Biological Breakthroughs and Drug Discovery Revolution via Cryo-Electron Microscopy of Membrane Proteins

Abstract

1. Introduction: The Membrane Protein Drug Discovery Challenge

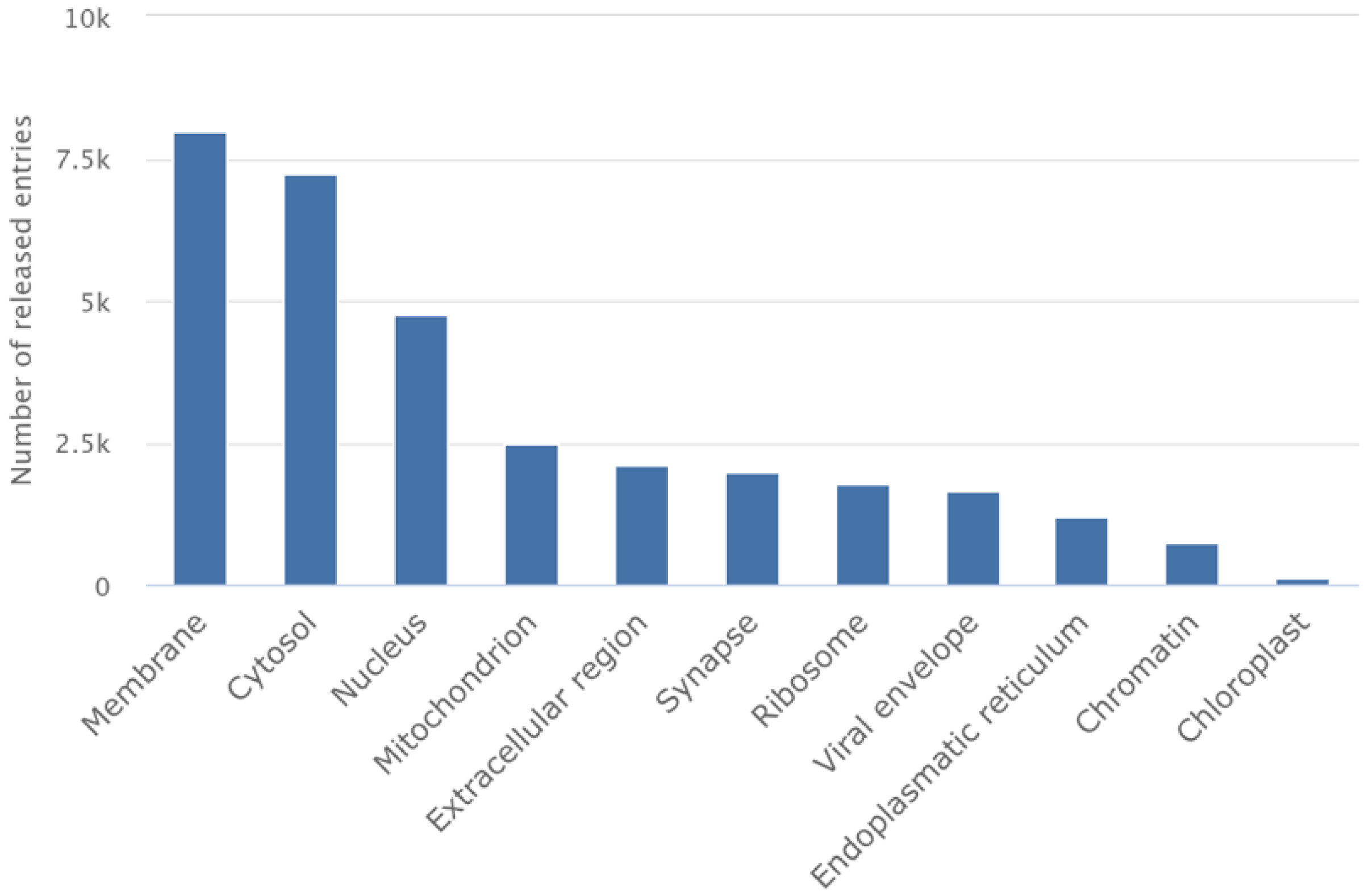

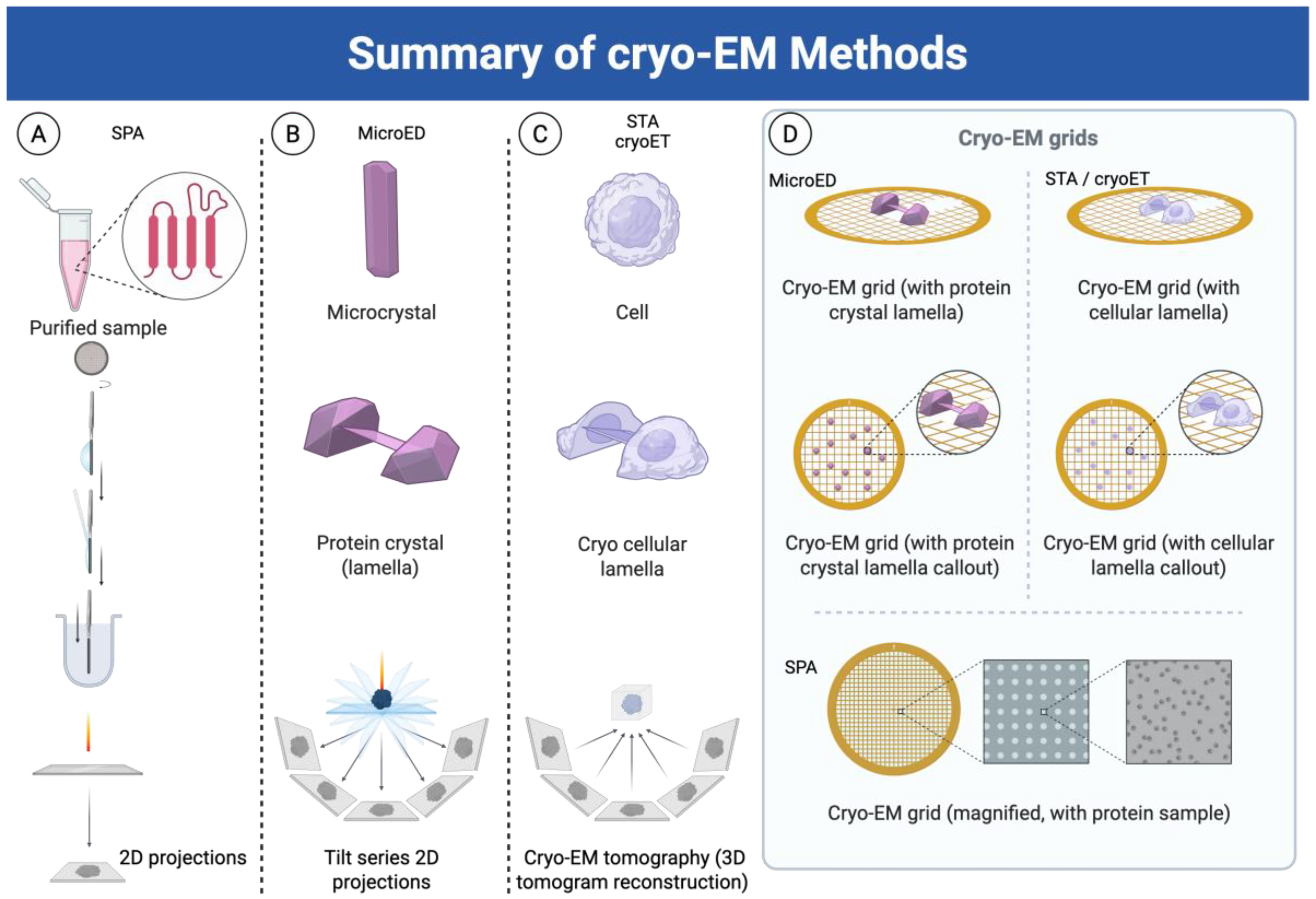

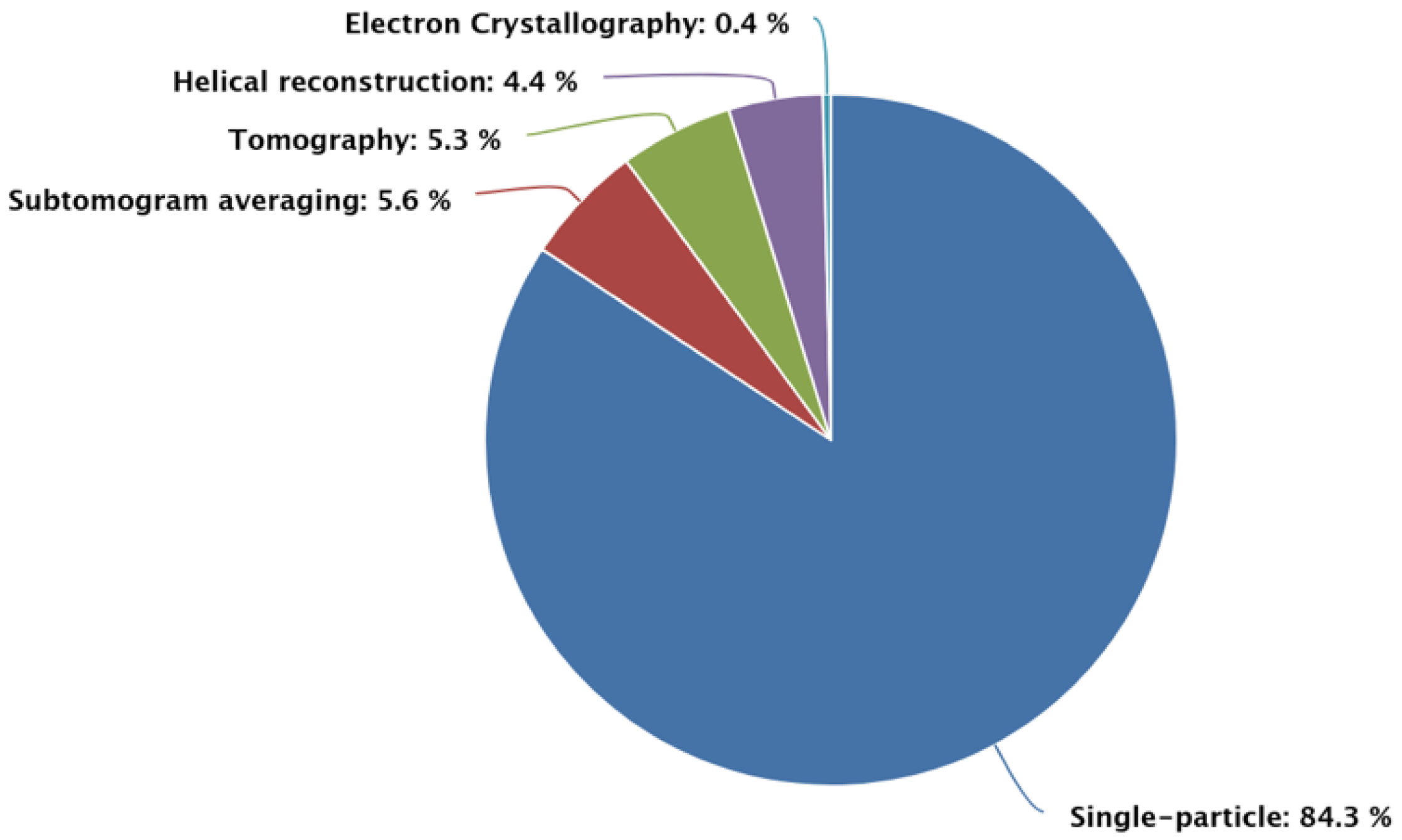

2. Technical Foundations of Cryo-EM for Membrane Studies

2.1. Single Particle Analysis (SPA)

2.2. Subtomogram Averaging (STA)

2.3. Micro-Electron Diffraction (microED)

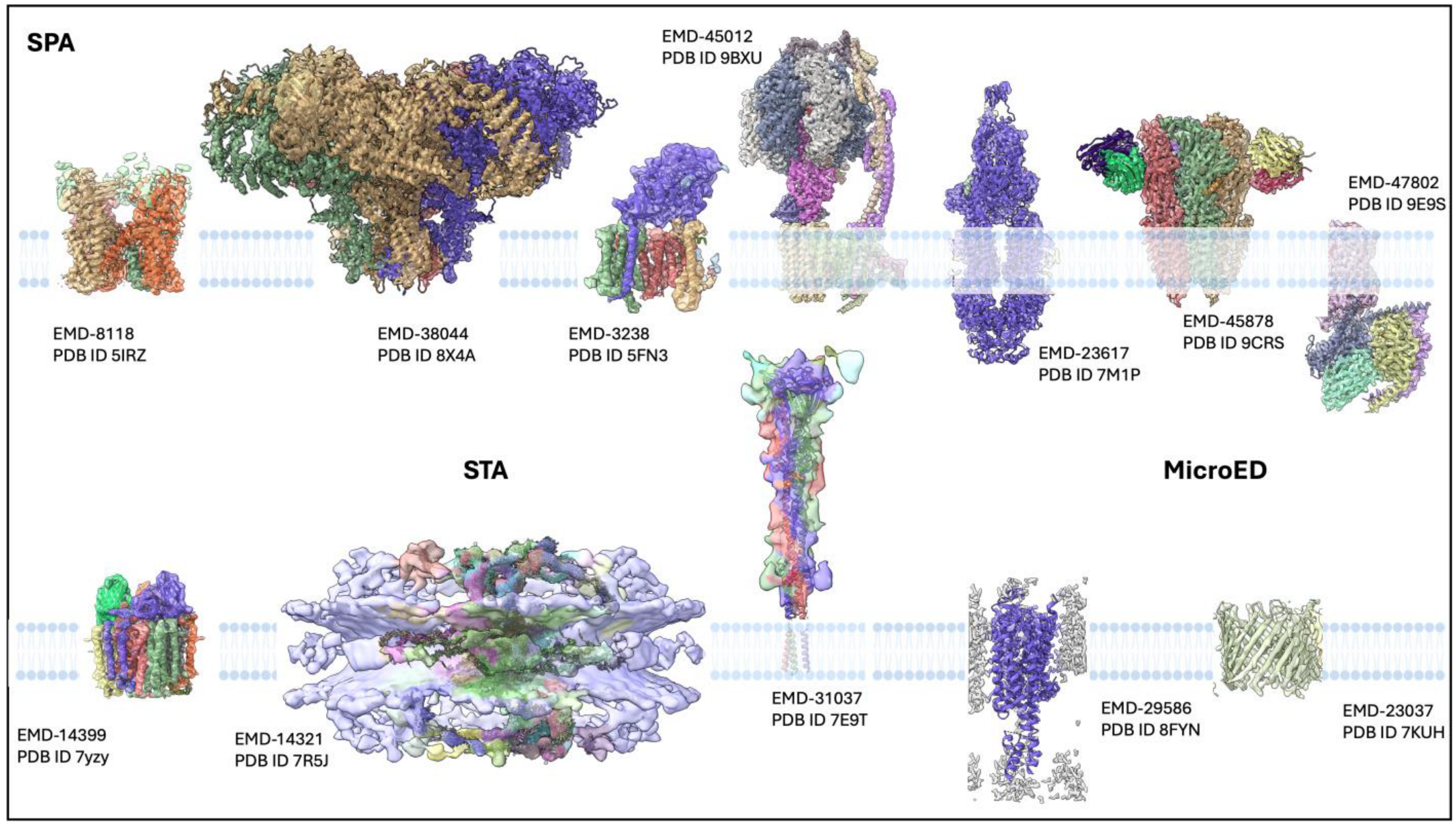

3. Revolutionary Impact on Membrane Protein Structure Determination

3.1. Breakthrough Structures

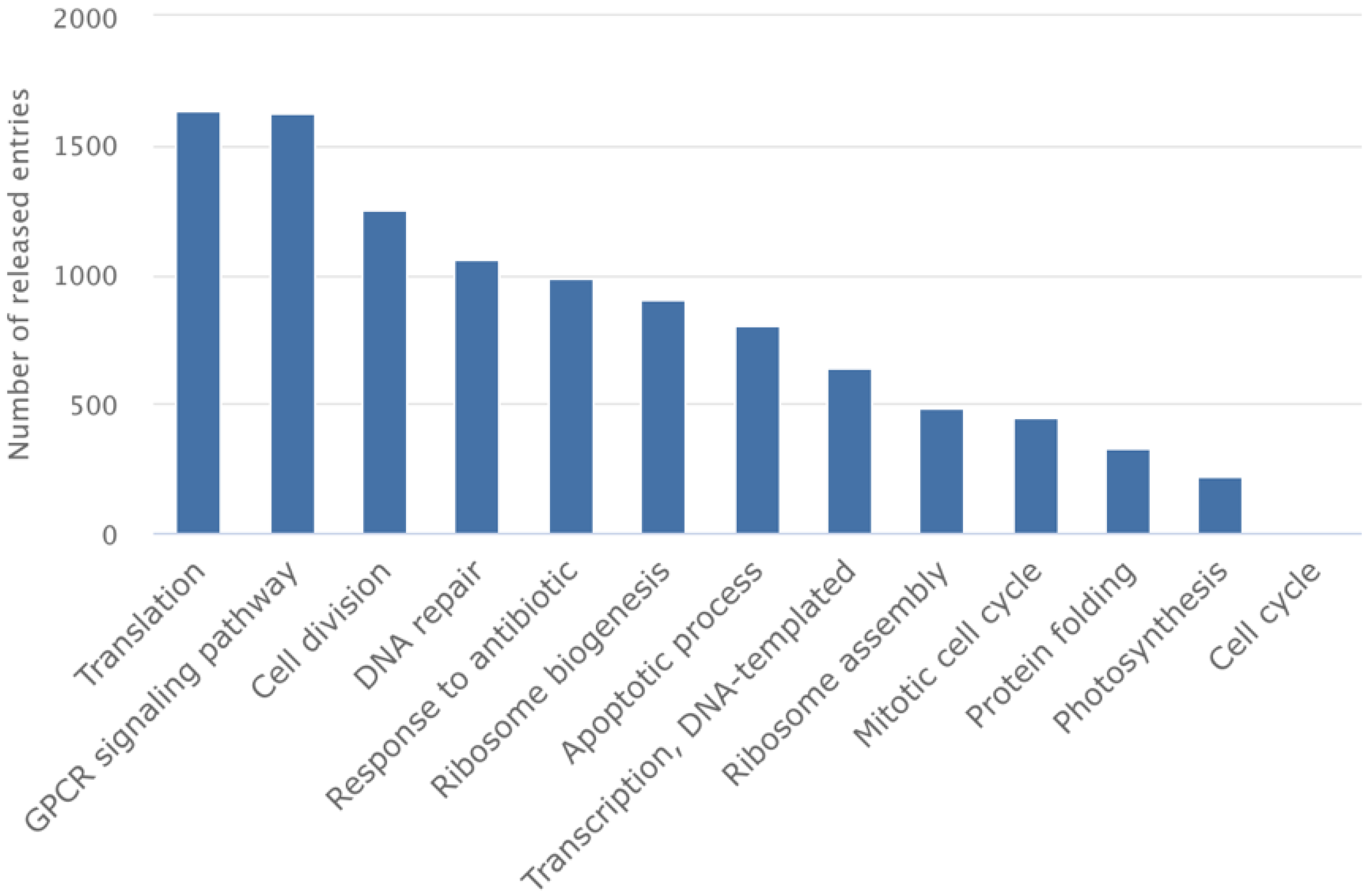

3.2. G Protein-Coupled Receptors: The Holy Grail of Drug Targets

3.3. In Situ Visualization of Membranes and TM Proteins in Action

3.4. MicroED as a Powerful Method to Understand TM-Proteins

4. Current Challenges and Technical Limitations

5. Conclusions and Future Outlook

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Watson, H. Biological Membranes. Essays Biochem. 2015, 59, 43–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorter, E.; Grendel, F. On Bimolecular Layers of Lipoids on the Chromocytes of the Blood. J. Exp. Med. 1925, 41, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overington, J.P.; Al-Lazikani, B.; Hopkins, A.L. How Many Drug Targets Are There? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 993–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L. The Rapid Developments of Membrane Protein Structure Biology over the Last Two Decades. BMC Biol. 2023, 21, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch, J.; Cheruvara, H.; Gamage, N.; Harrison, P.J.; Lithgo, R.; Quigley, A. Changes in Membrane Protein Structural Biology. Biology 2020, 9, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühlbrandt, W. Forty Years in cryoEM of Membrane Proteins. Microscopy 2022, 71, i30–i50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühlbrandt, W. The Resolution Revolution. Science 2014, 343, 1443–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühlbrandt, W. Cryo-EM Enters a New Era. eLife 2014, 3, e03678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, J.-P.; Chari, A.; Ciferri, C.; Liu, W.; Rémigy, H.-W.; Stark, H.; Wiesmann, C. Cryo-EM in Drug Discovery: Achievements, Limitations and Prospects. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 471–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.-F.; Yuan, C.; Du, Y.-M.; Sun, K.-L.; Zhang, X.-K.; Vogel, H.; Jia, X.-D.; Gao, Y.-Z.; Zhang, Q.-F.; Wang, D.-P.; et al. Applications and Prospects of Cryo-EM in Drug Discovery. Mil. Med. Res. 2023, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doerr, A. Single-Particle Cryo-Electron Microscopy. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januliene, D.; Moeller, A. Single-Particle Cryo-EM of Membrane Proteins. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2302, 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Grigorieff, N.; Penczek, P.A.; Walz, T. A Primer to Single-Particle Cryo-Electron Microscopy. Cell 2015, 161, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurgan, K.W.; Chen, B.; Brown, K.A.; Cobra, P.F.; Ye, X.; Ge, Y.; Gellman, S.H. Stable Picodisc Assemblies from Saposin Proteins and Branched Detergents. Biochemistry 2021, 60, 1108–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisov, I.G.; Sligar, S.G. Nanodiscs for Structural and Functional Studies of Membrane Proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016, 23, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, P.S.; Rasmussen, S.G.F.; Rana, R.R.; Gotfryd, K.; Chandra, R.; Goren, M.A.; Kruse, A.C.; Nurva, S.; Loland, C.J.; Pierre, Y.; et al. Maltose-Neopentyl Glycol (MNG) Amphiphiles for Solubilization, Stabilization and Crystallization of Membrane Proteins. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 1003–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feingold, K.R. Introduction to Lipids and Lipoproteins. In Endotext; Feingold, K.R., Ahmed, S.F., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M.R., Boyce, A., Chrousos, G., Corpas, E., de Herder, W.W., Dhatariya, K., Dungan, K., et al., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, M.L.; Young, J.W.; Zhao, Z.; Fabre, L.; Jun, D.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Dhupar, H.S.; Wason, I.; Mills, A.T.; et al. The Peptidisc, a Simple Method for Stabilizing Membrane Proteins in Detergent-Free Solution. eLife 2018, 7, e34085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiotis, G.; Notti, R.Q.; Bao, H.; Walz, T. Nanodiscs Remain Indispensable for Cryo-EM Studies of Membrane Proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2025, 92, 103042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punjani, A.; Rubinstein, J.L.; Fleet, D.J.; Brubaker, M.A. cryoSPARC: Algorithms for Rapid Unsupervised Cryo-EM Structure Determination. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakane, T.; Kimanius, D.; Lindahl, E.; Scheres, S.H. Characterisation of Molecular Motions in Cryo-EM Single-Particle Data by Multi-Body Refinement in RELION. eLife 2018, 7, e36861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheres, S.H.W. RELION: Implementation of a Bayesian Approach to Cryo-EM Structure Determination. J. Struct. Biol. 2012, 180, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, T.; Rohou, A.; Grigorieff, N. cisTEM, User-Friendly Software for Single-Particle Image Processing. eLife 2018, 7, e35383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Briggs, J.A.G. Cryo-Electron Tomography and Subtomogram Averaging. Methods Enzym. 2016, 579, 329–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.F.; Walker, M.; Siebert, C.A.; Muench, S.P.; Ranson, N.A. An Introduction to Sample Preparation and Imaging by Cryo-Electron Microscopy for Structural Biology. Methods 2016, 100, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaita, M.; Watters, S.C.; Loerch, S. Recent Advances and Current Trends in Cryo-Electron Microscopy. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2022, 77, 102484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstein, F.; Danev, R.; Pilhofer, M. Improved Applicability and Robustness of Fast Cryo-Electron Tomography Data Acquisition. J. Struct. Biol. 2019, 208, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyle, E.; Hutchings, J.; Zanetti, G. Strategies for Picking Membrane-Associated Particles within Subtomogram Averaging Workflows. Faraday Discuss 2022, 240, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, F.R.; Watanabe, R.; Schampers, R.; Singh, D.; Persoon, H.; Schaffer, M.; Fruhstorfer, P.; Plitzko, J.; Villa, E. Preparing Samples from Whole Cells Using Focused-Ion-Beam Milling for Cryo-Electron Tomography. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 2041–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, N.; Chen, S.-Y.; Lamberz, C.; Bruckner, M.; Dienemann, C.; Burg, T.P. Cryo-iCLEM: Cryo Correlative Light and Electron Microscopy with Immersion Objectives. J. Struct. Biol. 2025, 217, 108179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danev, R.; Buijsse, B.; Khoshouei, M.; Plitzko, J.M.; Baumeister, W. Volta Potential Phase Plate for In-Focus Phase Contrast Transmission Electron Microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 15635–15640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, O.; Axelrod, J.J.; Campbell, S.L.; Turnbaugh, C.; Glaeser, R.M.; Müller, H. Laser Phase Plate for Transmission Electron Microscopy. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 1016–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Bell, J.M.; Shi, X.; Sun, S.Y.; Wang, Z.; Ludtke, S.J. A Complete Data Processing Workflow for Cryo-ET and Subtomogram Averaging. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, B.M.; Davis, J.H. Learning Structural Heterogeneity from Cryo-Electron Sub-Tomograms with tomoDRGN. Nat. Methods 2024, 21, 1525–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nannenga, B.L.; Gonen, T. The Cryo-EM Method Microcrystal Electron Diffraction (MicroED). Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynowycz, M.W.; Shiriaeva, A.; Clabbers, M.T.B.; Nicolas, W.J.; Weaver, S.J.; Hattne, J.; Gonen, T. A Robust Approach for MicroED Sample Preparation of Lipidic Cubic Phase Embedded Membrane Protein Crystals. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynowycz, M.W.; Gonen, T. Studying Membrane Protein Structures by MicroED. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2302, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattne, J.; Reyes, F.E.; Nannenga, B.L.; Shi, D.; de la Cruz, M.J.; Leslie, A.G.W.; Gonen, T. MicroED Data Collection and Processing. Acta Crystallogr. A Found. Adv. 2015, 71, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Cao, E.; Julius, D.; Cheng, Y. Structure of the TRPV1 Ion Channel Determined by Electron Cryo-Microscopy. Nature 2013, 504, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, G.; Peng, W.; Shen, H.; Lei, J.; Yan, N. Structure of the Nav1.4-Β1 Complex from Electric Eel. Cell 2017, 170, 470–482.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Yan, Z.; Li, Z.; Yan, C.; Lu, S.; Dong, M.; Yan, N. Structure of the Voltage-Gated Calcium Channel Cav1.1 Complex. Science 2015, 350, aad2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Yan, C.; Yang, G.; Lu, P.; Ma, D.; Sun, L.; Zhou, R.; Scheres, S.H.W.; Shi, Y. An Atomic Structure of Human γ-Secretase. Nature 2015, 525, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parey, K.; Brandt, U.; Xie, H.; Mills, D.J.; Siegmund, K.; Vonck, J.; Kühlbrandt, W.; Zickermann, V. Cryo-EM Structure of Respiratory Complex I at Work. eLife 2018, 7, e39213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laube, E.; Schiller, J.; Zickermann, V.; Vonck, J. Using Cryo-EM to Understand the Assembly Pathway of Respiratory Complex I. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 2024, 80, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusch, N.; Dreimann, M.; Senkler, J.; Rugen, N.; Kühlbrandt, W.; Braun, H.-P. Cryo-EM Structure of the Respiratory I + III2 Supercomplex from Arabidopsis Thaliana at 2 Å Resolution. Nat. Plants 2023, 9, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agip, A.-N.A.; Chung, I.; Sanchez-Martinez, A.; Whitworth, A.J.; Hirst, J. Cryo-EM Structures of Mitochondrial Respiratory Complex I from Drosophila Melanogaster. eLife 2023, 12, e84424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parey, K.; Haapanen, O.; Sharma, V.; Köfeler, H.; Züllig, T.; Prinz, S.; Siegmund, K.; Wittig, I.; Mills, D.J.; Vonck, J.; et al. High-Resolution Cryo-EM Structures of Respiratory Complex I: Mechanism, Assembly, and Disease. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax9484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühlbrandt, W.; Carreira, L.A.M.; Yildiz, Ö. Cryo-EM of Mitochondrial Complex I and ATP Synthase. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2025, 54, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Zhu, H.; Clark, S.; Gouaux, E. Cryo-EM Structures Reveal Native GABAA Receptor Assemblies and Pharmacology. Nature 2023, 622, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, J.A.; Kim, J.; Liu, B.; Popescu, G.K.; Gouaux, E.; Jalali-Yazdi, F. Cryo-EM Snapshots of NMDA Receptor Activation Illuminate Sequential Rearrangements. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadx4647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, D.; Jormakka, M.; Juge, N.; Kishikawa, J.; Kato, T.; Sugita, Y.; Noda, T.; Uemura, T.; Shiimura, Y.; Miyaji, T.; et al. Neurotransmitter Recognition by Human Vesicular Monoamine Transporter 2. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, C.N.; Yang, F.; Ita, S.; Xu, Y.; Akunuri, R.; Trampari, S.; Neumann, C.M.T.; Desdorf, L.M.; Schiøtt, B.; Salvino, J.M.; et al. Cryo-EM Structure of the Dopamine Transporter with a Novel Atypical Non-Competitive Inhibitor Bound to the Orthosteric Site. J. Neurochem. 2024, 168, 2043–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dai, F.; Chen, N.; Zhou, D.; Lee, C.-H.; Song, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Structural Insights into VAChT Neurotransmitter Recognition and Inhibition. Cell Res. 2024, 34, 665–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, S.; McMahon, H.T. Mechanisms of Membrane Fusion: Disparate Players and Common Principles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, J.B. SNARE Complexes Prepare for Membrane Fusion. Trends Neurosci. 2005, 28, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, F.C.; Dean, T.T.; Minari, K.; Basso, L.G.M.; Vance, T.D.R.; Serrão, V.H.B. A Frame-by-Frame Glance at Membrane Fusion Mechanisms: From Viral Infections to Fertilization. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, T.; Cavellini, L.; Kühlbrandt, W.; Cohen, M.M. A Mitofusin-Dependent Docking Ring Complex Triggers Mitochondrial Fusion in Vitro. eLife 2016, 5, e14618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, D.C.; Johnson, E.; Lewinson, O. ABC Transporters: The Power to Change. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, G.A.; Shukla, S.; Rao, P.; Borgnia, M.J.; Bartesaghi, A.; Merk, A.; Mobin, A.; Esser, L.; Earl, L.A.; Gottesman, M.M.; et al. Cryo-EM Analysis of the Conformational Landscape of Human P-Glycoprotein (ABCB1) During Its Catalytic Cycle. Mol. Pharmacol. 2016, 90, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shvarev, D.; Januliene, D.; Moeller, A. Frozen Motion: How Cryo-EM Changes the Way We Look at ABC Transporters. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2022, 47, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, T.; Lu, X.; Lan, X.; Chen, Z.; Lu, S. G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs): Advances in Structures, Mechanisms and Drug Discovery. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danev, R.; Belousoff, M.; Liang, Y.-L.; Zhang, X.; Eisenstein, F.; Wootten, D.; Sexton, P.M. Routine Sub-2.5 Å Cryo-EM Structure Determination of GPCRs. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gui, M.; Wang, Z.-F.; Gorgulla, C.; Yu, J.J.; Wu, H.; Sun, Z.J.; Klenk, C.; Merklinger, L.; Morstein, L.; et al. Cryo-EM Structure of an Activated GPCR–G Protein Complex in Lipid Nanodiscs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2021, 28, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusach, A.; García-Nafría, J.; Tate, C.G. New Insights into GPCR Coupling and Dimerisation from Cryo-EM Structures. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2023, 80, 102574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papasergi-Scott, M.M.; Pérez-Hernández, G.; Batebi, H.; Gao, Y.; Eskici, G.; Seven, A.B.; Panova, O.; Hilger, D.; Casiraghi, M.; He, F.; et al. Time-Resolved Cryo-EM of G-Protein Activation by a GPCR. Nature 2024, 629, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Johnson, R.M.; Drulyte, I.; Yu, L.; Kotecha, A.; Danev, R.; Wootten, D.; Sexton, P.M.; Belousoff, M.J. Evolving Cryo-EM Structural Approaches for GPCR Drug Discovery. Structure 2021, 29, 963–974.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.-L.; Khoshouei, M.; Radjainia, M.; Zhang, Y.; Glukhova, A.; Tarrasch, J.; Thal, D.M.; Furness, S.G.B.; Christopoulos, G.; Coudrat, T.; et al. Phase-Plate Cryo-EM Structure of a Class B GPCR-G Protein Complex. Nature 2017, 546, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K.M.; Strauss, M.; Daum, B.; Kief, J.H.; Osiewacz, H.D.; Rycovska, A.; Zickermann, V.; Kühlbrandt, W. Macromolecular Organization of ATP Synthase and Complex I in Whole Mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 14121–14126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W. A Practical Look at Cryo-Electron Tomography Image Processing: Key Considerations for New Biological Discoveries. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2025, 93, 103116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Premaraj, N.; Heeren, R.M.A.; Ravelli, R.B.G.; Knoops, K. Advancing Cryo-EM and Cryo-ET through Innovation in Sample Carriers: A Perspective. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 11959–11967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Chai, P.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, K. High-Resolution in Situ Structures of Mammalian Respiratory Supercomplexes. Nature 2024, 631, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Gu, J.; Guo, R.; Huang, Y.; Yang, M. Structure of Mammalian Respiratory Supercomplex I1III2IV1. Cell 2016, 167, 1598–1609.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letts, J.A.; Fiedorczuk, K.; Degliesposti, G.; Skehel, M.; Sazanov, L.A. Structures of Respiratory Supercomplex I+III2 Reveal Functional and Conformational Crosstalk. Mol. Cell 2019, 75, 1131–1146.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, R.; Graça, A.; Forsman, J.; Aydin, A.O.; Hall, M.; Gaetcke, J.; Chernev, P.; Wendler, P.; Dobbek, H.; Messinger, J.; et al. Cryo–Electron Microscopy Reveals Hydrogen Positions and Water Networks in Photosystem II. Science 2024, 384, 1349–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ma, J.; Li, X.; Sui, S.-F. In Situ Cryo-ET Structure of Phycobilisome–Photosystem II Supercomplex from Red Alga. eLife 2021, 10, e69635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitan, O.; Chen, M.; Kuang, X.; Cheong, K.Y.; Jiang, J.; Banal, M.; Nambiar, N.; Gorbunov, M.Y.; Ludtke, S.J.; Falkowski, P.G.; et al. Structural and Functional Analyses of Photosystem II in the Marine Diatom Phaeodactylum Tricornutum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 17316–17322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrão, V.H.B.; Cook, J.D.; Lee, J.E. Snapshot of an Influenza Virus Glycoprotein Fusion Intermediate. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Fusco, M.L.; Hessell, A.J.; Oswald, W.B.; Burton, D.R.; Saphire, E.O. Structure of the Ebola Virus Glycoprotein Bound to an Antibody from a Human Survivor. Nature 2008, 454, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, R.M.; Vaney, M.-C.; Tortorici, M.A.; Kurdi, R.A.; Barba-Spaeth, G.; Krey, T.; Rey, F.A. Functional and Evolutionary Insight from the Crystal Structure of Rubella Virus Protein E1. Nature 2013, 493, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez, M.G.; O’Rourke, S.M.; Dzimianski, J.V.; Gagnon, D.; Penunuri, G.; Serrão, V.H.B.; Corbett-Detig, R.B.; Kauvar, L.M.; DuBois, R.M. Structures of Respiratory Syncytial Virus G Bound to Broadly Reactive Antibodies Provide Insights into Vaccine Design. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanning, S.; Aguilar-Hernández, N.; Serrão, V.H.B.; López, T.; O’Rourke, S.M.; Lentz, A.; Ricemeyer, L.; Espinosa, R.; López, S.; Arias, C.F.; et al. Discovery of Three Novel Neutralizing Antibody Epitopes on the Human Astrovirus Capsid Spike and Mechanistic Insights into Virus Neutralization. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e0161924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzimianski, J.V.; Nagashima, K.A.; Cruz, J.M.; Sautto, G.A.; O’Rourke, S.M.; Serrão, V.H.B.; Ross, T.M.; Mousa, J.J.; DuBois, R.M. Assessing the Structural Boundaries of Broadly Reactive Antibody Interactions with Diverse H3 Influenza Hemagglutinin Proteins. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e0045325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munro, J.B.; Gorman, J.; Ma, X.; Zhou, Z.; Arthos, J.; Burton, D.R.; Koff, W.C.; Courter, J.R.; Smith, A.B.; Kwong, P.D.; et al. Conformational Dynamics of Single HIV-1 Envelope Trimers on the Surface of Native Virions. Science 2014, 346, 759–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vénien-Bryan, C.; Fernandes, C.A.H. Overview of Membrane Protein Sample Preparation for Single-Particle Cryo-Electron Microscopy Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, L.; Chlanda, P. Cryo-Electron Tomography of Viral Infection—From Applications to Biosafety. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2023, 61, 101338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, M.; Acharya, P. Cryo-Electron Microscopy in the Study of Virus Entry and Infection. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1429180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wachsmuth-Melm, M.; Peterl, S.; O’Riain, A.; Makroczyová, J.; Fischer, K.; Krischuns, T.; Vale-Costa, S.; Amorim, M.J.; Chlanda, P. Visualizing Influenza A Virus Assembly by in Situ Cryo-Electron Tomography. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, L.; Sun, D.; Ning, J.; Liu, J.; Kotecha, A.; Olek, M.; Frosio, T.; Fu, X.; Himes, B.A.; Kleinpeter, A.B.; et al. CryoET Structures of Immature HIV Gag Reveal Six-Helix Bundle. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akıl, C.; Xu, J.; Shen, J.; Zhang, P. Unveiling the Structural Spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 Fusion by in Situ Cryo-ET. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Z.; Oton, J.; Qu, K.; Cortese, M.; Zila, V.; McKeane, L.; Nakane, T.; Zivanov, J.; Neufeldt, C.J.; Cerikan, B.; et al. Structures and Distributions of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Proteins on Intact Virions. Nature 2020, 588, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrapp, D.; Wang, N.; Corbett, K.S.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Abiona, O.; Graham, B.S.; McLellan, J.S. Cryo-EM Structure of the 2019-nCoV Spike in the Prefusion Conformation. Science 2020, 367, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yao, H.; Wu, N.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, C.; Li, S.; Kong, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, M.; et al. In Situ Architecture and Membrane Fusion of SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2213332120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, M.; Hurt, E. The Nuclear Pore Complex: Understanding Its Function through Structural Insight. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-W.; Chen, S.; Tocheva, E.I.; Treuner-Lange, A.; Löbach, S.; Søgaard-Andersen, L.; Jensen, G.J. Correlated Cryogenic Photoactivated Localization Microscopy and Cryo-Electron Tomography. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 737–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.X.; Simjanoska, M.; Fitzpatrick, A.W.P. Four-Dimensional microED of Conformational Dynamics in Protein Microcrystals on the Femto-to-Microsecond Timescales. J. Struct. Biol. 2023, 215, 107941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Gonen, T. MicroED Structure of the NaK Ion Channel Reveals a Na+ Partition Process into the Selectivity Filter. Commun. Biol. 2018, 1, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, G.; Nannenga, B.L. MicroED Sample PreparationSample Preparation and Data Collection For Protein CrystalsCrystals. In cryoEM: Methods and Protocols; Gonen, T., Nannenga, B.L., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 287–297. ISBN 978-1-0716-0966-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Li, H.; Clarke, O.B. High-Resolution Ab Initio Reconstruction Enables Cryo-EM Structure Determination of Small Particles. bioRxiv 2025. bioRxiv:2025.09.08.674935. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, J. Time-Resolved Cryo-Electron Microscopy: Recent Progress. J. Struct. Biol. 2017, 200, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamid, J.; Pfeffer, S.; Schaffer, M.; Villa, E.; Danev, R.; Kuhn Cuellar, L.; Förster, F.; Hyman, A.A.; Plitzko, J.M.; Baumeister, W. Visualizing the Molecular Sociology at the HeLa Cell Nuclear Periphery. Science 2016, 351, 969–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Nafría, J.; Tate, C.G. Cryo-EM Structures of GPCRs Coupled to Gs, Gi and Go. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2019, 488, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Sample Type | Key Strengths | Limitations | Typical Resolution | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Particle Analysis (SPA) | Purified, isolated macromolecular complexes | Highest achievable resolution; no need for crystals; flexible conformational analysis | Requires many particles and biochemical purity; not ideal for heterogeneous cellular environments | ~2–3 Å | Membrane proteins, complexes, dynamic assemblies in vitro |

| Subtomogram Averaging (STA) | Repeating structures inside cells or native environments (from tomograms) | Studies proteins in situ; preserves cellular context; tolerates heterogeneity | Lower particle numbers; limited by tomogram SNR; typically, lower resolution than SPA | ~4–8 Å | Viral spikes, ribosomes in cells, large assemblies in native membranes |

| Cryo-Electron Tomography (cryo-ET) | Intact cells, organelles, thick specimens, pleomorphic structures | True 3D snapshots of cells; captures rare, heterogeneous states; no need for averaging | Lower resolution; missing wedge; high dose limits; requires thinning for thick samples | ~3–5 nm | Cellular architecture, organelles, ultrastructure, native-state complexes |

| Micro-electron Diffraction (MicroED) | Nanocrystals of proteins or small molecules | Atomic resolution from crystals too small for X-ray; minimal sample quantity | Requires crystallization; data collection geometry is specialized | ~1–2 Å | Small proteins, peptides, small molecules, membrane protein nanocrystals |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balasco Serrão, V.H. Biological Breakthroughs and Drug Discovery Revolution via Cryo-Electron Microscopy of Membrane Proteins. Membranes 2025, 15, 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120368

Balasco Serrão VH. Biological Breakthroughs and Drug Discovery Revolution via Cryo-Electron Microscopy of Membrane Proteins. Membranes. 2025; 15(12):368. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120368

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalasco Serrão, Vitor Hugo. 2025. "Biological Breakthroughs and Drug Discovery Revolution via Cryo-Electron Microscopy of Membrane Proteins" Membranes 15, no. 12: 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120368

APA StyleBalasco Serrão, V. H. (2025). Biological Breakthroughs and Drug Discovery Revolution via Cryo-Electron Microscopy of Membrane Proteins. Membranes, 15(12), 368. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120368