Comparing Differences between Two Groups of Adolescents Hospitalized for Self-Harming Behaviors with and without Personality Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

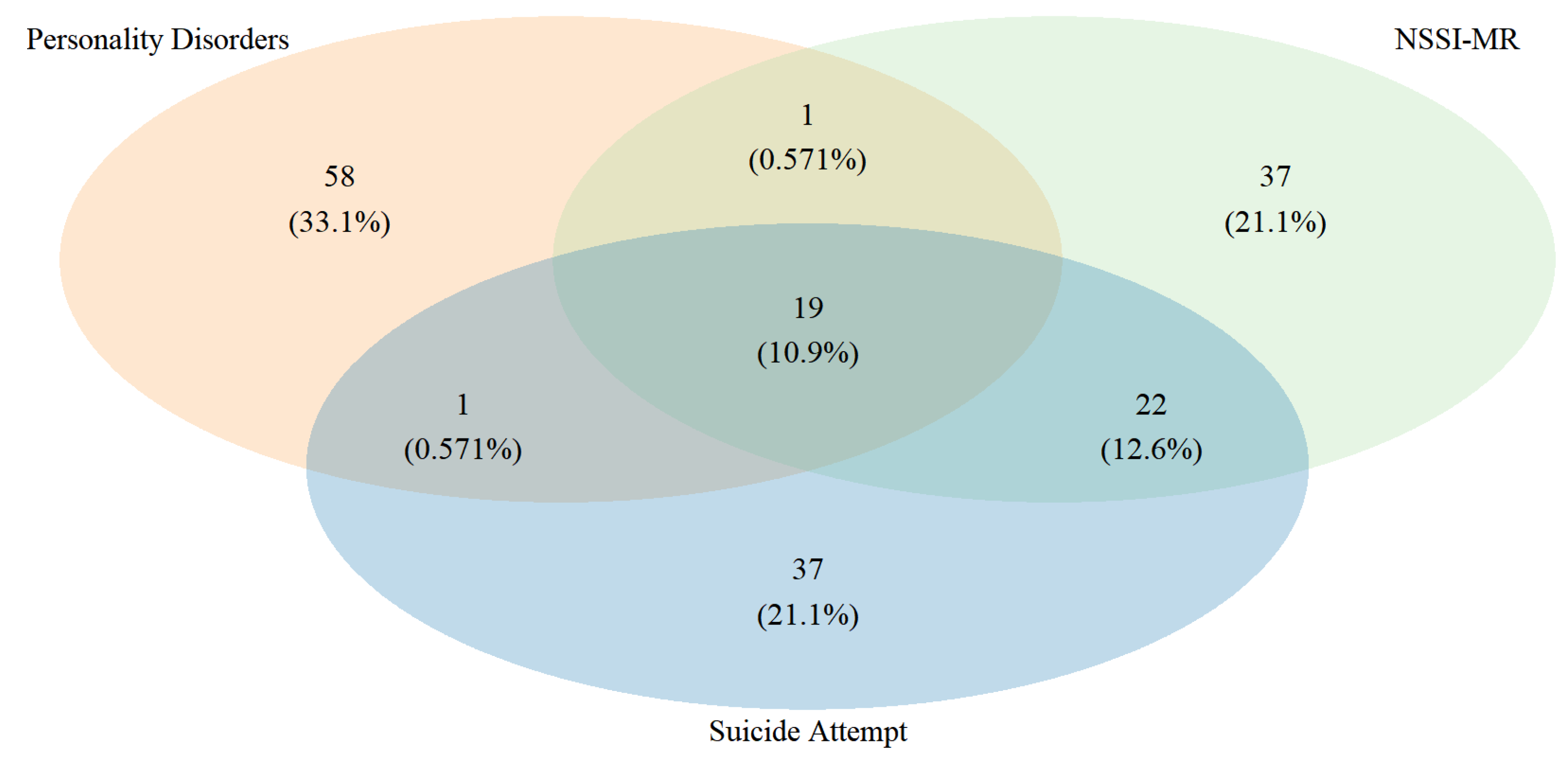

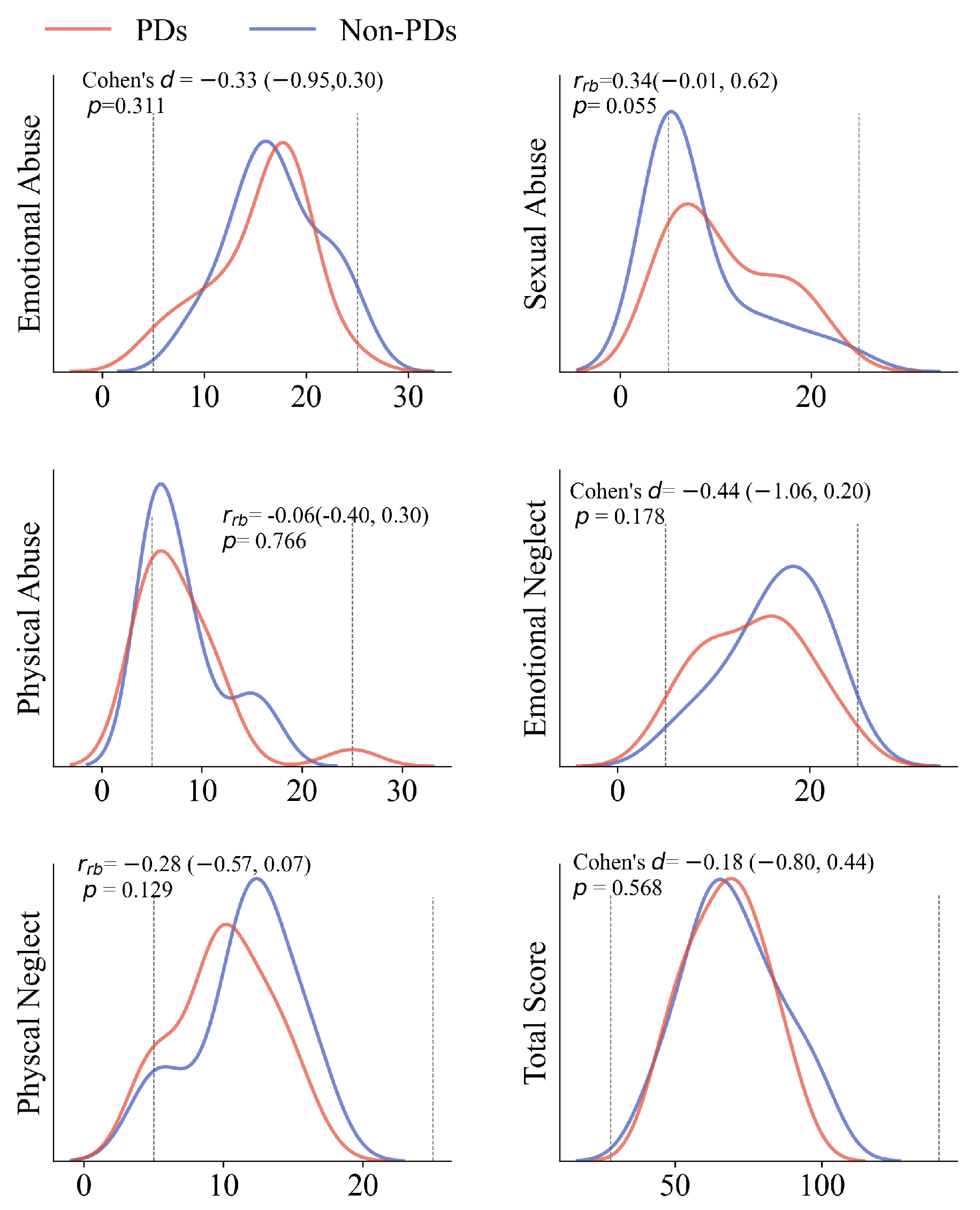

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

| APRI-V | The Adolescent Peer Relations Instrument-Victimization |

| ASPD | Antisocial personality disorder |

| BPD | Borderline personality disorder |

| CD | Conduct disorder |

| CTQ-SF | The Child Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form |

| DSM-5 | The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition |

| NSSI | Non-suicidal self-injury |

| NSSI-MR | Non-suicidal self-injury Major Repeater |

| PDs | Personality disorders |

| SA | Suicide attempt |

| SB | Suicidal behavior |

| SITBI | The Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Questionnaire |

| PSS | The Paykel Suicide Scale |

| UP3 | The Unbearable Psychache Scale |

References

- Oumaya, M.; Friedman, S.; Pham, A.; Abou Abdallah, T.; Guelfi, J.D.; Rouillon, F. Borderline personality disorder, self-mutilation and suicide: Literature review. L’Encephale 2008, 34, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawton, K.; Saunders, K.E.A.; O’Connor, R.C. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet 2012, 379, 2373–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, B.J.; Jones, R.M.; Hare, T.A. The adolescent brain. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1124, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A.L.; Neft, D.; Golombeck, N. Borderline personality disorder and adolescence. Soc. Work. Ment. Health 2008, 6, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenssen, E.M.P.; Hutsebaut, J.; Feenstra, D.J.; Van Busschbach, J.J.; Luyten, P. Diagnosis of personality disorders in adolescents: A study among psychologists. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2013, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, R.; Steppan, M.; Zimmermann, J.; Oeltjen, L.; Birkhölzer, M.; Schmeck, K.; Goth, K. A DSM-5 AMPD and ICD-11 compatible measure for an early identification of personality disorders in adolescence-LoPF-Q 12–18 latent structure and short form. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fruyt, F.; De Clercq, B. Antecedents of personality disorder in childhood and adolescence: Toward an integrative developmental model. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 10, 449–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgeland, M.I.; Kjelsberg, E.; Torgersen, S. Continuities between emotional and disruptive behavior disorders in adolescence and personality disorders in adulthood. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 1941–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiner, R.L. The development of personality disorders: Perspectives from normal personality development in childhood and adolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 2009, 21, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moselli, M.; Casini, M.P.; Frattini, C.; Williams, R. Suicidality and Personality Pathology in Adolescence: A Systematic Review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenström, T.; Torvik, F.A.; Ystrom, E.; Czajkowski, N.O.; Gillespie, N.A.; Aggen, S.H.; Krueger, R.F.; Kendler, K.S.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T. Prediction of alcohol use disorder using personality disorder traits: A twin study. Addiction 2018, 113, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Luo, T.; Liu, L.; Dong, H.; Hao, W. Prevalence Rates of Personality Disorder and Its Association With Methamphetamine Dependence in Compulsory Treatment Facilities in China. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichl, C.; Kaess, M. Self-harm in the context of borderline personality disorder. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 37, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, B.J.; Dixon-Gordon, K.L.; Austin, S.B.; Rodriguez, M.A.; Zachary Rosenthal, M.; Chapman, A.L. Non-suicidal self-injury with and without borderline personality disorder: Differences in self-injury and diagnostic comorbidity. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 230, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, P. Child development and personality disorder. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 31, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, B.W.; Walton, K.E.; Viechtbauer, W. Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Nieto, R.; Blasco-Fontecilla, H.; Yepes, M.P.; Baca-García, E. Traducción y validación de la Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview en población espa nola con conducta suicida. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2013, 6, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Inchausti, F.; Pérez-Albéniz, A.; Ortuño-Sierra, J. Validation of the Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief in a representative sample of adolescents: Internal structure, norms, reliability, and links with psychopathology. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 27, e1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachkowski, M.C.; May, A.M.; Tsai, M.; Klonsky, E.D. A brief measure of unbearable psychache. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2019, 49, 1721–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.P.; Stein, J.A.; Newcomb, M.D.; Walker, E.; Pogge, D.; Ahluvalia, T.; Stokes, J.; Handelsman, L.; Medrano, M.; Desmond, D.; et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abus. Negl. 2003, 27, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascón-Cánovas, J.J.; de Leon, J.R.R.; Fernandez, A.C.; Calzado, J.M.H. Adaptación cultural al espa nol y baremación del Adolescent Peer Relations Instrument (APRI) para la detección de la victimización por acoso escolar: Estudio preliminar de las propiedades psicométricas. An. Pediatr. 2017, 87, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, A.; Gallardo-Pujol, D.; Pereda, N.; Arntz, A.; Bernstein, D.P.; Gaviria, A.M.; Labad, A.; Valero, J.; Gutiérrez-Zotes, J.A. Initial validation of the Spanish childhood trauma questionnaire-short form: Factor structure, reliability and association with parenting. J. Interpers. Violence 2013, 28, 1498–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasco-Fontecilla, H.; Fernández-Fernández, R.; Colino, L.; Fajardo, L.; Perteguer-Barrio, R.; de Leon, J. The Addictive Model of Self-Harming (Non-suicidal and Suicidal) Behavior. Front. Psychiatry 2016, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ayodeji, E.; Green, J.; Roberts, C.; Trainor, G.; Rothwell, J.; Woodham, A.; Wood, A. The influence of personality disorder on outcome in adolescent self-harm. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2015, 207, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.P.; Cohen, P.; Velez, C.N.; Schwab-Stone, M.; Siever, L.J.; Shinsato, L. Prevalence and stability of the DSM-III-R personality disorders in a community-based survey of adolescents. Am. J. Psychiatry 1993, 150, 1237–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.G.; Cohen, P.; Kasen, S.; Skodol, A.E.; Hamagami, F.; Brook, J.S. Age-related change in personality disorder trait levels between early adolescence and adulthood: A community-based longitudinal investigation. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2000, 102, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozzatello, P.; Garbarini, C.; Rocca, P.; Bellino, S. Borderline Personality Disorder: Risk Factors and Early Detection. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infurna, M.R.; Brunner, R.; Holz, B.; Parzer, P.; Giannone, F.; Reichl, C.; Fischer, G.; Resch, F.; Kaess, M. The Specific Role of Childhood Abuse, Parental Bonding, and Family Functioning in Female Adolescents with Borderline Personality Disorder. J. Personal. Disord. 2016, 30, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolke, D.; Schreier, A.; Zanarini, M.C.; Winsper, C. Bullied by peers in childhood and borderline personality symptoms at 11 years of age: A prospective study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2012, 53, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuja-Halkola, R.; Lind Juto, K.; Skoglund, C.; Rück, C.; Mataix-Cols, D.; Pérez-Vigil, A.; Larsson, J.; Hellner, C.; Långström, N.; Petrovic, P.; et al. Do borderline personality disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder co-aggregate in families? A population-based study of 2 million Swedes. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storebø, O.J.; Simonsen, E. The Association Between ADHD and Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD): A Review. J. Atten. Disord. 2016, 11, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, M.; Tomas, I.A.; Temes, C.M.; Fitzmaurice, G.M.; Aguirre, B.A.; Zanarini, M.C. Suicide attempts and self-injurious behaviours in adolescent and adult patients with borderline personality disorder. Personal. Ment. Health 2017, 11, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Total (n = 79) | PDs (n = 22) | Control (n = 57) | p-Value 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 14.70 ± 1.54 | 15.27 ± 1.16 | 14.47 ± 1.62 | 0.04 |

| Female | 70 (88.6%) | 19 (86.4%) | 51 (89.5%) | 0.70 |

| Ethnic | 0.54 | |||

| Caucasian | 62 (78.5%) | 16 (72.7%) | 46 (80.7%) | |

| Others | 16 (21.5%) | 6 (27.3%) | 11 (19.3%) | |

| Household Income | 0.39 | |||

| <1500 Euro/month | 15(18.99%) | 5 (22.73%) | 10 (17.50%) | |

| 1500–2500 Euro/month | 33 (41.78%) | 11 (50.00%) | 22 (38.60%) | |

| >2500 Euro/month | 31 (39.23%) | 6 (27.27%) | 25 (43.90%) | |

| Birth Order | 0.87 | |||

| Only Child | 8 (10.13%) | 2 (9.10%) | 6 (10.53%) | |

| Oldest Child | 32 (40.50%) | 10 (45.45%) | 22 (38.60%) | |

| Others | 39 (49.37%) | 10 (45.45%) | 29 (50.87%) | |

| Screen Time | ||||

| Social Media (hr.) | 3.57 ± 2.38 | 4.32 ± 2.5 | 3.28 ± 2.29 | 0.12 |

| Video Games (hr.) | 0.58 ± 1.05 | 0.50 ± 0.80 | 0.62 ± 1.15 | 0.68 |

| Substance use | ||||

| Alcohol | 28 (35.44%) | 9 (40.91%) | 19 (33.33%) | 0.71 |

| Tabacco | 23 (29.11%) | 8 (36.36%) | 15 (26.32%) | 0.55 |

| NSSI Onset 2 (n = 72) | 12.75 ± 2.32 | 12.90 ± 1.92 | 12.69 ± 2.48 | 0.96 |

| SA Onset 2 (n = 58) | 13.87 ± 1.93 | 14.00 ± 1.89 | 13.80 ± 1.97 | 0.71 |

| NSSI-MR 3 | 46 (58.23%) | 20 (90.91%) | 26 (45.61%) | <0.01 |

| SA | 2.72 ± 3.64 | 4.23 ± 4.38 | 2.14 ± 3.17 | <0.01 |

| PSS 4 | 4.63 ± 0.68 | 4.64 ± 0.90 | 4.63 ± 0.57 | 0.42 |

| UP3 4 | 11.97 ± 3.32 | 12.91 ± 3.1 | 11.55 ± 3.35 | 0.07 |

| SITBI 4 | 10.27 ± 2.85 | 10.27 ± 2.21 | 10.27 ± 3.11 | 0.99 |

| CTQ-SF 4 | 65.84 ± 13.90 | 69.45 ± 15.70 | 64.37 ± 12.97 | 0.15 |

| Emotional Abuse | 14.47 ± 5.30 | 15.73 ± 4.80 | 13.96 ± 5.45 | 0.19 |

| Physical Abuse | 7.38 ± 4.16 | 8.86 ± 5.54 | 6.78 ± 3.32 | 0.05 |

| Sexual Abuse | 8.30 ± 5.23 | 10.73 ± 5.79 | 7.31 ± 4.68 | <0.01 |

| Emotional Neglect | 16.17 ± 5.61 | 15.14 ± 5.75 | 16.59 ± 5.54 | 0.31 |

| Physcal Neglect | 10.93 ± 3.38 | 10.50 ± 3.36 | 11.11 ± 3.41 | 0.48 |

| APRI-V4 | 4.37 ± 5.51 | 5.23 ± 5.90 | 4.02 ± 5.36 | 0.49 |

| Social/Verbal Bullying | 3.37 ± 4.02 | 4.09 ± 4.48 | 3.07 ± 3.82 | 0.61 |

| Physical Bullying | 1.00 ± 1.73 | 1.14 ± 1.70 | 0.94 ± 1.75 | 0.30 |

| Clinical Diagnosis | ||||

| Major depressive disorder | 30 (37.97%) | 7 (31.8%) | 23 (40.4%) | 0.48 |

| Anxiety disorders | 6 (7.59%) | 1 (4.5%) | 5 (8.8%) | 0.87 |

| ADHD 5 | 23(29.11%) | 10 (45.5%) | 13 (22.8%) | 0.05 |

| Eating Disorders | 13 (16.46%) | 2 (9.1%) | 11 (19.3%) | 0.33 |

| Substance Use Disorders | 6 (7.59%) | 2 (9.1%) | 4 (7%) | 0.67 |

| Conduct Disorder | 27 (34.18%) | 11 (50%) | 16 (28.1%) | 0.07 |

| Other Emotional Disorders 5 | 39(49.37%) | 13 (59.1%) | 26 (45.6%) | 0.28 |

| Variables | Total (n = 41) | PDs (n = 19) | Non-PDs (n = 22) | p-Value 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 14.88 ± 1.54 | 15.32 ± 1.20 | 14.50 ± 1.71 | 0.11 |

| NSSI Onset 2 | 12.32 ± 2.42 | 12.68 ± 1.86 | 12.00 ± 2.83 | 0.37 |

| SA Onset 2 | 13.90 ± 1.97 | 14.11 ± 1.88 | 13.73 ± 2.07 | 0.55 |

| UP3 3 | 12.87 ± 2.41 | 12.30 ± 2.89 | 13.47 ± 1.65 | 0.17 |

| CTQ-SF 3 | 68.63 ± 14.78 | 67.21 ± 13.45 | 69.90 ± 16.10 | 0.57 |

| Emotional Abuse | 16.32 ± 4.67 | 17.05 ± 4.52 | 15.53 ± 4.81 | 0.31 |

| Physical Abuse | 8.08 ± 4.32 | 8.05 ± 4.82 | 8.10 ± 3.92 | 0.77 |

| Sexual Abuse | 9.60 ± 5.81 | 10.95 ± 5.70 | 8.38 ± 5.77 | 0.06 |

| Emotional Neglect | 15.38 ± 5.38 | 16.48 ± 5.17 | 14.16 ± 5.48 | 0.18 |

| Physcal Neglect | 10.90 ± 3.56 | 10.11 ± 3.41 | 11.62 ± 3.61 | 0.13 |

| APRI-V 3 | 4.37 ± 5.51 | 5.23 ± 5.90 | 4.02 ± 5.36 | 0.49 |

| Social/Verbal Bullying | 3.97 ± 4.29 | 3.84 ± 4.35 | 4.10 ± 4.35 | 0.62 |

| Physical Bullying | 1.00 ± 1.54 | 0.84 ± 1.17 | 1.14 ± 1.82 | 0.87 |

| Clinical Diagnosis | ||||

| Major depressive disorder | 18 (43.90%) | 7 (36.84%) | 11 (50.00%) | 0.53 |

| Anxiety disorders | 2 (4.88%) | 1 (5.26%) | 1 (4.55%) | 0.99 |

| ADHD 4 | 14 (34.15%) | 8 (42.10%) | 6 (27.27%) | 0.35 |

| Eating Disorders | 7 (17.07%) | 2 (10.53%) | 5 (22.73%) | 0.42 |

| Substance Use Disorders | 4 (9.76%) | 2 (10.53%) | 2 (9.09%) | 0.99 |

| Conduct Disorder | 14 (34.15%) | 9 (47.37%) | 5 (22.73%) | 0.11 |

| Other Emotional Disorders 4 | 21 (51.22%) | 10 (52.63%) | 11 (50.00%) | 0.99 |

| Age | NSSI-MR 1 | Conduct Disorder | Sexual Abuse 2 | ADHD 3 | Physical Abuse 4 | UP3 5 | Suicide Attempts | AIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cru.OR (95% CI) | 1.45 (1.00–2.10) | 11.3 (2.38–53.69) | 2.27 (0.81–6.37) | 4.03 (1.38–11.79) | 2.88 (0.98–8.43) | 1.89 (0.69–5.24) | 1.16 (0.96–1.4) | 4.00 (0.82–19.42) | |

| Model 1 | 77.30 | ||||||||

| b (SE) | 0.56 (0.24) * | 2.67 (0.95) ** | 1.25 (0.75) | 0.82 (0.73) | 0.86 (0.68) | −0.33 (0.69) | 0.03 (0.13) | 0.18 (1.10) | |

| Adj.OR (95% CI) | 1.75 (1.08–2.83) | 14.48 (2.24–93.67) | 3.49 (0.80–15.21) | 2.27 (0.55–9.48) | 2.36 (0.61–9.10) | 0.71 (0.18–2.77) | 1.03 (0.79–1.35) | 1.20 (0.14–10.36) | |

| Model 2 | 73.40 | ||||||||

| b (SE) | 0.54 (0.23) * | 2.74 (0.89) ** | 1.29 (0.75) | 1.01 (0.68) | 0.86 (0.67) | −0.37 (0.68) | - | - | |

| Adj.OR (95% CI) | 1.72 (1.09–2.73) | 15.43 (2.71–87.93) | 3.65 (0.85–15.72) | 2.75 (0.72–10.51) | 2.36 (0.63–8.85) | 0.69 (0.18–2.63) | - | - | |

| Model 3 | 71.63 | ||||||||

| b (SE) | 0.52 (0.23) * | 2.64 (0.86) ** | 1.29 (0.74) | 0.97 (0.68) | 0.80 (0.66) | - | - | - | |

| Adj.OR (95% CI) | 1.69 (1.08–2.64) | 13.94 (2.57–75.62) | 3.62 (0.84–15.49) | 2.63 (0.70–9.95) | 2.23 (0.61-8.16) | - | - | - | |

| Model 4 | 70.99 | ||||||||

| b (SE) | 0.51 (0.23) * | 2.66 (0.85) ** | 1.32 (0.73) | 1.02 (0.66) | - | - | - | - | |

| Adj.OR (95% CI) | 1.67 (1.07–2.61) | 14.33 (2.70–76.14) | 3.75 (0.90–15.64) | 2.77 (0.76–10.18) | - | - | - | - | |

| Model 5 | 70.85 | ||||||||

| b (SE) | 0.50 (0.22) * | 2.69(0.84) ** | 1.71 (0.69) * | - | - | - | - | ||

| Adj.OR (95% CI) | 1.65 (1.08–2.53) | 14.84 (2.88–76.45) | 5.55 (1.45–21.28) | - | - | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, P.; Li, C.; Bella-Fernández, M.; Martin-Moratinos, M.; Castaño, L.M.; del Sol-Calderón, P.; Díaz de Neira, M.; Blasco-Fontecilla, H. Comparing Differences between Two Groups of Adolescents Hospitalized for Self-Harming Behaviors with and without Personality Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7263. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11247263

Wang P, Li C, Bella-Fernández M, Martin-Moratinos M, Castaño LM, del Sol-Calderón P, Díaz de Neira M, Blasco-Fontecilla H. Comparing Differences between Two Groups of Adolescents Hospitalized for Self-Harming Behaviors with and without Personality Disorders. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(24):7263. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11247263

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Ping, Chao Li, Marcos Bella-Fernández, Marina Martin-Moratinos, Leticia Mallol Castaño, Pablo del Sol-Calderón, Mónica Díaz de Neira, and Hilario Blasco-Fontecilla. 2022. "Comparing Differences between Two Groups of Adolescents Hospitalized for Self-Harming Behaviors with and without Personality Disorders" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 24: 7263. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11247263

APA StyleWang, P., Li, C., Bella-Fernández, M., Martin-Moratinos, M., Castaño, L. M., del Sol-Calderón, P., Díaz de Neira, M., & Blasco-Fontecilla, H. (2022). Comparing Differences between Two Groups of Adolescents Hospitalized for Self-Harming Behaviors with and without Personality Disorders. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(24), 7263. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11247263