Characterisation of Cell-Mediated Immunity Against Bovine Alphaherpesvirus 1 (BoAHV-1) in Calves

Abstract

1. Introduction

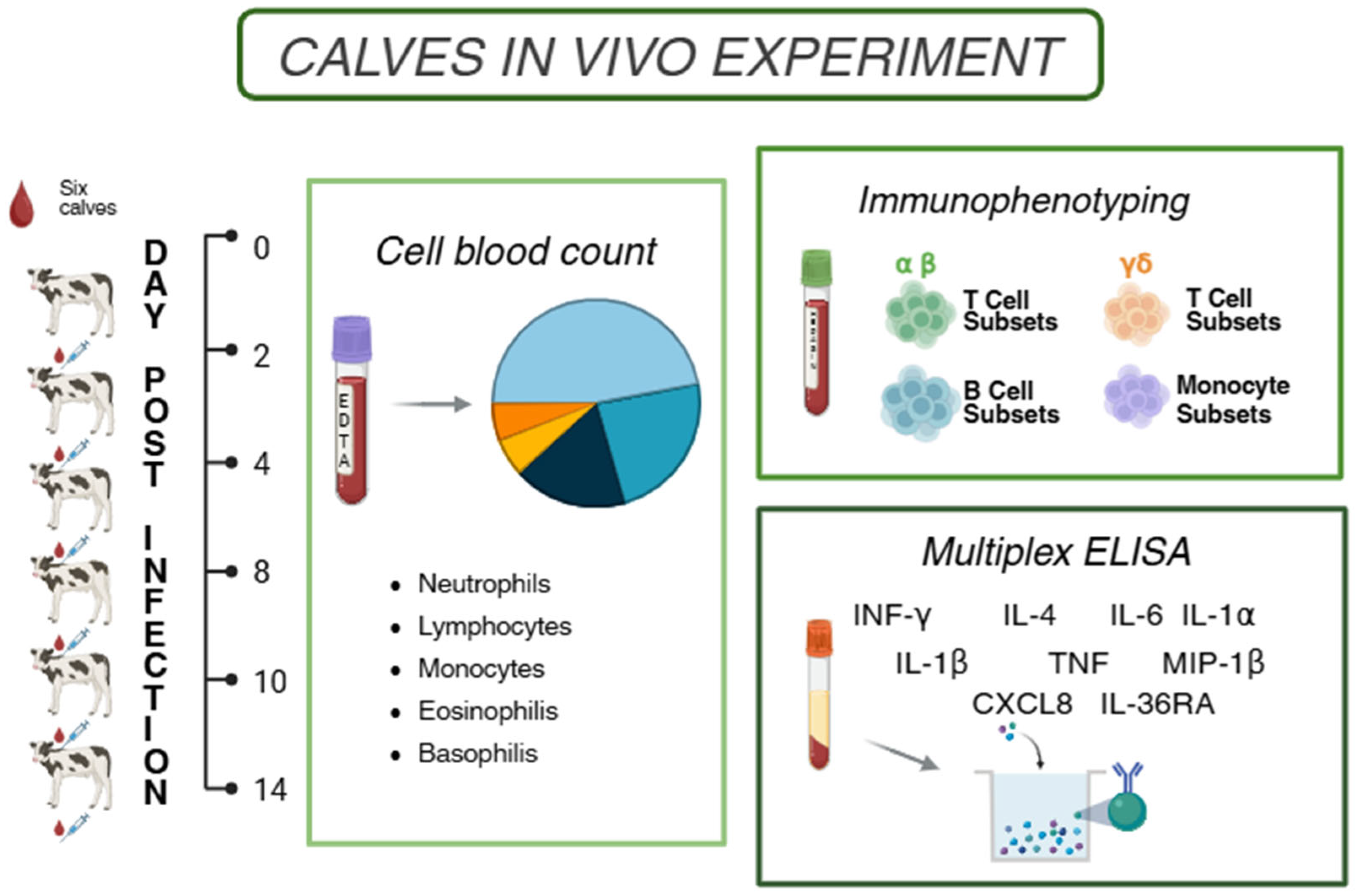

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

2.2. Animal Experiments

2.3. Collection of Blood Samples

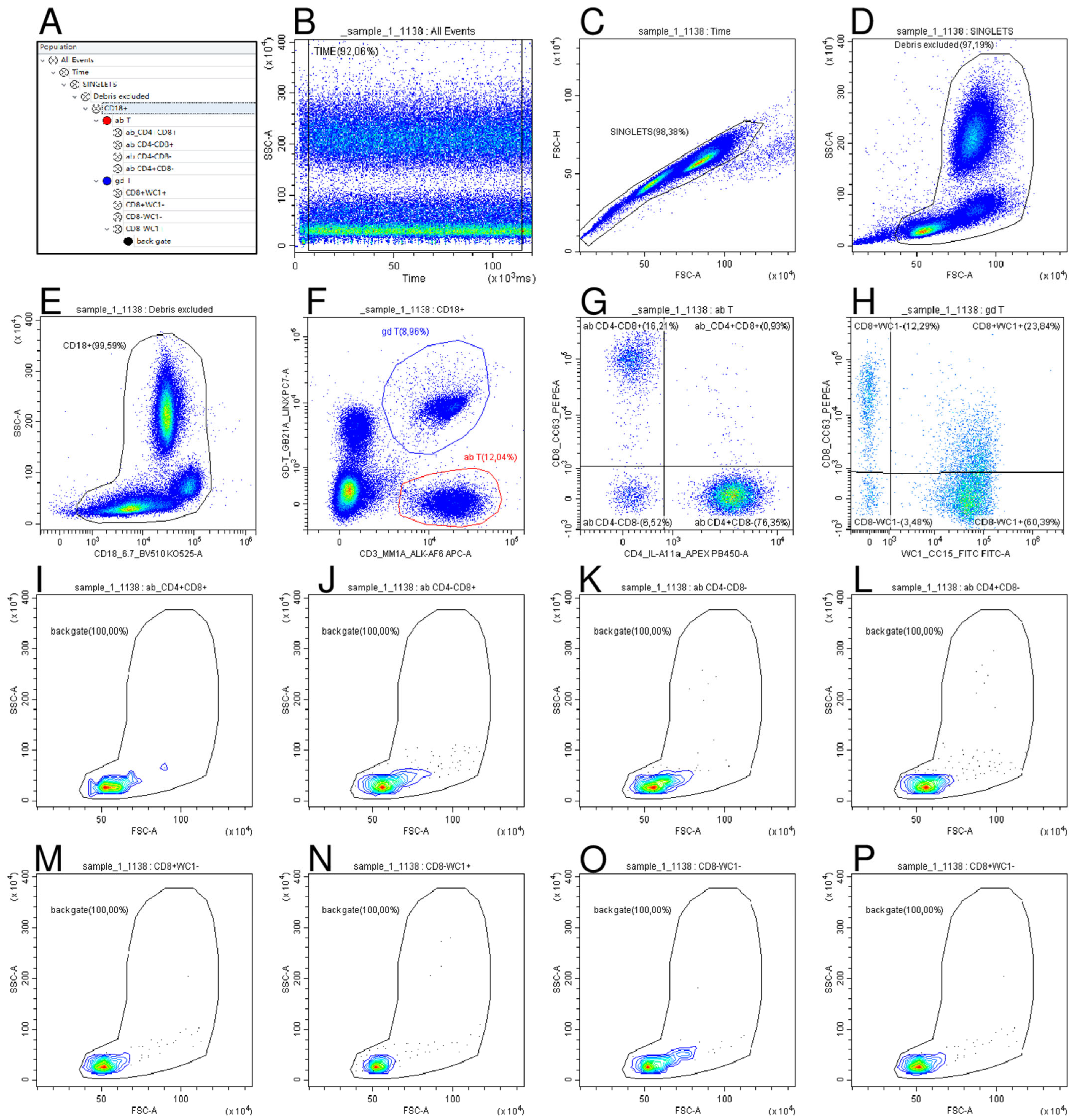

2.4. Haematological and Flow Cytometry Analysis

2.5. Evaluation of Serum Cytokines Levels

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

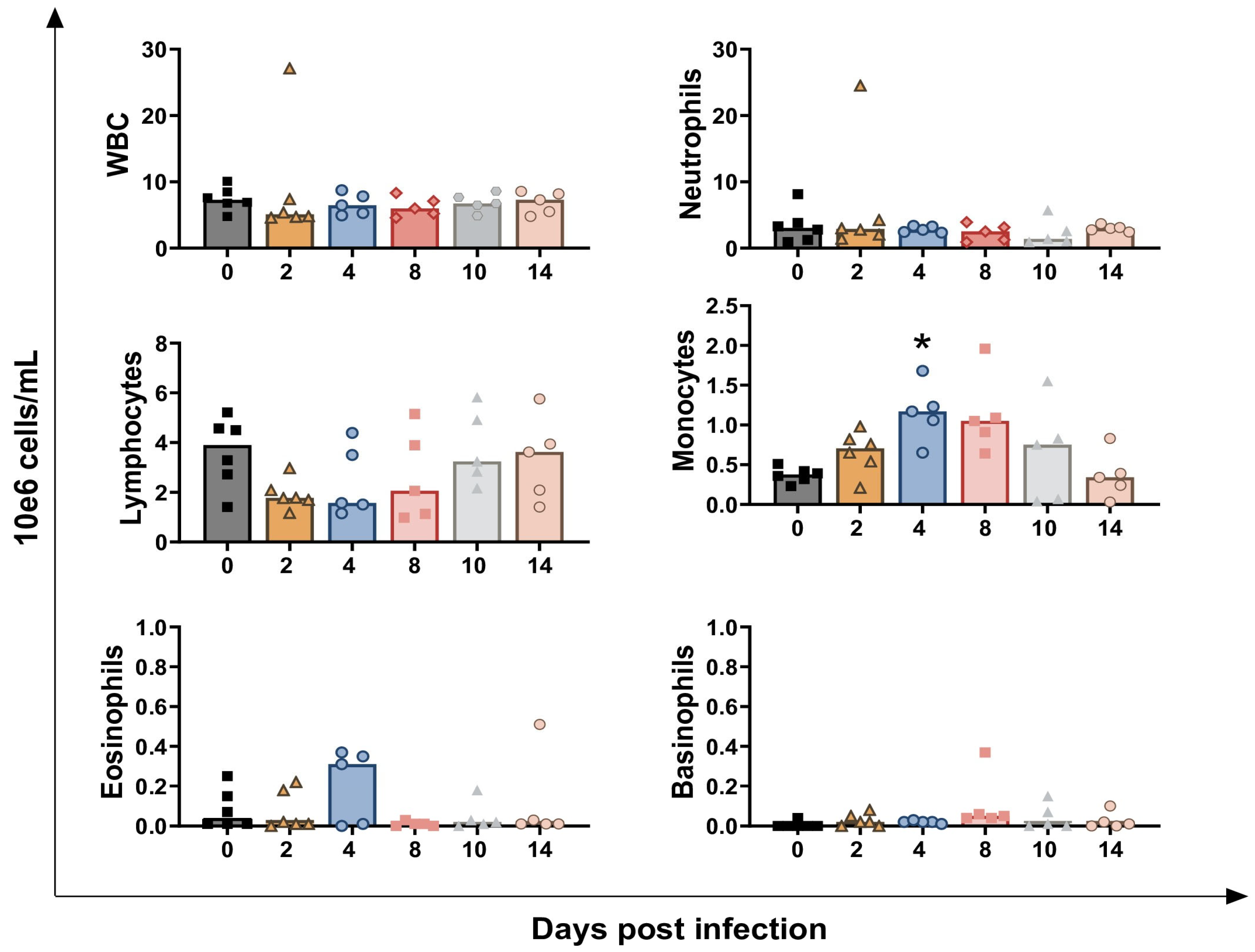

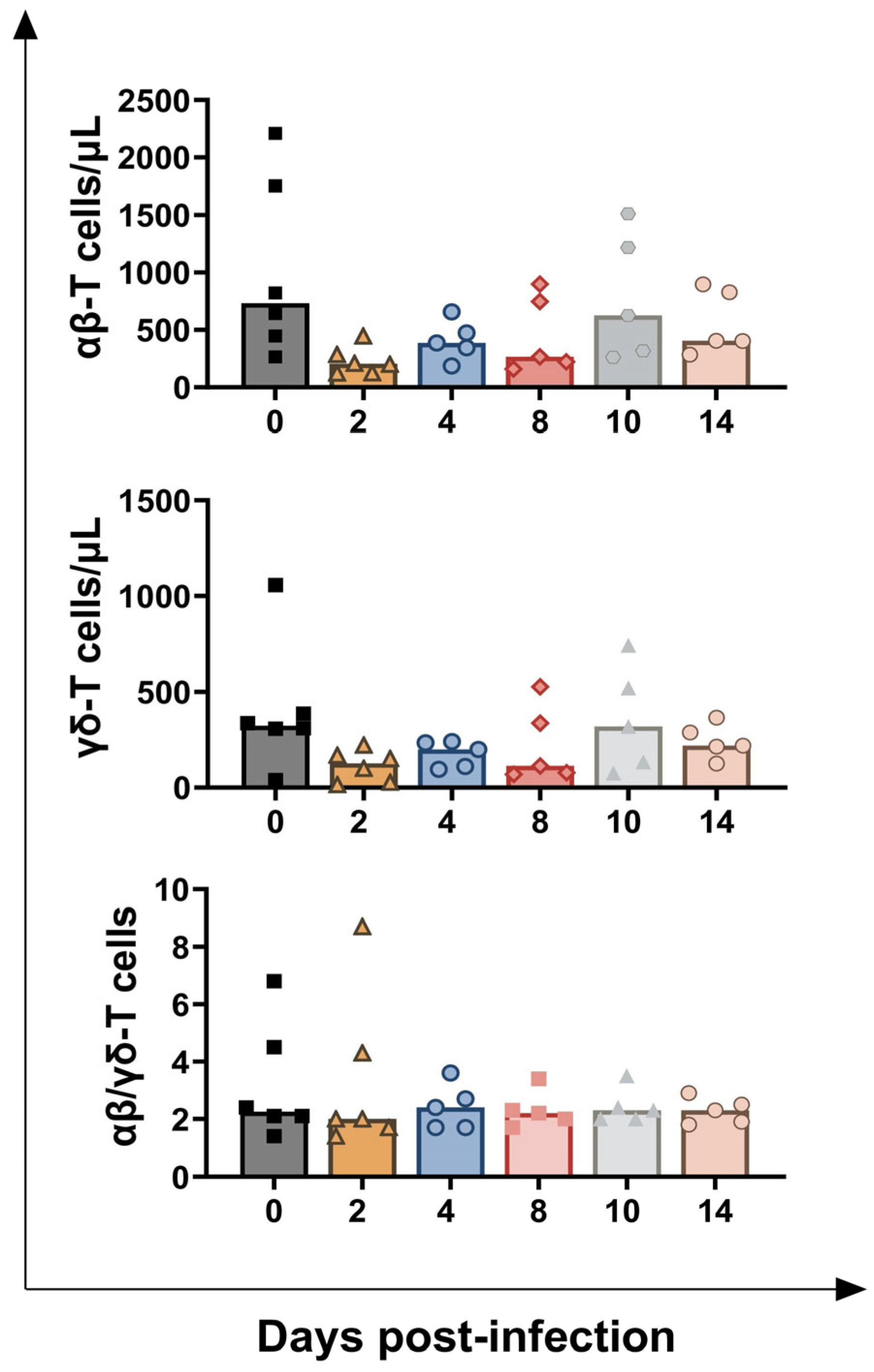

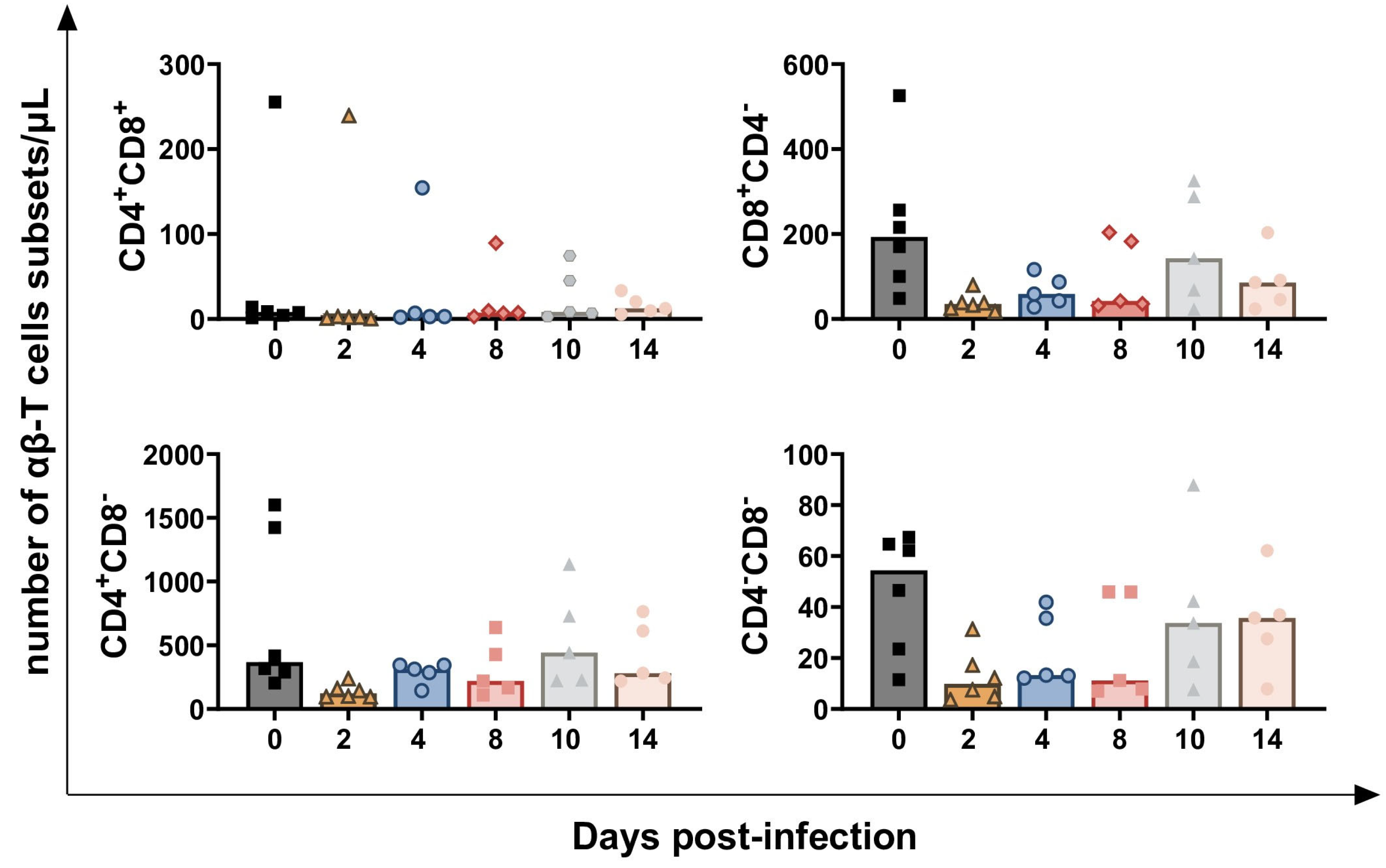

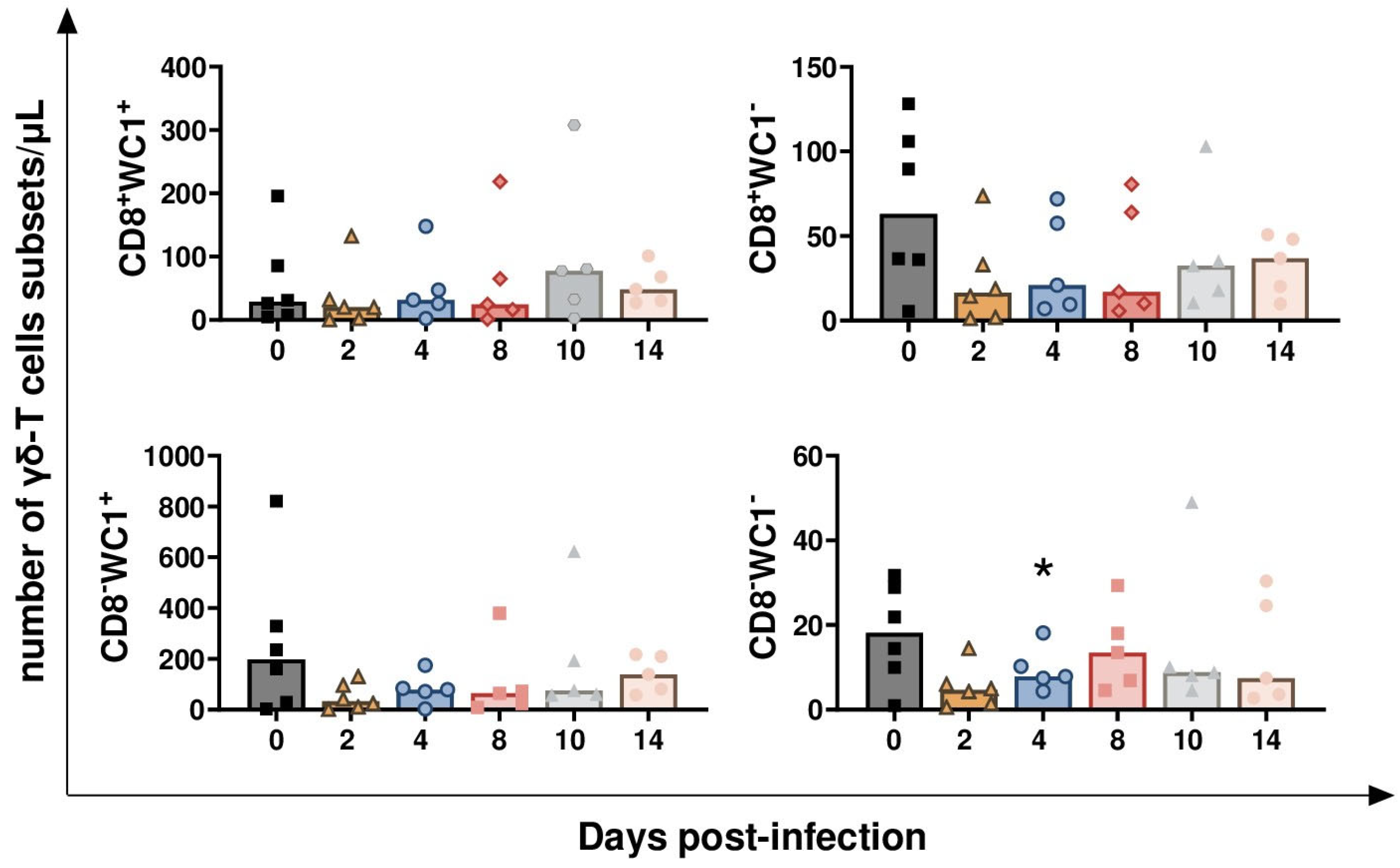

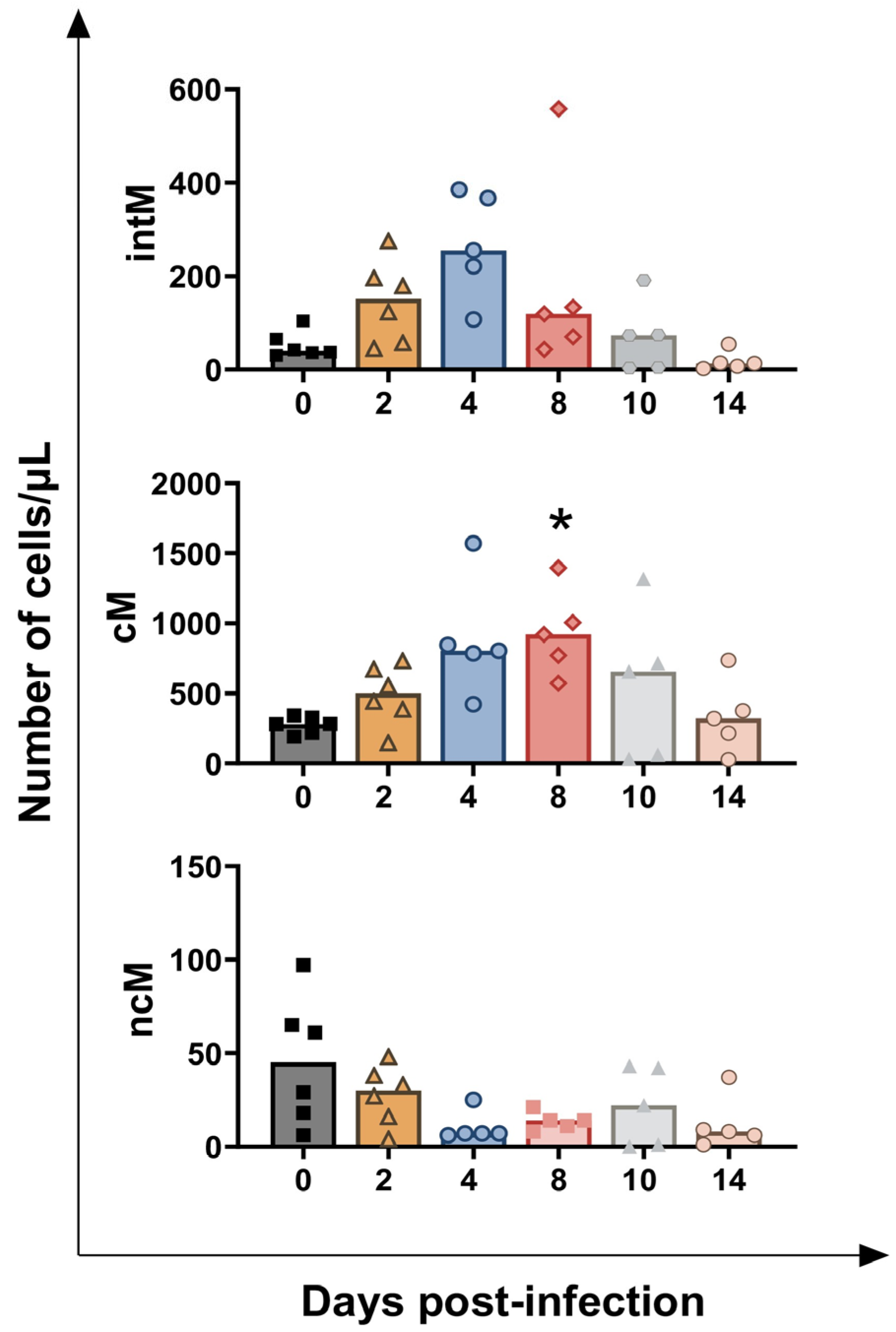

3.1. Impact of BoAHV-1 on Circulating Leukocytes Subsets

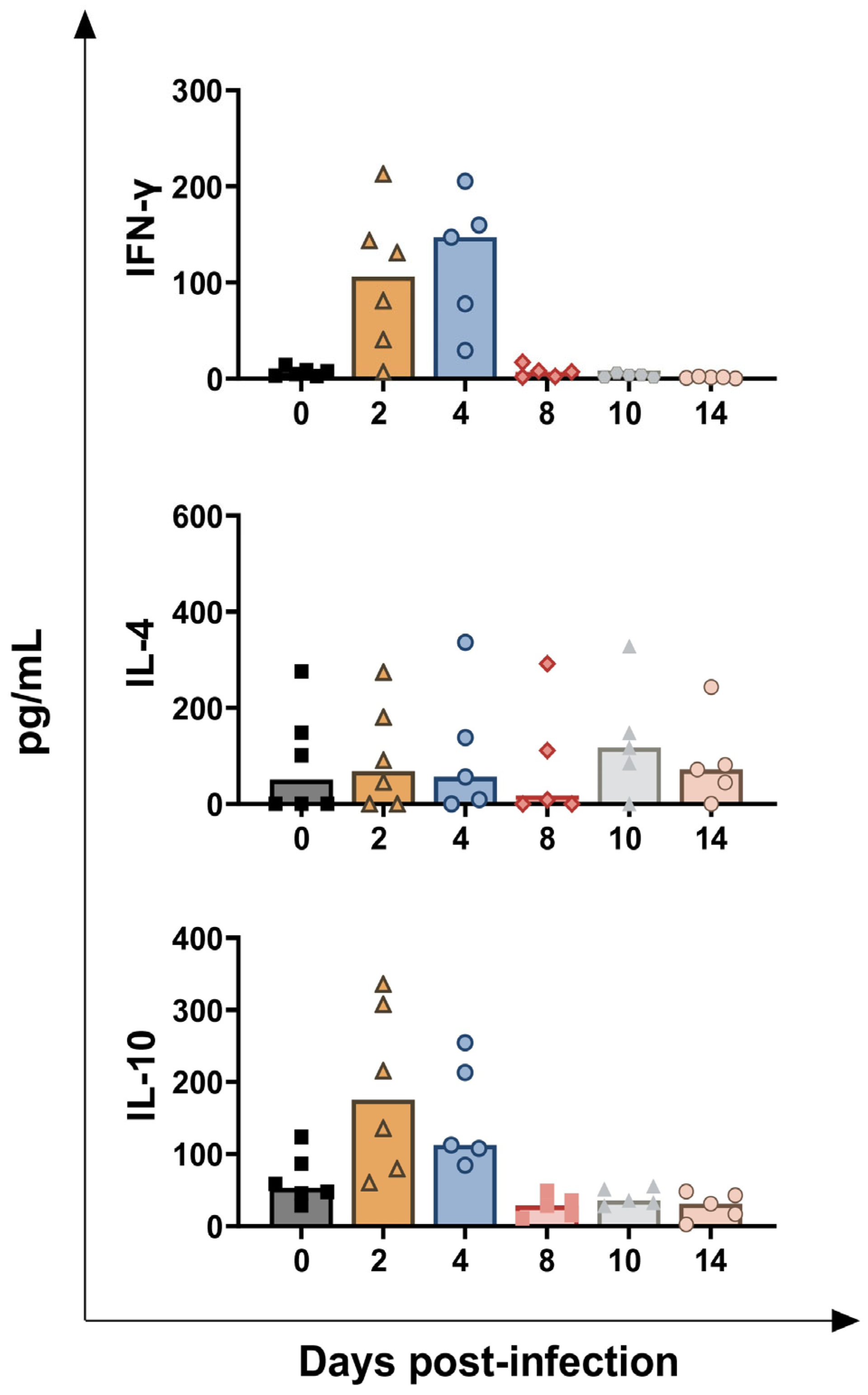

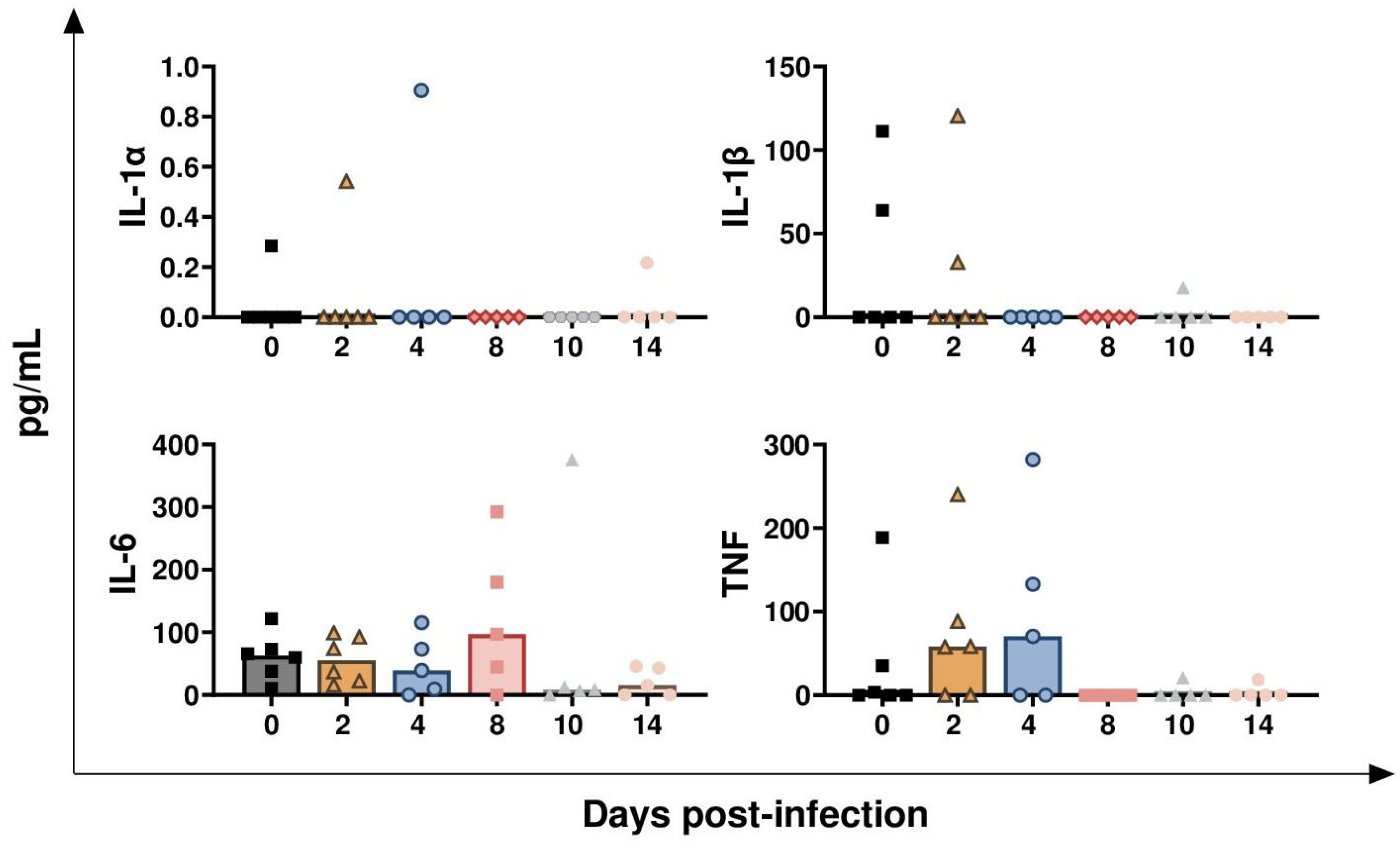

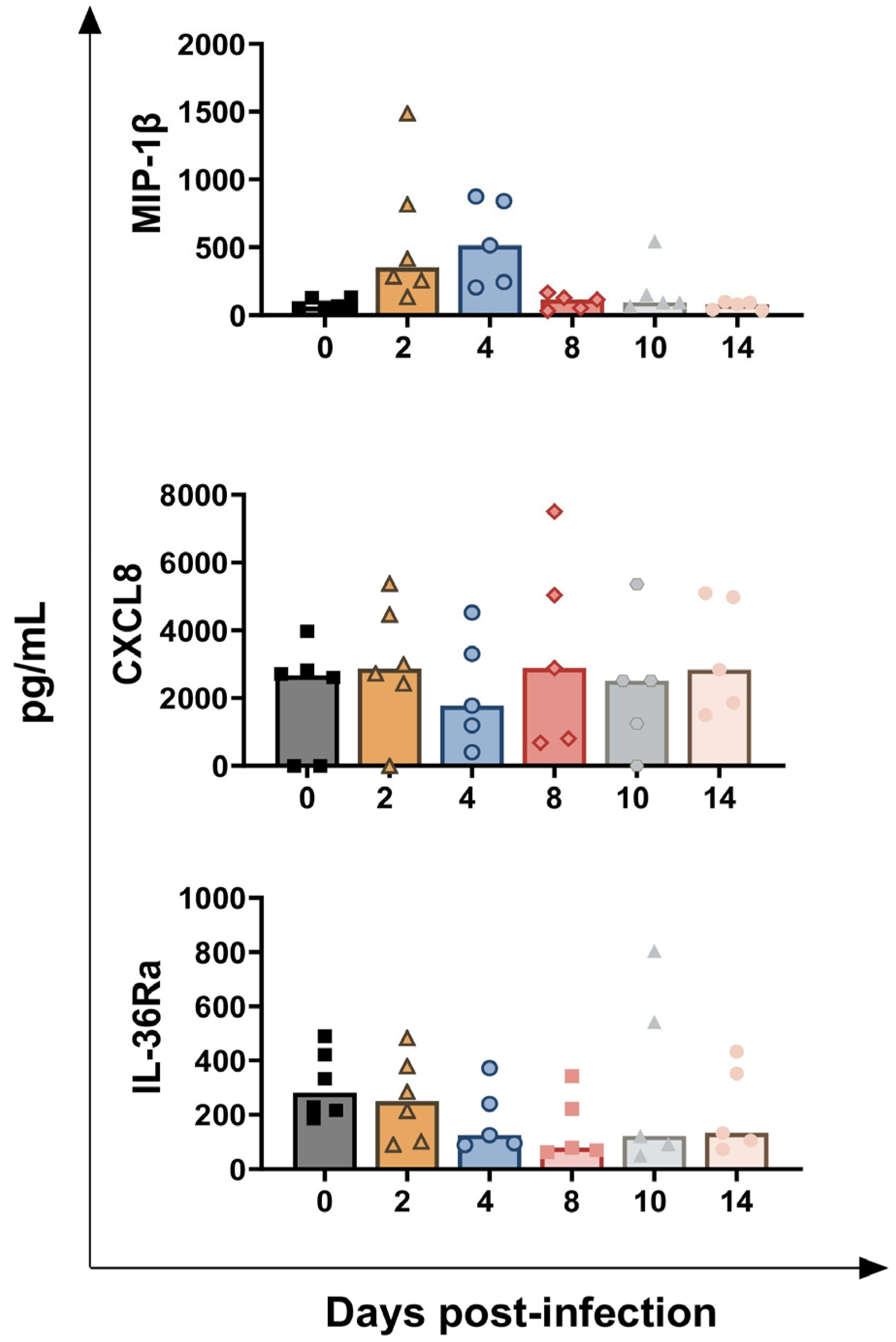

3.2. Impact of BoAHV-1 on Serum Cytokines Levels

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Virus Taxonomy. Available online: https://ictv.global/taxonomy/taxondetails?taxnode_id=202401440&taxon_name=Varicellovirus%20bovinealpha1 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Nandi, S.; Kumar, M.; Manohar, M.; Chauhan, S. Bovine herpes virus infections in cattle. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2009, 10, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, D.A. Bovine herpes virus-1 (BoHV-1) in cattle-a review with emphasis on reproductive impacts and the emergence of infection in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Ir. Vet. J. 2013, 66, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C. Bovine Herpesvirus 1 Counteracts Immune Responses and Immune-Surveillance to Enhance Pathogenesis and Virus Transmission. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrini, S.; Iscaro, C.; Righi, C. Antibody Responses to Bovine Alphaherpesvirus 1 (BoHV-1) in Passively Immunized Calves. Viruses 2019, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raaperi, K.; Orro, T.; Viltrop, A. Epidemiology and control of bovine herpesvirus 1 infection in Europe. Vet. J. 2014, 201, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrini, S.; Righi, C.; Costantino, G.; Scoccia, E.; Gobbi, P.; Pellegrini, C.; Pela, M.; Giammarioli, M.; Viola, G.; Sabato, R.; et al. Assessment of BoAHV-1 Seronegative Latent Carrier by the Administration of Two Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis Live Marker Vaccines in Calves. Vaccines 2024, 12, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiuk, L.; van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk, S.; Tikoo, S. Immunology of bovine herpesvirus 1 infection. Vet. Microbiol. 1996, 53, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, S.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Dimri, U.; Patra, P.H. Bovine herpesvirus-1 (BHV-1)—a re-emerging concern in livestock: A revisit to its biology, epidemiology, diagnosis, and prophylaxis. Vet. Q. 2013, 33, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righi, C.; Franzoni, G.; Feliziani, F.; Jones, C.; Petrini, S. The cell-mediated immune response against Bovine alphaherpesvirus 1 (BoHV-1) infection and vaccination. Vaccines 2023, 11, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risalde, M.A.; Molina, V.; Sánchez-Cordón, P.J.; Pedrera, M.; Panadero, R.; Romero-Palomo, F.; Gómez-Villamandos, J.C. Response of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in calves with subclinical bovine viral diarrhea challenged with bovine herpesvirus-1. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2011, 144, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Fu, S.; Deng, M.; Xie, Q.; Xu, H.; Liu, Z.; Hu, C.; Chen, H.; Guo, A. Attenuation of bovine herpesvirus type 1 by deletion of its glycoprotein G and tk genes and protection against virulent viral challenge. Vaccine 2011, 29, 8943–8950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, F.; Sylte, M.J.; O’Brien, S.; Schultz, R.; Peek, S.; van Reeth, K.; Czuprynski, C.J. Effect of experimental infection of cattle with bovine herpesvirus-1 (BHV-1) on the ex vivo interaction of bovine leukocytes with Mannheimia (Pasteurella) haemolytica leukotoxin. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2002, 84, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandoni, F.; Martucciello, A.; Petrini, S.; Steri, R.; Donniacuo, A.; Casciari, C.; Scatà, M.C.; Grassi, C.; Vecchio, D.; Feliziani, F.; et al. Assessment of Multicolor Flow Cytometry Panels to Study Leukocyte Subset Alterations in Water Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) During BVDV Acute Infection. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 574434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levings, R.L.; Roth, J.A. Immunity to bovine herpesvirus 1: I. Viral lifecycle and innate immunity. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2013, 14, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levings, R.L.; Roth, J.A. Immunity to bovine herpesvirus 1: II. Adaptative immunity and vaccinology. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2013, 14, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burucúa, M.M.; Quintana, S.; Lendez, P.; Cobo, E.R.; Ceriani, M.C.; Dolcini, G.; Odeón, A.C.; Pérez, S.E.; Marin, M.S. Modulation of cathelicidins, IFNβ and TNFα by bovine alpha-herpesviruses is dependent on the stage of the infectious cycle. Mol. Immunol. 2019, 111, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrini, S.; Martucciello, A.; Righi, C.; Cappelli, G.; Costantino, G.; Grassi, C.; Casciari, C.; Scoccia, E.; Tinelli, E.; Galiero, G.; et al. Evaluation of passive immunity from dams previously immunized with an inactivated glycoprotein E-deleted infectious bovine rhinotracheitis marker vaccine after challenge infection with wild-type bovine alphaherpesvirus 1 in calves. Vaccine X 2025, 25, 100670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandoni, F.; Fraboni, D.; Canonico, B.; Papa, S.; Buccisano, F.; Schuberth, H.J.; Hussen, J. Flow Cytometric Identification and Enumeration of Monocyte Subsets in Bovine and Water Buffalo Peripheral Blood. Curr. Protoc. 2023, 3, e676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoni, G.; Signorelli, F.; Mazzone, P.; Donniacuo, A.; De Matteis, G.; Grandoni, F.; Schiavo, L.; Zinellu, S.; Dei Giudici, S.; Bezos, J.; et al. Cytokines as potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of Mycobacterium bovis infection in Mediterranean buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis). Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1512571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, M.T.C.; Doster, A.; Jones, C. Bovine Herpesvirus 1 Can Infect CD4+ T Lymphocytes and Induce Programmed Cell Death during Acute Infection of Cattle. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 8657–8668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griebel, P.J.; Ohmann, H.B.; Lawman, M.J.P.; Babiuk, L.A. The interaction between bovine herpesvirus type 1 and activated bovine T lymphocytes. J. Gen. Virol. 1990, 71, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanon, E.; Lambot, M.; Hoornaert, S.; Lyaku, J.; Pastoret, P.P. Bovine herpesvirus 1-induced apoptosis: Phenotypic characterization of susceptible peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Arch. Virol. 1998, 143, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, V.; Risalde, M.A.; Sánchez-Cordón, P.J.; Pedrera, M.; Romero-Palomo, F.; Luzzago, C.; Gómez-Villamandos, J.C. Effect of infection with BHV-1 on peripheral blood leukocytes and lymphocyte subpopulations in calves with subclinical BVD. Res. Vet. Sci. 2013, 95, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amadori, M.; Archetti, I.L.; Verardi, R.; Berneri, C. Role of a distinct population of bovine gamma delta T cells in the immune response to viral agents. Viral Immunol. 1995, 8, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risalde, M.A.; Molina, V.; Sánchez-Cordón, P.J.; Romero-Palomo, F.; Pedrera, M.; Gómez-Villamandos, J.C. Effects of PreinfectionWith Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus on Immune Cells From the Lungs of Calves Inoculated With Bovine Herpesvirus 1.1. Vet. Pathol. 2015, 52, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Palomo, F.; Risalde, M.A.; Gómez-Villamandos, J.C. Immunopathologic Changes in the Thymus of Calves Pre-infected with BVDV and Challenged with BHV-1. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2015, 64, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, J.C.; Baldwin, C.L. Bovine gamma delta T cells and the function of gamma delta T cell specific WC1 co-receptors. Cell Immunol. 2015, 296, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, C.L.; Damani-Yokota, P.; Yirsaw, A.; Loonie, K.; Teixeira, A.F.; Gillespie, A. Special features of γδ T cells in ruminants. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 134, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauvau, G.; Chorro, L.; Spaulding, E.; Soudja, S.M. Inflammatory monocyte effector mechanisms. Cell Immunol. 2014, 291, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussen, J.; Schuberth, H.J. Heterogeneity of Bovine Peripheral Blood Monocytes. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chu, D.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; George, J.; Young, H.A.; Liu, G. Cytokines: From Clinical Significance to Quantification. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, e2004433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmgaard, L. Induction and regulation of IFNs during viral infections. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2004, 24, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, K.; Hertzog, P.J.; Ravasi, T.; Hume, D.A. Interferon-gamma: An overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2004, 75, 163–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.I.; Wei, H.; Weiss, M.; Pannhorst, K.; Paulsen, D.B. A triple gene mutant of BoHV-1 administered intranasally is significantly more efficacious than a BoHV-1 glycoprotein E-deleted virus against a virulent BoHV-1 challenge. Vaccine 2014, 32, 4909–4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, R.; Gonzalez-Cano, P.; Brownlie, R.; Griebel, P.J. Induction of interferon and interferon-induced antiviral effector genes following a primary bovine herpesvirus-1 (BHV-1) respiratory infection. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 1831–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattrocchi, V.; Soria, I.; Langellotti, C.A.; Gnazzo, V.; Gammella, M.; Moore, D.P.; Zamorano, P.I. A DNA Vaccine Formulated with Chemical Adjuvant Provides Partial Protection against Bovine Herpes Virus Infection in Cattle. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolums, A.R.; Siger, L.; Johnson, S.; Gallo, G.; Conlon, J. Rapid onset of protection following vaccination of calves with multivalent vaccines containing modified-live or modified-live and killed BHV-1 is associated with virus-specific interferon gamma production. Vaccine 2003, 21, 1158–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrini, S.; Ramadori, G.; Corradi, A.; Borghetti, P.; Lombardi, G.; Villa, R.; Bottarelli, E.; Guercio, A.; Amici, A.; Ferrari, M. Evaluation of safety and efficacy of DNA vaccines against bovine herpesvirus-1 (BoHV-1) in calves. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 34, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risalde, M.A.; Molina, V.; Sánchez-Cordón, P.J.; Romero-Palomo, F.; Pedrera, M.; Garfia, B.; Gómez-Villamandos, J.C. Pathogenic mechanisms implicated in the intravascular coagulation in the lungs of BVDV-infected calves challenged with BHV-1. Vet. Res. 2013, 44, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comerford, I.; McColl, S.R. Mini-review series: Focus on chemokines. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2011, 89, 183–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beste, M.T.; Lomakina, E.B.; Hammer, D.A.; Waugh, R.E. Immobilized IL-8 Triggers phagocytosis and dynamic changes in membrane microtopology in human neutrophils. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 43, 2207–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menten, P.; Wuyts, A.; Van Damme, J. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2002, 13, 455–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosser, D.M.; Zhang, X. Interleukin-10: New perspectives on an old cytokine. Immunol. Rev. 2008, 226, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Panel | Antigen | Antibody Clone | Source | Conjugation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel 1 | CD3 | MM1A | WSU-MAC 1 | Alexa Fluor 647 2 |

| CD4 | IL-A11a | WSU-MAC | Pacific Blue 3 | |

| CD8 | CC63 | Bio-Rad Laboratories | PE | |

| CD18 | 6.7 | BD | BV510 | |

| δ chain | GB21A | WSU-MAC | PE-Cy7 2 | |

| WC1 | CC15 | Bio-Rad Laboratories | FITC | |

| Panel 2 | CD18 | 6.7 | BD | BV510 |

| CD21 | LT21 | Thermo-Fisher | PE | |

| CD79a | HM47 | BD | APC | |

| Panel 3 | CD14 | TÜK4 | Bio-Rad Laboratories | AF750 |

| CD16 | KD1 | Bio-Rad Laboratories | FITC | |

| CD18 | 6.7 | BD | BV510 | |

| CD163 | 2A10/11 | Bio-Rad Laboratories | PE | |

| CD172a | CC149 | Bio-Rad Laboratories | PE-Cy5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Franzoni, G.; Righi, C.; De Donato, I.; Cappelli, G.; De Matteis, G.; Scoccia, E.; Costantino, G.; Giaconi, E.; Zinellu, S.; Grassi, C.; et al. Characterisation of Cell-Mediated Immunity Against Bovine Alphaherpesvirus 1 (BoAHV-1) in Calves. Vaccines 2025, 13, 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13100996

Franzoni G, Righi C, De Donato I, Cappelli G, De Matteis G, Scoccia E, Costantino G, Giaconi E, Zinellu S, Grassi C, et al. Characterisation of Cell-Mediated Immunity Against Bovine Alphaherpesvirus 1 (BoAHV-1) in Calves. Vaccines. 2025; 13(10):996. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13100996

Chicago/Turabian StyleFranzoni, Giulia, Cecilia Righi, Immacolata De Donato, Giovanna Cappelli, Giovanna De Matteis, Eleonora Scoccia, Giulia Costantino, Emanuela Giaconi, Susanna Zinellu, Carlo Grassi, and et al. 2025. "Characterisation of Cell-Mediated Immunity Against Bovine Alphaherpesvirus 1 (BoAHV-1) in Calves" Vaccines 13, no. 10: 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13100996

APA StyleFranzoni, G., Righi, C., De Donato, I., Cappelli, G., De Matteis, G., Scoccia, E., Costantino, G., Giaconi, E., Zinellu, S., Grassi, C., Martucciello, A., Grandoni, F., & Petrini, S. (2025). Characterisation of Cell-Mediated Immunity Against Bovine Alphaherpesvirus 1 (BoAHV-1) in Calves. Vaccines, 13(10), 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13100996