Abstract

Mitochondria are important organelles whose primary role is generating energy through the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system. Cardiomyopathy, a common clinical disorder, is frequently associated with pathogenic mutations in nuclear and mitochondrial genes. To date, a growing number of nuclear gene mutations have been linked with cardiomyopathy; however, knowledge about mitochondrial tRNAs (mt-tRNAs) mutations in this disease remain inadequately understood. In fact, defects in mt-tRNA metabolism caused by pathogenic mutations may influence the functioning of the OXPHOS complexes, thereby impairing mitochondrial translation, which plays a critical role in the predisposition of this disease. In this review, we summarize some basic knowledge about tRNA biology, including its structure and function relations, modification, CCA-addition, and tRNA import into mitochondria. Furthermore, a variety of molecular mechanisms underlying tRNA mutations that cause mitochondrial dysfunctions are also discussed in this article.

1. Introduction

The term “cardiomyopathy” refers to a condition in which the heart muscle is abnormal in thickness, stiffness, or strength. There are several types of cardiomyopathy, named dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM), and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) [1,2]. Among them, DCM is the leading cause of heart failure (HF) [3], while HCM is a frequent genetic disease associated with nuclear or mitochondrial gene mutations. RCM is a mix of diseases featured by stiffness of the ventricular walls, which finally leads to HF [1]. ARVC is a pathological condition linked to the replacement of cardiac with fibrofatty tissues, which results in reduced cardiac functions and increases the risk of sudden cardiac death [1]. In fact, primary cardiomyopathy can be genetic, acquired, or mixed in etiology [4]. In particular, genetic cardiomyopathies are caused by chromosomal abnormalities that affect the heart [5]. Despite the fact that the etiology for these cardiomyopathies is different, there is an obvious inherited factor that contributes to the progression of this disease. It is well-recognized that autosomal recessive, X-linked, and matrilineal inheritance are the main patterns for cardiomyopathy [6,7]. Because mtDNA generates more than 90% of ATP, which is essential for normal heart functions [8], defects in mitochondrial function have been regarded as an important contributor to cardiomyopathy [9].

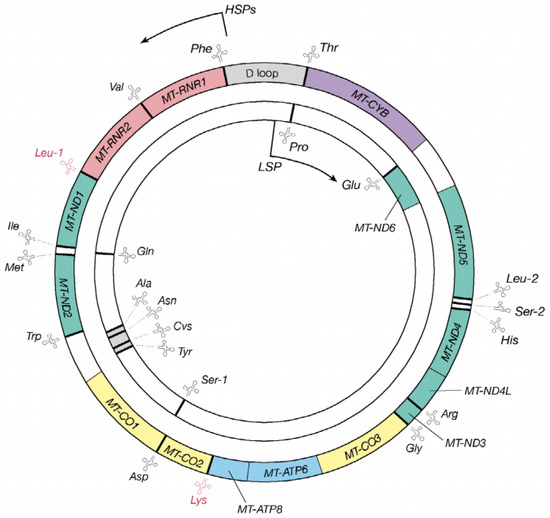

Human mitochondria are membrane-bound cell organelles that play important roles in regulating programmed cell death or necrosis, affecting cellular proliferation and metabolism, and promoting cholesterol synthesis [10]. However, the most important function of these organelles is to generate ATP via OXPHOS and release reactive oxygen species (ROS) as a toxic byproduct [11]. In fact, as shown in Figure 1, human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is a relatively small (16,569-bp), double-strand molecule that contains 13 genes for peptides for mitochondrial respiratory chain (MRC), two for mitochondrial rRNAs (12S rRNA and 16S rRNA) and 22 for mt-tRNA [12]. To date, more than 200 pathogenic mtDNA mutations have been mapped into mt-tRNA genes (http://www.mitomap.org/MITOMAP, accessed on 15 August 2022) [13], emphasizing the importance of mt-tRNAs for mitochondrial function [14]. In the current review, we provide an overview of the recent progress on human mt-tRNAs and discuss the potential mechanisms underlying cardiomyopathy-associated mt-tRNA mutations.

Figure 1.

The genetic map of the human mitochondrial genome, which is 16,569-bp. The outer circle presents the heavy strand, while the inner circle indicates the light strand and 22 genes encoding mt-tRNA molecules are distributed throughout the mtDNA genome.

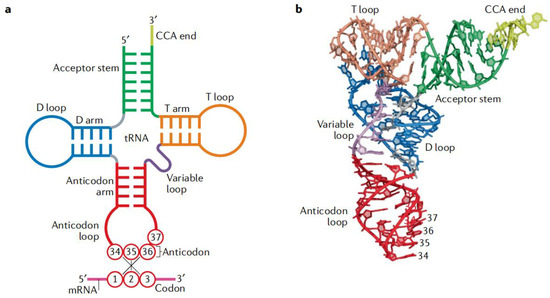

2. mt-tRNA Genes and Structure

As the adaptor that decodes the mRNA sequence into protein, the basic aspects of mt-tRNA structure and function are central to all studies of mitochondrial biomedicine. Almost every mt-tRNA has a cloverleaf structure consisting of an Acceptor arm, D-arm, anticodon stem, Variable region, and TψC loop, with an average length of approximately 73-bp [15]. Of 22 mt-tRNAs, MT-TE, MT-TA, MT-TN, MT-TC, MT-TY, MT-TS1, MT-TQ, and MT-TP occur at the L-strand, the rest, MT-TF, MT-TV, MT-TL1, MT-TL2, MT-TI, MT-TM, MT-TS2, MT-TW, MT-TD, MT-TK, MT-TG, MT-TR, MT-TH, and MT-TT, are present in the H-strand [16]. Interestingly, the tRNA cloverleaf structure forms an interaction between the D-arm and the TΨC loop, while the anticodon stem, which spans the positions of 34 to 36 of the canonical tRNAs, is the place where the codon and anticodon interact [17] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Basic structure and function of tRNA. (a) Cloverleaf structure of tRNA with codon–anticodon pairing: the tRNA consists of five parts: Acceptor arm, D-arm, anticodon stem, Variable region, and TΨC loop. (b) Tertiary structure of tRNA: the coordinates are obtained from Protein Data Bank entry 1EHZ. The color code is the same as in part a.

Intriguingly, the secondary structure of the tRNASer(AGY) lacks the entire D-arm [18], which is common in various mammalian mitochondrial genes. Remarkably, human mt-tRNASer(UCN) has some special characteristics: only one base spanning the Acceptor arm and D-arm, as well as a shortened D-arm and an extra loop [19].

3. mt-tRNA 5′ and 3′ End Processing

mt-tRNAs require essential maturation steps to become functional. These maturations comprise endoribonucleolytic and/or trimming of 5′ and 3′ extensions, tRNA splicing, base modifications, base editing, and CCA addition that allows aminoacylation [20]. In particular, the RNase P, which was first identified in bacteria, is responsible for 5′ end maturation [21]. Human mitochondrial RNase P (mt-RNase P) consists of three protein sub-units: TRMT10C, SDR5C1, and PRORP, all of which are encoded by the nuclear DNA (nDNA) [22,23].

3′-end processing pathways, by contrast, are more diverse. This biochemical process is performed by the endonuclease RNase Z or the exonuclease Rex1p [24]. Compared with RNase P, RNase Z is very conserved in various species and belongs to the β-lactamase superfamily [25]. In addition, RNase Z has two isoforms; a smaller form, named RNase ZS, has been identified in the three domains of life (Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukaryote), whereas the other version, called RNase ZL, is an enzyme that is much larger than RNase ZS and found only in eukaryotes [26,27].

4. mt-tRNA Chemical Modification

After transcription by RNA polymerase, tRNA precursors usually undergo post-transcriptional processing, including numerous bases or sugar modifications, by various tRNA modifying enzymes [28]. These chemical modifications are critical for the stabilization of tRNA structure, allowing for proper interactions with other molecules and protection of tRNA from degradation [29]. The development of mass spectrometry has allowed us to provide an accurate way to identify unknown chemical modifications. To date, approximately 28 modified nucleosides spanning 46 positions have been found in human mt-tRNAs (Table 1) [30], and many of these modifications are broadly conserved in bacteria, eukaryotes, and archaea [31]. Among these, 15 modifications are called “universal modifications” since they are present in three domains of life [32] and mitochondria-specific residues at the wobble position 34. Actually, to maintain its normal function, position 34 is required for two taurine-associated modifications in mt-tRNAs: τm5U for tRNALeu(UUR) and tRNATrp and τm5s2U for tRNAGlu, tRNALys, and tRNAGln [33]. These modifications are essential for accurate protein translation, as well as codon and anticodon interactions [33]. For instance, the lack of τm5U34 modifications caused by diabetes-associated tRNALeu(UUR) A3243G mutation is responsible for translational deficiency [34].

Table 1.

Integrated view of human mt-tRNA modification.

Another important region for chemical modification is located at the anticodon stem, just 3′ to the anticodon [28]; modification at position 37 would keep the A-site anticodon functions and promote the accurate translational reading frame. By contrast, disease-associated mtDNA mutations such as tRNAMet A4435G, which disrupts position 37 modifications, would decrease the tRNA steady-state level and affect its functions [35].

5. tRNA Aminoacylation

The aminoacyl-tRNAs (aa-tRNAs), which are first catalyzed by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs) and then delivered to a macromolecular called ribosome, play critical roles in efficient protein synthesis [36]. In particular, mitochondrial aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (mt-aaRSs) are encoded by nDNA, ensure the proper attachment of each amino acid (AA) to its cognate mt-tRNA, and are imported into mitochondria from the cytoplasm [37]. There are two steps for universal aminoacylation reaction: (1) the mt-aaRS binds an AA with ATP, thus creating aminoacyladenylate and pyrophosphate; (2) the AA residue is brought proximal to the 3′ end of a specific mt-tRNA [38].

In humans, 17 mt-aaRSs are responsible for 20 standard AAs [39]. Genes encoding these proteins are designed as ARS2: for instance, AARS2 is referred to as the alanyl-tRNA synthetase. However, the GARS, which stands for glycyl-tRNA synthetase, encodes both cytosolic and mitochondrial proteins [40]; in addition, the KARS, which is responsible for lysyl-tRNA synthetase, employs splicing to form distinct mRNAs [41].

Theoretically, mutations in mt-aaRSs that impaired the maturations of mt-tRNAs were believed to have functional consequences for protein synthesis [42]. Recent experimental studies revealed that mt-aaRSs mutations predominantly affected the central nervous system (CNS) [43]. In the CNS-related pathologies, mutations in eight mt-aaRSs, including RARS2, NARS2, CARS2, IARS2, FARS2, PARS2, TARS2, and VARS2 led to mitochondrial myopathy, four mt-aaRSs, AARS2, DARS2, EARS2, and MARS2 mutations caused the leukodystrophies, and two mt-aaRSs, HARS2 and LARS2 mutations were involved in Perrault syndrome [44,45,46].

6. 3′ End CCA Addition

Functional mt-tRNA maturations require the 3′ end CCA addition [47]. In most organisms, this essential sequence is not encoded in the tRNA genes. Instead, this process is under the control of a CCA-adding enzyme called tRNA nucleotidyltransferase [48]. In homo sapiens, this gene is named TRNA-Nucleotidyltransferase 1 (TRNT1). There are 7 exons in this gene, which is localized at 3p26.2 and spans about 20-kb in length [49].

TRNT1 is a protein-coding gene. This essential enzyme functions by catalyzing the addition of the conserved nucleotide triplet CCA to the 3′ end of tRNA molecules [50]. Several steps must be tightly coordinated by the TRNT1 to ensure error-free CCA addition. To begin with, TRNT1 must identify tRNA and tRNA-like substrates, use only CTP and ATP, but exclude UTP and GTP, and switch specificity from C to A nucleotide after adding CC nucleotides and stop polymerization. Notably, in the absence of any of these steps, a tRNA molecule cannot be charged with an AA or perform any translational function [51].

Interestingly, there have recently been reports of mutations in the TRNT1 that reduced its catalytic activity, resulting in congenital sideroblastic anemia with immunodeficiency, fevers, and developmental delay (SIFD) [52,53]. Furthermore, mitochondrial translation may be impaired by mt-tRNASer(AGY) CCA addition associated with TRNT1 mutations, leading to a decrease in OXPHOS complexes abundance [54,55].

7. Import of tRNAs into Mitochondria

Most mitochondrial proteins are encoded by nuclear genomes and thus have to be imported into mitochondria from the cytosol. Furthermore, as the number of tRNA genes is insufficient for proper protein synthesis according to the genetic code and on the wobble rules, this lack of nuclear tRNAs could be compensated by the import of nuclear-encoded tRNAs [56]. About 40 years after its discovery in Tetrahymena pyriformis [57], tRNA import was recognized as a vital step in mitochondrial biogenesis [58,59]. In general, the import of tRNAs from the nucleus to the mitochondria consists of two key steps: the first is the targeting of tRNAs to the mitochondria; the second process involves their translocation via the mitochondrial membranes to reach the matrix [60,61].

In mammalian mitochondria, RNA import occurs through two different mechanisms: one involves cytosolic factors and an intact protein import system, while the other does not require soluble factors [62]. According to the first one, tRNAs are imported along the protein import pathway in a complex with a mitochondrial precursor. Initial studies were conducted in yeast, where tRNALys was co-imported with the pre-LysRS [63]. The second mechanism was characterized by the direct importation of tRNAs into isolated mitochondria without cytosolic factors; a case in point was the import of tRNAGln into mitochondria [64].

Mt-tRNA mutations cause respiratory deficiencies and lead to a wide range of mitochondrial disorders. Many of these mutations have unclear molecular consequences, and there are no effective treatments. However, the concept of mitochondrial tRNA import presents a novel treatment opinion; if a cytosolic tRNA were injected into the mitochondria that were capable of replacing the mutant mt-tRNA, it would be of great significance. A recent experimental study confirmed this hypothesis and found that in cybrid cells bearing myoclonic epilepsy with ragged-red fibers (MERRF)-associated tRNALys A8344G mutation, in addition to restoring tRNALys function, mitochondrial translation, complex respiratory activity, and other functions were partially rescued after import of tRNALys [65]. Thus, the use of tRNA import could be a novel strategy to cure mitochondrial disorders [66,67].

8. Cardiomyopathy-Associated mt-tRNA Mutations

8.1. tRNAPhe Mutation

The homoplasmic tRNAPhe T593C mutation was identified in patients with optic neuropathy, cardiomyopathy, and cognitive disability [68]. In human mitochondrial databases, such as mtDB (http://www.mtdb.igp.uu.se/, accessed on 15 August 2022) or Mitomap (http://www.mitomap.org/MITOMAP, accessed on 15 August 2022), this mutation was reported to be a rare polymorphism in the general population [69]. However, it may affect the progression of Leber’s Hereditary Optic Neuropathy (LHON) and non-syndromic hearing impairment in Asian populations [70,71]. Analysis of muscle biopsy samples revealed reduced values for oxygraphic Vmax of complexes I + III + IV, and that the respiratory chain complexes (RCC) I, III, and IV experienced a severe decrease in activity, highlighting the contribution of m.T593C mutation to mitochondrial dysfunction.

8.2. tRNAVal Mutations

The m.C1628T and m.G1644A mutations were identified in two Spanish patients with cardiomyopathy. Examination of muscle biopsy showed combined deficiencies of RCC I and IV [72]. Moreover, the m.C1628T or m.G1644A mutation markedly affected the steady-state level of tRNAVal, suggesting that these mutations can cause tRNA metabolism failure and contribute to cardiomyopathy [72].

8.3. tRNALeu(UUR) Mutations

A hot spot for pathogenic mutations associated with cardiomyopathy is mt-tRNALeu(UUR), including m.A3243G [73,74,75], m.T3250C [76], m.A3260G [77,78], m.T3271C [79], and m.C3303T [80,81] mutations. The well-known m.A3243G mutation is one of the most important causes of cardiomyopathy. In fact, the A-to-G transition at 3243 of mtDNA was reported to be the most prevalent mutation for various mitochondrial diseases such as diabetes [82], mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) [83], MERRF [84], and maternally transmitted diabetes and deafness (MIDD) [85]. Since mitochondrial disease is a multisystem presentation, the examination of skeletal muscle pathology was recommended for the diagnosis of mitochondrial cardiomyopathy [86].

In addition to the inefficient aminoacylation of tRNALeu(UUR) [87], m.A3243G also altered the mitochondrial RNA precursors, as well as its base modification [88]. Cybrids containing the m.A3243G mutation exhibited a 70–75% reduction in aminoacylated tRNALeu(UUR), contributing to a shortage of this tRNA, thus leading to defects in protein synthesis [89,90,91].

The m.T3250C mutation was described in patients harboring lactic acidosis, chronic fatigue, exercise intolerance, and muscle weakness [92,93]. Patient-derived fibroblast cell lines confirmed that this mutation affected mitochondrial function, evidenced by a lower level of ATP and RCC actives and a higher amount of ROS [76]. Thus, the m.T3250C mutation affected mitochondrial respiration and resulted in cardiomyopathy through incomplete penetrance.

The A-to-G transition at position 3260 was listed on the Mitomap database (http://www.mitomap.org/MITOMAP, accessed on 15 August 2022) as a confirmed mutation associated with maternal myopathy and cardiomyopathy [94,95]. In cybrid cells harboring the m.A3260G mutation, as compared to controls without this mutation, the rate of oxygen consumption, RCCs activities, and lactate production were markedly abnormal [77]. Furthermore, the m.A3260G mutation affected the respiratory chain functions and caused defects in the OXPHOS system [77].

Patients with MELAS-like syndrome, as well as diabetes, were traditionally reported to have the m.T3271C mutation [96,97,98]. Subjects with m.T3271C mutation exhibited a marked decrease in RCCs I + IV activities [99]; moreover, defects of τm5U modification at the anticodon wobble position caused by this mutation, aggravated the tRNALeu(UUR) metabolism failure, thereby resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction [100].

The heteroplasmic mutation m.C3303T was originally reported in a pedigree carrying cardiomyopathy and myopathy [101]. This mutation abolished the conserved base-pairing in the Acceptor arm of tRNALeu(UUR); in addition, there was a biochemical defect with RCCs I~IV, indicating that m.C3303T mutation was responsible for the impairment of mitochondrial protein translation [102,103].

8.4. tRNAIle Mutations

The homoplasmic m.T4277C mutation occurring in the D-arm of tRNAIle was identified in a patient with HCM and hearing impairment [104]. Skeletal muscle showed multiple changes in respiratory chain enzymes and a lower steady-state level of tRNAIle with m.T4277C mutation. Notably, approximately 70% reduction in tRNAIle steady-state level was observed in the skeletal muscle of the patients with this mutation, which is below the threshold for normal cell function, resulting in the clinical phenotype [104].

The heteroplasmic m.A4295G mutation is located directly 3′ end immediately to the anticodon stem of the tRNAIle, which is very conserved in various species [105]. Notably, the m.A4295G mutation introduced an m1G37 modification of tRNAIle, which was catalyzed by methyltransferase 5 (TRMT5) [106]. Simulations of molecular dynamics suggested that the m.A4295G mutation altered the structure and function of tRNAIle, as evidenced by enhanced Tm, structural alternations, and instability of mutated tRNA. Using in vitro processing experiments, the m.A4295G mutation was found to reduce the tRNAIle 5′ end processing efficiency [107]. Therefore, the m.A4295G mutation may affect the OXPHOS system and lead to mitochondrial dysfunction.

The m.A4300G in tRNAIle is regarded as a pathogenic mutation for maternally inherited cardiomyopathy [108]. Molecular and biochemical analysis suggested that the m.A4300G mutation significantly decreased the RCCs, as compared with the controls without this mutation [109]. Furthermore, Northern blot analysis demonstrated that the m.A4300G caused ~45% reductions in steady-state levels in tRNAIle [109].

The m.A4317G mutation in tRNAIle affected tRNA by forming an abnormal stable structure in the TψC loop, thus increasing the Tm value [110]. The changes in secondary structure can influence the tRNAIle maturations, such as CCA addition in the 3′end [111]. Moreover, the m.A4317G mutation was reported to decrease isoleucylation significantly and was involved in the pathogenesis of fatal infantile cardiomyopathy [112].

Interestingly, an m.4322dupC mutation in the tRNAIle gene was reported to be associated with DCM. This insertion was present heteroplasmic in blood and muscle. Biochemical analysis showed that the m.4322dupC reduced levels of RCC activities [113].

8.5. tRNATrp Mutation

The m.G5521A mutation, as well as the CO2 G8249A mutation, was reported in Tunisian patients with cardiomyopathy [114]. The m.G5521A mutation occurred at the D-arm of tRNATrp, which might disrupt the secondary structure and functions of this tRNA, thereby causing a reduction in mitochondrial protein synthesis [101].

8.6. tRNACys Mutation

The homoplasmic m.A5814G mutation was first reported in an infant manifesting DCM, MELAS [115]. The m.A5814G mutation may affect the secondary structure of the tRNACys gene, altering the highly conserved last pairing of the D-arm region [116]. Interestingly, the tRNALeu(UUR) A3252G, which occurred at the same position as the m.A5814G, was regarded as a pathogenic mutation for MELAS-like syndrome [117]. Therefore, the m.A5814G mutation may have the same impact on tRNA translation and lead to the impairment of mitochondrial function.

8.7. tRNASer(UCN) Mutation

The homoplasmic m.A7495G mutation abolished a very conserved Watson–Crick base-pairing in the D-arm of tRNASer(UCN). Mutation at that position was critical for mt-tRNA structure and function. Moreover, a significant decrease in COX and Complex I activities was observed as compared to controls [118], indicating that this mutation may affect OXPHOS function.

8.8. tRNALys Mutations

The heteroplasmic m.T8306C mutation in the tRNALys gene was reported in a patient with severe late-onset of myopathy, myoclonus, leukoencephalopathy, HCM, and metabolic syndrome [119]. This change disrupted a T-A bond in the D-arm of tRNA, a nucleotide that was well conserved via evolution and is likely to have functional importance. Biochemical analysis of complex activities revealed a multiple defect in RCCs (I + III + IV), and single fiber analysis demonstrated that this mutation segregated with COX-deficient fibers [120].

The well-known m.A8344G mutation is commonly associated with MERRF [121,122]. In addition, this mutation is associated with cardiomyopathy based on a recent study [123]. Using cybrid cells with this mutation, the m.A8344G mutation was found to cause a defect in τm5s2U modification [124]. Importantly, tRNALys, without this modification, was unable to translate its genetic codons (AAA or AAG) because of the complete loss of codon and anticodon interactions on the ribosome [125]. Thus, the lack of wobble modification caused by m.A8343G mutation led to a translational defect, contributing to mitochondrial dysfunction [126].

In addition, the heteroplasmic m.G8363A was first described in a US family with inherited cardiomyopathy and hearing impairment [127]. The m.G8363A mutation abolished the conserved base-pairing in the Acceptor arm of tRNALys and may affect the tRNA structure and function. Single-fiber PCR analysis suggested a significant link between mutant mtDNA and impaired biochemical activities [128]. Moreover, the m.G8363A mutation caused a marked reduction in its aminoacylation ability, suggesting that this mutation was definitely pathogenic for cardiomyopathy [129].

8.9. tRNAGly Mutation

The heteroplasmic tRNAGly T9997C mutation was reported in a multiplex family manifesting non-obstructive cardiomyopathy [130]. This mutation affected the position adjacent to the Acceptor arm of tRNAGly. The m.T9997C is very conserved in invertebrates and mammals. Functional analysis indicated that the m.T9997C mutation reduced the activities of RCCs and protein synthesis [131].

8.10. tRNAHis Mutation

The m.G12192A mutation was originally reported in a Japanese patient who had reduced contraction of the left ventricle [132]. Furthermore, the co-occurrence of m.G12192A and m.G11778A mutations was detected in subjects with LHON and cardiomyopathy [133]. It is interesting to note that the m.G12192A mutation occurred at the TψC loop of tRNAHis, which was conserved from different vertebrates; in addition, a significant reduction in ATP and enhanced ROS levels were found in cell lines derived from patients carrying this mutation [134], emphasizing the contributions of m.G12192A mutation to mitochondrial dysfunction.

8.11. tRNALeu(CUN) Mutation

The mitochondrial heteroplasmic m.T12297C mutation affecting a highly conserved nucleotide (adjacent to the anticodon triple) was reported in an Italian family with cardiomyopathy and endocardial fibroelastosis [135]. Interestingly, the m.T12297C mutation played an important role in the interactions between mRNA and anticodon; therefore, mutant tRNALeu(CUN) was less stable than the wild-type version of this tRNA [136]. Patients harboring this mutation exhibited a significant reduction in RCC I activity, suggesting a positive link between this mutation and cardiomyopathy [137].

8.12. tRNAGlu Mutation

The m.T14709C affecting a conserved position in the anticodon stem of tRNAGlu has been described in patients with diabetes and myopathy [138,139,140]. Functional analysis using blue native PAGE showed an increased mtDNA content and decreased RCC activities, suggesting that the m.T14709C mutation was pathogenic for this disease [141].

8.13. tRNAThr Mutation

The m.A15924G mutation occurs at the extremely conserved nucleotide of tRNAThr, which is the last base pair of the anticodon stem adjacent to the anticodon loop of this tRNA [16]. Interestingly, the m.A15924G mutation abolished the Watson–Crick base-pairing and may result in the failure in tRNA metabolism. Functional assessment of DCM patients with m.A15924G mutation revealed a deficiency in complex IV activity as compared with controls suggesting a direct pathogenic role for DCM [142,143].

9. Conclusions and Future Prospects

mt-tRNA mutations were common among patients with cardiomyopathy (Table 2), although the exact molecular mechanisms are not fully understood. A number of mt-tRNA mutations have been identified in the past decades. mt-tRNA pathogenic mutations have structural and functional consequences, such as affecting the tRNA structure, altering 5′ or 3′ processing of tRNAs, and leading to defects in chemical modifications. Thus, these mutations would impair the normal functions of the RCCs, thereby exacerbating the mitochondrial dysfunction that is responsible for cardiomyopathy.

Table 2.

Summary of cardiomyopathy-associated mt-tRNA mutations.

The diagnosis of cardiomyopathy requires ultrastructural and enzymatic histochemical evidence due to the difficulty of proving pathogenicity by genetic mutation alone. Thus, not only a genetic approach but also pathological and enzymatic histochemical diagnosis should be used as much as possible to confirm the diagnosis of mitochondrial cardiomyopathy [144].

Author Contributions

Y.D., B.G., and J.H. conceived, drafted, edited, and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by grants from Science Technology of Zhejiang Province (No. 2020C030318), Ministry of Public Health of Zhejiang Province (No. 2021RC022), Hangzhou Bureau of Science and Technology (No. 20201203B210 and 20201203B178), Hangzhou Municipal Health Commission (No. Z20210019; ZD20220010 and OO20190131).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Maron, B.J.; Towbin, J.A.; Thiene, G.; Antzelevitch, C.; Corrado, D.; Arnett, D.; Moss, A.J.; Seidman, C.E.; Young, J.B.; American Heart Association; et al. Contemporary definitions and classification of the cardiomyopathies: An American Heart Association Scientific Statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research and Functional Genomics and Translational Biology Interdisciplinary Working Groups; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation 2006, 113, 1807–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, P.; Andersson, B.; Arbustini, E.; Bilinska, Z.; Cecchi, F.; Charron, P.; Dubourg, O.; Kühl, U.; Maisch, B.; McKenna, W.J.; et al. Classification of the cardiomyopathies: A position statement from the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2008, 29, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, P.; McKenna, W.; Bristow, M.; Maisch, B.; Mautner, B.; O’Connell, J.; Olsen, E.; Thiene, G.; Goodwin, J.; Gyarfas, I.; et al. Report of the 1995 World Health Organization/International Society and Federation of Cardiology Task Force on the Definition and Classification of cardiomyopathies. Circulation 1996, 93, 841–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagiatakis, C.; Di Mauro, V. The emerging role of epigenetics in therapeutic targeting of cardiomyopathies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asatryan, B.; Medeiros-Domingo, A. Translating emerging molecular genetic insights into clinical practice in inherited cardiomyopathies. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 96, 993–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mestroni, L.; Rocco, C.; Gregori, D.; Sinagra, G.; Di Lenarda, A.; Miocic, S.; Vatta, M.; Pinamonti, B.; Muntoni, F.; Caforio, A.L.; et al. Familial dilated cardiomyopathy: Evidence for genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity. Heart Muscle Disease Study Group. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1999, 34, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, D.P.; Johnson, N.M. Genetic evaluation of familial cardiomyopathy. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2008, 1, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, D.A.; Das, A.M. Control of mitochondrial ATP synthesis in the heart. Biochem. J. 1991, 280, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.C.; Wang, T.T.; Zheng, L.; Hua, F.; Li, J.J. The role of mitochondrial biogenesis dysfunction in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Biomol. Ther. 2022, 30, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, M.; Sandi, C. The social nature of mitochondria: Implications for human health. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 120, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, O.; Turnbull, D. Mitochondrial DNA disease-molecular insights and potential routes to a cure. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 325, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoya, J.; Ojala, D.; Attardi, G. Distinctive features of the 5’-terminal sequences of the human mitochondrial mRNAs. Nature 1981, 290, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandon, M.C.; Lott, M.T.; Nguyen, K.C.; Spolim, S.; Navathe, S.B.; Baldi, P.; Wallace, D.C. MITOMAP: A human mitochondrial genome database--2004 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, D611–D613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, L.J.; Liang, M.H.; Kwon, H.; Park, J.; Bai, R.K.; Tan, D.J. Comprehensive scanning of the entire mitochondrial genome for mutations. Clin. Chem. 2002, 48, 1901–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, D.C. A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: A dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2005, 39, 359–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, S.; Bankier, A.T.; Barrell, B.G.; de Bruijn, M.H.; Coulson, A.R.; Drouin, J.; Eperon, I.C.; Nierlich, D.P.; Roe, B.A.; Sanger, F.; et al. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature 1981, 290, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pak, D.; Root-Bernstein, R.; Burton, Z.F. tRNA structure and evolution and standardization to the three nucleotide genetic code. Transcription 2017, 8, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bruijn, M.H.; Schreier, P.H.; Eperon, I.C.; Barrell, B.G.; Chen, E.Y.; Armstrong, P.W.; Wong, J.F.; Roe, B.A. A mammalian mitochondrial serine transfer RNA lacking the “dihydrouridine” loop and stem. Nucleic. Acids Res. 1980, 8, 5213–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Kawai, G.; Yokogawa, T.; Hayashi, N.; Kumazawa, Y.; Ueda, T.; Nishikawa, K.; Hirao, I.; Miura, K.; Watanabe, K. Higher-order structure of bovine mitochondrial tRNA(SerUGA): Chemical modification and computer modeling. Nucleic. Acids Res. 1994, 22, 5378–5384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobert, A.; Bruggeman, M.; Giegé, P. Involvement of PIN-like domain nucleases in tRNA processing and translation regulation. IUBMB Life 2019, 71, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, S. A view of RNase P. Mol. Biosyst. 2007, 3, 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzmann, J.; Frank, P.; Löffler, E.; Bennett, K.L.; Gerner, C.; Rossmanith, W. RNase P without RNA: Identification and functional reconstitution of the human mitochondrial tRNA processing enzyme. Cell 2008, 135, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilardo, E.; Nachbagauer, C.; Buzet, A.; Taschner, A.; Holzmann, J.; Rossmanith, W. A subcomplex of human mitochondrial RNase P is a bifunctional methyltransferase--extensive moonlighting in mitochondrial tRNA biogenesis. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2012, 40, 11583–11593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maraia, R.J.; Lamichhane, T.N. 3’ processing of eukaryotic precursor tRNAs. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2011, 2, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rammelt, C.; Rossmanith, W. Repairing tRNA termini: News from the 3′ end. RNA Biol. 2016, 13, 1182–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossmanith, W. Localization of human RNase Z isoforms: Dual nuclear/mitochondrial targeting of the elac2 gene product by alternative translation initiation. PLoS One. 2011, 6, e19152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, A.; Schilling, O.; Späth, B.; Marchfelder, A. The tRNase Z family of proteins: Physiological functions, substrate specificity and structural properties. Biol. Chem. 2005, 386, 1253–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Yacoubi, B.; Bailly, M.; de Crécy-Lagard, V. Biosynthesis and function of posttranscriptional modifications of transfer RNAs. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2012, 46, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machnicka, M.A.; Milanowska, K.; Osman Oglou, O.; Purta, E.; Kurkowska, M.; Olchowik, A.; Januszewski, W.; Kalinowski, S.; Dunin-Horkawicz, S.; Rother, K.M.; et al. MODOMICS: A database of RNA modification pathways—2013 update. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2013, 41, D262–D267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.S.; Alfonzo, J.D.; Accornero, F. The importance of RNA modifications: From cells to muscle physiology. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2021, 19, e1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phizicky, E.M.; Alfonzo, J.D. Do all modifications benefit all tRNAs? FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriya, J.; Yokogawa, T.; Wakita, K.; Ueda, T.; Nishikawa, K.; Crain, P.F.; Hashizume, T.; Pomerantz, S.C.; McCloskey, J.A.; Kawai, G.; et al. A novel modified nucleoside found at the first position of the anticodon of methionine tRNA from bovine liver mitochondria. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 2234–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Suzuki, T.; Wada, T.; Saigo, K.; Watanabe, K. Taurine as a constituent of mitochondrial tRNAs: New insights into the functions of taurine and human mitochondrial diseases. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 6581–6589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirino, Y.; Goto, Y.; Campos, Y.; Arenas, J.; Suzuki, T. Specific correlation between the wobble modification deficiency in mutant tRNAs and the clinical features of a human mitochondrial disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 7127–7132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Xue, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; He, Q.; Wang, B.; Meng, F.; Wang, M.; Guan, M.X. A hypertension-associated mitochondrial DNA mutation introduces an m1G37 modification into tRNAMet, altering its structure and function. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 1425–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibba, M.; Söll, D. Quality control mechanisms during translation. Science 1999, 286, 1893–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibba, M.; Soll, D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000, 69, 617–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Schimmel, P.; Yang, X.L. Functional expansion of human tRNA synthetases achieved by structural inventions. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnefond, L.; Fender, A.; Rudinger-Thirion, J.; Giegé, R.; Florentz, C.; Sissler, M. Toward the full set of human mitochondrial aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases: Characterization of AspRS and TyrRS. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 4805–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiba, K.; Schimmel, P.; Motegi, H.; Noda, T. Human glycyl-tRNA synthetase. Wide divergence of primary structure from bacterial counterpart and species-specific aminoacylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 30049–30055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolkunova, E.; Park, H.; Xia, J.; King, M.P.; Davidson, E. The human lysyl-tRNA synthetase gene encodes both the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial enzymes by means of an unusual alternative splicing of the primary transcript. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 35063–35069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongkittichote, P.; Magistrati, M.; Shimony, J.S.; Smyser, C.D.; Fatemi, S.A.; Fine, A.S.; Bellacchio, E.; Dallabona, C.; Shinawi, M. Functional analysis of missense DARS2 variants in siblings with leukoencephalopathy with brain stem and spinal cord involvement and lactate elevation. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2022, 136, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fine, A.S.; Nemeth, C.L.; Kaufman, M.L.; Fatemi, A. Mitochondrial aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase disorders: An emerging group of developmental disorders of myelination. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2019, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Serrano, L.E.; Karim, L.; Pierre, F.; Schwenzer, H.; Rötig, A.; Munnich, A.; Sissler, M. Three human aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases have distinct sub-mitochondrial localizations that are unaffected by disease-associated mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 13604–13615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Serrano, L.E.; Chihade, J.W.; Sissler, M. When a common biological role does not imply common disease outcomes: Disparate pathology linked to human mitochondrial aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 5309–5320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konovalova, S.; Tyynismaa, H. Mitochondrial aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in human disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2013, 108, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schürer, H.; Schiffer, S.; Marchfelder, A.; Mörl, M. This is the end: Processing, editing and repair at the tRNA 3′-terminus. Biol. Chem. 2001, 382, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betat, H.; Rammelt, C.; Mörl, M. tRNA nucleotidyltransferases: Ancient catalysts with an unusual mechanism of polymerization. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 1447–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaike, T.; Suzuki, T.; Tomari, Y.; Takemoto-Hori, C.; Negayama, F.; Watanabe, K.; Ueda, T. Identification and characterization of mammalian mitochondrial tRNA nucleotidyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 40041–40049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, K.; Shigematsu, M.; Loher, P.; Honda, S.; Rigoutsos, I.; Kirino, Y. Exploration of CCA-added RNAs revealed the expression of mitochondrial non-coding RNAs regulated by CCA-adding enzyme. RNA Biol. 2019, 16, 1817–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellner, K.; Betat, H.; Mörl, M. A tRNA’s fate is decided at its 3’ end: Collaborative actions of CCA-adding enzyme and RNases involved in tRNA processing and degradation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2018, 1861, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, P.K.; Schmitz-Abe, K.; Kennedy, E.K.; Mamady, H.; Naas, T.; Durie, D.; Campagna, D.R.; Lau, A.; Sendamarai, A.K.; Wiseman, D.H.; et al. Mutations in TRNT1 cause congenital sideroblastic anemia with immunodeficiency, fevers, and developmental delay (SIFD). Blood 2014, 124, 2867–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Deng, Q.; He, X.; Chen, D.; Hang, S.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Y. Two cases of sideroblastic anemia with B-cell immunodeficiency, periodic fevers, and developmental delay (SIFD) syndrome in Chinese Han children caused by novel compound heterozygous variants of the TRNT1 gene. Clin. Chim. Acta 2021, 521, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasarman, F.; Thiffault, I.; Weraarpachai, W.; Salomon, S.; Maftei, C.; Gauthier, J.; Ellazam, B.; Webb, N.; Antonicka, H.; Janer, A.; et al. The 3’ addition of CCA to mitochondrial tRNASer(AGY) is specifically impaired in patients with mutations in the tRNA nucleotidyl transferase TRNT1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 2841–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liwak-Muir, U.; Mamady, H.; Naas, T.; Wylie, Q.; McBride, S.; Lines, M.; Michaud, J.; Baird, S.D.; Chakraborty, P.K.; Holcik, M. Impaired activity of CCA-adding enzyme TRNT1 impacts OXPHOS complexes and cellular respiration in SIFD patient-derived fibroblasts. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2016, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, E.A.; Siegal, E.; Gregory, R.I. tRNA dysregulation and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyama, Y. The origins of mitochondrial ribonucleic acids in Tetrahymena pyriformis. Biochemistry 1967, 6, 2829–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lithgow, T.; Schneider, A. Evolution of macromolecular import pathways in mitochondria, hydrogenosomes and mitosomes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 799–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, T.; Duchêne, A.M.; Maréchal-Drouard, L. Recent advances in tRNA mitochondrial import. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2008, 33, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, M.A.; Rinehart, J.J.; Krett, B.; Duvezin-Caubet, S.; Reichert, A.S.; Söll, D.; Alfonzo, J.D. Mammalian mitochondria have the innate ability to import tRNAs by a mechanism distinct from protein import. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 9186–9191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, E.V.; Chicherin, I.V.; Baleva, M.V.; Entelis, N.S.; Tarassov, I.A.; Kamenski, P.A. Procedure for Purification of Recombinant preMsk1p from E. coli Determines Its Properties as a Factor of tRNA Import into Yeast Mitochondria. Biochemistry 2016, 81, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Entelis, N.S.; Kolesnikova, O.A.; Martin, R.P.; Tarassov, I.A. RNA delivery into mitochondria. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev. 2001, 49, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarassov, I.; Entelis, N.; Martin, R.P. Mitochondrial import of a cytoplasmic lysine-tRNA in yeast is mediated by cooperation of cytoplasmic and mitochondrial lysyl-tRNA synthetases. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 3461–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinehart, J.; Krett, B.; Rubio, M.A.; Alfonzo, J.D.; Soll, D. Saccharomyces cerevisiae imports the cytosolic pathway for Gln-tRNA synthesis into the mitochondrion. Genes. Dev. 2005, 19, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikova, O.A.; Entelis, N.S.; Jacquin-Becker, C.; Goltzene, F.; Chrzanowska-Lightowlers, Z.M.; Lightowlers, R.N.; Martin, R.P.; Tarassov, I. Nuclear DNA-encoded tRNAs targeted into mitochondria can rescue a mitochondrial DNA mutation associated with the MERRF syndrome in cultured human cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004, 13, 2519–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikova, O.A.; Entelis, N.S.; Mireau, H.; Fox, T.D.; Martin, R.P.; Tarassov, I.A. Suppression of mutations in mitochondrial DNA by tRNAs imported from the cytoplasm. Science 2000, 289, 1931–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahata, B.; Bhattacharyya, S.N.; Mukherjee, S.; Adhya, S. Correction of translational defects in patient-derived mutant mitochondria by complex-mediated import of a cytoplasmic tRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 5141–5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charif, M.; Titah, S.M.; Roubertie, A.; Desquiret-Dumas, V.; Gueguen, N.; Meunier, I.; Leid, J.; Massal, F.; Zanlonghi, X.; Mercier, J.; et al. Optic neuropathy, cardiomyopathy, cognitive disability in patients with a homozygous mutation in the nuclear MTO1 and a mitochondrial MT-TF variant. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2015, 167A, 2366–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingman, M.; Gyllensten, U. MtDB: Human Mitochondrial Genome Database, a resource for population genetics and medical sciences. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2006, 34, D749–D751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.M.; Bandelt, H.J.; Jia, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Yu, D.; Wang, D.; Zhuang, X.Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yao, Y.G. Is mitochondrial tRNA(phe) variant m.593T>C a synergistically pathogenic mutation in Chinese LHON families with m.11778G>A? PLoS One. 2011, 6, e26511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Nie, Z.; Wang, F.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.W.; Zheng, J.; Guo, Y.F.; Guan, M.X. Late onset nonsyndromic hearing loss in a Dongxiang Chinese family is associated with the 593T>C variant in the mitochondrial tRNAPhe gene. Mitochondrion 2017, 35, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arredondo, J.J.; Gallardo, M.E.; García-Pavía, P.; Domingo, V.; Bretón, B.; García-Silva, M.T.; Sedano, M.J.; Martín, M.A.; Arenas, J.; Cervera, M.; et al. Mitochondrial tRNA valine as a recurrent target for mutations involved in mitochondrial cardiomyopathies. Mitochondrion 2012, 12, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollingsworth, K.G.; Gorman, G.S.; Trenell, M.I.; McFarland, R.; Taylor, R.W.; Turnbull, D.M.; MacGowan, G.A.; Blamire, A.M.; Chinnery, P.F. Cardiomyopathy is common in patients with the mitochondrial DNA m.3243A>G mutation and correlates with mutation load. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2012, 22, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilarinho, L.; Santorelli, F.M.; Rosas, M.J.; Tavares, C.; Melo-Pires, M.; DiMauro, S. The mitochondrial A3243G mutation presenting as severe cardiomyopathy. J. Med. Genet. 1997, 34, 607–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stalder, N.; Yarol, N.; Tozzi, P.; Rotman, S.; Morris, M.; Fellmann, F.; Schwitter, J.; Hullin, R. Mitochondrial A3243G mutation with manifestation of acute dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ. Heart Fail. 2012, 5, e1–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, T.; Lou, X.; Slone, J.; Brown, J.; Bromwell, M.; Liu, J.; Bai, R.; Haude, K.; Balog, A.; Cui, H.; et al. Mitochondrial genome variant m.3250T>C as a possible risk factor for mitochondrial cardiomyopathy. Hum. Mutat. 2021, 42, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, C.; Tiranti, V.; Carrara, F.; Dallapiccola, B.; DiDonato, S.; Zeviani, M. Defective respiratory capacity and mitochondrial protein synthesis in transformant cybrids harboring the tRNA(Leu(UUR)) mutation associated with maternally inherited myopathy and cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Investig. 1994, 93, 1102–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, B.S.; Feigenbaum, A.S.; Robinson, B.H.; Dipchand, A.I.; Simon, D.K.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. MELAS syndrome, cardiomyopathy, rhabdomyolysis, and autism associated with the A3260G mitochondrial DNA mutation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 402, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisca, G.; Fiorillo, C.; Nesti, C.; Trucco, F.; Derchi, M.; Andaloro, A.; Assereto, S.; Morcaldi, G.; Pedemonte, M.; Minetti, C.; et al. Early onset cardiomyopathy associated with the mitochondrial tRNALeu((UUR)) 3271T>C MELAS mutation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 458, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.D.; Shanske, S.; Bruno, C.; Perszyk, A.A. Maternally inherited mitochondrial cardiomyopathy associated with a C-to-T transition at nucleotide 3303 of mitochondrial DNA in the tRNA(Leu(UUR)) gene. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 1999, 2, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, G.; Santorelli, F.M.; Shanske, S.; Whitley, C.B.; Schimmenti, L.A.; Smith, S.A.; DiMauro, S. A new mtDNA mutation in the tRNA(Leu(UUR)) gene associated with maternally inherited cardiomyopathy. Hum. Mutat. 1994, 3, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Zhang, D.; Jin, Q.; Teng, Y.; Yao, X.; Zhao, T.; Xu, X.; Jin, Y. Mutational analysis of mitochondrial tRNA genes in 200 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 5719–5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.N.; Yoon, C.S.; Lee, Y.M. Correlation of serum biomarkers and magnetic resonance spectroscopy in monitoring disease progression in patients With mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes due to mtDNA A3243G mutation. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkaouar-Rebai, E.; Tlili, A.; Masmoudi, S.; Belguith, N.; Charfeddine, I.; Mnif, M.; Triki, C.; Fakhfakh, F. Mutational analysis of the mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) gene in Tunisian patients with mitochondrial diseases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 355, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorns, C.; Widjaja, A.; Boeck, N.; Skamira, C.; Zühlke, H. Maternally-inherited diabetes and deafness: Report of two affected German families with the A3243G mitochondrial DNA mutation. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 1998, 106, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschauer, M.; Neudecker, S.; Müller, T.; Gellerich, F.N.; Zierz, S. Higher proportion of mitochondrial A3243G mutation in blood than in skeletal muscle in a patient with cardiomyopathy and hearing loss. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2000, 70, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasukawa, T.; Suzuki, T.; Ishii, N.; Ueda, T.; Ohta, S.; Watanabe, K. Defect in modification at the anticodon wobble nucleotide of mitochondrial tRNA(Lys) with the MERRF encephalomyopathy pathogenic mutation. FEBS Lett. 2000, 467, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, M.; Florentz, C.; Chomyn, A.; Attardi, G. Search for differences in post-transcriptional modification patterns of mitochondrial DNA-encoded wild-type and mutant human tRNALys and tRNALeu(UUR). Nucleic. Acids Res. 1999, 27, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chomyn, A.; Enriquez, J.A.; Micol, V.; Fernandez-Silva, P.; Attardi, G. The mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episode syndrome-associated human mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) mutation causes aminoacylation deficiency and concomitant reduced association of mRNA with ribosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 19198–19209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, G.M.; Hensbergen, P.J.; van Bussel, F.J.; Balog, C.I.; Maassen, J.A.; Deelder, A.M.; Raap, A.K. The A3243G tRNALeu(UUR) mutation induces mitochondrial dysfunction and variable disease expression without dominant negative acting translational defects in complex IV subunits at UUR codons. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007, 16, 2472–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.P.; Koga, Y.; Davidson, M.; Schon, E.A. Defects in mitochondrial protein synthesis and respiratory chain activity segregate with the tRNA(Leu(UUR)) mutation associated with mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes. Mol. Cell Biol. 1992, 12, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpa, J.; Cruz-Martínez, A.; Campos, Y.; Gutiérrez-Molina, M.; García-Rio, F.; Pérez-Conde, C.; Martín, M.A.; Rubio, J.C.; Del Hoyo, P.; Arpa-Fernández, A.; et al. Prevalence and progression of mitochondrial diseases: A study of 50 patients. Muscle Nerve 2003, 28, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darin, N.; Hedberg-Oldfors, C.; Kroksmark, A.K.; Moslemi, A.R.; Kollberg, G.; Oldfors, A. Benign mitochondrial myopathy with exercise intolerance in a large multigeneration family due to a homoplasmic m.3250T>C mutation in MTTL1. Eur. J. Neurol. 2017, 24, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishino, I.; Komatsu, M.; Kodama, S.; Horai, S.; Nonaka, I.; Goto, Y. The 3260 mutation in mitochondrial DNA can cause mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes (MELAS). Muscle Nerve 1996, 19, 1603–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeviani, M.; Gellera, C.; Antozzi, C.; Rimoldi, M.; Morandi, L.; Villani, F.; Tiranti, V.; DiDonato, S. Maternally inherited myopathy and cardiomyopathy: Association with mutation in mitochondrial DNA tRNA(Leu)(UUR). Lancet 1991, 338, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, H.F.; Liang, W.C.; Zhang, Q.; Goto, Y.; Jong, Y.J. Clinical and genetic features in a MELAS child with a 3271T>C mutation. Pediatr. Neurol. 2008, 38, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Tsukuda, K.; Atsumi, Y.; Goto, Y.; Hosokawa, K.; Asahina, T.; Nonaka, I.; Matsuoka, K.; Oka, Y. Clinical picture of a case of diabetes with mitochondrial tRNA mutation at position 3271. Diabetes Care 1996, 19, 1304–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, Y. Clinical features of MELAS and mitochondrial DNA mutations. Muscle Nerve 1995, 18 (Suppl. S14), S107–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, A.; Koga, Y.; Akita, Y.; Fukiyama, R.; Ueki, I.; Yatsuga, S.; Matsuishi, T. Increased mitochondrial processing intermediates associated with three tRNA(Leu(UUR)) gene mutations. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2003, 13, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirino, Y.; Yasukawa, T.; Ohta, S.; Akira, S.; Ishihara, K.; Watanabe, K.; Suzuki, T. Codon-specific translational defect caused by a wobble modification deficiency in mutant tRNA from a human mitochondrial disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 15070–15075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, G.; Rana, M.; DiMuzio, A.; Uncini, A.; Tonali, P.; Servidei, S. A late-onset mitochondrial myopathy is associated with a novel mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) point mutation in the tRNA(Trp) gene. Neuromuscul. Disord. 1998, 8, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, C.; Kirby, D.M.; Koga, Y.; Garavaglia, B.; Duran, G.; Santorelli, F.M.; Shield, L.K.; Xia, W.; Shanske, S.; Goldstein, J.D.; et al. The mitochondrial DNA C3303T mutation can cause cardiomyopathy and/or skeletal myopathy. J. Pediatr. 1999, 135, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, Y.; García, A.; Eiris, J.; Fuster, M.; Rubio, J.C.; Martín, M.A.; del Hoyo, P.; Pintos, E.; Castro-Gago, M.; Arenas, J. Mitochondrial myopathy, cardiomyopathy and psychiatric illness in a Spanish family harbouring the mtDNA 3303C > T mutation. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2001, 24, 685–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perli, E.; Giordano, C.; Tuppen, H.A.; Montopoli, M.; Montanari, A.; Orlandi, M.; Pisano, A.; Catanzaro, D.; Caparrotta, L.; Musumeci, B.; et al. Isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase levels modulate the penetrance of a homoplasmic m.4277T>C mitochondrial tRNAIle mutation causing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merante, F.; Myint, T.; Tein, I.; Benson, L.; Robinson, B.H. An additional mitochondrial tRNA(Ile) point mutation (A-to-G at nucleotide 4295) causing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Hum. Mutat. 1996, 8, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, B.E.; Kozome, D.; Laurino, P. Efficient exploration of sequence space by sequence-guided protein engineering and design. Biochemistry 2022. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Zhou, M.; Xiao, Y.; Mao, X.; Zheng, J.; Lin, J.; Lin, T.; Ye, Z.; Cang, X.; Fu, Y.; et al. A deafness-associated tRNA mutation caused pleiotropic effects on the m1G37 modification, processing, stability and aminoacylation of tRNAIle and mitochondrial translation. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2021, 49, 1075–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casali, C.; d’Amati, G.; Bernucci, P.; DeBiase, L.; Autore, C.; Santorelli, F.M.; Coviello, D.; Gallo, P. Maternally inherited cardiomyopathy: Clinical and molecular characterization of a large kindred harboring the A4300G point mutation in mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1999, 33, 1584–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Taylor, R.W.; Giordano, C.; Davidson, M.M.; d’Amati, G.; Bain, H.; Hayes, C.M.; Leonard, H.; Barron, M.J.; Casali, C.; Santorelli, F.M.; et al. A homoplasmic mitochondrial transfer ribonucleic acid mutation as a cause of maternally inherited hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 41, 1786–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; He, Z.; Tang, X.; Zheng, J.; Jin, X.; Zhu, Y.; Ren, X.; Zhou, M.; Wang, M.; Gong, S.; et al. Contribution of the tRNAIle 4317A→G mutation to the phenotypic manifestation of the deafness-associated mitochondrial 12S rRNA 1555A→G mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 3321–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomari, Y.; Hino, N.; Nagaike, T.; Suzuki, T.; Ueda, T. Decreased CCA-addition in human mitochondrial tRNAs bearing a pathogenic A4317G or A10044G mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 16828–16833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degoul, F.; Brulé, H.; Cepanec, C.; Helm, M.; Marsac, C.; Leroux, J.; Giegé, R.; Florentz, C. Isoleucylation properties of native human mitochondrial tRNAIle and tRNAIle transcripts. Implications for cardiomyopathy-related point mutations (4269, 4317) in the tRNAIle gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998, 7, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahjoub, S.; Sternberg, D.; Boussaada, R.; Filaut, S.; Gmira, F.; Mechmech, R.; Jardel, C.; Arab, S.B. A novel mitochondrial DNA tRNAIle (m.4322dupC) mutation associated with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Diagn. Mol. Pathol. 2007, 16, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkaouar-Rebai, E.; Ben Mahmoud, A.; Chamkha, I.; Chabchoub, I.; Kammoun, T.; Hachicha, M.; Fakhfakh, F. A novel MT-CO2 m.8249G>A pathogenic variation and the MT-TW m.5521G>A mutation in patients with mitochondrial myopathy. Mitochondrial. DNA. 2014, 25, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karadimas, C.; Tanji, K.; Geremek, M.; Chronopoulou, P.; Vu, T.; Krishna, S.; Fakhfakh, F. A5814G mutation in mitochondrial DNA can cause mitochondrial myopathy and cardiomyopathy. J. Child. Neurol. 2001, 16, 531–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scuderi, C.; Borgione, E.; Musumeci, S.; Elia, M.; Castello, F.; Fichera, M.; Davidzon, G.; DiMauro, S. Severe encephalomyopathy in a patient with homoplasmic A5814G point mutation in mitochondrial tRNACys gene. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2007, 17, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morten, K.J.; Cooper, J.M.; Brown, G.K.; Lake, B.D.; Pike, D.; Poulton, J. A new point mutation associated with mitochondrial encephalomyopathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1993, 2, 2081–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjevic, D.; Brady, L.; Bai, R.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. Two novel mitochondrial tRNA mutations, A7495G (tRNASer(UCN)) and C5577T (tRNATrp), are associated with seizures and cardiac dysfunction. Mitochondrion. 2016, 31, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardaioli, E.; Malfatti, E.; Battisti, C.; Da Pozzo, P.; Rubegni, A.; Gallus, G.N.; Malandrini, A.; Federico, A. Sporadic myopathy, myoclonus, leukoencephalopathy, neurosensory deafness, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and insulin resistance associated with the mitochondrial 8306 T>C MTTK mutation. J. Neurol. Sci. 2012, 321, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarham, J.W.; Al-Dosary, M.; Blakely, E.L.; Alston, C.L.; Taylor, R.W.; Elson, J.L.; McFarland, R. A comparative analysis approach to determining the pathogenicity of mitochondrial tRNA mutations. Hum. Mutat. 2011, 32, 1319–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, M.G.; Nelson, I.; Sweeney, M.G.; Cooper, J.M.; Watkins, P.J.; Morgan-Hughes, J.A.; Harding, A.E. Congenital encephalomyopathy and adult-onset myopathy and diabetes mellitus: Different phenotypic associations of a new heteroplasmic mtDNA tRNA glutamic acid mutation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1995, 56, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Larsson, N.G.; Tulinius, M.H.; Holme, E.; Oldfors, A. Pathogenetic aspects of the A8344G mutation of mitochondrial DNA associated with MERRF syndrome and multiple symmetric lipomas. Muscle Nerve 1995, 18 (Suppl. S14), S102–S106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catteruccia, M.; Sauchelli, D.; Della Marca, G.; Primiano, G.; Cuccagna, C.; Bernardo, D.; Leo, M.; Camporeale, A.; Sanna, T.; Cianfoni, A.; et al. “Myo-cardiomyopathy” is commonly associated with the A8344G “MERRF” mutation. J. Neurol. 2015, 262, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasukawa, T.; Suzuki, T.; Ueda, T.; Ohta, S.; Watanabe, K. Modification defect at anticodon wobble nucleotide of mitochondrial tRNAs(Leu)(UUR) with pathogenic mutations of mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 4251–4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasukawa, T.; Suzuki, T.; Ishii, N.; Ohta, S.; Watanabe, K. Wobble modification defect in tRNA disturbs codon-anticodon interaction in a mitochondrial disease. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 4794–4802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasukawa, T.; Kirino, Y.; Ishii, N.; Holt, I.J.; Jacobs, H.T.; Makifuchi, T.; Fukuhara, N.; Ohta, S.; Suzuki, T.; Watanabe, K. Wobble modification deficiency in mutant tRNAs in patients with mitochondrial diseases. FEBS Lett. 2005, 579, 2948–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santorelli, F.M.; Mak, S.C.; El-Schahawi, M.; Casali, C.; Shanske, S.; Baram, T.Z.; Madrid, R.E.; DiMauro, S. Maternally inherited cardiomyopathy and hearing loss associated with a novel mutation in the mitochondrial tRNA(Lys) gene (G8363A). Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1996, 58, 933–939. [Google Scholar]

- Virgilio, R.; Ronchi, D.; Bordoni, A.; Fassone, E.; Bonato, S.; Donadoni, C.; Torgano, G.; Moggio, M.; Corti, S.; Bresolin, N.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA G8363A mutation in the tRNA Lys gene: Clinical, biochemical and pathological study. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009, 281, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, B.; Mas, J.A.; Patrono, C.; Fernández-Moreno, M.A.; González-Vioque, E.; Campos, Y.; Carrozzo, R.; Martín, M.A.; del Hoyo, P.; Santorelli, F.M.; et al. Comparative analysis of the pathogenic mechanisms associated with the G8363A and A8296G mutations in the mitochondrial tRNA(Lys) gene. Biochem. J. 2005, 387, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merante, F.; Tein, I.; Benson, L.; Robinson, B.H. Maternally inherited hypertrophic cardiomyopathy due to a novel T-to-C transition at nucleotide 9997 in the mitochondrial tRNA(glycine) gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1994, 55, 437–446. [Google Scholar]

- Raha, S.; Merante, F.; Shoubridge, E.; Myint, A.T.; Tein, I.; Benson, L.; Johns, T.; Robinson, B.H. Repopulation of rho0 cells with mitochondria from a patient with a mitochondrial DNA point mutation in tRNA(Gly) results in respiratory chain dysfunction. Hum. Mutat. 1999, 13, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.S.; Tanaka, M.; Suzuki, J.; Hemmi, C.; Toyo-oka, T. A novel homoplasmic mutation in mtDNA with a single evolutionary origin as a risk factor for cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000, 67, 1617–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mimaki, M.; Ikota, A.; Sato, A.; Komaki, H.; Akanuma, J.; Nonaka, I.; Goto, Y. A double mutation (G11778A and G12192A) in mitochondrial DNA associated with Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy and cardiomyopathy. J. Hum. Genet. 2003, 48, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ding, Y.; Teng, Y.S.; Zhuo, G.C.; Xia, B.H.; Leng, J.H. The mitochondrial tRNAHis G12192A mutation may modulate the clinical expression of deafness-associated tRNAThr G15927A mutation in a Chinese pedigree. Curr. Mol. Med. 2019, 19, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessa, A.; Vilarinho, L.; Casali, C.; Santorelli, F.M. MtDNA-related idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 1999, 7, 847–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Grasso, M.; Diegoli, M.; Brega, A.; Campana, C.; Tavazzi, L.; Arbustini, E. The mitochondrial DNA mutation T12297C affects a highly conserved nucleotide of tRNA(Leu(CUN)) and is associated with dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 9, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Brautbar, A.; Chan, A.K.; Dzwiniel, T.; Li, F.Y.; Waters, P.J.; Graham, B.H.; Wong, L.J. Two mtDNA mutations 14487T>C (M63V, ND6) and 12297T>C (tRNA Leu) in a Leigh syndrome family. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2009, 96, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damore, M.E.; Speiser, P.W.; Slonim, A.E.; New, M.I.; Shanske, S.; Xia, W.; Santorelli, F.M.; DiMauro, S. Early onset of diabetes mellitus associated with the mitochondrial DNA T14709C point mutation: Patient report and literature review. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999, 12, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, M.G.; Nelson, I.P.; Morgan-Hughes, J.A.; Harding, A.E. Impaired mitochondrial translation in human myoblasts harbouring the mitochondrial DNA tRNA lysine 8344 A-->G (MERRF) mutation: Relationship to proportion of mutant mitochondrial DNA. J. Neurol. Sci. 1995, 130, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Bonilla, E.; Manfredi, G.; DiMauro, S.; Moraes, C.T. Segregation patterns of a novel mutation in the mitochondrial tRNA glutamic acid gene associated with myopathy and diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1995, 56, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hove, J.L.; Freehauf, C.; Miyamoto, S.; Vladutiu, G.D.; Pancrudo, J.; Bonilla, E.; Lovell, M.A.; Mierau, G.W.; Thomas, J.A.; Shanske, S. Infantile cardiomyopathy caused by the T14709C mutation in the mitochondrial tRNA glutamic acid gene. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2008, 167, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruppert, V.; Nolte, D.; Aschenbrenner, T.; Pankuweit, S.; Funck, R.; Maisch, B. Novel point mutations in the mitochondrial DNA detected in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy by screening the whole mitochondrial genome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 318, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, K.L.; Aprille, J.R.; Ernst, S.G. Mitochondrial tRNA(thr) mutation in fatal infantile respiratory enzyme deficiency. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991, 176, 1112–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, A.; Murayama, K.; Okazaki, Y.; Imai-Okazaki, A.; Ohtake, A.; Takakuwa, E.; Yamazawa, H.; Izumi, G.; Abe, J.; Nagai, A.; et al. Advanced pathological study for definite diagnosis of mitochondrial cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Pathol. 2020, 74, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).