Can Communication Strategies Combat COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy with Trade-Off between Public Service Messages and Public Skepticism? Experimental Evidence from Pakistan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. The Health Belief Model and Affect Theory

2.1.1. The Perceived Threat and Willingness to Take COVID-19 Vaccine

2.1.2. The Perceived Benefits and Willingness to Take COVID-19 Vaccine

2.1.3. The Self-Efficacy and Willingness to Take COVID-19 Vaccine

2.1.4. Public Service Message Framing, Media Type, and Willingness to Take COVID-19 Vaccine

2.1.5. Moderation of Skepticism towards COVID-19 Vaccines

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design, Participants, and Procedure

3.2. Instrumentation

3.2.1. Stimuli Selection Procedure and Manipulation Checks

3.2.2. Perceived Threat of COVID-19

3.2.3. Self-Efficacy towards COVID-19 Vaccine Immunization

3.2.4. Perceived Benefits of COVID-19 Vaccine

3.2.5. Skepticism towards COVID-19 Vaccines (Barriers)

3.2.6. Willingness to Take COVID-19 Vaccine

4. Results

4.1. Demographic and Preliminary Analysis

4.2. Manipulation Checks

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

4.5. Moderation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Vaccine Willingness

5.2. Trust in Vaccines

5.3. Vaccine Hesitancy

5.4. Managerial Implications

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Content of the Message for Group 1: Traditional Media–Public Service Message–Safety Benefits

Appendix A.2. Content of the Message for Group 2: Digital Media–Public Service Message–Safety Benefits

Appendix A.3. Content of the Message for Group 3: Traditional Media–Public Service Message–Fear Appraisals

Appendix A.4. Content of the Message for Group 4: Digital Media–Public Service Message–Fear Appraisals

References

- Adhikari, S.P.; Meng, S.; Wu, Y.-J.; Mao, Y.-P.; Ye, R.-X.; Wang, Q.-Z.; Sun, C.; Sylvia, S.; Rozelle, S.; Raat, H.; et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: A scoping review. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Meng, S.; Shi, J.; Lu, L. 2019-nCoV epidemic: Address mental health care to empower society. Lancet 2020, 395, e37–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ittefaq, M.; Hussain, S.A.; Fatima, M. COVID-19 and social-politics of medical misinformation on social media in Pakistan. Media Asia 2020, 47, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.A.; Baloch, M.; Ahmed, N.; Ali, A.A.; Iqbal, A. The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—An emerging global health threat. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 644–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.O.-Y.; Bailey, A.; Huynh, D.; Chan, J. YouTube as a source of information on COVID-19: A pandemic of misinformation? BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba, S.; de Figueiredo, A.; Piatek, S.J.; de Graaf, K.; Larson, H.J. Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Han, B.; Zhao, T.; Liu, H.; Liu, B.; Chen, L.; Xie, M.; Liu, J.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, S.; et al. Vaccination willingness, vaccine hesitancy, and estimated coverage at the first round of COVID-19 vaccination in China: A national cross-sectional study. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2833–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, M.; Sylvester, S.; Callaghan, T.; Lunz-Trujillo, K. Encouraging COVID-19 vaccine uptake through effective health communication. Front. Political Sci. 2021, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, S.A.; Villela, E.F.D.M.; Siau, C.; Chen, W.; Pengpid, S.; Hasan, M.; Sessou, P.; Ditekemena, J.; Amodan, B.; Hosseinipour, M.; et al. Factors affecting COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: An international survey among low- and middle-income countries. Vaccines 2021, 9, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidry, J.P.; Laestadius, L.I.; Vraga, E.K.; Miller, C.A.; Perrin, P.B.; Burton, C.W.; Ryan, M.; Fuemmeler, B.F.; Carlyle, K.E. Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine with and without emergency use authorization. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, E.; Laberge, C.; Guay, M.; Bramadat, P.; Roy, R.; Bettinger, J.A. Vaccine hesitancy: An overview. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2013, 9, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, S.C.; Jamison, A.M.; An, J.; Hancock, G.R.; Freimuth, V.S. Measuring vaccine hesitancy, confidence, trust and flu vaccine uptake: Results of a national survey of white and african American adults. Vaccine 2019, 37, 1168–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latkin, C.A.; Dayton, L.; Yi, G.; Konstantopoulos, A.; Boodram, B. Trust in a COVID-19 vaccine in the U.S.: A social-ecological perspective. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 270, 113684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, D.; Jamieson, K.H. Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 263, 113356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, N.; Coomes, E.A.; Haghbayan, H.; Gunaratne, K. Social media and vaccine hesitancy: New updates for the era of COVID-19 and globalized infectious diseases. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 2586–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basch, C.H.; Zybert, P.; Reeves, R. What do popular YouTubeTM videos say about vaccines? Child Care Health Dev. 2017, 43, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blankenship, E.B. Sentiment, contents, and retweets: A study of two vaccine-related twitter datasets. Perm. J. 2018, 22, 17–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basch, C.H.; MacLean, S.A. A content analysis of HPV related posts on instagram. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 15, 1476–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretti-Watel, P.; Seror, V.; Cortaredona, S.; Launay, O.; Raude, J.; Verger, P.; Fressard, L.; Beck, F.; Legleye, S.; L’Haridon, O.; et al. A future vaccination campaign against COVID-19 at risk of vaccine hesitancy and politicisation. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 769–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S.M.; Smith, L.E.; Sim, J.; Amlôt, R.; Cutts, M.; Dasch, H.; Rubin, G.J.; Sevdalis, N. COVID-19 vaccination intention in the UK: Results from the COVID-19 vaccination acceptability study (CoVAccS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 1612–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, P.; Rocha, J.V.; Moniz, M.; Gama, A.; Laires, P.A.; Pedro, A.R.; Dias, S.; Leite, A.; Nunes, C. Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, P.L.; Pennell, M.L.; Katz, M.L. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine 2020, 38, 6500–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann-Böhme, S.; Varghese, N.E.; Sabat, I.; Barros, P.P.; Brouwer, W.; Van Exel, J.; Schreyögg, J.; Stargardt, T. Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2020, 21, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caserotti, M.; Girardi, P.; Rubaltelli, E.; Tasso, A.; Lotto, L.; Gavaruzzi, T. Associations of COVID-19 risk perception with vaccine hesitancy over time for Italian residents. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 272, 113688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, A.; Ittefaq, M.; Abwao, M. #Scamdemic, #plandemic, or #scaredemic: What parler social media platform tells us about COVID-19 vaccine. Vaccines 2021, 9, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhazmi, A.; Alamer, E.; Daws, D.; Hakami, M.; Darraj, M.; Abdelwahab, S.; Maghfuri, A.; Algaissi, A. Evaluation of Side Effects Associated with COVID-19 Vaccines in Saudi Arabia. Vaccines 2021, 9, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Q. Mental health toll from the coronavirus: Social media usage reveals Wuhan residents’ depression and secondary trauma in the COVID-19 outbreak. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 114, 106524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Li, K.X.; Ma, F.; Wang, X. The effect of emotional appeal on seafarers’ safety behaviour: An extended health belief model. J. Transp. Health 2020, 16, 100810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luquis, R.R.; Kensinger, W.S. Applying the health belief model to assess prevention services among young adults. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2018, 57, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsulaiman, S.A.; Rentner, T.L. The health belief model and preventive measures: A study of the ministry of health campaign on coronavirus in Saudi Arabia. J. Int. Crisis Risk Commun. Res. 2018, 1, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Green, E.C.; Murphy, E.M.; Gryboski, K. The health belief model. In The Wiley Encyclopedia of Health Psychology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; Volume 2, pp. 211–214. [Google Scholar]

- Shafer, A.; Kaufhold, K.; Luo, Y. Applying the health belief model and an integrated behavioral model to promote breast tissue donation among Asian Americans. Health Commun. 2017, 33, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McWhirter, J.E.; Hoffman-Goetz, L. Application of the health belief model to U.S. magazine text and image coverage of skin cancer and recreational tanning (2000–2012). J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.L.; Jensen, J.D.; Scherr, C.L.; Brown, N.R.; Christy, K.; Weaver, J. The health belief model as an explanatory framework in communication research: Exploring parallel, serial, and moderated mediation. Health Commun. 2015, 30, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, L.; Wang, J.; Nicholas, S.; Maitland, E.; Leng, A.; Liu, R. The intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccine in China: Insights from protection motivation theory. Vaccines 2021, 9, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quick, B.L. Applying the health belief model to examine news coverage regarding steroids in sports by ABC, CBS, and NBC between March 1990 and May 2008. Health Commun. 2010, 25, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, C.J. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of health belief model variables in predicting behavior. Health Commun. 2010, 25, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raza, S.; Zaman, U.; Ferreira, P.; Farías, P. An experimental evidence on public acceptance of genetically modified food through advertisement framing on health and environmental benefits, objective knowledge, and risk reduction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paek, H.-J.; Hove, T. Risk perceptions and risk characteristics. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.-W.; Kim, J.; Lee, Y. The effect of health beliefs, media perceptions, and communicative behaviors on health behavioral intention: An integrated health campaign model on social media. Health Commun. 2018, 33, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, V.; Durante, A.; Ambrosca, R.; Arcadi, P.; Graziano, G.; Pucciarelli, G.; Simeone, S.; Vellone, E.; Alvaro, R.; Cicolini, G. Anxiety, sleep disorders and self-efficacy among nurses during COVID-19 pandemic: A large cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 1360–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. Message framing and interpersonal orientation at cultural and individual levels: Involvement as a moderator. Int. J. Advert. 2010, 29, 765–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Noort, G.; Antheunis, M.L.; Van Reijmersdal, E.A. Social connections and the persuasiveness of viral campaigns in social network sites: Persuasive intent as the underlying mechanism. J. Mark. Commun. 2012, 18, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.A.A.; Wahid, N.A. Endorser credibility effects on Yemeni male consumer’s attitudes towards advertising, brand attitude and purchase intention: The mediating role of attitude toward brand. Int. Bus. Res. 2012, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meulenaer, S.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Dens, N. Power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and the effects of source credibility on health risk message compliance. Health Commun. 2017, 33, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.W.; Ho, S.S.; Chow, J.K.; Wu, Y.Y.; Yang, Z. Communication and knowledge as motivators: Understanding Singaporean women’s perceived risks of breast cancer and intentions to engage in preventive measures. J. Risk Res. 2013, 16, 879–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, B.; Mostert, F.J.; Mostert, J.H. Financial innovation in retail banking in South Africa. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2016, 13, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulat, J.S.; Prabandari, Y.S.; Sanusi, R.; Hapsari, E.D.; Santoso, B. The validity of health belief model variables in predicting behavioral change. Health Educ. 2018, 118, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, W.; Ittefaq, M.; Seo, H.; Naz, F. Factors associated with the belief in COVID-19 related conspiracy theories in Pakistan. Health Risk Soc. 2021, 23, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, R.; Lamberty, P. A bioweapon or a hoax? The link between distinct conspiracy beliefs about the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak and pandemic behavior. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2020, 11, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, A.; Žeželj, I. A systematic review of narrative interventions: Lessons for countering anti-vaccination conspiracy theories and misinformation. Public Underst. Sci. 2021, 096366252110118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, A.A.; Celedón, J.C. COVID-19 vaccination: Helping the latinx community to come forward. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 35, 100860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoda, T.; Katsuyama, H. Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination in Japan. Vaccines 2021, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentler, P.M.; Chou, C.-P. Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1987, 16, 78–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, W.; Babin, B.J. Multivariate data analysis: Its approach, evolution, and impact. In The Great Facilitator; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Geuens, M.; De Pelsmacker, P. Planning and conducting experimental advertising research and questionnaire design. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawshe, C.H. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers. Psychol. 1975, 28, 563–575. Available online: http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x (accessed on 11 May 2021). [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.H.; Abu Bakar, H.; Mohamad, B. Advertising appeals and Malaysian culture norms. J. Asian Pac. Commun. 2018, 28, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.L.; Nicholls, A.R.; Clough, P.J.; Crust, L. Assessing model fit: Caveats and recommendations for confirmatory factor analysis and exploratory structural equation modeling. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2015, 19, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.; Balla, J.R.; McDonald, R.P. Goodness-of-fit indexes in confirmatory factor analysis: The effect of sample size. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Implications for public health communications. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artime, O.; D’Andrea, V.; Gallotti, R.; Sacco, P.L.; De Domenico, M. Effectiveness of dismantling strategies on moderated vs. unmoderated online social platforms. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M.J.; Harris, E.A.; Fielding, K. The psychological roots of anti-vaccination attitudes: A 24-nation investigation. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Young, R.; Wu, X.; Zhu, G. Effects of vaccine-related conspiracy theories on Chinese young adults’ perceptions of the HPV vaccine: An experimental study. Health Commun. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 179 | 55.9 |

| Female | 141 | 44.1 |

| Medical History | ||

| Yes | 63 | 19.7 |

| No | 257 | 80.3 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Yes | 177 | 55.3 |

| No | 143 | 44.7 |

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | 68 | 21.2 |

| 30–44 | 127 | 39.7 |

| 45–59 | 94 | 29.4 |

| 60 and above | 31 | 9.7 |

| Education level | ||

| High School Certificate | 77 | 24.1 |

| College/Diploma | 152 | 47.5 |

| University Degree | 91 | 28.4 |

| G 1 | Mean | PT | PB | SE | PSM | SV | WTV | G 2 | Mean | PT | PB | SE | PSM | SV | WTV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT | 3.25 | 1 | PT | 2.89 | 1 | ||||||||||

| PB | 3.65 | 0.41 * | 1 | PB | 3.19 | 0.37 * | 1 | ||||||||

| SE | 3.56 | 0.56 * | 0.37 * | 1 | SE | 3.72 | 0.43 * | 0.47 * | 1 | ||||||

| PSM | 3.81 | 0.37 * | 0.39 * | 0.40 * | 1 | PSM | 3.54 | 0.29 * | 0.37 * | 0.44 * | 1 | ||||

| SV | 2.78 | −0.31 * | −0.56 * | −0.38 * | −0.27 * | 1 | SV | 2.96 | −0.16 * | −0.13 * | −0.22 | −0.18 * | 1 | ||

| WTV | 4.09 | 0.35 * | 0.33 * | 0.19 * | 0.39 * | −0.12 | 1 | WTV | 3.89 | 0.25 * | 0.32 * | 0.19 * | 0.17 * | −0.34 * | 1 |

| G 3 | Mean | PT | PB | SE | PSM | SV | WTV | G 4 | Mean | PT | PB | SE | PSM | SV | WTV |

| PT | 4.57 | 1 | PT | 4.13 | 1 | ||||||||||

| PB | 4.48 | 0.39 * | 1 | PB | 4.23 | 0.28 * | 1 | ||||||||

| SE | 4.35 | 0.43 * | 0.37 * | 1 | SE | 3.98 | 0.31 * | 0.65 * | 1 | ||||||

| PSM | 4.56 | 0.62 * | 0.48 * | 0.44 * | 1 | PSM | 4.29 | 0.36 * | 0.76 * | 0.65 * | 1 | ||||

| SV | 2.38 | −0.47 * | −0.26 * | −0.34 | −0.43 * | 1 | SV | 2.60 | −0.08 | −0.24 * | −0.20 * | −0.14 * | 1 | ||

| WTV | 4.43 | 0.29 * | 0.38 * | 0.25 * | 0.57 * | −0.27 | 1 | WTV | 4.28 | 0.38 * | 0.23 * | 0.38 * | 0.27 * | −0.09 | 1 |

| Measurement Models | x2 | x2/df | GFI | TLI | IFI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: Traditional Media–Public Service Message–Safety Benefits | 2379 | 3.56 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.042 |

| Group 2: Digital Media–Public Service Message–Safety Benefits | 1822 | 2.67 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.045 |

| Group 3: Traditional Media–Public Service Message–Fear Appraisals | 1547 | 1.97 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.037 |

| Group 4: Digital Media–Public Service Message–Fear Appraisals | 1169 | 3.34 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.032 |

| Structural Models | x2/DF | GFI | TLI | IF | CFI | RMS | |

| Group 1: Traditional Media–Public Service Message–Safety Benefits | 1052 | 3.79 | 0.91 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.051 |

| Group 2: Digital Media–Public Service Message–Safety Benefits | 867 | 3.18 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.045 |

| Group 3: Traditional Media–Public Service Message–Fear Appraisals | 1493 | 2.15 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 0.033 |

| Group 4: Digital Media–Public Service Message–Fear Appraisals | 1743 | 3.43 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.041 |

| Items | Group 1: Traditional Media–Public Service Message–Safety Benefits | Group 2: Digital Media–Public Service Message–Safety Benefits | Group 3: Traditional Media–Public Service Message–Fear Appraisals | Group 4: Digital Media–Public Service Message–Fear Appraisals | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | CR | AVE | L | α | CR | AVE | W | α | CR | AVE | L | α | CR | AVE | L | |

| PT1 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.73 | 0.86 | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.70 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.82 | 0.61 | 0.71 |

| PT2 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 0.94 | 0.87 | ||||||||||||

| PT3 | 0.95 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.75 | ||||||||||||

| PT4 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.38 * | ||||||||||||

| PB1 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.74 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.96 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.67 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.74 | 0.87 |

| PB2 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.85 | ||||||||||||

| SE1 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.70 | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.85 | 0.66 | 0.89 | 0.75 | 0.84 | 0.64 | 0.78 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.76 | 0.93 |

| SE2 | 0.76 | 0.82 | 0.93 | 0.82 | ||||||||||||

| SE3 | 0.89 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.87 | ||||||||||||

| PSM1 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.74 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.73 | 0.95 | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.62 | 0.76 |

| PSM2 | 0.78 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.82 | ||||||||||||

| PSM3 | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.73 | 0.79 | ||||||||||||

| SV1 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.69 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.68 | 0.78 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.74 | 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.63 | 0.76 |

| SV2 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.83 | ||||||||||||

| SV3 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.87 | 0.92 | ||||||||||||

| SV4 | 0.77 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 0.75 | ||||||||||||

| SV5 | 0.73 | 0.32 * | 0.88 | 0.68 | ||||||||||||

| WTV1 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.90 | 0.73 | 0.85 | 0.65 | 0.76 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.93 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.67 | 0.88 |

| WTV2 | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.89 | 0.81 | ||||||||||||

| WTV3 | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.76 | ||||||||||||

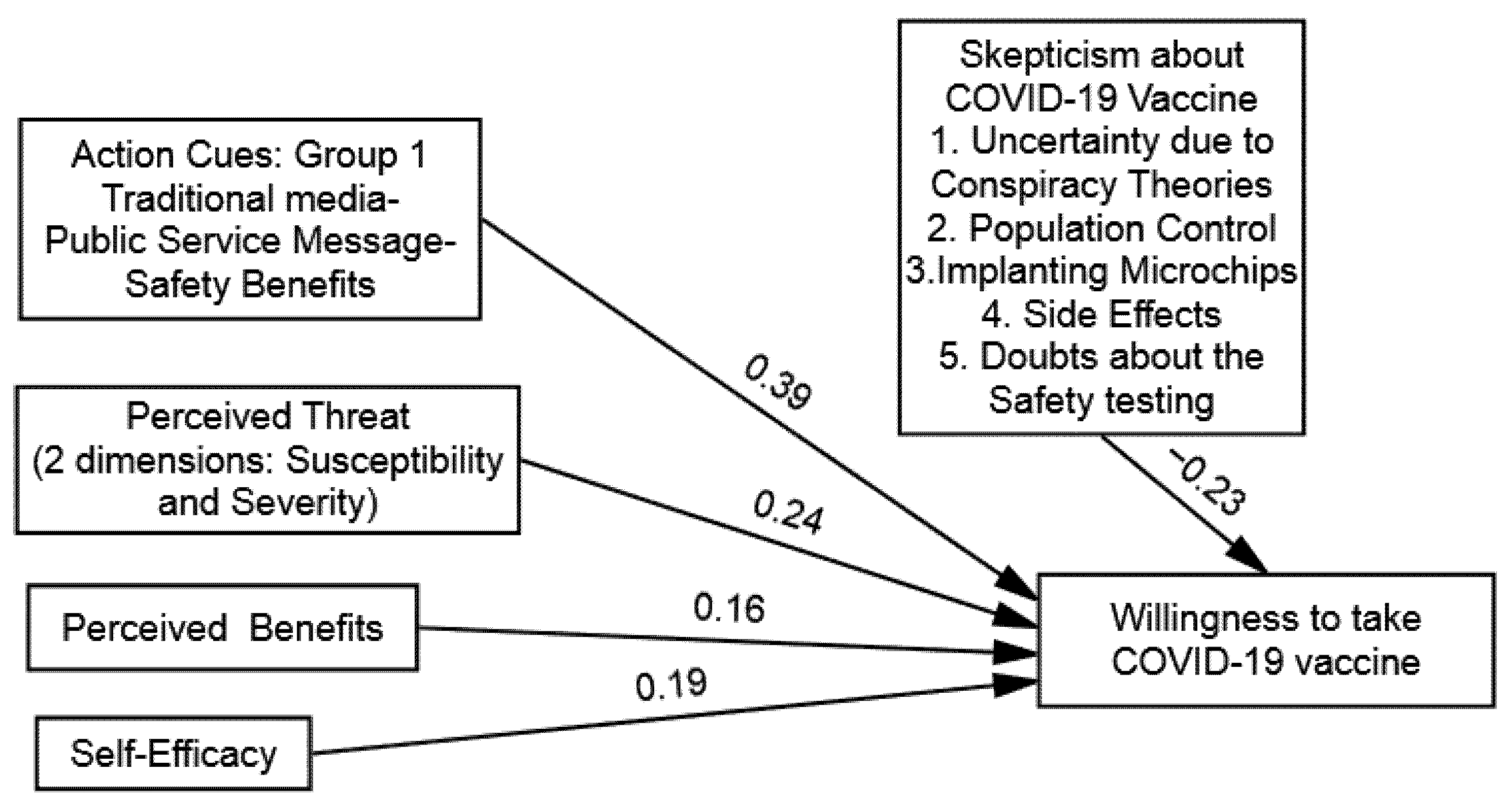

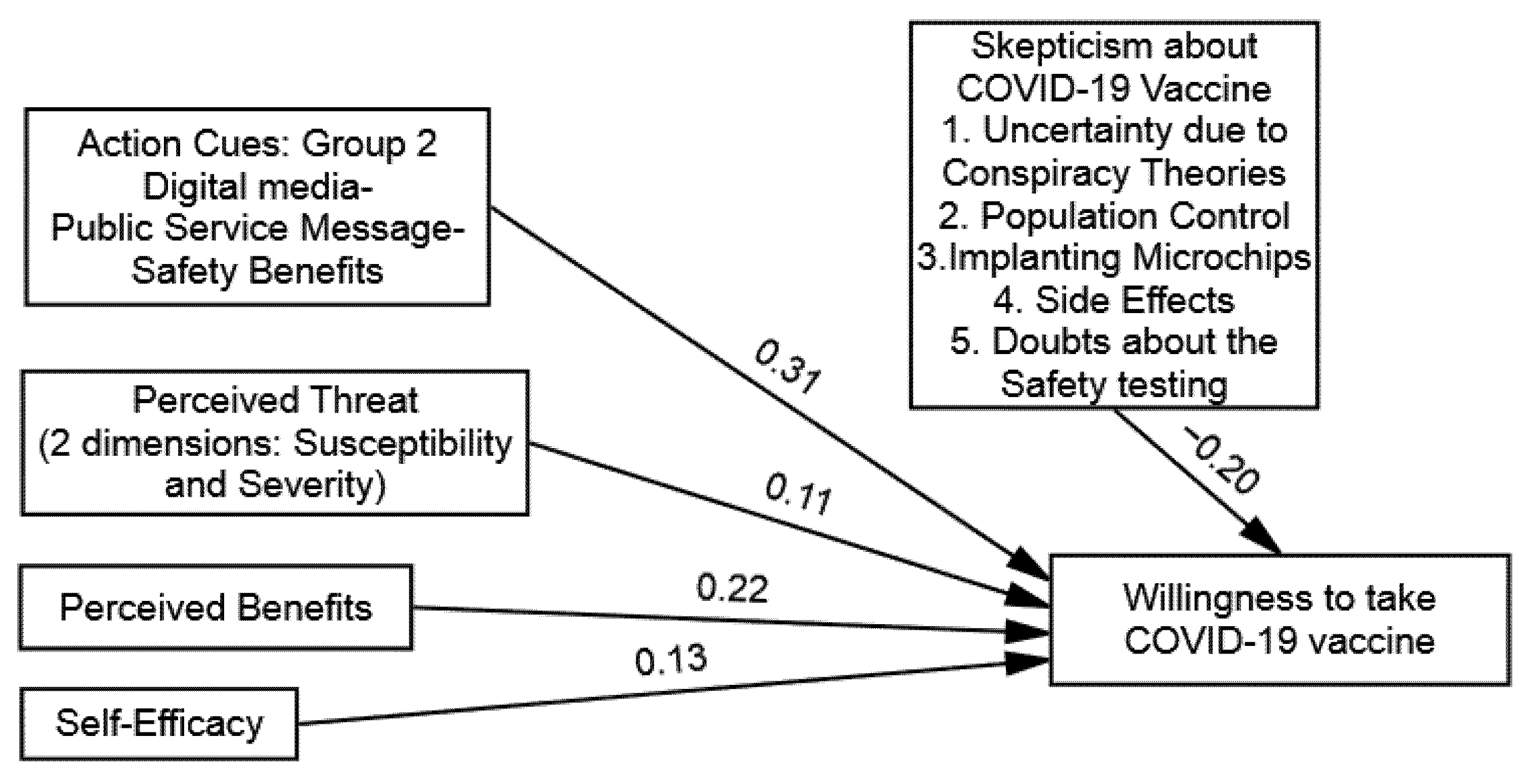

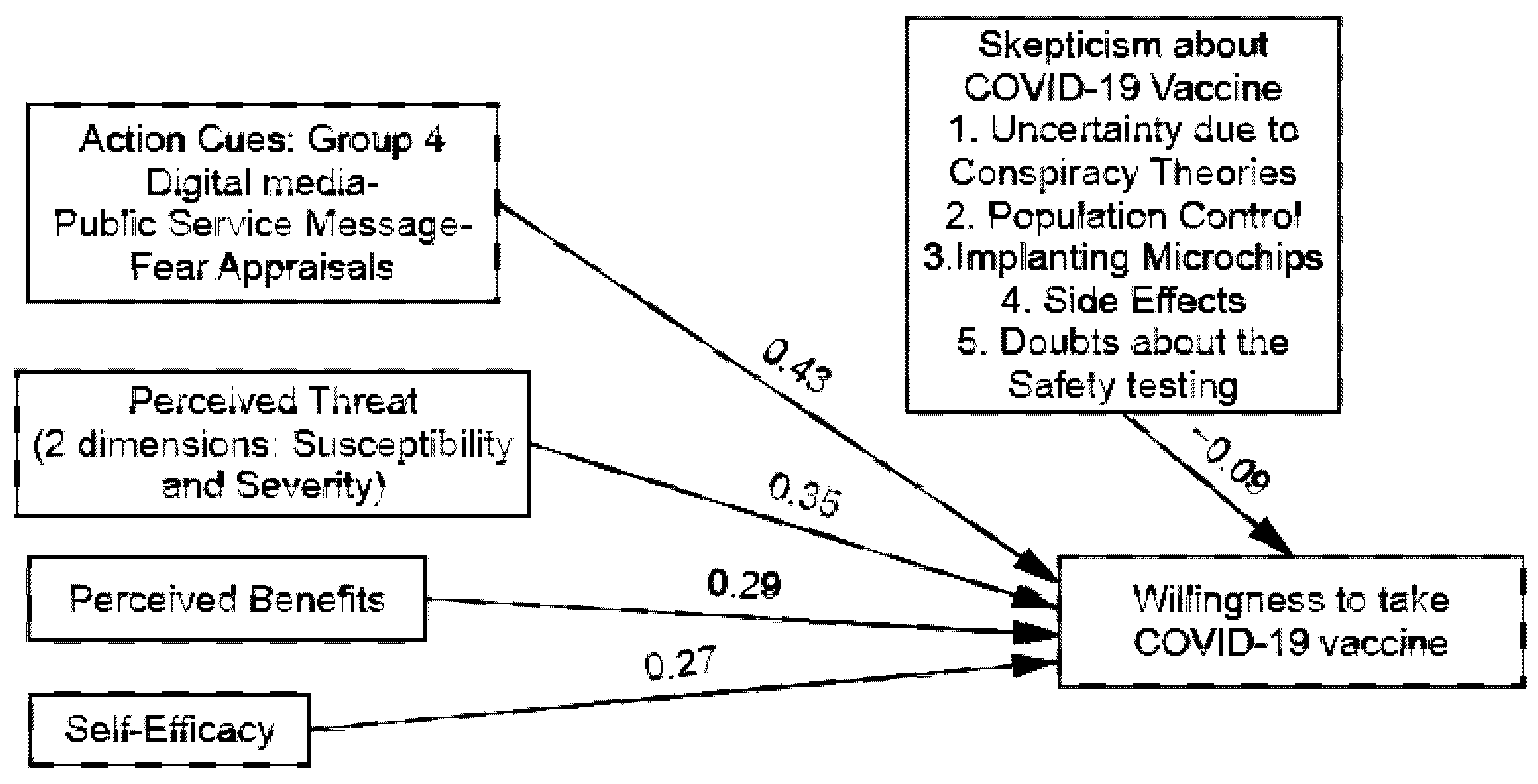

| Direct Influence | PT→WTV (H1) | PB→WTV (H2) | SE→WTV (H3) | PSM→WTV (H4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: Traditional Media–Public Service Message–Safety Benefits | 0.24 * | 0.16 * | 0.19 * | 0.39 * |

| Group 2: Digital Media–Public Service Message–Safety Benefits | 0.11 * | 0.22 * | 0.13 * | 0.31 * |

| Group 3: Traditional Media–Public Service Message–Fear Appraisals | 0.39 * | 0.32 * | 0.24 * | 0.51 * |

| Group 4: Digital Media–Public Service Message–Fear Appraisals | 0.35 * | 0.29 * | 0.27 * | 0.43 * |

| Stepwise Moderation | Results |

|---|---|

| Group 1: Traditional Media–Public Service Message–Safety Benefits, Dependent Variables: WTV | |

| Step 1: Independent Variables: Public Service Message | 0.39 * (5.21) |

| Skepticisms towards COVID-19 Vaccines | −0.23 * (2.34) |

| R2 Step 2: Moderator: Public Service Message X Skepticism towards COVID-19 Vaccines | 0.57 |

| −0.14 * (3.56) | |

| R2 | 0.47 |

| ΔR2 | −0.10 |

| Group 2: Digital Media–Public Service Message–Safety Benefits, Dependent Variables: WTV | |

| Step 1: Independent Variables: Public Service Message | 0.31 * (4.79) |

| Skepticisms towards COVID-19 Vaccines | −0.20 * (7.35) |

| R2 Step 2: Moderator: Public Service Message X Skepticism towards COVID-19 Vaccines | 0.41 |

| −0.26 * (5.63) | |

| R2 | 0.32 |

| ΔR2 | −0.08 |

| Group 3: Traditional Media–Public Service Message–Fear Appraisals, Dependent Variables: WTV | |

| Step 1: Independent Variables: Public Service Message | 0.51 * (4.37) |

| Skepticisms towards COVID-19 Vaccines | −0.17 * (6.59) |

| R2 Step 2: Moderator: Public Service Message X Skepticism towards COVID-19 Vaccines | 0.71 |

| −0.09 * (6.27) | |

| R2 | 0.65 |

| ΔR2 | −0.06 |

| Group 4: Digital Media–Public Service Message–Fear Appraisals, Dependent Variables: WTV | |

| Step 1: Independent Variables: Public Service Message | 0.43 * (3.68) |

| Skepticisms towards COVID-19 Vaccines | −0.09 * (7.19) |

| R2 Step 2: Moderator: Public Service Message X Skepticism towards COVID-19 Vaccines | 0.61 |

| −0.11 * (9.26) | |

| R2 | 0.57 |

| ΔR2 | −0.04 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, Q.; Raza, S.H.; Yousaf, M.; Zaman, U.; Siang, J.M.L.D. Can Communication Strategies Combat COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy with Trade-Off between Public Service Messages and Public Skepticism? Experimental Evidence from Pakistan. Vaccines 2021, 9, 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9070757

Jin Q, Raza SH, Yousaf M, Zaman U, Siang JMLD. Can Communication Strategies Combat COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy with Trade-Off between Public Service Messages and Public Skepticism? Experimental Evidence from Pakistan. Vaccines. 2021; 9(7):757. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9070757

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Qiang, Syed Hassan Raza, Muhammad Yousaf, Umer Zaman, and Jenny Marisa Lim Dao Siang. 2021. "Can Communication Strategies Combat COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy with Trade-Off between Public Service Messages and Public Skepticism? Experimental Evidence from Pakistan" Vaccines 9, no. 7: 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9070757

APA StyleJin, Q., Raza, S. H., Yousaf, M., Zaman, U., & Siang, J. M. L. D. (2021). Can Communication Strategies Combat COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy with Trade-Off between Public Service Messages and Public Skepticism? Experimental Evidence from Pakistan. Vaccines, 9(7), 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9070757