4.1.1. Gas Permeance Results at Non-Adsorbing Conditions

The experimental study on the gas diffusion through the GO/ceramic composite membranes in concomitance with the survey relative to their pore structural features, initiated by measuring the He permeance (PeHe) at 100 °C and examining various transmembrane pressures (TMP) up to 1.2 bar. The rationale behind the selection of these specific conditions as a starting point of our experimental campaign is that by examining a non-adsorbable gas at elevated temperature, diffusion mechanisms attributed to gas adsorption (surface diffusion) are limited. Hence, the focus stays solely on the Knudsen and Hagen-Poiseuille mechanisms of gas transport through membranes, along with the transition regime (slip flow) between them. In this context, the micropore diffusion process (or molecular sieving process), which describes the motion of gas molecules through pores (micropores) of a dimension close to the kinetic diameter of gases, is excluded at this stage of discussion.

According to the model developed by Weber, the general expression of the gas permeability through a porous medium in the mixed Poiseuille–Knudsen flow regime is described by the following equation [

34]:

where,

the permeability of the porous membrane,

the thickness of the membrane,

the gas flux through the membrane,

the surface of the porous membrane,

the gas concentration difference across the membrane,

the porosity of the membrane,

the tortuosity factor defining the real length

) of the capillaries within the membrane,

the hydraulic diameter of the capillaries,

the gas viscosity,

the mean pressure,

the temperature of the gas,

the molecular weight of the gas,

the gas constant, and

, a dimensionless coefficient accounting for the contribution of Knudsen flow and slip flow, which depends on the Knudsen number (

), where λ (

m) is the mean free path of the gas molecule. The graphical representation of

is a curve that presents a minimum for large Knudsen numbers (

and converges asymptotically to a linear form of the type

, with

A corresponding to the mixed contribution of Knudsen and Slip flow and

B corresponding to the Poiseuille flow.

According to the kinetic theory of gases, the mean free path (λ) of He at 100 °C and pressures up to 550 mbar (the mean gas pressure is considered here, calculated as the average of gas pressures at both sides of the membrane) can vary from λ = 3.4 μm (at 50 mbar) down to λ = 310 nm at a mean pressure of 550 mbar.

Furthermore, when the mean free path of gas molecules is much larger than the pore dimension (, i.e., for large Knudsen number), the second term in Equation (1) becomes zero and the coefficient takes the value of 1. Under these conditions, Knudsen diffusion takes place (permeation evolves solely via collisions of the gas molecules with the pore walls) and the permeance through the membrane is independent of the transmembrane (TMP) pressure (Equation (1)), whereas for larger pore dimensions and at the same conditions of temperature and pressure, the transition to Poiseuille flow commences via the slip flow mechanism, which comes first into play (for 0.1 λ < < 100 λ), and the permeance correlates linearly with TMP.

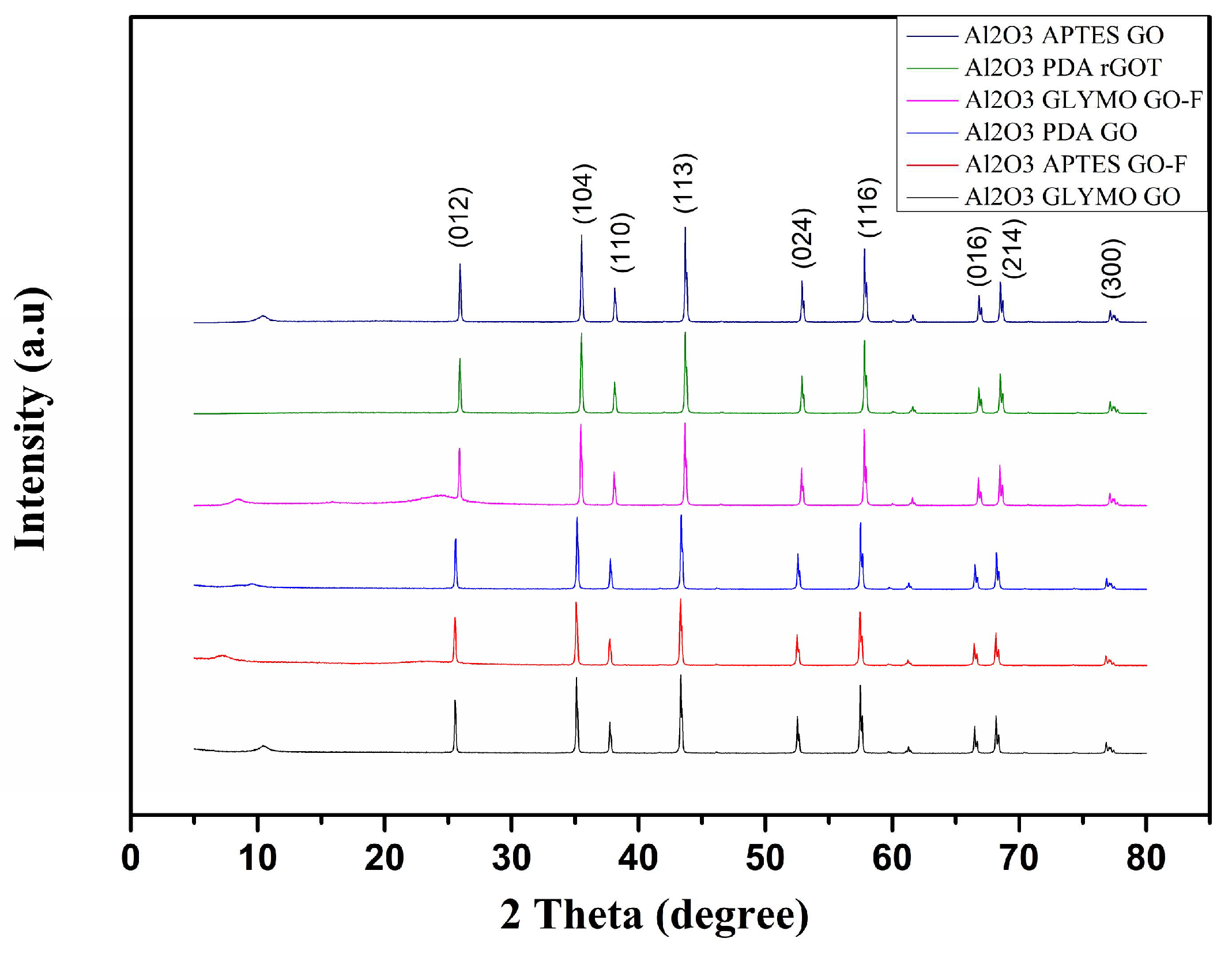

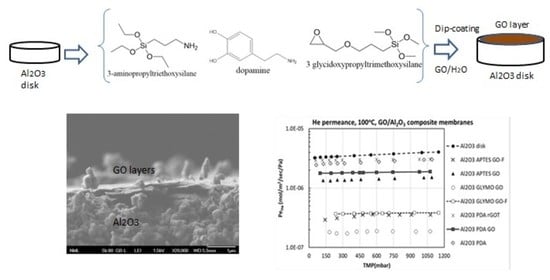

The plots presented in

Figure 8 illustrate the dependence of Pe

He on the TMP at 100 °C for all the developed membranes, including the bare Al

2O

3 and ZrO

2 substrates. It is apparent that the Pe

He of both substrates exhibits slip-to-Poiseuille flow features. Hence, considering that the lower TMPs examined were in the range of 50–100 mbar and that during the measurement the permeate side of the membranes was kept under vacuum conditions, it was possible to estimate that the pore dimension of both substrates is larger than 340 nm. Focusing now on the prepared GO/Al

2O

3 composite membranes (

Figure 8a), it can be concluded that only the ones bearing a multi-layered laminate (prepared by post-filtration), together with the oligo-layered Al

2O

3 GLYMO GO, and Al

2O

3 PDA GO, presented purely Knudsen flow characteristics up to a TMP of 1100 mbar (mean pressure of 550 mbar). Accordingly, their pore dimension is less than 30 nm. Although the setup of the involved permeability rig was not adequate for measuring the permeance at higher TMPs, a missing asset that would allow us to gain a clearer view of how narrow the pores are of the developed membranes. There are two noteworthy issues for discussion here that underline the importance of the obtained results. The first issue is the agreement between the conclusions drawn from the permeance and spectroscopic experiments. Interpreting the results of the Raman analysis in conjunction with XPS, we identified APTES as the less effective molecular bridge for the development of oligo-layered membranes. This is further confirmed by the finding that Al

2O

3 APTES GO exhibits Poiseuille flow within the entire pressure range applied in the experiments (

Figure 8a), which is indicative of a very loose conformation of the oligo-layered stacking along with the existence of large gaps between the neighboring GO nanosheets. The same holds for Al

2O

3 PDA rGOT. It should be mentioned that the expected anatase phase TiO

2 bands were not detected in the Raman spectrum of this membrane. Moreover, the Al

2O

3 PDA membrane that was used as a substrate for the chemical attachment of the rGOT composite exhibited a He permeance of 2.6 × 10

−6 mol/m

2/s/Pa, while the permeance of the derived Al

2O

3 PDA rGOT membrane under the same conditions (TMP of 100 mbar, 373 K) was 2.9 × 10

−6 mol/m

2/s/Pa (see also

Tables S1–S3 in the Supplementary Materials). The increase in permeance as compared to the substrate is an indication that during the thermal treatment at 500 °C (the temperature required to transform amorphous TiO

2 nanoparticles to crystalline anatase phase), the PDA decomposed leading to partial detachment of the deposited rGOT composite. Hence, both the Raman analysis and Pe

HE results indicate the loose structural features and low concentration of the deposited rGOT composite, caused due to decomposition of PDA during the thermal treatment that resulted in the delamination of the formed laminate.

The second issue relates to the extent of permeance reduction in the GO/Al

2O

3 composite membranes as compared to the bare Al

2O

3 disk. First to note is that all the composite membranes endowed with Knudsen flow characteristics exhibit, in parallel, a Pe

He reduction of more than one order of magnitude as compared to the bare substrate. This holds also for the ones developed on the ZrO

2 monolith (

Figure 8b). The second remark is that a high Pe

He value does not suggest that the developed oligo-layered GO laminate is loose and full of gaps. Hence, we turn the focus to the Al

2O

3 PDA GO sample, as an example of a high flux membrane (high Pe

He) with Knudsen flow characteristics, and we aspire to explain its distinguishing features. The key issue is that up to this point, the comparison was based on the permeance (Pe) and not on the permeability factor (P′). In seeking to compare two membranes in terms of their pore structural characteristics, which in the case of the composite GO/ceramic membranes reflect the coherence of the formed GO laminate, the key performance indicator must be the P′. The reason is that P′ is an inherent property of the material, independent of the laminate thickness, whereas the gas permeance (Pe) describes the permeability over the length of the flow path. Hence, the SEM cross-section images of

Figure 5a,c allowed us to estimate the laminate’s thickness on the oligo-layered Al

2O

3 PDA GO membrane at about 38 nm, whereas the thickness of the multi-layered GO laminate on Al

2O

3 GLYMO GO-F was found to be 4.7 μm. Considering that the d-spacing of the GO layers on Al

2O

3 PDA GO is 0.957 nm (from the XRD analysis) and that the thickness of one graphene sheet is 0.335 nm, a total number of twenty-four GO layers could be defined for Al

2O

3 PDA GO, while when conducting the same calculations for Al

2O

3 GLYMO GO-F it was found that a total number of about three thousand GO layers composed the thick laminate deposit. Accordingly, by multiplying the Pe

He values of Al

2O

3 PDA GO and Al

2O

3 GLYMO GO-F membranes at 100 °C and a TMP of 250 mbar (1.8 × 10

−6 and 3.7 × 10

−7 mol·m

−2·s

−1·Pa

−1, respectively, seen in

Table 4) with the defined thicknesses, the respective permeability factors were 6.9 × 10

−14 and 1.7 × 10

−12 (mol·m·m

−2·s

−1·Pa

−1). Conclusively, the oligo-layered GO laminate on Al

2O

3 PDA GO exerts a much higher resistance to the flow of He as compared to the multi-layered deposit on Al

2O

3 GLYMO GO-F, meaning that the GO nanosheets are more uniformly stacked on the ceramic substrate and in intimate proximity each other so that the distances between their edges are minimized. We followed the same procedure for the respective composite membranes developed on the ZrO

2 monolith (

Figure 8b) and the estimated permeability factors were two orders of magnitude lower, indicating that the higher smoothness and possibly the higher concentration of hydroxyl groups on the ZrO

2 surface impart a significantly beneficial effect on the conformation of the GO nanosheets’ assembly. The overall results are appended in

Table 4.

Although both membranes developed on the ZrO2 monolith pose a significant restriction to the passage of He molecules, it is not reasonable to consider this property as an indicator of enhanced gas separation capacity, or as evidence that the formed oligo-layered or multi-layered laminates are composed of perfectly stacked and interlocked GO nanosheets. In addition, in the latter case, the gas transport through the membranes would result in diffusion through micropores, which is an activated process (in many cases mentioned as activated Knudsen diffusion), having the distinctive feature of increasing permeance with the rise of temperature. Actually, none of the membranes developed in this work exhibited such an increasing trend and the dependence of gas permeance on temperature indicates that Knudsen diffusion describes better the mechanism of gas transport through their pore structure. Before going further to the discussion on the permeation properties of other adsorbable gases, where surface and Knudsen contributions to permeance must be elaborated, in the following paragraph we focus on several differences of the PeHe dependence on temperature that were pointed out for some of the GO/ceramic membranes, and we try to relate them with distinct pore structural features.

4.1.2. Dependence of PeHe on Temperature

In

Figure 9, the temperature dependence of Pe

He for all the GO/ceramic composite membranes is presented. To ensure that the observed correlations are not affected by interferences due to Poiseuille flow, which is already evidenced to take place for some of the membranes (

Section 4.1.1), the plotted values of permeance vs. temperature were obtained at the same TMP, e.g., 250 mbar for the Al

2O

3 and 300 mbar for the ZrO

2 deposited samples.

The gas permeance via Knudsen diffusion varies with the square root of the inverse temperature ratio. Although this seems to be contradictory to what is described by the Knudsen term in Equation (1), it can be explained based on the units in which the permeance is expressed. As such, when the unit for permeance is

, the dependence on temperature is exactly as described in Equation (1). However, when the permeance is measured in

, then

must be multiplied by

, where

is the temperature of the membrane. Hence, Equation (1) is transformed to:

Equation (2) shows the variation with the square root of the inverse temperature ratio in the Knudsen regime, especially when the temperatures of the gas and the membrane are the same.

From the plots depicted in

Figure 9, it becomes clear that solely the bare substrates and the oligo-layered GO laminate membranes developed using APTES as a molecular bridge, including the Al

2O

3 PDA rGOT sample, follow this general trend. The correlation of Pe

HE with temperature for the rest of the developed membranes deviates significantly from the Knudsen-defined trend and the deviation becomes higher as the temperature drops from 333 K to 298 K. These features appear in a more perceptive way in

Table 5. Hence, all the multi-layered composite membranes, independently on the substrate and the molecular linker, along with the oligo-layered membranes developed by anchoring the GO laminate with GLYMO and PDA, exhibit a remarkable deviation that can only be attributed to the contribution of surface flow to the overall diffusion mechanism.

This asset unveils that He molecules nesting inside the interlayer galleries of stacked GO nanosheets are readily adsorbed due to the enhanced attractive potential imposed by the proximity of the opposite GO surfaces. The d-spacings defined by XRD are in the range of 8.5 to 12.5 Å. Consequently, the dimension of the GO galleries classifies them as being of microporous size. Diffusion in micropores (micropore diffusion) proceeds via three mechanisms, which include surface diffusion, gas translation diffusion, and configurational diffusion. The dominance of each mechanism depends on the ratio of the pore diameter over the kinetic diameter of the gas molecules, with the configurational regime coming into effect for a ratio of 1, whereas the surface diffusion mechanism dominates when the ratio is higher than around 1.25. In our case, the ratio of the interlayer GO galleries over the kinetic diameter of He is in the range of 2–3. It can be, therefore, concluded that the multi-layered membranes and the oligo-layered ones developed with GLYMO, and PDA hold quite extended regions onto their surface, where the deposited GO laminate is characterized by a perfectly organized assembly of stacked GO nanosheets. The gas molecules can permeate through these regions only through their passage from structural imperfections of the GO nanosheet and further diffusion through the microporous interlayer galleries. Hence, He adsorption into the microporous galleries is readily enhanced, leading to the enhanced contribution of surface diffusion at 25 °C. These are reflected by the abrupt rise of permeance at 25 °C (

Figure 9a,b,

Table 5). Since the largest deviation of Pe

HE at 25 °C was observed for the multi-layered laminate/ceramic composite membranes, ZrO

2 GLYMO GO-F, Al

2O

3 GLYMO GO-F, and Al

2O

3 APTES GO-F it can be stated that these membranes hold GO laminates of enhanced integrity. This means that if the deposited laminate is composed of domains characterized by loose and dense structural assemblies of the GO nanosheets, the dense domains dominate in covering the membrane surface. Further conclusions relative to the gas separation capacity of the membranes and the possibility that the formed laminate totally controls the diffusion of gases are provided in the following section.

4.1.3. Elaboration of Gas Separation Performance in Conjunction with the Knudsen Selectivity Ratio

The permeances of He, CO

2, and CH

4 through the membranes were measured at 298.15 K, 333.15 K, and 373.15 K, and various TMPs up to 1.2 bar. The entire set of results is appended in

Tables S1–S3 of the Supplementary Materials.

In

Figure 10, a comparison between the developed membranes regarding their capacity to separate He (the gas with the smaller kinetic diameter) from CO

2 and CH

4 at 373.15 and 298.15 Κ, and TMPs of 100, 250, and 500 mbar is depicted, along with the respective Knudsen selectivity ratio.

Presenting the results in this fashion facilitates the elaboration of data toward defining the best performing composite membranes, characterized by deposited GO laminates of enhanced integrity. In this respect, the interpretation of the Pe

HE results (

Section 4.1. and

Section 4.1.2) has hitherto concluded that all the developed in this work composite GO/ceramic membranes carry a chemically anchored and continuous GO laminate, which sprawls on their top surface through alternating domains of high- and low-density assemblies of GO. The dense domains are the ones consisting of well-stacked and interlocked GO nanosheets and are endowed with microporous diffusion characteristics that are mostly expressed with the surface diffusion mechanism due to the relatively large size of the inter-layer GO galleries as compared to the kinetic diameter of the examined gases. The looser domains are characterized by the existence of voids between adjacent GO stacks. Nevertheless, for some of the membranes, these voids (empty spaces) are of mesopore size. Therefore, depending on the size of the voids the gas diffusion mechanism through, the low-density domains can span from Knudsen to Poiseuille flow, whereas the surface diffusion mechanism on the pristine graphene part of the GO nanosheet has a minor contribution to the overall flux.

From this perspective, the membranes of enhanced integrity and performance must bear deposited layers whose structure is mostly occupied by dense domains.

The results presented in

Figure 10 show that the post-filtration derived multi-layered laminate membranes, despite their distinguishing Pe

HE dependence on temperature, which was indicative of the dominance of microporous domains within the laminate’s structure (

Section 4.1.2), exhibited Pe

HE/Pe

CO2 selectivity that was lower than the Knudsen separation factor (Knudsen He/CO

2 = 3.32). In addition, the respective oligo-layered laminate membranes presented higher Pe

HE/Pe

CO2 selectivity and, amongst them, Al

2O

3 APTES GO and ZrO

2 GLYMO GO were endowed with a Pe

HE/Pe

CO2 separation performance that overpassed the Knudsen separation factor at the specific conditions of high temperature (373 K) and a low TMP (100 mbar) (

Figure 10).

Endeavoring to explain these contradicting results, it is necessary to define and elaborate reasons that could justify He/CO

2 separation performance as higher than expected by Knudsen diffusion. As such, since He has a smaller kinetic diameter than CO

2; the prevailing cause for a membrane to manifest enhanced He/CO

2 separation performance is to own a purely microporous structure, where gas transport takes place through a molecular sieving process. However, this cannot be the case for our membranes since, subject to the same conditions, their He/CH

4 separation performance should be much higher than what is predicted by Knudsen diffusion (CH

4 has a larger kinetic diameter than CO

2). Nevertheless, both oligo-layered membranes (Al

2O

3 APTES GO, and ZrO

2 GLYMO GO) that presented higher Pe

HE/Pe

CO2 selectivity as compared to the Knudsen selectivity factor, at the same time exhibited Pe

HE/Pe

CH4 selectivity values (

Figure 10a) which were less than the predicted ones by Knudsen diffusion (Knudsen He/CH

4 = 2).

Another frequent reason that renders a GO laminate membrane capable to separate He from CO

2 with a higher performance than the one achieved by Knudsen diffusion, relates to the strong adsorptivity of CO

2 on the oxygenated groups emanating from the GO surface. As such, the intercalated CO

2 molecules are significantly hindered in moving through the interlayer galleries since they must overcome a high energy barrier (being desorbed and then adsorbed again to the next oxygen group—this is similar to diffusion taking place through a hopping mechanism between adsorption sites). In this context, Pe

HE/Pe

CO2 values greater than expected for Knudsen diffusion indicate that GO is attached in a way that most of the oxygenated functional groups are free and exposed towards the core of the pores to interact with CO

2 molecules. This is exactly what happens in the oligo-layered membranes. Apart from the first GO layer, which is anchored on the ceramic surface through chemical bonding between the oxygenated groups and those of the organic linker, the next few layers (25–50,

Table 4) that compose the deposited laminate the oxygenated groups remain intact and are available to interact with CO

2 (there is no linker in-between the succeeding GO layers). In addition, the above results confirm that in the case of the oligo-layered membranes, gas diffusion mostly takes place through the looser domains that dominate the laminate structure. In this context, surface diffusion on the pristine part of the GO nanosheets, an asset that would enhance the CO

2 permeance, has a very low contribution to the overall flux. The reason is that the CO

2 adsorption on the pure graphene surface is moderate because of the weak attractive potential generated between opposite GO surfaces being at a long distance from each other.

Contrariwise, the deficient Pe

HE/Pe

CO2 separation capacity of the multi-layered laminate membranes is not indicative of the existence of bulky empty spaces within the laminate but rather of the higher degree of its integrity. Explanatively, the gas permeation through the multi-layered composite membranes is totally controlled by the extra-deposited and quite thick GO laminate. As confirmed by the results of the Raman analysis, most of the oxygenated functional groups of the GO nanosheets that compose the thick laminate are attacked by the nucleophilic amine groups of EDA. As such, they are not available to interact with the diffusing, through the interlayer galleries, CO

2 molecules. Furthermore, apart from the vanishment of the hindering effect of the GO’s functional groups, CO

2 permeation benefits from the enhancement effect of surface diffusion in micropores. Large amounts of CO

2 are adsorbed on the purely graphitic areas of the GO nanosheets under the attractive potential generated by the proximity of the opposite GO layers. As a result, the contribution of surface diffusion to the overall permeation mechanism is significantly enhanced. In addition, examining the histograms of

Figure 10 from top to down (an increase in TMP) and from left to right (a decrease in temperature), it can be concluded that the Pe

HE/Pe

CO2 separation capacity of the multi-layered laminate membranes decreases with the increase in TMP, as expected because of the higher CO

2 adsorption at elevated TMPs, whereas the trend vs. temperature is not straightforward. To provide a clearer view of this issue, in

Figure 11 we depict the dependence of Pe

HE/Pe

CO2 permselectivity on temperature. In most of the cases, the Pe

HE/Pe

CO2 permselectivity presents a minimum at about 333 K. Considering that the Pe

HE declines continuously as the temperature increases (

Figure 9), the observed minimum signifies that the permeance of CO

2 (Pe

CO2) is significantly augmented at the specific temperature. The fortification of the CO

2 flux up to a certain temperature confirms that the dominant mode of gas diffusion in the multi-layered membranes is surface diffusion into micropores. Explanatively, the mechanism of surface diffusion into micropores is affected by temperature in two ways. Firstly, surface diffusion is an activated mechanism, and the gas diffusivity is amplified, as the temperature increases. On the other hand, the adsorbed amount declines so that the adsorbed concentration gradient over the membrane’s thickness passes through a maximum. The combination of these two effects produces a maximum in permeance with respect to temperature. Although the co-existence of rare low-density domains significantly suppresses the intensity of the CO

2 flux enlargement, the above-described events of minimum Pe

HE/Pe

CO2 selectivity and maximum CO

2 flux with respect to temperature constitute further evidence that the gas permeation in this type of multi-layered laminate composite GO/ceramic membranes takes place mostly through the interlayer galleries of dense laminate domains. Moreover, the fact that the minimum in the Pe

HE/Pe

CO2 separation capacity with respect to temperature appeared for all the membranes and at all the examined TMPs, signifies that the CO

2 adsorption on the plain graphene domains of the GO nanosheets within the deposited laminate is significant even at very low pressures (

Figure 11a–c). Since the CO

2 adsorption at low pressures can be significant solely in micropores, this asset implies that the larger segment of the deposited laminate consists of dense domains of high structural integrity.

Hereafter, with the target to determine the best performance among the three multilayered membranes, we shifted our focus to their Pe

HE/Pe

CH4 separation capacity (

Figure 10a–f). Distinguishing features of CH

4 as compared to CO

2 is its larger kinetic diameter (3.8 Å compared to 3.3 Å for CO

2) and its lower adsorptivity.

In addition, contrary to what happens with CO

2, the CH

4 permeation is not hindered by the presence of oxygenated functional groups, since CH

4 has not any specific affinity for them. As such, CH

4 permeation is mostly contributed by the surface diffusion mechanism taking place on the plain graphene domains. Therefore, the He/CH

4 ratio must be lower than expected by the Knudsen mechanism. This holds for all the membranes developed in this work (both oligo-layered and multi-layered) (

Figure 10), with the exception of one case, this of the multi-layered ZrO

2 GLYMO GO-F membrane, which at low TMP (100 mbar) and high temperature (373 K) had achieved a Pe

HE/Pe

CH4 separation factor of 2.34 (

Figure 10a). Considering that CH

4 is less adsorbable than CO

2, it was expected that the Pe

HE/Pe

CH4 separation capacity would be closer to the Knudsen selectivity as compared to the Pe

HE/Pe

CO2 separation capacity. Indeed, from the data presented in the plots of

Figure 10, it could be calculated that depending on the conditions, the Pe

HE/Pe

CO2 separation capacity of all the multi-layered membranes varied between 68% to 89% of the respective Knudsen separation factor, whereas the Pe

HE/Pe

CH4 separation capacity was in the range of 68% to 117%, with the higher percentages achieved by ZrO

2 GLYMO GO-F. This result points out that the pore structure conformation of ZrO

2 GLYMO GO-F is capable to inhibit the diffusion of the bulkier CH

4 molecules.

4.1.4. Structural Features of the Membranes Elucidated by Gas Permeance in Relation to the Organic Linker and the Pore Structure of the Substrate

Having the target to elucidate whether a molecular linker attached to the internal (pore) surface of the ceramic substrate has the capacity to attract and anchor the GO nanosheets, trapping them inside the pores of the substrate, we have also evaluated the gas permeance properties of a linker-modified substrate, before the attachment of GO. The selected linker was PDA because of its macromolecular structure that significantly hinders possible penetration into the substrate’s pores. Since the two other linkers used in this work (APTES and GLYMO) are small molecules, it was definite that they would be eventually grafted on the pore walls without creating any blocking effect. Hence, the concept behind the selection of PDA was that we wanted to first study an oligo-layered laminate GO/Al2O3 composite membrane, where both the linker and the anchored GO laminate are deposited solely on the external surface, and further use it as a reference case for comparison with the other oligo-layered membranes.

When PDA is attached to the Al

2O

3 surface, the Pe

He drops to a large extent (e.g., at a TMP of 250 mbar, it drops from 3.5 × 10

−6 to 2.6 × 10

−6 mol/m

2/s/Pa) (

Figure 12a). This is an indication that the bulky PDA chains that lie on the external Al

2O

3 surface hinder significantly the permeation of He. In parallel, when dopamine undergoes oxidative polymerization to PDA, the nucleophilic nitrogen atom of its primary amine group reacts with one carbon of the catechol ring forming a five-membered ring with the nitrogen enclosed as a heteroatom. As a result, PDA is rich in secondary amine groups, which have the capacity to bind CO

2 molecules. It can be seen (

Figure 12b) that the Al

2O

3 PDA membrane exhibits a very high He/CO

2 permeance ratio at 373 K and TMP of 100 mbar, which goes beyond the Knudsen selectivity factor. This is because the secondary amine groups strongly adsorb and delay the passage of CO

2. When GO is further attached to the PDA-modified Al

2O

3 membrane, the He permeance declines to 1.8 × 10

−6 mol/m

2/s/Pa and this is evidence that GO nanosheets are transferred from the solution and stabilized on the membrane surface, thus generating lengthier flow paths. What constitutes evidence that the attachment of GO on the membrane surface takes place through chemical interaction between the amine groups and the oxygenated groups of GO is that the Pe

HE/Pe

CO2 separation capacity drops to 2.25 (

Figure 12b). In the absence of amine and oxygenated groups, which are the moieties that strongly bound CO

2, the CO

2 molecules interact solely with the pure graphitic surface. In this context, surface diffusion has a significant contribution to the overall permeance of CO

2. Moreover, the He permeance of the Al

2O

3 PDA GO membrane is much higher than this of the other two membranes prepared with APTES GO and GLYMO GO (

Figure 12c). PDA, due to its bulky conformation, lies solely on the external surface of the Al

2O

3 substrate. On the contrary, the smaller APTES and GLYMO molecules can be chemically attached to the pore walls of the Al

2O

3 substrate. Therefore, there is a higher possibility that in the APTES and GLYMO-modified membranes, small GO nanosheets are intercalated into the macropores of the substrate, narrowing the pore space and causing significant resistance to He flow. What is also indicative of this conformation is that the He/CH

4 permeance ratio of the Al

2O

3 PDA GO membrane is only 1.34 (

Figure 12b) due to CH

4 passing through the pores of the membrane without any significant resistance and the flux being fortified by the surface diffusion mechanism. On the other hand, in membranes Al

2O

3 APTES GO and Al

2O

3 GLYMO GO, the He/CH

4 permeance ratio is higher than 1.8 (

Figure 12d), despite the surface diffusion mechanism and, due to the narrowing of the pores, the passage of the bulkier CH

4 is significantly impeded.