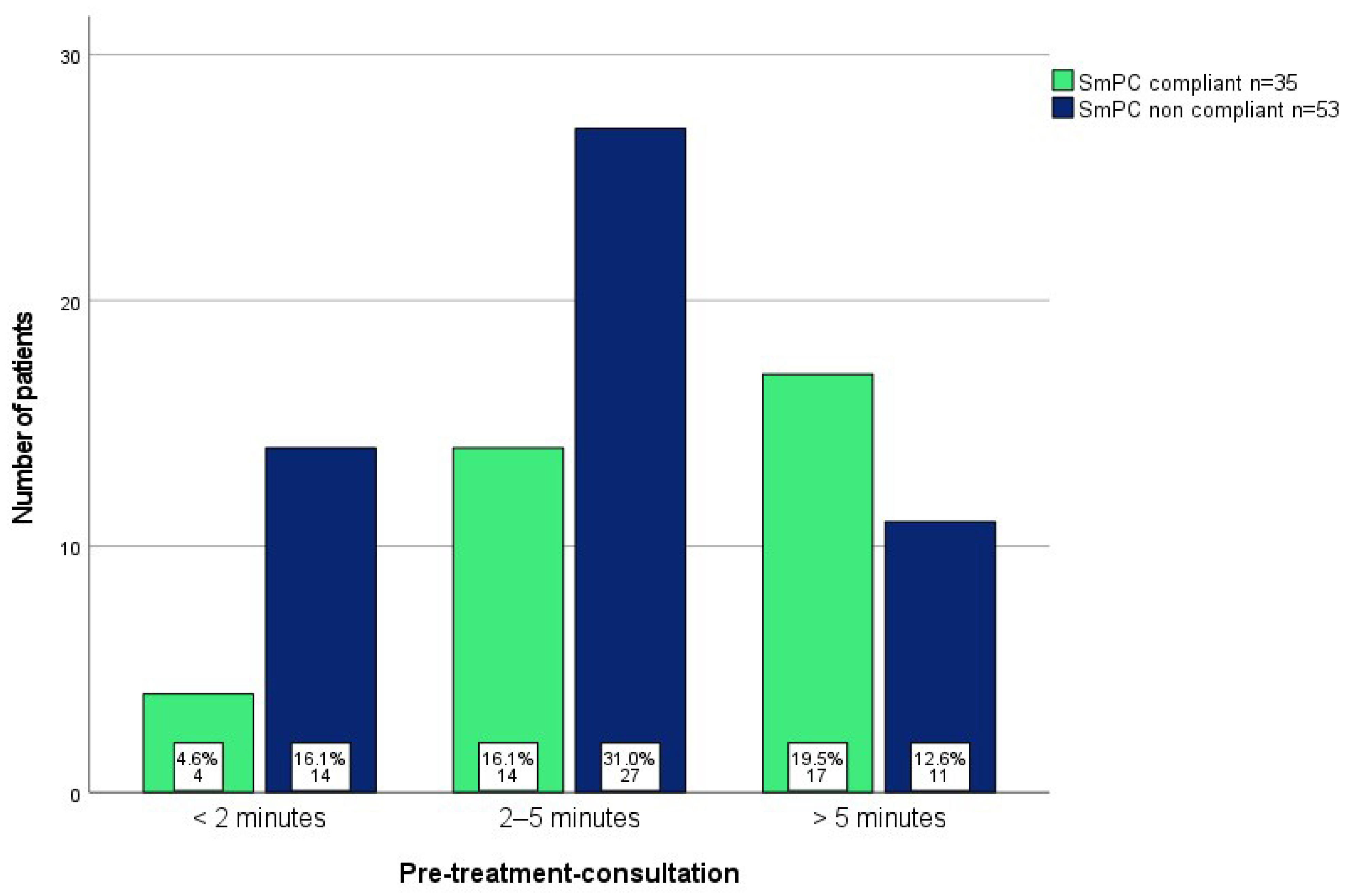

| Drug use | SmPc-compliant | 53 | 31 | |

| SmPC-non-compliant | 35 | 46.9 | ||

| Missing | 25 | 22.1 | ||

| Duration of pre-treatment consultation | <2 min | 22 | 19.5 | |

| 2–5 min | 53 | 46.9 | ||

| >5 min | 32 | 28.3 | ||

| Missing | 6 | 5.3 | ||

| Consultation in the treatment follow-up | No consultation | 42 | 37.2 | |

| Consultation | 64 | 56.6 | ||

| Missing | 7 | 6.2 | ||

| Time interval of consultation in the treatment follow-up | <2 weeks | 2 | 3.13 | |

| 1–2 months | 14 | 21.88 | ||

| >2 months | 47 | 73.44 | ||

| Missing | 1 | 1.55 | ||

| Questions (0–10 Scale; 0 = Strongly Disagree, 10 = Strongly Agree) | All (n = 113) Mean (n) Standard Deviation = SD | Patients with SmPC-Compliant Application (n = 35) Mean (n) Standard Deviation = SD | Patients with Smpc Non-Compliant Application (N = 53) Mean (n) Standard Deviation = SD | p-Value (t-Test) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain “drug application” | felt sufficiently informed | 6.5 (106) SD = 2.82 Missing = 7 | 6.97 (35) SD = 2.61 | 6.11 (50) SD = 3.15 | 0.19 |

| informed about side effects | 5.76 (108) SD = 3.31 Missing = 5 | 6.34 (35) SD = 2.92 | 5.2 (50) SD = 3.78 | 0.14 | |

| informed about frequency of application | 7.32 (99) SD = 2.62 Missing = 14 | 7.14 (29) SD = 2.33 | 7.5 (50) SD = 2.75 | 0.54 | |

| informed about the maximal area that could be treated | 6.73 (100) SD = 2.95 Missing = 13 | 6.76 (29) SD = 2.65 | 6.87 (50) SD = 3.05 | 0.86 | |

| informed about application time | 6.56 (101) SD = 2.97 Missing = 12 | 7.42 (30) SD = 2.38 | 5.91 (50) SD = 3.32 | 0.02 | |

| informed about duration of therapy | 6.56 (102) SD = 2.91 Missing = 11 | 7.18 (31) SD = 2.3 | 6.15 (50) SD = 3.36 | 0.14 | |

| adjusted duration independently of prescribing physician | 4.5 (97) SD = 3.56 Missing = 16 | 2.59 (29) SD = 3.05 | 5.53 (50) SD = 3.53 | <0.001 | |

| adjusted frequency independently of prescribing physician | 4.27 (97) SD = 3.5 Missing = 16 | 3.16 (29) SD = 3.31 | 5.16 (50) SD = 3.58 | 0.02 | |

| received family support for correct application | 4.62 (100) SD = 3.95 Missing = 13 | 4.72 (30) SD = 3.5 | 4.93 (50) SD = 4.23 | 0.81 | |

| experienced strong side effects | 2.72 (97) SD = 3.12 Missing = 16 | 2.35 (29) SD = 2.6 | 2.67 (50) SD = 3.21 | 0.64 | |

| scared of side effects | 2.1 (100) SD = 2.65 Missing = 13 | 1.97 (30) SD = 2 | 2.14 (50) SD = 2.78 | 0.76 | |

| discontinuation of treatment due to side effects | 2.07 (85) SD = 3.23 Missing = 28 | 0.96 (24) SD = 2.19 | 2.35 (44) SD = 3.5 | 0.08 | |

| Domain “improvement of treatment education” | training before therapy | 3.77 (104) SD = 3.49 Missing = 9 | 2.94 (33) SD = 3.26 | 4.3 (52) SD = 3.51 | 0.06 |

| training video | 3.67 (102) SD = 3.6 Missing = 11 | 3.47 (31) SD = 3.3 | 3.72 (51) SD = 3.7 | 0.78 | |

| reminder application (APP, mobile phone) | 1.97 (102) SD = 2.88 Missing = 11 | 1.69 (32) SD = 2.47 | 2.27 (51) SD = 3.14 | 0.37 | |

| treatment diary | 2.12 (102) SD = 2.79 Missing = 11 | 2.31 (31) SD = 3.28 | 1.96 (52) SD = 2.36 | 0.58 | |

| application information online | 2.32 (102) SD = 2.97 Missing = 11 | 2.3 (32) SD = 3.26 | 2.25 (51) SD = 2.85 | 0.91 | |

| written application information | 4.75 (103) SD = 3.7 Missing = 10 | 4.14 (33) SD = 3.6 | 4.9 (50) SD = 3.83 | 0.38 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koch, E.A.T.; Steeb, T.; Bender-Säbelkampf, S.; Busch, D.; Feustel, J.; Kaufmann, M.D.; Maronna, A.; Meder, C.; Ronicke, M.; Toussaint, F.; et al. Poor Adherence to Self-Applied Topical Drug Treatment Is a Common Source of Low Lesion Clearance in Patients with Actinic Keratosis—A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3813. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12113813

Koch EAT, Steeb T, Bender-Säbelkampf S, Busch D, Feustel J, Kaufmann MD, Maronna A, Meder C, Ronicke M, Toussaint F, et al. Poor Adherence to Self-Applied Topical Drug Treatment Is a Common Source of Low Lesion Clearance in Patients with Actinic Keratosis—A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(11):3813. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12113813

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoch, Elias A. T., Theresa Steeb, Sophia Bender-Säbelkampf, Dorothee Busch, Janina Feustel, Matthias D. Kaufmann, Andreas Maronna, Christine Meder, Moritz Ronicke, Frédéric Toussaint, and et al. 2023. "Poor Adherence to Self-Applied Topical Drug Treatment Is a Common Source of Low Lesion Clearance in Patients with Actinic Keratosis—A Cross-Sectional Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 11: 3813. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12113813

APA StyleKoch, E. A. T., Steeb, T., Bender-Säbelkampf, S., Busch, D., Feustel, J., Kaufmann, M. D., Maronna, A., Meder, C., Ronicke, M., Toussaint, F., Wellein, H., Berking, C., & Heppt, M. V. (2023). Poor Adherence to Self-Applied Topical Drug Treatment Is a Common Source of Low Lesion Clearance in Patients with Actinic Keratosis—A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(11), 3813. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12113813