1. Introduction

Seasonal influenza is a public health problem and a major source of direct and indirect costs arising from the case management and complications of the disease. Indeed, influenza viruses have a major epidemiological, social, and economic impact on industrialised countries [

1,

2,

3]. Currently, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the number of influenza-related deaths worldwide ranges from 250,000 to 650,000, while according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), between 4 and 50 million people contract symptomatic influenza in Europe every year, resulting in 15,000 to 70,000 deaths [

1,

4,

5,

6]. In Italy alone, 5 to 8 million people are affected every year, with a case fatality rate of 8000 deaths/year [

6,

7,

8]. Ninety percent of deaths occur in subjects over 65 years of age, in particular among those with co-morbidities [

7].

The most effective preventive strategy available to reduce the burden of the disease is vaccination [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Adherence to flu vaccination is especially important in the current pandemic, as the initial symptoms of COVID-19 are very similar to those of influenza and, therefore, the concomitance of seasonal influenza and SARS-CoV-2 infection would place an additional burden on the health service, with increasing difficulties for physicians to reach diagnosis [

13,

14]. In this regard, the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) of the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends offering influenza vaccination with priority given to healthcare workers, adults ≥ 65 years, pregnant women, individuals with underlying health conditions, and children aged 6–59 months [

11,

12,

13]. In Italy, the same priority groups are recommended yearly by the Ministry of Health and the Regions [

15].

Among the indicated cohorts, healthcare workers (HCWs) are particularly at risk of contracting influenza (clinical and subclinical) and of transmitting the infection to patients whose underlying conditions increase their risk of complications [

8,

16].

Several studies have investigated the causes of low compliance by healthcare professionals. These have found that the main determinants of hesitation are: (i) inadequate awareness campaigns; (ii) altered risk perception; (iii) insufficient health education on the efficacy of the influenza vaccine and/or possible adverse reactions; (iv) lack of access to vaccination facilities; (v) socio-demographic variables. In addition, several authors state that one of the main determinants of the low uptake of the flu vaccine for healthcare workers is a lack of time to attend the vaccination clinic [

8,

17,

18,

19,

20].

Among the policies recommended by international public health organisations to improve vaccination coverage among healthcare workers, the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cites on-site influenza vaccination as a proven and cost-effective strategy that increases productivity, reduces sick leave, and improves vaccination adherence among HCWs [

21,

22,

23].

Bearing in mind the importance of flu vaccination for HCWs and aiming to boost adherence, in Italy, the regulation of vaccination for this category is further provided for by Legislative Decree 9 April 2008 no. 81. This decree recommends actively offering the anti-influenza vaccine to HCWs annually during the flu season, from October to December [

15,

24,

25]. Nevertheless, flu vaccination coverage among HCWs remains low, as it is in other countries [

7,

8,

17,

26].

Based on these premises, the present study aims to investigate influenza vaccination coverage among HCWs employed by an Italian University Hospital, comparing the effect of the on-site vaccination strategy with the results from previous flu seasons during which the classic delivery model (invitation to attend the vaccination clinic) was used.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

The present study did not require ethical approval for its observational design according to the Italian law (Gazzetta Ufficiale no. 76 dated 31 March 2008).

The vaccination campaign was aimed at employees (3044 employees as of 1 December 2020) of the University Hospital of Sassari, Italy (AOU-SS), of whom 2119 were female and 925 male).

The AOU-SS is the main hospital in the Italian region of Sardinia in terms of the number and diversity of its professional and technological resources, and carries out multi-specialist care, teaching, and research activities for the entire northern territory of Sardinia. The organisational structure of the hospital is set out in the company act (art. 3 paragraph 1 bis of Legislative Decree no. 502/92 and subsequent amendments), which identifies a total of 77 operational units. Based on the type of activity carried out, these units are grouped into macro-areas: 29 medical areas; 18 surgical areas; 30 services/other. Its professional personnel are numerically distributed as shown in

Table 1.

The mean age of the staff is 47.64 years with a standard deviation of ±10.80 and the most represented age group is 50–60 with 1013 HCWs, of which 733 are females and 280 are males (

Table 2). Distribution by macro-area, age group, and gender of AOU-SS HCWs is shown in

Table 3.

2.2. Project Planning

As regards the flu vaccination offer, until the 2018–2019 season AOU-SS guaranteed the provision of the vaccination service at a single dedicated vaccination clinic, which the HCWs voluntarily attended to receive the flu jab. This standard practice made flu vaccination available to staff between October of each year and January of the following year and made it possible to reach a vaccination coverage that fluctuated between 13% and 15% of the company population.

The flu vaccination campaign for the 2020–2021 season represents the final phase of a three-year vaccination communication project that included the 2018–2019, 2019–2020, and 2020–2021 seasons. This project involved the implementation of activities divided into 4 distinct phases as described in

Table 4.

2.2.1. Flu Vaccination Offer in the 2018–2019 and 2019–2020 Seasons

In particular, a cognitive survey of the company’s population was conducted during the 2018–2019 season.

In order to assess the attitudes, behaviours and knowledge of AOU-SS staff regarding influenza vaccination, an anonymous questionnaire was developed on the EUSurvey digital platform. The questionnaire was administered by sending a URL code via email to employees in the period between November 2018 and March 2019 [

8]. From the results of the survey, the authors describe difficulty in accessing vaccination as the main determinant of vaccination hesitation among HCWs.

In light of this variable, new vaccination delivery strategies were devised to be implemented in subsequent influenza seasons.

In addition to routine vaccination activities, these supply strategies included the implementation of a pilot flu vaccination programme administered directly on the ward (catch-up) by a team of specialists who vaccinated those HCWs who requested the vaccine via booking, on-site.

2.2.2. Flu Vaccination Offer in the 2020–2021 Season

The on-site vaccination strategy tested in the previous season was reproposed for the 2020–2021 season with a more articulated organisation structured around the needs of the operational units belonging to the medical, surgical, and service areas.

In particular, care departments with nursing activities (thus, able to self-administer the vaccine) were given the possibility of vaccinating staff directly in their own department, while for operational units and external companies who required medical or nursing staff to administer the jab, vaccination was offered at ad hoc vaccination clinics.

The mode of vaccine administration and venues implemented for the 2020–2021 influenza season are described in

Table 5.

The directors of each operational unit received a specific email explaining the vaccination strategies. The same information was also communicated on the AOU-SS website. In the weeks preceding the vaccination campaign, specific posters were displayed in each operational unit, and brochures on the subject of influenza and the importance of flu vaccination were distributed.

Specific forms were drawn up and sent to all the AOU-SS units and to all the managers of external services (maintenance companies, cleaning companies, etc.).

These forms included: (i) a dose request form; (ii) a medical history form to be filled in at the time of vaccination; (iii) an information sheet for the vaccinator and the vaccinee. After completion of these forms, they were then returned to the Hospital Hygiene and Infection Control Unit, which, in collaboration with the Medical Directorate Unit and depending on the availability of vaccines, arranged the scheduling of vaccination deliveries for self-vaccinating wards (with nursing and/or outpatient activities) and vaccination sessions for wards (without nursing and/or outpatient activities) which were unable to self-administer.

As confirmation of vaccination, a form was issued containing the vaccinee’s medical history, consent to vaccination and the batch of vaccine administered.

For each unit of vaccinated health personnel, the following variables were recorded: main demographic details, area of affiliation (medical/surgical/services), and professional category.

Data collection and informed consent were carried out by the staff of the Hospital Hygiene and Infection Control Unit.

For the 2020–2021 season, vaccinated HCWs received one dose of inactivated tetravalent split vaccine, administered intramuscularly into the deltoid; these individuals underwent a two-week follow-up to assess any adverse effects and subsequently reported to the pharmacovigilance system.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were entered on Excel (Microsoft Office, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and analysed using the STATA software 16 (StatCorp., Austin, TX, USA) and MedCalc (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium). Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and range, categorical variables as proportions. For the calculation of the vaccination coverage (VC%), the number of vaccinated health workers was used as a numerator and the number of employees of AOU-SS as of 31 December 2020 (in each OU) as denoter.

Differences among quantitative variables and frequencies were tested through the Student’s t-test and Χ2 test, respectively. Differences among proportions were tested with the z test. Linear trend in proportions was tested too. A two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed, and Odds Ratios were used to assess the relationship between the outcome (being vaccinated in 2020–2021) and the following variables related to personal and health workers’ characteristics: age, gender, profession, and area of activities. The outcome was established by attributing a value of 1 if the participant underwent vaccination, and a value of 0 otherwise. A two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

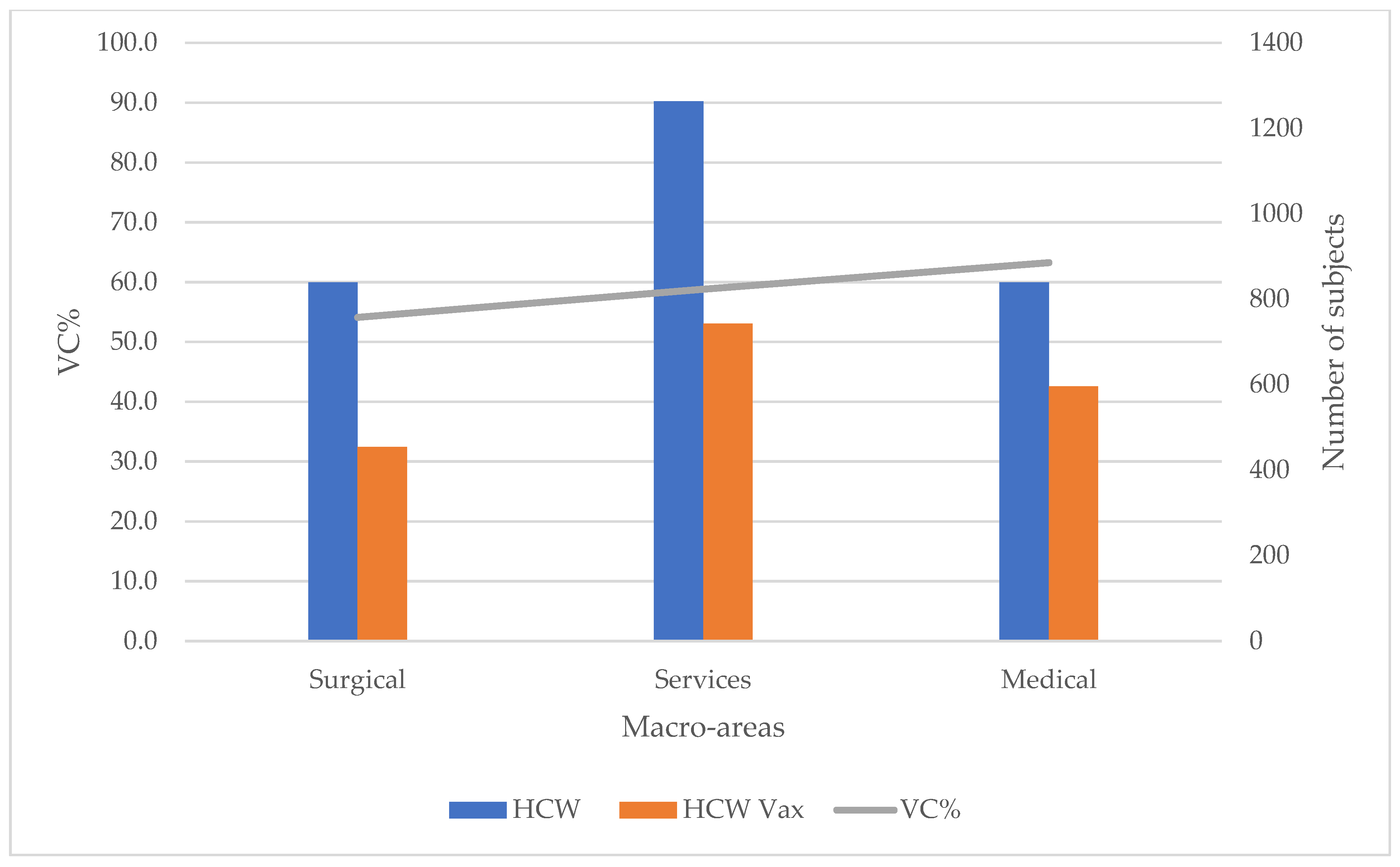

This study aimed to investigate the flu vaccination coverage of healthcare workers employed by AOU-SS as an indicator of compliance with this vaccination. The comparison of the coverage values recorded in the seasons 2018–2019 (VC% = 13.20%), 2019–2020 (VC% = 27.70%), and 2020–2021 (VC% = 58.90%) showed that in the last season under consideration (2020–2021) about 80% of HCWs preferred to be vaccinated in the workplace instead of using the standard method of vaccination provision (invitation to attend the vaccination clinic).

Although the vaccination coverage reached in the last year is still unsatisfactory compared to the national minimum values indicated by the Ministry of Health (VC% = 75%) [

15,

25], our study suggests that the on-site vaccination offer appears to be able to increase vaccination coverage and lead to an improvement in the compliance of health workers. In fact, the new vaccination strategies, which included both routine and on-site vaccination, made it possible to achieve more than three times the coverage values of previous seasons. This percentage was the highest in the years observed and, despite the absence of official statistics on the subject, it was higher than the vaccination coverage reported by the most recent national and European observations [

27,

28,

29,

30].

Furthermore, it is interesting to consider that the Ministerial Circular “Influenza prevention and control: recommendations for the 2020–2021 season” recommended bringing forward flu vaccination campaigns from the beginning of October 2020, offering vaccination to eligible individuals at any time during the season [

15]. This effectively extended the time available to AOU-SS to reach hospital employees, further influencing the increase in coverage.

Another fact worth bearing in mind is that, given the lengthy duration of the vaccination campaign, the vaccination coverage recorded at AOU-SS for the 2020–2021 season is to be considered as conservative and therefore the authors cannot provide information on the compliance of staff who did not undergo flu vaccination in the hospital. In fact, since vaccines were procured in different tranches over a period between October 2020 and January 2021, it was not possible to assess whether HCWs who were not immunised in the hospital were vaccinated by their general practitioner or if they purchased the vaccine from the pharmacy.

In addition, with regard to the characteristics of the personnel vaccinated in the hospital, our study reports that some professional categories, such as nurses and older HCWs, were less inclined to be vaccinated against influenza, while doctors (especially those in the medical area) were more compliant.

This is particularly important in the current pandemic in which the protection of a subgroup at high risk of contracting influenza, such as older HCWs, is particularly important: older nurses and doctors, who are therefore more experienced due to their professional expertise, are particularly valuable in healthcare emergencies [

31,

32,

33]. Therefore, flu vaccination takes on even greater importance as preventing the disease reduces not only the sequelae associated with it but also absence from work due to illness [

7,

8,

9,

10,

30,

33].

Our results confirm what has been observed by other authors who report low compliance with flu vaccination by older nurses in the surgical area [

8,

34,

35,

36]. This may be due to the fact that, in the past, the training of elderly HCWs (especially nurses) was mainly focused on the care of the patient rather than on the prevention of the disease, while in the present-day training of university students, great importance is given to prevention including prophylactic vaccination, with a consequent greater awareness of the issue.

Moreover, it is well known that influenza is often perceived by health professionals as an exaggerated or inapparent risk, compared to the actual incidence of the disease [

7,

8,

13,

37,

38,

39]. The altered perception of the health risk, in this context, has a significant impact on the decision to undergo vaccination and, as such, understanding the factors that influence the perceived risk becomes fundamental to be able to promote a true perception and encourage adequate adherence to preventive measures [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42].

This aspect had previously been highlighted in a survey carried out by the authors in the 2018–2019 season, in which useful indications emerged on the cognitive limits and misperception of the risks associated with influenza, aspects that, together with the declared difficulty of access to the vaccination service, strongly conditioned HCWs’ adherence to vaccination [

8]. In view of this, the three-year vaccination project implemented by the OU of Hospital Hygiene and Infection Control, using a strategy based on: (i) the ordinary supply of vaccinations (a single dedicated vaccination clinic) expanded with the setting up of two other vaccination clinics; (ii) vaccination on the ward with self-administration methods; (iii) health education interventions in the field, training, and information; (iv) a communication campaign structured on the needs of the target, has made it possible to achieve encouraging vaccination coverage values.

This gives cause for reflection on the importance of capillarisation of the vaccination offer as a tool to be used in the near future in order to reach HCWs more easily and increase vaccination compliance. Indeed, the on-site offer could be used not only for the administration of the vaccine in light of the staff’s working requirements but could also be a useful opportunity to educate HCWs on the significance of preventive prophylaxis and on the health risks for the individual and patients associated with influenza [

43]. This evidence is also confirmed in the literature by several studies describing the variables above as key determinants of vaccination compliance in HCWs [

8,

43,

44,

45].

Influenza vaccination among HCWs has been an intensely investigated topic in Italy in recent years, in particular with the aim to evaluate the campaigns’ effectiveness in increasing vaccination coverage [

45,

46,

47]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the effectiveness of these measures has become particularly important as the influenza vaccine is useful to distinguish between symptoms of influenza and those related to COVID-19 and enables the prevention of outbreaks in hospitals and disruption of health services due to HCWs requiring sick leave [

48,

49,

50]. Furthermore, co-circulation of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza virus during the 2020–2021 season may have caused an increased perception of the importance of flu vaccination among health professionals, leading to greater adherence to vaccination. In support of this interpretation of the survey results, numerous studies state that the perceived level of a health threat is a strong predictor of people’s intention to engage in preventative behaviours, including influenza vaccination [

39,

40,

45]. Therefore, the emergence of COVID-19, in relation to the flu vaccination campaign, may have a significant impact especially in the coming years, involving greater adherence to flu vaccination but also, should it be necessary to repeat vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 annually, timely planning of the two vaccination campaigns and more generally of the vaccination facilities in order to have sufficient and adequately trained personnel.

One important lesson learned from our three-year experience observing the behaviour of HCWs regarding adherence to influenza vaccination in multiple flu seasons is that increasing vaccination coverage among HCWs is not always guaranteed and is often a difficult goal to achieve. In fact, it depends on the synergy of numerous variables linked not only to the availability and provision of the vaccine but also to the presence of adequate and experienced human resources, health education and the promotion of well-structured communication campaigns [

8,

43,

44,

45,

51,

52,

53].

In this regard, the flu vaccination campaign promoted at AOU-SS through the use of different communication approaches may have had a positive influence on bringing healthcare personnel closer to the practice of vaccination. These activities included: posting explanatory leaflets and posters in each hospital ward, distributing information material, gaining the endorsement of the Provincial Command of the Fire Brigade who collaborated on the creation of a promotional advert, using social media, and conveying correct communication through websites dedicated to vaccination [

52].

In the future, therefore, it would be appropriate to repeat the on-site vaccination strategy, extending the offer to as many wards as possible and trying to involve mainly the professional groups who have the most contact with patients.

5. Conclusions

Healthcare professionals have a vital responsibility to their patients to ensure that those in need of medical care are assisted. However, vaccination coverage among health workers continues to be unsatisfactory and this data is also confirmed among health workers in the Italian hospital studied, in which the vaccination coverage recorded in recent years has always had values below 75%, albeit with some improvement.

It is therefore essential to continue to implement strategies to increase vaccination compliance and increase accountability to their patients, as required by national and international recommendations. For these reasons, there is an urgent need for studies aimed at implementing the best strategies to increase vaccination coverage in this cohort of professionals. This would also help policymakers and stakeholders to define specific initiatives and programmes in order to maximise the effects of flu vaccination programmes.

Further efforts are also needed to increase flu vaccination coverage rates among HCWs. This is a priority for public health and can be achieved through well-designed long-term intervention programmes that include a variety of coordinated management and organisational elements (e.g., vaccination offered in hospitals to staff and patients on discharge).