Study on Low Thermal-Conductivity of PVDF@SiAG/PET Membranes for Direct Contact Membrane Distillation Application

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

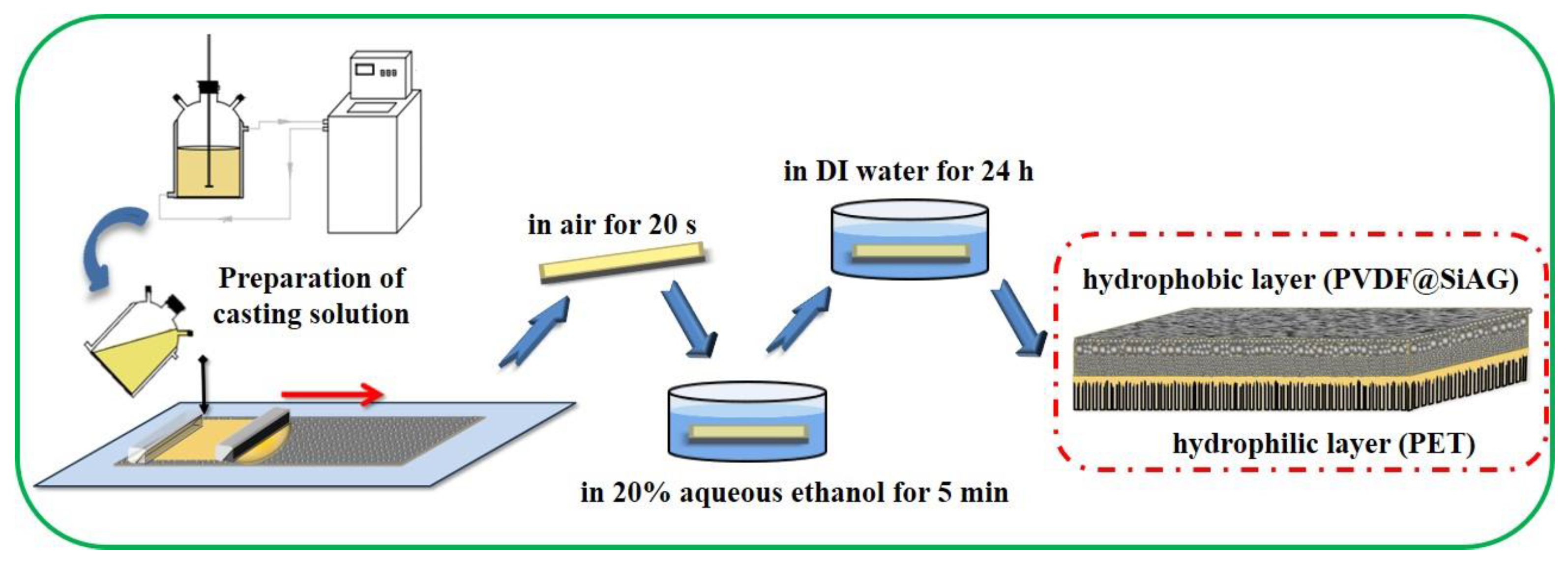

2.2. Preparation of the Hydrophobic/Hydrophilic Membranes

2.3. Structural Characterization

2.4. Thermal Conductivity Test

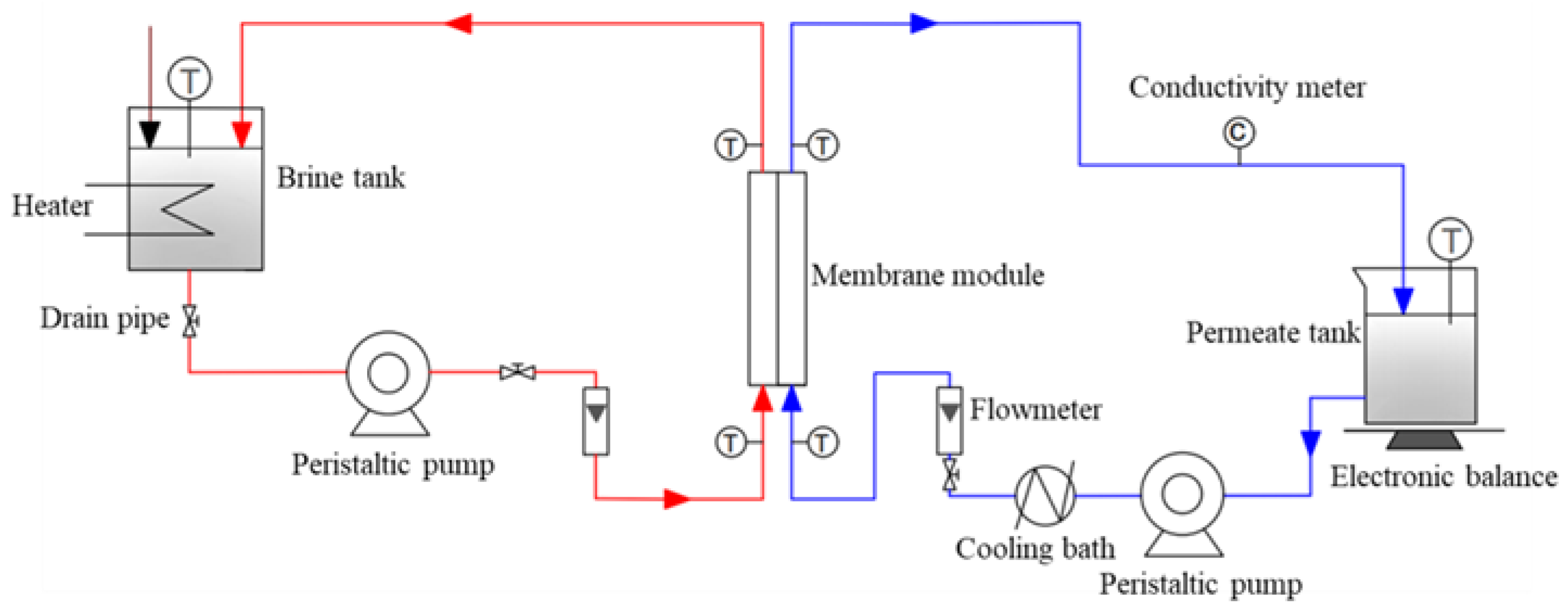

2.5. Batch Test of the DCMD

3. Results and Discussion

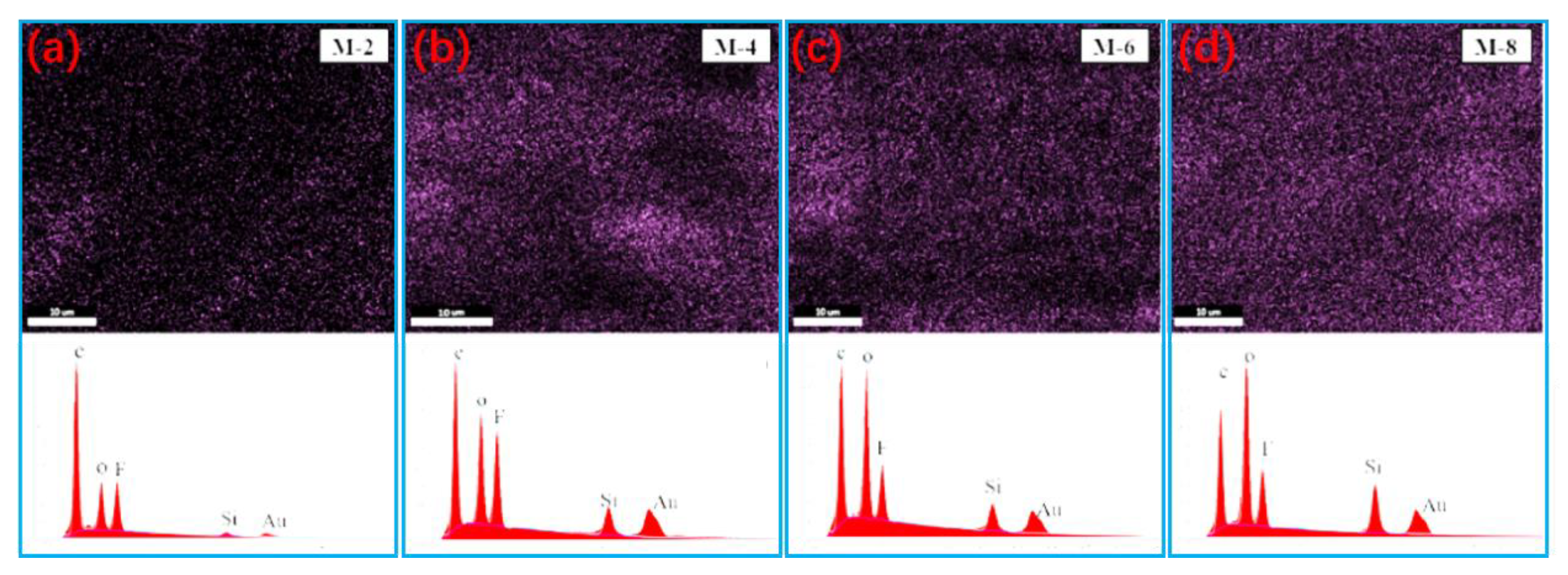

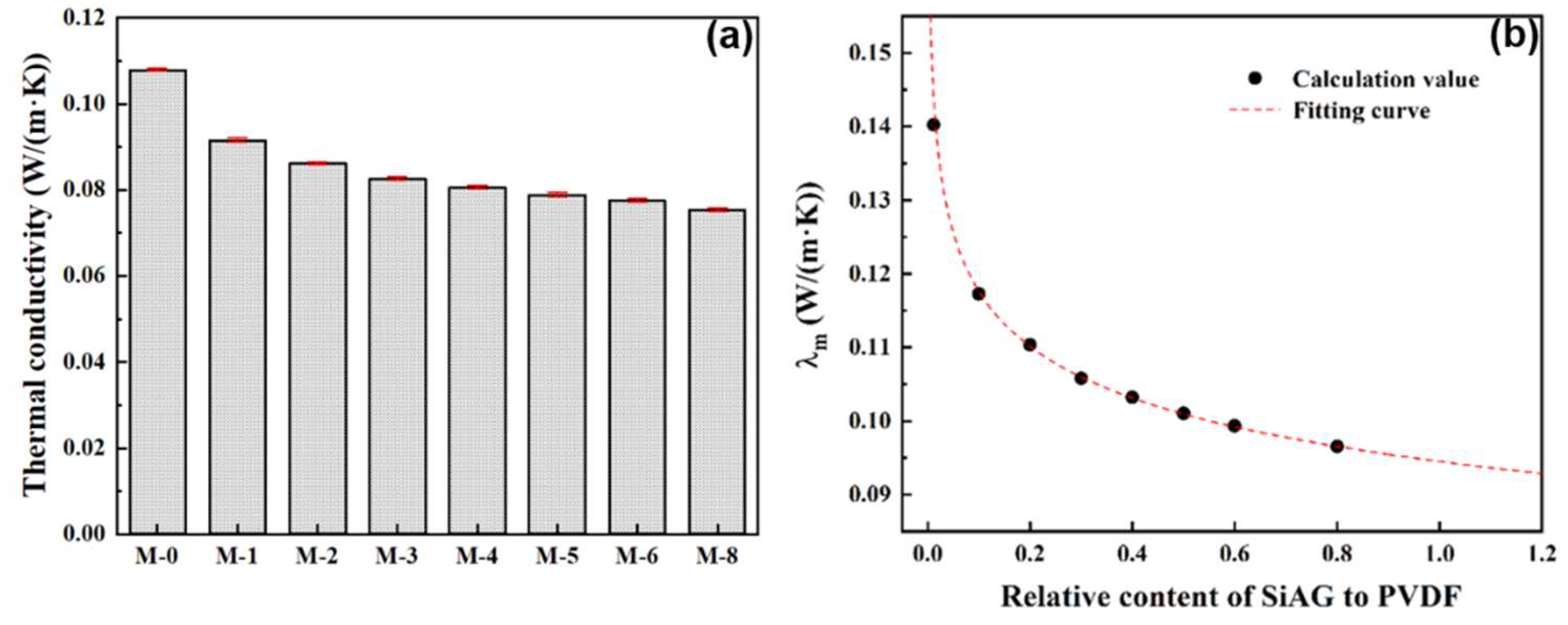

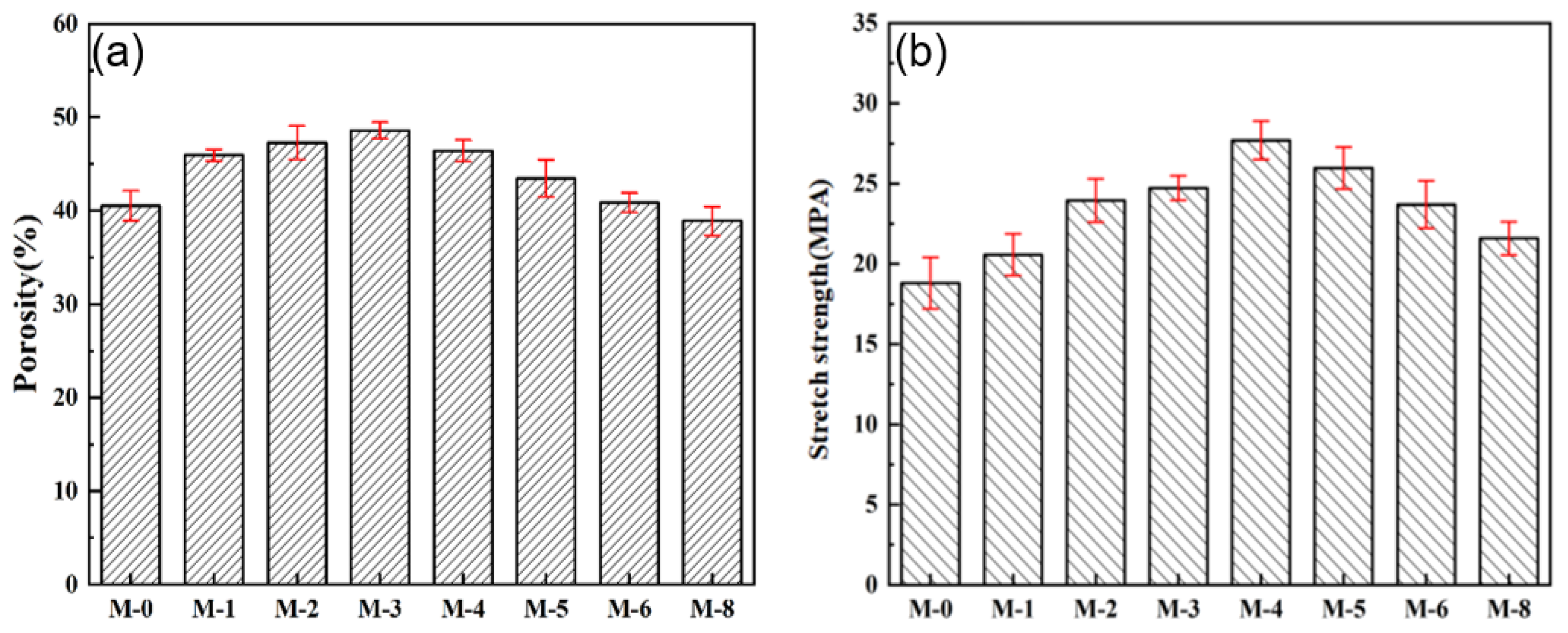

3.1. Characterization of the PVDF@SiAG/PET Membranes

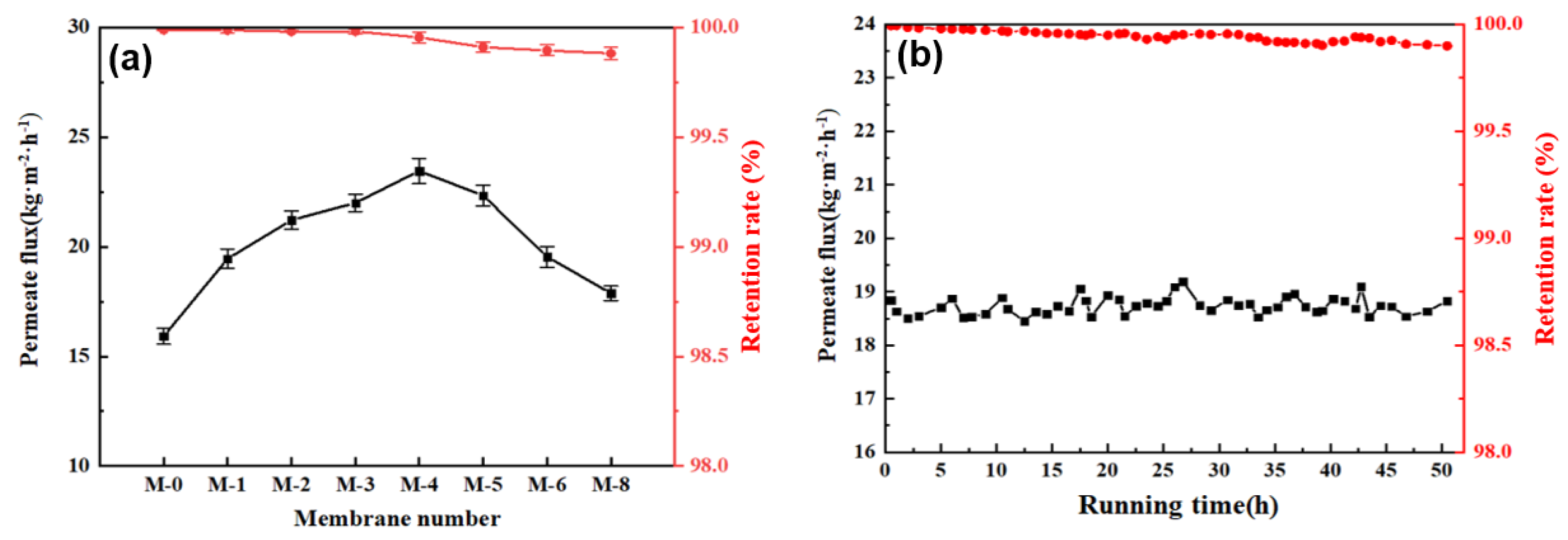

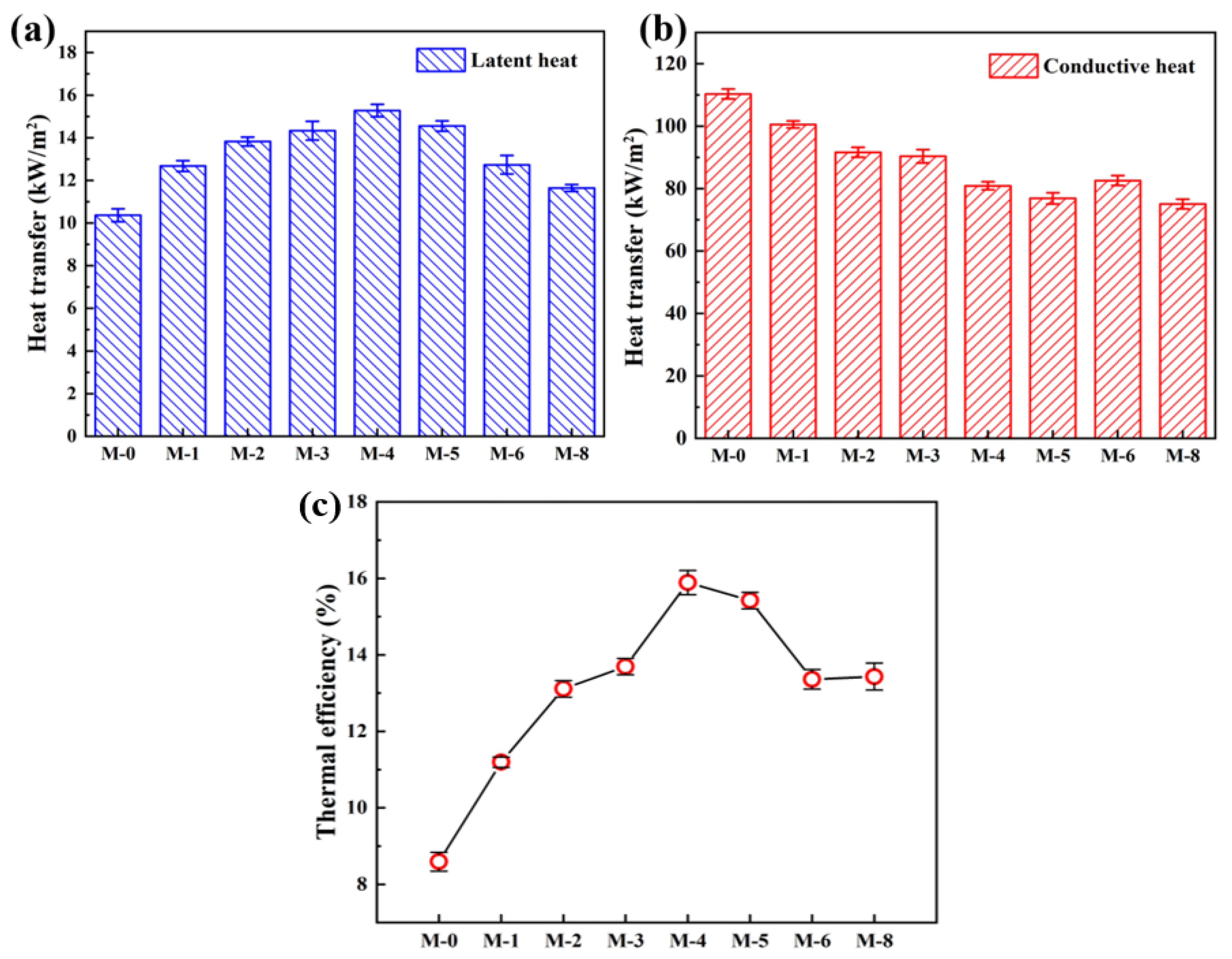

3.2. Effect of PVDF@SiAG/PET Membranes on DCMD

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grasso, G.; Galiano, F.; Yoo, M.J.; Mancuso, R.; Park, H.B.; Gabriele, B.; Figoli, A.; Drioli, E. Development of graphene-PVDF composite membranes for membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 604, 118017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A.A.; Kattan Readi, O.M. An industrial perspective on membrane distillation processes. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 93, 2047–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M.M.A.; Dumée, L.F. Membrane distillation for sustainable wastewater treatment. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 47, 102670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wu, B. Research Progress in Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulations of Membrane Distillation Processes: A Review. Membranes 2021, 11, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonyadi, S.; Chung, T.S. Flux enhancement in membrane distillation by fabrication of dual layer hydrophilic–hydrophobic hollow fiber membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2007, 306, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhudhiri, A.; Darwish, N.; Hilal, N. Membrane distillation: A comprehensive review. Desalination 2012, 287, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, X.-M.; Gilron, J.; Kong, D.-f.; Yin, Y.; Oren, Y.; Linder, C.; He, T. CF4 plasma-modified superhydrophobic PVDF membranes for direct contact membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 456, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, J. A polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)–silica aerogel (SiAG) insulating membrane for improvement of thermal efficiency during membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 597, 117632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Peng, Y.; Dong, Y.; Fan, H.; Chen, P.; Qiu, L.; Jiang, Q. Effects of thermal efficiency in DCMD and the preparation of membranes with low thermal conductivity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 317, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wu, C.; Lu, X.; Ng, D.; Truong, Y.B.; Zhang, J.; Xie, Z. Theoretical guidance for fabricating higher flux hydrophobic/hydrophilic dual-layer membranes for direct contact membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 596, 117608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wang, J.; Yu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, Y. Preparation of PVDF-CTFE hydrophobic membrane by non-solvent induced phase inversion: Relation between polymorphism and phase inversion. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 550, 480–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashoor, B.B.; Mansour, S.; Giwa, A.; Dufour, V.; Hasan, S.W. Principles and applications of direct contact membrane distillation (DCMD): A comprehensive review. Desalination 2016, 398, 222–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, X.; Wang, X.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, X.; Li, L. Preparation of PU modified PVDF antifouling membrane and its hydrophilic performance. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 520, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, H.; Feldman, E.; Guzman, P.; Cole, J.; Wei, Q.; Chu, B.; Alkhudhiri, A.; Alrasheed, R.; Hsiao, B.S. Electrospun polystyrene nanofibrous membranes for direct contact membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 515, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Wang, J.; Sun, X.; Ji, Z.; Luan, Z. Preparation and properties of PVDF composite hollow fiber membranes for desalination through direct contact membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 405–406, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.J.; Shin, I.H. Graft copolymerization of GMA and EDMA on PVDF to hydrophilic surface modification by electron beam irradiation. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2020, 52, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, A.; Bouazizi, N.; Giraud, S.; El Achari, A.; Campagne, C.; Thoumire, O.; El Moznine, R.; Cherkaoui, O.; Vieillard, J.; Azzouz, A. Polyester-supported Chitosan-Poly(vinylidene fluoride)-Inorganic-Oxide-Nanoparticles Composites with Improved Flame Retardancy and Thermal Stability. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2019, 38, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-Z.; Su, Q.-W. Performance manipulations of a composite membrane of low thermal conductivity for seawater desalination. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018, 192, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-E.; Sun, W.-G.; Kong, Y.-F.; Wu, Q.; Sun, L.; Yu, J.; Xu, Z.-L. Hydrophilic Modification of PVDF Microfiltration Membrane with Poly (Ethylene Glycol) Dimethacrylate through Surface Polymerization. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Eng. 2017, 57, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yang, T.; Guo, J. Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2. Green Process. Synth. 2021, 10, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, N.; Leo, C.P. Fouling prevention in the membrane distillation of phenolic-rich solution using superhydrophobic PVDF membrane incorporated with TiO2 nanoparticles. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016, 167, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makanjuola, O.; Anis, S.F.; Hashaikeh, R. Enhancing DCMD vapor flux of PVDF-HFP membrane with hydrophilic silica fibers. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 263, 118361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliero, M.; Bottino, A.; Comite, A.; Costa, C. Novel hydrophobic PVDF membranes prepared by nonsolvent induced phase separation for membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 596, 117575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindra Babu, B.; Rastogi, N.K.; Raghavarao, K.S.M.S. Concentration and temperature polarization effects during osmotic membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 322, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kong, Y.; Shen, X. Polyvinylidene fluoride aerogel with high thermal stability and low thermal conductivity. Mater. Lett. 2019, 259, 126890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Tan, Y.; Meng, F.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.-X. PVDF/MAF-4 composite membrane for high flux and scaling-resistant membrane distillation. Desalination 2022, 540, 116013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cheng, B.; Ju, J.; Kang, W.; Liu, Y. Development of a novel multi-scale structured superhydrophobic nanofiber membrane with enhanced thermal efficiency and high flux for membrane distillation. Desalination 2021, 501, 114834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Woo, Y.C.; Park, K.H.; Phuntsho, S.; Tijing, L.D.; Yao, M.; Shim, W.-G.; Shon, H.K. Polyvinylidene fluoride phase design by two-dimensional boron nitride enables enhanced performance and stability for seawater desalination. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 598, 117669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Yatim, N.S.; Abd. Karim, K.; Ooi, B.S. Nodular structure and crystallinity of poly(vinylidene fluoride) membranes: Impact on the performance of direct-contact membrane distillation for nutrient isolation. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 46866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wae AbdulKadir, W.A.F.; Ahmad, A.L.; Ooi, B.S. Hydrophobic PVDF-HNT membrane for oxytetracycline removal via DCMD: The influence of fabrication parameters on permeability, selectivity and antifouling properties. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 49, 102960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, Y.C.; Yao, M.; Shim, W.-G.; Kim, Y.; Tijing, L.D.; Jung, B.; Kim, S.-H.; Shon, H.K. Co-axially electrospun superhydrophobic nanofiber membranes with 3D-hierarchically structured surface for desalination by long-term membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 623, 119028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, H.; Shi, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, R.; Qin, X. Preparation of hydrophobic zeolitic imidazolate framework-71 (ZIF-71)/PVDF hollow fiber composite membrane for membrane distillation through dilute solution coating. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 251, 117348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Zhao, L.; Li, N.; Smith, S.J.D.; Wu, D.; Zhang, J.; Ng, D.; Wu, C.; Martinez, M.R.; Batten, M.P.; et al. Aluminum fumarate MOF/PVDF hollow fiber membrane for enhancement of water flux and thermal efficiency in direct contact membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 588, 117204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmaniyan, B.; Mohammadi, T.; Tofighy, M.A. Development of high flux PVDF/modified TNTs membrane with improved properties for desalination by vacuum membrane distillation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | PVDF (wt.%) | SiAG(wt.%) | LiCl (wt.%) | Acetone (wt.%) | DMA (wt.%) | RSiAG * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-0 | 12.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 84.0 | 0.0 |

| M-1 | 12.0 | 1.2 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 82.8 | 0.1 |

| M-2 | 12.0 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 81.6 | 0.2 |

| M-3 | 12.0 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 80.4 | 0.3 |

| M-4 | 6.0 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 87.6 | 0.4 |

| M-5 | 6.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 87.0 | 0.5 |

| M-6 | 6.0 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 86.4 | 0.6 |

| M-8 | 6.0 | 4.8 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 85.2 | 0.8 |

| Membrane Sample | Average Pore Size (nm) | Membrane Flux (L/m2h) | Rejection Rate (%) | Thermal Conductivity (W·m−1·K−1) | Ref. | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVDF/SiAG | 172 | 12.50 | >99.99% | 0.0830 | [8] | 2020 |

| PVDF/MAF-4 | 122 | 27.90 | none | 0.0458 | [26] | 2022 |

| PVDF/TBAHP/PS | 870 | 50.00 | 99.9% | 0.0278 | [27] | 2021 |

| BNNSs/PVDF-co-HFP | 720 | 18.00 | 99.99% | 0.0207 | [28] | 2020 |

| PVDF | 340 | 9.49 | >99% | 0.0521 | [29] | 2018 |

| PVDF/PDMS–SiO2 | 350 | 12.40 | 99.9% | 0.0620 | [9] | 2014 |

| PVDF-HNT | 440 | 7.64 | 100% | 0.0597 | [30] | 2022 |

| PVDF-HFP | 390 | 14.50 | 99.9% | 0.0310 | [31] | 2021 |

| ZIF-71/PVDF | 420 | 27.10 | 99.9% | - | [32] | 2020 |

| AlFu-MOF-PVDF | 297 | 15.64 | >99.9% | 0.3561 | [33] | 2019 |

| PVDF/TNTs | 27 | 92.55 | 99.9% | - | [34] | 2021 |

| PVDF@SiAG/PET | 69 | 23.46 | >99.9% | 0.0754 | this work | 2023 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiang, J.; Wang, S.; Chen, N.; Wen, X.; Tian, G.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, P.; Zhang, J.; Tang, N. Study on Low Thermal-Conductivity of PVDF@SiAG/PET Membranes for Direct Contact Membrane Distillation Application. Membranes 2023, 13, 773. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes13090773

Xiang J, Wang S, Chen N, Wen X, Tian G, Zhang L, Cheng P, Zhang J, Tang N. Study on Low Thermal-Conductivity of PVDF@SiAG/PET Membranes for Direct Contact Membrane Distillation Application. Membranes. 2023; 13(9):773. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes13090773

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiang, Jun, Sitong Wang, Nailin Chen, Xintao Wen, Guiying Tian, Lei Zhang, Penggao Cheng, Jianping Zhang, and Na Tang. 2023. "Study on Low Thermal-Conductivity of PVDF@SiAG/PET Membranes for Direct Contact Membrane Distillation Application" Membranes 13, no. 9: 773. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes13090773

APA StyleXiang, J., Wang, S., Chen, N., Wen, X., Tian, G., Zhang, L., Cheng, P., Zhang, J., & Tang, N. (2023). Study on Low Thermal-Conductivity of PVDF@SiAG/PET Membranes for Direct Contact Membrane Distillation Application. Membranes, 13(9), 773. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes13090773