Changes over Time in Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) Levels Predict Long-Term Survival Following Acute Myocardial Infarction among Patients with Diabetes Mellitus

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Data Sources and Classifications

2.3. Follow-Up and the Study Endpoint

2.4. HbA1C Values and Changes during the Follow-Up

2.5. Statistical Analysis

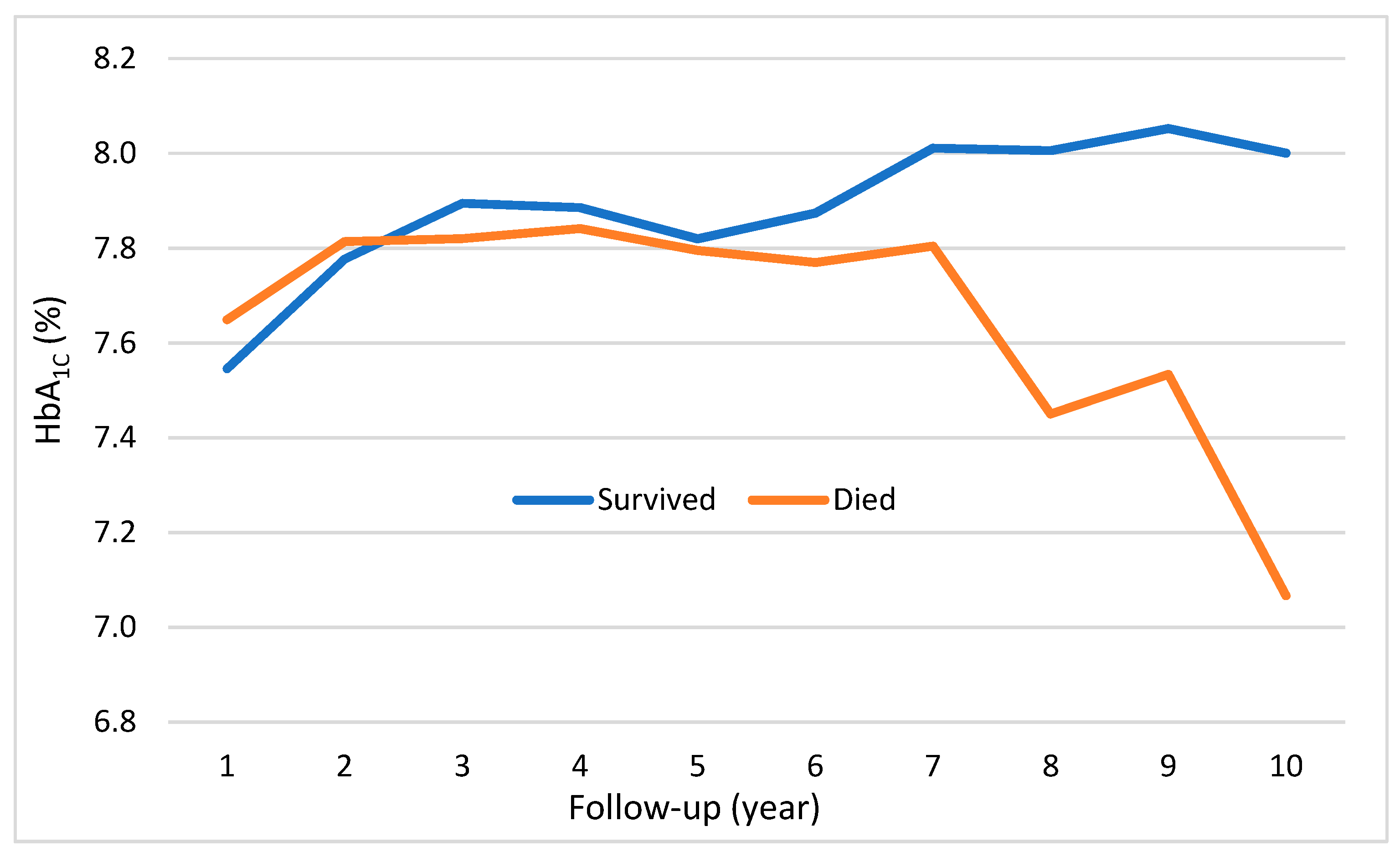

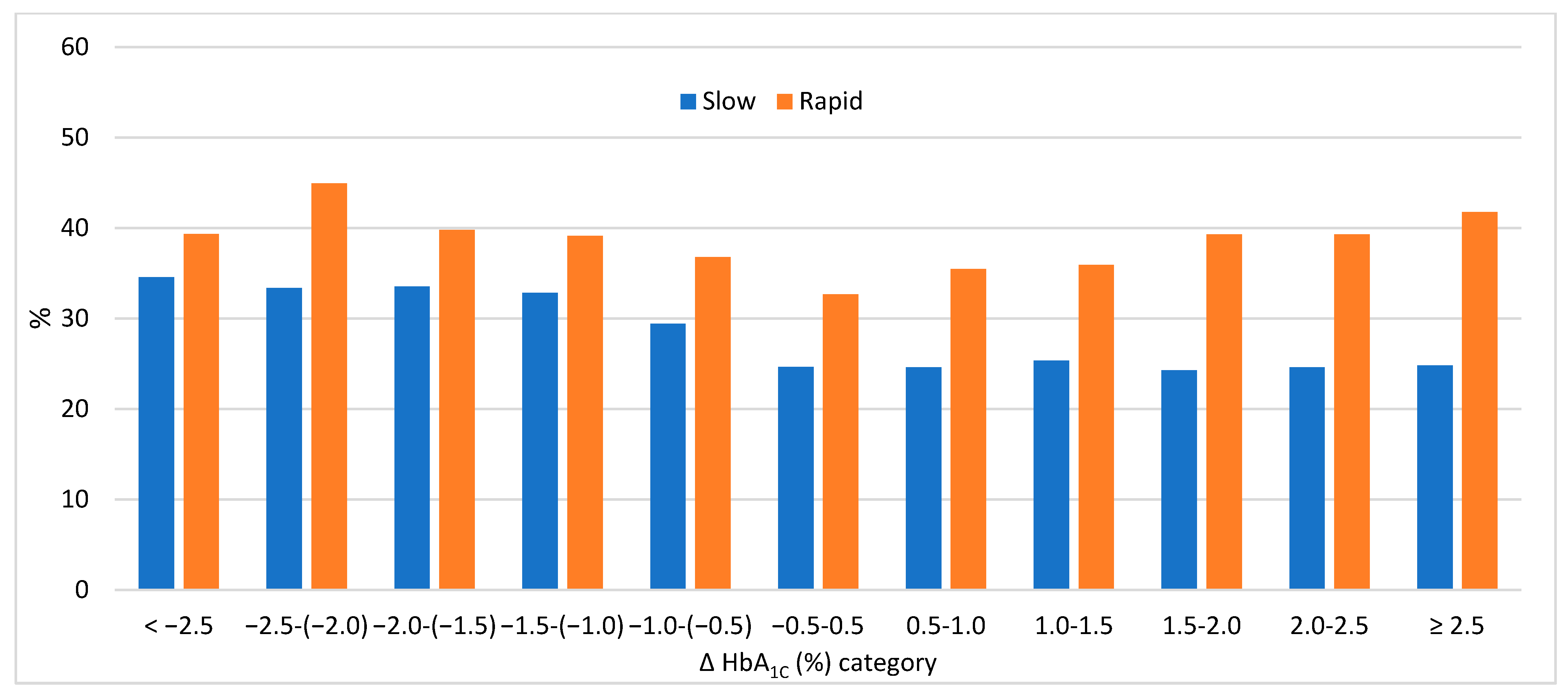

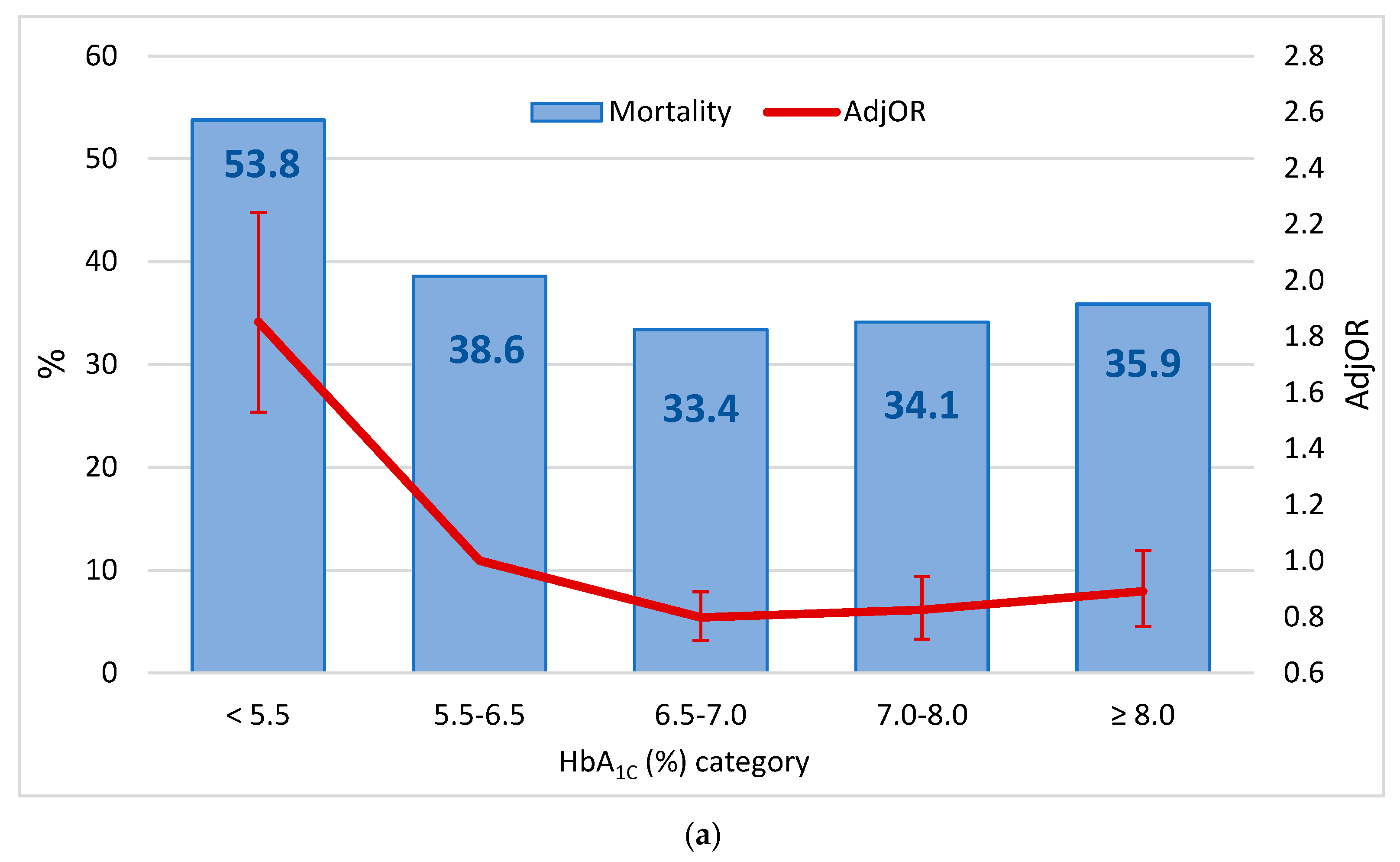

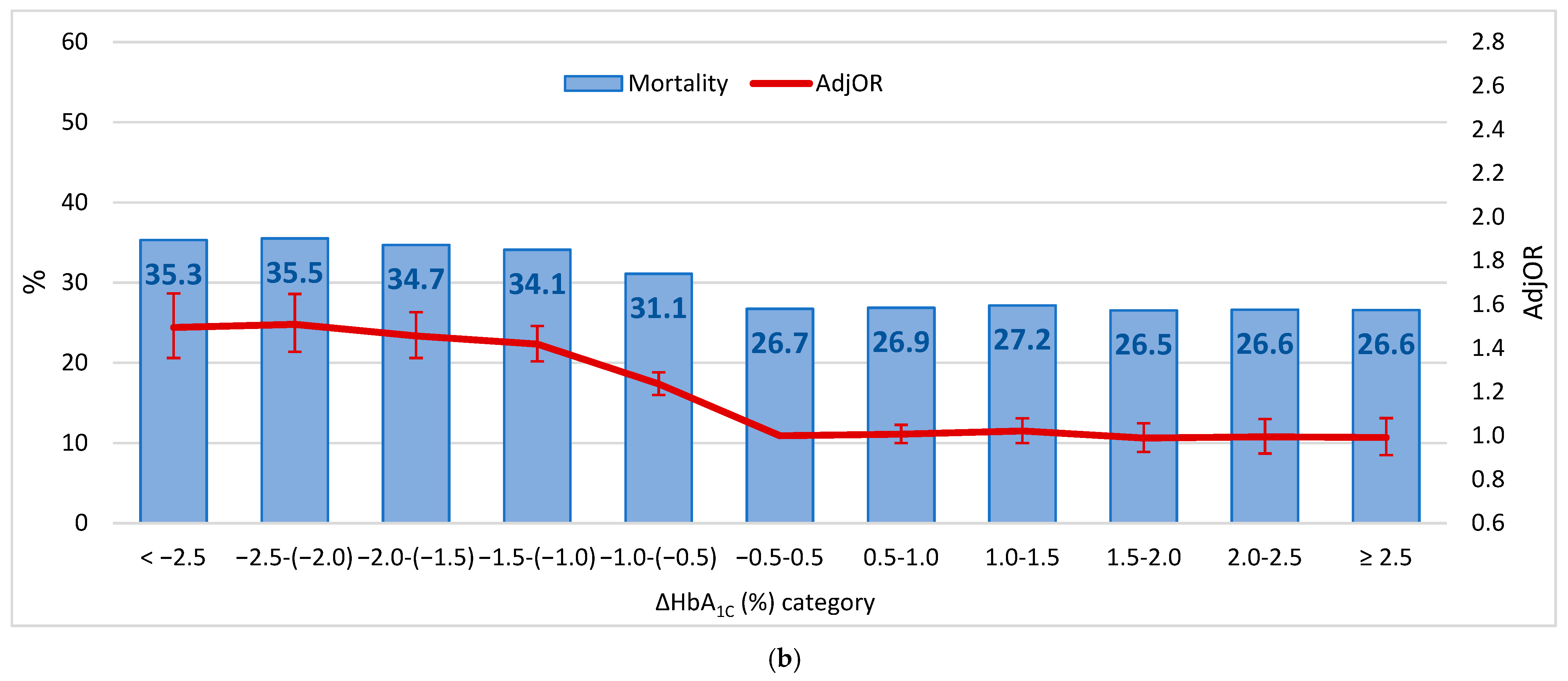

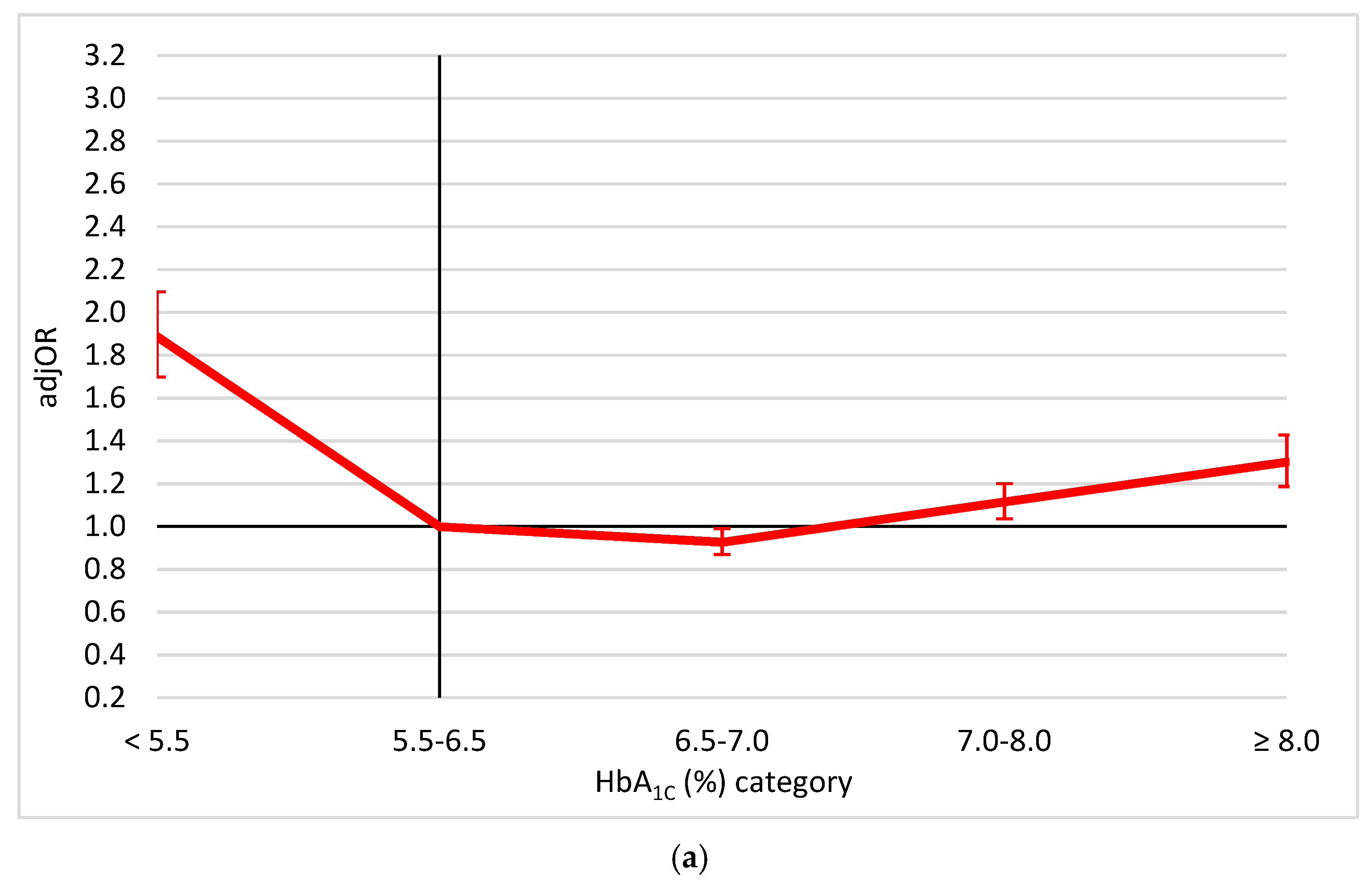

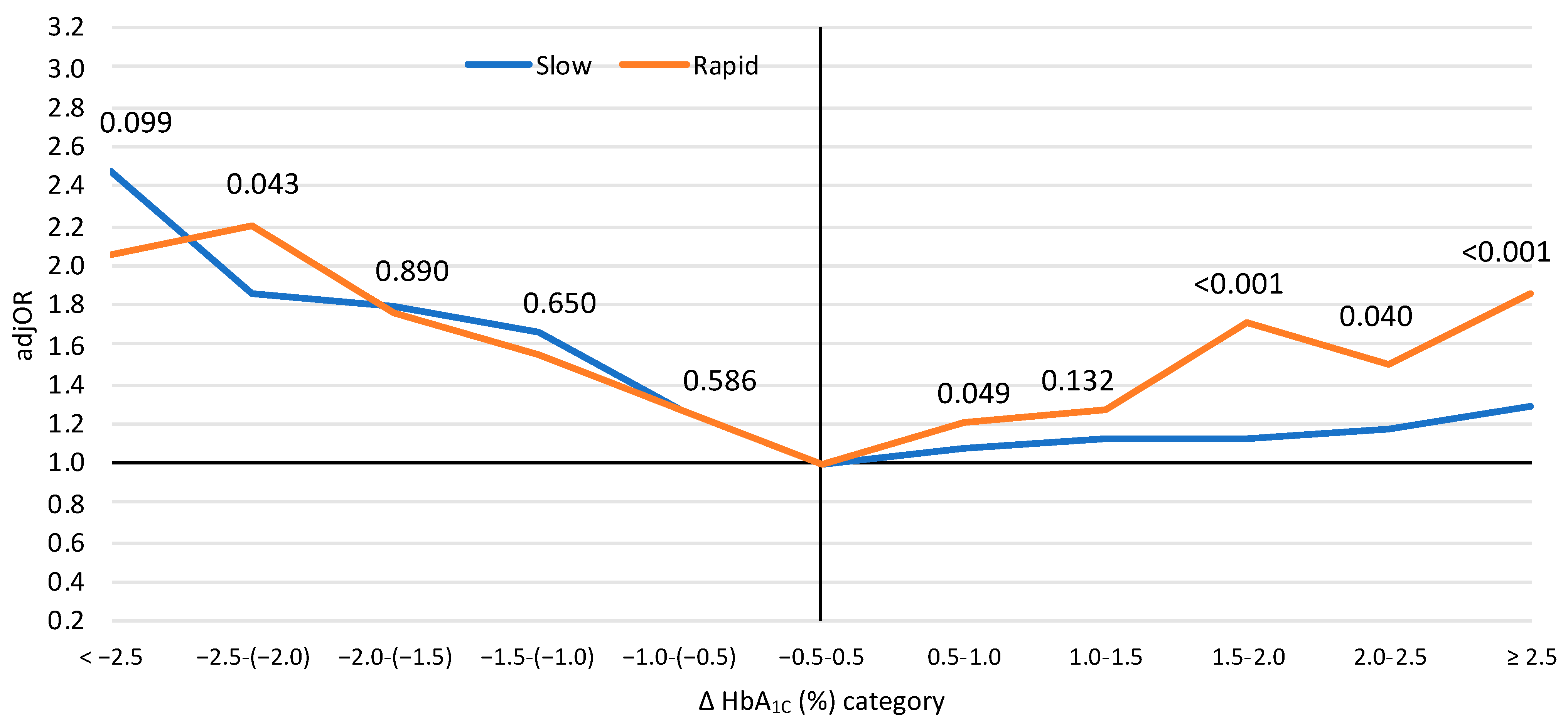

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Ezzati, M.; Obermeyer, Z.; Tzoulaki, I.; Mayosi, B.M.; Elliott, P.; Leon, D. Contributions of risk factors and medical care to cardiovascular mortality trends. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 508–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stevens, A.G.; The Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors of Chronic Diseases Collaborating Group (Body Mass Index); Singh, G.M.; Lu, Y.; Danaei, G.; Lin, J.K.; Finucane, M.M.; Bahalim, A.N.; McIntire, R.K.; Gutierrez, H.R.; et al. National, regional, and global trends in adult overweight and obesity prevalences. Popul. Health Metr. 2012, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Booth, G.L.; Kapral, M.K.; Fung, K.; Tu, J.V. Relation between age and cardiovascular disease in men and women with diabetes compared with non-diabetic people: A population-based retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2006, 368, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, R.R.; Paul, S.; Bethel, M.A.; Matthews, D.R.; Neil, H.A.W. 10-Year Follow-up of Intensive Glucose Control in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 1577–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olsson, M.; Schnecke, V.; Cabrera, C.; Skrtic, S.; Lind, M. Contemporary Risk Estimates of Three HbA1c Variables for Myocardial Infarction in 101,799 Patients Following Diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 1481–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shiyovich, A.; Gilutz, H.; Plakht, Y. Serum electrolyte/metabolite abnormalities among patients with acute myocardial infarction: Comparison between patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Postgrad. Med. 2020, 133, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammoud, T.; Tanguay, J.-F.; Bourassa, M.G. Management of coronary artery disease: Therapeutic options in patients with diabetes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 36, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Franklin, K.; Goldberg, R.J.; Spencer, F.; Klein, W.; Budaj, A.; Brieger, D.; Marre, M.; Steg, P.G.; Gowda, N.; Gore, J.M. Implications of Diabetes in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004, 164, 1457–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Plakht, Y.; Gilutz, H.; Shiyovich, A. Excess long-term mortality among hospital survivors of acute myocardial infarction. Soroka Acute Myocardial Infarction (SAMI) project. Public Health 2017, 143, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, G.; Zhang, T.; Yang, H.; Dai, W.; Tian, L.; Tao, H.; Mi, S.; Wang, T. Admission glycemic variability correlates with in-hospital outcomes in diabetic patients with non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2018, 19, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, P.J.; Cosentino, F. The 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD: New features and the ‘Ten Commandments’ of the 2019 Guidelines are discussed by Professor Peter J. Grant and Professor Francesco Cosentino, the Task Force chairmen. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 3215–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, R.; Reaven, P.D.; Emanuele, N.V.; VADT Investigators; Pothineni, N.V.; Wiitala, W.L.; Bahn, G.D.; Reda, D.J.; Ge, L.; McCarren, M.; et al. Follow-up of Glycemic Control and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 977–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, G.; Yuan, Z.; Chen, L. Glycosylated Hemoglobin in Relationship to Cardiovascular Outcomes and Death in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Nemeth, I.; Donnelly, L.; Hapca, S.; Zhou, K.; Pearson, E.R. Visit-to-Visit HbA1c Variability Is Associated with Cardiovascular Disease and Microvascular Complications in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2019, 43, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gorst, C.; Kwok, C.S.; Aslam, S.; Buchan, I.; Kontopantelis, E.; Myint, P.K.; Heatlie, G.; Loke, Y.; Rutter, M.K.; Mamas, M.A. Long-term Glycemic Variability and Risk of Adverse Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 2354–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Penno, G.; Solini, A.; Zoppini, G.; Orsi, E.; Fondelli, C.; Zerbini, G.; Morano, S.; Cavalot, F.; Lamacchia, O.; Trevisan, R.; et al. Hemoglobin A1c variability as an independent correlate of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional analysis of the Renal Insufficiency and Cardiovascular Events (RIACE) Italian Multicenter Study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2013, 12, 1–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Foo, V.; Quah, J.; Cheung, C.M.G.; Tan, N.-C.; Zar, K.L.M.; Chan, C.M.; Lamoureux, E.; Yin, W.T.; Tan, G.; Sabanayagam, C. HbA1c, systolic blood pressure variability and diabetic retinopathy in Asian type 2 diabetics. J. Diabetes 2016, 9, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takao, T.; Suka, M.; Yanagisawa, H.; Matsuyama, Y.; Iwamoto, Y. Predictive ability of visit-to-visit variability in HbA1c and systolic blood pressure for the development of microalbuminuria and retinopathy in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 2017, 128, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, C.-S.; Tian, J.; Miao, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Reaven, P.D.; Bloomgarden, Z.T.; Ning, G. Prognostic Significance of Long-term HbA1c Variability for All-Cause Mortality in the ACCORD Trial. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 1185–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Zhou, J.; Wong, W.T.; Liu, T.; Wu, W.K.K.; Wong, I.C.K.; Zhang, Q.; Tse, G. Glycemic and lipid variability for predicting complications and mortality in diabetes mellitus using machine learning. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2021, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Liu, T.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wong, W.T.; Tse, G. Predictions of diabetes complications and mortality using hba1c variability: A 10-year observational cohort study. Acta Diabetol. 2020, 58, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.; Kim, S.-H.; Yoon, C.-H.; Suh, J.-W.; Cho, Y.-S.; Youn, T.-J.; Chae, I.-H. Impact of Long-term Glycosylated Hemoglobin in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction: A retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plakht, Y.; Shiyovich, A.; Weitzman, S.; Fraser, D.; Zahger, D.; Gilutz, H. A new risk score predicting 1- and 5-year mortality following acute myocardial infarction Soroka Acute Myocardial Infarction (SAMI) Project. Int. J. Cardiol. 2012, 154, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmer, J.R.; Hoekstra, M.; Nijsten, M.W.; van der Horst, I.C.; Ottervanger, J.P.; Slingerland, R.J.; Dambrink, J.-H.E.; Bilo, H.J.G.; Zijlstra, F.; van’t Hof, A.W.J. Prognostic Value of Admission Glycosylated Hemoglobin and Glucose in Nondiabetic Patients With ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction Treated with Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Circulation 2011, 124, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lazzeri, C.; Valente, S.; Chiostri, M.; Attanà, P.; Mattesini, A.; Nesti, M.; Gensini, G.F. Glycated haemoglobin and long-term mortality in patients with ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2015, 16, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segar, M.W.; Patel, K.V.; Vaduganathan, M.; Caughey, M.C.; Butler, J.; Fonarow, G.C.; Grodin, J.L.; McGuire, D.K.; Pandey, A. Association of Long-term Change and Variability in Glycemia with Risk of Incident Heart Failure Among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Secondary Analysis of the ACCORD Trial. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 1920–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, A.P.; Fox, C.S.; McGuire, D.K.; Levitan, E.B.; Laclaustra, M.; Mann, D.M.; Muntner, P. Low Hemoglobin A1c and Risk of All-Cause Mortality Among US Adults Without Diabetes. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2010, 3, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kosiborod, M.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Goyal, A.; Krumholz, H.M.; Masoudi, F.A.; Xiao, L.; Spertus, J.A. Relationship Between Spontaneous and Iatrogenic Hypoglycemia and Mortality in Patients Hospitalized with Acute Myocardial Infarction. JAMA 2009, 301, 1556–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlstein, T.S.; Weuve, J.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Beckman, J. Red Blood Cell Distribution Width and Mortality Risk in a Community-Based Prospective Cohort. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, R.M.; Franco, R.S.; Khera, P.K.; Smith, E.P.; Lindsell, C.J.; Ciraolo, P.J.; Palascak, M.B.; Joiner, C.H. Red cell life span heterogeneity in hematologically normal people is sufficient to alter HbA1c. Blood 2008, 112, 4284–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monnier, L.; Mas, E.; Ginet, C.; Michel, F.; Villon, L.; Cristol, J.-P.; Colette, C. Activation of Oxidative Stress by Acute Glucose Fluctuations Compared With Sustained Chronic Hyperglycemia in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA 2006, 295, 1681–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ceriello, A.; Esposito, K.; Piconi, L.; Ihnat, M.A.; Thorpe, J.E.; Testa, R.; Boemi, M.; Giugliano, D. Oscillating Glucose Is More Deleterious to Endothelial Function and Oxidative Stress Than Mean Glucose in Normal and Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Diabetes 2008, 57, 1349–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Plakht, Y.; Greenberg, D.; Gilutz, H.; Arbelle, J.E.; Shiyovich, A. Mortality and healthcare resource utilization following acute myocardial infarction according to adherence to recommended medical therapy guidelines. Health Policy 2020, 124, 1200–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadén, J.; Forsblom, C.; Thorn, L.; Gordin, D.; Saraheimo, M.; Groop, P.-H.; The Finnish Diabetic Nephropathy Study Group. A1C Variability Predicts Incident Cardiovascular Events, Microalbuminuria, and Overt Diabetic Nephropathy in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes 2009, 58, 2649–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luk, A.O.Y.; Ma, R.C.V.; Lau, E.S.H.; Yang, X.; Lau, W.W.Y.; Yu, L.W.L.; Chow, F.C.C.; Chan, J.C.N.; So, W.-Y. Risk association of HbA1cvariability with chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: Prospective analysis of the Hong Kong Diabetes Registry. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2013, 29, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamer, M.; Stamatakis, E.; Kivimaki, M.; Kengne, A.P.; Batty, G. Psychological Distress, Glycated Hemoglobin, and Mortality in Adults with and Without Diabetes. Psychosom. Med. 2010, 72, 882–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Cromphaut, S. Hyperglycaemia as part of the stress response: The underlying mechanisms. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2009, 23, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathallah, N.; Slim, R.; Larif, S.; Hmouda, H.; Ben Salem, C. Drug-Induced Hyperglycaemia and Diabetes. Drug Saf. 2015, 38, 1153–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiafa, G.; Veneti, S.; Polychronopoulos, G.; Pilalas, D.; Daios, S.; Kanellos, I.; Didangelos, T.; Pagoni, S.; Savopoulos, C. Is HbA1c an ideal biomarker of well-controlled diabetes? Postgrad. Med. J. 2020, 97, 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipska, K.J.; Krumholz, H.M. Is Hemoglobin A1c the Right Outcome for Studies of Diabetes? JAMA 2017, 317, 1017–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Group | Survived | Died | Total | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 2264 | 1802 | 4066 | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, years: | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 62.18 (11.13) | 71.78 (10.61) | 66.44 (11.90) | <0.001 |

| <65 | 1401 (61.9) | 457 (25.4) | 1858 (45.7) | <0.001 |

| 65–75 | 568 (25.1) | 638 (35.4) | 1206 (29.7) | |

| ≥75 | 295 (13.0) | 707 (39.2) | 1002 (24.6) | |

| Sex: Male | 1613 (71.2) | 978 (54.3) | 2591 (63.7) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity: Arab/other | 579 (25.6) | 265 (14.7) | 844 (20.8) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac diseases | ||||

| Cardiomegaly | 164 (7.2) | 206 (11.4) | 370 (9.1) | <0.001 |

| Supraventricular arrhythmias | 230 (10.2) | 398 (22.1) | 628 (15.4) | <0.001 |

| CHF | 280 (12.4) | 542 (30.1) | 822 (20.2) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary heart disease | 125 (5.5) | 261 (14.5) | 386 (9.5) | <0.001 |

| CIHD | 2008 (88.7) | 1336 (74.1) | 3344 (82.2) | <0.001 |

| s/p MI | 201 (8.9) | 290 (16.1) | 491 (12.1) | <0.001 |

| s/p PCI | 325 (14.4) | 276 (15.3) | 601 (14.8) | 0.391 |

| s/p CABG | 195 (8.6) | 276 (15.3) | 471 (11.6) | <0.001 |

| AV block | 81 (3.6) | 99 (5.5) | 180 (4.4) | 0.003 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| Renal diseases | 96 (4.2) | 350 (19.4) | 446 (11.0) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 2021 (89.3) | 1516 (84.1) | 3537 (87.0) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1468 (64.8) | 1122 (62.3) | 2590 (63.7) | 0.09 |

| Obesity | 726 (32.1) | 418 (23.2) | 1144 (28.1) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 1020 (45.1) | 429 (23.8) | 1449 (35.6) | <0.001 |

| PVD | 219 (9.7) | 385 (21.4) | 604 (14.9) | <0.001 |

| Family history of IHD | 213 (9.4) | 33 (1.8) | 246 (6.1) | <0.001 |

| Other disorders | ||||

| COPD | 125 (5.5) | 202 (11.2) | 327 (8.0) | <0.001 |

| Neurological disorders | 310 (13.7) | 490 (27.2) | 800 (19.7) | <0.001 |

| Malignancy | 36 (1.6) | 97 (5.4) | 133 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Anemia | 892 (39.4) | 1148 (63.7) | 2040 (50.2) | <0.001 |

| GI bleeding | 26 (1.1) | 30 (1.7) | 56 (1.4) | 0.16 |

| Schizophrenia/Psychosis | 16 (0.7) | 40 (2.2) | 56 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol/drug addiction | 32 (1.4) | 23 (1.3) | 55 (1.4) | 0.707 |

| History of malignancy | 91 (4.0) | 122 (6.8) | 213 (5.2) | <0.001 |

| Characteristics of diabetes mellitus | ||||

| Type I | 18 (0.8) | 21 (1.2) | 39 (1.0) | 0.229 |

| Insulin-treated | 259 (11.4) | 185 (10.3) | 444 (10.9) | 0.233 |

| Complications: | ||||

| Non-complicated | 1923 (84.9) | 1338 (74.3) | 3261 (80.2) | <0.001 |

| Renal | 121 (5.3) | 171 (9.5) | 292 (7.2) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral circulation | 137 (6.1) | 271 (15.0) | 408 (10.0) | <0.001 |

| Ophthalmic | 128 (5.7) | 153 (8.5) | 281 (6.9) | <0.001 |

| Neurological | 91 (4.0) | 78 (4.3) | 169 (4.2) | 0.624 |

| Other | 11 (0.5) | 13 (0.7) | 24 (0.6) | 0.330 |

| Results of HbA1C tests (at baseline) | ||||

| HbA1C tests performance | 2035 (89.9) | 1557 (86.4) | 3592 (88.3) | 0.001 |

| HbA1C, %: Mean (SD) | 7.63 (1.69) | 7.68 (1.78) | 7.65 (1.73) | 0.456 |

| Clinical characteristics of the hospitalization | ||||

| Type of AMI: STEMI | 940 (41.5) | 564 (31.3) | 1504 (37.0) | <0.001 |

| Results of echocardiography | ||||

| Echocardiography performance | 1948 (86.0) | 1313 (72.9) | 3261 (80.2) | <0.001 |

| Severe LV dysfunction | 166 (8.5) | 221 (16.8) | 387 (11.9) | <0.001 |

| LV hypertrophy | 113 (5.8) | 116 (8.8) | 229 (7.0) | 0.001 |

| Mitral regurgitation | 64 (3.3) | 135 (10.3) | 199 (6.1) | <0.001 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation | 24 (1.2) | 82 (6.2) | 106 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 89 (4.6) | 192 (14.6) | 281 (8.6) | <0.001 |

| Results of angiography | ||||

| Angiography performance | 1897 (83.8) | 1043 (57.9) | 2940 (72.3) | <0.001 |

| Measure of CAD: | ||||

| None/non-significant | 72 (3.8) | 39 (3.7) | 111 (3.8) | <0.001 |

| One vessel | 456 (24.0) | 182 (17.4) | 638 (21.7) | |

| Two vessels | 543 (28.6) | 237 (22.7) | 780 (26.5) | |

| Three vessels/LM | 826 (43.5) | 585 (56.1) | 1411 (48.0) | |

| Type of treatment: | ||||

| Noninvasive | 245 (10.8) | 725 (40.2) | 970 (23.9) | <0.001 |

| PCI | 1581 (69.8) | 882 (48.9) | 2463 (60.6) | |

| CABG | 438 (19.3) | 195 (10.8) | 633 (15.6) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Plakht, Y.; Gilutz, H.; Shiyovich, A. Changes over Time in Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) Levels Predict Long-Term Survival Following Acute Myocardial Infarction among Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3232. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10153232

Plakht Y, Gilutz H, Shiyovich A. Changes over Time in Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) Levels Predict Long-Term Survival Following Acute Myocardial Infarction among Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(15):3232. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10153232

Chicago/Turabian StylePlakht, Ygal, Harel Gilutz, and Arthur Shiyovich. 2021. "Changes over Time in Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) Levels Predict Long-Term Survival Following Acute Myocardial Infarction among Patients with Diabetes Mellitus" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 15: 3232. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10153232

APA StylePlakht, Y., Gilutz, H., & Shiyovich, A. (2021). Changes over Time in Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) Levels Predict Long-Term Survival Following Acute Myocardial Infarction among Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(15), 3232. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10153232