Serum Leucine-Rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein in Quiescent Crohn’s Disease as a Potential Surrogate Marker for Small-Bowel Ulceration detected by Capsule Endoscopy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

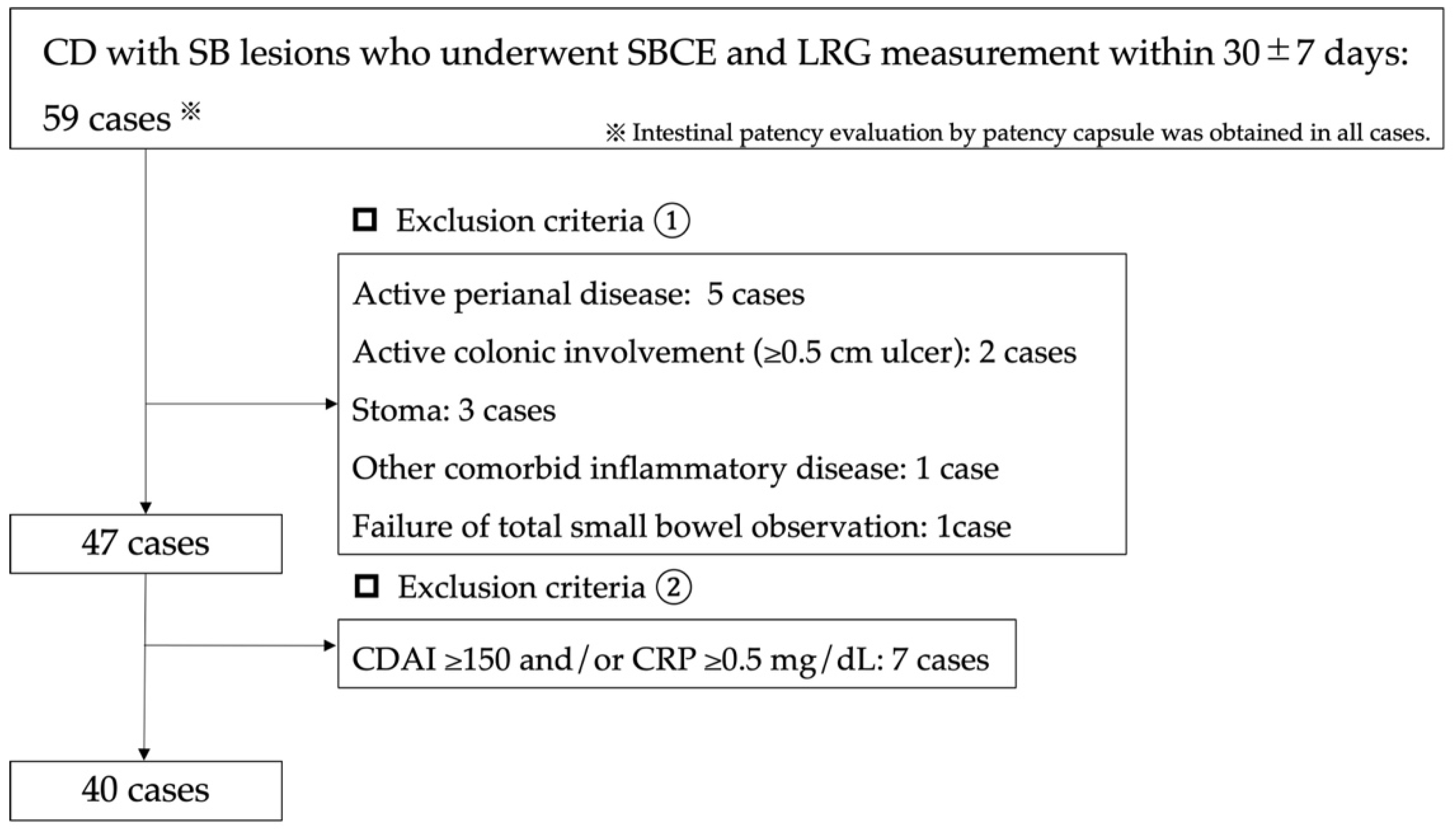

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients Selection

2.2. Evaluation Method

2.3. SBCE Procedure

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Summary of Capsule Endoscopy Findings

3.3. Evaluation Using LRG for Small-Bowel Ulcerative Lesions

3.4. Evaluation Using LRG for Lewis Scores ≥ 350

3.5. Comparison of Patients with LRG Values

3.6. The Correlations between SBCE Score and the LRG Values

3.7. Influence of Biologics on LRG Values and SBCE Scores

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schwartz, D.A.; Loftus, E.; Tremaine, W.J.; Panaccione, R.; Harmsen, W.; Zinsmeister, A.R.; Sandborn, W.J. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology 2002, 122, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gower, C.; Sarter, H.; Savoye, G.; Tavernier, N.; Fumery, M.; Sandborn, W.J.; Feagan, B.G.; Duhamel, A.; Guillon-Dellac, N.; Colombel, J.-F.; et al. Validation of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Disability Index in a population-based cohort. Gut 2015, 66, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenaka, K.; Ohtsuka, K.; Kitazume, Y.; Matsuoka, K.; Nagahori, M.; Fujii, T.; Saito, E.; Kimura, M.; Fujioka, T.; Watanabe, M. Utility of Magnetic Resonance Enterography For Small Bowel Endoscopic Healing in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturm, A.; Maaser, C.; Calabrese, E.; Annese, V.; Fiorino, G.; Kucharzik, T.; Vavricka, S.R.; Verstockt, B.; Van Rheenen, P.; Tolan, D.; et al. ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 2: IBD scores and general principles and technical aspects. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2018, 13, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, S.; Bruining, D.H.; Loftus, E.V.; Becker, B.; Fletcher, J.G.; Mandrekar, J.N.; Zinsmeister, A.R.; Sandborn, W.J. Endoscopic Skipping of the Distal Terminal Ileum in Crohn’s Disease Can Lead to Negative Results From Ileocolonoscopy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenaka, K.; Ohtsuka, K.; Kitazume, Y.; Nagahori, M.; Fujii, T.; Saito, E.; Fujioka, T.; Matsuoka, K.; Naganuma, M.; Watanabe, M. Correlation of the Endoscopic and Magnetic Resonance Scoring Systems in the Deep Small Intestine in Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 1832–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serada, S.; Fujimoto, M.; Terabe, F.; Iijima, H.; Shinzaki, S.; Matsuzaki, S.; Ohkawara, T.; Nezu, R.; Nakajima, S.; Kobayashi, T.; et al. Serum leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein is a disease activity biomarker in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 2169–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinzaki, S.; Matsuoka, K.; Iijima, H.; Mizuno, S.; Serada, S.; Fujimoto, M.; Arai, N.; Koyama, N.; Morii, E.; Watanabe, M.; et al. Leucine-rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein is a Serum Biomarker of Mucosal Healing in Ulcerative Colitis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2017, 11, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yasutomi, E.; Inokuchi, T.; Hiraoka, S.; Takei, K.; Igawa, S.; Yamamoto, S.; Ohmori, M.; Oka, S.; Yamasaki, Y.; Kinugasa, H.; et al. Leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein as a marker of mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serada, S.; Fujimoto, M.; Ogata, A.; Terabe, F.; Hirano, T.; Iijima, H.; Shinzaki, S.; Nishikawa, T.; Ohkawara, T.; Iwahori, K.; et al. iTRAQ-based proteomic identification of leucine-rich α-2 glycoprotein as a novel inflammatory biomarker in autoimmune diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 770–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeire, S.; Ferrante, M.; Rutgeerts, P. Recent advances: Personalised use of current Crohn’s disease therapeutic options. Gut 2013, 62, 1511–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yamamoto, H.; Ogata, H.; Matsumoto, T.; Ohmiya, N.; Ohtsuka, K.; Watanabe, K.; Yano, T.; Matsui, T.; Higuchi, K.; Nakamura, T.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for Enteroscopy. Dig. Endosc. 2017, 29, 519–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ben-Horin, S.; Lahat, A.; Amitai, M.M.; Klang, E.; Yablecovitch, D.; Neuman, S.; Levhar, N.; Selinger, L.; Rozendorn, N.; Turner, D.; et al. Assessment of small bowel mucosal healing by video capsule endoscopy for the prediction of short-term and long-term risk of Crohn’s disease flare: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, A.; Takenaka, K.; Hibiya, S.; Ohtsuka, K.; Okamoto, R.; Watanabe, M. Serum Leucine-Rich α2 Glycoprotein: A Novel Biomarker For Small Bowel Mucosal Activity in Crohn’s Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 20, e1196–e1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leenhardt, R.; Buisson, A.; Bourreille, A.; Marteau, P.; Koulaouzidis, A.; Li, C.; Keuchel, M.; Rondonotti, E.; Toth, E.; Plevris, J.N.; et al. Nomenclature and semantic descriptions of ulcerative and inflammatory lesions seen in Crohn’s disease in small bowel capsule endoscopy: An international Delphi consensus statement. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2020, 8, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leenhardt, R.; Koulaouzidis, A.; McNamara, D.; Keuchel, M.; Sidhu, R.; McAlindon, M.; Saurin, J.; Eliakim, R.; Sainz, I.F.-U.; Plevris, J.; et al. A guide for assessing the clinical relevance of findings in small bowel capsule endoscopy: Analysis of 8064 answers of international experts to an illustrated script questionnaire. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2021, 45, 101637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omori, T.; Matsumoto, T.; Hara, T.; Kambayashi, H.; Murasugi, S.; Ito, A.; Yonezawa, M.; Nakamura, S.; Tokushige, K. A Novel Capsule Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease. Crohn’s Colitis 360 2020, 2, otaa040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.-H.; Yang, S.-K.; Park, S.H.; Lee, H.-S.; Boo, S.-J.; Park, J.-H.; Na, S.Y.; Jung, K.W.; Kim, K.-J.; Ye, B.D.; et al. Usefulness of C-Reactive Protein as a Disease Activity Marker in Crohn’s Disease according to the Location of Disease. Gut Liver 2015, 9, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lewis, J.D.; Rutgeerts, P.; Feagan, B.G.; D’Haens, G.; Danese, S.; Colombel, J.-F.; Reinisch, W.; Rubin, D.T.; Selinger, C.; Bewtra, M.; et al. Correlation of Stool Frequency and Abdominal Pain Measures with Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopylov, U.; Yablecovitch, D.; Lahat, A.; Neuman, S.; Levhar, N.; Greener, T.; Klang, E.; Rozendorn, N.; Amitai, M.M.; Ben-Horin, S.; et al. Detection of Small Bowel Mucosal Healing and Deep Remission in Patients with Known Small Bowel Crohn’s Disease Using Biomarkers, Capsule Endoscopy, and Imaging. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 1316–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n = 40 (%), Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|

| Males | 28 (70) |

| Age, years | 36.4 (32–50.6) |

| Disease duration, years | 12.8 (7.2–17.6) |

| Montreal classification: | |

| A1/A2/A3 | 5 (12.5)/30 (75)/5 (12.5) |

| B1/B2/B3 | 18 (45)/12 (30)/10 (25) |

| L1/L2/L3 | 13 (32.5)/0 (0)/27 (67.5) |

| Evaluation for L3 by colonoscopy within 2 months of their SBCE, n, days | 8 (29.6), 20.5 (4.8–35.8) |

| Active colonic involvement | 0 (0) |

| Perianal disease | 10 (25) |

| Active perianal disease involvement | 0 (0) |

| Past intestinal surgery | 20 (50) |

| Smoking non/current/past | 26 (65)/9 (22.5)/5 (12.5) |

| Medication | |

| 5ASA | 33 (82.5) |

| Elemental diet | 19 (47.5) |

| PSL | 1 (2.5) |

| AZA | 8 (20) |

| Anti-TNFα inhibitor | 20 (50) |

| IL-12/23p40 inhibitor | 4 (10) |

| Integrin inhibitor | 1 (2.5) |

| WBC/μL | 5800 (4620–7488) |

| Hb, g/dL | 13.7 (12.2–14.7) |

| Ht, % | 40.7 (37–44) |

| Plt × 104/μL | 24.6 (21.1–29.2) |

| Alb, g/dL | 4.4 (4.2–4.7) |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.08 (0.05–0.15) |

| LRG, μg/mL | 12.3 (8.9–14.1) |

| CDAI | 67 (29.5–89.8) |

| Interval between SBCE and CDAI/biomarker evaluation, days | 6 (0–11) |

| Total n = 40 | ||

|---|---|---|

| SBCE score | Lewis score | 0 (0–192) |

| CECDAI | 3 (0–6) | |

| CDACE | 211 (0–420) | |

| SB Ulcer ≥ 0.5 cm (%) | 11 (27.5) | |

| Lewis score ≥ 350 (%) | 5 (12.5) | |

| Inflammation on 1st and/or 2nd tertile in Lewis score (%) | 7 (17.5) | |

| Lewis score < 135, ≥135–<790, ≥790 (%) | 26 (65)/10 (25)/4 (10) | |

| No inflammation (Lewis score = 0) (%) | 25 (62.5) | |

| Passable stenosis (%) | 6 (15) | |

| Total | LRG ≥ 14 μg/mL | LRG < 14 μg/mL | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 40 | n = 12 | n = 28 | |||

| SBCE score | Lewis score | 0 (0–192) | 268 (45–3272) | 0 (0–0) | 0.0002 |

| CECDAI | 3 (0–6) | 7.5 (3.5–12) | 3 (0–5.8) | 0.0027 | |

| CDACE | 211 (0–420) | 421 (312–913) | 210 (0–310) | 0.0031 | |

| Presence of small-bowel ulcer, ≥0.5 cm (%) | 11 (27.5) | 7(58.3) | 4 (14.3) | 0.0078 | |

| Lewis score ≥ 350 (%) | 5 (12.5) | 5 (41.7) | 0 (0) | 0.0012 | |

| Biomarkers/clinical activity: | |||||

| Hb, g/dL | 13.7 (12.2–14.7) | 14.2 (12.7–14.7) | 13.6 (12.1–15) | 0.4339 | |

| Plt × 104/μL | 24.6 (21.1–29.2) | 24.9 (23.7–30) | 23.6 (21–29) | 0.2747 | |

| Alb, g/dL | 4.4 (4.2–4.7) | 4.3 (4.1–4.4) | 4.5 (4.2–4.8) | 0.0218 | |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.08 (0.05–0.15) | 0.12 (0.08–0.33) | 0.08 (0.05–0.11) | 0.0275 | |

| LRG, μg/mL | 12.3 (8.9–14.1) | 15 (14.2–16.7) | 10.3 (9.2–12.9) | <0.0001 | |

| CDAI | 67 (29.5–89.8) | 83.5 (63.5–109) | 64 (28–86) | 0.0550 | |

| Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient (ρ) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| vs. LRG | ||

| CRP | 0.3707 | 0.0186 |

| CDAI | 0.4768 | 0.0019 |

| Lewis score | 0.5832 | <0.0001 |

| CECDAI | 0.5985 | <0.0001 |

| CDACE | 0.5495 | 0.0002 |

| vs. CRP | ||

| CDAI | 0.0693 | 0.6710 |

| Lewis score | 0.1540 | 0.3428 |

| CECDAI | 0.2139 | 0.1851 |

| CDACE | 0.2074 | 0.1991 |

| vs. CDAI | ||

| Lewis Score | 0.1363 | 0.4017 |

| CECDAI | 0.3116 | 0.0503 |

| CDACE | 0.2179 | 0.1767 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Omori, T.; Sasaki, Y.; Koroku, M.; Murasugi, S.; Yonezawa, M.; Nakamura, S.; Tokushige, K. Serum Leucine-Rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein in Quiescent Crohn’s Disease as a Potential Surrogate Marker for Small-Bowel Ulceration detected by Capsule Endoscopy. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2494. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11092494

Omori T, Sasaki Y, Koroku M, Murasugi S, Yonezawa M, Nakamura S, Tokushige K. Serum Leucine-Rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein in Quiescent Crohn’s Disease as a Potential Surrogate Marker for Small-Bowel Ulceration detected by Capsule Endoscopy. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(9):2494. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11092494

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmori, Teppei, Yu Sasaki, Miki Koroku, Shun Murasugi, Maria Yonezawa, Shinichi Nakamura, and Katsutoshi Tokushige. 2022. "Serum Leucine-Rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein in Quiescent Crohn’s Disease as a Potential Surrogate Marker for Small-Bowel Ulceration detected by Capsule Endoscopy" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 9: 2494. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11092494

APA StyleOmori, T., Sasaki, Y., Koroku, M., Murasugi, S., Yonezawa, M., Nakamura, S., & Tokushige, K. (2022). Serum Leucine-Rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein in Quiescent Crohn’s Disease as a Potential Surrogate Marker for Small-Bowel Ulceration detected by Capsule Endoscopy. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(9), 2494. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11092494