High Rates of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Association with Conspiracy Beliefs: A Study in Jordan and Kuwait among Other Arab Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Survey Items

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

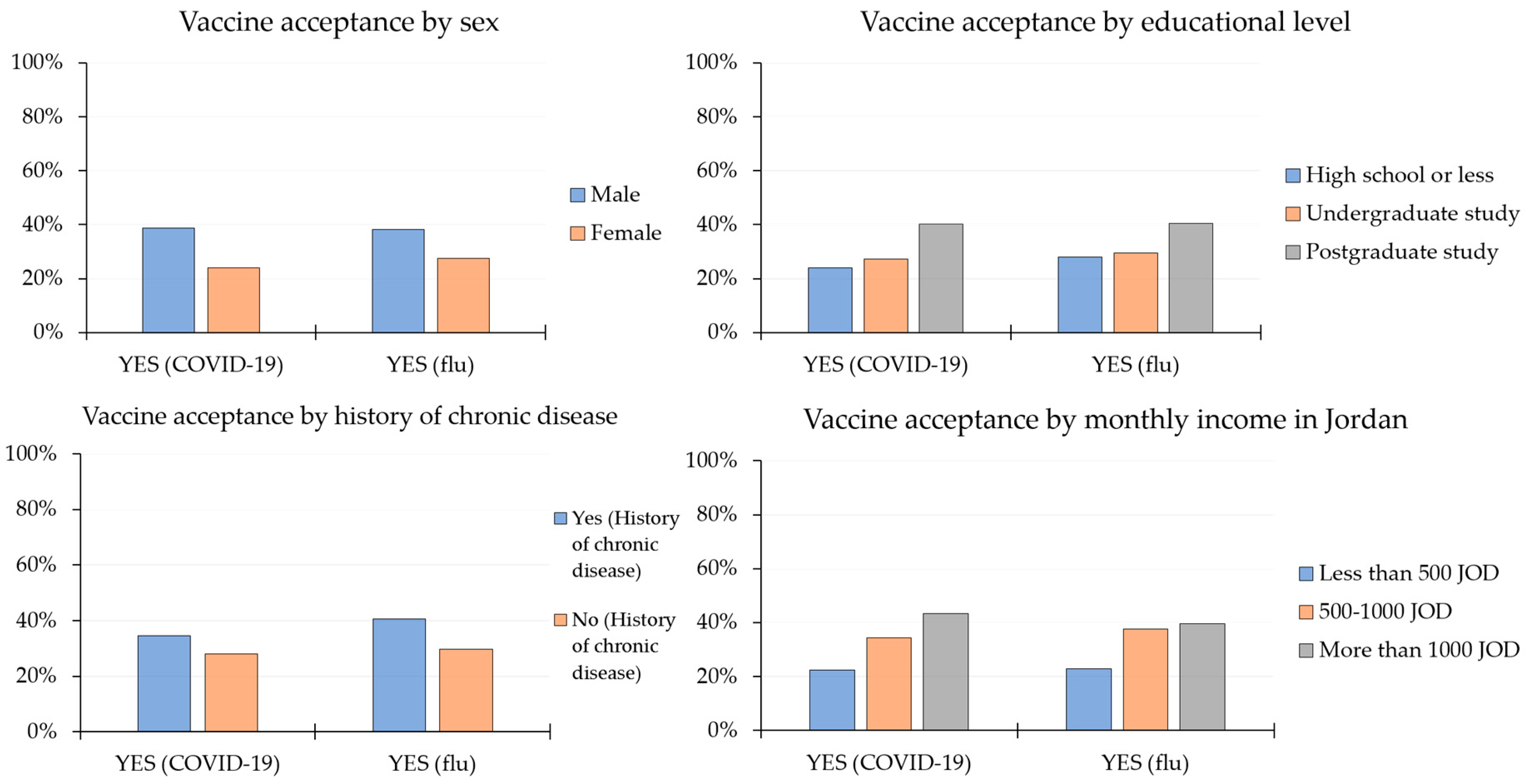

3.2. Rates of Vaccine Acceptance and Related Factors

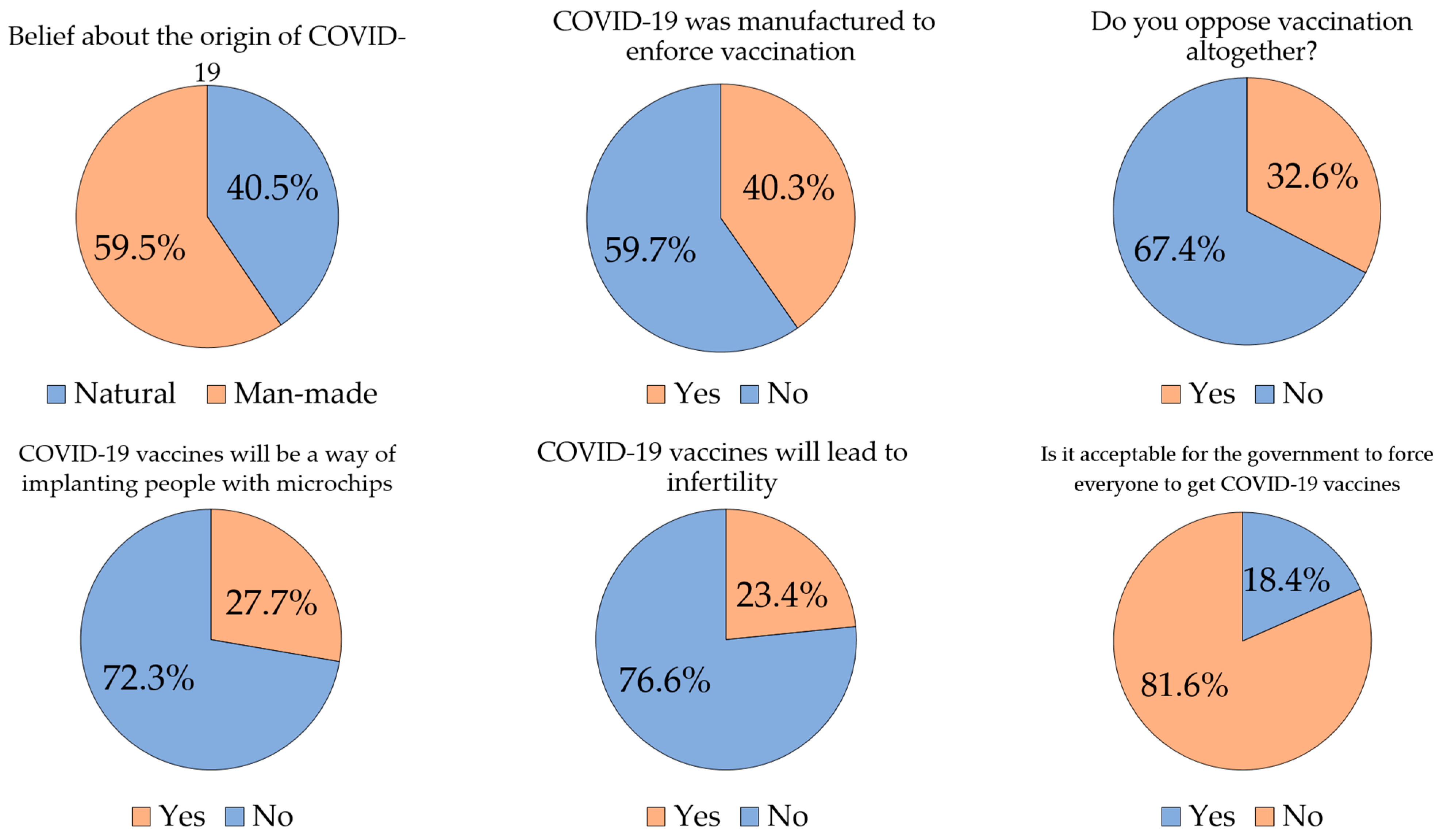

3.3. Vaccine Acceptance and Conspiracy Beliefs

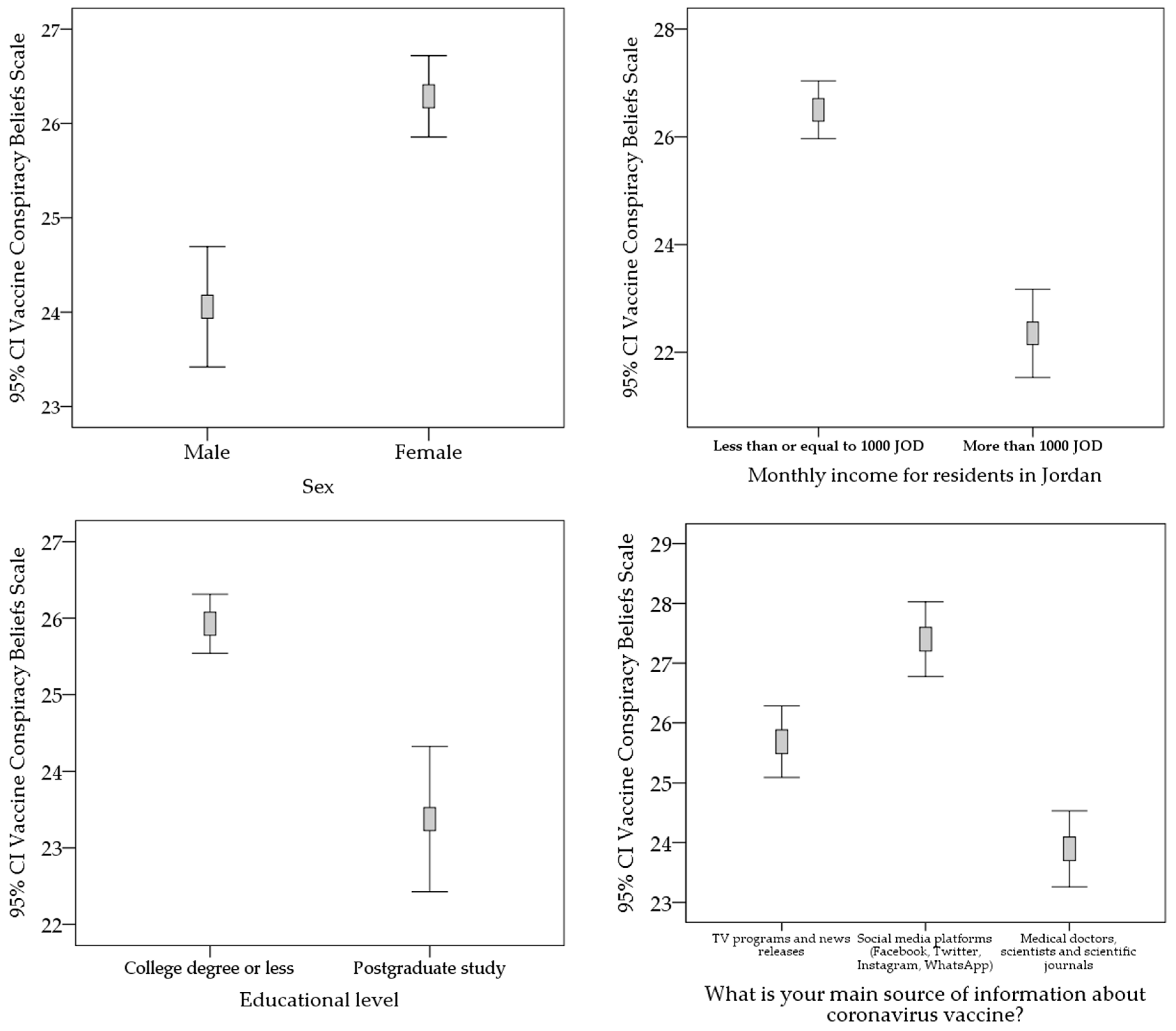

3.4. Vaccine Acceptance and VCBS

3.5. Sources of Information about COVID-19 Vaccines

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MacDonald, N.E.; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poland, G.A.; Jacobson, R.M. The age-old struggle against the antivaccinationists. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, J.E.; Wood, T. Medical conspiracy theories and health behaviors in the United States. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salali, G.D.; Uysal, M.S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is associated with beliefs on the origin of the novel coronavirus in the UK and Turkey. Psychol. Med. 2020, 10, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadke, V.K.; Bednarczyk, R.A.; Salmon, D.A.; Omer, S.B. Association Between Vaccine Refusal and Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in the United States: A Review of Measles and Pertussis. JAMA 2016, 315, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostvogel, P.M.; van Wijngaarden, J.K.; van der Avoort, H.G.; Mulders, M.N.; Conyn-van Spaendonck, M.A.; Rumke, H.C.; van Steenis, G.; van Loon, A.M. Poliomyelitis outbreak in an unvaccinated community in The Netherlands, 1992–1993. Lancet 1994, 344, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, V.A.; Stollenwerk, N.; Jensen, H.J.; Ramsay, M.E.; Edmunds, W.J.; Rhodes, C.J. Measles outbreaks in a population with declining vaccine uptake. Science 2003, 301, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: Classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, A.A.; Dinani, M.M.; Madavani, A.N.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.X. The distress of Iranian adults during the Covid-19 pandemic—More distressed than the Chinese and with different predictors. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 124–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgantini, L.A.; Naha, U.; Wang, H.; Francavilla, S.; Acar, O.; Flores, J.M.; Crivellaro, S.; Moreira, D.; Abern, M.; Eklund, M.; et al. Factors contributing to healthcare professional burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid turnaround global survey. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Baticulon, R.E.; Kadhum, M.; Alser, M.; Ojuka, D.K.; Badereddin, Y.; Kamath, A.; Parepalli, S.A.; Brown, G.; Iharchane, S.; et al. Infection and mortality of healthcare workers worldwide from COVID-19: A systematic review. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e003097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukaetova-Ladinska, E.B.; Kronenberg, G. Psychological and neuropsychiatric implications of COVID-19. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, M.; Alsafi, Z.; Sohrabi, C.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, M.; Agha, R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 78, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldometer. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 6 January 2020).

- Hodgson, S.H.; Mansatta, K.; Mallett, G.; Harris, V.; Emary, K.R.W.; Pollard, A.J. What defines an efficacious COVID-19 vaccine? A review of the challenges assessing the clinical efficacy of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, C.; Sogni, F.; Affanni, P.; Veronesi, L.; Argentiero, A.; Esposito, S. Vaccines against Coronaviruses: The State of the Art. Vaccines 2020, 8, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.P.; Gupta, V. COVID-19 Vaccine: A comprehensive status report. Virus Res. 2020, 288, 198114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Draft Landscape of COVID-19 Candidate Vaccines. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines (accessed on 26 December 2020).

- Wang, J.; Peng, Y.; Xu, H.; Cui, Z.; Williams, R.O., 3rd. The COVID-19 Vaccine Race: Challenges and Opportunities in Vaccine Formulation. AAPS PharmsciTech 2020, 21, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, O.; Sultan, A.A.; Ding, H.; Triggle, C.R. A Review of the Progress and Challenges of Developing a Vaccine for COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 585354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teerawattananon, Y.; Dabak, S.V. COVID Vaccination Logistics: Five Steps to Take Now; Nature Publishing Group: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dror, A.A.; Eisenbach, N.; Taiber, S.; Morozov, N.G.; Mizrachi, M.; Zigron, A.; Srouji, S.; Sela, E. Vaccine hesitancy: The next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, E.; Laberge, C.; Guay, M.; Bramadat, P.; Roy, R.; Bettinger, J. Vaccine hesitancy: An overview. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 2013, 9, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palamenghi, L.; Barello, S.; Boccia, S.; Graffigna, G. Mistrust in biomedical research and vaccine hesitancy: The forefront challenge in the battle against COVID-19 in Italy. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 785–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abo, S. Is a COVID-19 Vaccine Likely to Make Things Worse? Vaccines 2020, 8, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billah, M.A.; Miah, M.M.; Khan, M.N. Reproductive number of coronavirus: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on global level evidence. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.M.; Vegvari, C.; Truscott, J.; Collyer, B.S. Challenges in creating herd immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection by mass vaccination. Lancet 2020, 396, 1614–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.C.; Dubey, V. Addressing vaccine hesitancy: Clinical guidance for primary care physicians working with parents. Can. Fam. Physician. 2019, 65, 175–181. [Google Scholar]

- Salmon, D.A.; Dudley, M.Z.; Glanz, J.M.; Omer, S.B. Vaccine hesitancy: Causes, consequences, and a call to action. Vaccine 2015, 33 (Suppl. 4), D66–D71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Figueiredo, A.; Simas, C.; Karafillakis, E.; Paterson, P.; Larson, H.J. Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: A large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. Lancet 2020, 396, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, E.; Gagnon, D.; Nickels, E.; Jeram, S.; Schuster, M. Mapping vaccine hesitancy--country-specific characteristics of a global phenomenon. Vaccine 2014, 32, 6649–6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolley, D.; Douglas, K.M. The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M.J.; Lobera, J.; Diaz-Catalan, C. Vaccine hesitancy is strongly associated with distrust of conventional medicine, and only weakly associated with trust in alternative medicine. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 255, 113019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz Crescitelli, M.E.; Ghirotto, L.; Sisson, H.; Sarli, L.; Artioli, G.; Bassi, M.C.; Appicciutoli, G.; Hayter, M. A meta-synthesis study of the key elements involved in childhood vaccine hesitancy. Public Health 2020, 180, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertin, P.; Nera, K.; Delouvee, S. Conspiracy Beliefs, Rejection of Vaccination, and Support for hydroxychloroquine: A Conceptual Replication-Extension in the COVID-19 Pandemic Context. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 565128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romer, D.; Jamieson, K.H. Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the US. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 263, 113356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uscinski, J.E.; Enders, A.M.; Klofstad, C.; Seelig, M.; Funchion, J.; Everett, C.; Wuchty, S.; Premaratne, K.; Murthi, M. Why do people believe COVID-19 conspiracy theories? Harv. Kennedy Sch. Misinf. Rev. 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahsavari, S.; Holur, P.; Wang, T.; Tangherlini, T.R.; Roychowdhury, V. Conspiracy in the time of corona: Automatic detection of emerging COVID-19 conspiracy theories in social media and the news. J. Comput Soc. Sci 2020, 3, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Vidal-Alaball, J.; Downing, J.; Lopez Segui, F. COVID-19 and the 5G Conspiracy Theory: Social Network Analysis of Twitter Data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Dababseh, D.; Yaseen, A.; Al-Haidar, A.; Ababneh, N.A.; Bakri, F.G.; Mahafzah, A. Conspiracy Beliefs Are Associated with Lower Knowledge and Higher Anxiety Levels Regarding COVID-19 among Students at the University of Jordan. Int J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Dababseh, D.; Yaseen, A.; Al-Haidar, A.; Taim, D.; Eid, H.; Ababneh, N.A.; Bakri, F.G.; Mahafzah, A. COVID-19 misinformation: Mere harmless delusions or much more? A knowledge and attitude cross-sectional study among the general public residing in Jordan. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, G.K.; Holding, A.; Perez, S.; Amsel, R.; Rosberger, Z. Validation of the vaccine conspiracy beliefs scale. Papillomavirus Res. 2016, 2, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, B. The contribution of vaccination to global health: Past, present and future. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, P.; Maxmen, A. The epic battle against coronavirus misinformation and conspiracy theories. Nature 2020, 581, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, Y.H.; Mallhi, T.H.; Alotaibi, N.H.; Alzarea, A.I.; Alanazi, A.S.; Tanveer, N.; Hashmi, F.K. Threat of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Pakistan: The Need for Measures to Neutralize Misleading Narratives. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 603–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voysey, M.; Clemens, S.A.C.; Madhi, S.A.; Weckx, L.Y.; Folegatti, P.M.; Aley, P.K.; Angus, B.; Baillie, V.L.; Barnabas, S.L.; Bhorat, Q.E.; et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: An interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet 2020, 397, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahase, E. Covid-19: Moderna vaccine is nearly 95% effective, trial involving high risk and elderly people shows. BMJ Br. Med J. (Online) 2020, 371, 371. [Google Scholar]

- Mahase, E. Covid-19: Vaccine candidate may be more than 90% effective, interim results indicate. BMJ 2020, 371, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, S.B.; Yildirim, I.; Forman, H.P. Herd Immunity and Implications for SARS-CoV-2 Control. JAMA 2020, 324, 2095–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschwanden, C. The false promise of herd immunity for COVID-19. Nature 2020, 587, 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpass, D. Confronting the Economic and Financial Challenges of Covid-19: A Conversation with World Bank Group President David Malpass. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/speech/2020/12/14/confronting-the-economic-and-financial-challenges-of-covid-19-a-conversation-with-world-bank-group-president-david-malpass (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Harrison, E.A.; Wu, J.W. Vaccine confidence in the time of COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Threat Assessment Brief: Rapid Increase of a SARS-CoV-2 Variant with Multiple Spike Protein Mutations Observed in the United Kingdom. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/threat-assessment-brief-rapid-increase-sars-cov-2-variant-united-kingdom (accessed on 26 December 2020).

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: A systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogue, K.; Jensen, J.L.; Stancil, C.K.; Ferguson, D.G.; Hughes, S.J.; Mello, E.J.; Burgess, R.; Berges, B.K.; Quaye, A.; Poole, B.D. Influences on Attitudes Regarding Potential COVID-19 Vaccination in the United States. Vaccines 2020, 8, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, K.A.; Bloomstone, S.J.; Walder, J.; Crawford, S.; Fouayzi, H.; Mazor, K.M. Attitudes Toward a Potential SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine: A Survey of U.S. Adults. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Ratzan, S.C.; Palayew, A.; Gostin, L.O.; Larson, H.J.; Rabin, K.; Kimball, S.; El-Mohandes, A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat. Med. 2020, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harapan, H.; Wagner, A.L.; Yufika, A.; Winardi, W.; Anwar, S.; Gan, A.K.; Setiawan, A.M.; Rajamoorthy, Y.; Sofyan, H.; Mudatsir, M. Acceptance of a COVID-19 Vaccine in Southeast Asia: A Cross-Sectional Study in Indonesia. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jing, R.; Lai, X.; Zhang, H.; Lyu, Y.; Knoll, M.D.; Fang, H. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Vaccines 2020, 8, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Landry, C.A.; Paluszek, M.M.; Groenewoud, R.; Rachor, G.S.; Asmundson, G.J.G. A Proactive Approach for Managing COVID-19: The Importance of Understanding the Motivational Roots of Vaccination Hesitancy for SARS-CoV2. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 575950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graffigna, G.; Palamenghi, L.; Boccia, S.; Barello, S. Relationship between Citizens’ Health Engagement and Intention to Take the COVID-19 Vaccine in Italy: A Mediation Analysis. Vaccines 2020, 8, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, C. A future vaccination campaign against COVID-19 at risk of vaccine hesitancy and politicisation. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 769–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhopal, S.; Nielsen, M. Vaccine hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries: Potential implications for the COVID-19 response. Arch. Dis. Child. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohaithef, M.; Padhi, B.K. Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Saudi Arabia: A Web-Based National Survey. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2020, 13, 1657–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bednarczyk, R.A.; Chu, S.L.; Sickler, H.; Shaw, J.; Nadeau, J.A.; McNutt, L.A. Low uptake of influenza vaccine among university students: Evaluating predictors beyond cost and safety concerns. Vaccine 2015, 33, 1659–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, P.; Rauber, D.; Betsch, C.; Lidolt, G.; Denker, M.L. Barriers of Influenza Vaccination Intention and Behavior—A Systematic Review of Influenza Vaccine Hesitancy, 2005–2016. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Fahmy, S.; Rasool, B.A.; Khan, S. Influenza vaccination: Healthcare workers attitude in three Middle East countries. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2010, 7, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaidy, S.T.A.; Al Mayahi, Z.K.; Kaddoura, M.; Mahomed, O.; Lahoud, N.; Abubakar, A.; Zaraket, H. Influenza Vaccination Hesitancy among Healthcare Workers in South Al Batinah Governorate in Oman: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2020, 8, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Henningsen, K.H.; Brehaut, J.C.; Hoe, E.; Wilson, K. Acceptance of a pandemic influenza vaccine: A systematic review of surveys of the general public. Infect. Drug Resist. 2011, 4, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Gou, X.; Pu, K.; Chen, Z.; Guo, Q.; Ji, R.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Prevalence of comorbidities in the novel Wuhan coronavirus (COVID-19) infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 94, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Eaton, L.A.; Kalichman, S.C.; Brousseau, N.M.; Hill, E.C.; Fox, A.B. COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, health behaviors, and policy support. Transl. Behav. Med. 2020, 10, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.L.; Wiysonge, C. Social media and vaccine hesitancy. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e004206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.; Waite, F.; Rosebrock, L.; Petit, A.; Causier, C.; East, A.; Jenner, L.; Teale, A.L.; Carr, L.; Mulhall, S.; et al. Coronavirus conspiracy beliefs, mistrust, and compliance with government guidelines in England. Psychol. Med. 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaskiewicz, R. The Big Pharma conspiracy theory. Med. Writ. 2013, 22, 259–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, K.; Durrheim, D.N.; Jones, A.; Butler, M. Acceptance of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza vaccination by the Australian public. Med. J. Aust. 2010, 192, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, J.; Uscher-Pines, L.; Harris, K.M. Perceived seriousness of seasonal and A (H1N1) influenzas, attitudes toward vaccination, and vaccine uptake among US adults: Does the source of information matter? Prev. Med. 2010, 51, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, K.; Kumari, P.; Saha, L. COVID-19 vaccine: A recent update in pipeline vaccines, their design and development strategies. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 892, 173751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Country of Residence | Jordan | Kuwait | Saudi Arabia | Others 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n 4 (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Respondents | 2173 (63.6) | 771 (22.6) | 154 (4.5) | 316 (9.3) | |

| Age category based on quartiles 1 | 16–21 years | 755 (34.7) | 156 (20.2) | 10 (6.5) | 68 (21.5) |

| 22–26 years | 480 (22.1) | 163 (21.1) | 21 (13.6) | 120 (38.0) | |

| 27–39 years | 419 (19.3) | 254 (32.9) | 49 (31.8) | 76 (24.1) | |

| 40 years or older | 519 (23.9) | 198 (25.7) | 74 (48.1) | 52 (16.5) | |

| Sex | Male | 665 (30.6) | 278 (36.1) | 36 (23.4) | 136 (43.0) |

| Female | 1508 (69.4) | 493 (63.9) | 118 (76.6) | 180 (57.0) | |

| Monthly income for residents in Jordan 2 | Less than 500 JOD | 688 (32.3) | - | - | - |

| 500–1000 JOD | 826 (38.8) | - | - | - | |

| More than 1000 JOD | 616 (28.9) | - | - | - | |

| Educational level 3 | High school or less | 173 (8.0) | 137 (17.8) | 22 (14.3) | 27 (8.5) |

| Undergraduate | 1646 (75.7) | 560 (72.6) | 111 (72.1) | 245 (77.5) | |

| Postgraduate | 354 (16.3) | 74 (9.6) | 21 (13.6) | 44 (13.9) | |

| History of chronic disease | Yes | 205 (9.4) | 103 (13.4) | 21 (13.6) | 32 (10.1) |

| No | 1968 (90.6) | 668 (86.6) | 133 (86.4) | 284 (89.9) | |

| Experience of COVID-19 in self or family | Yes | 781 (35.9) | 392 (50.8) | 60 (39.0) | 122 (38.6) |

| No | 1392 (64.1) | 379 (49.2) | 94 (61.0) | 194 (61.4) |

| Variable | Will You Get COVID-19 Vaccine When Available? | p-Value 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| n 3 (%) | n (%) | |||

| Age (mean, SD) 1 | 31.4 (13.4) | 30.7 (11.8) | 0.908 | |

| Sex | Male | 430 (38.6) | 685 (61.4) | <0.001 |

| Female | 550 (23.9) | 1749 (76.1) | ||

| Educational level 2 | High school or less | 86 (24.0) | 273 (76.0) | <0.001 |

| Undergraduate | 696 (27.2) | 1866 (72.8) | ||

| Postgraduate | 198 (40.2) | 295 (59.8) | ||

| History of chronic disease | Yes | 125 (34.6) | 236 (65.4) | 0.009 |

| No | 855 (28.0) | 2198 (72.0) | ||

| Experience of COVID-19 in self or family | Yes | 384 (28.3) | 971 (71.7) | 0.701 |

| No | 596 (28.9) | 1463 (71.1) | ||

| Country of Residence | Jordan | Kuwait | p-Value 3 | Saudi Arabia | Others 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conspiracy Belief and Attitude Items | n 2 (%) | n (%) | (Jordan vs. Kuwait) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| What is your belief about the origin of the current coronavirus in humans? | Natural | 902 (41.5) | 272 (35.3) | 0.002 | 53 (34.4) | 156 (49.4) |

| Man-made | 1271 (58.5) | 499 (64.7) | 101 (65.6) | 160 (50.6) | ||

| Do you think the current coronavirus was man-made to force everyone to get vaccinated? | Yes | 833 (38.3) | 373 (48.4) | <0.001 | 73 (47.4) | 97 (30.7) |

| No | 1340 (61.7) | 398 (51.6) | 81 (52.6) | 219 (69.3) | ||

| Will you get the coronavirus vaccine when available? | Yes | 618 (28.4) | 182 (23.6) | 0.010 | 49 (31.8) | 131 (41.5) |

| No | 1555 (71.6) | 589 (76.4) | 105 (68.2) | 185 (58.5) | ||

| Have you had or are you going to have the influenza vaccine? | Yes | 643 (29.6) | 246 (31.9) | 0.229 | 47 (30.5) | 120 (38.0) |

| No | 1530 (70.4) | 525 (68.1) | 107 (69.5) | 196 (62.0) | ||

| Do you oppose vaccination altogether? | Yes | 706 (32.5) | 279 (36.2) | 0.062 | 58 (37.7) | 69 (21.8) |

| No | 1467 (67.5) | 492 (63.8) | 96 (62.3) | 247 (78.2) | ||

| Do you think that coronavirus vaccine will be a way of implanting people with microchips to control humans? | Yes | 604 (27.8) | 247 (32.0) | 0.026 | 34 (22.1) | 62 (19.6) |

| No | 1569 (72.2) | 524 (68.0) | 120 (77.9) | 254 (80.4) | ||

| COVID-19 vaccines will lead to infertility 1 | Yes | 504 (23.2) | 212 (27.5) | 0.017 | 32 (20.8) | 52 (16.5) |

| No | 1669 (76.8) | 559 (72.5) | 122 (79.2) | 264 (83.5) | ||

| Do you think it is acceptable for the government to force everyone to get coronavirus vaccine? | Yes | 410 (18.9) | 126 (16.3) | 0.118 | 28 (18.2) | 63 (19.9) |

| No | 1763 (81.1) | 645 (83.7) | 126 (81.8) | 253 (80.1) |

| Factor | Odds Ratio (95% CI) 2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 origin (natural vs. man-made) 1 | 0.47 (0.38–0.57) | <0.001 |

| COVID-19 is man-made to force people to get the vaccine? (yes vs. no) | 1.89 (1.46–2.43) | <0.001 |

| COVID-19 vaccine will be used to implant microchips to humans? (yes vs. no) | 2.39 (1.72–3.30) | <0.001 |

| COVID-19 vaccine causes infertility? (yes vs. no) | 2.73 (1.90–3.93) | <0.001 |

| Are you against vaccination in general? (yes vs. no) | 9.26 (6.60–12.99) | <0.001 |

| Covariates | ||

| Age category | 1.01 (0.93–1.11) | 0.762 |

| Sex | 1.54 (1.28–1.85) | <0.001 |

| Country of residence | 0.94 (0.90–0.98) | 0.005 |

| Educational level | 0.78 (0.64–0.94) | 0.010 |

| History of chronic disease | 1.55 (1.15–2.09) | 0.004 |

| Self or family experience of COVID-19 | 0.88 (0.74–1.06) | 0.178 |

| Characteristic | Main Source of Information about COVID-19 Vaccines | TV Programs and News Releases | Social Media Platforms | Medical Doctors, Scientists and Scientific Journals | YouTube | p-Value 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n 4 (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Age category based on quartiles 1 | 16–21 years | 307 (31.0) | 337 (34.1) | 320 (32.4) | 25 (2.5) | <0.001 |

| 22–26 years | 199 (25.4) | 269 (34.3) | 304 (38.8) | 12 (1.5) | ||

| 27–39 years | 262 (32.8) | 222 (27.8) | 299 (37.5) | 15 (1.9) | ||

| 40 years or older | 315 (37.4) | 201 (23.8) | 320 (38.0) | 7 (0.8) | ||

| Sex | Male | 303 (27.2) | 310 (27.8) | 481 (43.1) | 21 (1.9) | <0.001 |

| Female | 780 (27.2) | 719 (31.3) | 762 (33.1) | 38 (1.7) | ||

| Country of residence 2 | Jordan | 756 (34.8) | 581 (26.7) | 804 (37.0) | 32 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Kuwait | 193 (25.0) | 304 (39.4) | 257 (33.3) | 17 (2.2) | ||

| Saudi Arabia | 53 (34.4) | 45 (29.2) | 53 (34.4) | 3 (1.9) | ||

| Others | 81 (25.6) | 99 (31.3) | 129 (40.8) | 7 (2.2) | ||

| Educational level 3 | High school or less | 108 (30.1) | 148 (41.2) | 89 (24.8) | 14 (3.9) | <0.001 |

| Undergraduate | 839 (32.7) | 809 (31.6) | 875 (34.2) | 39 (1.5) | ||

| Postgraduate | 136 (27.6) | 72 (14.6) | 279 (56.6) | 6 (1.2) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sallam, M.; Dababseh, D.; Eid, H.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; Al-Haidar, A.; Taim, D.; Yaseen, A.; Ababneh, N.A.; Bakri, F.G.; Mahafzah, A. High Rates of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Association with Conspiracy Beliefs: A Study in Jordan and Kuwait among Other Arab Countries. Vaccines 2021, 9, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9010042

Sallam M, Dababseh D, Eid H, Al-Mahzoum K, Al-Haidar A, Taim D, Yaseen A, Ababneh NA, Bakri FG, Mahafzah A. High Rates of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Association with Conspiracy Beliefs: A Study in Jordan and Kuwait among Other Arab Countries. Vaccines. 2021; 9(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleSallam, Malik, Deema Dababseh, Huda Eid, Kholoud Al-Mahzoum, Ayat Al-Haidar, Duaa Taim, Alaa Yaseen, Nidaa A. Ababneh, Faris G. Bakri, and Azmi Mahafzah. 2021. "High Rates of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Association with Conspiracy Beliefs: A Study in Jordan and Kuwait among Other Arab Countries" Vaccines 9, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9010042

APA StyleSallam, M., Dababseh, D., Eid, H., Al-Mahzoum, K., Al-Haidar, A., Taim, D., Yaseen, A., Ababneh, N. A., Bakri, F. G., & Mahafzah, A. (2021). High Rates of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Association with Conspiracy Beliefs: A Study in Jordan and Kuwait among Other Arab Countries. Vaccines, 9(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9010042