Plasmalogen Replacement Therapy

Abstract

:1. Plasmalogens

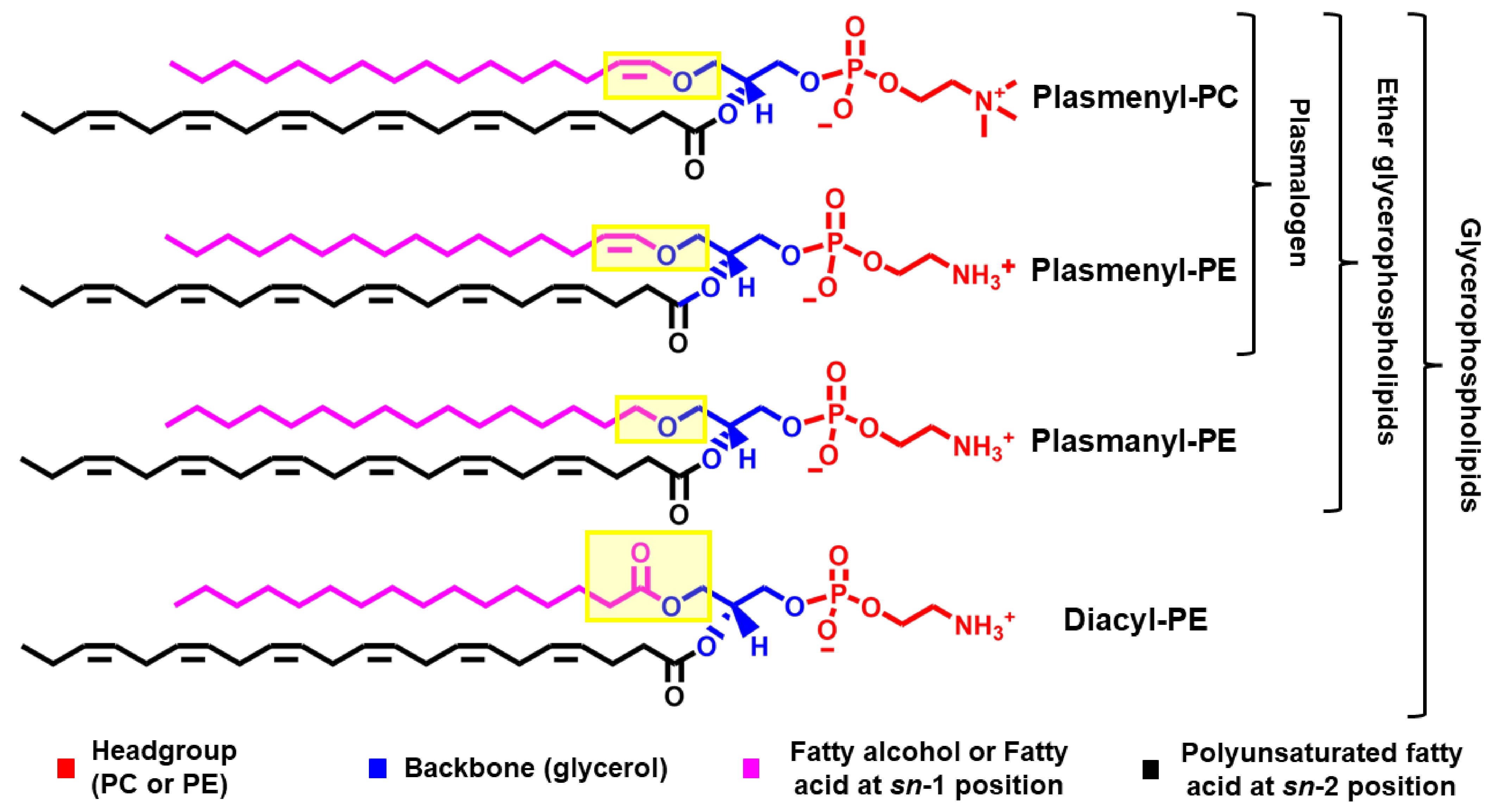

1.1. Chemical Structure

1.2. Membrane Physical Properties

1.3. Biological Properties

2. The Metabolism of Plasmalogens

3. Plasmalogen Changes in Pathophysiological Conditions

4. Plasmalogen Replacement Therapy (PRT)

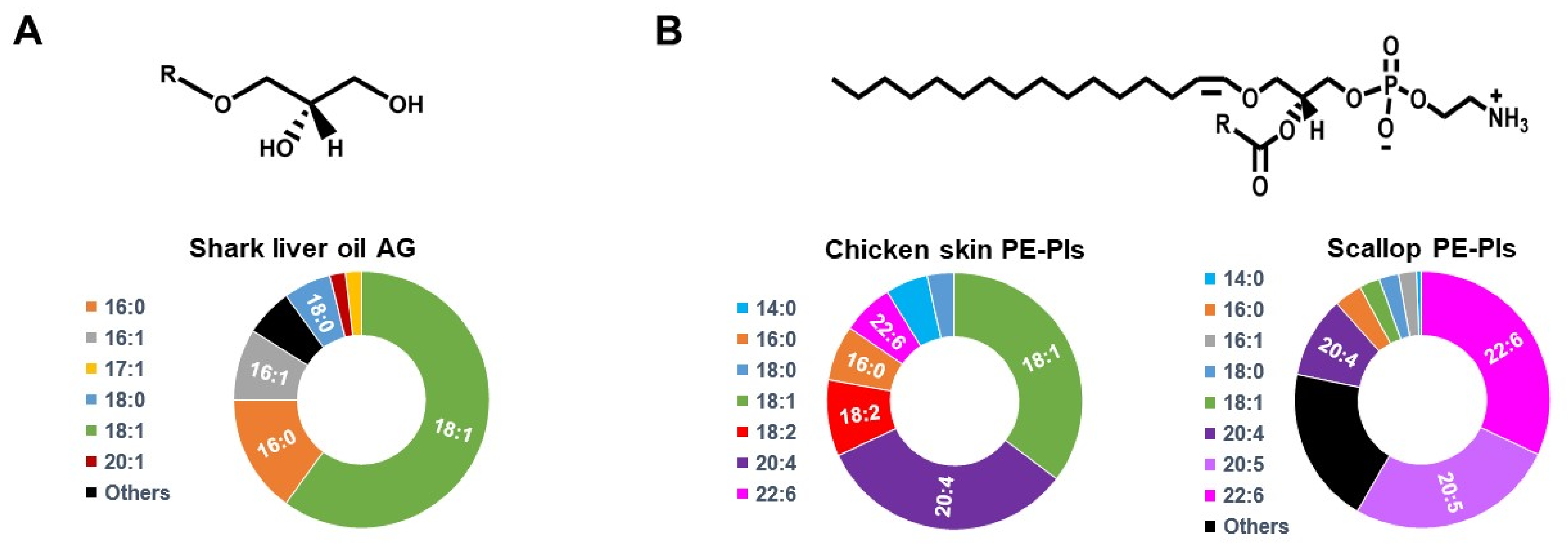

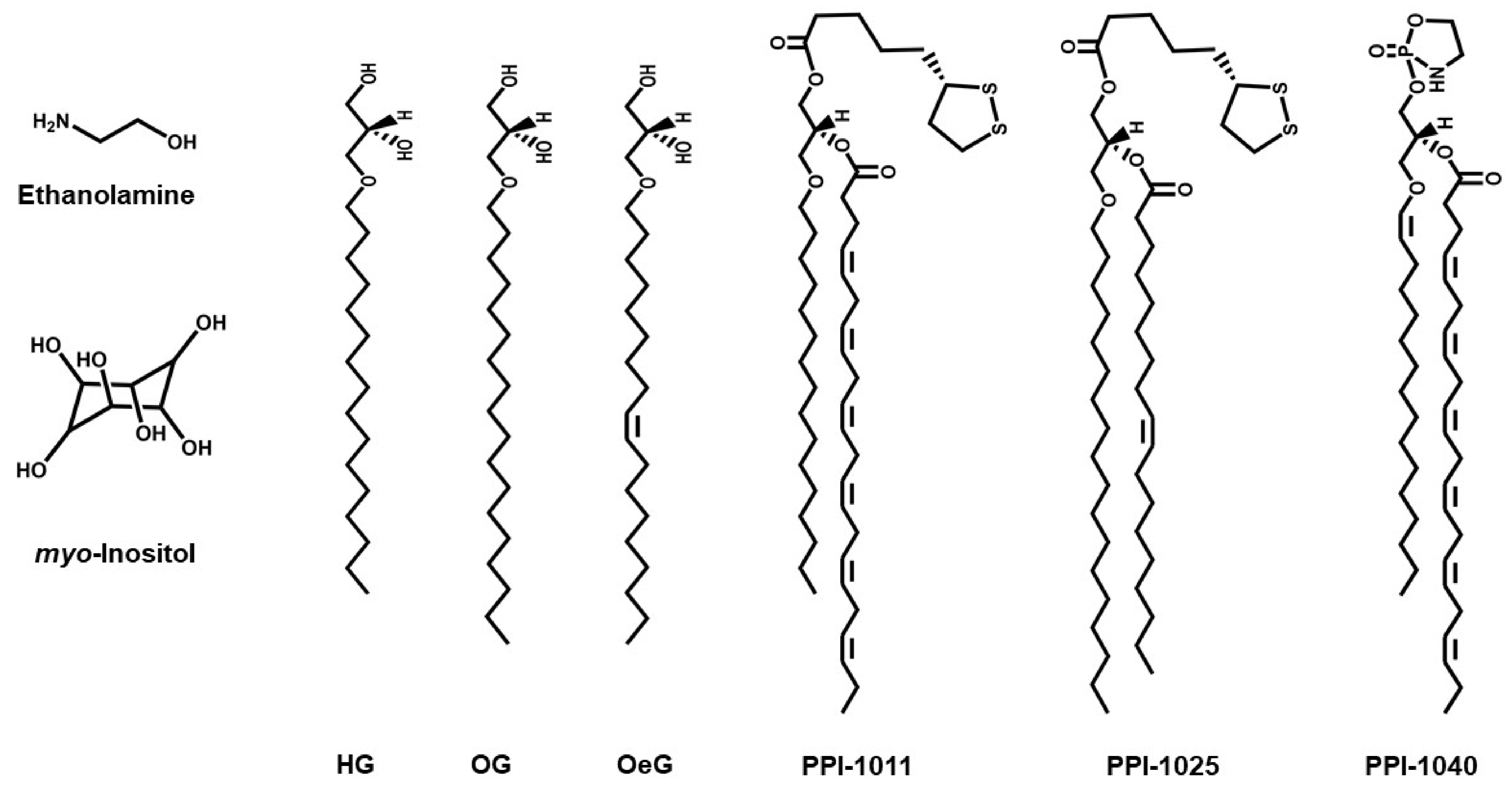

4.1. Small Molecules Used in PRT

4.2. In Vitro PRT Studies

4.3. In Vivo PRT Studies

| Pathological Condition | Model | PRT Compound | Administration | Dosage | Time | Effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipids | Phenotype | ||||||

| In Vitro | |||||||

| BTHS [100] | Lymphoblasts from patients | HG | Added to culture medium | 50 μM | 20 h | Increased PE-Pls and CL | Restored mitochondrial membrane potential |

| ZS [101] | Fibroblasts from patients | HG | Added to culture medium | 63 μM | 24 h | Increased PE-Pls | Decreased β-adrenergic signaling |

| AD [33] | Neuroinflammation in BV2/primary microglial cells | Scallop-purified PE-Pls | Added to culture medium | 6 μM | 12 h | Not reported | Inhibition of LPS-mediated TLR4 endocytosis and downstream caspase activation |

| AD [103] | Neuronal apoptosis in Neuro-2A/primary hippocampal neurons | Chicken skin-purified PE-Pls | Added to culture medium | 6–24 μM | 72 h | Not reported | Inhibition of caspase-3/9 and activation of PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK signaling pathways |

| AD [104] | Neuronal apoptosis in primary hippocampal neurons | PE-Pls (EPA-enriched) | Added to culture medium | 6–72 μM | 24 h | Not reported | Upregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins and downregulation of pro-apoptotic proteins |

| Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury [30] | Isolated rat heart | HG | Perfusion | 50 μM | 15 min | Not reported | Reduced Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury |

| In Vivo | |||||||

| PD [98] | MPTP-treated mice | PPI-1025 | Oral administration | 10–200 mg/kg | 10 days | Increased PE-Pls with octadecyl alkyl chain in serum | Prevention of MPTP-induced decrease in dopamine/serotonin |

| RDCP [99] | Pex7hypo/null mice | PPI-1040 | Oral administration | 50 mg/kg | 4 weeks | Increased PE-Pls in plasma, erythrocyteand peripheral tissue, but not in brain, lung, or kidney | Normalized hyperactive behavior |

| AD [33] | Triple transgenic mice expressing mutant APP, PS1, and Tau | Scallop-purified PE-Pls | Oral administration | 133 nM | 15 months | Not reported | Reduced endocytosis of TLR4 of the brain cortex |

| AD [104] | Aβ42-treated rats (injected in the brain) | PE-Pls (EPA-enriched) | Administered by gavage | 150 mg·kg−1· day−1 | 26 days | Not reported | Suppressed neuronal loss and enhanced BDNF/TrkB/CREB signaling |

| RCDP [105] | GNPAT knockout mice | OG | Oral administration | 2% w/v | 2 months | Increased cardiac PE-Pls | Normalized cardiac conduction velocity |

| RCDP [106] | Pex7 knockout mice | OG | Oral administration | 2% w/v | 2-4 months | Increased PE-Pls in peripheral and nervous tissues | Stopped progression of pathology in testis, adipose tissue, and eyes; nerve conduction in peripheral nerves improved |

| AD [107] | Mice (systemic LPS-induced neuroinflammation) | Chicken-breast-purified PE-Pls | Intraperitoneal injection | 20 mg/kg | 7 days | Suppressed PE-Pls reduction in the PFC and hippocampus | Attenuated microglia activation and accumulation of Aβ proteins |

| AD [108] | Aβ42-treated rats (injected in the brain) | PE-Pls (EPA-enriched) | Administered by gavage | 150 mg·kg−1· day−1 | 26 days | Not reported | Alleviated Aβ-induced neurotoxicity by inhibiting oxidative stress, neuronal injury, apoptosis, and neuro-inflammation |

| AD [109] | Aβ-infused rats | Ascidian-purified PE-Pls | Oral administration | 209 μmol·kg−1·day−1 | 4 weeks | Increased PE-Pls in plasma, erythrocyte, and liver | Improvement in reference and working memory-related learning abilities |

| PD [110] | MPTP-treated mice | PPI-1011 | Oral administration | 5–50 mg·kg−1 | 10 days | Increased PE-Pls with octadecyl alkyl chain in serum | Prevention of MPTP-induced decrease in dopamine/serotonin |

| PD [111] | MPTP monkeys | PPI-1011 | Oral administration | 50 mg·kg−1 | 12 days | Increased serum PE-Pls | Decreased L-DOPA-induced dyskinesias |

| PD [112] | MPTP-treated mice | PPI-1011 | Administered by gavage | 10–200 mg·kg−1 | 10 days | Increased plasma PE-Pls | Prevented loss of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) expression and reduced the infiltration of macrophages in the gut |

| PD [112] | MPTP monkeys | PPI-1011 | Oral administration | 25 mg·kg−1 | 28 days | Not reported | Reduced L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia |

| Atherosclerosis [113] | Hamster (High-fat diet) | Sea urchin-purified PE-Pls | Dietary supplementation | 0.03% | 8 weeks | Decreased total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol | Reduced atherosclerotic lesion area, attenuated the degree of liver steatosis |

| Atherosclerosis [104] | LDL receptor-deficient mice (High-fat diet) | Sea cucumber-purified PE-Pls | Dietary supplementation | 0.01% | 8 weeks | Decreased total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol; Increased total neutral sterol and bile acids in feces | Reduced atherosclerotic lesion area |

| Cardiac remodeling [114] | Dominant negative PI3K (small heart) and overexpression of mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1 (dilated cardiomyopathy) transgenic mice | OG | Dietary supplementation | 2 g·kg−1· day−1 | 16 weeks | Increased PE-Pls in the heart | No effect on heart function and size |

| Cancer [115] | Grafted tumors in mice | AG purified (from shark liver oil) | Dietary supplementation | 25 mg·day−1 | 10 days | Decreased plasmalogen content in tumor | Decreased growth, vascularization, and dissemination of Lewis lung carcinoma |

| Clinical Trials | |||||||

| Peroxisomal disorder [90] | 3 human subjects with low DHAT-AT activity and erythrocyte PE-Pls | OG | Ether lipid suspension | 5–10 mg/kg−1· day−1 | 27–43 month | Increased erythrocyte PE-Pls | Improvement in nutritional status, liver function, retinal pigmentation, and motor tone |

| Peroxisomal disorder [116] | 2 human subjects with low DHAT-AT activity and erythrocyte PE-Pls | OG | Ether lipid suspension | 20 mg/kg−1· day−1 | 3–18 months | Increased erythrocyte PE-Pls | Improved growth, muscle tone, general state of awareness |

| Mild-AD and mild cognitive impairment [117] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial with 328 subjects with 20–27 points in MMSE-J and ≤5 points in GDS-S-J | Scallop-purified PE-Pls | Oral administration | 1 mg/day | 24 weeks | Treatment had lowered the decrease in plasma PE-Pls | No significant differences in primary and secondary outcomes. Subgroup analysis of mild-AD patients, showed improvement in WMS-R (secondary outcome) in females and those aged below 77 years |

| Mild forgetfulness [118] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial with 50 adult volunteers | Ascidian-purified PE-Pls | Dietary supplementation | 1 mg/day | 12 weeks | Not reported | Increased score in composite memory (sum of verbal and visual memory scores) |

| Metabolic disease [118] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over clinical trial with 10 (obese or overweight) subjects | Shark liver oil-purified AG | Oral administration | 4 g/day | 3 weeks treatment/ 3 weeks washout/ 3 weeks placebo (and vice versa) | Increased in PE-Pls and ether lipids in plasma and white blood cells | Decreased plasma levels of total free-cholesterol, triglycerides, and C-reactive protein |

| Hyperlipidemia/Metabolic disease [119] | 17 subjects with obesity and hyperlipidemia | Myo-inositol | Oral administration | 5 g/day in week 1 and 10 g/day in week 2 | 2 weeks | Increased plasma PC-Pls | Decreased in atherogenic cholesterol, including small dense LDL |

| PD [71] | 10 subjects with PD | Scallop-purified PE-Pls | Oral administration | 1 mg/day | 24 weeks | Increased PE-Pls in plasma and erythrocyte membranes | Improvement clinical symptoms (as evaluated by PDQ-39) |

4.4. Clinical Trials

5. Future Perspective for PRT

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | arachidonic acid |

| AADHAP-R | acyl/alkyl-DHAP reductase |

| AAG3P-AT | lysophosphatidate acyltransferase |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AG | alkylglycerols |

| AGP | 1-alkyl-2-lyso-sn-glycero-3-phosphate |

| AGPS | Alkyl-DHAP synthase |

| AKT | protein kinase B |

| BTHS | Barth syndrome |

| CAD | coronary artery diseases |

| DHA | docosahexaenoic acid |

| DHAP | dihydroxyacetone phosphate |

| EPA | eicosapentaenoic acid |

| EPT | ethanolamine phosphotransferase |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| ERK | extracellular signal-regulated kinases |

| Far1 | fatty acyl-CoA reductase 1 |

| GNPAT | glyceronephosphate O-acyltransferase |

| HG | 1-O-hexadecyl-sn-glycerol |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MPTP | 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine |

| OeG | 1-O-octadecenyl-sn-glycerol |

| OG | 1-O-octadecyl-sn-glycerol |

| PAP-1 | phosphatidate phosphohydrolase 1 |

| PC | phosphatidylcholine |

| PC-Pls | plasmenyl-PC |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PE | phosphatidylethanolamine |

| PEDS1 | plasmanylethanolamine desaturase 1 |

| PE-Pls | plasmenyl-PE |

| Pex7 | peroxisomal biogenesis factor 7 |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PLA2 | phospholipase A2 |

| PLC | phospholipase C |

| PLD | phospholipase D |

| pPA | plasmanyl phosphatidic acid |

| pPE | plasmanyl ethanolamine |

| PPI-1011 | an alkyl-diacyl plasmalogen precursor with DHA at the sn-2 position |

| PPI-1025 | an alkyl-diacyl plasmalogen precursor with oleoyl at the sn-2 position |

| PPI-1040 | a PE-Pls analog with a proprietary cyclic PE headgroup |

| PRT | plasmalogen replacement therapy |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| RCDP | rhizomelic chondrodysplasia punctata |

| RNS | reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| ZS | Zellweger Syndrome |

References

- Harayama, T.; Riezman, H. Understanding the Diversity of Membrane Lipid Composition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braverman, N.E.; Moser, A.B. Functions of Plasmalogen Lipids in Health and Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Mol. Basis Dis. 2012, 1822, 1442–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paul, S.; Lancaster, G.I.; Meikle, P.J. Plasmalogens: A Potential Therapeutic Target for Neurodegenerative and Cardiometabolic Disease. Prog. Lipid Res. 2019, 74, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristina, M.; Messias, F.; Mecatti, G.C.; Priolli, D.G.; De, P.; Carvalho, O. Plasmalogen Lipids: Functional Mechanism and Their Involvement in Gastrointestinal Cancer. Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, J.; Lackner, K.; Wohlfarter, Y.; Sailer, S.; Zschocke, J.; Werner, E.R.; Watschinger, K.; Keller, M.A. Unequivocal Mapping of Molecular Ether Lipid Species by LC−MS/MS in Plasmalogen-Deficient Mice. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 11268–11276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, B. Analytical Methods for (Oxidized) Plasmalogens: Methodological Aspects and Applications. Free. Radic. Res. 2015, 49, 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivuniemi, A. The Biophysical Properties of Plasmalogens Originating from Their Unique Molecular Architecture. FEBS Lett. 2017, 591, 2700–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgas, K.; Teigler, A.; Komljenovic, D.; Just, W.W. The Ether Lipid-Deficient Mouse: Tracking down Plasmalogen Functions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Mol. Cell Res. 2006, 1763, 1511–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, X.; Gross, R.W. Plasmenylcholine and Phosphatidylcholine Membrane Bilayers Possess Distinct Conformational Motifs. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 4992–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malthaner, M.; Hermetter, A.; Paltauf, F.; Seelig, J. Structure and Dynamics of Plasmalogen Model Membranes Containing Cholesterol: A Deuterium NMR Study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Biomembr. 1987, 900, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malthaner, M.; Seelig, J.; Johnston, N.C.; Goldfine, H. Deuterium Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Studies on the Plasmalogens and the Glycerol Acetals of Plasmalogens of Clostridium butyricum and Clostridium beijerinckii. Biochemistry 1987, 26, 5826–5833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaby, J.M.; Schmid, P.C.; Brockman, H.L.; Hermetter, A.; Paltauf, F. Packing of Ether and Ester Phospholipids in Monolayers. Evidence for Hydrogen-Bonded Water at the Sn-1 Acyl Group of Phosphatidylcholines. Biochemistry 1983, 22, 5808–5813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rog, T.; Koivuniemi, A. The Biophysical Properties of Ethanolamine Plasmalogens Revealed by Atomistic Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Biomembr. 2016, 1858, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janmey, P.A.; Kinnunen, P.K.J. Biophysical Properties of Lipids and Dynamic Membranes. Trends Cell Biol. 2006, 16, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, L.J.; Han, X.; Chung, K.N.; Gross, R.W. Lipid Rafts Are Enriched in Arachidonic Acid and Plasmenylethanolamine and Their Composition Is Independent of Caveolin-1 Expression: A Quantitative Electrospray Ionization/Mass Spectrometric Analysis. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 2075–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbari, F.; McCaskill, J.; Coakley, G.; Millar, M.; Maizels, R.M.; Fabriás, G.; Casas, J.; Buck, A.H. Plasmalogen Enrichment in Exosomes Secreted by a Nematode Parasite versus Those Derived from Its Mouse Host: Implications for Exosome Stability and Biology. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2016, 5, 30741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulodziecka, K.; Diaz-Rohrer, B.B.; Farley, M.M.; Chan, R.B.; Paolo, G.D.; Levental, K.R.; Neal Waxham, M.; Levental, I. Remodeling of the Postsynaptic Plasma Membrane during Neural Development. Mol. Biol. Cell 2016, 27, 3480–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, A.E.; Goldfine, H.; Narayan, O.; Gruner, S.M. Physical Studies on the Membranes and Lipids of Plasmalogen-Deficient Megasphaera Elsdenii. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1990, 55, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohner, K. Is the High Propensity of Ethanolamine Plasmalogens to Form Non-Lamellar Lipid Structures Manifested in the Properties of Biomembranes? Chem. Phys. Lipids 1996, 81, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohner, K.; Hermetter, A.; Paltauf, F. Phase Behavior of Ethanolamine Plasmalogen. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1984, 34, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohner, K.; Balgavy, P.; Hermetter, A.; Paltauf, F.; Laggner, P. Stabilization of Non-Bilayer Structures by the Etherlipid Ethanolamine Plasmalogen. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Biomembr. 1991, 1061, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, T.P.; Rodemer, C.; Jauch, A.; Hunziker, A.; Moser, A.; Gorgas, K.; Just, W.W. Impaired Membrane Traffic in Defective Ether Lipid Biosynthesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reiss, D.; Beyer, K.; Engelmann, B. Delayed Oxidative Degradation of Polyunsaturated Diacyl Phospholipids in the Presence of Plasmalogen Phospholipids in Vitro. Biochem. J. 1997, 323, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hahnel, D.; Beyer, K.; Engelmann, B. Inhibition of Peroxyl Radical-Mediated Lipid Oxidation by Plasmalogen Phospholipids and α-Tocopherol. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 27, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahnel, D.; Huber, T.; Kurze, V.; Beyer, K.; Engelmann, B. Contribution of Copper Binding to the Inhibition of Lipid Oxidation by Plasmalogen Phospholipids. Biochem. J. 1999, 340, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoellers, R.A.; Morandq, O.H.; Raetzll, C.R.H. A Possible Role for Plasmalogens in Protecting Animal Cells against Photosensitized Killing. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 11590–11596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagan, N.; Zoeller, R.A. Plasmalogens: Biosynthesis and Functions. Prog. Lipid Res. 2001, 40, 199–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoeller, R.A.; Grazia, T.J.; Lacamera, P.; Park, J.; Gaposchkin, D.P.; Farber, H.W.; Lacam-Era, P. Increasing Plasmalogen Levels Protects Human Endothelial Cells during Hypoxia Increasing Plasmalogen Levels Protects Hu-Man Endothelial Cells during Hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002, 283, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khan, M.; Singh, J.; Singh, I. Plasmalogen Deficiency in Cerebral Adrenoleukodystrophy and Its Modulation by Lovastatin. J. Neurochem. 2008, 106, 1766–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maulik, N.; Tosaki, A.; Engelman, R.M.; Cordis, G.A.; Das, D.K. Myocardial Salvage by 1-O-Hexadecyl-Sn-Glycerol: Possible Role of Peroxisomal Dysfunction in Ischemia Reperfusion Injury. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1994, 24, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindelar, P.J.; Guan, Z.; Dallner, G.; Ernster, L. The Protective Role of Plasmalogens in Iron-Induced Lipid Peroxidation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dott, W.; Mistry, P.; Wright, J.; Cain, K.; Herbert, K.E. Modulation of Mitochondrial Bioenergetics in a Skeletal Muscle Cell Line Model of Mitochondrial Toxicity. Redox Biol. 2014, 2, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ali, F.; Hossain, M.S.; Sejimo, S.; Akashi, K. Plasmalogens Inhibit Endocytosis of Toll-like Receptor 4 to Attenuate the Inflammatory Signal in Microglial Cells. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 56, 3404–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.S.; Mineno, K.; Katafuchi, T. Neuronal Orphan G-Protein Coupled Receptor Proteins Mediate Plasmalogens-Induced Activation of ERK and Akt Signaling. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150846. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, M.; Ibrahim, A.; Akashi, K.; Hossain, M.S. PUFA-Plasmalogens Attenuate the LPS-Induced Nitric Oxide Production by Inhibiting the NF-KB, P38 MAPK and JNK Pathways in Microglial Cells. Neuroscience 2019, 397, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorninger, F.; Forss-Petter, S.; Wimmer, I.; Berger, J. Plasmalogens, Platelet-Activating Factor and beyond—Ether Lipids in Signaling and Neurodegeneration. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 145, e105061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, J.M.; Astudillo, A.M.; Casas, J.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Regulation of Phagocytosis in Macrophages by Membrane Ethanolamine Plasmalogens. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palladino, E.N.D.; Katuga, L.A.; Kolar, G.R.; Ford, D.A. 2-Chlorofatty Acids: Lipid Mediators of Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation. J. Lipid Res. 2018, 59, 1424–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thukkani, A.K.; Albert, C.J.; Wildsmith, K.R.; Messner, M.C.; Martinson, B.D.; Hsu, F.F.; Ford, D.A. Myeloperoxidase-Derived Reactive Chlorinating Species from Human Monocytes Target Plasmalogens in Low Density Lipoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 36365–36372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lan, M.; Lu, W.; Zou, T.; Li, L.; Liu, F.; Cai, T.; Cai, Y. Role of Inflammatory Microenvironment: Potential Implications for Improved Breast Cancer Nano-Targeted Therapy. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 2105–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Henry, W.S.; Ricq, E.L.; Graham, E.T.; Phadnis, V.; Maretich, P.; Paradkar, S.; Boehnke, N.; Deik, A.A.; Reinhardt, F.; et al. Plasticity of Ether Lipids Promotes Ferroptosis Susceptibility and Evasion. Nature 2020, 585, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Liu, D.; Gu, W.; Chu, B. Peroxisome-Driven Ether-Linked Phospholipids Biosynthesis Is Essential for Ferroptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 2536–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Meer, G.; Voelker, D.R.; Feigenson, G.W. Membrane Lipids: Where They Are and How They Behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.T.H.; Sharon-Friling, R.; Ivanova, P.; Milne, S.B.; Myers, D.S.; Rabinowitz, J.D.; Brown, H.A.; Shenk, T. Synaptic Vesicle-like Lipidome of Human Cytomegalovirus Virions Reveals a Role for SNARE Machinery in Virion Egress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 12869–12874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gerl, M.J.; Sampaio, J.L. Quantitative analysis of the lipidome of the influenza virus envelope and MDCK cell apical membrane. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 196, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wanders, R.J.A. Metabolic Functions of Peroxisomes in Health and Disease. Biochimie 2014, 98, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brites, P.; Waterham, H.R.; Wanders, R.J.A. Functions and Biosynthesis of Plasmalogens in Health and Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2004, 1636, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, E.R.; Keller, M.A.; Sailer, S.; Lackner, K.; Koch, J.; Hermann, M.; Coassin, S.; Golderer, G.; Werner-Felmayer, G.; Zoeller, R.A.; et al. The TMEM189 Gene Encodes Plasmanylethanolamine Desaturase Which Introduces the Characteristic Vinyl Ether Double Bond into Plasmalogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 7792–7798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Honsho, M.; Fujiki, Y. Plasmalogen Homeostasis—Regulation of Plasmalogen Biosynthesis and Its Physiological Consequence in Mammals. FEBS Lett. 2017, 591, 2720–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Honsho, M.; Abe, Y.; Fujiki, Y. Plasmalogen Biosynthesis Is Spatiotemporally Regulated by Sensing Plasmalogens in the Inner Leaflet of Plasma Membranes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Honsho, M.; Asaoku, S.; Fujiki, Y. Posttranslational Regulation of Fatty Acyl-CoA Reductase 1, Far1, Controls Ether Glycerophospholipid Synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 8537–8542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Honsho, M.; Asaoku, S.; Fukumoto, K.; Fujiki, Y. Topogenesis and Homeostasis of Fatty Acyl-CoA Reductase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 34588–34598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wolfs, R.A.; Gross, R.W. Identification of Neutral Active Phospholipase C Which Hydrolyzes Choline Glycerophospholipids and Plasmalogen Selective Phospholipase AP in Canine Myocardium. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 7295–7303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Iderstine, S.C.; Byers, D.M.; Ridgway, N.D.; Cook, H.W. Phospholipase D Hydrolysis of Plasmalogen and Diacyl Ethanolamine Phosphoglycerides by Protein Kinase C Dependent and Independent Mechanisms. J. Lipid Mediat. Cell Signal. 1997, 15, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, S.L.; Stuppy, R.J.; Gross, R.W. Purification and Characterization of Canine Myocardial Cytosolic Phospholipase A2. A Calcium-Independent Phospholipase with Absolute Sn-2 Regiospecificity for Diradyl Glycerophospholipids. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 10622–10630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, D.A.; Hazen, S.L.; Saffitz, J.E.; Gross, R.W. The Rapid and Reversible Activation of a Calcium-Independent Plasmalogen-Selective Phospholipase A2 during Myocardial Ischemia. J. Clin. Investig. 1991, 88, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, H.C.; Farooqui, A.A.; Horrocks, L.A. Plasmalogen-Selective Phospholipase A2 and Its Role in Signal Transduction. J. Lipid Mediat. Cell Signal 1996, 14, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.C.; Farooqui, A.A.; Horrocks, L.A. Characterization of Plasmalogen-Selective Phospholipase A2 from Bovine Brain. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1997, 416, 309–313. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, C.M.; Yang, K.; Liu, G.; Moon, S.H.; Dilthey, B.G.; Gross, R.W. Cytochrome c Is an Oxidative Stress–Activated Plasmalogenase That Cleaves Plasmenylcholine and Plasmenylethanolamine at the sn-1 Vinyl Ether Linkage. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 8693–8709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Farooqui, A.A.; Farooqui, T.; Horrocks, L.A. Biosynthesis of Plasmalogens in Brain. In Metabolism and Functions of Bioactive Ether Lipids in the Brain; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rouser, G.; Yamamoto, A. Curvilinear Regression Course of Human Brain Lipid Composition Changes with Age. Lipids 1968, 3, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeba, R.; Maeda, T.; Kinoshita, M.; Takao, K.; Takenaka, H.; Kusano, J.; Yoshimura, N.; Takeoka, Y.; Yasuda, D.; Okazaki, T.; et al. Plasmalogens in Human Serum Positively Correlate with High-Density Lipoprotein and Decrease with Aging. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2007, 14, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steinberg, S.J.; Raymond, G.V.; Braverman, N.E.; Moser, A.B. Zellweger Spectrum Disorder. In Gene Reviews® [Internet]; Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J.H., Mirzaa, G., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2020; pp. 1993–2021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bams-Mengerink, A.M.; Koelman, J.H.T.M.; Waterham, H.; Barth, P.G.; Poll-The, B.T. The Neurology of Rhizomelic Chondrodysplasia Punctata. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2013, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heymans, H.S.A.; Schutgens, R.B.H.; Tan, R.; van den Bosch, H.; Borst, P. Severe Plasmalogen Deficiency in Tissues of Infants without Peroxisomes (Zellweger Syndrome). Nature 1983, 306, 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorninger, F.; Brodde, A.; Braverman, N.E.; Moser, A.B.; Just, W.W.; Forss-Petter, S.; Brügger, B.; Berger, J. Homeostasis of Phospholipids—The Level of Phosphatidylethanolamine Tightly Adapts to Changes in Ethanolamine Plasmalogens. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2014, 1851, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ginsberg, L.; Rafique, S.; Xuereb, J.H.; Rapoport, S.I.; Gershfeld, N.L. Disease and Anatomic Specificity of Ethanolamine Plasmalogen Deficiency in Alzheimer’s Disease Brain. Brain Res. 1995, 698, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanow, C.W.; Stern, M.B.; Sethi, K. The Scientific and Clinical Basis for the Treatment of Parkinson Disease (2009). Neurology 2009, 72, S1–S136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, W.J.; Chen, W.W.; Zhang, X. Multiple Sclerosis: Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatments (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 13, 3163–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, X.; Holtzman, D.M.; McKeel, D.W. Plasmalogen Deficiency in Early Alzheimer’s Disease Subjects and in Animal Models: Molecular Characterization Using Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. J. Neurochem. 2001, 77, 1168–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawatari, S.; Ohara, S.; Taniwaki, Y.; Tsuboi, Y.; Maruyama, T.; Fujino, T. Improvement of Blood Plasmalogens and Clinical Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease by Oral Administration of Ether Phospholipids: A Preliminary Report. Parkinsons Dis. 2020, 2020, e2671070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bione, S.; D’Adamo, P.; Maestrini, E.; Gedeon, A.K.; Bolhuis, P.A.; Toniolo, D. A Novel X-Linked Gene, G4.5. Is Responsible for Barth Syndrome. Nat. Genet. 1996, 12, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, I.; Klingenberg, R.; Othman, A.; Rohrer, L.; Landmesser, U.; Heg, D.; Rodondi, N.; Mach, F.; Windecker, S.; Matter, C.M.; et al. Decreased Phosphatidylcholine Plasmalogens—A Putative Novel Lipid Signature in Patients with Stable Coronary Artery Disease and Acute Myocardial Infarction. Atherosclerosis 2016, 246, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozelli, J.C., Jr.; Epand, R.M. Interplay between cardiolipin and plasmalogens in Barth Syndrome. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, T.; Kimura, A.K.; Ren, M.; Berno, B.; Xu, Y.; Schlame, M.; Epand, R.M. Substantial Decrease in Plasmalogen in the Heart Associated with Tafazzin Deficiency. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 2162–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kimura, T.; Kimura, A.K.; Ren, M.; Monteiro, V.; Xu, Y.; Berno, B.; Schlame, M.; Epand, R.M. Plasmalogen Loss Caused by Remodeling Deficiency in Mitochondria. Life Sci. Alliance 2019, 2, e201900348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meikle, P.J.; Wong, G.; Tsorotes, D.; Barlow, C.K.; Weir, J.M.; Christopher, M.J.; MacIntosh, G.L.; Goudey, B.; Stern, L.; Kowalczyk, A.; et al. Plasma Lipidomic Analysis of Stable and Unstable Coronary Artery Disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 2723–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bozelli, J.C., Jr.; Azher, S.; Epand, R.M. Plasmalogen and chronic inflammatory diseases. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 730829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moxon, J.V.; Jones, R.E.; Wong, G.; Weir, J.M.; Mellett, N.A.; Kingwell, B.A.; Meikle, P.J.; Golledge, J. Baseline Serum Phosphatidylcholine Plasmalogen Concentrations Are Inversely Associated with Incident Myocardial Infarction in Patients with Mixed Peripheral Artery Disease Presentations. Atherosclerosis 2017, 263, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeba, R.; Kojima, K.-I.; Nagura, M.; Komori, A.; Nishimukai, M.; Okazaki, T.; Uchida, S. Association of Cholesterol Efflux Capacity with Plasmalogen Levels of High-Density Lipoprotein: A Cross-Sectional Study in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. Atherosclerosis 2018, 270, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaddurah-Daouk, R.; McEvoy, J.; Baillie, R.; Zhu, H.; Yao, J.K.; Nimgaonkar, V.L.; Buckley, P.F.; Keshavan, M.S.; Georgiades, A.; Nasrallah, H.A. Impaired Plasmalogens in Patients with Schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 198, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikuta, A.; Sakurai, T.; Nishimukai, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Nagasaka, A.; Hui, S.-P.; Hara, H.; Chiba, H. Composition of Plasmalogens in Serum Lipoproteins from Patients with Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis and Their Susceptibility to Oxidation. Clin. Chim. Acta 2019, 493, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Zhou, J.; Yang, S.; Li, H.; Wang, C.; Fang, X.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Han, X.; Wen, C. Oxidative Stress Leads to Reduction of Plasmalogen Serving as a Novel Biomarker for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 101, 475–481. [Google Scholar]

- Fujino, T.; Hossain, M.S.; Mawatari, S. Therapeutic Efficacy of Plasmalogens for Alzheimer’s Disease, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Parkinson’s Disease in Conjunction with a New Hypothesis for the Etiology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1299, 195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Maeba, R.; Yamazaki, Y.; Nezu, T.; Nishimukai, M.; Okazaki, T.; Hara, H. Serum Choline Plasmalogen Is a Novel Biomarker for Metabolic Syndrome and Atherosclerosis. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2011, 164, S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimukai, M.; Maeba, R.; Yamazaki, Y.; Nezu, T.; Sakurai, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Hui, S.-P.; Chiba, H.; Okazaki, T.; Hara, H. Serum Choline Plasmalogens, Particularly Those with Oleic Acid in Sn-2, Are Associated with Proatherogenic State. J. Lipid Res. 2014, 55, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Escribá, P.V. Membrane-Lipid Therapy: A New Approach in Molecular Medicine. Trends Mol. Med. 2006, 12, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, G.L.; Ash, M.E. Lipid Replacement Therapy: A Natural Medicine Approach to Replacing Damaged Lipids in Cellular Membranes and Organelles and Restoring Function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Biomembr. 2014, 1838, 1657–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Escribá, P.V.; Busquets, X.; Inokuchi, J.I.; Balogh, G.; Török, Z.; Horváth, I.; Harwood, J.L.; Vígh, L. Membrane Lipid Therapy: Modulation of the Cell Membrane Composition and Structure as a Molecular Base for Drug Discovery and New Disease Treatment. Prog. Lipid Res. 2015, 59, 38–53. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.K.; Holmes, R.D.; Wilson, G.N.; Hajra, A.K. Dietary Ether Lipid Incorporation into Tissue Plasmalogens of Humans and Rodents. Lipids 1992, 27, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Jia, J.; Chiba, H.; Hui, S.-P. Quantitative and Comparative Investigation of Plasmalogen Species in Daily Foodstuffs. Foods 2021, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Alexander, A.; Smith, T.; Culham, K.; Gunawan, K.A.; Weir, J.M.; Cinel, M.A.; Jayawardana, K.S.; Mellett, N.A.; Lee, M.K.S.; et al. Shark Liver Oil Supplementation Enriches Endogenous Plasmalogens and Reduces Markers of Dyslipidemia and Inflammation. J. Lipid Res. 2021, 62, e100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawatari, S.; Katafuchi, T.; Miake, K.; Fujino, T. Dietary plasmalogen increases erythrocyte membrane plasmalogen in rats. Lipids Health Dis. 2012, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Snyder, F. Alkylglycerol Phosphotransferase. Methods Enzymol. 1992, 209, 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Paltauf, F. Intestinal Uptake and Metabolism of Alkyl Acyl Glycerophospholipids and of Alkyl Glycerophospholipids in the Rat Biosynthesis of Plasmalogens from [3H]Alkyl Glycerophosphoryl [14C]Ethanolamine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Lipids Lipid Metab. 1972, 260, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Hajra, A.K. High Incorporation of Dietary 1-O-Heptadecyl Glycerol into Tissue Plasmalogens of Young Rats. FEBS Lett. 1988, 227, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wood, P.L.; Smith, T.; Lane, N.; Khan, M.A.; Ehrmantraut, G.; Goodenowe, D.B. Oral Bioavailability of the Ether Lipid Plasmalogen Precursor, PPI-1011, in the Rabbit: A New Therapeutic Strategy for Alzheimer’s Disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2011, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miville-Godbout, E.; Bourque, M.; Morissette, M.; Al-Sweidi, S.; Smith, T.; Jayasinghe, D.; Ritchie, S.; di Paolo, T. Plasmalogen Precursor Mitigates Striatal Dopamine Loss in MPTP Mice. Brain Res. 2017, 1674, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallatah, W.; Smith, T.; Cui, W.; Jayasinghe, D.; di Pietro, E.; Ritchie, S.A.; Braverman, N. Oral Administration of a Synthetic Vinyl-Ether Plasmalogen Normalizes Open Field Activity in a Mouse Model of Rhizomelic Chondrodysplasia Punctata. Dis. Models Mech. 2020, 13, dmm042499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bozelli, J.C.; Lu, D.; Atilla-Gokcumen, G.E.; Epand, R.M. Promotion of Plasmalogen Biosynthesis Reverse Lipid Changes in a Barth Syndrome Cell Model. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2020, 1865, e158677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styger, R.; Wiesmann, U.N.; Honegger, U.E. Plasmalogen Content and β-Adrenoceptor Signalling in Fibroblasts from Patients with Zellweger Syndrome. Effects of Hexadecylglycerol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2002, 1585, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, X.; Cong, P.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, J.; Xue, C. Preparation and Effects on Neuronal Nutrition of Plasmenylethonoamine and Plasmanylcholine from the Mussel Mytilus Edulis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2020, 84, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.S.; Ifuku, M.; Take, S.; Kawamura, J.; Miake, K. Plasmalogens Rescue Neuronal Cell Death through an Activation of AKT and ERK Survival Signaling. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, H.; Zhang, L.; Ding, L.; Xie, W.; Jiang, X.; Xue, C.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y. EPA-Enriched Ethanolamine Plasmalogen and EPA-Enriched Phosphatidylethanolamine Enhance BDNF/TrkB/CREB Signaling and Inhibit Neuronal Apoptosis in Vitro and in Vivo. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 1729–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todt, H.; Dorninger, F.; Rothauer, P.J.; Fischer, C.M.; Schranz, M.; Bruegger, B.; Lüchtenborg, C.; Ebner, J.; Hilber, K.; Koenig, X.; et al. Oral Batyl Alcohol Supplementation Rescues Decreased Cardiac Conduction in Ether Phospholipid-Deficient Mice. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2020, 43, 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brites, P.; Ferreira, A.S.; da Silva, T.F.; Sousa, V.F.; Malheiro, A.R.; Duran, M.; Waterham, H.R.; Baes, M.; Wanders, R.J.A. Alkyl-Glycerol Rescues Plasmalogen Levels and Pathology of Ether-Phospholipid Deficient Mice. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28539. [Google Scholar]

- Ifuku, M.; Katafuchi, T.; Mawatari, S.; Noda, M.; Miake, K.; Sugiyama, M.; Fujino, T. Anti-Inflammatory/Anti-Amyloidogenic Effects of Plasmalogens in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Neuroinflammation in Adult Mice. J. Neuroinflamm. 2012, 9, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Che, H.; Li, Q.; Zhang, T.; Ding, L.; Zhang, L.; Shi, H.; Yanagita, T.; Xue, C.; Chang, Y.; Wang, Y. A Comparative Study of EPA-Enriched Ethanolamine Plasmalogen and EPA-Enriched Phosphatidylethanolamine on Aβ42 Induced Cognitive Deficiency in a Rat Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 3008–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, S.; Hashimoto, M.; Haque, A.M.; Nakagawa, K.; Kinoshita, M.; Shido, O.; Miyazawa, T. Oral Administration of Ethanolamine Glycerophospholipid Containing a High Level of Plasmalogen Improves Memory Impairment in Amyloid β-Infused Rats. Lipids 2017, 52, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miville-Godbout, E.; Bourque, M.; Morissette, M.; Al-Sweidi, S.; Smith, T.; Mochizuki, A.; Senanayake, V.; Jayasinghe, D.; Wang, L.; Goodenowe, D.; et al. Plasmalogen Augmentation Reverses Striatal Dopamine Loss in MPTP Mice. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, L.; Smith, T.; Senanayake, V.; Mochizuki, A.; Miville-Godbout, E.; Goodenowe, D.; Paolo, T.D. Plasmalogen Precursor Analog Treatment Reduces Levodopa-Induced Dyskinesias in Parkinsonian Monkeys. Behav. Brain Res. 2015, 286, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, J.; Smith, T.; Lamontagne-Proulx, J.; Bourque, M.; al Sweidi, S.; Jayasinghe, D.; Ritchie, S.; Paolo, T.D.; Soulet, D. Neuroprotection and Immunomodulation in the Gut of Parkinsonian Mice with a Plasmalogen Precursor. Brain Res. 2019, 1725, e146460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Q.; Wang, X.; Cong, P.; Xu, J.; Xue, C. Lipidomics Approach in High-Fat-Diet-Induced Atherosclerosis Dyslipidemia Hamsters: Alleviation Using Ether-Phospholipids in Sea Urchin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 9167–9177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, Y.K.; Huynh, K.; Mellett, N.A.; Henstridge, D.C.; Kiriazis, H.; Ooi, J.Y.Y.; Matsumoto, A.; Patterson, N.L.; Sadoshima, J.; Meikle, P.J.; et al. Distinct Lipidomic Profiles in Models of Physiological and Pathological Cardiac Remodeling, and Potential Therapeutic Strategies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2018, 1863, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrono, F.; Martin, B.; Leduc, C.; le Lan, J.; Saiag, B.; Legrand, P.; Moulinoux, J.-P.; Legrand, A.B.; Pédrono, F.; Martin, B.; et al. Natural Alkylglycerols Restrain Growth and Metastasis of Grafted Tumors in Mice. Nutr. Cancer 2004, 48, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, R.D.; Wilson, G.N.; Hajra, A. Oral Ether Lipid Therapy in Patients with Peroxisomal Disorders. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1987, 10, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fujino, T.; Yamada, T.; Asada, T.; Tsuboi, Y.; Wakana, C.; Mawatari, S.; Kono, S. Efficacy and Blood Plasmalogen Changes by Oral Administration of Plasmalogen in Patients with Mild Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. EBioMedicine 2017, 17, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Watanabe, H.; Okawara, M.; Matahira, Y.; Mano, T.; Wada, T.; Suzuki, N.; Takara, T. The Impact of Ascidian (Halocynthia Roretzi)-Derived Plasmalogen on Cognitive Function in Healthy Humans: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Oleo Sci. 2020, 69, 1597–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeba, R.; Hara, H.; Ishikawa, H.; Hayashi, S.; Yoshimura, N.; Kusano, J.; Takeoka, Y.; Yasuda, D.; Okazaki, T.; Kinoshita, M.; et al. Myo-Inositol Treatment Increases Serum Plasmalogens and Decreases Small Dense LDL, Particularly in Hyperlipidemic Subjects with Metabolic Syndrome. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2008, 54, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoffman-Kuczynski, B.; Reo, N. v Administration of Myo-Inositol Plus Ethanolamine Elevates Phosphatidylethanolamine Plasmalogen in the Rat Cerebellum. Neurochem. Res. 2005, 30, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczynski, B.; Reo, N.V. Evidence That Plasmalogen Is Protective Against Oxidative Stress in the Rat Brain. Neurochem. Res. 2006, 31, 639–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourque, M.; Grégoire, L.; di Paolo, T. The Plasmalogen Precursor Analog PPI-1011 Reduces the Development of L-DOPA-Induced Dyskinesias in de Novo MPTP Monkeys. Behav. Brain Res. 2017, 337, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Shi, H.-H.; Wang, C.-C.; Jiang, X.-M.; Xue, C.-H.; Yanagita, T.; Zhang, T.-T.; Wang, Y.-M. Eicosapentaenoic Acid-Enriched Phosphoethanolamine Plasmalogens Alleviated Atherosclerosis by Remodeling Gut Microbiota to Regulate Bile Acid Metabolism in LDLR−/− Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 5339–5348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, S.; Ramalho, M.J.; Pereira, M.d.C.; Loureiro, J.A. Resveratrol Brain Delivery for Neurological Disorders Prevention and Treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bozelli, J.C., Jr.; Epand, R.M. Plasmalogen Replacement Therapy. Membranes 2021, 11, 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes11110838

Bozelli JC Jr., Epand RM. Plasmalogen Replacement Therapy. Membranes. 2021; 11(11):838. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes11110838

Chicago/Turabian StyleBozelli, José Carlos, Jr., and Richard M. Epand. 2021. "Plasmalogen Replacement Therapy" Membranes 11, no. 11: 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes11110838

APA StyleBozelli, J. C., Jr., & Epand, R. M. (2021). Plasmalogen Replacement Therapy. Membranes, 11(11), 838. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes11110838