Abstract

Ruminants produce considerable amounts of methane during their digestive process, which makes the livestock industry as one of the largest sources of anthropogenic greenhouse gases. To tackle this situation, several solutions have been proposed, including vaccination of ruminants against microorganisms responsible for methane synthesis in the rumen. In this review, we summarize the research done on this topic and describe the state of the art of this strategy. The different steps implied in this approach are described: experimental design, animal model (species, age), antigen (whole cells, cell parts, recombinant proteins, peptides), adjuvant (Freund’s, Montanide, saponin, among others), vaccination schedule (booster intervals and numbers) and measurements of treatment success (immunoglobulin titers and/or effects on methanogens and methane production). Highlighting both the advances made and knowledge gaps in the use of vaccines to inhibit ruminant methanogen activity, this research review opens the door to future studies. This will enable improvements in the methodology and systemic approaches so as to ensure the success of this proposal for the sustainable mitigation of methane emission.

1. Introduction

Methane (CH4) is one of the main greenhouse gases; its negative effect on global warming is 21 times greater than that of carbon dioxide (CO2) [1]. Moreover, livestock-keeping is the human activity that generates most CH4, since ruminants emit large amounts in their digestive processes. This gas is formed in the ruminant forestomach (rumen) by methanogenic archaea [2]. During normal rumen function, plant material is degraded to produce volatile fatty acids, ammonia, hydrogen (H2), and CO2. Rumen methanogens principally consume H2 to reduce CO2 to CH4 [3]. Cattle, buffalo, and small ruminants release the equivalent of 2448 million tons of CO2 from both enteric processes and manure fermentation [4]. Within the farm environment, enteric fermentation is the most important source of CH4 emissions [5]. Thus, enteric CH4 generated in the gastrointestinal tracts of livestock is the single largest source of anthropogenic CH4 [6]. In the rumen, numerous prokaryotic (bacteria and archaea) and eukaryotic microorganisms (protozoa and fungi) work together to degrade the feedstuff consumed by the host ruminant [7]. In fact, on a well-managed confinement farm, enteric fermentation contributes about 45% of the total emission of greenhouse gases by the whole system. On more extensive grazing farms, these greenhouse-gas emissions could be even higher. For example, increased milk production has a positive correlation with CH4 emission [8]. Given that the livestock sector is one of the fastest-growing parts of the worldwide agricultural economy [9], the demand for milk and dairy products is expected to increase in coming decades, and thus so too are the CH4 emissions. It is therefore of utmost importance to find ways to mitigate the CH4 emissions from enteric fermentation. Mitigation approaches targeted at reducing CH4 must consider their effects on both enteric and manure fermentation, which account for approximately 90% and 10% of CH4 emissions, respectively [6]. Common approaches to reduce CH4 emissions in ruminants include dietary manipulation, drugs to reduce or control the quantity of methanogenic microorganisms in the gut, and/or vaccination. However, current strategies to inhibit methanogen activities in the rumen typically fail or have limited success due to low efficacy, poor selectivity, microorganism resistance, toxicity, or side effects of the compounds or drugs in the host species [3]. Dietary modification is the most-used strategy to reduce CH4 in ruminants, taking into account that different concentrates, subproducts, and/or forage combinations can reduce the quantity of CH4 production from the rumen [10,11,12], e.g., Goetsch [13] theorized that plant secondary metabolites could decrease CH4 emission, permitting the use of H2 to increase propionate production.

The control of animal diseases utilizes several strategies. Vaccines are one of the most important approaches, particularly on livestock farms [14]. The use of vaccines in these production sectors is increasing every year, especially for zoonotic diseases and those with significant effects on international trade [15]. However, concern regarding climate change has also increased dramatically. Reduction of emissions could therefore become economically attractive in the near future, making it viable to produce and market vaccines to mitigate climate change. This review attempts to clarify the state of the art of vaccination as a possible method for CH4 mitigation in ruminants.

2. The Rumen Microbiota

The rumen functions as a “fermentation chamber”, maintaining the right environment to host a wide community of microbes able to digest lignocellulosic polymers, the main constituent of the ruminant diet. The diet defines the microbial balance in the rumen, and consequently CH4 production [16]. An anaerobic atmosphere is maintained, with constant temperature and acidity [17]. Under these conditions, diverse microbes thrive and complex relationships are built between them, including symbiosis, consortia, cross-feeding, etc. [18,19,20]. Together they are able to process plant polysaccharides, which are otherwise indigestible for ruminants [21,22]. These polymers are broken down into products that will serve as nutrients for the animal, such as the volatile fatty acids acetate, propionate, and butyrate [23]. The rumen microbiota also serves other functions like detoxifying substances such as urea and protecting the host from harmful organisms like parasites and pathogens [24,25]. On the other hand, due to their fermentation activity, they generate byproducts such as CO2 or the gas of our concern: CH4 [26].

The main source of CH4 in the rumen is the hydrogenotrophic pathway [27], which is briefly explained as follows. During rumen fermentation, H2 is released by various microorganisms from the reducing equivalents in the process of glycolysis and pyruvate oxidative decarboxylation to acetyl CoA. The dissolved H2 is transferred between microorganisms in the rumen [28] and can be used by particular microbes in a number of ways, including the reduction of compounds such as fumarate, sulfate, nitrate, or nitrite, or other biochemical reactions such as reductive acetogenesis or hydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids. However, the main H2 sink is CH4 generation by methanogens [29,30] in a chemical reaction involving CO2 [31]. A higher amount of dissolved H2 in the rumen means an increase in CH4 production [32], and inhibition of methanogen activity is linked to a decrease in CH4 production and an increase in the amount of H2 [33]. In addition to the hydrogenotrophic pathway, other metabolic routes for CH4 production in the rumen have been described. Some methanogens use the formate remaining from the acetyl-CoA pathway, and, much less commonly, CH4 is produced via the methylotrophic pathway (from methyl groups and a certain amount of H2) and the acetoclastic pathway (using acetate) [31,34].

It has been suggested that changes in the composition of the microbial communities hosted in the rumen are associated with alterations in CH4 production [35]. To understand the process of CH4 production, it is necessary to gain insight into this community, which comprises a variety of anaerobic organisms including bacteria, archaea, protozoa, anaerobic fungi, mycoplasmas, and viruses [36,37]. Newborn ruminants have no rumen microorganisms at birth, but they acquire them in their first days of life, during the lactation period [38,39]. First, bacteria and archaea are established in the rumen, even before ingestion of solid foods [40]. Shortly afterwards, anaerobic fungi appear, and finally ciliate protozoa, the group that takes longest to stabilize even after weaning [41]. After the microbiome is established, it is thought to remain stable throughout the life of the ruminant [42,43], although recent studies have challenged this [44]. There is controversy regarding the factors that affect this microbiota; many have been mentioned in the literature, including diet, animal age, antibiotics, animal health, location, season, and host [37,41,45].

The most abundant microbes in biomass terms are bacteria, which are also highly diverse [41]. Their most common phyla are Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria [46]. Although bacteria in the rumen are not direct CH4 producers, differences in bacterial community structure are associated with these gas emissions. Lower CH4 production is associated with higher numbers of species that produce propionate (Quinella ovalis), lactate, and succinate (Fibrobacter spp.) [47], and higher amounts of certain genera of Proteobacteria phylum [46]. On the other hand, higher methane production is associated with greater numbers of species that are known to produce H2 in large amounts, e.g., Ruminococcus, Ruminococcaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Catabacteriaceae, Coprococcus and other Clostridiales, Prevotella, and other Bacteroidales and Alphaproteobacteria [47].

Archaea represent about 0.3 to 3% of the rumen microbiome, and they are also less diverse, with 10 main taxa [48,49,50]. Most (92.3%) are methanogenic, and are responsible for all CH4 production in the rumen [51]. Most methanogens belong to four orders: Methanobacteriales, Methanomicrobiales, Methanosarcinales, and one uncultured group called either Rumen cluster C (RCC), Thermoplasmatales-affiliated lineage C (TALC), or Methanoplasmatales [49,52]. The order Methanobacteriales is the most common in the rumen and comprises three major genera: Methanobrevibacter (which makes up 60% of the methanogens detected in the rumen [53], Methanobacterium, and Methanosphaera [18]. The first two are mainly hydrogenotrophic, although they can also use formate to produce CH4 [51], and Methanosphaera species are methylotrophs [54]. Concerning the other orders, Methanomicrobiales is represented mainly by the genus Methanomicrobium, which is found relatively abundantly in the rumen. The most common species belonging to this genus (M. mobile) is hydrogenotrophic [29]. The main member of the order Methanosarcinales is the genus Methanosarcina, which is methylotrophic and much less abundant than the aforementioned species [52]. The last order, the RCC, is barely known but could be methylotrophic as well [55]. Methanogens can be present in the rumen as free-living microbes, or associated with protozoa (10–20% [56]), either on their surface or endosymbiotically [46]. This portion is thought to produce from 9 to almost 40% of the CH4 originating in the rumen [57,58] and these microbes belong mostly to the hydrogenotrophic family Methanobacteriaceae [18].

Up to 12 genera of ciliate protozoa constitute an important part of the rumen microbiota, just behind bacteria in terms of biomass [37,46]. As stated before, there is a close relationship between methanogenic archaea and some protozoa [57], such as Entodinium, which is the dominant genus of protozoa in the rumen [59]. Protozoa favor archaeal populations, as they produce large amounts of H2 and provide physically protected support for methanogens [20]. However, the role of protozoa in the rumen is unclear. Their absence is associated with an outflow of microbial protein from the rumen, a drift in number and diversity in methanogen populations, and a decrease in CH4 production [39,60].

The last group worthy of mention are the anaerobic fungi, represented by nine genera [61], which may contribute up to 10% of the total rumen biomass [62]. Fungi produce H2, among other metabolic products [63], and fungi–archaea associations have been reported [61,64]. Despite this, the relationship between fungal abundance and CH4 production is not clear [46].

3. Antimethanogen Vaccines to Reduce CH4 in Ruminants

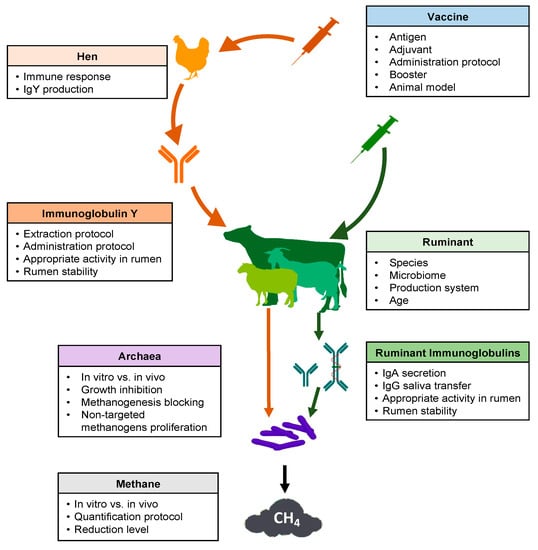

Several key points should be considered in the development of a successful strategy regarding the use of vaccines to reduce methane production from ruminal fermentation (Figure 1). Many articles and reviews have cited this possibility [26,30,65]. However, experimental research carried out between 1995 and 2020 was scarce in the consulted database (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of key points to consider for the use of vaccines to decrease methane emissions from ruminal fermentation.

Table 1.

Summary of experimental designs used in research into vaccination for mitigating methane in ruminants.

Several problems arose when comparing studies to assess the possibilities of using vaccines for this purpose. Concerning experimental design, as expected, the chosen antigens have developed along with the new technologies in the last 25 years, from whole methanogen cells to recombinant proteins from specific enzymes involved in CH4 production. Additionally, the different adjuvants and vaccination protocols used (Table 1) made it difficult to compare results. For example, Wedlock et al. [53] and Subharat et al. [66] both utilized recombinant glycosyl transferase protein (rGT2) as antigen, but the former with saponins as adjuvant and an intramuscular administration route in sheep as experimental animals, while the second was subcutaneous using Montanide in 5 month old calves. Additionally, those studies evaluated different immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, and IgY) and samples (blood, saliva, and rumen), or analyzed the effect on CH4 production using different approaches (in vitro, in vivo).

The most frequently used experimental animal model was the sheep, which was used in 8 out of 11 studies. One of the remaining studies used cattle and another used goats. Finally, a study proposed passive immunization producing antimethanogen Igs in hens. This made it difficult to compare research in order to draw solid conclusions. Patil et al. [67] assayed the immune response of sheep, cattle, and goats against four different serotypes of Foot and mouth disease virus at different times postvaccination. The cows showed higher levels of neutralizing antibodies than small ruminants for all tested virus serotypes. Lobato et al. [68] compared vaccination with recombinant toxin of Clostridium perfringens in the three common livestock ruminant species. In this study, sheep showed the highest antibody level, cattle the lowest, and goats intermediate. Moreira et al. [69] tested three recombinant vaccines against alpha, beta, and epsilon toxins of C. perfringens in the same three species. They found an interaction between antigens and species. There were no differences between species, except for with epsilon toxin. In the latter, cattle showed the highest antitoxin levels, with no differences between sheep and goats. In the same way, each species had a different response to each recombinant toxin, whereby all these animals had higher values against beta and lower against alpha toxin. Iqbal et al. [70] observed that ruminal bacterial, methanogen, and protozoal communities were different between cattle and buffalo, although Methanobrevibacter was the major genus for both species. These studies show that the animal model selected has an interaction with the antigen used. Obviously, small ruminants are cheaper animal models than cattle, and have fast growth and immune maturity. For these reasons, the use of goats and sheep in the early stages of vaccine development is more practical. However, the novel antigen must also be tested in the species for which it is being developed.

Additionally, animal age was another source of variation, with vaccinated sheep ranging from 3–5 months to 5 years old. It is well known that lambs are more susceptible to infectious diseases than adult sheep, and their immune resistance progressively increases during the first year of life [71]. According to Nguyen et al. [72], who compared 3 months old lambs with 2–5 years old sheep following a single intravenous injection of chicken erythrocytes, the adults had higher antibody titers than the young animals. This author affirmed that the antibody response of lambs reached the adult level at age 7–8 months and sex was not a variable that influenced this humoral response. Similarly, Watson et al. [71] assayed the antibody production of weaners and adult sheep against Brucella abortus. They reported that adults always showed a higher level of antibodies than weaners. Additionally, those authors found that both CD4+ and CD8+ in lymph and blood were higher in adults than in weaners, but B cells are lower in adult than in weaners’ lymph, with no difference in blood between ages. The authors suggested that B cells are not completely functional in younger animals, leading to the lower antibody response. Shu et al. [73] worked on a vaccine against Streptococcus bovis plus Freund’s adjuvant, reporting a lower antibody concentration than the previous studies in sheep. They tentatively attributed this difference to the age of the animals: 6 months old for Gill et al. [74], 1 year old for Shu et al. [75], and 2 years old in Shu et al. [73], where older animals showed higher antibody levels. However, methanogen vaccines in young animals are a very interesting target, because early programming of rumen microbiota using vaccines could be a better solution in comparison to adult animal vaccines. The rumen microbiota is established early in ruminant life, and it is possible to mold it through diet around weaning time, with a long-lasting effect [76]. De Barbieri et al. [77] found that rumen bacterial communities can change in both mothers and lambs after oral rumen inoculation in the neonatal period or first weeks of life.

The choice of the antigen to be inoculated is a key aspect for the development of a vaccine against methanogenic archaea in the rumen. Different approaches have been used to target methanogens (Table 1). The first strategy was to vaccinate the animals with whole cells of different archaeal species found in the rumen. In some studies, they specified that the methanogens had previously been killed by formaldehyde [78,79,80,81] or freeze-dried [82]. Baker and Perth [78] used a mix of ten strains of Methanobrevibacter ruminantium, M. arboriphilus, M. smithii, Methanobacter formicium, and Methanosarcina barkeri. Wright [79] checked 16S rDNA clone libraries from Australian sheep rumen samples. Based on that information, they chose one vaccine design with three strains of Methanobrevibacter spp. (two of them isolated in their lab in Australia) and another vaccine with seven strains from the four Methanobrevibacter species, Methanomicrobium mobile, M. barkeri, and Methanobacterium formicicum. Despite promising results by Wright [79], Clark et al. [80] tried to replicate them using the same mixture of three methanogens, alongside a combination of this mix with methanogenic material isolated from New Zealand sheep. Williams et al. [81] used whole cells of three Methanobrevibacter strains, Methanomicrobium mobile, and Methanosphaera stadtmaniae, which altogether comprised more than half of all the methanogen strains detected. Cook et al. [82] used Methanobrevibacter ruminantium, M. smithii, and Methanosphaera stadtmaniae, each in an independent hen group. They compared the in vitro effect of semipurified IgY and freeze-dried egg yolk from hens vaccinated with each archaeal species and a combination of the three.

Another strategy, derived from the first, was to use cell components as antigens. Wedlock et al. [83] compared the use of whole cells with cytoplasmic and wall-fraction proteins from M. ruminantium. In parallel, Leahy et al. [84] published the genome sequence of M. ruminantium; based on this sequence, these researchers chose nine peptides from extracellular regions of the cited archaea. Those peptides were synthesized and joined to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KHL), to be used as antigens. Later, Wedlock et al. [53] compared cytoplasmic and wall-fraction proteins with seven peptides from the extracellular domain of SecE and rGT2. The latter protein was used by Subharat et al. [66] and Subharat et al. [85] to vaccinate cattle and sheep. Zhang et al. [86] used the protein EhaF from M. ruminantium M1, which was one of the potential antigen candidates identified by Leahy et al. [84], with a key function in hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis.

Obviously, appropriate adjuvants must be selected for successful vaccine performance. This choice is based mainly on the animal species and antigen used. The experiments compiled in this review show how adjuvant use has developed over time, as new experience is acquired. Four out of ten ruminant experiments and the one with hens added complete/incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (FCA/FIA). Another two used saponins, and two recent studies used Montanide ISA. Shu et al. [73] compared the immune response to S. bovis vaccine with six different adjuvants (FCA, FIA, QuilA, dextran sulphate, alum, Gerbu). They found that FCA produced the largest quantity of blood antibodies in sheep. Using antimethanogen vaccines, two studies compared the efficacy of different adjuvants. Subharat et al. [85] contrasted four adjuvants (saponin, chitosan, lipid nanoparticles, and Montanide ISA). They reported that Montanide ISA61 produced the most IgG and IgA in saliva and serum. Subharat et al. [66] had previously affirmed that this Montanide with and without monophosphoryl lipid A was able to induce a strong humoral response in both IgA and IgG. The most usual administration route was subcutaneous in ruminants (six out of eleven); intramuscular and intradermal were the next most frequently applied in ruminants (both used in two experiments), and Baker and Perth [78] used intraperitoneal. The route in hens was intramuscular in the hen breast. Intramuscular and subcutaneous administration routes were the most common, although it has been suggested that intradermal injection could improve the mucosal response [87]. This is of great interest concerning the present topic. More research is necessary about the antigen–adjuvant–administration route combinations able to achieve a better combined response.

Regarding the booster and booster time, a significant variation in both number and period is shown in Table 1. Of the vaccination schedules, the most frequently used was one booster (six out of twelve studies) between 21 and 42 days postprimary, followed by two boosters (three out of twelve). The second vaccination given by Wright et al. [79] was not considered a booster because those authors decided to administer it when they observed low antibody levels, and neither was the third vaccination by Subharat et al. [85], since they tested only one group of animals to determine antibody longevity and the effect of boosting. Examining the results, administration of only one or two boosters appears insufficient to provide long-term immunity. For example, Williams et al. [81] reported that one booster 28 days after primary provided a peak at Day 55 after primary, but the titer decreased by Day 99. Using two boosters, Subharat et al. [85] achieved similar results, with a peak at Day 42 after the primary and the titer decreased until Day 133, when the animals were revaccinated and their specific antibodies titers increased. Those results indicate that a booster is necessary to reinforce antibody secretion. None of the other available studies elucidated the issue in this sense, despite this being a very important piece of knowledge to support this procedure for CH4 mitigation.

The time of sample collection to evaluate the immune response was another source of variation. Some authors decided to take only one sample after vaccination to quantify the specific antibodies [83,86], and this did not permit assessment of the specific antibodies’ secretion curves. Therefore, it is not possible to elucidate whether the curves were in their increasing, peak, or decreasing phases. In other studies, which measured immunoglobulins (Igs), the sampling time allowed analysis of the curve and also of the different phases of the antibody curves. Lobato et al. [68] tested a toxin vaccine on sheep, goats, and cattle with a booster on Day 28 after the primary. They reported that no antitoxin antibodies were detected on Day 0. On Day 42, 40% of goats, 60% of sheep, and 80% of cattle had titers lower than 1 IU/mL. On Day 56, all animals had titers equal to or higher than 5.8 IU/mL; sheep had the highest values, followed by goats and cattle.

4. Immunoglobulin Production, Saliva Secretion, and Activity in Rumen

In general, the immune response in the mucosa is mediated by mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue. However, no organized lymphoid tissue can be found in the rumen epithelium, and saliva has been suggested to be the main vehicle for introducing Igs into the rumen [40]. The efficacy of vaccine strategies to decrease CH4 production in the rumen depends on salivary Ig binding to the methanogen surface epitopes, which must inactivate, impede, or hinder CH4 production in the rumen [88]. Around 70% of the water contained in the rumen comes from saliva, which is the major source of antibodies in the rumen contents [74]. Previous authors affirmed that antibodies in serum are an important source of these immune proteins. After the stimulation of antibody production by vaccine, the Ig secretion (mainly IgA and IgG) in saliva is the second bottleneck in mitigation of CH4 through vaccination, due to limited IgG transfer from blood to saliva.

Table 1 and Table 2 show that eight of twelve trials measured Igs. All eight measured IgG in blood, seven in saliva, and five in rumen liquor. Only three, three, and one analyzed the mucosal secretory IgA in blood, saliva and rumen liquor, respectively. All trials achieved specific Ig production with different protocols, antigens, and adjuvants. These studies were difficult to compare, because most expressed antibody results as titers against the antigens used, but only a few of them offered results in absolute values as mg/mL. Wright et al. [79] reported the highest levels of antibodies before re-vaccinating animals 153 days after the primary vaccine. Other researchers achieved higher Ig levels with one booster (21 or 28 days after primary) or two (21 and 42 days after primary). The peaks in IgG and IgA were at similar times and the results showed the most IgG in blood, but IgA was higher in the saliva and rumen. When Leahy et al. [84] tested nine vaccines with peptides of M. ruminantium M1, they reported all peptides to be antigenic. It is noteworthy that the sheep attained the maximum antibody titers at different times, depending on the peptides. These were four out of nine on Day 42, with two boosters at 14 and 28 days after primary; then another four on Day 84, with four boosters 14, 28, 56 and 70 days after the primary. Finally, one group of animals reached the maximum on Day 98 after receiving five boosters on Days 14, 28, 56, 70, and 84 after the primary. Thus, these data show that different antigens can cause immune reactions at different times, depending on several factors.

Table 2.

Summary of immunoglobulin use in research into vaccination for methane mitigation in ruminants.

The substantial and continuous transfer or production of salivary antibodies will be crucial for the success of an antimethanogen vaccination strategy [66]. Assuming saliva is the principal source of ruminal antibodies, IgG transfer from blood and salivary IgA production are the main objectives of this approach. Secretory IgA has been shown to recognize 20% of commensal bacteria within the rumens of calves [89]. Fouhse et al. [90] hypothesized that if salivary IgA is a potential mechanism to determine commensal rumen microbiota, IgG may play a similar role. Six of the analyzed studies had between 279- and 800-fold more IgG in blood than in saliva. This points to a limited IgG transfer from blood to saliva. The other limitation of this antimethane approach is the survival of immunoglobulins in the rumen. In four of the studies, it was possible to calculate the IgG concentration ratio between saliva and rumen (3.88, 7.69, 84, and 209, in [65,80,84,85], respectively). This ratio was only possible to determine for IgA in two studies: 11.7 [85] and 26.11 [66]. However, IgA production in saliva is not comparable with IgG blood levels. There were contrasting results in these studies, i.e., Wright et al. [79] reported a higher titer of specific IgG in saliva than IgA, while Subharat et al. [85] found that 35% of total IgG was specific against methanogen protein, versus 42% of IgA. Using a rGT2 protein from M. ruminantium, Subharat et al. [66] reported a 17,416 and 30 μg/mL of IgG in blood and saliva, respectively, from vaccinated 5 month old male Holstein–Friesian calves. Similarly, the same group with the same antigen reported 19,931 and 41.7 μg/mL of IgG in blood and saliva, respectively, from vaccinated 6 month old lambs. Subharat et al. [66] commented that IgA is more resistant to rumen fluid than IgG, while both can maintain functionality for around 8 h in the rumen, as Williams et al. [59] also reported. However, the same group [85] described one year later that the IgG and IgA decreased by between 50% after 1.5 h incubation and 80–90% by 4 h. Therefore, antibodies induced by the vaccine maintain their activity in the rumen long enough to interact with antigen targets.

5. Vaccines and Rumen Populations/CH4 Emission

The rumen wall does not present glandular structures and is highly keratinized [91]; for this reason, it has been suggested that humoral immune responses in this organ are absent [74]. As previously mentioned, there is also no secretion of Igs in the rumen; they reach it through saliva [40]. The Igs play multiple roles, including complement fixing, opsonization, blocking, neutralization, and precipitation [92]. As there are no other components of the immune system in the rumen, such as complement or effector cells, the efficacy of the antibodies relies on their capacity to agglutinate and immobilize microorganisms, or to neutralize some essential structures of the microbes. The possibility of using vaccines to alter the microbial community of the rumen has been explored with different purposes. Gnanasampanthan [93] observed immobilization of rumen ciliates in vitro after adding immunized ewe antibodies. Williams et al. [59] targeted certain species of protozoa and recorded binding of antibodies to protozoa in vitro, and a reduction of their numbers. However, when they carried out in vivo trials, the vaccination had no effects on protozoan populations in the rumen. Shu et al. [94] reported milder symptoms (low ruminal pH and diarrhea) of ruminal acidosis in steer immunized with the principal bacteria responsible (Streptococcus bovis and Lactobacillus spp.). Sheep vaccinated with S. bovis also prevented symptoms of this condition [74,75]. Zhao et al. [95] observed less urease activity in cattle immunized with bacterial rumen urease compared to controls, in both in vivo and in vitro essays.

The ultimate aim of the studies covered in this review is for ruminants to produce less CH4. There is a wide array of techniques used to measure CH4 emissions by ruminants, differing in costs and suitability for the concrete purpose of study [31]. As shown in Table 3, seven out of eleven studies measured the CH4 production (three of them used in vitro and four in vivo techniques). Only three of them examined the effect of the vaccines on ruminal populations (two in vivo and one in vitro). Correspondence between results from in vitro and in vivo trials is questionable, and there are studies that both support and oppose this relation [96]. As an example, Bhatta et al. [97] measured CH4 production in goats and found a solid relationship between estimates from in vitro systems and the measures from open respiration chambers (in vivo systems). In contrast, Williams et al. [59] found a discrepancy between results in vitro (successful) and in vivo (unsuccessful) when they immunized sheep against rumen protozoa.

Table 3.

Effect of research into vaccinating ruminants on methane production.

Measuring CH4 using in vitro gas-production techniques is cheap, fast, and easy to replicate, because variation between samples is reduced compared to in vivo systems. As it is a simplification of real systems, it is recommended as a first approximation that should then be endorsed through experiments in animals [96]. All the in vitro studies showed some effect on CH4 production, despite different approaches to the problem. Baker and Perth [78] reported less CH4 emission (p < 0.018), when they compared ruminal fluid from the same sheep pre- and postvaccination. They also achieved a reduction in CH4 when comparing animals vaccinated with methanogen mix vs. adjuvant–PBS, with data both uncorrected (p < 0.018) and corrected for dry matter intake (p < 0.06). Cook et al. [82] purified chicken antibodies (IgYs) from three groups of hens immunized against three methanogens. Incubating ruminal fluid with these IgYs did not reduce CH4 emissions. However, a decrease in CH4 was reported when using total egg powder after 12 h incubation. This effect was stronger when applying a combination of eggs against three methanogens instead of using egg against a single strain. The reduction was no longer appreciable at 24 h of ruminal fluid incubation in any group. It is noteworthy that egg from non vaccinated hens caused a reduction in CH4 similarly to egg from immunized hens. So, in this particular experiment it seems that egg components other than IgYs caused a CH4 decrease. This can be explained because fatty acids (FAs) can inhibit CH4 production through various mechanisms; unsaturated FAs compete via H+ with methanogens [98], and long-chain FAs are directly toxic to methanogens [99]. Wedlock et al. [83] achieved an inhibition of CH4 production when growing M. ruminantium with the treated antisera of sheep vaccinated against whole cells, cytoplasmic fraction, or proteins derived from the cell wall. Additionally, they observed that the antisera were able to agglutinate cells of M. ruminantium, as well as to inhibit their growth, compared to pre-immune sera. However, the capacity to agglutinate the archaeal cells was not correlated to this inhibition of growth.

In vivo direct systems, which comprise open and closed respiration chambers, are very accurate, and the latter is widely considered the gold-standard method [100]. Nonetheless, they have some disadvantages: the animals are limited in their movements and feeding behavior, results differ from those gathered using free-range animals, and the infrastructure is expensive. In addition, measurements must be taken over short periods of time no longer than three days, and variations in gas production during that period have been repeatedly recorded [101]. In vivo indirect systems like the SF6 tracer are widely used alternative techniques, as they overcome some of the disadvantages of the respiration chambers. For example, the animal maintains its grazing habits and it is more economical [100]. However, Wright [79] did not find a clear relationship between SF6 and closed respiration chamber measurements. This reflects an inconsistency that has previously been reported [102] and is considered one of the main problems of this method [96].

Regarding the effect of vaccines on CH4 evaluated in vivo, Wright [79] used closed respiration chambers and was recorded a 7.7% (p < 0.51) reduction in CH4 production intake with a vaccine formulation that contained three strains of methanogens. Clark et al. [80] tested Wright’s three-methanogen vaccines, but found no reduction of CH4. Although these studies used the same antigens, several differences between them (animal age and location, booster, CH4 measuring technique) prevent comparison and a solid conclusion. Williams et al. [81] and Zhang et al. [86] reported no effects of vaccination on CH4 production (in sheep with a methanogen mix, and in goats with recombinant protein, respectively) using open-circuit chambers. Both studied the effects of the vaccines on rumen populations. Williams et al. [81] used real-time PCR to calculate numbers and checked clone library data to calculate diversity, but this group found no significant differences in total numbers of methanogens in the rumen of control and treated sheep. The authors suggested that some targeted methanogens could have been affected by the vaccine, as the diversity and methanogen compositions of the population were different in the different groups of sheep. Zhang et al. [86] did not detect alterations in either number or composition of methanogens. As a last remark, most of them measured CH4 emission around one month after vaccination or booster: 28 days [80], 28–42 days [59], and 34–42 days [81], except Zhang et al. [86], who measured it 15–17 days after the second booster (Table 1 and Table 3). This is an important source of variation, among others, which impedes comparison between these studies.

6. Conclusions

In summary, the possibility of applying vaccines to mitigate CH4 production from enteric fermentation in ruminants has been repeatedly suggested. Nevertheless, it is complicated to evaluate the real effectiveness of this strategy. Few studies have directly assessed the complete approach, i.e., from vaccination to enteric animal CH4 emission measurement. Furthermore, the great variety in methods is an obstacle in comparison of results from different studies in an appropriate and repeatable way. However, the strategy has been considered promising by many authors, and more research is needed to reach a rigorous conclusion on its feasibility, practical implementation, and sustainability. Various steps should be considered for future studies, such as antigenic capacity, Igs in saliva (IgG transfer and IgA production), action and stability of Igs in the rumen, and, finally, how to evaluate CH4 production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.P.d.l.L. and A.M.d.l.N.; methodology, V.B.-G., P.A.-C., S.G.-A., J.M.P.d.l.L., A.M.d.l.N.; investigation, V.B.-G., A.M.d.l.N.; visualization, V.B.-G., A.M.d.l.N.; writing—original draft preparation, V.B.-G., A.M.d.l.N.; writing—review and editing, V.B.-G., P.A.-C., S.G.-A., J.M.P.d.l.L., A.M.d.l.N.; supervision, J.M.P.d.l.L., A.M.d.l.N.; funding acquisition, J.M.P.d.l.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

A. Morales-delaNuez is currently funded by the Cabildo de Tenerife, under the TFinnova Programme supported by MEDI and FDCAN funds (project number 19-0231). The article was edited by Guido Jones, currently funded by the same institutions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kurniawan, T.; Budhi, Y.W.; Bindar, Y. Reverse flow reactor for catalytic oxidation of lean methane. World Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 2, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tapio, I.; Snelling, T.J.; Strozzi, F.; Wallace, R.J. The ruminal microbiome associated with methane emissions from ruminant livestock. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, S.C.; Kelly, W.J.; Ronimus, R.S.; Wedlock, N.; Altermann, E.; Attwood, G.T. Genome sequencing of rumen bacteria and archaea and its application to methane mitigation strategies. Animal 2013, 7 (Suppl. 2), 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opio, C.; Gerber, P.; Mottet, A.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G.; MacLeod, M.; Vellinga, T.; Henderson, B.; Steinfeld, H. Animal Production and Health Division: A Global Life Cycle Assessment Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Ruminant Supply Chains; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2013; ISBN 9789251079454. [Google Scholar]

- Rotz, C.A. Modeling greenhouse gas emissions from dairy farms. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 6675–6690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapp, J.; Laur, G.; Vadas, P.; Weiss, W.; Tricarico, J. Invited review: Enteric methane in dairy cattle production: Quantifying the opportunities and impact of reducing emissions. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 3231–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Elekwachi, C.O.; Jiao, J.; Wang, M.; Tang, S.; Zhou, C.; Tan, Z.; Forster, R.J. Investigation and manipulation of metabolically active methanogen community composition during rumen development in black goats OPEN. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, P.; Vellinga, T.; Opio, C.; Steinfeld, H. Productivity gains and greenhouse gas emissions intensity in dairy systems. Livest. Sci. 2011, 139, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Livestock in the Balance: The State of Food and Agriculture; FAO, Ed.; Communication Division, FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009; ISBN 978-92-5-106215-9. [Google Scholar]

- Puchala, R.; LeShure, S.; Gipson, T.A.; Tesfai, K.; Flythe, M.D.; Goetsch, A.L. Effects of different levels of lespedeza and supplementation with monensin, coconut oil, or soybean oil on ruminal methane emission by mature Boer goat wethers after different lengths of feeding. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2018, 46, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suha Uslu, O.; Kurt, O.; Kaya, E.; Kamalak, A. Effect of species on chemical composition, metabolizable energy, organic matter digestibility and methane production of some legume plants grown in Turkey. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2018, 46, 1158–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenco, J.M.; Maia, F.J.; Bittar, J.H.J.; Segers, J.R.; Tucker, J.J.; Campbell, B.T.; Stewart, R.L. Utilization of exogenous enzymes in beef cattle creep feeds. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2020, 48, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetsch, A.L. Recent research of feeding practices and the nutrition of lactating dairy goats. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2019, 47, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldens, J.G.M.; Patel, J.R.; Chanter, N.; Ten Thij, G.J.; Gravendijck, M.; Schijns, V.E.J.C.; Langen, A.; Schetters, T.P.M. Veterinary vaccine development from an industrial perspective. Vet. J. 2008, 178, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.F.; Bellet, C.; Rushton, J. Using economic and social data to improve veterinary vaccine development: Learning lessons from human vaccinology. Vaccine 2019, 37, 3974–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medjekal, S.; Ghadbane, M.; Bodas, R.; Bousseboua, H.; López, S. Volatile fatty acids and methane production from browse species of Algerian arid and semi-arid areas. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2018, 46, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungate, R.E. The Rumen and Its Microbes, 1st ed.; Academic Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1966; ISBN 978-1-4832-3308-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, R.; Ziemer, C.J.; Stern, M.D.; Stahl, D.A. Taxon-specific associations between protozoal and methanogen populations in the rumen and a model rumen system. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1998, 26, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, S.; Kobayashi, Y. Fibrolytic rumen bacteria: Their ecology and functions. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 22, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, A.; de la Fuente, G.; Newbold, C.J. Study of methanogen communities associated with different rumen protozoal populations. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 90, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palackal, N.; Lyon, C.S.; Zaidi, S.; Luginbühl, P.; Dupree, P.; Goubet, F.; Macomber, J.L.; Short, J.M.; Hazlewood, G.P.; Robertson, D.E.; et al. A multifunctional hybrid glycosyl hydrolase discovered in an uncultured microbial consortium from ruminant gut. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 74, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, D.O.; Denman, S.E.; Mackie, R.I.; Morrison, M.; Rae, A.L.; Attwood, G.T.; McSweeney, C.S. Opportunities to improve fiber degradation in the rumen: Microbiology, ecology, and genomics. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 663–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerfeld, E.M.; Kohn, R.A. The role of thermodynamics in the control of ruminal fermentation. In Ruminant Physiology; Sejrsen, K., Hvelplund, T., Nielsen, M.O., Eds.; Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 55–86. ISBN 978-90-76998-64-0. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Gautam, S.K.; Verma, V.; Kumar, M.; Singh, B. Metagenomics in animal gastrointestinal ecosystem: Potential biotechnological prospects. Anaerobe 2008, 14, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, E.M.; Kmit, M.C.P.; Chiaramonte, J.B.; Rossmann, M.; Mendes, R. Ecological aspects on rumen microbiome. In Diversity and Benefits of Microorganisms from the Tropics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 367–389. ISBN 978-3-319-55804-2. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin, K.A.; Ungerfeld, E.M.; Eckard, R.J.; Wang, M. Review: Fifty years of research on rumen methanogenesis: Lessons learned and future challenges for mitigation. Animal 2020, 14, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.K. Enteric methane mitigation technologies for ruminant livestock: A synthesis of current research and future directions. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2012, 184, 1929–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittelmann, S.; Seedorf, H.; Walters, W.A.; Clemente, J.C.; Knight, R.; Gordon, J.I.; Janssen, P.H. Simultaneous amplicon sequencing to explore co-occurrence patterns of bacterial, archaeal and eukaryotic M microorganisms in rumen microbial communities. PLoS ONE 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hook, S.E.; Wright, A.D.G.; McBride, B.W. Methanogens: Methane producers of the rumen and mitigation strategies. Archaea 2010, 2010, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashr, Y. Abatement of methane production from ruminants: Trends in the manipulation of rumen fermentation. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 23, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; McSweeney, C.; Wright, A.D.G.; Bishop-Hurley, G.; Kalantar-zadeh, K. Measuring Methane Production from Ruminants. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Lingen, H.J.; Edwards, J.E.; Vaidya, J.D.; Van Gastelen, S.; Saccenti, E.; van den Bogert, B.; Bannink, A.; Smidt, H.; Plugge, C.M.; Dijkstra, J. Diurnal dynamics of gaseous and dissolved metabolites and microbiota composition in the bovine rumen. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Fernandez, G.; Denman, S.E.; Yang, C.; Cheung, J.; Mitsumori, M.; McSweeney, C.S. Methane inhibition alters the microbial community, hydrogen flow, and fermentation response in the rumen of cattle. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.M.; Tripathi, A.K.; Pandya, P.R.; Parnerkar, S.; Rank, D.N.; Kothari, R.K.; Joshi, C.G. Methanogen diversity in the rumen of Indian Surti buffalo (Bubalus bubalis), assessed by 16S rDNA analysis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2012, 92, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, P.H. Influence of hydrogen on rumen methane formation and fermentation balances through microbial growth kinetics and fermentation thermodynamics. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2010, 160, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Ossa, F. The rumen microbiome: Composition, abundance, diversity, and new investigative tools. Prof. Anim. Sci. 2014, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapio, I.; Fischer, D.; Blasco, L.; Tapio, M.; Wallace, R.J.; Bayat, A.R.; Ventto, L.; Kahala, M.; Negussie, E.; Shingfield, K.J.; et al. Taxon abundance, diversity, co-occurrence and network analysis of the ruminal microbiota in response to dietary changes in dairy cows. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e180260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonty, G.; Gouet, P.; Jouany, J.P.; Senaud, J. Establishment of the microflora and anaerobic fungi in the rumen of lambs. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1987, 133, 1835–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbold, C.J.; De la Fuente, G.; Belanche, A.; Ramos-Morales, E.; McEwan, N.R. The role of ciliate protozoa in the rumen. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R.; Abecia, L.; Newbold, C.J. Manipulating rumen microbiome and fermentation through interventions during early life: A review. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbold, C.J.; Ramos-Morales, E. Review: Ruminal microbiome and microbial metabolome: Effects of diet and ruminant host. Animal 2020, 14, S78–S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abecia, L.; Martín-García, A.I.; Martinez, G.; Newbold, C.J.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R. Nutritional intervention in early life to manipulate rumen microbial colonization and methane output by kid goats postweaning. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 4832–4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, P.J. Redundancy, resilience, and host specificity of the ruminal microbiota: Implications for engineering improved ruminal fermentations. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, T.; Bielak, A.; Doyle, E.; Kuhla, B. Variations in methane yield and microbial community profiles in the rumen of dairy cows as they pass through stages of first lactation. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 5102–5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, G.; Cox, F.; Ganesh, S.; Jonker, A.; Young, W.; Janssen, P.H.; Abecia, L.; Angarita, E.; Aravena, P.; Arenas, G.N.; et al. Rumen microbial community composition varies with diet and host, but a core microbiome is found across a wide geographical range. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, W.; Yang, C. Ruminal methane production: Associated microorganisms and the potential of applying hydrogen-utilizing bacteria for mitigation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 654, 1270–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittelmann, S.; Pinares-Patiño, C.S.; Seedorf, H.; Kirk, M.R.; Ganesh, S.; McEwan, J.C.; Janssen, P.H. Two different bacterial community types are linked with the low-methane emission trait in sheep. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagita, K.; Kamagata, Y.; Kawaharasaki, M.; Suzuki, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Minato, H. Phylogenetic analysis of methanogens in sheep rumen ecosystem and detection of methanomicrobium mobile by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2000, 64, 1737–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeyanathan, J.; Kirs, M.; Ronimus, R.S.; Hoskin, S.O.; Janssen, P.H. Methanogen community structure in the rumens of farmed sheep, cattle and red deer fed different diets. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2011, 76, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.; Park, T.; Kim, M.; Yu, Z. Rumen methanogens and mitigation of methane emission by anti-methanogenic compounds and substances. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Whitman, W.B. Metabolic, phylogenetic, and ecological diversity of the methanogenic archaea. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1125, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwood, G.T.; Altermann, E.; Kelly, W.J.; Leahy, S.C.; Zhang, L.; Morrison, M. Exploring rumen methanogen genomes to identify targets for methane mitigation strategies. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2011, 166–167, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedlock, D.N.; Janssen, P.H.; Leahy, S.C.; Shu, D.; Buddle, B.M. Progress in the development of vaccines against rumen methanogens. Animal 2013, 7 (Suppl. 2), 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.L.; Wolin, M.J. Methanosphaera stadtmaniae gen. nov., sp. nov.: A species that forms methane by reducing methanol with hydrogen. Arch. Microbiol. 1985, 141, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, M.; Schwab, C.; Borg Jensen, B.; Engberg, R.M.; Spang, A.; Canibe, N.; Højberg, O.; Milinovich, G.; Fragner, L.; Schleper, C.; et al. Methylotrophic methanogenic Thermoplasmata implicated in reduced methane emissions from bovine rumen. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumm, C.K.; Gijzen, H.J.; Vogels, G.D. Association of methanogenic bacteria with ovine rumen ciliates. Br. J. Nutr. 1982, 47, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finlay, B.J.; Esteban, G.; Clarke, K.J.; Williams, A.G.; Embley, T.M.; Hirt, R.P. Some rumen ciliates have endosymbiotic methanogens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1994, 117, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newbold, C.J.; Lassalas, B.; Jouany, J.P. The importance of methanogens associated with ciliate protozoa in ruminal methane production in vitro. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1995, 21, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, Y.J.; Rea, S.M.; Popovski, S.; Pimm, C.L.; Williams, A.J.; Toovey, A.F.; Skillman, L.C.; Wright, A.D.G. Reponses of sheep to a vaccination of entodinial or mixed rumen protozoal antigens to reduce rumen protozoal numbers. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyader, J.; Eugène, M.; Nozière, P.; Morgavi, D.P.; Doreau, M.; Martin, C. Influence of rumen protozoa on methane emission in ruminants: A meta-analysis approach. Animal 2014, 8, 1816–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, J.E.; Forster, R.J.; Callaghan, T.M.; Dollhofer, V.; Dagar, S.S.; Cheng, Y.; Chang, J.; Kittelmann, S.; Fliegerova, K.; Puniya, A.K.; et al. PCR and omics based techniques to study the diversity, ecology and biology of anaerobic fungi: Insights, challenges and opportunities. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, D.O.; Nagaraja, T.G.; Wright, A.D.G.; Callaway, T.R. Rumen microbiology: Leading the way in microbial ecology. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountfort, D.O. The rumen anaerobic fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1987, 46, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cheng, Y.F.; Edwards, J.E.; Allison, G.G.; Zhu, W.Y.; Theodorou, M.K. Diversity and activity of enriched ruminal cultures of anaerobic fungi and methanogens grown together on lignocellulose in consecutive batch culture. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 4821–4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, J.; Oldenbroek, J.K.; van Keulen, H.; Zwart, D. Criteria for sustainable livestock production: A proposal for implementation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1995, 53, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subharat, S.; Shu, D.; Zheng, T.; Buddle, B.M.; Janssen, P.H.; Luo, D.; Wedlock, D.N. Vaccination of cattle with a methanogen protein produces specific antibodies in the saliva which are stable in the rumen. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2015, 164, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, P.K.; Bayry, J.; Ramakrishna, C.; Hugar, B.; Misra, L.D.; Prabhudas, K.; Natarajan, C. Immune responses of sheep to quadrivalent double emulsion Foot-and-Mouth Disease vaccines: Rate of development of immunity and variations among other ruminants. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 4367–4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lobato, F.C.F.; Lima, C.G.R.D.; Assis, R.A.; Pires, P.S.; Silva, R.O.S.; Salvarani, F.M.; Carmo, A.O.; Contigli, C.; Kalapothakis, E. Potency against enterotoxemia of a recombinant Clostridium perfringens type D epsilon toxoid in ruminants. Vaccine 2010, 28, 6125–6127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, G.M.S.G.; Salvarani, F.M.; Da Cunha, C.E.P.; Mendonça, M.; Moreira, Â.N.; Gonçalves, L.A.; Pires, P.S.; Lobato, F.C.F.; Conceição, F.R. Immunogenicity of a trivalent recombinant vaccine against Clostridium perfringens alpha, beta, and epsilon toxins in farm ruminants. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.W.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Li, L.; Zou, C.; Huang, C.; Lin, B.; Wasim Iqbal, M. Comparative study of rumen fermentation and microbial community differences between water buffalo and Jersey cows under similar feeding conditions. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2018, 46, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.L.; Colditz, I.G.; Andrew, M.; Gill, H.S.; Altmann, K.G. Age-dependent immune response in Merino sheep. Res. Vet. Sci. 1994, 57, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.C. The immune response in sheep: Analysis of age, sex and genetic effects on the quantitative antibody response to chicken red blood cells. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1984, 5, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Q.; Bird, S.; Gill, H.; Duan, E.; Xu, Y.; Hillard, M.; Rowe, J. Antibody response in sheep following immunization with Streptococcus bovis in different adjuvants. Vet. Res. Commun. 2001, 25, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, H.S.; Shu, Q.; Leng, R.A. Immunization with Streptococcus bovis protects against lactic acidosis in sheep. Vaccine 2000, 18, 2541–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Q.; Hillard, M.A.; Bindon, B.M.; Duan, E.; Xu, Y.; Bird, S.H.; Rowe, J.B.; Oddy, V.H.; Gill, H.S. Effects of various adjuvants on efficacy of a vaccine against Streptococcus bovis and Lactobacillus spp. in cattle. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2000, 61, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R.; Macías, B.; Pinloche, E.; Newbold, C.J. The persistence of bacterial and methanogenic archaeal communities residing in the rumen of young lambs. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2010, 72, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Barbieri, I.; Hegarty, R.S.; Silveira, C.; Gulino, L.M.; Oddy, V.H.; Gilbert, R.A.; Klieve, A.V.; Ouwerkerk, D. Programming rumen bacterial communities in newborn Merino lambs. Small Rumin. Res. 2015, 129, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.K.; Perth, W. Method for Improving Utilization of Nutrients by Ruminant or Ruminant-Like Animals. U.S. Patent 6,036,950, 14 March 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, A. Reducing methane emissions in sheep by immunization against rumen methanogens. Vaccine 2004, 22, 3976–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, H.; Wright, A.-D.; Joblin, K.; Molano, G.; Cavanagh, A.; Peters, J. Field testing an Australian developed anti-methanogen vaccine in growing ewe lambs. In Proceedings of the Workshop on the Science of Atmospheric Trace Gases; Clarkson, T.S., Ed.; Science Communication, NIWA: Wellington, New Zealand, 2004; pp. 107–108. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Y.J.; Popovski, S.; Rea, S.M.; Skillman, L.C.; Toovey, A.F.; Northwood, K.S.; Wright, A.D.G. A vaccine against rumen methanogens can alter the composition of archaeal populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 1860–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, S.R.; Maiti, P.K.; Chaves, A.V.; Benchaar, C.; Beauchemin, K.A.; McAllister, T.A. Avian (IgY) anti-methanogen antibodies for reducing ruminal methane production: In vitro assessment of their effects. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 2008, 48, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedlock, D.N.; Pedersen, G.; Denis, M.; Buddle, B.M.; Dey, D.; Janssen, P.H. Development of a vaccine to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture: Vaccination of sheep with methanogen fractions induces antibodies that block methane production in vitro. N. Z. Vet. J. 2010, 58, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, S.C.; Kelly, W.J.; Altermann, E.; Ronimus, R.S.; Yeoman, C.J.; Pacheco, D.M.; Li, D.; Kong, Z.; McTavish, S.; Sang, C.; et al. The genome sequence of the rumen methanogen Methanobrevibacter ruminantium reveals new possibilities for controlling ruminant methane emissions. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subharat, S.; Shu, D.; Zheng, T.; Buddle, B.M.; Kaneko, K.; Hook, S.; Janssen, P.H.; Wedlock, D.N. Vaccination of sheep with a methanogen protein provides insight into levels of antibody in saliva needed to target ruminal methanogens. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Huang, X.; Xue, B.; Peng, Q.; Wang, Z.; Yan, T.; Wang, L. Immunization against rumen methanogenesis by vaccination with a new recombinant protein. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawan, A.; Jesse, F.F.A.; Idris, U.H.; Odhah, M.N.; Arsalan, M.; Muhammad, N.A.; Bhutto, K.R.; Peter, I.D.; Abraham, G.A.; Wahid, A.H.; et al. Mucosal and systemic responses of immunogenic vaccines candidates against enteric Escherichia coli infections in ruminants: A review. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 117, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddle, B.M.; Denis, M.; Attwood, G.T.; Altermann, E.; Janssen, P.H.; Ronimus, R.S.; Pinares-Patiño, C.S.; Muetzel, S.; Neil Wedlock, D. Strategies to reduce methane emissions from farmed ruminants grazing on pasture. Vet. J. 2011, 188, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuruta, T.; Inoue, R.; Tsukahara, T.; Nakamoto, M.; Hara, H.; Ushida, K.; Yaima, T. Commensal bacteria coated by secretory immunoglobulin A and immunoglobulin G in the gastrointestinal tract of pigs and calves. Anim. Sci. J. 2012, 83, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouhse, J.M.; Smiegielski, L.; Tuplin, M.; Guan, L.L.; Willing, B.P. Host immune selection of rumen bacteria through salivary secretory IgA. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobson, M.J.; Brown, W.C.B.; Dobson, A.; Phillipson, A.T. A histological study of the organization of the rumen epithelium of sheep. Q. J. Exp. Physiol. Cogn. Med. Sci. 1956, 41, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.E. Bovine immunoglobulins: An augmented review. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1983, 4, 43–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanasampanthan, G. Immune Responses of Sheep to Rumen Ciliates and the Survival and Activity of Antibodies in the Rumen Fluid. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Q.; Gill, H.S.; Hennessy, D.W.; Leng, R.A.; Bird, S.H.; Rowe, J.B. Immunisation against lactic acidosis in cattle. Res. Vet. Sci. 1999, 67, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wang, J.; Zheng, N.; Bu, D.; Sun, P.; Yu, Z. Reducing microbial ureolytic activity in the rumen by immunization against urease therein. BMC Vet. Res. 2015, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storm, I.M.L.D.; Hellwing, A.L.F.; Nielsen, N.I.; Madsen, J. Methods for measuring and estimating methane emission from ruminants. Animals 2012, 2, 160–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, R.; Enishi, O.; Takusari, N.; Higuchi, K.; Nonaka, I.; Kurihara, M. Diet effects on methane production by goats and a comparison between measurement methodologies. J. Agric. Sci. 2008, 146, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, T.A.; Okine, E.K.; Mathison, G.W.; Cheng, K.J. Dietary, environmental and microbiological aspects of methane production in ruminants. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 1996, 76, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, C. The effects of fatty acids on pure cultures of rumen bacteria. J. Agric. Sci. 1973, 81, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.K. Recent advances in measurement and dietary mitigation of enteric methane emissions in ruminants. Front. Vet. Sci. 2016, 3, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorg, D.; Difford, G.F.; Mühlbach, S.; Kuhla, B.; Swalve, H.H.; Lassen, J.; Strabel, T.; Pszczola, M. Comparison of a laser methane detector with the GreenFeed and two breath analysers for on-farm measurements of methane emissions from dairy cows. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 153, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinares-Patiño, C.S.; Lassey, K.R.; Martin, R.J.; Molano, G.; Fernandez, M.; MacLean, S.; Sandoval, E.; Luo, D.; Clark, H. Assessment of the sulphur hexafluoride (SF6) tracer technique using respiration chambers for estimation of methane emissions from sheep. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2011, 166–167, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).