Impact of Hidradenitis Suppurativa Surgical Treatment on Health-Related Life Quality

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Gathering

2.2. Quality-of-Life Survey

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Data

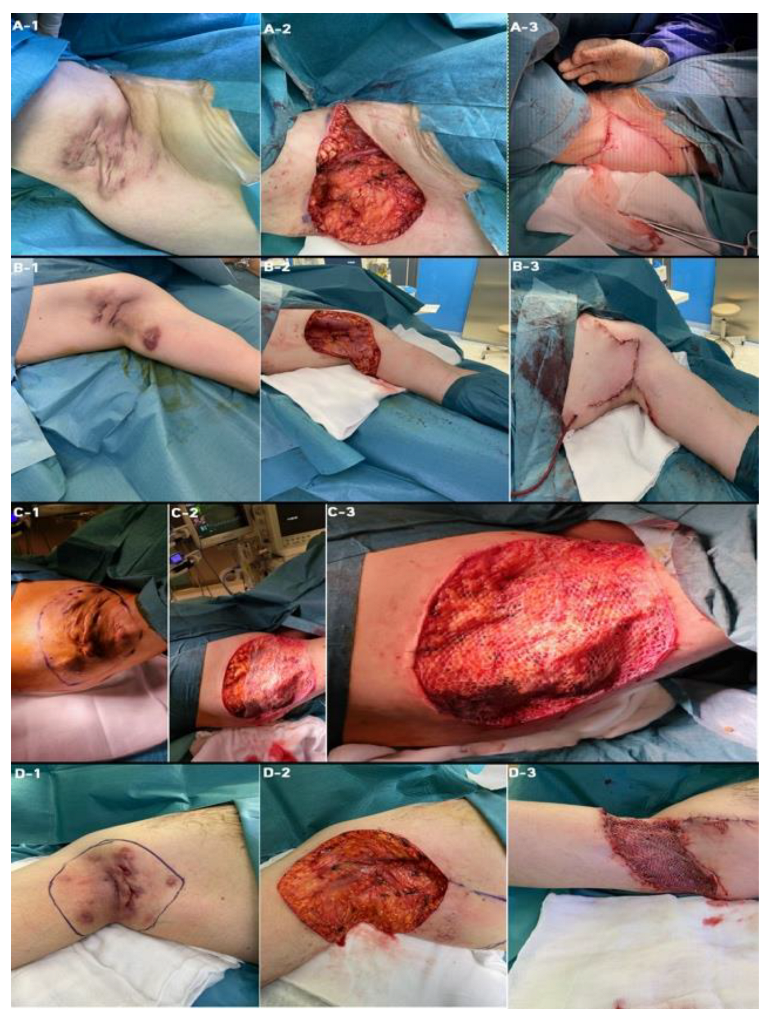

3.2. Types of Surgical Interventions

3.3. Health-Related Life Quality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zouboulis, C.C.; Desai, N.; Emtestam, L.; Hunger, R.E.; Ioannides, D.; Juhász, I.; Lapins, J.; Matusiak, L.; Prens, E.P.; Revuz, J.; et al. European S1 guideline for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2015, 29, 619–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marasca, C.; Tranchini, P.; Marino, V.; Annunziata, M.C.; Napolitano, M.; Fattore, D.; Fabbrocini, G. The pharmacology of antibiotic therapy in hidradenitis suppurativa. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020, 13, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scala, E.; Cacciapuoti, S.; Garzorz-Stark, N.; Megna, M.; Marasca, C.; Seiringer, P.; Volz, T.; Eyerich, K.; Fabbrocini, G. Hidradenitis Suppurativa: Where We Are and Where We Are Going. Cells 2021, 10, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldburg, S.R.; Strober, B.E.; Payette, M.J. Hidradenitis suppurativa: Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, 1045–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.V.; Damiani, G.; Orenstein, L.; Hamzavi, I.; Jemec, G.B. Hidradenitis suppurativa: An update on epidemiology, phenotypes, diagnosis, pathogenesis, comorbidities and quality of life. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2021, 35, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalgard, F.J.; Gieler, U.; Tomas-Aragones, L.; Lien, L.; Poot, F.; Jemec, G.; Misery, L.; Szabo, C.; Linder, D.; Sampogna, F.; et al. The psychological burden of skin diseases: A cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- von der Werth, J.M.; Jemec, G.B. Morbidity in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br. J. Dermatol. 2001, 144, 809–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matusiak, L.; Bieniek, A.; Szepietowski, J.C. Psychophysical aspects of hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2010, 90, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thorlacius, L.; Cohen, A.D.; Gislason, G.H.; Jemec, G.; Egeberg, A. Increased Suicide Risk in Patients with Hidradenitis Suppurativa. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vazquez, B.G.; Alikhan, A.; Weaver, A.L.; Wetter, D.A.; Davis, M.D. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: A population-based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matusiak, Ł.; Bieniek, A.; Szepietowski, J.C. Hidradenitis suppurativa markedly decreases quality of life and professional activity. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2001, 62, 706–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theut Riis, P.; Thorlacius, L.; Knudsen List, E.; Jemec, G. A pilot study of unemployment in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa in Denmark. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 176, 1083–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condamina, M.; Penso, L.; Tran, V.T.; Hotz, C.; Guillem, P.; Villani, A.P.; Perrot, P.; Bru, M.F.; Jacquet, E.; Nassif, A.; et al. Baseline Characteristics of a National French E-Cohort of Hidradenitis Suppurativa in Compare and Comparison with Other Large Hidradenitis Suppurativa Cohorts. Dermatology 2021, 237, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canoui-Poitrine, F.; Le Thuaut, A.; Revuz, J.E.; Viallette, C.; Gabison, G.; Poli, F.; Pouget, F.; Wolkenstein, P.; Bastuji-Garin, S. Identification of three hidradenitis suppurativa phenotypes: Latent class analysis of a cross-sectional study. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 1506–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gierek, M.; Ochała-Gierek, G.; Kitala, D.; Łabuś, W.; Bergler-Czop, B. Surgical management of hidradenitis suppurativa. Adv. Dermatol. Allergol. 2022, 15, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouboulis, C.C.; Bechara, F.G.; Dickinson-Blok, J.L.; Gulliver, W.; Horváth, B.; Hughes, R.; Kimball, A.B.; Kirby, B.; Martorell, A.; Podda, M.; et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: A practical framework for treatment optimization—systematic review and recommendations from the HS ALLIANCE working group. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, W.; Zouboulis, C.C.; Prens, E.; Jemec, G.B.; Tzellos, T. Evidence-based approach to the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa, based on the European guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2016, 17, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Folkes, A.S.; Hawatmeh, F.Z.; Wong, A.; Kerdel, F.A. Emerging drugs for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 2020, 25, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiss, N.; Plázár, D.; Lőrincz, K.; Bánvölgyi, A.; Valent, S.; Wikonkál, N. A hidradenitis suppurativa nőgyógyászati vonatkozásai [Gynecological aspects of hidradenitis suppurativa]. Orv. Hetil. 2019, 160, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger, U.M.; Erba, P.; Pierer, G.; Kalbermatten, D.F. Hidradenitis suppurativa of the groin treated by radical excision and defect closure by medial thigh lift: Aesthetic surgery meets reconstructive surgery. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. JPRAS 2009, 62, 1355–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alikhan, A.; Sayed, C.; Alavi, A.; Alhusayen, R.; Brassard, A.; Burkhart, C.; Crowell, K.; Eisen, D.B.; Gottlieb, A.B.; Hamzavi, I.; et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: A publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: Part I: Diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 81, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kouris, A.; Platsidaki, E.; Christodoulou, C.; Efstathiou, V.; Dessinioti, C.; Tzanetakou, V.; Korkoliakou, P.; Zisimou, C.; Antoniou, C.; Kontochristopoulos, G. Quality of Life and Psychosocial Implications in Patients with Hidradenitis Suppurativa. Dermatology 2016, 232, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavon Blanco, A.; Turner, M.A.; Petrof, G.; Weinman, J. To what extent do disease severity and illness perceptions explain depression, anxiety and quality of life in hidradenitis suppurativa? Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 180, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjaersgaard Andersen, R.; Theut Riis, P.; Jemec, G. Factors predicting the self-evaluated health of hidradenitis suppurativa patients recruited from an outpatient clinic. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2018, 32, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimstad, Ø.; Tzellos, T.; Dufour, D.N.; Bremnes, Ø.; Skoie, I.M.; Snekvik, I.; Jarnaess, E.; Kyrgidis AIngvarsson, G. Evaluation of medical and surgical treatments for hidradenitis suppurativa using real-life data from the Scandinavian registry (HISREG). J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2019, 33, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibrila, J.; Chaput, B.; Boissière, F.; Atlan, M.; Fluieraru, S.; Bekara, F.; Herlin, C. Traitement radical de la maladie de Verneuil: Comparaison de l’utilisation du derme artificiel et des lambeaux perforants pédiculés [Radical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: Comparison of the use of the artificial dermis and pedicled perforator flaps]. Ann. Chir. Plast. Esthet. 2018, 64, 224–236. [Google Scholar]

- Marchesi, A.; Amendola, F.; Garieri, P.; Steinberger, Z.; Vaienti, L. Wide Local Excisions and Pedicled Perforator Flaps in Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Study of Quality of Life. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2021, 86, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | ||

|---|---|---|

| General | n (%) | 21 (100.00) |

| Age, median (±QD) | 38.00 (10.00) | |

| Males, n (%) | 10 (47.61) | |

| Females, n (%) | 11 (52.38) | |

| BMI, median (±QD) | 33.00 (2.85) | |

| HS | Hurley stage of disease, n (%) | |

| - I | 5 (23.80) | |

| - II | 3 (14.28) | |

| - III | 13 (61.90) | |

| iHS4 score | ||

| - Mild (≤3 points) | 5 (23.80) | |

| - Moderate (4–10 points) | 3 (14.28) | |

| - Severe (≥11 points) | 13 (61.90) | |

| Location of HS, n (%) | ||

| - armpit | 15 (71.43) | |

| - groin | 3 (14.29) | |

| - buttocks | 1 (4.76) | |

| - vulva | 1 (4.76) | |

| - scrotum | 1 (4.76) | |

| Time from first symptoms to final diagnosis in years, median (± QD) | 8.00 (5.00) | |

| Duration of disease in years, median (± QD) | 10.00 (4.50) | |

| Intervention | Type of intervention, n (%) | |

| - rotatory flap | 17 (80.95) | |

| - STSG | 2 (9.52) | |

| - rotatory flap + STSG | 1 (4.76) | |

| - debridement + VAC + STSG | 1 (4.76) | |

| Time of hospitalization in days, median (± QD) | 5.00 (2.00) | |

| 6-month follow-up | Wound healed completely, n (%) | 17 (80.95) |

| Keloid, n (%) | 2 (9.52) | |

| Wound healed completely with HS recurrence, n (%) | 1 (4.76) | |

| Wound during healing process, n (%) | 1 (4.76) | |

| Comorbidities | Diabetes mellitus | 3 (14.29) |

| Metabolic syndrome | 4 (19.05) | |

| Hypertension | 9 (42.86) |

| Characteristic | Median ± QD | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hurley Stage of HS | Kruskal–Wallis | I vs. II | I vs. III | II vs. III | |||

| I | II | III | |||||

| EQ-5D-5L before, points | 40.00 ± 20.00 | 60.00 ± 0.00 | 50.00 ± 10.00 | 0.024 | 0.031 | 1.000 | 0.059 |

| EQ-5D-5L after, points | 100.00 ± 10.00 | 100.00 ± 0.50 | 90.00 ± 5.00 | 0.208 | - | - | - |

| BMI | 26.60 ± 4.35 | 33.50 ± 1.15 | 30.80 ± 1.80 | 0.085 | - | - | - |

| Age, years | 22.00 ± 0.50 | 45.00 ± 4.50 | 42.00 ± 2.00 | 0.033 | 0.068 | 0.076 | 1.000 |

| Time from first symptoms to final diagnosis, years | 1.00 ± 0.50 | 15.00 ± 2.00 | 12.00 ± 4.00 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.014 | 0.296 |

| Time of hospitalization, days | 4.00 ± 1.00 | 4.00 ± 1.00 | 7.00 ± 1.50 | 0.014 | 1.000 | 0.023 | 0.306 |

| Duration of disease, years | 4.00 ± 1.50 | 16.00 ± 2.50 | 14.00 ± 4.50 | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.026 | 0.737 |

| Variables | EQ-5D-5L Before | EQ-5D-5L After | BMI | Age | From First Symptoms to Final Diagnosis | Time of Hospitalization | Duration of Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | |||||||

| EQ-5D-5L before | - | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.41 | 0.55 * | 0.05 | 0.43 |

| EQ-5D-5L after | 0.31 | - | 0.10 | −0.21 | 0.03 | −0.42 | −0.05 |

| Stage I patients | |||||||

| EQ-5D-5L before | - | −0.44 | −0.63 | 0.89 * | −0.89 * | 0.66 | −0.79 |

| EQ-5D-5L after | −0.44 | - | 0.59 | −0.67 | 0.67 | −0.89 * | 0.89 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gierek, M.; Kitala, D.; Łabuś, W.; Szyluk, K.; Niemiec, P.; Ochała-Gierek, G. Impact of Hidradenitis Suppurativa Surgical Treatment on Health-Related Life Quality. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4327. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11154327

Gierek M, Kitala D, Łabuś W, Szyluk K, Niemiec P, Ochała-Gierek G. Impact of Hidradenitis Suppurativa Surgical Treatment on Health-Related Life Quality. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(15):4327. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11154327

Chicago/Turabian StyleGierek, Marcin, Diana Kitala, Wojciech Łabuś, Karol Szyluk, Paweł Niemiec, and Gabriela Ochała-Gierek. 2022. "Impact of Hidradenitis Suppurativa Surgical Treatment on Health-Related Life Quality" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 15: 4327. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11154327

APA StyleGierek, M., Kitala, D., Łabuś, W., Szyluk, K., Niemiec, P., & Ochała-Gierek, G. (2022). Impact of Hidradenitis Suppurativa Surgical Treatment on Health-Related Life Quality. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(15), 4327. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11154327