Impact of Lipid Composition on Membrane Partitioning and Permeability of Gas Molecules

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Simulation Systems

2.2. Simulation Protocols

2.3. Membrane Partitioning and Permeability of Gases

3. Results

3.1. Variation of Membrane Structure by Lipid Composition

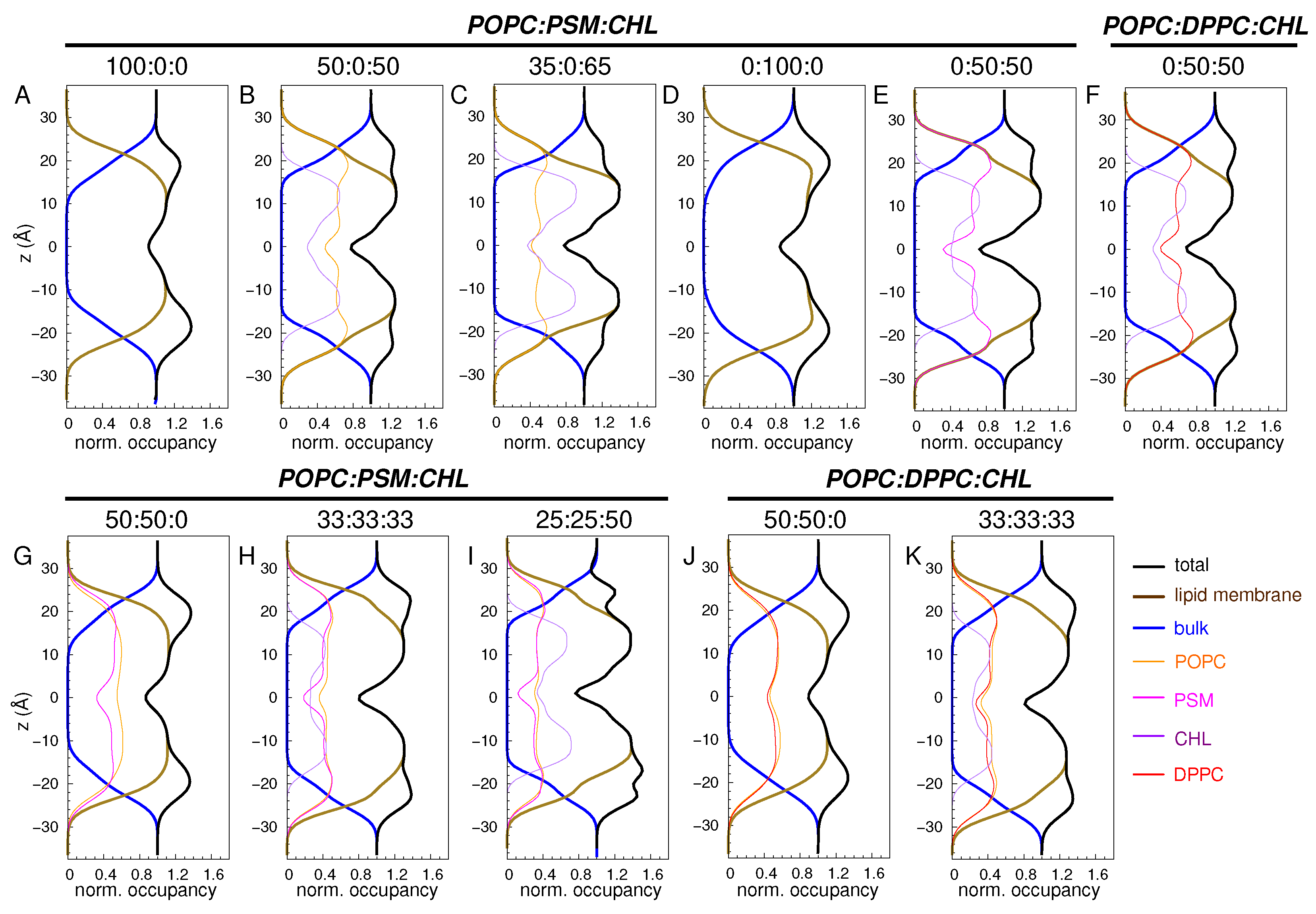

3.1.1. Occupancy Profiles

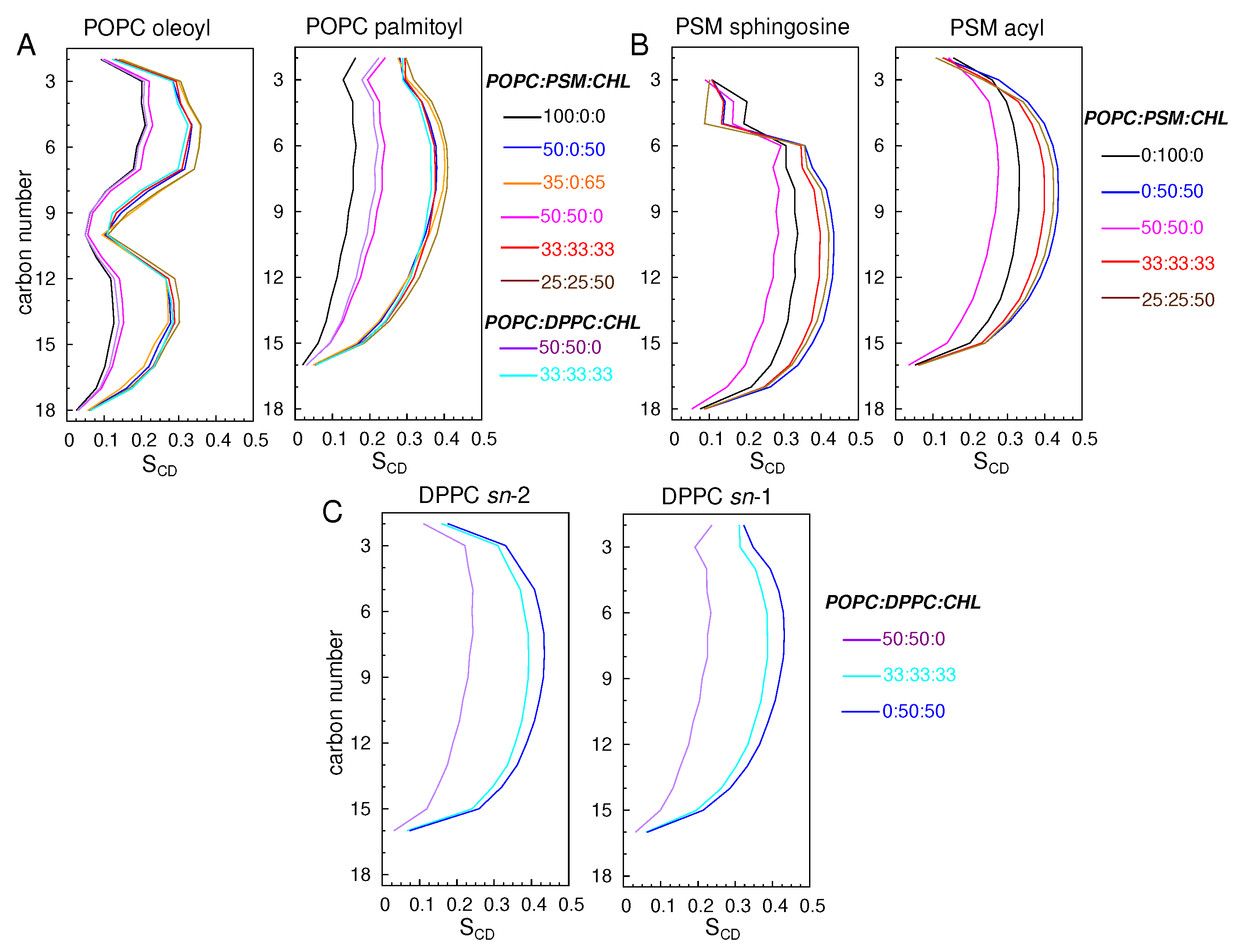

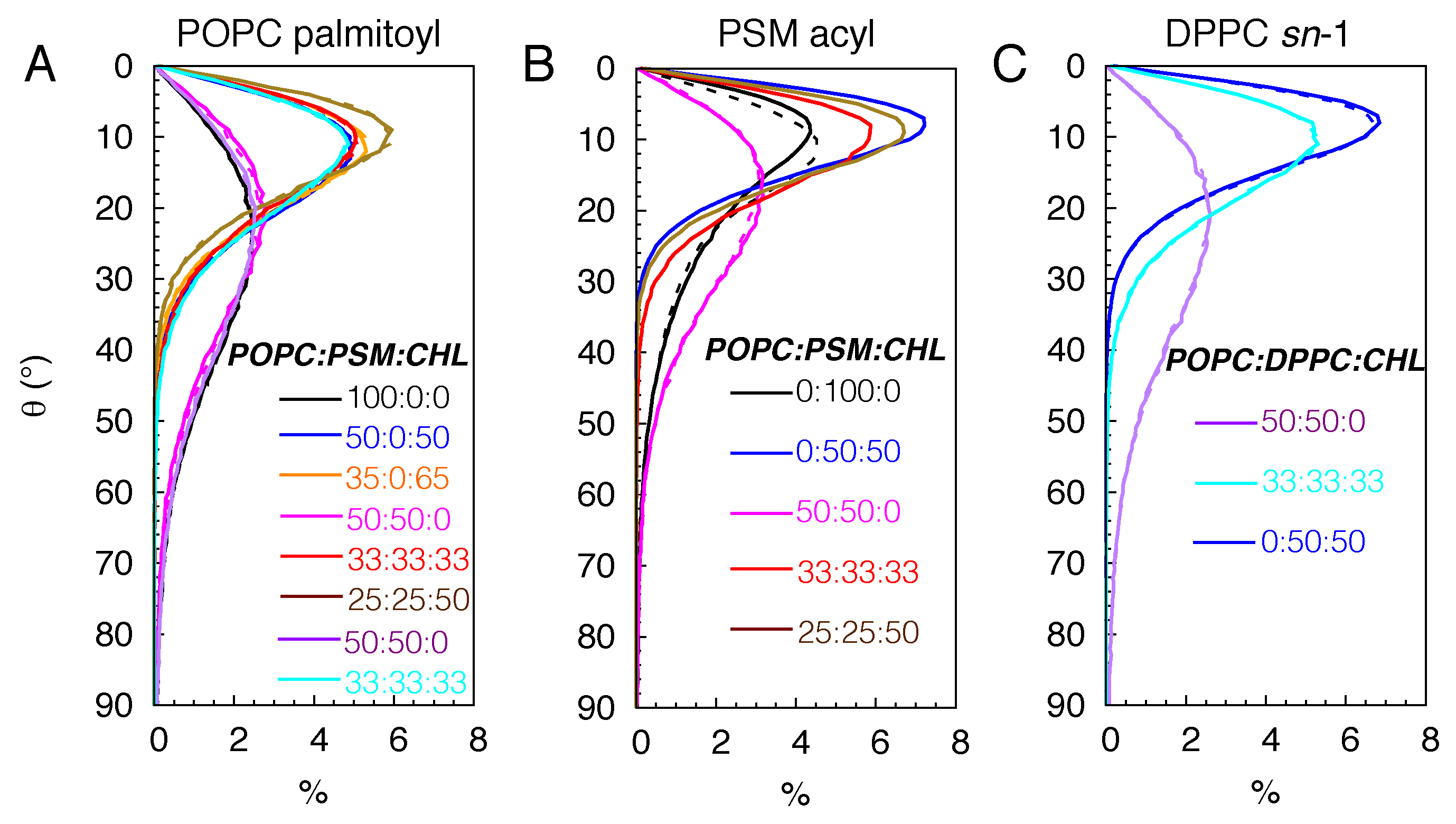

3.1.2. Lipid Ordering

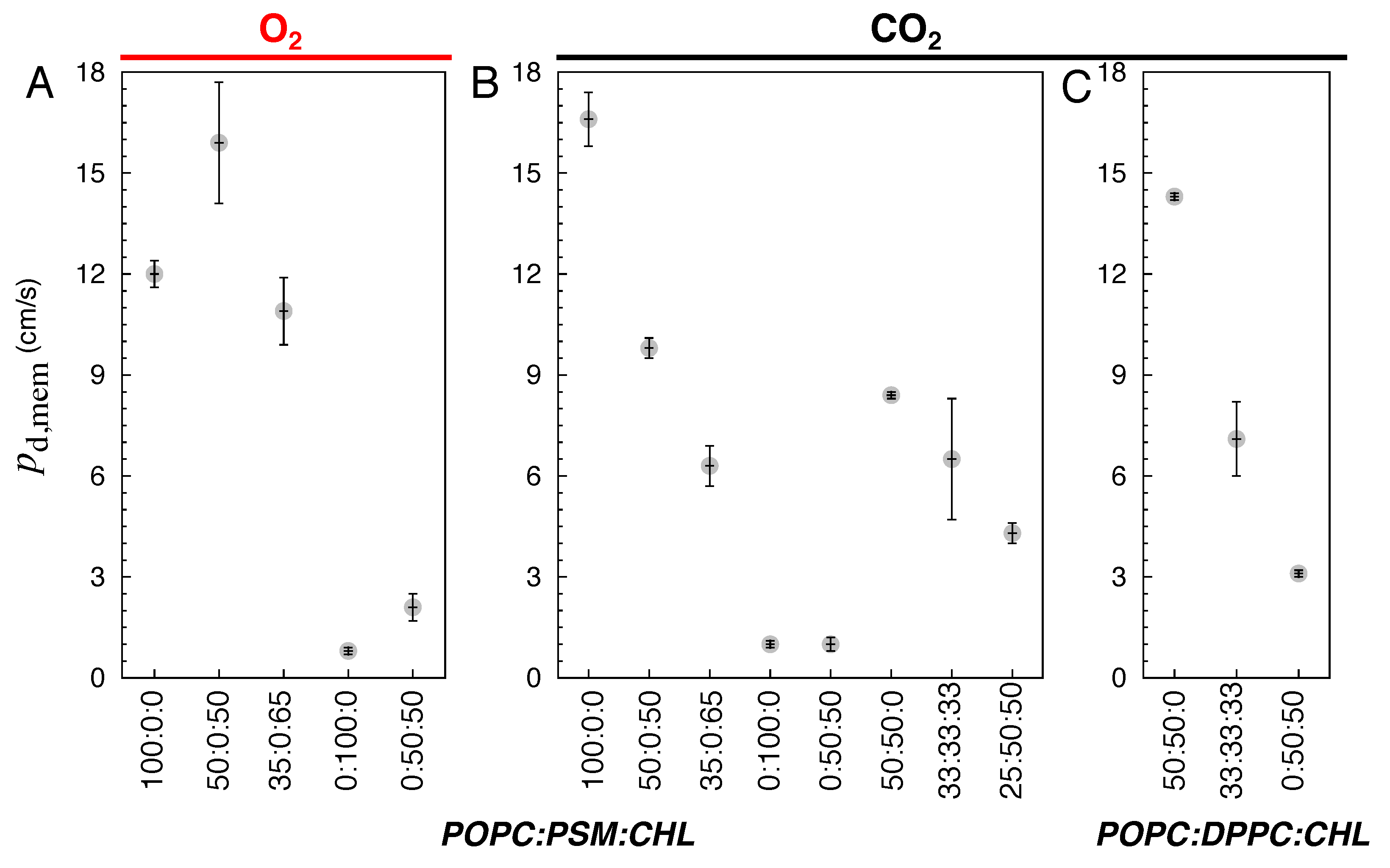

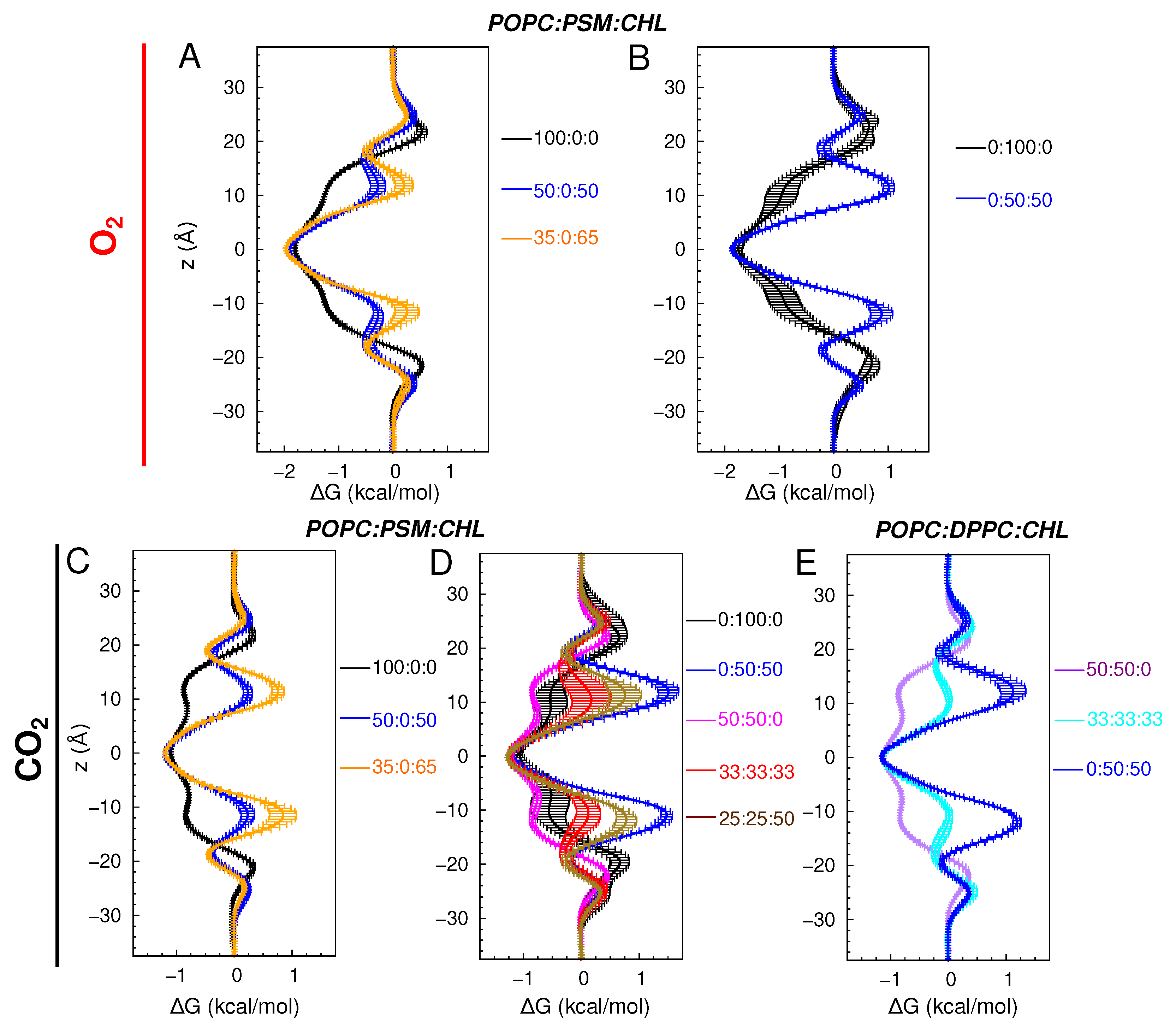

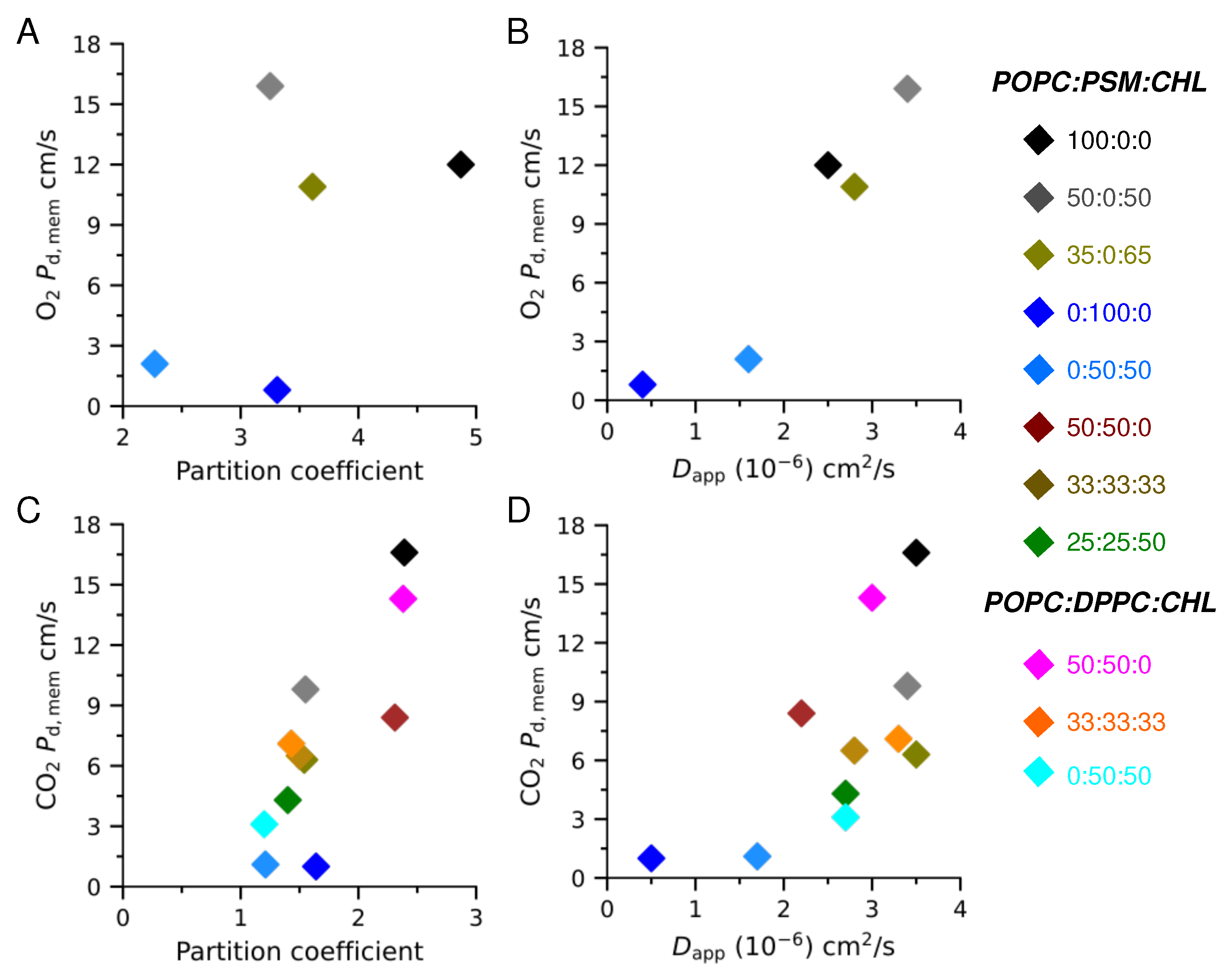

3.2. Membrane Partitioning and Permeability of Gas Molecules

3.2.1. Pure POPC and Binary POPC:CHL Bilayers

3.2.2. Special Cases of Pure PSM and Binary PSM:CHL Bilayers

3.2.3. POPC:PSM:CHL and POPC:DPPC:CHL Bilayers

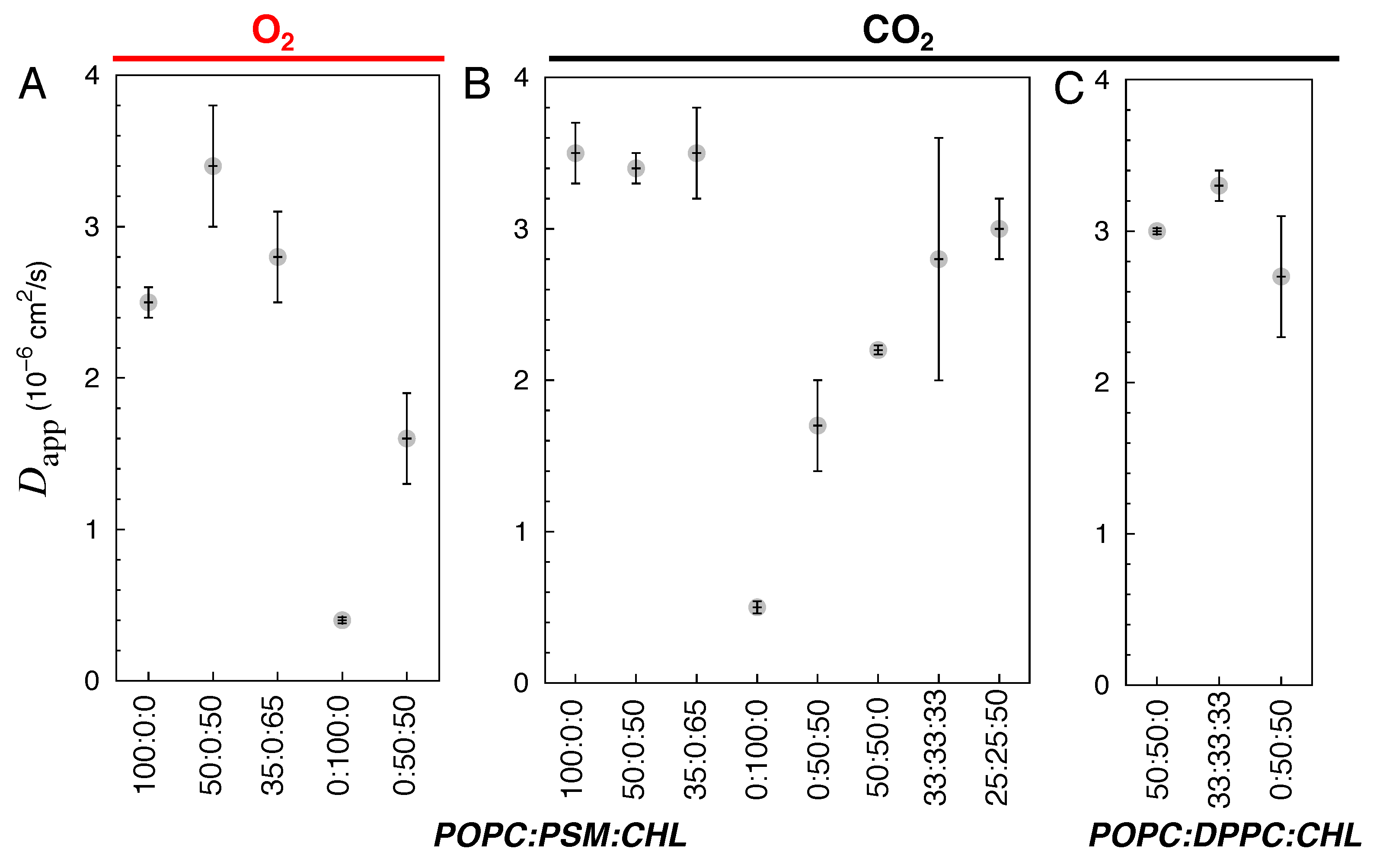

3.3. Diffusivity of Gas Molecules

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harayama, T.; Riezman, H. Understanding the Diversity of Membrane Lipid Composition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Meer, G.; Voelker, D.R.; Feigenson, G.W. Membrane Lipids: Where They Are and How They Behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrink, S.J.; Berendsen, H.J.C. Permeation Process of Small Molecules Across Lipid Membranes Studied by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 16729–16738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, J.L.; Bennett, W.F.D.; Tieleman, D.P. Distribution of Amino Acids in a Lipid Bilayer from Computer Simulations. Biophys. J. 2008, 94, 3393–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H.H. Zur Theorie Der Alkoholnarkose. Arch. Exp. Pathol. Pharmakol. 1899, 42, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, E. Über Die Osmotischen Eigenschaften Der Zelle in Ihrer Bedeutung Für Die Toxokologie Und Pharmakologie. Vjschr. Naturforsch. Ges. Zürich 1896, 41, 383. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Awqati, Q. One Hundred Years of Membrane Permeability: Does Overton Still Rule? Nat. Cell Biol. 1999, 1, E201–E202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boron, W.F. Sharpey-Schafer Lecture: Gas channels. Exp. Physiol. 2010, 95, 1107–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G.; Zhou, Y.; Bouyer, P.; Grichtchenko, I.; Boron, W. Transport of Volatile Solutes Through AQP1. J. Physiol. 2002, 542, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisbren, S.J.; Geibel, J.P.; Modlin, I.M.; Boron, W.F. Unusual Permeability Properties of Gastric Gland Cells. Nature 1994, 368, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, S.A.; Gutknecht, J. Solubility of Carbon Dioxide in Lipid Bilayer Membranes and Organic Solvents. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1980, 596, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Föster, R.E.; Gros, G.; Lin, L.; Ono, Y.; Wunder, M. The Effect of 4,4’-diisothiocyanato-stilbene-2,2’-disulfonate on CO2 Permeability of the Red Blood Cell Membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 15815–15820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widomska, J.; Raguz, M.; Subczynski, W.K. Oxygen Permeability of the Lipid Bilayer Membrane Made of Calf Lens. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1768, 2635–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischkoff, S.; Vanderkooi, J. Oxygen diffusion in biological and artificial membranes determined by the fluorochrome pyrene. J. Gen. Physiol. 1975, 65, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subczynski, W.K.; Hyde, J.S.; Kusumi, A. Oxygen Permeability of Phosphatidylcholine-cholesterol Membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 4474–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subczynski, W.K.; Hyde, J.S.; Kusumi, A. Effects of Alkyl Chain Unsaturation and Cholesterol Intercalation on Oxygen Transport in Membranes: A Pulse ESR Spin Labeling Study. Biochemistry 1991, 30, 8578–8590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subczynski, W.; Hopwood, L.; Hyde, J. Is the Mammalian Cell Plasma Membrane a Barrier to Oxygen Transport? J. Gen. Physiol. 1992, 100, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, T.X.; Xu, Y.H.; Anderson, B.D. The Barrier Domain for Solute Permeation Varies with Lipid Bilayer Phase Structure. J. Membr. Biol. 1998, 165, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehlein, N.; Otto, B.; Eilingsfeld, A.; Itel, F.; Meier, W.; Kaldenhoff, R. Gas-tight Triblock-copolymer Membranes Are Converted to CO2 Permeable by Insertion of Plant Aquaporins. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiavaliaris, G.; Itel, F.; Hedfalk, K.; Al-Samir, S.; Meier, W.; Gros, G.; Endeward, V. Low CO2 Permeability of Cholesterol-containing Liposomes Detected by Stopped-flow Fluorescence Spectrosopy. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 1780–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhoul, N.L.; Davis, B.A.; Romero, M.F.; Boron, W.F. Effect of Expressing the Water Channel Aquaporin-1 on the CO2 Permeability of Xenopus Oocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1998, 274, C543–C548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, G.V.T.; Coury, L.; Finn, F.; Zeidel, M. Reconstituted Aquaporin 1 Water Channels Transport CO2 Across Membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 33123–33126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terashima, I.; Ono, K. Effects of HgCl2 on CO2 Dependence of Leaf Photosynthesis: Evidence Indicating Involvement of Aquaporins in CO2 Diffusion Across the Plasma Membrane. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002, 43, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehlein, N.; Lovisolo, C.; Siefritz, F.; Kaldenhoff, R. The Tobacco Aquaporin NtAQP1 Is a Membrane CO2 Pore with Physiological Functions. Nature 2003, 425, 734–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endeward, V.; Cartron, J.P.; Ripoche, P.; Gros, G. RhAG Protein of the Rhesus Complex Is a CO2 Channel in Human Red Cell Membrane. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa-Aziz, R.; Chen, L.M.; Pelletier, M.F.; Qin, X.; Boron, W.F. Relative CO2/NH3 selectivities in AQP1, AQP4, AQP5, AmtB, and RhAG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 5406–5411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geyer, R.R.; Musa-Aziz, R.; Qin, X.; Boron, W.F. Relative CO2/NH3 selectivities of mammalian aquaporins 0–9. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2013, 304, C985–C994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kai, L.; Kaldenhoff, R. A Refined Model of Water and CO2 Membrane Diffusion: Effects and Contribution of Sterols and Proteins. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missner, A.; Pohl, P. 100 Years of the Meyer-Overton Rule: Predicting Membrane Permeability of Gases and Other Small Compounds. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2009, 10, 1405–1414. [Google Scholar]

- Hulikova, A.; Swietach, P. CrossTalk Opposing View: Physiological CO2 Exchange Does Not Normally Depend on Membrane Channels. J. Physiol. 2015, 593, 5029–5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boron, W.F.; Endeward, V.; Gros, G.; Musa-Aziz, R.; Pohl, P. Intrinsic CO2 Permeability of Cell Membranes and Potential Biological Relevance of CO2 Channels. ChemPhysChem 2011, 12, 1017–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endeward, V.; Al-Samir, S.; Itel, F.; Gros, G. How does carbon dioxide permeate cell membranes? A discussion of concepts, results and methods. Front. Physiol. 2014, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bemporad, D.; Luttmann, C.; Essex, J.W. Permeation of Small Molecules Through a Lipid Bilayer: A Computer Simulation Study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 4875–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.T.; Comer, J.; Herndon, C.; Leung, N.; Pavlova, A.; Swift, R.V.; Tung, C.; Rowley, C.N.; Amaro, R.E.; Chipot, C.; et al. Simulation-based Approaches for Determining Membrane Permeability of Small Compounds. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2016, 56, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vos, O.; Venable, R.M.; Van Hecke, T.; Hummer, G.; Pastor, R.W.; Ghysels, A. Membrane Permeability: Characteristic Times and Lengths for Oxygen and a Simulation-Based Test of the Inhomogeneous Solubility-Diffusion Model. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2018, 14, 3811–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, M.; Wang, E.; Zhuang, X.; Klauda, J.B. Simulations of Simple Bovine and Homo Sapiens Outer Cortex Ocular Lens Membrane Models. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2018, 1860, 2134–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Klauda, J.B. Examination of Mixtures Containing Sphingomyelin and Cholesterol by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121, 4833–4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, I.; Klauda, J.B. Molecular Simulations of Mixed Lipid Bilayers with Sphingomyelin, Glycerophospholipids, and Cholesterol. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121, 5197–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonen, E. Cellular Cholesterol Trafficking and Compartmentalization. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subczynski, W.K.; Raguz, M.; Widomska, J.; Mainali, L.; Konovalov, A. Functions of Cholesterol and the Cholesterol Bilayer Domain Specific to the Fiber-Cell Plasma Membrane of the Eye Lens. J. Membr. Biol. 2012, 245, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramstedt, B.; Slotte, J.P. Membrane Properties of Sphingomyelins. FEBS Lett. 2002, 531, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainali, L.; Raguz, M.; O’Brien, W.J.; Subczynski, W.K. Properties of Membranes Derived From the Total Lipids Extracted From the Human Lens Cortex and Nucleus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2013, 1828, 1432–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veath, S.L.; Ivan, V.P.; Gawrisch, K.; Keller, S.L. Liquid Domains in Vesicles Investigated by NMR and Fluorescence Microscopy. Biophys. J. 2004, 86, 2910–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodt, A.J.; Sander, M.L.; Gawrisch, K.; Pastor, R.W.; Lyman, E. The Molecular Structure of the Liquid-Ordered Phase of Lipid Bilayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; London, E. The Effect of Sterol Structure on Membrane Lipid Domains Reveals How Cholesterol Can Induce Lipid Domain Formation. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veath, S.L.; Keller, S.L. Separation of Liquid Phases in Giant Vesciles of Ternary Mixtures of Phospholipids and Cholesterol. Biophys. J. 2003, 85, 3074–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heberle, F.A.; Wu, J.; Goh, S.L.; Petruzielo, R.S.; Feigenson, G.W. Comparison of Three Ternary Lipid Bilayer Mixtures: FRET and ESR Reveal Nanodomains. Biophys. J. 2010, 99, 3309–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.A.; London, E. Functions of Lipid Rafts in Biological Membranes. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 1998, 14, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, K.; Ikonen, E. Functional Rafts in Cell Membranes. Nature 1997, 387, 569–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, K.; Ikonen, E. How Cells Handle Cholesterol. Science 2000, 290, 1721–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, E.; Levental, I.; Mayor, S.; Eggeling, C. The Mystery of Membrane Organization: Composition, Regulation and Roles of Lipid Rafts. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Tieleman, D.P.; Wang, Y. Microsecond Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Lipid Mixing. Langmuir 2014, 30, 11993–12001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Shinoda, W. Cholesterol Effects on Water Permeability Through DPPC and PSM Lipid Bilayers: A Molecular Dynamics Study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 15241–15250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hub, J.S.; Winkler, F.K.; Merrick, M.; de Groot, B.L. Potentials of Mean Force and Permeabilities for Carbon Dioxide, Ammonia, and Water Flux Across a Rhesus Protein Channel and Lipid Membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 13251–13263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennberg, C.L.; van der Spoel, D.; Hub, J.S. Large Influence of Cholesterol on Solute Partitioning into Lipid Membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 5351–5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zocher, F.; van der Spoel, D.; Pohl, P.; Hub, J.S. Local partition coefficients govern solute permeability of cholesterol-containing membranes. Biophys. J. 2013, 105, 2760–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dotson, R.J.; Smith, C.R.; Bueche, K.; Angles, G.; Pias, S.C. Influences of Cholesterol on the Oxygen Permeability of Membranes: Insight From Atomistic Simulations. Biophys. J. 2017, 112, 2336–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kim, T.; Iyer, V.G.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: A Web-based Graphical User Interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKerell, A.D., Jr.; Bashford, D.; Bellott, M.; Dunbrack, R.L., Jr.; Evanseck, J.D.; Field, M.J.; Fischer, S.; Gao, J.; Guo, H.; Ha, S.; et al. All-atom Empirical Potential for Molecular Modeling and Dynamics Studies of Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 3586–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klauda, J.B.; Venable, R.M.; Freites, J.A.; O’Connor, J.W.; Tobias, D.J.; Mondragon-Ramirez, C.; Vorobyov, I.; MacKerell, A.D., Jr.; Pastor, R.W. Update of the CHARMM All-atom Additive Force Field for Lipids: Validation on Six Lipid Types. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 7830–7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.B.; Rogaski, B.; Klauda, J.B. Update of the Cholesterol Force Field Parameters in CHARMM. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venable, R.M.; Sodt, A.J.; Rogaski, B.; Rui, H.; Hatcher, E.; MacKerrell, A.D., Jr.; Pastor, R.W.; Klauda, J.B. CHARMM All-Atom Additive Force Field for Sphingomyelin: Elucidation of Hydrogen Bonding and of Positive Curvature. Biophys. J. 2014, 107, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanommeslaeghe, K.; Hatcher, E.; Acharya, C.; Kundu, S.; Zhong, S.; Shim, J.; Darian, E.; Guvench, O.; Lopes, P.; Vorobyov, I.; et al. CHARMM General Force Field: A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 671–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, J.C.; Braun, R.; Wang, W.; Gumbart, J.; Tajkhorshid, E.; Villa, E.; Chipot, C.; Skeel, R.D.; Kale, L.; Schulten, K. Scalable Molecular Dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1781–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.C.; Hardy, D.J.; Maia, J.D.C.; Stone, J.E.; Ribeiro, J.V.; Bernardi, R.C.; Buch, R.; Fiorin, G.; Hénin, J.; Jiang, W.; et al. Scalable Molecular Dynamics on CPU and GPU Architectures with NAMD. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 044130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, R.B.; Zhu, X.; Shim, J.; Lopes, P.E.M.; Mittal, J.; Feig, M.; MacKerell, A.D. Optimization of the Additive CHARMM All-atom Protein Force Field Targeting Improved Sampling of the Backbone ϕ, ψ and Side-chain χ1 and χ2 Dihedral Angles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 3257–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darden, T.; York, D.; Pedersen, L.G. Particle Mesh Ewald: An N·log(N) Method for Ewald Sums in Large Systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 10089–10092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyna, G.J.; Tobias, D.J.; Klein, M.L. Constant Pressure Molecular Dynamics Algorithms. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 101, 4177–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, S.E.; Zhang, Y.; Pastor, R.W.; Brooks, B.R. Constant Pressure Molecular Dynamics Simulation: The Langevin Piston Method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 4613–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryckaert, J.P.; Ciccotti, G.; Berendsen, H.J.C. Numerical Integration of the Cartesian Equations of Motion of a System With Constraints: Molecular Dynamics of N-Alkanes. J. Comp. Phys. 1977, 23, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeer, L.S.; de Groot, B.L.; Réat, V.; Milon, A.; Czaplicki, J. Acyl Chain Order Parameter Profiles in Phosphopholipid Bilayers: Computation From Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Comparison with 2H NMR Experiments. Eur. Biophys. J. 2007, 36, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gapsys, V.; de Groot, B.L.; Briones, R. Computational Analysis of Local Membrane Properties. J. Comp.-Aided Mol. Design 2013, 27, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofsäß, C.; Lindahl, E.; Edholm, O. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Phospholipid Bilayers with Cholestrol. Biophys. J. 2003, 84, 2192–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindbolm, G.; Orädd, G. Lipid Lateral Diffusion and Membrane Heterogeneity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1788, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molugu, T.R.; Lee, S.; Brown, M.F. Concepts and Methods of Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy Applied to Biomembranes. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 12087–12131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein, A. Water Movement Through Lipid Bilayers, Pores, and Plasma Membranes; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, J.M.; Katz, Y. Interpretation of Nonelectrolyte Partition Coefficients Between Dimyristoyl Lecithin and Water. J. Membrane Biol. 1974, 17, 121–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipot, C.; Comer, J. Subdiffusion in Membrane Permeation of Small Molecules. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsov, Z.; Gonzalez-Ramirez, E.J.; Goni, F.M.; Tristram-Nagle, S.; Nagle, J.F. Phase Behavior of Palmitoyl and Egg Sphingomyelin. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2018, 213, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodt, A.J.; Pastor, R.W.; Lyman, E. Hexagonal Substructure and Hydrogen Bonding in Liquid-Ordered Phases Containing Palmitoyl Sphingomyelin. Biophys. J. 2015, 109, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinzeller, A. Chapter 1 Charles Ernest Overton’s Concept of a Cell Membrane. In Membrane Permeability; Current Topics in Membranes; Deamer, D.W., Kleinzeller, A., Fambrough, D.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; Volume 48, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahinthichaichan, P.; Gennis, R.; Tajkhorshid, E. All the O2 Consumed by Thermus thermophilus Cytochrome ba3 Is Delivered to the Active Site Through a Long, Open Hydrophobic Tunnel with Entrances Within the Lipid Bilayer. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 1265–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Shaikh, S.A.; Tajkhorshid, E. Exploring Transmembrane Diffusion Pathways with Molecular Dynamics. Physiology 2010, 25, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Cohen, J.; Boron, W.F.; Schulten, K.; Tajkhorshid, E. Exploring Gas Permeability of Cellular Membranes and Membrane Channels with Molecular Dynamics. J. Struct. Biol. 2007, 157, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Lipid Ratio | Lipid Numbers | System Size (Atoms) |

|---|---|---|

| POPC:PSM:CHL | ||

| 100:0:0 | 294/0/0 | 77,406 |

| 50:0:50 | 186/0/186 | 79,413 |

| 35:0:65 | 154/0/286 | 85,207 |

| 0:100:0 | 0/362/0 | 80,823 |

| 0:50:50 | 0/210/210 | 84,098 |

| 50:50:0 | 162/162/0 | 83,253 |

| 33:33:33 | 124/124/124 | 81,324 |

| 25:25:50 | 100/100/200 | 82,599 |

| POPC:DPPC:CHL | ||

| 50:50:0 | 154/154/0 | 78,708 |

| 0:50:50 | 0/196/196 | 79,346 |

| 33:33:33 | 118/118/118 | 78,997 |

| <[gasbulk]> | <Areaxy> | pd,mem | Dapp | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ns) | (mM) | (Å2) | (Å) | (cm/s) | (10−6 cm2/s) | |

| POPC:PSM:CHL | O2 | |||||

| 100:0:0 | 175 | 54 | 9486 | 44 | 12 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.1 |

| 50:0:50 | 250 | 86 | 8022 | 46 | 15.9 ± 1.8 | 3.4 ± 0.4 |

| 35:0:65 | 250 | 77 | 8967 | 44 | 10.9 ± 1.0 | 2.8 ± 0.3 |

| 0:100:0 | 400 | 76 | 9245 | 48 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.0 |

| 0:50:50 | 400 | 115 | 8346 | 50 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.3 |

| POPC:PSM:CHL | CO2 | |||||

| 100:0:0 | 175 | 125 | 9545 | 44 | 16.6 ± 0.8 | 3.5 ± 0.2 |

| 50:0:50 | 250 | 182 | 8017 | 46 | 9.8 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.1 |

| 35:0:65 | 250 | 173 | 8958 | 44 | 6.3 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 0.3 |

| 0:100:0 | 400 | 165 | 9154 | 48 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.0 |

| 0:50:50 | 400 | 223 | 8342 | 50 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.3 |

| 50:50:0 | 250 | 117 | 9473 | 46 | 8.4 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.0 |

| 33:33:33 | 250 | 178 | 8162 | 50 | 6.5 ± 1.8 | 2.8 ± 0.8 |

| 25:25:50 | 250 | 185 | 8206 | 50 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.4 |

| POPC:DPPC:CHL | CO2 | |||||

| 50:50:0 | 250 | 122 | 9572 | 44 | 14.3 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.0 |

| 33:33:33 | 250 | 198 | 7891 | 48 | 7.1 ± 1.1 | 3.3 ± 0.1 |

| 0:50:50 | 400 | 241 | 7828 | 50 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mahinthichaichan, P.; Raeisi Najafi, A.; Moss, F.J.; Vahedi-Faridi, A.; Boron, W.F.; Tajkhorshid, E. Impact of Lipid Composition on Membrane Partitioning and Permeability of Gas Molecules. Membranes 2026, 16, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010033

Mahinthichaichan P, Raeisi Najafi A, Moss FJ, Vahedi-Faridi A, Boron WF, Tajkhorshid E. Impact of Lipid Composition on Membrane Partitioning and Permeability of Gas Molecules. Membranes. 2026; 16(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahinthichaichan, Paween, Ahmad Raeisi Najafi, Fraser J. Moss, Ardeschir Vahedi-Faridi, Walter F. Boron, and Emad Tajkhorshid. 2026. "Impact of Lipid Composition on Membrane Partitioning and Permeability of Gas Molecules" Membranes 16, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010033

APA StyleMahinthichaichan, P., Raeisi Najafi, A., Moss, F. J., Vahedi-Faridi, A., Boron, W. F., & Tajkhorshid, E. (2026). Impact of Lipid Composition on Membrane Partitioning and Permeability of Gas Molecules. Membranes, 16(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010033