Who Is Willing to Get Vaccinated? A Study into the Psychological, Socio-Demographic, and Cultural Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

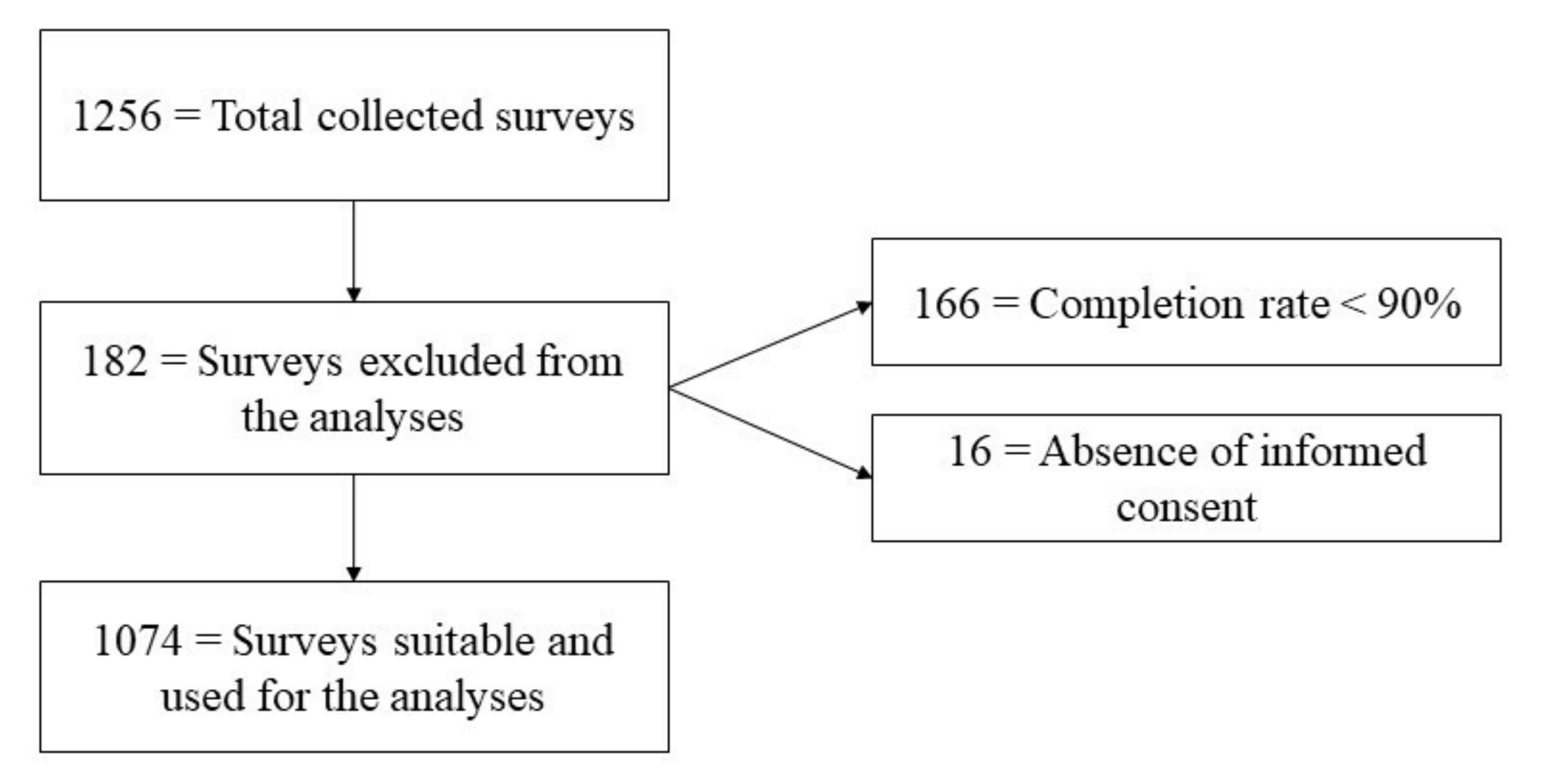

2.1. Sample

2.2. Survey

2.3. Symptoms of Anxiety Assessment: The 7-Item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7)

2.4. Health Locus of Control Assessment: The Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale (MHLCS)

2.5. Willingness to Get COVID-19 Vaccination Motivation: The Categorization Process

2.6. Willingness to Get COVID-19 Vaccination: Motivations

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Is There Anyone Responsible for the COVID-19 Pandemic?

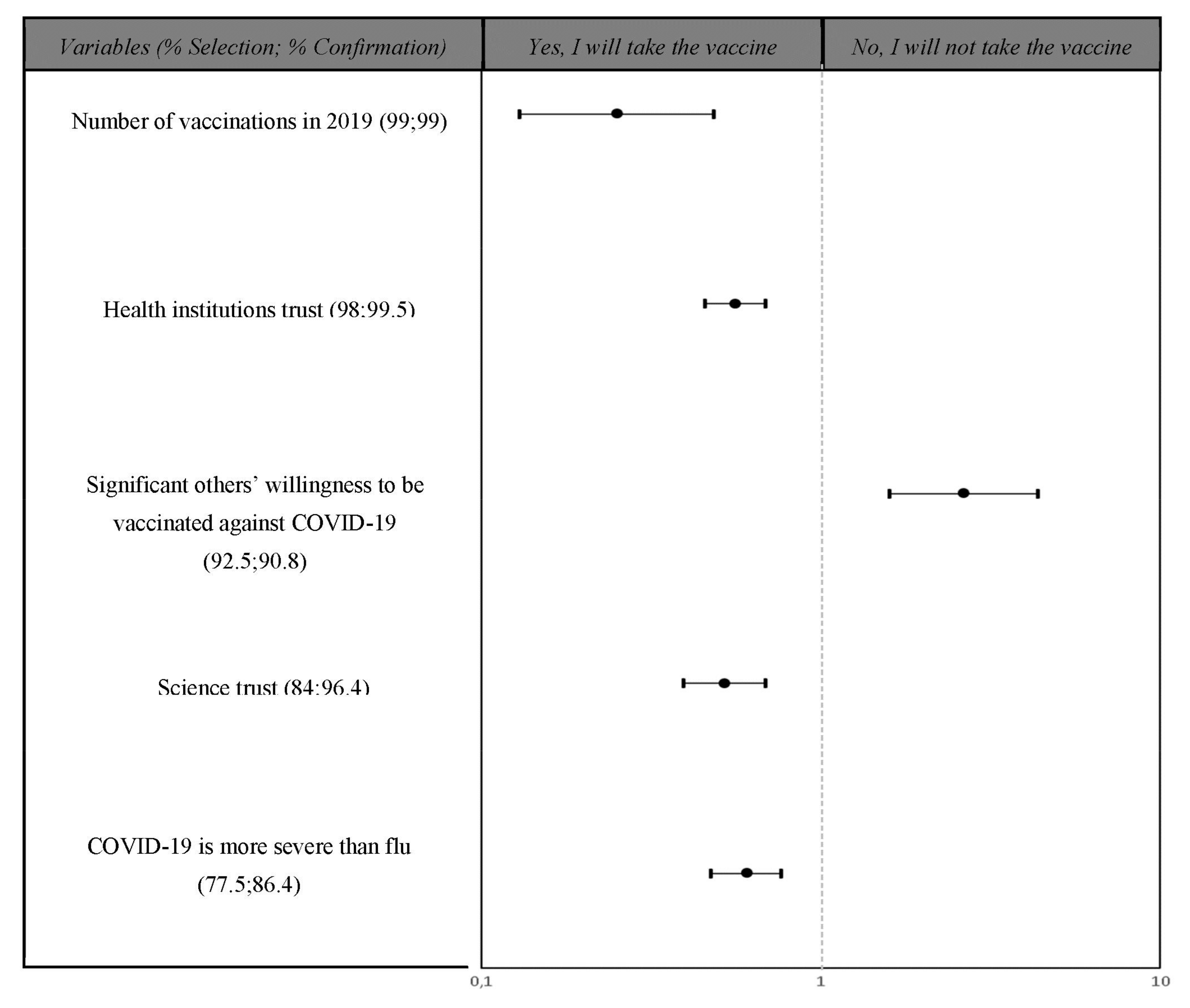

3.3. Cross-Validation Procedure

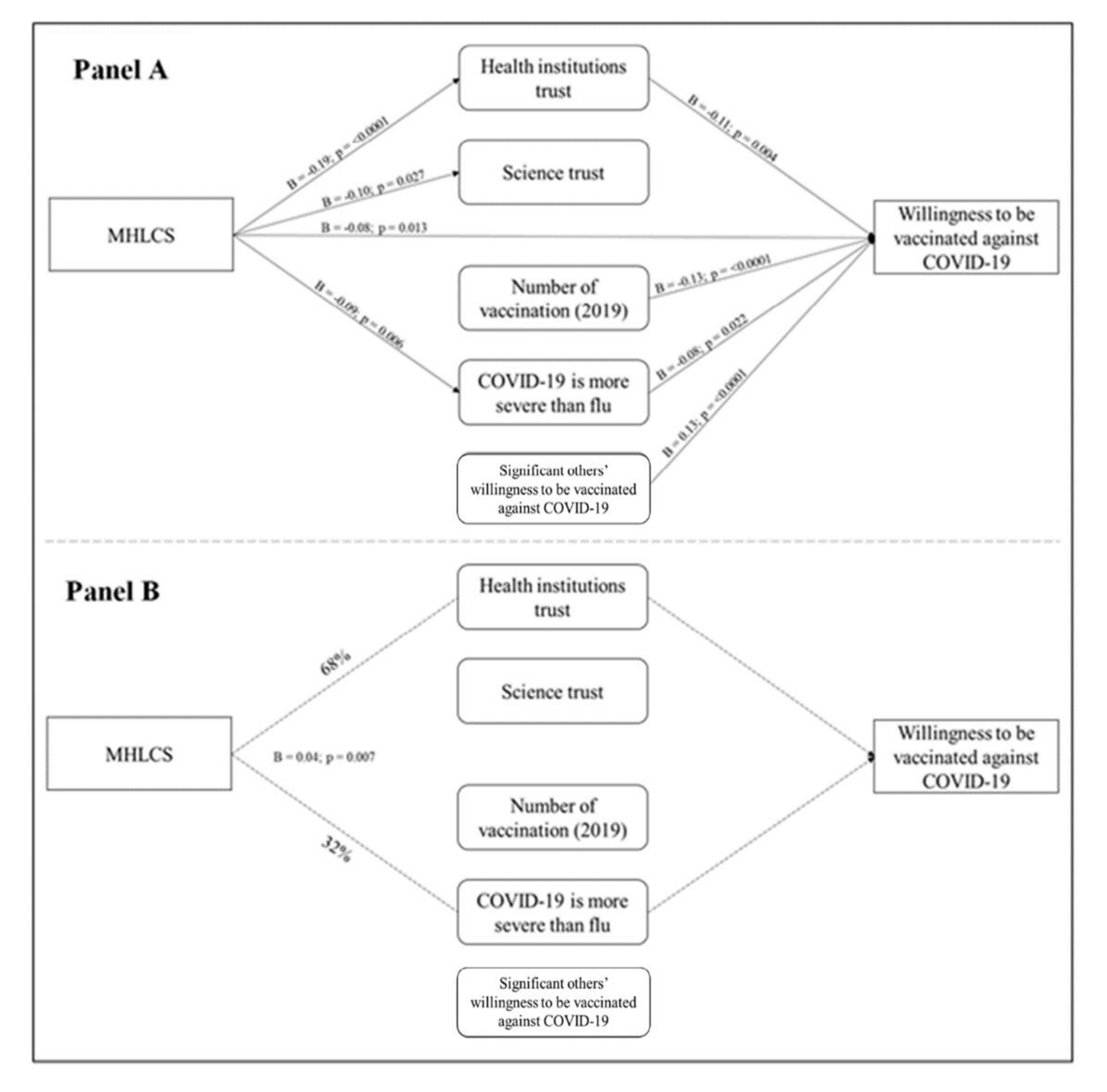

3.4. Path Analysis

3.4.1. Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale (MHLCS) (Chance Externality)

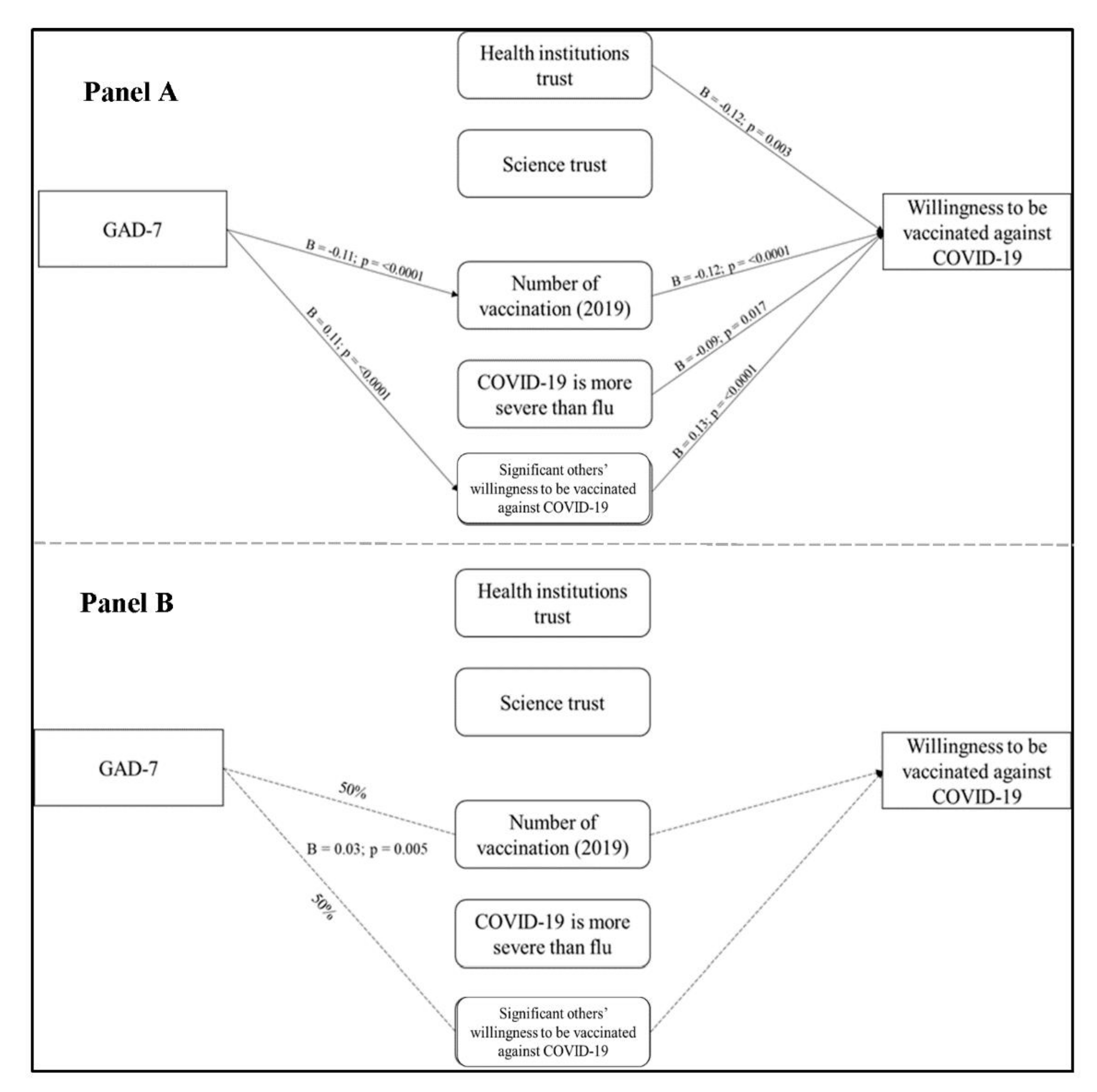

3.4.2. Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (Symptoms of Anxiety)

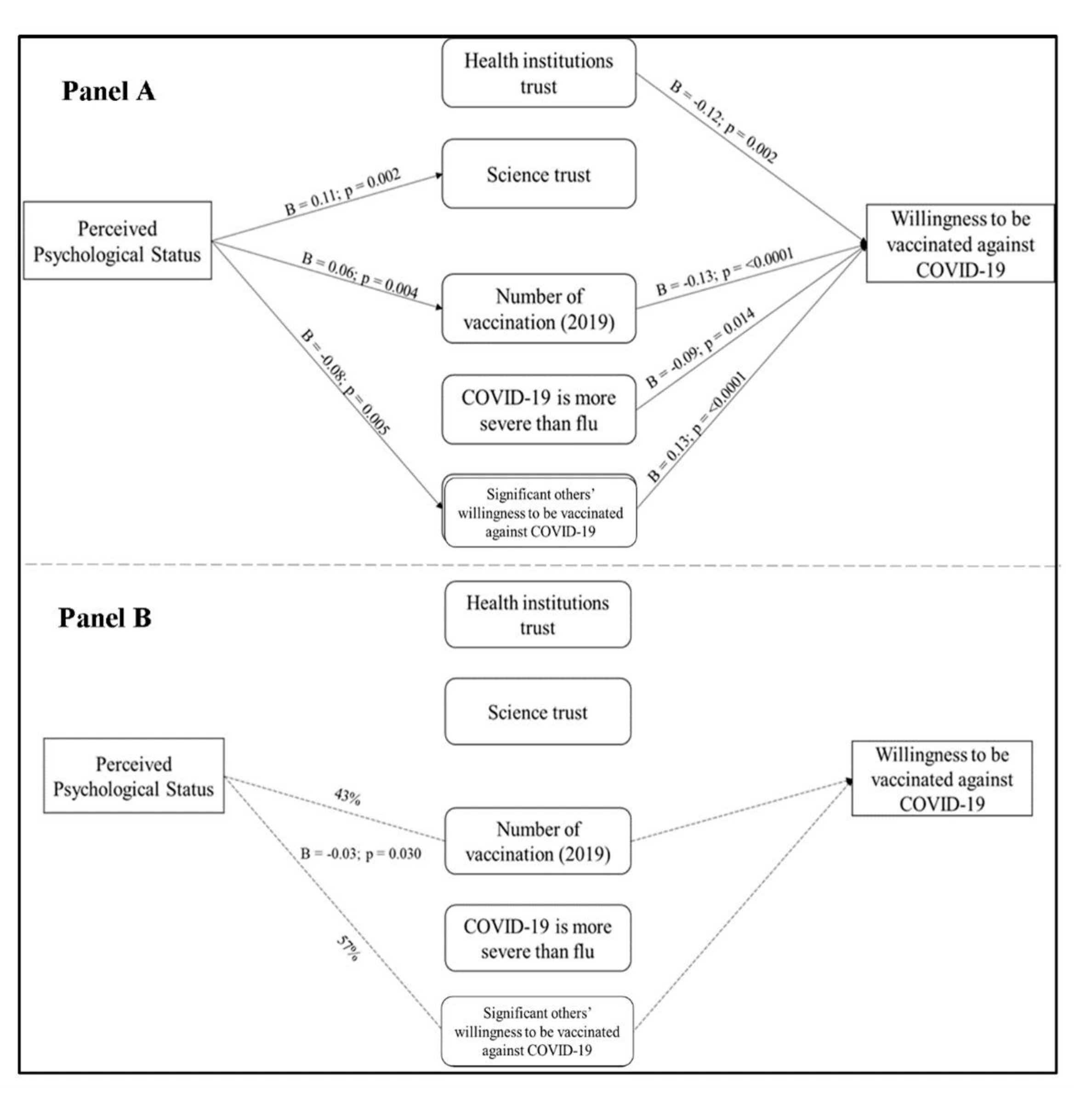

3.4.3. Perceived Psychological Status

4. Discussion

4.1. Self-Reported Reasons to Get the COVID-19 Vaccine

4.2. The Role of Beliefs about Human Responsibilities in the Pandemic

4.3. The Role of Psychological Variables on COVID-19 Vaccine-Related Decisions

4.4. Study Limitations

4.5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The COVID-19 Survey

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neitder Disagree Nor Agree | Agree | Strongly Agree | ||

| 1 | I am scared of contracting COVID-19 | |||||

| 2 | I am scared that my friends may contract COVID-19 | |||||

| 3 | I am scared that my family members may contract COVID-19 | |||||

| 4 | My health could be severely damaged if I contracted COVID-19 | |||||

| 5 | I think that to get COVID-19 in hospitals is more likely than in other places | |||||

| 6 | I think COVID-19 is more severe than the common flu | |||||

| 7 | I trust the Italian government and its directions to confront the pandemic | |||||

| 8 | I trust healthcare institutions (such as the WHO) and their directions to confront the pandemic | |||||

| 9 | I trust science and scientific research |

| Not at All | Several Days | More tdan Half tde Days | Nearly Every Day | ||

| 1 | Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge | ||||

| 2 | Not being able to stop or control worrying | ||||

| 3 | Worrying too much about different things | ||||

| 4 | Having trouble relaxing | ||||

| 5 | Being so restless that it is hard to sit still | ||||

| 6 | Becoming easily annoyed or irritable | ||||

| 7 | Feeling afraid as if something awful might happen |

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neitder Disagree Nor Agree | Agree | Strongly Agree | ||

| 1 | No matter what I do, if I am meant to get sick, I will get sick | |||||

| 2 | Most things that affect my health happen to me by accident | |||||

| 3 | Luck plays a big role in determining how soon I will recover from an illness | |||||

| 4 | My good health is largely a matter of good luck | |||||

| 5 | No matter what I do, I am likely to get sick | |||||

| 6 | I will stay healthy if that is meant to be so |

References

- Graham, B.S. Rapid COVID-19 vaccine development. Science 2020, 368, 945–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Erdos, G.; Huang, S.; Kenniston, T.W.; Balmert, S.; Carey, C.D.; Raj, V.S.; Epperly, M.W.; Klimstra, W.B.; Haagmans, B.L.; et al. Microneedle array delivered recombinant coronavirus vaccines: Immunogenicity and rapid translational development. EBioMedicine 2020, 55, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, B.; Hashimoto, K. Current status of potential therapeutic candidates for the COVID-19 crisis. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Lee, A.D.; Clemmons, N.S.; Redd, S.B.; Poser, S.; Blog, D.; Zucker, J.R.; Leung, J.; Link-Gelles, R.; Pham, H.; et al. National Update on Measles Cases and Outbreaks—United States, 1 January–1 October 2019. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 893–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotez, P.J. Texas and Its Measles Epidemics. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Ratzan, S.C.; Palayew, A.; Gostin, L.O.; Larson, H.J.; Rabin, K.; Kimball, S.; El-Mohandes, A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat. Med. 2020, 27, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jing, R.; Lai, X.; Zhang, H.; Lyu, Y.; Knoll, M.D.; Fang, H. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Vaccines 2020, 8, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K.A.; Bloomstone, S.J.; Walder, J.; Crawford, S.; Fouayzi, H.; Mazor, K.M. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: A survey of US adults. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; McFadden, S.M.; Elharake, J.; Omer, S.B. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 26, 100495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’souza, G.; Dowdy, D. What Is Herd Immunity and How Can We Achieve It with COVID-19? Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. 2020. Available online: https://www.jhsph.edu/covid-19/articles/achieving-herd-immunity-with-covid19.html (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Wang, H.; Li, T.; Barbarino, P.; Gauthier, S.; Brodaty, H.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Xie, H.; Sun, Y.; Yu, E.; Tang, Y.; et al. Dementia care during COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1190–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, A.A.; Eisenbach, N.; Taiber, S.; Morozov, N.G.; Mizrachi, M.; Zigron, A.; Srouji, S.; Sela, E. Vaccine hesitancy: The next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger, M.O. Triggering altruism increases the willingness to get vaccinated against COVID-19. Soc. Health Behav. 2020, 3, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Vallières, F.; Bentall, R.P.; Shevlin, M.; McBride, O.; Hartman, T.K.; McKay, R.; Bennett, K.; Mason, L.; Gibson-Miller, J.; et al. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, L.A. Snowball Sampling. Ann. Math. Stat. 1961, 32, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kertz, S.; Bigda-Peyton, J.; Bjorgvinsson, T. Validity of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 Scale in an Acute Psychiatric Sample. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2012, 20, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, L.A.; Brown, T.A. Psychometric Properties of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 (GAD-7) in Outpatients with Anxiety and Mood Disorders. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2017, 39, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B.; Decker, O.; Müller, S.; Brähler, E.; Schellberg, D.; Herzog, W.; Herzberg, P.Y. Validation and Standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the General Population. Med. Care 2008, 46, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazareth, M.; Richards, J.; Javalkar, K.; Haberman, C.; Zhong, Y.; Rak, E.; Jain, N.; de Ferris, M.E.D.-G.; Van Tilburg, M.A. Relating health locus of control to health care use, adherence, and transition readiness among youths with chronic conditions, north carolina, 2015. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2016, 13, E93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wallston, K.A.; Stein, M.J.; Smith, C. Form C of the MHLC Scales: A Condition-Specific Measure of Locus of Control. J. Pers. Assess. 1994, 63, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palamenghi, L.; Barello, S.; Boccia, S.; Graffigna, G. Mistrust in biomedical research and vaccine hesitancy: The forefront challenge in the battle against COVID-19 in Italy. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 785–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Rauber, D.; Betsch, C.; Lidolt, G.; Denker, M.-L. Barriers of Influenza Vaccination Intention and Behavior—A Systematic Review of Influenza Vaccine Hesitancy, 2005–2016. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diseases, T.L.I. The COVID-19 infodemic. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M.; Harris, E.A.; Fielding, K. The psychological roots of anti-vaccination attitudes: A 24-nation investigation. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salali, G.D.; Uysal, M.S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is associated with beliefs on the origin of the novel coronavirus in the UK and Turkey. Psychol. Med. 2020, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olagoke, A.A.; Olagoke, O.; Hughes, A.M. Intention to Vaccinate Against the Novel 2019 Coronavirus Disease: The Role of Health Locus of Control and Religiosity. J. Relig. Health 2021, 60, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Epel, O.; Levin-Zamir, D.; Cohen, V.; Elhayany, A. Internal locus of control, health literacy and health, an Israeli cultural perspective. Health Promot. Int. 2017, 34, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalakina-Paap, M.; Stephan, W.G.; Craig, T.; Gregory, W.L. Beliefs in Conspiracies. Political Psychol. 1999, 20, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Prooijen, J.-W.; Acker, M. The Influence of Control on Belief in Conspiracy Theories: Conceptual and Applied Extensions. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2015, 29, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Prooijen, J.-W. Empowerment as a Tool to Reduce Belief in Conspiracy Theories. In Conspiracy Theories and the People Who Believe Them; Oxford University Press (OUP): New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 432–442. [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein, C.R.; Vermeule, A. Symposium on conspiracy theories: Conspiracy theories: Causes and cures. J. Political Philos. 2009, 17, 202–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| When It Will Become Available to You, Will You Get the COVID-19 Vaccination? | Categories | Examples of the Given Answers | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, I will | Social/moral duty | It is a social duty to protect my community | 326 (28.3%) |

| Vaccine’s efficacy | It is the only effective way out of the emergency | 258 (22.4%) | |

| Desire to return to a “normal” (pre-pandemic) life | I want my life back | 127 (11.0%) | |

| Trust | I believe in science | 126 (10.9%) | |

| Self-protection | I do not want to get ill with COVID | 284 (27,5%) | |

| No, I will not | Questioning the vaccine efficacy | Apparently, you can catch COVID even if you have been vaccinated | 10 (19.6%) |

| Personal health issues | I have allergies that make this vaccine unsuitable for me | 7 (13.7%) | |

| Questioning the vaccine’s necessity | I am not at risk of getting COVID | 5 (9.8%) | |

| Generic no-vax opinions | I hate to enrich Big Pharma | 3 (5.9%) | |

| Questioning the vaccine’s safety | The vaccine has not been sufficiently tested; its long-term effects are still unknown | 22 (43.1%) | |

| Alternative remedies available | There are other natural ways to confront COVID-19, such as a healthy lifestyle | 4 (7.8%) | |

| I do not know | Questioning the vaccine’s efficacy | I am not sure about the COVID-19 vaccine efficacy | 14 (10.3%) |

| Personal health issues | I do not know weather the COVID-19 vaccine may worsen my health issues | 11 (8.1%) | |

| Questioning the vaccine’s necessity | I do not know if it is necessary for me | 7 (5.1%) | |

| Questioning the vaccine’s safety | I do not know if the vaccine is safe | 51 (37.5%) | |

| Alternative remedies available | I think that there are other remedies that maybe are useful to prevent COVID-19 infection | 4 (2.9%) | |

| COVID-19 previous infection | I have already contracted COVID-19 and I do not know if I will get the vaccination | 3 (2.2%) | |

| No specific reason | I do not know | 2 (1.5%) | |

| Waiting for medical advice | I will decide after consulting my doctor | 7 (5.1%) | |

| Not decided yet | I have not decided yet | 14 (10.3%) | |

| Insufficient/confusing information | I feel I do ot know enough about this vaccine; I have not received enough information yet | 23 (16.9%) |

| Collected Variables | No + I Do Not Know (n = 157; 14.6%) | Yes (n = 916; 85.4%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 45.04 ± 13.1 | 43.9 ± 15.27 | 0.3794 |

| Sex (men) | 37 (23.4) | 312 (34.1) | 0.0095 |

| Education | |||

| Primary school | 0 (0) | 2 (0.22) | 0.0006 |

| Secondary school | 10 (3.4) | 40 (4.4) | |

| High school | 70 (44.6) | 277 (30.2) | |

| University | 59 (37.6) | 379 (41.4) | |

| Post-university (e.g., PhD) | 18 (11.5) | 218 (23.8) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 16 (10.2) | 146 (15.9) | 0.1244 |

| In a relationship | 15 (9.5) | 126 (13.7) | |

| Married | 119 (75.8) | 601 (65.6) | |

| Separated/divorced | 6 (3.8) | 32 (3.5) | |

| Widowed | 1 (0.6) | 11 (1.2) | |

| Geographical origin | |||

| Northern Italy | 129 (82.2) | 784 (85.6) | 0.2521 |

| Center Italy | 8 (5.1) | 53 (5.8) | |

| South Italy | 20 (12.7) | 79 (8.6) | |

| Occupation (employed) | 117 (74.5) | 664 (72.5) | 0.597 |

| Sanitary job (yes) | 34 (21.7) | 315 (34.4) | 0.0017 |

| Perceived physical status | 3.87 ± 0.72 | 4 ± 0.65 | 0.0149 |

| Healthy participants (yes) | 113 (71.9) | 633 (69.1) | 0.4704 |

| Actual diseases number | 0.36 ± 0.59 | 0.40 ± 0.66 | 0.6160 |

| Perceived psychological status | 3.68 ± 0.83 | 3.82 ± 0.76 | 0.0367 |

| Anxiety problems | 39 (24.8) | 182 (19.9) | 0.1547 |

| Mood problems | 23 (14.7) | 125 (13.7) | 0.7362 |

| Eating problems | 11 (7.0) | 38 (4.2) | 0.1130 |

| Obsession and compulsion problems | 5 (3.2) | 14 (1.5) | 0.1460 |

| Relationship problems | 19 (12.1) | 103 (11.2) | 0.7545 |

| Psychological treatment (yes) | 75 (47.8) | 414 (45.2) | 0.5496 |

| Symptoms of anxiety (GAD-7) | 7 ± 5.23 | 6.13 ± 4.41 | 0.0998 |

| Health locus of control (MHLCS, chance externality) | 15.01 ± 4.68 | 13.21 ± 4.49 | <0.0001 |

| Perceived probability of contracting COVID-19 (self) | 4.73 ± 2.23 | 5.21 ± 2.01 | 0.0066 |

| Perceived fear of contracting COVID-19 (self) | 3.11 ± 1.14 | 3.44 ± 0.98 | 0.0006 |

| Perceived fear of contracting COVID-19 (friends) | 3.41 ± 1.07 | 3.75 ± 0.82 | 0.0004 |

| Perceived fear of contracting COVID-19 (family) | 3.94 ± 1.02 | 4.16 ± 0.86 | 0.0172 |

| Perceived probability of severe health damage due to COVID-19 | 3.25 ± 1.02 | 3.45 ± 0.97 | 0.0204 |

| Perceived probability of contracting COVID-19 if going to the hospital | 2.79 ± 1.08 | 2.41 ± 1.06 | <0.0001 |

| Belief that COVID-19 is more severe than the common flu | 3.9 ± 0.89 | 4.37 ± 0.71 | <0.0001 |

| Government trust | 2.68 ± 1.14 | 3.19 ± 0.99 | <0.0001 |

| Health institutions trust | 2.94 ± 1.06 | 3.78 ± 0.89 | <0.0001 |

| Science trust | 3.84 ± 0.87 | 4.48 ± 0.62 | <0.0001 |

| Significant others’ willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19 | 135(86.0) | 615 (67.1) | <0.0001 |

| Number of vaccinations received in 2019 | 0 (0;0) | 0 (0;1) | <0.0001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giuliani, M.; Ichino, A.; Bonomi, A.; Martoni, R.; Cammino, S.; Gorini, A. Who Is Willing to Get Vaccinated? A Study into the Psychological, Socio-Demographic, and Cultural Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions. Vaccines 2021, 9, 810. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9080810

Giuliani M, Ichino A, Bonomi A, Martoni R, Cammino S, Gorini A. Who Is Willing to Get Vaccinated? A Study into the Psychological, Socio-Demographic, and Cultural Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions. Vaccines. 2021; 9(8):810. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9080810

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiuliani, Mattia, Anna Ichino, Alice Bonomi, Riccardo Martoni, Stefania Cammino, and Alessandra Gorini. 2021. "Who Is Willing to Get Vaccinated? A Study into the Psychological, Socio-Demographic, and Cultural Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions" Vaccines 9, no. 8: 810. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9080810

APA StyleGiuliani, M., Ichino, A., Bonomi, A., Martoni, R., Cammino, S., & Gorini, A. (2021). Who Is Willing to Get Vaccinated? A Study into the Psychological, Socio-Demographic, and Cultural Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions. Vaccines, 9(8), 810. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9080810