Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is one of the fastest-growing major causes of death internationally. Better treatment of CKD and its complications is crucial to reverse this negative trend. Anemia is a frequent complication of CKD and is associated with unfavorable clinical outcomes. It is a devastating complication of progressive kidney disease, that negatively affects also the quality of life. The prevalence of anemia increases in parallel with CKD progression. The aim of this review is to summarize the current knowledge on therapy of renal anemia. Iron therapy, blood transfusions, and erythropoietin stimulating agents are still the mainstay of renal anemia treatment. There are several novel agents on the horizon that might provide therapeutic opportunities in CKD. The potential therapeutic options target the hepcidin–ferroportin axis, which is the master regulator of iron homeostasis, and the BMP-SMAD pathway, which regulates hepcidin expression in the liver. An inhibition of prolyl hydroxylase is a new therapeutic option becoming available for the treatment of anemia in CKD patients. This new class of drugs stimulates the synthesis of endogenous erythropoietin and increases iron availability. We also summarized the effects of prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors on iron parameters, including hepcidin, as their action on the hematological parameters. They could be of particular interest in the out-patient population with CKD and patients with ESA hyporesponsiveness. However, current knowledge is limited and still awaits clinical validation. One should be aware of the potential risks and benefits of novel, sophisticated therapies.

1. Introduction

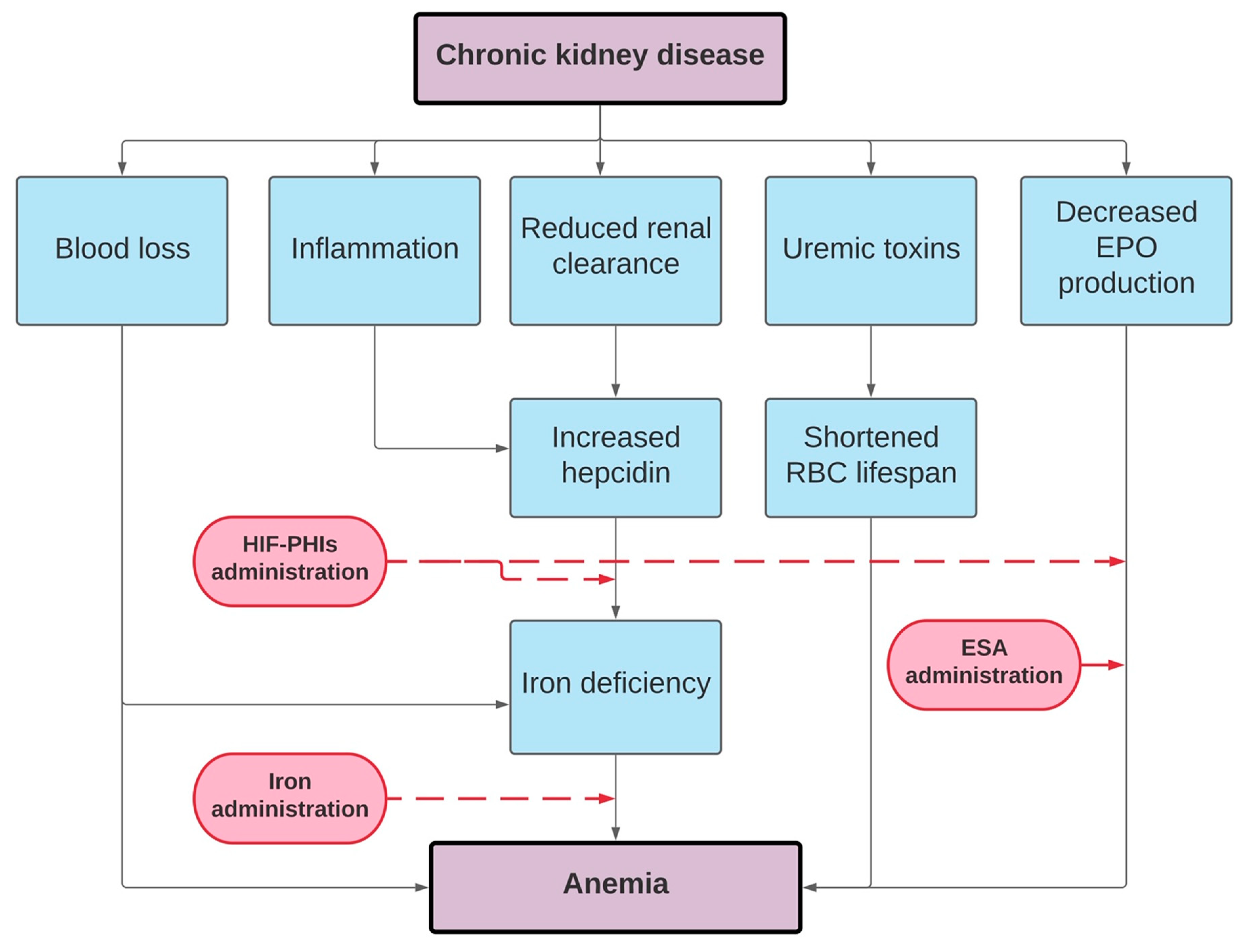

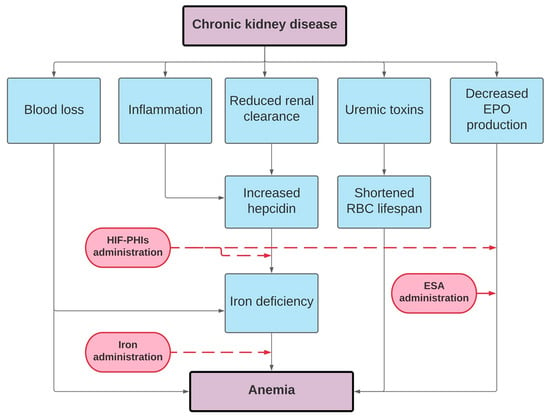

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is one of the fastest-rising major causes of death internationally, with a global prevalence of 13% [1]. Better treatment of CKD and its complications is crucial to reverse this negative trend. Anemia is a frequent complication of CKD and is associated with unfavorable clinical outcomes [2,3]. The prevalence of renal anemia gradually rises as the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decreases [3]. Anemia occurs in approximately half of patients with CKD stage G4 and in more than 90% of the end-stage renal disease patients who undergo dialysis [3,4,5]. Correcting renal anemia can decrease mortality, hospitalization, risk of CKD progression, and improve the health-related quality of life [5,6,7,8,9,10]. The principial mechanism implicated in the development of renal anemia is a combination of inadequate erythropoietin (EPO) synthesis and EPO resistance [11,12]. Other contributing factors include both absolute and functional iron deficiency, chronic inflammation, uremic toxins, disturbed iron homeostasis, shortened red blood cell (RBC) life span, and vitamin deficiencies (vitamin B12 or folic acid) [11,13]. Moreover, hemodialysis itself may contribute to blood loss and damage to RBCs [14]. Screening for and treating anemia is a routine part of the care of CKD patients [15].

At the beginning of the second half of the 20th century, Erslev recognized that plasma from anemic rabbits containing a factor capable of stimulating erythropoiesis could be potentially used as a therapeutic agent [16]. In 1957, researchers revealed that this erythropoietic factor is produced by the kidney [17]. Two decades later, this substance was isolated from urine collected from patients with aplastic anemia and named erythropoietin [18]. Thanks to the advances in biotechnology, the EPO gene was successfully isolated and cloned [19]. This discovery paved the way for the next breakthrough—the development of the recombinant human erythropoietin. The ability to stimulate erythropoiesis with therapeutic agents became a milestone that probably was the greatest breakthrough in nephrology. Before effective treatment for anemia was available, a high proportion of HD patients required regular high-volume blood transfusions with attendant risks of immunological sensitization, iron overload, and viral infections. It should be mentioned that the effects of the blood transfusions were transient, and many patients required chronic repeated transfusional support to alleviate or relieve debilitating symptoms such as exertional shortness of breath, lethargy, and poor physical capacity.

2. Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents

Before effective treatment for renal anemia became available, a high proportion of hemodialysis patients required blood transfusions with the attendant risks of immunological sensitization, iron overload, and viral infections. Currently, injectable erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) with adjuvant iron therapy and/or RBC transfusions represent the mainstay of anemia’s treatment in CKD [20]. ESAs are used for the treatment of CKD anemia that cannot be corrected by iron supplementation alone. The term ESA encompasses short-acting recombinant human erythropoietin (epoetin), medium-acting darbepoetin alfa, long-acting epoetin beta pegol, and their biosimilars [21]. ESAs are characterized by a common mechanism of action but different pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties [22]. Despite the widespread use of ESAs to treat anemia in CKD, the relative and mortality risks associated with using different types of ESAs still have not been fully elucidated [23]. Sakaguchi et al. concluded that long-acting ESAs might be associated with a higher risk of death among patients undergoing hemodialysis than short-acting ESAs [23]. However, other studies did not confirm these findings [22]. To date, biosimilars have demonstrated comparable safety and effectiveness relative to originator ESAs [24,25]. The selection of the individual therapy depends on the severity of anemia and iron deficiency.

The development of ESAs has changed the treatment of renal anemia dramatically; however, some concerns have remained, particularly in regard to cardiovascular complications and malignancy. Randomized controlled trials such as CHOIR [26] or CREATE [27] showed that targeting Hb to normal ranges in CKD patients or on HD (Normal Hematocrit Trial) [28] could be harmful and should be avoided. It has led to decreases in achieved Hb levels and increases in RBC transfusions. Furthermore, ESAs hyporesponsiveness and functional iron deficiency represent new clinical concerns to solve. Based on the results of the TREAT trial [29] KDIGO [30] recommended lowering Hb targets in patients with CKD. Data from US Renal Data System (USRDS) and Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) showed clearly that the use of iv iron and blood transfusions increased while the use of ESAs declined [31,32,33]. At present, there are no well-defined guidelines regarding when to initiate ESA treatment in CKD patients.

The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2012 guidelines recommend starting an ESA on an individual basis [30]. ESAs are administered to most hemodialysis patients with hemoglobin (Hb) <10 g/dL and are not iron deficient [34]. Similarly, KIDIGO anemia guidelines do not indicate a recommended starting dose but state that it should be individualized [30]. The dose of ESA required to reach target Hb varies widely among patients [34]. Generally, the dose is adjusted monthly in response to the Hb (the increase should be in the range of 1–2 g/dL per month) [35]. Either intravenous (iv) or subcutaneous (sc) ESA administration may be used. Several studies suggested that the sc dose of ESA required to achieve a target Hb is approximately 30 percent less than that required with IV administration [25]. SC ESA administration is characterized by slower absorption compared to iv administration, resulting in an extended terminal half-life [36]. In patients receiving ESA, the general Hb target should be individualized to 10–12 g/dL, based upon patient clinical characteristics, symptoms, and preferences. The ESAs effectively increase Hb concentration and improve patients’ quality of life [37,38]. ESAs also act as hepcidin suppressors by inducing erythroferrone (ERFE). Hepcidin, a small polypeptide synthesized by the liver, plays a central role in regulating iron homeostasis by promoting ferroportin’s internalization and degradation, the only known cellular iron exporter [39]. As an effect of hepcidin, extracellular iron decreases via decreased intestinal absorption and iron mobilization from the reticuloendothelial system’s macrophages. Hepcidin levels are frequently elevated in patients with CKD due to inflammatory state, impaired renal clearance, and iron supplementation, contributing to functional iron deficiency and interfering hematopoiesis [37].

There is some evidence that in the case of inflammation (which increases hepcidin) and iron deficiency (which decreases hepcidin), the latter is predominant. This is frequently the case for anemia in CKD. The study of Theurl et al. [40] compared the levels of hepcidin in patients with anemia of chronic disease (ACD), those with iron-deficiency anemia (IDA) or mixed ACD/IDA: hepcidin was increased in patients with ACD compared to control subjects, but in mixed ACD/IDA patients, hepcidin levels were comparable to those observed in IDA patients [41,42].

However, patients treated with ESAs are exposed to supraphysiologic EPO concentrations, potentially leading to adverse events [5,37,43,44]. Some studies have found an increased risk of cardiovascular events and stroke in both hemodialysis-dependent and nonhemodialysis-dependent patients targeted at higher Hb levels [45,46]. Adverse events seem to be related to a high ESA dose rather than with a high Hb target. In this sense, Choukroun et al. [47] in their prospective study showed that a target hemoglobin ≥13 g/dL reduced the progression of chronic allograft nephropathy in kidney transplant recipients without an increase in adverse events. Other adverse effects of ESAs include the development or worsening of hypertension, venous thromboembolism including hemodialysis access, malignancy, and an even greater risk of death [48].

Most of the adverse effects occur when ESAs are used to maintain normal or near-normal Hb as reviewed elegantly by Locatelli et al. [49]. On the other hand, the risk of hypertension appears to be independent of target Hb [50]. Multiple patient safety concerns regarding ESAs therapy safety resulted in a decrease in target Hb. Furthermore, hyporesponsiveness affecting 10% of patients with CKD represents another major clinical challenge in ESAs therapy [51]. Hyporesponsiveness to ESA is defined as a continued need for greater than 300 IU/kg per week erythropoietin or 1.5 mg/kg per week darbepoetin administered SC [52]. Iron deficiency and chronic inflammation are the most important determinants of ESA resistance. In patients with ESA hyporesponsiveness, higher ESA doses are needed to raise Hb levels, likely increasing the risk of cardiovascular events and mortality [46,52]. The lowest ESA dose necessary to achieve the desired Hb level should be used, and excessively high doses in patients with ESA hyporesponsiveness should be avoided. The evidence shows that maintaining adequate iron stores is the most meaningful singular strategy for decreasing ESA requirements and for augmented ESA efficacy. Furthermore, a number of studies have underlined the shortcomings of ESA therapy related to convenience (e.g., mode of administration) [53]. Taken together, these downsides (adverse events, convenience, and hyporesponsiveness) suggest the need for the exploration of novel treatments of CKD anemia.

3. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Inhibitors

Concerns about ESA therapy are a major driver in searching for alternative therapeutic options. Hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors (HIF-PHIs) represent a novel approach to the treatment of anemia in patients with CKD [5,12,37,46,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. HIF-PHIs are oral drugs that mimic the natural response to hypoxia independent of cellular oxygen levels [54]. HIF-PHIs undergoing clinical trials include daprodustat, desidustat, enarodustat, molidustat, roxadustat, and vadadustat. Data on selected clinical trials regarding HIF-PHIs are gathered in Table 1 and Table 2 [46,53,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84]. HIF-PHIs have multiple targets of action, resulting in the stimulation of endogenous EPO production within the physiological range, suppression of liver hepcidin synthesis, and increased transcription of genes that promote iron utilization, which profoundly differentiates them from presently used ESAs [5,85].

Table 1.

HIF stabilizers—data on published peer-reviewed phase II studies in dialysis-dependent CKD and nondialysis-dependent CKD.

Table 2.

The main results of selected phase 3 studies of HIF-PIHs in CKD patients.

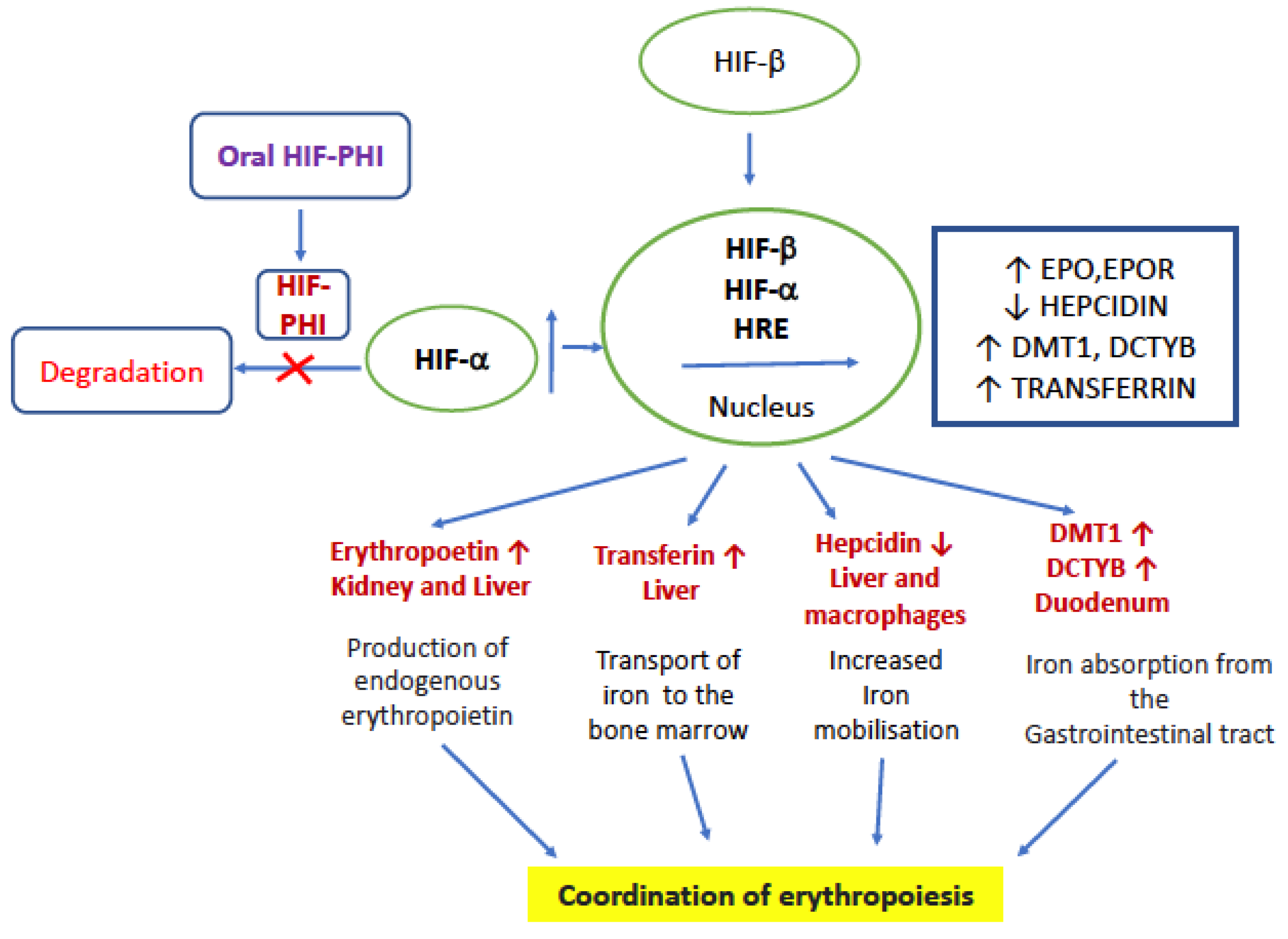

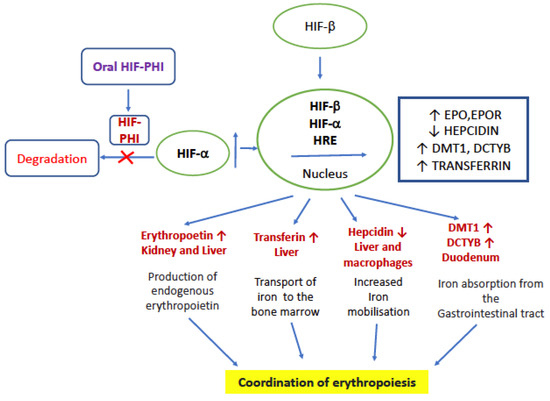

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) is the main transcription factor of hundreds of genes, including the EPO gene expressed in hypoxic tissues and adapted to a hypoxic environment [86]. HIF-PHIs are small molecules that inhibit the prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) proteins (PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3), which sense oxygen and control HIF activity [5,87]. HIF-PHIs by decreasing prolyl hydroxylase activity lead to the stabilization of HIF-α in the liver and kidney, resulting in upregulation of the endogenous EPO [46]. HIF is a heterodimer complex comprised of an oxygen-sensitive α-subunit (either HIF-1α, HIF-2α, or HIF-3α), which is rapidly degraded by PHD in the presence of oxygen, and a constitutively expressed β-subunit [71]. HIF-PHIs differ in molecular structure and likely have different levels of selectivity for the three main PHD isoforms [5]. Moreover, animal studies have shown that HIF also controls the expression of proteins playing a role in iron metabolism and utilization (upregulation of transferrin, soluble transferrin receptor 1 (sTfr1), ceruloplasmin, divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1), duodenal cytochrome b (Dcytb), and downregulation of hepcidin) [37,88]. It is widely accepted that EPO production and iron-regulating genes are mainly HIF-2α controlled, with HIF-1α playing a smaller role [5,88,89]. Increases in soluble transferrin receptor 1 improve iron availability, given its role as a carrier protein for transferrin required to import iron into the cell [53]. HIF-2α directly upregulates ferroportin and indirectly inhibits hepcidin expression promoting iron availability [52,90]. Supporting this notion, a meta-analysis performed by Wen et al. showed HIF-PHIs-related decreases in serum hepcidin and ferritin, together with increases in transferrin and TIBC, suggesting an improvement in iron utilization compared to the standard therapy with ESA and IV iron [37]. The administration of HIF-PHIs to patients with CKD was consistently associated with decreased plasma hepcidin levels in phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials [40,42,46,53,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84]. Researchers suggest that hepcidin suppression most likely results from the stimulation of erythropoiesis, as it seems that hepcidin is not a direct transcriptional target of HIF. There is no research report whether HIF can affect the expression of hepcidin gene, and there may be other mechanisms between HIF and hepcidin. Although ESAs were also reported to suppress hepcidin production through erythroferrone upregulation, Akizawa et al. observed a trend toward a decrease in hepcidin, following the switching from an ESA to enarodustat [46]. It is anticipated that the latter most likely results from differences in effectiveness in promoting erythropoiesis and EPO-mediated hepcidin regulators such as ERFE; however, future studies are needed to provide an answer.

All published phase II trials indicate that HIF-PHI therapy is at least as efficacious as conventional ESA therapy in managing Hb levels in both nondialysis-dependent CKD (ND-CKD and dialysis-dependent (DD-CKD) patients [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98]. The meta-analysis of 26 randomized controlled trials involving 2804 patients with CKD comparing the use of HIF-PHIs versus ESAs or placebo in the treatment of renal anemia found HIF-PHIs superior to placebo and at least as efficacious as classic ESAs in the short term [5]. Likewise, a meta-analysis by Qie et al., including 1010 patients, showed that roxadustat has a higher mean Hb level than placebo or EPO [91]. HIF-PHIs have demonstrated efficacy and safety in phase 2 and 3 trials in several different cohorts of CKD patients with anemia who are either ND-CKD or DD. Wang et al. reported that among the included HIF-PHIs, roxadustat was associated with a favored effect on Hb compared to classic ESAs [5]. Roxadustat administration leads to increases in endogenous EPO levels, with peak increases 8–12 h postdose in healthy volunteers and patients with CKD [61,62,63,64,65] With a half-life of 10 h, roxadustat is administered three times weekly [91]. HIF-PHIs such as roxadustat offer the promise of decreased inflammation, a better use of existing iron stores, and an enhanced gastrointestinal absorption of oral iron, along with an acceptable safety profile. In a European, multicenter, double-blind trial in a predialysis patient population, the safety profile of roxadustat was generally comparable with placebo [53]. Moreover, in roxadustat-treated patients, the markers of both iron (increased iron levels, increased transferrin levels, and total iron-binding capacity-TIBC, decreased hepcidin) and lipid (reduced low-density lipoprotein) metabolism were improved. It is suggested that the beneficial effect of roxadustat on lipid metabolism is primarily mediated by HIF-dependent effects on acetyl coenzyme A (required for cholesterol synthesis) and on the degradation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (a rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol synthesis). Roxadustat-related decreases in hepcidin and increases in soluble transferrin receptor levels have been observed in many studies [61,62,63,64,65]. In addition, recent phase 3 studies demonstrated that roxadustat was superior to placebo and noninferior to standard ESAs to treat CKD-related anemia [53,56,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81]. Patients who newly initiate dialysis require the highest doses of ESAs and have the greatest risk for mortality during the first year on dialysis.

Regarding safety, HIFs also activate, additionally to EPO, a large number of genes, which can also cause beneficial effects. Potential clinical benefits of HIF-PHIs therapy include: achieving Hb target with a 5–17-fold lower plasma EPO levels relative to those receiving ESA; and a lipid-lowering effect, blood-pressure reduction, anti-inflammatory effects, protection from ischemic injuries, and protective effects with regard to CKD [5,92,93,94,95,96,97,98]. Roxadustat and daprodustat are demonstrated to reduce triglyceride, total cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein levels [62,63,69,71]. In animal models, HIF-PHIs have been shown to lower blood pressure; however, clinical trials did not confirm this finding [46,53,56,58,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84]. A growing body of evidence suggests that HIF-PHIs increase Hb levels, with EPO levels remaining within the physiological range [46]. Studies in ND-CKD and DD-CKD patients showed that HIF-PHIs administration was associated with much lower plasma EPO increases than recombinant human EPO [71]. In addition, no accumulation of EPO was reported after a repeated dosing of enarodustat [32]. Since HIF transcription factors control or interact with many biologic processes, there is a concern about nonerythropoietic adverse effects. The areas of concern regarding HIF-PHIs include potential tumor-promoting effects, thrombosis, cardiovascular disease, and the progression of diabetic retinopathy [85,86,87,88,89]. To date, the most frequently reported AEs in undergoing clinical trials were gastrointestinal disorders (nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting) [5,12]. In short-term studies, no serious adverse events attributed to HIF-PHIs were observed, although the clinical prevalence of adverse events with long-term HIF-PHIs treatment needs to be determined. The occurrence of AEs is likely to depend on the pharmacokinetics and dosing of HIF-PHIs. For example, statistically significant rises in plasma vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) levels were observed when relatively high doses of daprodustat (50–100 mg) were given to healthy subjects but were not detected with lower doses sufficient to maintain Hb in CKD patients. Recently, Chertow et al. [96] reported that vadadustat, as compared with darbepoetin alfa, met the prespecified noninferiority criterion for hematologic efficacy but not the prespecified noninferiority criterion for cardiovascular safety in patients with ND-CKD, which was a composite of death from any cause, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke. On the other hand, Provenzano et al. [99] evaluated the efficacy and cardiovascular safety of roxadustat versus placebo by analyzing data pooled from three phase 3 studies of roxadustat in patients with nondialysis-dependent CKD and CKD-related anemia. They found that there were no increased risks of MACE (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.96 to 1.27), MACE + (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.94 to 1.21), all-cause mortality (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.93 to 1.26), or individual MACE+ components in patients treated with roxadustat versus those treated with placebo.

Taken together, HIF-PHIs can reduce the degradation of HIF irrespective of oxygen levels and decrease the production of hepcidin, thereby increasing the EPO level, utilization of iron, and stimulating the production of erythrocytes/hematopoiesis [5,37]. The mode of action is given in Figure 1. HIF-PHIs effectively decrease the need for iron replacement therapy and are effective in patients with ESA hyporesponsiveness caused by inflammation. Traditional ESAs for patients with ND-CKD require injection and medical visits, while HIF-PHIs have the advantage of oral administration. These benefits include convenience, simpler production, and pain avoidance.

Figure 1.

Mode of action of HIF-PHI. EPO—erythropoietin, EPOR—erythropoietin receptor, DCYTB, duodenal cytochrome B; DMT1, divalent metal transporter, HRE—hypoxia responsive element, and HIF—hypoxia inducible factor.

Roxadustat is approved in Japan and China. On 24 June 2021, the (CHMP) adopted a positive opinion, recommending the granting of a marketing authorization for the medicinal product Evrenzo, intended for the treatment of anemia symptoms in patients with chronic kidney disease (EMA/CHMP/341057/2021) [100]. However, on 15 July the Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee of the FDA voted against approval of roxadustat for the treatment of anemia due to chronic kidney disease for patients not on dialysis and on dialysis due to the higher portion of ND-CKD patients and DD-CKD patients experienced vascular access thrombosis compared with controls [101,102,103]. Table 3 summarizes the potential advantages and disadvantages of HIF inhibitors [5,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111].

Table 3.

Potential advantages and disadvantages of HIF-PHIs [5,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111].

4. Iron Supplementation

Good iron metabolism is essential for the efficacy of ESAs and HIF-PHIs [55]. Inflammation and iron depletion are the most important causes of hyporesponsiveness to ESA treatment [116]. Dysregulation of iron homeostasis in patients with CKD is multifactorial, including diminished renal clearance of hepcidin, inflammation, absolute iron deficiency, and functional iron deficiency [11,13]. Absolute iron deficiency is defined by severely decreased total iron stores. On the other hand, functional iron deficiency is a state of adequate iron stores but decreased iron availability for erythropoiesis [15,117,118]. A combination of both absolute and functional iron deficiency may also be present, suppressing erythropoiesis at the iron-dependent stage of Hb synthesis. Based on expert opinion, absolute iron deficiency is diagnosed when transferrin saturation (TSAT) is ≤20% and the serum ferritin concentration ≤ 100 ng/mL in nonhemodialysis patients and ≤200 ng/mL among hemodialysis patients [119,120]. Functional iron deficiency is characterized by TSAT ≤ 20% and elevated ferritin levels [119,120]. The KDIGO 2012 Anemia Guidelines recommend the regular monitoring of iron status (TSAT and ferritin at least every 3 months) during ESA therapy and before deciding to start or continue iron therapy [30]. Since iron deficiency plays an important role in anemia in CKD, iron agents are the mainstay of therapy for renal anemia. Iron therapy is introduced to replenish iron stores, increase Hb level to the desired level, and decrease needs for ESA. According to the guidelines, adult CKD patients with anemia or on ESA therapy should receive a trial of iv iron (or a 1–3 month trial of oral iron for ND-CKD patients) if an increase in Hb concentration or a decrease in ESA dose is desired and TSAT is <30% and ferritin is <500 µg/L [22]. The continuation of iron therapy should be based on an integrated assessment of Hb responses, iron status tests, ESA dose/responsiveness, ongoing blood losses, and clinical status, although the available data were considered insufficient for recommending long-term iv dosing strategies [30]. Carboxymaltose iron- FCM, isomaltoside iron, and ferumoxytol are among new iv iron preparations. Results from a prospective, multicentric, randomized controlled study of more than 2000 patients undergoing hemodialysis (HD) support the efficacy and safety of relatively high-dose iv iron therapy among hemodialysis-dependent patients treated with ESA [20,121]. Monthly administration of 400 mg iv iron in patients with serum ferritin < 700 µg/L and TSAT ≤ 40% decreases ESA use and lowers the risk of all-cause death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, and hospitalization for heart failure compared with iv iron administered in a reactive fashion for ferritin < 200 µg/L or TSAT < 20% [20,121]. FIND-CKD study in ND-CKD patients demonstrated that iv iron dosed to target ferritin of 400–600 µg/L compared with oral iron quickly reached and maintained Hb. Moreover, iv iron dosed to a target ferritin of 400–600 µg/L was superior to iv iron dosed to target ferritin of 100–200 µg/L for achieving a Hb increase of ≥ 1 g/dL [122]. The possible negative effects of iron compounds are still a matter of debate. Given its ability to participate in Fenton reaction, excessive iron supplementation may promote oxidative stress and potentially contribute to cardiovascular disease risk, CKD progression, and other organ damage in CKD patients [5,20]. In addition, iron is an essential trace metal for nearly all infectious microorganisms; thus, it has been hypothesized that excessive iron supplementation may lead to a permissive environment for infectious processes. Thus, the KDIGO workgroup recommends withholding iv iron during active infections [30].

Recently, a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies and randomized controlled trials in DD-CKD patients did not show any significant rise in cardiovascular events or infections in the group receiving a high dose of iron when compared to the low-dose group [123]. Likewise, a secondary analysis of PIVOTAL demonstrated that the risks of infections were similar between high-dose and low-dose iv iron groups [124]. However, a study by Li and colleagues showed that more intensive iv iron administration in HD-CKD patients is associated with a higher risk of mortality and infection-related events [125]. Whether high-dose-iron administration increases rates of infections or cardiovascular events in ND-CKD patients is still conflicting and remains to be studied. Considering the areas of uncertainty, caution is still warranted regarding more aggressive iv iron strategies in CKD patients, until more data are available. While there is general agreement that iv iron supplementation is the suitable method for DD-CKD patients, either iv or oral iron can be given to ND-CKD patients [20]. The KDIGO recommendation to use iv rather than oral iron in DD-CKD patients was supported by a number of clinical studies that demonstrated a greater Hb increase with iv iron than oral iron [30].

In addition, follow-up versions of iron sucrose have emerged to treat iron deficiency anemia, including renal anemia, in a number of countries worldwide. The assumption was that iron sucrose similar agents could be considered therapeutically equivalent to the originator iron sucrose. That said, Rottembourg et al. demonstrated that the switch from the originator iron sucrose to an iron sucrose similar agent resulted in destabilization of a well-controlled population of dialyzed patients and led to an increase in total anemia drug costs, putting a question mark on their equivalence [126].

Currently available oral iron agents have variable effectiveness in increasing Hb, ferritin, and TSAT, as well as in reducing the use of ESAs or blood transfusions [127]. Compared with iv iron, oral iron is less effective in correcting iron deficiency and reducing ESA needs [128]. Given that gastrointestinal side effects are frequent with oral iron administration, many oral iron preparations are poorly tolerated. Additional concerns include poor absorption and altering colonic microflora. Considering that oral iron formulations are noninvasive, avoid injection site complications, and consume venous capital for future access, creation can be a suitable method for ND-CKD patients. Furthermore, it should be underlined that most of the data were derived from comparing older iron preparations. In addition to traditional iron agents, novel oral iron preparations have been developed to improve the treatment efficacy. One of these agents, ferric citrate, has been shown to improve iron parameters and has been proven to be an effective treatment for anemia in ND-CKD patients [129,130]. Furthermore, ferric citrate has been proven effective in reducing iv iron and ESA needs, with a good tolerability, in patients undergoing HD [131]. The liposomal iron represents another example of a new generation of oral iron preparations, which shows high gastrointestinal absorption and high bioavailability [132]. Compared with other traditional oral iron agents, liposomal iron avoids the direct contact of iron with the intestinal mucosa and bypasses the intestinal hepcidin–ferroportin block via a different uptake mechanism. In a small trial by Pisani et al., liposomal iron was proven to increase Hb in ND-CKD patients [133]. Ferric pyrophosphate citrate (FPC) is a water-soluble iron salt that can be administered via dialysate or iv [130]. Compared with iv iron agents, FPC via dialysate presents the advantage of supplying the iron directly to transferrin. FPC has been proven effective in Hb maintaining and decreasing ESA needs [134]. Iv iron agents have comparable efficacy in improving Hb, ferritin, and TSAT and reducing the use of ESAs or blood transfusions [135]. However, some data show that iron sucrose similars have decreased efficacy and safety compared with parent iron sucrose [135]. Kalra et al. [136] studied 351 iron-deficient ND-CKD patients and randomized them 2:1 to either IV iron isomaltoside 1000 or iron sulphate (100 mg of elemental oral iron twice daily for 8 weeks). Isomaltoside 1000 was superior to oral iron sulphate in increasing Hb levels and was well tolerated. Results from the PIVOTAL trial [20,137,138] are reassuring, regarding the iv iron administration in patients with short dialysis vintage, no or minimal inflammation, and up to ferritin of 700 ng/mL. However, the question arises, whether this regimen is safe and efficacious in patients with comorbidities, inflamed, and dialyzed for a long-time. In the modern world, this is a prevalent population in HD units. In ND-CKD patients, FIND-CKD study ferritin levels of 800 ng/mL or above did not result in an increase in serious adverse events after administration of ferric carboxymaltose [122]. In addition, the grey area of knowledge is the potential mechanisms by which a high-dose iron regimen (iron sucrose) was associated with improved outcomes in the PIVOTAL study [20]. Macdougall et al. also showed a randomized, controlled trial, that ferumoxytol and iron sucrose showed comparable efficacy and adverse events rates [139]. In addition, recently, Macdougall et al. [140] reported that long-term administration of ferumoxytol has noninferior efficacy and a similar safety profile to iron sucrose when used to treat IDA in patients with CKD undergoing hemodialysis. Whether newer iron preparations such as ferric carboxymaltose or iron isomaltose yield the same positive results remains to be studied. Hypophosphataemia is an increasingly recognized side effect of ferric car-boxymaltose (FCM) and possibly iron isomaltoside/ferric derisomaltose (IIM), which are used to treat iron deficiency. Schaefer et al. [141] included 42 clinical trials in the meta-analysis and found that FCM induced a significantly higher incidence of hypophosphataemia than IIM (47%, 95% CI 36–58% versus 4%, 95% CI 2–5%) and significantly greater mean decreases in serum phosphate (0.40 versus 0.06 mmol/L). More severe iron deficiency and normal kidney function are risk factors for hypophosphataemia. However, this side effect seems less important in CKD patients who have often high basal phosphate levels. Future trials focusing on long-term effects and optimal dosing strategies of novel oral iron preparations should be conducted.

5. Other New Therapeutic Strategies

As previously discussed, iron metabolism is dysregulated in patients with CKD, contributing to the development and progression of CKD-related anemia. Given that hepcidin is a key regulator of iron balance, the strategy of decreasing hepcidin was recently proposed as a promising therapeutic option. These findings lead to the exploration of therapeutic approaches of targeting iron metabolism, including inhibitors of hepcidin, IL-6 antibodies, and other anti-inflammatory biologicals (inhibition of the BMP6, SMAD, HJV, and IL-6/STAT cascades) [142]. Hepcidin antibodies have been shown to bind human (and monkey) hepcidin, inhibit its action on ferroportin, enhance the dietary iron absorption, and promote the mobilization of its stores [142]. The ferroportin stabilizers tend to reduce hepcidin expression, inhibit its action, and prevent ferroportin degradation [142]. Antiferroportin monoclonal antibody (LY 2928057) blocks hepcidin interaction with its receptor, thereby reducing ferroportin internalization and allowing more iron flux [138]. In CKD patients, the administration of LY2928057 resulted in an increase in Hb and a reduction in serum ferritin levels [53]. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a major inducer of hepcidin production. A small study demonstrated that inhibitors of the IL-6 pathway decreased hepcidin levels and ameliorated anemia in Castleman’s disease. Likewise, blocking antibodies to the IL-6 ligand has been proven effective in lowering hepcidin [142]. Siltuximab, the anti-IL-6 chimeric monoclonal antibody, increased Hb levels by 2.1 g/dL; however, it has been associated with a greater risk of infections [143]. Lipocalins are low-molecular-weight proteins that naturally bind, store, and transport a wide spectrum of molecules, e.g., hormones [144]. Anticalins are proteins with engineered ligand-binding properties derived from the human’s lipocalin. PRS-080, an anticalin against hepcidin, efficiently and specifically sequester hepcidin [144,145]. A study in DD-CKD patients demonstrated neutralization of hepcidin by PRS-080 and a subsequent increase in serum iron and TSAT following PRS-080 administration [144,145].

6. Conclusions

CKD is one of the main causes of death internationally and requires the better prevention and treatment. For years, ESAs have remained a cornerstone of therapy for anemia in CKD together with iron supplementation. Novel therapeutic strategies are imperative for improving anemia in patients with CKD. HIF-PHIs, unlike conventional ESAs, stimulate the transcription of the EPO gene in the kidneys and liver, leading to increased levels of endogenous erythropoietin. HIF-PHIs have been reported to be at least as efficacious as ESAs in the correction of anemia in CKD, without increasing the incidence of adverse events in the short term. Furthermore, HIF-PHIs seem to offer unique pharmacological effects such as improving iron utilization and pleiotropic effects. On the other hand, classic ESAs have a comprehensive safety profile, which should be the future comparison standard for the new class of drugs.

7. Summary

For almost 40 years, we have expanded our understanding of ESAs and iron (for iron even more) as major antianemic drugs. As the first of innovative ESAs started to come off patent, biosimilar biologic agents have been introduced as alternatives for the treatment of anemia in many countries [146,147]. In addition, follow-up versions of iron sucrose have emerged to treat iron-deficiency anemia, including renal anemia, in a number of countries worldwide. The assumption was that iron sucrose similar agents could be considered therapeutically equivalent to the originator iron sucrose. Many promising novel agents appeared in recent years; however, some of them such as peginesatide turned out to be a falling star. In the 21st century, anemia still remains a widespread complication of CKD that contributes to worse outcomes and lowers the quality of life. Taking into consideration the fact that blood products are not only a scarce resource but they are often in a short supply, we should also be concerned about the low but still real possibility of viral transmission and the increased risk of HLA sensitization, which may be responsible for longer time on the waiting list for transplantation, increased graft rejection, and poorer graft survival [148]. In addition, the usage of iv iron agents and multiple blood transfusions that inevitably result in cumulative iron overload represented another clinical problem with unknown long-term clinical relevance [149]. These trends highlight the need for new research to find agents effective in these new settings with no safety concerns.

Data from observational, randomized controlled trials and case reports lead to the exploration of therapeutic approaches for treating the anemia of CKD. Inhibitors of the hepcidin–ferroportin axis are in development at preclinical and clinical stages. Several HIF stabilizers are studied in phase 2 and 3 trials with promising results. HIF stabilizers have been shown to be at least as efficacious as classic ESA in the short term. The ultimate goal of renal anemia treatment is to affect iron together or without “good, old” strategies such as ESAs therapy or “novel and hopefully better” such as HIF stabilizers (Figure 2). HIF-PHIs could hold the potential to change the scene of renal anemia treatment in the near future, if they demonstrate a noninferior safety profile compared to classic ESAs. Renal anemia treatment with a particular focus on iron was the matter of “Optimal Anemia Management: Conclusions from KDIGO Conference in December 2019” in the recent publication in 2021 [150]. We did explore new and ongoing controversies, together with possible implications for changes of the current KDIGO anemia guideline, and proposals of research agenda. The second controversy conference is planned for the end of 2021 with a particular focus on issues more specifically related to HIF inhibitors.

Figure 2.

Pathophysiology of renal anemia and treatment options.

Author Contributions

B.B. and J.M. contributed to the conception and study design, data acquisition, analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript drafting. J.S.M. and M.K. were involved in data analysis/interpretation. J.M. and J.S.M. contributed to drafting the manuscript and revising its final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Foreman, K.J.; Marquez, N.; Dolgert, A.; Fukutaki, K.; Fullman, N.; McGaughey, M.; Pletcher, M.A.; Smith, A.E.; Tang, K.; Yuan, C.W.; et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: Reference and alternative scenarios for 2016–40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet 2018, 392, 2052–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenga, M.F.; Nolte, I.M.; van der Meer, P.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Gaillard, C.A.J.M. Association of different iron deficiency cutoffs with adverse outcomes in chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2018, 19, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, M.E.; Fan, T. Prevalence of anemia in chronic kidney disease in the United States. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, R.M.; Streja, E.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Burden of Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease: Beyond Erythropoietin. Adv Ther. 2021, 38, 52–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Yin, Q.; Han, Y.C.; Wu, M.; Li, Z.L.; Tu, Y.; Zhou, L.T.; Wei, Q.; Liu, H.; Tang, R.N.; et al. Effect of hypoxia-inducible factor-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors on anemia in patients with CKD: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials including 2804 patients. Ren. Fail. 2020, 42, 912–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, D.; Goldsmith, D.; Teitsson, S.; Jackson, J.; van Nooten, F. Cross-sectional survey in CKD patients across Europe describing the association between quality of life and anaemia. BMC Nephrol. 2016, 17, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaker, A.M.; Mohamed, O.M.; Mohamed, M.F.; El-Khashaba, S.O. Impact of correction of anemia in end-stage renal disease patients on cerebral circulation and cognitive functions. Saudi J. Kidney Dis. Transplant. 2018, 29, 1333–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majernikova, M.; Rosenberger, J.; Prihodova, L.; Jarcuskova, M.; Roland, R.; Groothoff, J.W.; van Dijk, J.P. Posttransplant anemia as a prognostic factor of mortality in kidney-transplant recipients. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 6987240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenga, M.F.; Minović, I.; Berger, S.P.; Kootstra-Ros, J.E.; van den Berg, E.; Riphagen, I.J.; Navis, G.; van der Meer, P.; Bakker, S.J.; Gaillard, C.A. Iron deficiency, anemia, and mortality in renal transplant recipients. Transpl Int. 2016, 29, 1176–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besarab, A.; Ross, R.P.; Nasca, T.J. The use of recombinant human erythropoietin in predialysis patients. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 1995, 4, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babitt, J.L.; Lin, H.Y. Mechanisms of anemia in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 23, 1631–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, K.U.; Agarwal, R.; Farag, Y.M.; Jardine, A.G.; Khawaja, Z.; Koury, M.J.; Luo, W.; Matsushita, K.; McCullough, P.A.; Parfrey, P.; et al. Global Phase 3 programme of vadadustat for treatment of anaemia of chronic kidney disease: Rationale, study design and baseline characteristics of dialysis-dependent patients in the INNO2VATE trials. Nephrol. Dial Transplant. 2020, gfaa204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kular, D.; Macdougall, I.C. HIF stabilizers in the management of renal anemia: From bench to bedside to pediatrics. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2019, 34, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, T.; Matsubara, T.; Akashi, Y.; Kondo, M.; Yanagita, M. Annual iron loss associated with hemodialysis. Am. J. Nephrol. 2016, 43, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafter-Gvili, A.; Schechter, A.; Rozen-Zvi, B. Iron deficiency anemia in chronic kidney disease. Acta Haematol. 2019, 142, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erslev, A. Humoral regulation of red cell production. Blood 1953, 8, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, L.O.; Goldwasser, E.; Fried, W.; Plzak, L.F. Studies on erythropoiesis. VII. The role of the kidney in the production of erythropoietin. Trans. Assoc. Am. Physicians 1957, 70, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miyake, T.; Kung, C.K.; Goldwasser, E. Purification of human erythropoietin. J. Biol. Chem. 1977, 252, 5558–5564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.K.; Suggs, S.; Lin, C.H.; Browne, J.K.; Smalling, R.; Egrie, J.C.; Chen, K.K.; Fox, G.M.; Martin, F.; Stabinsky, Z. Cloning and expression of the human erythropoietin gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1985, 82, 7580–7584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Liu, X.; Henry, L.; Harman, J.; Ross, E.A. Trends in anemia care in non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients in the United States (2006–2015). BMC Nephrol. 2018, 19, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covic, A.; Nistor, I.; Donciu, M.D.; Dumea, R.; Bolignano, D.; Goldsmith, D. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA) for preventing the progression of chronic kidney disease: A meta-analysis of 19 studies. Am. J. Nephrol. 2014, 40, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, F.; Del Vecchio, L. New Strategies for Anaemia Management in Chronic Kidney Disease. Contrib. Nephrol. 2017, 189, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, Y.; Hamano, T.; Wada, A.; Masakane, I. Types of erythropoietin-stimulating agents and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 30, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoppa, G.; D’Amore, C.; Conforti, A.; Traversa, G.; Venegoni, M.; Taglialatela, M.; Leone, R.; ESAVIEW Study Group. Comparative safety of originator and biosimilar epoetin alfa drugs: An observational prospective multicenter study. BioDrugs 2018, 32, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belleudi, V.; Trotta, F.; Addis, A.; Ingrasciotta, Y.; Ientile, V.; Tari, M.; Gini, R.; Pastorello, M.; Scondotto, S.; Cananzi, P.; et al. Effectiveness and safety of switching originator and biosimilar epoetins in patients with chronic kidney disease in a large-scale Italian cohort study. Drug Saf. 2019, 42, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczech, L.A.; Barnhart, H.X.; Inrig, J.K.; Reddan, D.N.; Sapp, S.; Califf, R.M.; Patel, U.D.; Singh, A.K. Secondary analysis of the CHOIR trial epoetin-alpha dose and achieved hemoglobin outcomes. Kidney Int. 2008, 74, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, K.U.; Scherhag, A.; Macdougall, I.C.; Tsakiris, D.; Clyne, N.; Locatelli, F.; Zaug, M.F.; Burger, H.U.; Drueke, T.B. Left ventricular geometry predicts cardiovascular outcomes associated with anemia correction in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 2651–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besarab, A.; Bolton, W.K.; Browne, J.K.; Egrie, J.C.; Nissenson, A.R.; Okamoto, D.M.; Schwab, S.J.; Goodkin, D.A. The effects of normal as compared with low hematocrit values in patients with cardiac disease who are receiving hemodialysis and epoetin. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeffer, M.A.; Burdmann, E.A.; Chen, C.Y.; Cooper, M.E.; de Zeeuw, D.; Eckardt, K.U.; Feyzi, J.M.; Ivanovich, P.; Kewalramani, R.; Levey, A.S.; et al. A trial of darbepoetin alfa in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 2019–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Anemia Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for anemia in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2012, 2, 279–335. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, A.J.; Foley, R.N.; Gilbertson, D.T.; Chen, S.C. United States Renal Data System public health surveillance of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2015, 5, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, D.S.; Bieber, B.A.; Pisoni, R.L.; Li, Y.; Morgenstern, H.; Akizawa, T.; Jacobson, S.H.; Locatelli, F.; Port, F.K.; Robinson, B.M. International comparisons to assess effects of payment and regulatory changes in the United States on anemia practice in patients on hemodialysis: The dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 2205–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, D.S.; Zepel, L.; Bieber, B.A.; Robinson, B.M.; Pisoni, R.L. Hemodialysis facility variation in hospitalization and transfusions using medicare claims: The DOPPS Practice Monitor for US dialysis care. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 67, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mimura, I.; Tanaka, T.; Nangaku, M. How the target hemoglobin of renal anemia should be? Nephron 2015, 131, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koulouridis, I.; Alfayez, M.; Trikalinos, T.A.; Balk, E.M.; Jaber, B.L. Dose of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and adverse outcomes in CKD: A metaregression analysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2013, 61, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.G.; Wright, E.C.; Narva, A.S.; Noguchi, C.T.; Eggers, P.W. Association of erythropoietin dose and route of administration with clinical outcomes for patients on hemodialysis in the United States. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 10, 1822–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, R. Hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors in patients with renal anemia: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Nephron 2020, 144, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, L.; Addis, A.; Saulle, R.; Trotta, F.; Mitrova, Z.; Davoli, M. Comparative efficacy and safety in ESA biosimilars vs. originators in adults with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nephrol. 2018, 31, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camaschella, C.; Nai, A.; Silvestri, L. Iron metabolism and iron disorders revisited in the hepcidin era. Hematologica 2020, 105, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theurl, I.; Aigner, E.; Theurl, M.; Nairz, M.; Seifert, M.; Schroll, A.; Sonnweber, T.; Eberwein, L.; Witcher, D.R.; Murphy, A.T.; et al. Regulation of iron homeostasis in anemia of chronic disease and iron deficiency anemia: Diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Blood 2009, 113, 5277–5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffel, N.U.; Lazrak, M.; Bellitir, S.; Mir, N.E.; Hamdouchi, A.E.; Barkat, A.; Zeder, C.; Moretti, D.; Aguenaou, H.; Zimmermann, M.B. The opposing effects of acute inflammation and iron deficiency anemia on serum hepcidin and iron absorption in young women. Haematologica 2019, 104, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangkhae, V.; Nemeth, E. To induce or not to induce: The fight over hepcidin regulation. Haematologica 2019, 104, 1093–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Szczech, L.; Tang, K.L.; Barnhart, H.; Sapp, S.; Wolfson, M.; Reddan, D.; CHOIR Investigators. Correction of anemia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidney disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 2085–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, N.A.; Lewis, E.F.; Desai, A.S.; Anand, I.S.; Krum, H.; McMurray, J.J.; Olson, K.; Solomon, S.D.; Swedberg, K.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; et al. Increased risk of stroke with darbepoetin alfa in anaemic heart failure patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 1201–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfrey, P.S.; Foley, R.N.; Wittreich, B.H.; Sullivan, D.J.; Zagari, M.J.; Frei, D. Double-blind comparison of full and partial anemia correction in incident hemodialysis patients without symptomatic heart disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005, 16, 2180–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akizawa, T.; Nangaku, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Arai, M.; Koretomo, R.; Matsui, A.; Hirakata, H. A placebo-controlled, randomized trial of enarodustat in patients with chronic kidney disease followed by long-term trial. Am. J. Nephrol. 2019, 49, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choukroun, G.; Kamar, N.; Dussol, B.; Etienne, I.; Cassuto-Viguier, E.; Toupance, O.; Glowacki, F.; Moulin, B.; Lebranchu, Y.; Touchard, G.; et al. Correction of postkidney transplant anemia reduces progression of allograft nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 23, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Vecchio, L.; Locatelli, F. An overview on safety issues related to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for the treatment of anaemia in patients with chronic kidney disease. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2016, 15, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatelli, F.; Del Vecchio, L.; De Nicola, L.; Minutolo, R. Are all erythropoiesis-stimulating agents created equal? Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drüeke, T.B.; Locatelli, F.; Clyne, N.; Eckardt, K.U.; Macdougall, I.C.; Tsakiris, D.; Burger, H.U.; Scherhag, A.; CREATE Investigators. Normalization of hemoglobin level in patients with chronic kidney disease and anemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 2071–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.W.; Pollock, C.A.; Macdougall, I.C. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agent hyporesponsiveness. Nephrology 2007, 12, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, P.A.; Barnhart, H.X.; Inrig, J.K.; Reddan, D.; Sapp, S.; Patel, U.D.; Singh, A.K.; Szczech, L.A.; Califf, R.M. Cardiovascular toxicity of epoetin-alfa in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Nephrol. 2013, 37, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutov, E.; Sułowicz, W.; Esposito, C.; Tataradze, A.; Andric, B.; Reusch, M.; Valluri, U.; Dimkovic, N. Roxadustat for the treatment of anemia in chronic kidney disease patients not on dialysis: A phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (ALPS). Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 1629–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, J.M.; Sharma, N.; Dikdan, S. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor and Its Role in the Management of Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akizawa, T.; Macdougall, I.C.; Berns, J.S.; Yamamoto, H.; Taguchi, M.; Iekushi, K.; Bernhardt, T. Iron regulation by molidustat, a daily oral hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor, in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephron 2019, 143, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, C.; Tsuchiya, K.; Tomosugi, N.; Maeda, K. A Hypoxia-inducible factor stabilizer improves hematopoiesis and iron metabolism early after administration to treat anemia in hemodialysis patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.K.; Blackorby, A.; Cizman, B.; Carroll, K.; Cobitz, A.R.; Davies, R.; Jha, V.; Johansen, K.L.; Lopes, R.D.; Kler, L.; et al. Study design and baseline characteristics of patients on dialysis in the ASCEND-D trial. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, gfab065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdougall, I.C.; Akizawa, T.; Berns, J.S.; Bernhardt, T.; Krueger, T. Effects of Molidustat in the treatment of anemia in CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 17, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, K.U.; Agarwal, R.; Aswad, A.; Awad, A.; Block, G.A.; Bacci, M.R.; Farag, Y.M.K.; Fishbane, S.; Hubert, H.; Jardine, A.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Vadadustat for Anemia in Patients Undergoing Dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1601–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wish, J.B.; Eckardt, K.U.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Fishbane, S.; Spinowitz, B.S.; Berns, J.S. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Stabilization as an Emerging Therapy for CKD-Related Anemia: Report from a Scientific Workshop Sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besarab, A.; Provenzano, R.; Hertel, J.; Zabaneh, R.; Klaus, S.J.; Lee, T.; Leong, R.; Hemmerich, S.; Yu, K.H.; Neff, T.B. Randomized placebo-controlled dose-ranging and pharmacodynamics study of roxadustat (FG-4592) to treat anemia in nondialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease (NDD-CKD) patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2015, 30, 1665–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzano, R.; Besarab, A.; Sun, C.H.; Diamond, S.A.; Durham, J.H.; Cangiano, J.L.; Aiello, J.R.; Novak, J.E.; Lee, T.; Leong, R.; et al. Oral hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor roxadustat (FG-4592) for the treatment of anemia in patients with CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 11, 982–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Qian, J.; Chen, J.; Yu, X.; Mei, C.; Hao, C.; Jiang, G.; Lin, H.; Zhang, X.; Zuo, L.; et al. Phase 2 studies of oral hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor FG-4592 for treatment of anemia in China. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2017, 32, 1373–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provenzano, R.; Besarab, A.; Wright, S.; Dua, S.; Zeig, S.; Nguyen, P.; Poole, L.; Saikali, K.G.; Saha, G.; Hemmerich, S.; et al. Roxadustat (FG-4592) versus epoetin alfa for anemia in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis: A Phase 2, randomized, 6- to 19-week, open-label, active-comparator, dose-ranging, safety and exploratory efficacy study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 67, 912–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besarab, A.; Chernyavskaya, E.; Motylev, I.; Shutov, E.; Kumbar, L.M.; Gurevich, K.; Chan, D.T.; Leong, R.; Poole, L.; Zhong, M.; et al. Roxadustat (FG-4592): Correction of anemia in incident dialysis patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergola, P.E.; Spinowitz, B.S.; Hartman, C.S.; Maroni, B.J.; Haase, V.H. Vadadustat, a novel oral HIF stabilizer, provides effective anemia treatment in nondialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2016, 90, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, E.R.; Smith, M.T.; Maroni, B.J.; Zuraw, Q.C.; deGoma, E.M. Clinical trial of vadadustat in patients with anemia secondary to Stage 3 or 4 chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Nephrol. 2017, 45, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haase, V.H.; Chertow, G.M.; Block, G.A.; Pergola, P.E.; deGoma, E.M.; Khawaja, Z.; Sharma, A.; Maroni, B.J.; McCullough, P. Effects of vadadustat on hemoglobin concentrations in patients receiving hemodialysis previously treated with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2019, 34, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdstock, L.; Meadowcroft, A.M.; Maier, R.; Johnson, B.M.; Jones, D.; Rastogi, A.; Zeig, S.; Lepore, J.J.; Cobitz, A.R. Four-week studies of oral hypoxia-inducible factor-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor GSK1278863 for treatment of anemia. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 1234–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigandi, R.A.; Johnson, B.; Oei, C.; Westerman, M.; Olbina, G.; de Zoysa, J.; Roger, S.D.; Sahay, M.; Cross, N.; McMahon, L.; et al. A novel hypoxia-inducible factor-prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor (GSK1278863) for anemia in CKD: A 28-day, phase 2A randomized trial. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 67, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akizawa, T.; Tsubakihara, Y.; Nangaku, M.; Endo, Y.; Nakajima, H.; Kohno, T.; Imai, Y.; Kawase, N.; Hara, K.; Lepore, J.; et al. Effects of daprodustat, a novel hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor on anemia management in Japanese hemodialysis subjects. Am. J. Nephrol. 2017, 45, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, A.M.; Cizman, B.; Holdstock, L.; Biswas, N.; Johnson, B.M.; Jones, D.; Nossuli, A.K.; Lepore, J.J.; Aarup, M.; Cobitz, A.R. Daprodustat for anemia: A 24-week, open-label, randomized controlled trial in participants on hemodialysis. Clin. Kidney J. 2019, 12, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, D.V.; Kansagra, K.A.; Patel, J.C.; Joshi, S.N.; Sharma, N.S.; Shelat, A.D.; Patel, N.B.; Nakrani, V.B.; Shaikh, F.A.; Patel, H.V.; et al. Outcomes of desidustat treatment in people with anemia and chronic kidney disease: A Phase 2 Study. Am. J. Nephrol. 2019, 49, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Hao, C.; Peng, X.; Lin, H.; Yin, A.; Hao, L.; Tao, Y.; Liang, X.; Liu, Z.; Xing, C.; et al. Roxadustat for anemia in patients with kidney disease not receiving dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Hao, C.; Liu, B.C.; Lin, H.; Wang, C.; Xing, C.; Liang, X.; Jiang, G.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; et al. Roxadustat treatment for anemia in patients undergoing long-term dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akizawa, T.; Otsuka, T.; Reusch, M.; Ueno, M. Intermittent oral dosing of roxadustat in peritoneal dialysis chronic kidney disease patients with anemia: A Randomized, Phase 3, multicenter, open-label study. Ther. Apher. Dial. 2020, 24, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbane, S.; El-Shahawy, M.A.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Van, B.P.; Houser, M.T.; Frison, L.; Little, D.J.; Guzman, N.J.; Pergola, P.E. Roxadustat for treating anemia in patients with CKD not on dialysis: Results from a randomized phase 3 study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 32, 737–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzano, R.; Shutov, E.; Eremeeva, L.; Korneyeva, S.; Poole, L.; Saha, G.; Bradley, C.; Eyassu, M.; Besarab, A.; Leong, R.; et al. Roxadustat for anemia in patients with end-stage renal disease incident to dialysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 1717–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akizawa, T.; Iwasaki, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Majikawa, Y.; Reusch, M. Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, active-comparator (darbepoetin alfa) study of oral Roxadustat in CKD patients with anemia on hemodialysis in Japan. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 31, 1628–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akizawa, T.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Otsuka, T.; Reusch, M. A Phase 3, Multicenter, randomized, two-arm, open-label study of intermittent oral dosing of Roxadustat for the treatment of anemia in japanese erythropoiesis-stimulating agent-naïve chronic kidney disease patients not on dialysis. Nephron 2020, 144, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, D.W.; Roger, S.D.; Shin, S.K.; Kim, S.G.; Cadena, A.A.; Moustafa, M.A.; Chan, T.M.; Besarab, A.; Chou, W.; Bradley, C.; et al. Roxadustat for CKD-related anemia in non-dialysis patients. Kidney Int. Rep. 2020, 6, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nangaku, M.; Kondo, K.; Ueta, K.; Kokado, Y.; Kaneko, G.; Matsuda, H.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Komatsu, Y. Efficacy and safety of vadadustat compared with darbepoetin alfa in japanese anemic patients on hemodialysis: A phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 1731–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akizawa, T.; Nangaku, M.; Yonekawa, T.; Okuda, N.; Kawamatsu, S.; Onoue, T.; Endo, Y.; Hara, K.; Cobitz, A.R. Efficacy and safety of daprodustat compared with darbepoetin alfa in Japanese hemodialysis patients with anemia: A randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 15, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubakihara, Y.; Akizawa, T.; Nangaku, M.; Onoue, T.; Yonekawa, T.; Matsushita, H.; Endo, Y.; Cobitz, A. A 24-week anemia correction study of daprodustat in Japanese dialysis patients. Ther. Apher. Dial. 2020, 24, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomini, M.; Del Vecchio, L.; Sirolli, V.; Locatelli, F. New Treatment Approaches for the Anemia of CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 67, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenza, G.L. Oxygen sensing, homeostasis, and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanghani, N.S.; Haase, V.H. Hypoxia-inducible factor activators in renal anemia: Current clinical experience. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019, 26, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrogiannaki, M.; Matak, P.; Mathieu, J.R.; Delga, S.; Mayeux, P.; Vaulont, S.; Peyssonnaux, C. Hepatic hypoxia-inducible factor-2 down-regulates hepcidin expression in mice through an erythropoietin-mediated increase in erythropoiesis. Haematologica 2012, 97, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.L.; Leissing, T.M.; Abboud, M.I.; Thinnes, C.C.; Atasoylu, O.; Holt-Martyn, J.P.; Zhang, D.; Tumber, A.; Lippl, K.; Lohans, C.T.; et al. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors in clinical trials. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 7651–7668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Davidoff, O.; Niss, K.; Haase, V.H. Hypoxia-inducible factor regulates hepcidin via erythropoietin-induced erythropoiesis. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 4635–4644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qie, S.; Jiao, N.; Duan, K.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, G. The efficacy and safety of roxadustat treatment for anemia in patients with kidney disease: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2021, 53, 985–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akizawa, T.; Iwasaki, M.; Otsuka, T.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Reusch, M. Phase 3 study of roxadustat to treat anemia in non-dialysis-dependant CKD. Kidney Int. Rep. 2021, 6, 1810–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, Y.; Xie, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, R.; Yan, X. Roxadustat Does Not Affect Platelet Production, Activation, and Thrombosis Formation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, J.; Andric, B.; Tataradze, A.; Schömig, M.; Reusch, M.; Valluri, U.; Mariat, C. Roxadustat for the treatment of anaemia in chronic kidney disease patients not on dialysis: A phase 3, randomised, open-label, active-controlled study (DOLOMITES). Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 1616–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charytan, C.; Manllo-Karim, R.; Martin, E.R.; Steer, D.; Bernardo, M.; Dua, S.L.; Moustafa, M.A.; Saha, G.; Bradley, C.; Eyassu, M.; et al. A randomized trial of Roxadustat in anemia of kidney failure: SIERRAS Study. Kidney Int. Rep. 2021, 6, 1829–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertow, G.M.; Pergola, P.E.; Farag, Y.M.K.; Agarwal, R.; Arnold, S.; Bako, G.; Block, G.A.; Burke, S.; Castillo, F.P.; Jardine, A.G.; et al. Vadadustat in patients with anemia and non-dialysis-dependent CKD. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1589–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akizawa, T.; Nangaku, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Koretomo, R.; Maeda, K.; Miyazawa, Y.; Hirakata, H. A Phase 3 Study of Enarodustat in anemic patients with CKD not requiring dialysis: The SYMPHONY ND Study. Kidney Int. Rep. 2021, 6, 1840–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akizawa, T.; Nobori, K.; Matsuda, Y.; Taki, K.; Hayashi, Y.; Hayasaki, T.; Yamamoto, H. Molidustat for the treatment of anemia in Japanese patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis: A single-arm, open-label, phase 3 study. Ther. Apher. Dial. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzano, R.; Szczech, L.; Leong, R.; Saikali, K.G.; Zhong, M.; Lee, T.T.; Little, D.J.; Houser, M.T.; Frison, L.; Houghton, J.; et al. Efficacy and cardiovascular safety of Roxadustat for treatment of anemia in patients with non-dialysis-dependent CKD: Pooled results of three randomized clinical trials. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 16, 1190–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/summaries-opinion/evrenzo (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Available online: https://fibrogen.gcs-web.com/news-releases/news-release-details/fibrogen-provides-additional-information-roxadustat (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Available online: https://icer.org/assessment/anemia-in-chronic-kidney-disease-2021/ (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Available online: https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar/updated-time-information-july-15-2021-meeting-cardiovascular-and-renal-drugs-advisory-committee#event-materials (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Shen, G.M.; Zhao, Y.Z.; Chen, M.T.; Zhang, F.L.; Liu, X.L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.Z.; Yu, J.; Zhang, J.W. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) promotes LDL and VLDL uptake through inducing VLDLR under hypoxia. Biochem. J. 2012, 441, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamme, I.; Oehme, F.; Ellinghaus, P.; Jeske, M.; Keldenich, J.; Thuss, U. Mimicking hypoxia to treat anemia: HIF-stabilizer BAY 85–3934 (Molidustat) stimulates erythropoietin production without hypertensive effects. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltzschig, H.K.; Bratton, D.L.; Colgan, S.P. Targeting hypoxia signalling for the treatment of ischaemic and inflammatory diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 852–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggar, P.; Kim, G.H. Treatment of renal anemia: Erythropoiesis stimulating agents and beyond. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 36, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowburn, A.S.; Crosby, A.; Macias, D.; Branco, C.; Colaço, R.D.; Southwood, M.; Toshner, M.; Crotty Alexander, L.E.; Morrell, N.W.; Chilvers, E.R.; et al. HIF2α-arginase axis is essential for the development of pulmonary hypertension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 8801–8806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, A.; Peters, D.J.M.; Klanke, B.; Weidemann, A.; Willam, C.; Schley, G.; Kunzelmann, K.; Eckardt, K.U.; Buchholz, B. HIF-1α promotes cyst progression in a mouse model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2018, 94, 887–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Lv, F.L.; Wang, G.H. Effects of HIF-1α on diabetic retinopathy angiogenesis and VEGF expression. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 5071–5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokas, S.; Larivière, R.; Lamalice, L.; Gobeil, S.; Cornfield, D.N.; Agharazii, M.; Richard, D.E. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 plays a role in phosphate-induced vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. Kidney Int. 2016, 90, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akizawa, T.; Iekushi, K.; Matsuda, Y. P1866 to investigate the efficacy and safety of molidustat in non-dialysis patients with renal anemia who are not treated with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents: Miyabi Nd-C. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2020, 35, iii2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akizawa, T.; Iekushi, K.; Matsuda, Y. P1868 to investigate the efficacy and safety of molidustat in non-dialysis patients with renal anemia who are treated with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents: Miyabi Nd-M. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2020, 35, iii2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akizawa, T.; Nobori, K.; Matsuda, Y.; Hayashi, Y.; Hayasaki, T.; Yamamoto, H. Molidustat for anemia correction in Japanese patients undergoing hemodialysis: A single-arm, phase 3 study. Ther. Apher. Dial. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akizawa, T.; Nangaku, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Koretomo, R.; Maeda, K.; Yamada, O.; Hirakata, H. Two long-term phase 3 studies of enarodustat (JTZ-951) in Japanese anemic patients with chronic kidney disease not on dialysis or on maintenance hemodialysis: SYMPHONY ND-Long and HD-Long Studies. Ther. Apher. Dial. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapter 2: Use of iron to treat anemia in CKD. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2012, 2, 292–298. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardiner, R.; Roshan, D.; Brennan, A.; Connolly, D.; Murray, S.; Reddan, D. Trends in the treatment of chronic kidney disease-associated anaemia in a cohort of haemodialysis patients: The Irish experience. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 188, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, M.; Suttorp, M.M.; Bellocco, R.; Hoekstra, T.; Qureshi, A.R.; Dekker, F.W.; Carrero, J.J. Trends in haemoglobin, erythropoietin-stimulating agents and iron use in Swedish chronic kidney disease patients between 2008 and 2013. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2016, 31, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, F.; Bárány, P.; Covic, A.; De Francisco, A.; Del Vecchio, L.; Goldsmith, D.; Hörl, W.; London, G.; Vanholder, R.; Van Biesen, W.; et al. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines on anaemia management in chronic kidney disease: A European Renal Best Practice position statement. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 28, 1346–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellini, M.D.; Comin-Colet, J.; de Francisco, A.; Dignass, A.; Doehner, W.; Lam, C.S.; Macdougall, I.C.; Rogler, G.; Camaschella, C.; Kadir, R.; et al. Iron deficiency across chronic inflammatory conditions: International expert opinion on definition, diagnosis, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2017, 92, 1068–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Vecchio, L.; Ekart, R.; Ferro, C.J.; Malyszko, J.; Mark, P.B.; Ortiz, A.; Sarafidis, P.; Valdivielso, J.M.; Mallamaci, F.; ERA-EDTA European Renal and Cardiovascular Medicine Working (EURECA-m) Group. Intravenous iron therapy and the cardiovascular system: Risks and benefits. Clin. Kidney J. 2020, 14, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdougall, I.C.; Bock, A.H.; Carrera, F.; Eckardt, K.U.; Gaillard, C.; Van Wyck, D.; Roubert, B.; Nolen, J.G.; Roger, S.D.; FIND-CKD Study Investigators. FIND-CKD: A randomized trial of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose versus oral iron in patients with chronic kidney disease and iron deficiency anaemia. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2014, 29, 2075–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hougen, I.; Collister, D.; Bourrier, M.; Ferguson, T.; Hochheim, L.; Komenda, P.; Rigatto, C.; Tangri, N. Safety of Intravenous Iron in Dialysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 13, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdougall, I.C.; Bhandari, S.; White, C.; Anker, S.D.; Farrington, K.; Kalra, P.A.; Mark, P.B.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Reid, C.; Robertson, M.; et al. intravenous iron dosing and infection risk in patients on hemodialysis: A prespecified secondary analysis of the PIVOTAL trial. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 31, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cole, S.R.; Kshirsagar, A.V.; Fine, J.P.; Sturmer, T.; Brookhart, M.A. Safety of dynamic intravenous iron administration strategies in hemodialysis patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 14, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rottembourg, J.; Kadri, A.; Leonard, E.; Dansaert, A.; Lafuma, A. Do two intravenous iron sucrose preparations have the same efficacy? Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011, 26, 3262–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pergola, P.E.; Fishbane, S.; Ganz, T. Novel oral iron therapies for iron deficiency anemia in chronic kidney disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019, 26, 272–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepshelovich, D.; Rozen-Zvi, B.; Avni, T.; Gafter, U.; Gafter-Gvili, A. Intravenous versus oral iron supplementation for the treatment of anemia in CKD: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 68, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, G.A.; Block, M.S.; Smits, G.; Mehta, R.; Isakova, T.; Wolf, M.; Chertow, G.M. A Pilot Randomized Trial of Ferric Citrate Coordination Complex for the Treatment of Advanced CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 30, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbane, S.; Block, G.A.; Loram, L.; Neylan, J.; Pergola, P.E.; Uhlig, K. Effects of ferric citrate in patients with nondialysis-dependent CKD and iron deficiency anemia. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 1851–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umanath, K.; Greco, B.; Jalal, D.I.; McFadden, M.; Sika, M.; Koury, M.J.; Niecestro, R.; Hunsicker, L.G.; Greene, T.; Lewis, J.B.; et al. The safety of achieved iron stores and their effect on iv iron and ESA use: Post-hoc results from a randomized trial of ferric citrate as phosphate binder in dialysis. Clin. Nephrol. 2017, 87, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtaszek, E.; Glogowski, T.; Malyszko, J. Iron and chronic kidney disease: Still a challenge. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 565135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisani, A.; Riccio, E.; Sabbatini, M.; Andreucci, M.; Del Rio, A.; Visciano, B. Effect of oral liposomal iron versus intravenous iron for treatment of iron deficiency anaemia in CKD patients: A randomized trial. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2015, 30, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbane, S.N.; Singh, A.K.; Cournoyer, S.H.; Jindal, K.K.; Fanti, P.; Guss, C.D.; Lin, V.H.; Pratt, R.D.; Gupta, A. Ferric pyrophosphate citrate (Triferic™) administration via the dialysate maintains hemoglobin and iron balance in chronic hemodialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2015, 30, 2019–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdougall, I.C.; Comin-Colet, J.; Breymann, C.; Spahn, D.R.; Koutroubakis, I.E. Iron sucrose: A wealth of experience in treating iron deficiency. Adv. Ther. 2020, 37, 1960–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, P.A.; Bhandari, S.; Saxena, S.; Agarwal, D.; Wirtz, G.; Kletzmayr, J.; Thomsen, L.L.; Coyne, D.W. A randomized trial of iron isomaltoside 1000 versus oral iron in non-dialysis dependent chronic kidney disease patients with anaemia. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2016, 31, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, S.D.; Gaillard, C.A.; Bock, A.H.; Carrera, F.; Eckardt, K.U.; Van Wyck, D.B.; Cronin, M.; Meier, Y.; Larroque, S.; Macdougall, I.C.; et al. Safety of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose versus oral iron in patients with nondialysis-dependent CKD: An analysis of the 1-year FIND-CKD trial. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2017, 32, 1530–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdougall, I.C.; White, C.; Anker, S.D.; Bhandari, S.; Farrington, K.; Kalra, P.A.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Murray, H.; Tomson, C.R.V.; Wheeler, D.C.; et al. Intravenous Iron in Patients Undergoing Maintenance Hemodialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdougall, I.C.; Strauss, W.E.; McLaughlin, J.; Li, Z.; Dellanna, F.; Hertel, J. A randomized comparison of ferumoxytol and iron sucrose for treating iron deficiency anemia in patients with CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 9, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdougall, I.C.; Strauss, W.E.; Dahl, N.V.; Bernard, K.; Li, Z. Ferumoxytol for iron deficiency anemia in patients undergoing hemodialysis. The FACT randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nephrol. 2019, 91, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, B.; Tobiasch, M.; Viveiros, A.; Tilg, H.; Kennedy, N.A.; Wolf, M.; Zoller, H. Hypophosphataemia after treatment of iron deficiency with intravenous ferric carboxymaltose or iron isomaltoside-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 2256–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheetz, M.; Barrington, P.; Callies, S.; Berg, P.H.; MbColm, J.; Marbury, T.; Decker, B.; Dyas, G.L.; Truhlar, S.M.E.; Benschop, R.; et al. Targeting the hepcidin-ferroportin pathway inanemia of chronic kidney disease. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 85, 935–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rhee, F.; Fayad, L.; Voorhees, P.; Furman, R.; Lonial, S.; Borghaei, H.; Furman, R.; Lonial, S.; Borghaei, H.; Sokol, L.; et al. Siltuximab, a novel anti-interleukin-6 monoclonal antibody, for Castleman’s disease. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 3701–3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]