Oocyte Vitrification for Fertility Preservation in Women with Benign Gynecologic Disease: French Clinical Practice Guidelines Developed by a Modified Delphi Consensus Process

Abstract

:1. Introduction

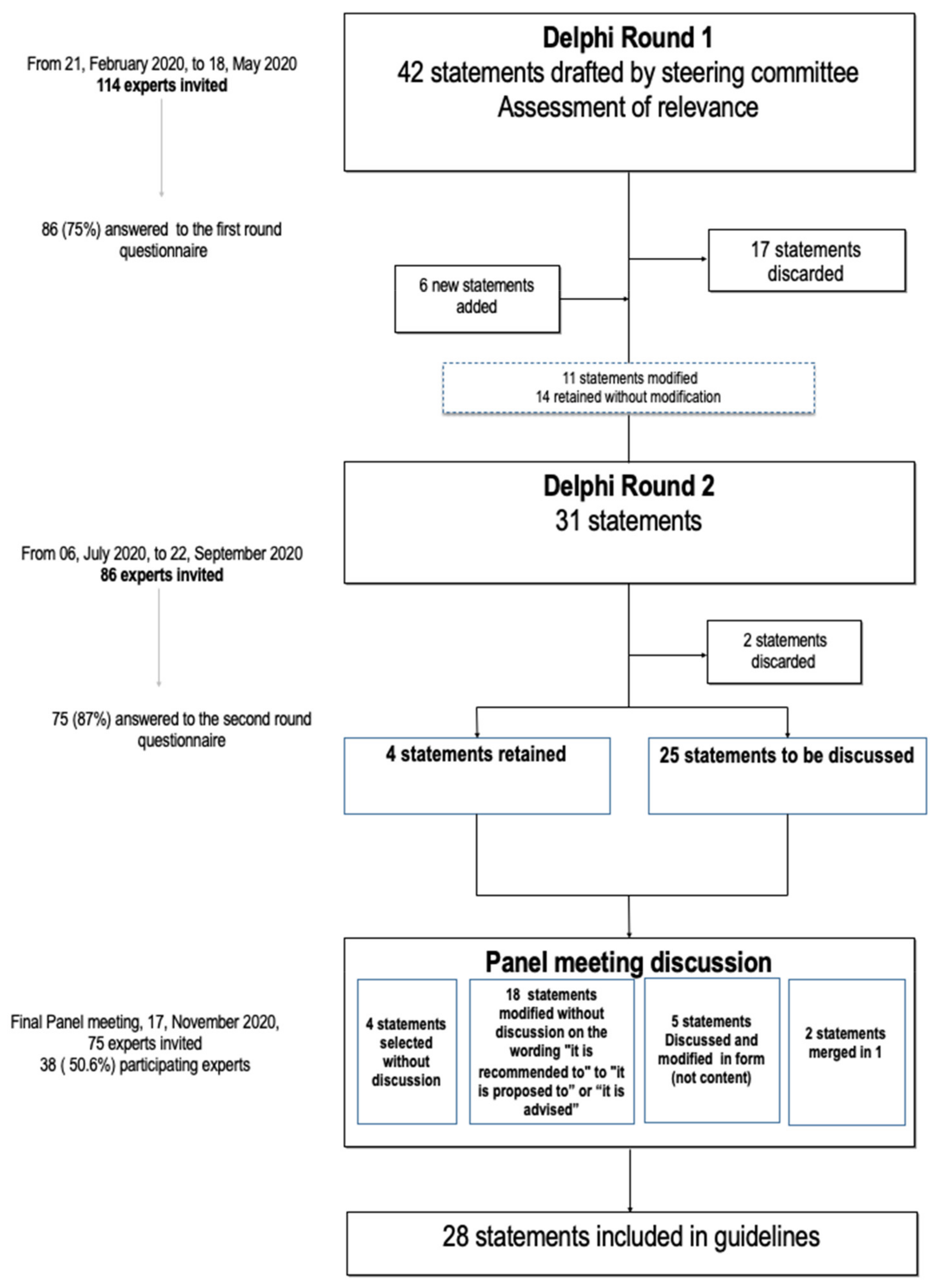

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preselection of Statements and Delphi Questionnaire Preparation

2.2. Expert Panel Composition

2.3. Delphi Round 1

2.4. Delphi Round 2

2.5. Final Meeting for Approval of Selected Clinical Guidelines

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Statements

3.2. Composition of the Expert Panels

3.2.1. Delphi Round 1

3.2.2. Delphi Round 2

3.2.3. Approval of Selected Clinical Guidelines

4. Discussion

4.1. Counseling Women of Reproductive Age with a Benign Gynecologic Disease

4.2. Technical Aspect of Fertility Preservation for BGD

4.3. Indications for FP in Endometriosis

4.4. Idiopathic Diminished Ovarian Reserve in the Absence of Gynecologic and Endocrinologic Diseases

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Panel Meeting Discussion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Proposed Items | Median | % ≥ 7 | Status | Modified Formulation (if Applicable) | Median | % ≥ 7 | Status | Consensus Formulation of the Final Retained Items |

| Counseling women of reproductive age with benign gynecologic disease about fertility preservation | ||||||||

| Before any surgery with a risk of ovarian damage, women of childbearing age must be informed of its potential effect on their ovarian reserve. | 9 | 95% | Modified | Before any surgery with a presumed risk of ovarian damage, women of childbearing age must be informed of its potential effect on their ovarian reserve. | 9 | 99% | Modified | Before any surgery at risk of ovarian damage, women of childbearing age should be informed of its potential effect on their ovarian reserve. |

| Women must be informed about the different techniques for fertility preservation. | 9 | 83% | Modified | Women must be informed about the techniques for fertility preservation most appropriate for them, according to their age and ovarian reserve. | 9 | 93% | Modified | Women should be informed about the techniques for preserving their fertility most appropriate for them, according to their age and ovarian reserve. |

| Women must be informed that the reuse of the preserved gametes may never be necessary. | 8 | 91% | Retained | 9 | 95% | Modified | Women should be informed that the use of the cryopreserved oocytes may never be necessary. | |

| Women must be informed of the possible complications associated with ovarian stimulation and with oocyte retrieval. | 9 | 86% | Retained | 9 | 96% | Modified | Women should be informed of the possible complications associated with ovarian stimulation and with oocyte retrieval. | |

| Women must be informed that fertility preservation techniques do not constitute a guarantee that they can have a child in the future. | 9 | 97% | Retained | 9 | 99% | Modified | Women should be informed that the use of fertility preservation techniques does not constitute a guarantee that they can have a child in the future. | |

| Women must be informed of the objective chances of having a child after oocyte vitrification according to the number of vitrified oocytes and their age at the time of vitrification. | 9 | 86% | Retained | 9 | 96% | Modified | Women should be informed of the objective chances of having a child after oocyte vitrification according to the number of vitrified oocytes and their age at the time of vitrification. | |

| It is advised that women be informed of the possibility of performing several cycles of stimulation to accumulate a sufficient number of oocytes. | 9 | 87% | Retained | 9 | 95% | Modified | Women should be informed of the possibility of performing several cycles of stimulation to accumulate a sufficient number of oocytes. | |

| It is advised to give women a waiting period to decide if they wish to launch themselves into the journey of fertility preservation. | 9 | 90% | Modified | It is advised to give women a waiting period to decide if they wish to commit themselves to the journey of fertility preservation. | 9 | 95% | Modified | Women should be given a reflection period to consider if they wish to commit themselves to the journey of fertility preservation. |

| Women who are candidates for fertility preservation must be informed of the legal and administrative conditions in force. | 9 | 88% | Retained | 9 | 93% | Modified and merged | A physician trained in reproductive medicine should inform the woman during a specific consultation about the techniques, modalities, results, and risks of fertility preservation, as well as of the regulatory conditions in effect in force. | |

| / | / | / | Added | A consultation with a specialist in reproductive medicine must take place to explain the techniques, modalities, results, and risks of fertility preservation. | 9 | 96% | ||

| / | / | / | Added | In the case of benign gynecologic disease for which there is a risk that treatment might impair fertility, women must be informed about the conditions of access to fertility preservation and time required for it. | 9 | 95% | Modified | Women with a benign gynecologic disease for which there is a risk that treatment might impair fertility should be informed about the desirable timeframe for implementing the appropriate fertility preservation procedures. |

| Practical aspects of fertility preservation for benign gynecologic disease | ||||||||

| It is advised to prefer vitrification of mature oocytes after ovarian stimulation. | 9 | 97% | Retained | 9 | 97% | Modified | Vitrification of mature oocytes after ovarian stimulation is the preferred method of fertility preservation for benign gynecologic disease. | |

| It is advised to propose 37 years as the maximum age at which oocyte preservation should be offered. | 5 | 25% | Discarded | / | / | / | / | / |

| It is advised to propose 40 years as the maximum age at which oocyte preservation should be offered. | 6 | 40% | Discarded | / | / | / | / | / |

| It is not advised to perform fertility preservation for benign gynecologic disease when the biomarkers (FSH and blood estradiol at the beginning of the follicular phase, and AMH) and ultrasound (antral follicle count) already show a severely diminished ovarian reserve. | 5 | 33% | Discarded | / | / | / | / | / |

| It is advised to await the age of 23 years before proposing oocyte cryopreservation because of the higher risk of oocyte aneuploidy among very young women. | 4 | 25% | Discarded | / | / | / | / | / |

| It is advised to await if possible the age of 18 years before proposing oocyte cryopreservation because of the higher risk of oocyte aneuploidy among very young women. | 5 | 35% | Discarded | / | / | / | / | / |

| Indications for fertility preservation for endometriosis | ||||||||

| It is advised to propose fertility preservation for bilateral endometriomas > 3 cm. | 9 | 79% | Retained | 9 | 85% | Modified | Fertility preservation should be proposed for bilateral endometriomas > 3 cm. | |

| It is advised to propose fertility preservation for voluminous unilateral endometrioma. | 7 | 52% | Discarded | / | / | / | / | / |

| It is advised to propose fertility preservation for unilateral endometrioma ≥ 6 cm. | 7 | 53% | Discarded | / | / | / | / | / |

| It is not advised to envision fertility preservation for a first episode of unilateral endometrioma < 3 cm. | 8 | 65% | Modified | It is not advised to envision fertility preservation for a first episode of unilateral endometriomas < 3 cm in a woman with an ovarian reserve normal for her age. | 8 | 84% | Modified | It is not advised to propose fertility preservation for a first episode of unilateral endometrioma < 3 cm in a woman with an ovarian reserve normal for her age. |

| In the case of a first episode of unilateral endometrioma between 3 and 6 cm, it is advised to assess the indication for fertility preservation on a case-by-case basis according to age and ovarian reserve. | 9 | 77% | Retained | 9 | 89% | Modified | For a first episode of unilateral endometrioma > 3 cm, it is advised to assess the indication for fertility preservation on a case-by-case basis according to age and ovarian reserve. | |

| It is advised to propose fertility preservation for multiple endometriomas > 3 cm on the same ovary. | 7 | 63% | Discarded | / | / | / | / | / |

| It is advised to propose fertility preservation for a recurrent unilateral endometrioma. | 8 | 79% | Retained | 8 | 88% | Modified | It is proposed to discuss fertility preservation for a recurrent unilateral endometrioma. | |

| It is advised to propose fertility preservation for an endometrioma on a single ovary. | 9 | 82% | Retained | 9 | 88% | Modified | It is advised to propose fertility preservation for an endometrioma on a single ovary. | |

| For a woman with no immediate plans to have a child, it is advised to propose fertility preservation if she had endometriosis that will require IVF should she want a child in the future. | 8 | 61% | Discarded | / | / | / | / | / |

| When it is decided that fertility preservation is indicated for endometrioma(s), it is advised to act if possible before surgery to increase the number of oocytes preserved. | 8 | 71% | Modified | When ovarian stimulation for fertility preservation is indicated for endometrioma(s), it is advised to act if possible before surgery to increase the number of oocytes preserved, if the ovaries are easily accessible for retrieval. | 8 | 85% | Modified | When ovarian stimulation for fertility preservation is indicated for endometrioma(s), it is proposed to act if possible before cystectomy to increase the number of oocytes cryopreserved, if the ovaries are easily accessible for retrieval. |

| It is advised to perform sclerotherapy of endometriomas before ovarian stimulation for oocyte preservation. | 5 | 24% | Discarded | / | / | / | / | / |

| It is not advised to propose fertility preservation for minimal to mild endometriosis. | 8 | 71% | Modified | It is not advised to propose fertility preservation for minimal to mild endometriosis that does not affect the ovaries. | 8 | 89% | Retained | It is not advised to propose fertility preservation for minimal to mild endometriosis that does not affect the ovaries. |

| It is not advised to propose fertility preservation for deep endometriosis with no tubal or ovarian damage. | 7 | 51% | Discarded | / | / | / | / | / |

| / | / | / | Added | When ovarian stimulation for fertility preservation is indicated for endometrioma(s), it is advised to perform it after drainage if the endometriomas are too bulky and/or prevent easy access to the ovaries for retrieval. | 8 | 82% | Modified | When ovarian stimulation for fertility preservation is indicated for endometrioma(s), drainage should be performed in first-line if the endometriomas are too bulky and/or if they prevent easy access to the ovaries for retrieval. |

| Other indications for fertility preservation for benign gynecologic disease: tubal disease, persistent ovarian cysts, fibroids | ||||||||

| It is advised to propose fertility preservation in the case of severe tubal impairment for which IVF will be probably necessary if pregnancy should be desired. | 5 | 36% | Discarded | / | / | / | / | / |

| It is not advised to propose fertility preservation before surgery for a first persistent unilateral non-endometriotic ovarian cyst episode. | 8 | 76% | Retained | 8 | 88% | Retained | It is not advised to propose fertility preservation before surgery for a first persistent unilateral non-endometriotic ovarian cyst episode. | |

| It is advised to discuss fertility preservation for a first bilateral persistent ovarian cyst episode. | 8 | 73% | Modified | It is advised to discuss fertility preservation if surgery is indicated for bilateral persistent ovarian cysts, depending on age and ovarian reserve. | 8.5 | 89% | Modified | It is proposed to discuss fertility preservation if surgery is indicated for bilateral persistent ovarian cysts, depending on age and ovarian reserve. |

| Fertility preservation must not be proposed for isolated uterine adenomyosis. | 8 | 86% | Retained | 9 | 94% | Modified | Fertility preservation is not proposed for isolated uterine adenomyosis. | |

| After adnexal torsion, it is advised to discuss fertility preservation on a case-by-case basis. | 7 | 58% | Discarded | / | / | / | / | / |

| Fertility preservation must not be proposed in the case of a single ovary with no disease at risk of diminished ovarian reserve associated with the procedure. | 7 | 56% | Discarded | / | / | / | / | / |

| Fertility preservation must be proposed in cases of presumed benign persistent ovarian cyst(s) on a single ovary. | 7 | 67% | Modified | It is advised to discuss fertility preservation if surgery is indicated for presumed benign persistent ovarian cyst(s) on single ovary, depending on age and ovarian reserve. | 8 | 90% | Modified | It is proposed to discuss fertility preservation if surgery is indicated for presumed benign persistent ovarian cyst(s) on a single ovary. |

| Fertility preservation must be proposed after surgery for a recurrent persistent ovarian cysts presumed to be benign. | 8 | 73% | Modified | It is advised to discuss fertility preservation if surgery is indicated for a recurrent benign persistent ovarian cyst(s), depending on age and ovarian reserve. | 9 | 92% | Modified | It is proposed to discuss fertility preservation if surgery is indicated for recurrent benign persistent ovarian cyst(s), depending on age and ovarian reserve. |

| Fertility preservation must not be proposed for isolated fibromatous disease. | 8 | 81% | Retained | 8 | 89% | Modified | It is not advised to propose fertility preservation for isolated fibromatous disease. | |

| Fertility preservation is advised when embolization of uterine fibromas is indicated in a woman of childbearing age. | 5 | 36% | Discarded | / | / | / | / | / |

| / | / | / | Added | In the case of surgery for benign gynecologic disease at presumed risk of impaired ovarian function, preoperative ovarian reserve testing is proposed. | 9 | 90% | Retained | In the case of surgery for benign gynecologic disease at presumed risk of impaired ovarian function, preoperative ovarian reserve testing is proposed. |

| / | / | / | Added | In the case of surgery for persistent benign ovarian cysts except for endometrioma (dermoid, seromucinous, etc.) when fertility preservation is indicated, it is advised to proceed to oocyte preservation after ovarian surgery. | 7 | 55% | Discarded | / |

| / | / | / | Added | When embolization of uterine fibromas is indicated as an alternative to hysterectomy, it is proposed that oocyte preservation be discussed as a function of age and ovarian reserve. | 7 | 51% | Discarded | / |

| Fertility preservation for idiopathic ovarian reserve in the absence of gynecologic and endocrinologic diseases | ||||||||

| It is advised to discuss fertility preservation for women with a first-degree family history of premature ovarian insufficiency. | 7 | 67% | Modified | For women with a first-degree family history of premature ovarian insufficiency, it is advised to perform regular follow-up of their ovarian reserve to be able to propose fertility preservation if necessary. | 8 | 82% | Retained | For women with a first-degree family history of premature ovarian insufficiency, it is advised to perform regular follow-up of their ovarian reserve to be able to propose fertility preservation if necessary. |

| It is advised not to propose cryopreservation of ovarian tissue for a woman referred for consultation about fertility preservation for a diminished ovarian reserve. | 7 | 55% | Discarded | / | / | / | / | / |

| Should an abnormally diminished ovarian reserve be discovered fortuitously, it is advised to discuss fertility preservation on a case-by-case basis in cooperation with geneticists. | 8 | 78% | Modified | Should a severe impairment of ovarian reserve for age be discovered fortuitously and indicate the need for an etiological workup, it is advised to discuss fertility preservation on a case-by-case basis as a function of the results of the genetic workup. | 9 | 89% | Modified | Should a substantial impairment of ovarian reserve for age be discovered fortuitously and indicate the need for an etiological workup, it is proposed to discuss fertility preservation on a case-by-case basis. |

| Should a diminished AMH level be discovered fortuitously a single time, it is not recommended to propose fertility preservation. | 6 | 42% | Discarded | / | / | / | / | / |

References

- Oktay, K.; Harvey, B.E.; Partridge, A.H.; Quinn, G.P.; Reinecke, J.; Taylor, H.S.; Wallace, W.H.; Wang, E.T.; Loren, A.W. Fertility Preservation in Patients with Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1994–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESHRE Guideline Group on Female Fertility Preservation; Anderson, R.A.; Amant, F.; Braat, D.; D’Angelo, A.; Lopes, S.M.C.d.S.; Demeestere, I.; Dwek, S.; Frith, L.; Lambertini, M.; et al. ESHRE Guideline: Female Fertility Preservation. Hum. Reprod. Open 2020, 2020, hoaa052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, K.; Bedoschi, G.; Berkowitz, K.; Bronson, R.; Kashani, B.; McGovern, P.; Pal, L.; Quinn, G.; Rubin, K. Fertility Preservation in Women with Turner Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review and Practical Guidelines. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2016, 29, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Decanter, C.; d’Argent, E.M.; Boujenah, J.; Poncelet, C.; Chauffour, C.; Collinet, P.; Santulli, P. Endometriosis and fertility preservation: CNGOF-HAS Endometriosis Guidelines. Gynecol. Obstet. Fertil. Senol. 2018, 46, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantsberg, D.; Fernando, S.; Cohen, Y.; Rombauts, L. The Role of Fertility Preservation in Women with Endometriosis: A Systematic Review. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020, 27, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somigliana, E.; Vercellini, P. Fertility Preservation in Women with Endometriosis: Speculations Are Finally over, the Time for Real Data Is Initiated. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 113, 765–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulkedid, R.; Abdoul, H.; Loustau, M.; Sibony, O.; Alberti, C. Using and Reporting the Delphi Method for Selecting Healthcare Quality Indicators: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, H. Endometriosis Surgery and Preservation of Fertility, What Surgeons Should Know. J. Visc. Surg. 2018, 155, S31–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoop, D. Oocyte Vitrification for Elective Fertility Preservation: Lessons for Patient Counseling. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 105, 603–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grynberg, M.; Sermondade, N. Fertility Preservation: Should We Reconsider the Terminology? Hum. Reprod. 2019, 34, 1855–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, A.; García-Velasco, J.; Domingo, J.; Pellicer, A.; Remohí, J. Elective and Onco-Fertility Preservation: Factors Related to IVF Outcomes. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 2222–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandone, E.; Di Micco, P.P.; Villani, M.; Colaizzo, D.; Fernández-Capitán, C.; Del Toro, J.; Rosa, V.; Bura-Riviere, A.; Quere, I.; Blanco-Molina, Á.; et al. Venous Thromboembolism in Women Undergoing Assisted Reproductive Technologies: Data from the RIETE Registry. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 118, 1962–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, J.O.; Richter, K.S.; Lim, J.; Stillman, R.J.; Graham, J.R.; Tucker, M.J. Successful Elective and Medically Indicated Oocyte Vitrification and Warming for Autologous in Vitro Fertilization, with Predicted Birth Probabilities for Fertility Preservation According to Number of Cryopreserved Oocytes and Age at Retrieval. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 105, 459–466.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- ETIC Endometriosis Treatment Italian Club. When More Is Not Better: 10 “don’ts” in Endometriosis Management. An ETIC* Position Statement. Hum. Reprod. Open 2019, 2019, hoz009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bafort, C.; Beebeejaun, Y.; Tomassetti, C.; Bosteels, J.; Duffy, J.M. Laparoscopic Surgery for Endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 10, CD011031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, A.; Giles, J.; Paolelli, S.; Pellicer, A.; Remohí, J.; García-Velasco, J.A. Oocyte Vitrification for Fertility Preservation in Women with Endometriosis: An Observational Study. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 113, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudice, L.C. Clinical Practice. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 2389–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleedoorn, M.J.; Velden, A.A.E.M.; Braat, D.D.M.; Peek, R.; Fleischer, K. To Freeze or Not to Freeze? An Update on Fertility Preservation In Females with Turner Syndrome. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Rev. 2019, 16, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K.B. Individual Fertility Assessment and Counselling in Women of Reproductive Age. Dan. Med. J. 2016, 63, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, E.G.; Ressler, I.B.; Young, S.; Batcheller, A.; Thomas, M.A.; DiPaola, K.B.; Rios, J. Postponing Childbearing and Fertility Preservation in Young Professional Women. South. Med. J. 2018, 111, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewailly, D.; Andersen, C.Y.; Balen, A.; Broekmans, F.; Dilaver, N.; Fanchin, R.; Griesinger, G.; Kelsey, T.W.; La Marca, A.; Lambalk, C.; et al. The Physiology and Clinical Utility of Anti-Mullerian Hormone in Women. Hum. Reprod. Update 2014, 20, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tehrani, F.R.; Solaymani-Dodaran, M.; Tohidi, M.; Gohari, M.R.; Azizi, F. Modeling Age at Menopause Using Serum Concentration of Anti-Mullerian Hormone. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dólleman, M.; Verschuren, W.M.M.; Eijkemans, M.J.C.; Broekmans, F.J.M.; van der Schouw, Y.T. Added Value of Anti-Müllerian Hormone in Prediction of Menopause: Results from a Large Prospective Cohort Study. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 1974–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lockwood, G.M. Social Egg Freezing: The Prospect of Reproductive “immortality” or a Dangerous Delusion? Reprod. Biomed. Online 2011, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Devenutto, L.; Quintana, R.; Quintana, T. In Vitro Activation of Ovarian Cortex and Autologous Transplantation: A Novel Approach to Primary Ovarian Insufficiency and Diminished Ovarian Reserve. Hum. Reprod. Open 2020, 2020, hoaa046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Round 1 (n = 86) n (%) | Round 2 (n = 75) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Status | ||

| Physicians | 80 (93) | 72 (96) |

| Patients | 6 (7) | 3 (4) |

| Age (median) (Q1–Q3) | 46 (37–54) (n = 81, 5 missing data) | 46 (41–54) (n = 74, 2 missing data) |

| If physicians, years of experience (range) | 17 (12–26) (n = 78, 2 missing data) | 16.5 (12–25.25) (n = 74, 2 missing data) |

| If physicians, specialty | ||

| Gynecology-obstetrics | 54 (63) | 46 (61) |

| Embryologist | 16 (19) | 16 (21) |

| Endocrinology | 5 (6) | 5 (7) |

| Radiology | 3 (3) | 3 (4) |

| Midwife | 2 (2) | 2 (3) |

| If physicians, field of activity | ||

| Physician specialized in reproductive medicine | 36 (45) | 30 (40) |

| Gynecologic surgeons | 20 (25) | 19 (25) |

| Embryologist | 15 (19) | 15 (20) |

| Endocrinology | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Other | 5 (6) | 4 (5) |

| Missing data | 3 (4) | 3 (4) |

| If physicians, sector of activity | ||

| Public sector | 48 (60) | 44 (61) |

| Private sector | 14 (18) | 10 (14) |

| Public and private sectors | 12 (15) | 12 (17) |

| Missing data | 6 (8) | 6 (8) |

| If physicians, activity in a University Teaching Hospital | 56 (70) | 52 (72) |

| Participation in a learning society of the field | 34 (39) | 34 (45) |

| Counseling Women of Reproductive Age with Benign Gynecologic Disease about Fertility Preservation | |

| 1 | Before any surgery at risk of ovarian damage, women of childbearing age should be informed of its potential effect on their ovarian reserve. |

| 2 | Women should be informed about the techniques for preserving their fertility most appropriate for them, according to their age and ovarian reserve. |

| 3 | Women should be informed that the use of the cryopreserved oocytes may never be necessary. |

| 4 | Women should be informed of the possible complications associated with ovarian stimulation and with oocyte retrieval. |

| 5 | Women should be informed that the use of fertility preservation techniques does not constitute a guarantee that they can have a child in the future. |

| 6 | Women should be informed of the objective chances of having a child after oocyte vitrification according to the number of vitrified oocytes and their age at the time of vitrification. |

| 7 | Women should be informed of the possibility of performing several cycles of stimulation to accumulate a sufficient number of oocytes. |

| 8 | Women should be given a reflection period to consider if they wish to commit themselves to the journey of fertility preservation. |

| 9 | A physician trained in reproductive medicine should inform the woman during a specific consultation about the techniques, modalities, results, and risks of fertility preservation, as well as of the regulatory conditions in effect in force. |

| 10 | Women with a benign gynecologic disease for which there is a risk that treatment might impair fertility should be informed about the desirable timeframe for implementing the appropriate fertility preservation procedures. |

| Practical aspects of fertility preservation for benign gynecologic disease | |

| 11 | Vitrification of mature oocytes after ovarian stimulation is the preferred method of fertility preservation for benign gynecologic disease. |

| Indications for fertility preservation for endometriosis | |

| 12 | Fertility preservation should be proposed for bilateral endometriomas > 3 cm. |

| 13 | It is not advised to propose fertility preservation for a first episode of unilateral endometrioma < 3 cm in a woman with an ovarian reserve normal for her age. |

| 14 | For a first episode of unilateral endometrioma > 3 cm, it is advised to assess the indication for fertility preservation on a case-by-case basis according to age and ovarian reserve. |

| 15 | It is proposed to discuss fertility preservation for a recurrent unilateral endometrioma. |

| 16 | It is advised to propose fertility preservation for an endometrioma on a single ovary. |

| 17 | When ovarian stimulation for fertility preservation is indicated for endometrioma(s), it is proposed to act if possible before cystectomy to increase the number of oocytes cryopreserved, if the ovaries are easily accessible for retrieval. |

| 18 | It is not advised to propose fertility preservation for minimal to mild endometriosis that does not affect the ovaries. |

| 19 | When ovarian stimulation for fertility preservation is indicated for endometrioma(s), drainage should be performed in first line if the endometriomas are too bulky and/or if they prevent easy access to the ovaries for retrieval. |

| Other indications for fertility preservation for benign gynecologic disease: tubal disease, persistent ovarian cysts, and fibroids | |

| 20 | It is not advised to propose fertility preservation before surgery for a first persistent unilateral non-endometriotic ovarian cyst episode. |

| 21 | It is proposed to discuss fertility preservation if surgery is indicated for bilateral persistent ovarian cysts, depending on age and ovarian reserve. |

| 22 | Fertility preservation is not proposed for isolated uterine adenomyosis. |

| 23 | It is proposed to discuss fertility preservation if surgery is indicated for presumed benign persistent ovarian cyst(s) on a single ovary. |

| 24 | It is proposed to discuss fertility preservation if surgery is indicated for recurrent benign persistent ovarian cyst(s), depending on age and ovarian reserve. |

| 25 | It is not advised to propose fertility preservation for isolated fibromatous disease. |

| 26 | In the case of surgery for benign gynecologic disease at presumed risk of impaired ovarian function, preoperative ovarian reserve testing is proposed. |

| Fertility preservation for idiopathic ovarian reserve in the absence of gynecologic and endocrinologic diseases | |

| 27 | For women with a first-degree family history of premature ovarian insufficiency, it is advised to perform regular follow-up of their ovarian reserve to be able to propose fertility preservation if necessary. |

| 28 | Should a substantial impairment of ovarian reserve for age be discovered fortuitously and indicate the need for an etiological workup, it is proposed to discuss fertility preservation on a case-by-case basis. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Courbiere, B.; Le Roux, E.; Mathieu d’Argent, E.; Torre, A.; Patrat, C.; Poncelet, C.; Montagut, J.; Gremeau, A.-S.; Creux, H.; Peigné, M.; et al. Oocyte Vitrification for Fertility Preservation in Women with Benign Gynecologic Disease: French Clinical Practice Guidelines Developed by a Modified Delphi Consensus Process. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3810. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10173810

Courbiere B, Le Roux E, Mathieu d’Argent E, Torre A, Patrat C, Poncelet C, Montagut J, Gremeau A-S, Creux H, Peigné M, et al. Oocyte Vitrification for Fertility Preservation in Women with Benign Gynecologic Disease: French Clinical Practice Guidelines Developed by a Modified Delphi Consensus Process. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(17):3810. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10173810

Chicago/Turabian StyleCourbiere, Blandine, Enora Le Roux, Emmanuelle Mathieu d’Argent, Antoine Torre, Catherine Patrat, Christophe Poncelet, Jacques Montagut, Anne-Sophie Gremeau, Hélène Creux, Maëliss Peigné, and et al. 2021. "Oocyte Vitrification for Fertility Preservation in Women with Benign Gynecologic Disease: French Clinical Practice Guidelines Developed by a Modified Delphi Consensus Process" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 17: 3810. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10173810

APA StyleCourbiere, B., Le Roux, E., Mathieu d’Argent, E., Torre, A., Patrat, C., Poncelet, C., Montagut, J., Gremeau, A.-S., Creux, H., Peigné, M., Chanavaz-Lacheray, I., Dirian, L., Fritel, X., Pouly, J.-L., Fauconnier, A., & on behalf of the PreFerBe Expert Panel. (2021). Oocyte Vitrification for Fertility Preservation in Women with Benign Gynecologic Disease: French Clinical Practice Guidelines Developed by a Modified Delphi Consensus Process. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(17), 3810. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10173810