Questionnaire Survey on Driving among Patients with Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

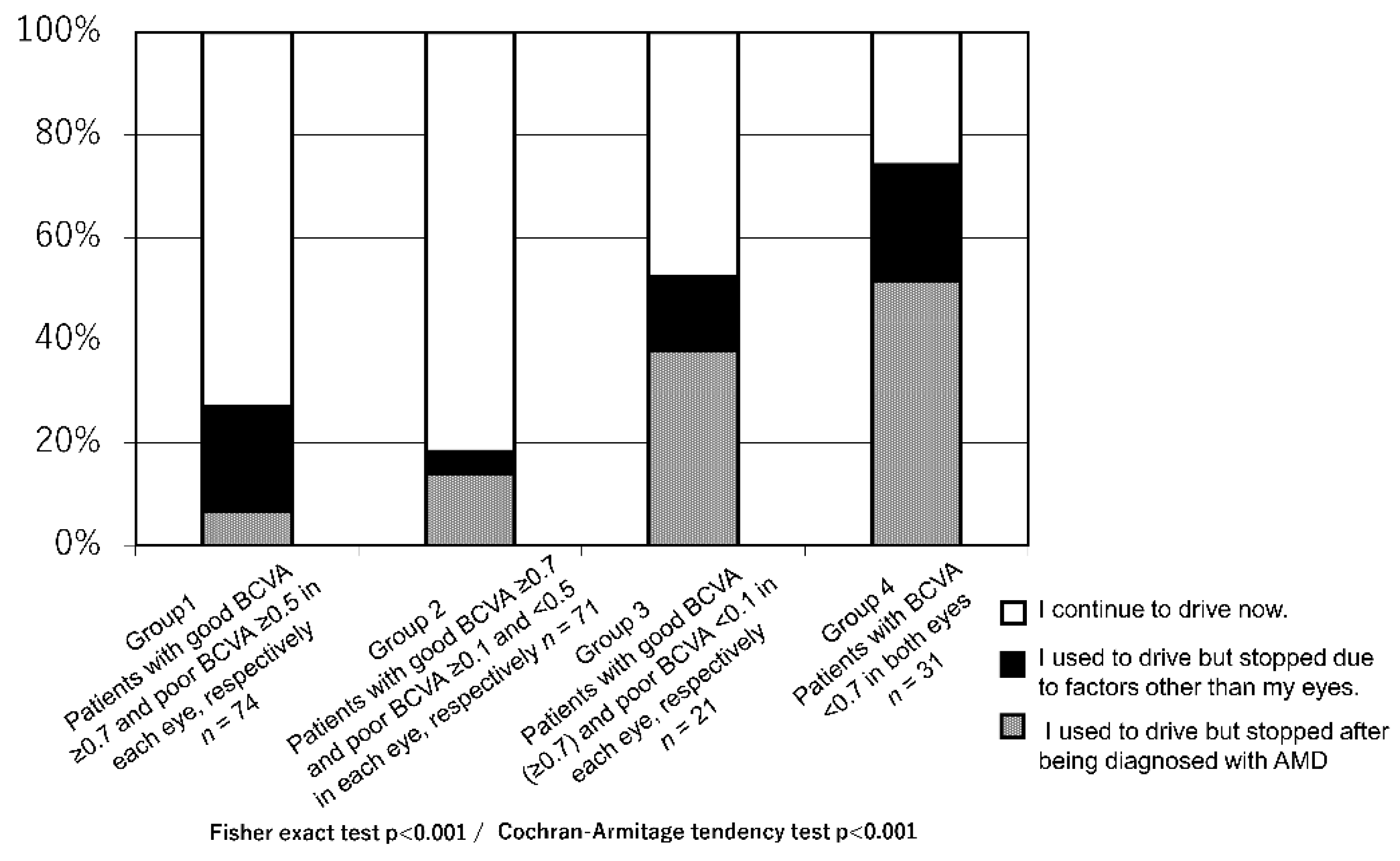

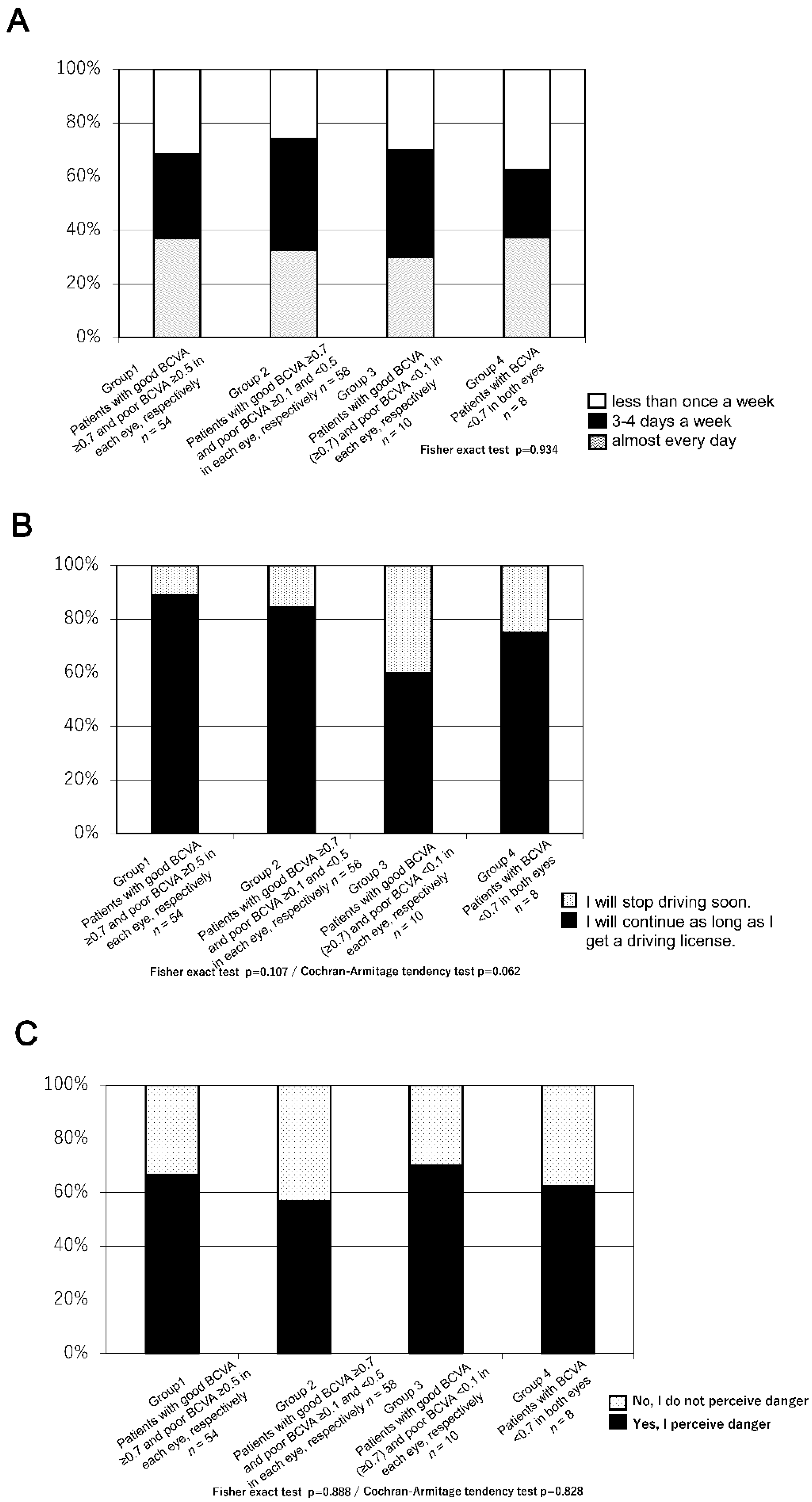

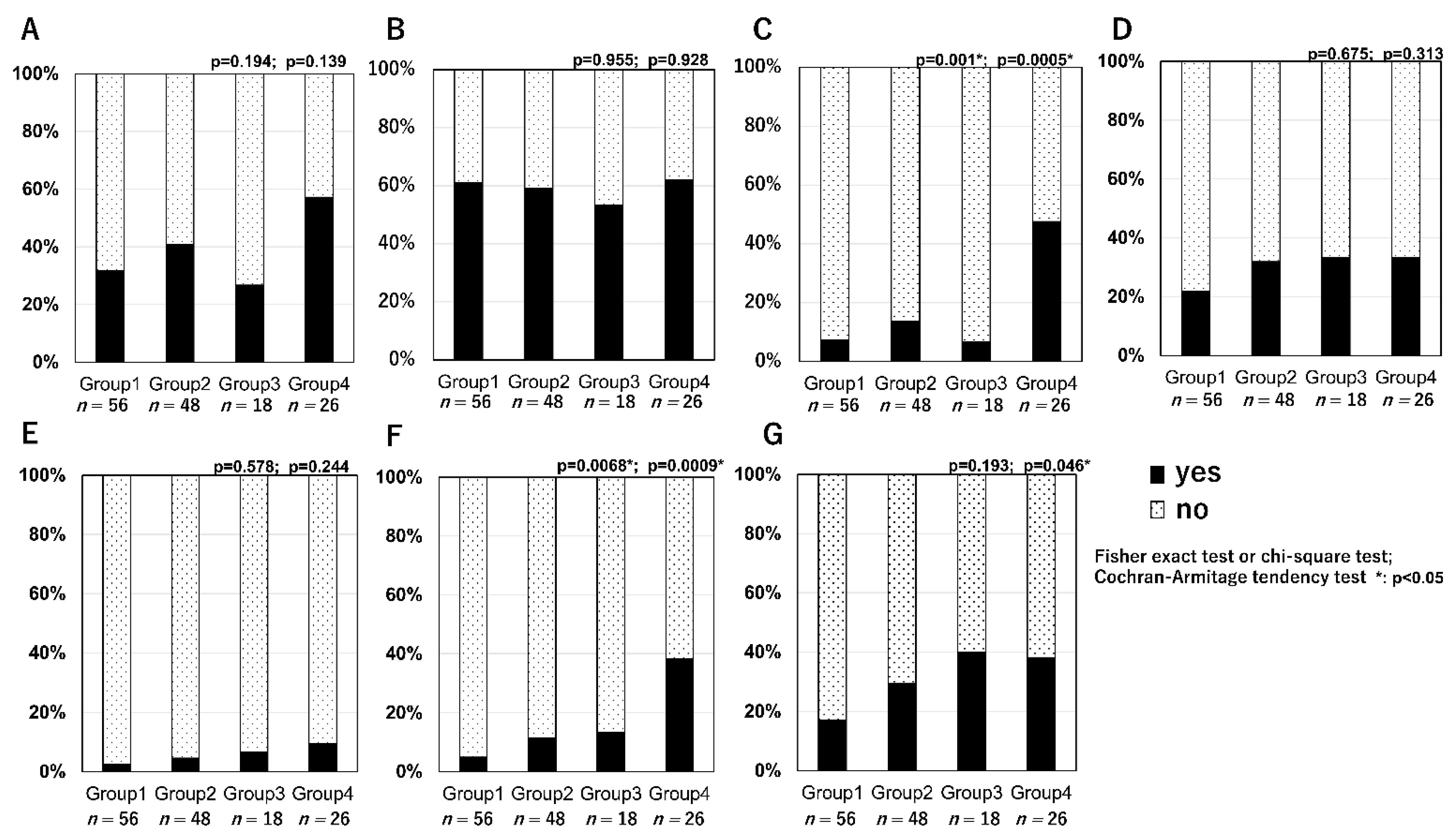

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mitchell, P.; Smith, W.; Attebo, K.; Wang, J.J. Prevalence of age-related maculopathy in Australia: The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology 1995, 102, 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, T.; Klie, F. The incidence of registered blindness caused by age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 1996, 74, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuzawa, M.; Tamakoshi, A.; Kawamura, T.; Ohno, Y.; Uyama, M.; Honda, T. Report on the nationwide epidemiological survey of exudative age-related macular degeneration in Japan. Int. Ophthalmol. 1997, 21, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, L.J. Age-related macular degeneration: The current understanding of the status of clinicopathology, diagnosis and management. J. Am. Optom. Assoc. 1993, 64, 822–837. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- The International ARM Epidemiological Study Group. An international classification and grading system for age-related maculopathy and age-related macular degeneration. Surv. Ophthalmol. 1995, 39, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Garner, L.F. Effects of Luminance on Contrast Sensitivity in Senile Macular Degeneration. Optom. Vis. Sci. 1983, 60, 788–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Zadnik, K.; Bailey, I.L. Effect of Luminance, Contrast, and Eccentricity on Visual Acuity in Senile Macular Degeneration. Optom. Vis. Sci. 1984, 61, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleiner, R.C.; Enger, C.; Alexander, M.F.; Fine, S.L. Contrast Sensitivity in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1988, 106, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressler, N.M.; Chang, T.S.; Varma, R.; Suñer, I.; Lee, P.; Dolan, C.M.; Fine, J. Driving ability reported by neovascular age-related macular degeneration after treatment with ranibizumab. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E.; Muñoz, B.; West, S.K.; Jampel, H.D.; Friedman, D.S. Glaucoma and Quality of Life: The Salisbury Eye Evaluation. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D.S.; Freeman, E.; Munoz, B.; Jampel, H.D.; West, S.K. Glaucoma and mobility performance: The Salisbury Eye Evaluation Project. Ophthalmology 2007, 114, 2232–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coeckelbergh, T.R.; Brouwer, W.H.; Cornelissen, F.W.; Van Wolffelaar, P.; Kooijman, A.C. The effect of visual field defects on driving performance: A driving simulator study. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2002, 120, 1509–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keay, L.; Jasti, S.; Munoz, B.; Turano, K.A.; Munro, C.A.; Duncan, D.D.; Baldwin, K.; Bandeen-Roche, K.J.; Gower, E.W.; West, S.K. Urban and rural differences in older drivers’ failure to stop at stop signs. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2009, 41, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, S.; Yuki, K.; Ozeki, N.; Shiba, D.; Abe, T.; Kouyama, K.; Tsubota, K. The Association between Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma and Motor Vehicle Collisions. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 4177–4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGwin, G., Jr.; Xie, A.; Mays, A.; Joiner, W.; DeCarlo, D.K.; Hall, T.A. Visual field defects and the risk of motor vehicle collisions among patients with glaucoma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005, 46, 4437–4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishman, G.A.; Anderson, R.J.; Stinson, L.; Haque, A. Driving performance of retinitis pigmentosa patients. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1981, 65, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlyk, J.P.; Alexander, K.R.; Severing, K.; Fishman, G.A. Assessment of driving performance in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1992, 110, 1709–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owsley, C.; Stalvey, B.T.; Wells, J.; Sloane, M.E.; McGwin, G. Visual Risk Factors for Crash Involvement in Older Drivers With Cataract. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2001, 119, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitta, L.; Quintas, J.; Trindade, I.; Belchior, P.; Gameiro, K. Older drivers are at increased risk of fetal crash involvement: Results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 95, 104414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owsley, C.; McGwin, G.; Searcey, K. A Population-Based Examination of the Visual and Ophthalmological Characteristics of Licensed Drivers Aged 70 and Older. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Boil. Sci. Med. Sci. 2012, 68, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cruess, A.; Zlateva, G.; Xu, X.; Rochon, S. Burden of illness of neovascular age-related macular degeneration in Canada. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 42, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.E.; Lovie-Kitchin, J.E.; Woods, R.L. Vision and mobility performance of subjects with age-related macular degeneration. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2002, 79, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, J.M.; Lacherez, P.F.; Black, A.A.; Cole, M.H.; Boon, M.Y.; Kerr, G.K. Postural Stability and Gait among Older Adults with Age-Related Maculopathy. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlyk, J.P.; Pizzimenti, C.E.; Fishman, G.A.; Kelsch, R.; Wetzel, L.C.; Kagan, S.; Ho, K. A comparison of driving in older subjects with and without age-related macular degeneration. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1995, 113, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruko, I.; Iida, T.; Saito, M.; Nagayama, D.; Saito, K. Clinical Characteristics of Exudative Age-related Macular Degeneration in Japanese Patients. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 144, 15–22.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselius, N.J.F.; Brynskov, T.; Falk, M.K.; Sørensen, T.L.; Subhi, Y. Driving vision in patients with neovascular AMD in anti-VEGF treatment. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Q1, Have you driven? A, yes; B, no |

| Q2, If the answer for Q1 is B (no), please choose one of the following: (A) I used to drive but stopped after being diagnosed with AMD. (B) I used to drive but stopped due to factors other than my eyes. (C) I have never driven |

| Q3, For individuals who answered A (yes) at Q1. Q1, How often do you drive? (A) almost every day; (B) 3–4 days a week; (C) less than once a week Q2, Will you continue to drive? (A) I will continue as long as I get a driving license; (B) I will stop driving soon Q3, Have you ever felt in danger while driving? (A) yes, I perceive danger; (B) no, I do not perceive danger. |

| Q4, For individuals who used to drive and have now stopped (answered A or B at Q2), as well as those who perceived danger when driving (answered A at Q3). Which situation have you felt in danger while driving? (multiple answers allowed) (1) failing to notice pedestrians, oncoming vehicles, and signs (2) when driving at night (blur or glare) (3) discrimination of the signal colour (4) when parking (5) when changing lanes (6) when determining the vehicle spacing (7) understanding the surroundings (8) others |

| Patients (n) | Years (Mean ± SD) | Eyes with Bilateral Pseudophakia: with Unilateral Pseudophakia with Another Phakia: with Bilateral Phakic Eye: (Ratio of Psedophakia) | Eyes with AMD Bilateral: Unilateral (Ratio of Binocular Cases) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

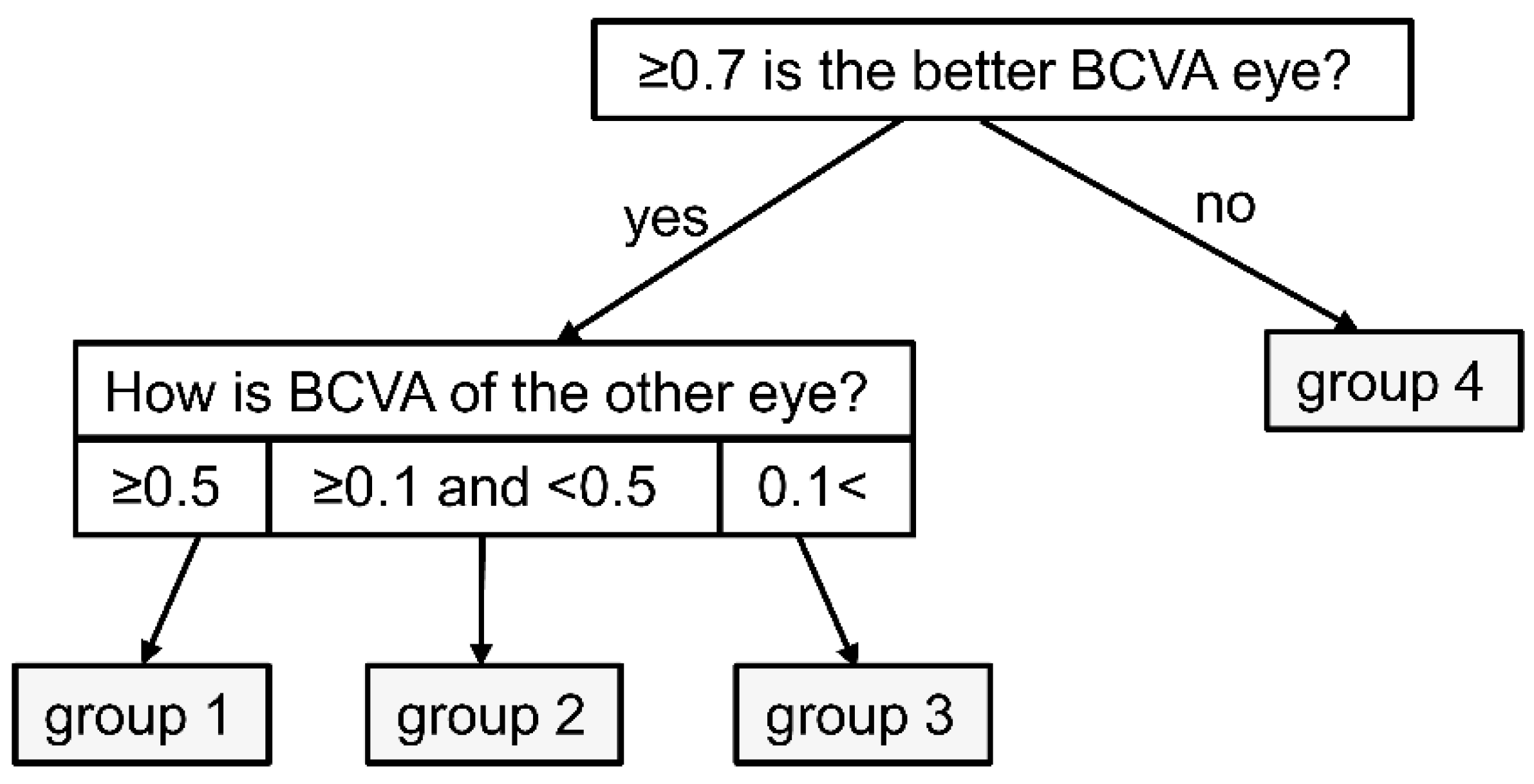

| Group 1 (Patients with good BCVA (≥0.7) and poor BCVA (≥0.5) in each eye, respectively) | 74 | 74.1 ± 7.6 | 13:5:56 (20.9%) | 2:72 (2.7%) |

| Group 2 (Patients with good BCVA (≥0.7) and poor BCVA (≥0.1 and <0.5) in each eye, respectively) | 71 | 72.9 ± 6.3 | 12:5:54 (20.5%) | 15:56 (21.1%) |

| Group 3 (Patients with good BCVA (≥0.7) and poor BCVA (<0.1) in each eye, respectively) | 21 | 77.3 ± 6.1 | 6:1:14 (31.0%) | 7:14 (33.3%) |

| Group 4 (Patients with BCVA < 0.7 in both eyes) | 31 | 78.9 ± 6.8 | 17:0:14 (54.8%) | 26:5 (83.9%) |

| p-value | p = 0.001 * | p = 0.047 * | p < 0.0001 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hara, C.; Sawa, M.; Gomi, F.; Nishida, K. Questionnaire Survey on Driving among Patients with Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Japan. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4845. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10214845

Hara C, Sawa M, Gomi F, Nishida K. Questionnaire Survey on Driving among Patients with Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Japan. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(21):4845. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10214845

Chicago/Turabian StyleHara, Chikako, Miki Sawa, Fumi Gomi, and Kohji Nishida. 2021. "Questionnaire Survey on Driving among Patients with Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Japan" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 21: 4845. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10214845

APA StyleHara, C., Sawa, M., Gomi, F., & Nishida, K. (2021). Questionnaire Survey on Driving among Patients with Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Japan. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(21), 4845. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10214845