West Nile Virus: Epidemiology, Surveillance, and Prophylaxis with a Comparative Insight from Italy and Iran

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. WNV Lineages

1.2. Climate Changes

2. Methods

3. Molecular Biology of West Nile Virus

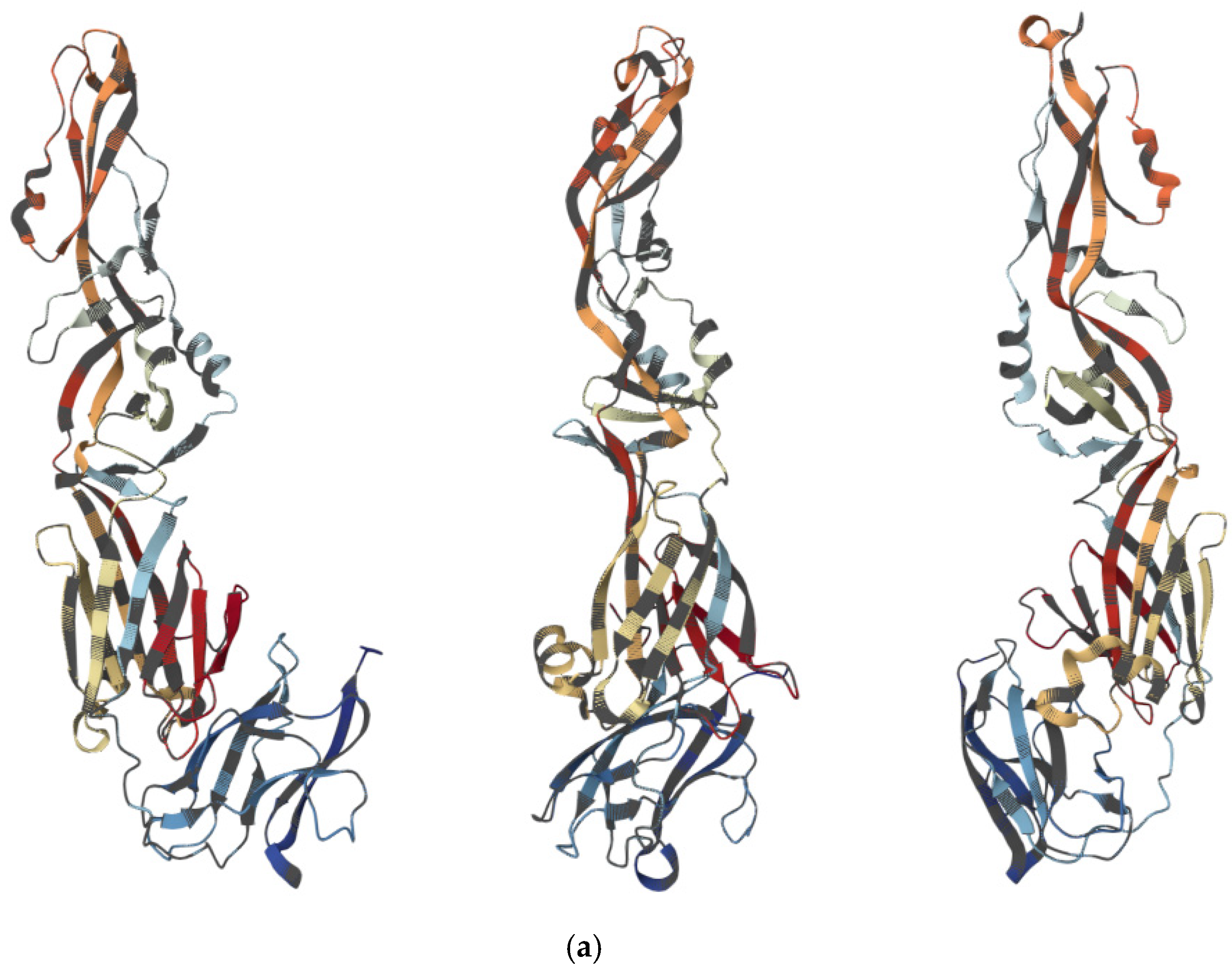

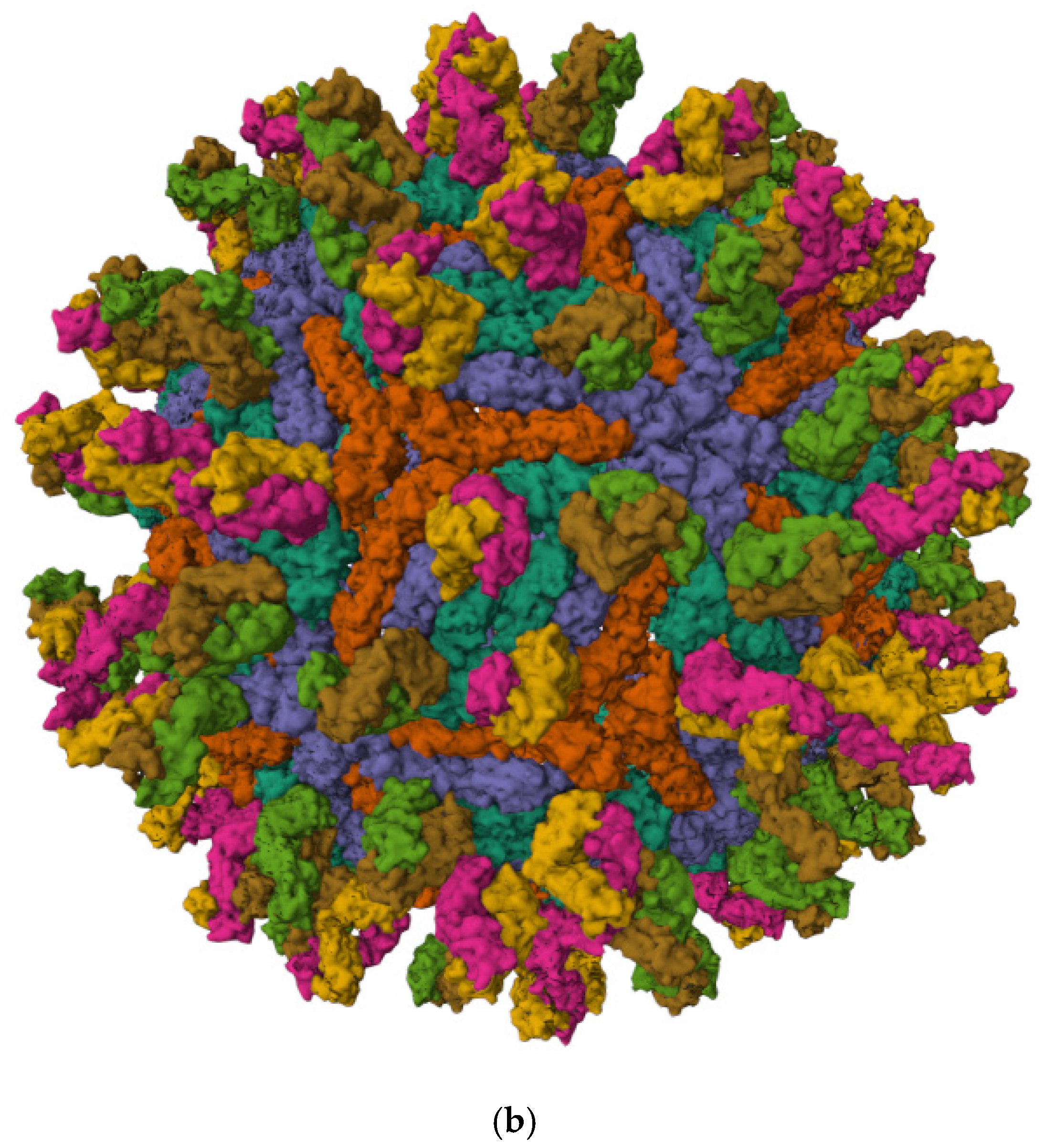

3.1. Viral Structure and Genome

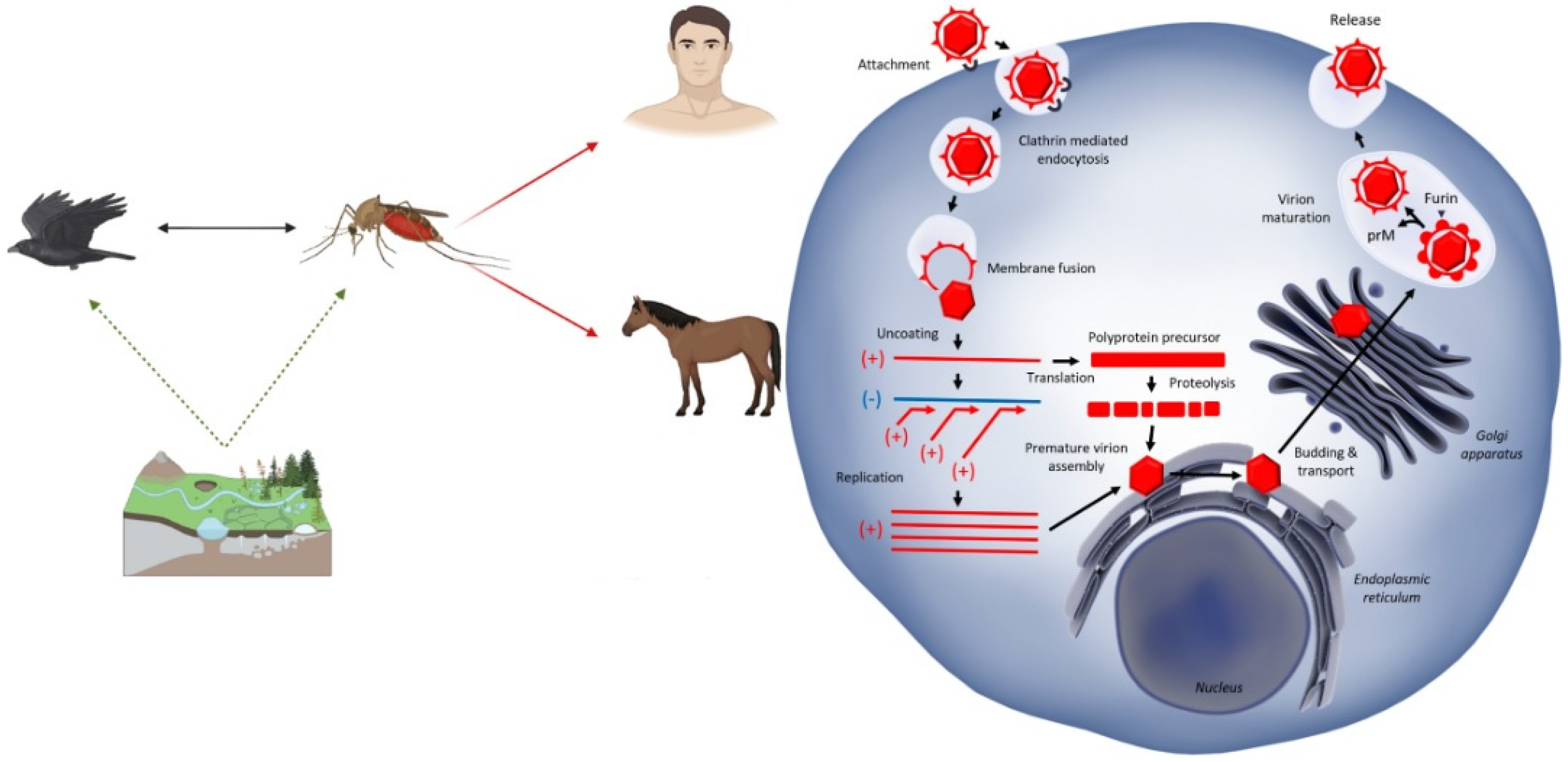

3.2. Life Cycle Within Hosts

3.3. Mechanisms of Replication and Immune Evasion

4. From Transmission to Disease

4.1. Role of Mosquito Vectors (With a Focus on Culex Species)

4.2. Zoonotic Transmission Cycles Involving Birds

4.3. Human Infection: Symptomatic vs. Asymptomatic Cases

4.4. Neurological Complications and Mortality Rates

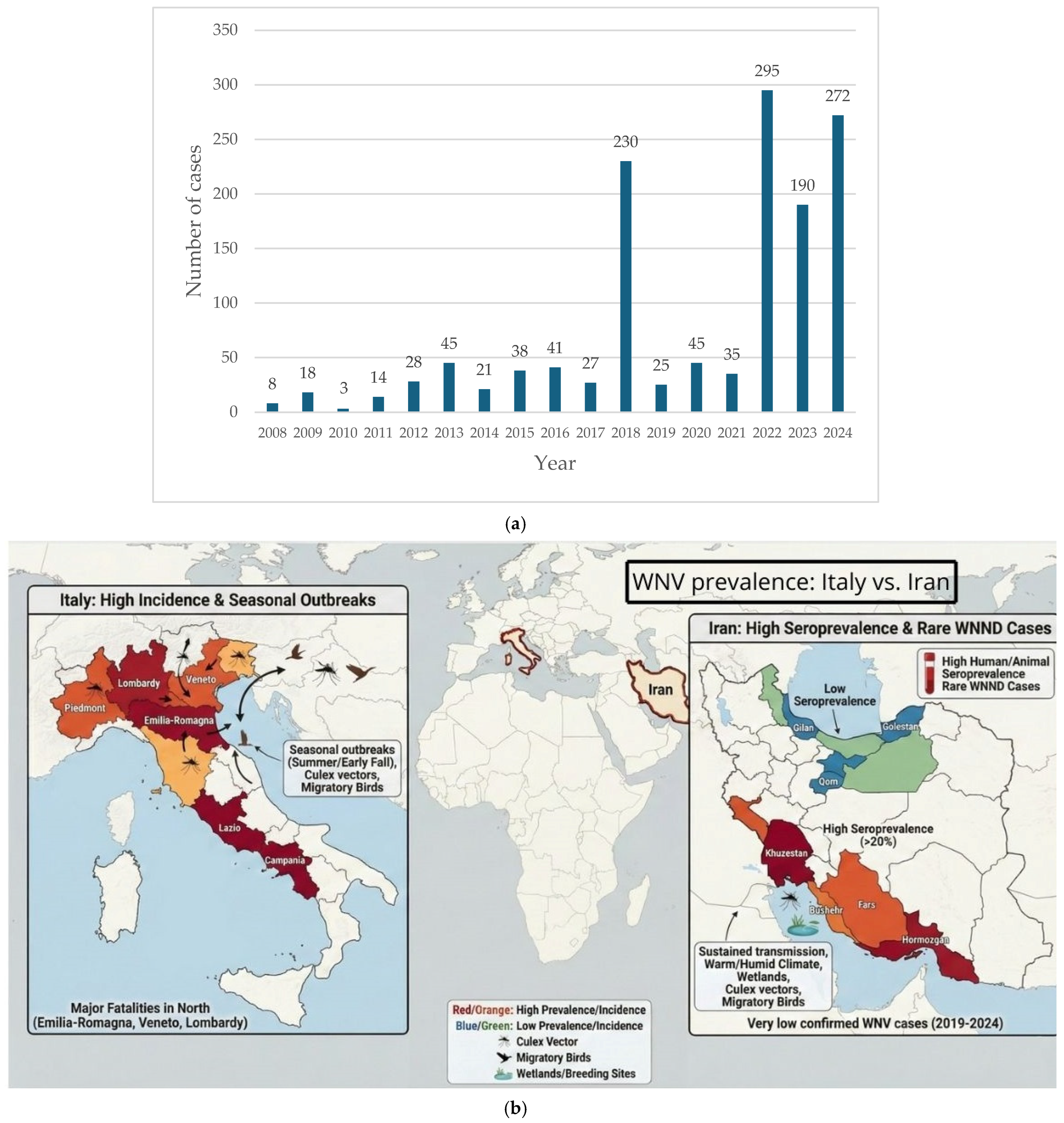

5. The Epidemiological Landscape: The Mediterranean and Middle East Overview

5.1. Case Study: Italy vs. Iran

5.2. National Health Strategies

5.2.1. Strategies Adopted in Italy

5.2.2. Strategies Adopted in Iran

5.3. Historical Outbreaks and Containment

5.3.1. The WNV Situation in Italy

5.3.2. The WNV Situation in Iran

6. Current Status of Vaccination and Therapeutic Efforts

6.1. Challenges in WNV Vaccine Development

6.2. WNV Vaccination Strategies

6.2.1. Vero-Derived Vaccines in Human Trials

6.2.2. Weakened WNV Vaccines

6.2.3. Chimeric WNV Vaccines

6.2.4. Viral Vector Vaccines

6.2.5. Existing Veterinary Vaccines and Implications for Public Health

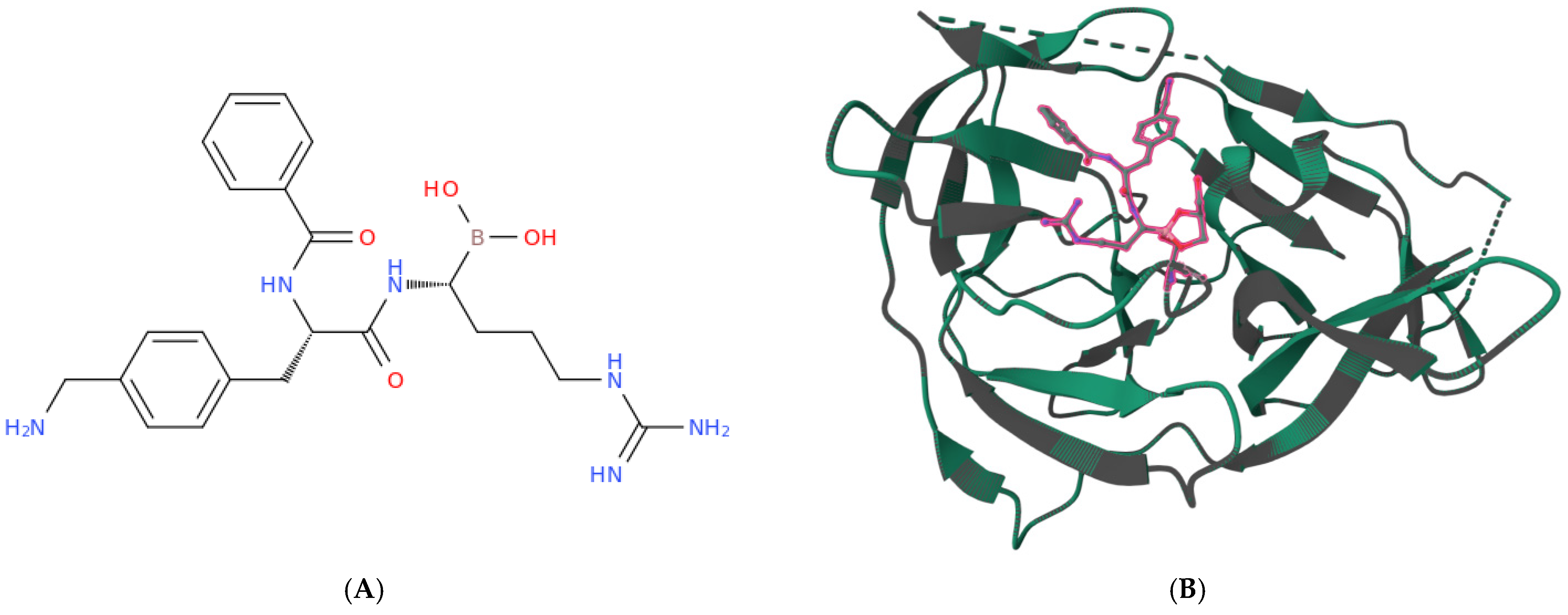

6.3. Potential Drugs for WNV Disease

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFP | Acute Flaccid Paralysis |

| C | Capsid Protein |

| DENV | Dengue Virus |

| DIVA | Differentiating Infected vs. Vaccinated Animals |

| ddRT PCR | Droplet Digital Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| E | Envelope Protein |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| G4 | G quadruplex |

| MVA | Modified Vaccinia Ankara |

| NAT | Nucleic Acid Testing |

| NS | Nonstructural Protein |

| ORF | Open Reading Frame |

| prM | Premembrane Protein |

| RdRp | RNA-dependent RNA Polymerase |

| TGN | Trans Golgi Network |

| UTR | Untranslated Region |

| VLP | Virus-like particle |

| WBE | Wastewater-Based Epidemiology |

| WNV | West Nile Virus |

| WNND | West Nile Neuroinvasive Disease |

| WNVD | West Nile Virus Disease |

| ZIKV | Zika Virus |

References

- Madere, F.S.; Andrade da Silva, A.V.; Okeze, E.; Tilley, E.; Grinev, A.; Konduru, K.; García, M.; Rios, M. Flavivirus infections and diagnostic challenges for dengue, West Nile and Zika Viruses. npj Viruses 2025, 3, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.G.; Bowen, J.R.; McDonald, C.E.; Pulendran, B.; Suthar, M.S. West Nile virus infection blocks inflammatory response and T cell costimulatory capacity of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00664-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.R.; Ismail, A.A.; Thergarajan, G.; Raju, C.S.; Yam, H.C.; Rishya, M.; Sekaran, S.D. Serological cross-reactivity among common flaviviruses. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 975398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curren, E.J.; Shankar, M.B.; Fischer, M.; Meltzer, M.I.; Erin Staples, J.; Gould, C.V. Cost-effectiveness and impact of a targeted age-and incidence-based West Nile virus vaccine strategy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 1565–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocabiyik, D.Z.; Álvarez, L.F.; Durigon, E.L.; Wrenger, C. West Nile virus-a re-emerging global threat: Recent advances in vaccines and drug discovery. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1568031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbert, S. West Nile virus vaccines–current situation and future directions. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 15, 2337–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palancı, H.S.; Gülmez, A.; Dik, I.; Bulut, O.; Ünal, B.; Öktem, İ.M.A.; Özbek, Ö.A. Evaluation of a commercial ELISA IgG antibody Kit for Orthoflavivirus nilense (West Nile Virus): Screening utility and comparison with virus neutralization test. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2025, 114, 117098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zulli, A.; Duong, D.; Shelden, B.; Bidwell, A.; Wolfe, M.K.; White, B.; Boehm, A.B. West Nile Virus (Orthoflavivirus nilense) RNA concentrations in wastewater solids at five wastewater treatment plants in the United States. PeerJ 2025, 13, e19748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhou, B.; Su, W.; Liu, W.; Qu, C.; Miao, Y.; Chen, C.; Ma, M.; Dai, B.; Wu, H. Wastewater-Based Monitoring of Dengue Fever at Community Level—Guangzhou City, Guangdong Province, China, May 2024. China CDC Wkly. 2025, 7, 1160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sims, N.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B. Future perspectives of wastewater-based epidemiology: Monitoring infectious disease spread and resistance to the community level. Environ. Int. 2020, 139, 105689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, C.G. West Nile virus: Uganda, 1937, to New York City, 1999. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 951, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.L.; Ross, T.M.; Evans, J.D. West nile virus. Clin. Lab. Med. 2010, 30, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, L.R.; Brault, A.C.; Nasci, R.S. West Nile virus: Review of the literature. Jama 2013, 310, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zittis, G.; Almazroui, M.; Alpert, P.; Ciais, P.; Cramer, W.; Dahdal, Y.; Fnais, M.; Francis, D.; Hadjinicolaou, P.; Howari, F. Climate change and weather extremes in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, e2021RG000762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somveille, M.; Manica, A.; Butchart, S.H.; Rodrigues, A.S. Mapping global diversity patterns for migratory birds. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.; Fernández de Marco, M.; Giovannini, A.; Ippoliti, C.; Danzetta, M.L.; Svartz, G.; Erster, O.; Groschup, M.H.; Ziegler, U.; Mirazimi, A. Emerging mosquito-borne threats and the response from European and Eastern Mediterranean countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baraiya, H.L.; Sirola, G.; Baroth, A.; Kumar, R.S. Tracking the long way around: Seasonal migration strategies, detours and spatial bottlenecks in common cranes wintering in western India. Anim. Biotelem. 2025, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammuri, G.; Alari Esposito, G.; De Paulis, M.; Pezzo, F.; Sforzi, A.; Monti, F. From Nest to Nest: High-Precision GPS-GSM Tracking Reveals Full Natal Dispersal Process in a First-Year Female Montagu’s Harrier Circus pygargus. Birds 2025, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegon, M.; Casale, F.; Mancuso, E.; Di Luca, M.; Severini, F.; Monaco, F.; Toma, L. New finding on a migratory bird, the fowl tick Argas (Persicargas) persicus (Oken, 1818), in Italy. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2025, 94, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Peruzzi, S.; Balzarini, F. Epidemiology of West Nile virus infections in humans, Italy, 2012–2020: A summary of available evidences. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinikar, S.; Shah-Hosseini, N.; Mostafavi, E.; Moradi, M.; Khakifirouz, S.; Jalali, T.; Goya, M.M.; Shirzadi, M.R.; Zainali, M.; Fooks, A.R. Seroprevalence of west nile virus in iran. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2013, 13, 586–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, J.S.; Jeggo, M. The one health approach—Why is it so important? Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 4, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filette, M.; Ulbert, S.; Diamond, M.S.; Sanders, N.N. Recent progress in West Nile virus diagnosis and vaccination. Vet. Res. 2012, 43, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donadieu, E.; Bahuon, C.; Lowenski, S.; Zientara, S.; Coulpier, M.; Lecollinet, S. Differential virulence and pathogenesis of West Nile viruses. Viruses 2013, 5, 2856–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehér, O.; Bakonyi, T.; Barna, M.; Nagy, A.; Takács, M.; Szenci, O.; Joó, K.; Sárdi, S.; Korbacska-Kutasi, O. Serum neutralising antibody titres against a lineage 2 neuroinvasive West Nile Virus strain in response to vaccination with an inactivated lineage 1 vaccine in a European endemic area. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2020, 227, 110087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaintoutis, S.C.; Diakakis, N.; Papanastassopoulou, M.; Banos, G.; Dovas, C.I. Evaluation of cross-protection of a lineage 1 West Nile virus inactivated vaccine against natural infections from a virulent lineage 2 strain in horses, under field conditions. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2015, 22, 1040–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorovitch, M.F.; Tuchynskaya, K.K.; Kruglov, Y.A.; Peunkov, N.S.; Mostipanova, G.F.; Kholodilov, I.S.; Ivanova, A.L.; Fedina, M.P.; Gmyl, L.V.; Morozkin, E.S. An Inactivated West Nile Virus Vaccine Candidate Based on the Lineage 2 Strain. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadnejad, F.; Otarod, V.; Fathnia, A.; Ahmadabadi, A.; Fallah, M.H.; Zavareh, A.; Miandehi, N.; Durand, B.; Sabatier, P. Impact of climate and environmental factors on West Nile virus circulation in Iran. J. Arthropod-Borne Dis. 2016, 10, 315. [Google Scholar]

- Paquette, S.-J.; Simon, A.Y.; Xiii, A.; Kobinger, G.P.; Shahhosseini, N. Medically significant vector-borne viral diseases in Iran. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidecke, J.; Lavarello Schettini, A.; Rocklöv, J. West Nile virus eco-epidemiology and climate change. PLoS Clim. 2023, 2, e0000129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzon, A.; Granata, M.; Verzelloni, P.; Tommasi, L.; Palandri, L.; Malavolti, M.; Bargellini, A.; Righi, E.; Vinceti, M.; Paduano, S. Effect of Climate Change on West Nile Virus Transmission in Italy: A Systematic Review. Public Health Rev. 2025, 46, 1607444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingione, M.; Branda, F.; Maruotti, A.; Ciccozzi, M.; Mazzoli, S. Monitoring the West Nile virus outbreaks in Italy using open access data. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, Z.; Rocklöv, J.; Wallin, J.; Abiri, N.; Sewe, M.O.; Sjödin, H.; Semenza, J.C. Artificial intelligence to predict West Nile virus outbreaks with eco-climatic drivers. Lancet Reg. Health–Eur. 2022, 17, 100370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, S.-U.; Bai, F. Introduction to West nile virus. In West Nile Virus: Methods and Protocols; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, W.C.; Soto-Acosta, R.; Bradrick, S.S.; Garcia-Blanco, M.A.; Ooi, E.E. The 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions of the flaviviral genome. Viruses 2017, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praveen, M. Characterizing the West Nile Virus’s polyprotein from nucleotide sequence to protein structure–Computational tools. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2024, 19, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chappell, K.; Stoermer, M.; Fairlie, D.; Young, P. West Nile Virus NS2B/NS3 protease as an antiviral target. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008, 15, 2771–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, G.L.; Marfin, A.A.; Lanciotti, R.S.; Gubler, D.J. West nile virus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2002, 2, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nybakken, G.E.; Nelson, C.A.; Chen, B.R.; Diamond, M.S.; Fremont, D.H. Crystal structure of the West Nile virus envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 11467–11474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, R.; Kar, K.; Anthony, K.; Gould, L.H.; Ledizet, M.; Fikrig, E.; Marasco, W.A.; Koski, R.A.; Modis, Y. Crystal structure of West Nile virus envelope glycoprotein reveals viral surface epitopes. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 11000–11008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenhuis-Zybert, I.A.; Moesker, B.; da Silva Voorham, J.M.; van der Ende-Metselaar, H.; Diamond, M.S.; Wilschut, J.; Smit, J.M. A fusion-loop antibody enhances the infectious properties of immature flavivirus particles. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 11800–11808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moesker, B.; Rodenhuis-Zybert, I.A.; Meijerhof, T.; Wilschut, J.; Smit, J.M. Characterization of the functional requirements of West Nile virus membrane fusion. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Kuhn, R.J.; Rossmann, M.G. A structural perspective of the flavivirus life cycle. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, M.; Sharma, N.; Singh, S.K. Flavivirus NS1: A multifaceted enigmatic viral protein. Virol. J. 2016, 13, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melian, E.B.; Edmonds, J.H.; Nagasaki, T.K.; Hinzman, E.; Floden, N.; Khromykh, A.A. West Nile virus NS2A protein facilitates virus-induced apoptosis independently of interferon response. J. Gen. Virol. 2013, 94, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quek, J.-P.; Ser, Z.; Chew, B.L.A.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Sobota, R.M.; Luo, D.; Phoo, W.W. Dynamic interactions of post cleaved NS2B cofactor and NS3 protease identified by integrative structural approaches. Viruses 2022, 14, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahour, A.; Falgout, B.; Lai, C.-J. Cleavage of the dengue virus polyprotein at the NS3/NS4A and NS4B/NS5 junctions is mediated by viral protease NS2B-NS3, whereas NS4A/NS4B may be processed by a cellular protease. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Thompson, E.A.; Vig, P.J.; Leis, A.A. Current understanding of West Nile virus clinical manifestations, immune responses, neuroinvasion, and immunotherapeutic implications. Pathogens 2019, 8, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Ray, D.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, H.; Ren, S.; Li, Z.; Guo, Y.; Bernard, K.A.; Shi, P.-Y.; Li, H. Structure and function of flavivirus NS5 methyltransferase. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 3891–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, K.J.; Westaway, E.G.; Khromykh, A.A. Expression and purification of enzymatically active recombinant RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (NS5) of the flavivirus Kunjin. J. Virol. Methods 2001, 92, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

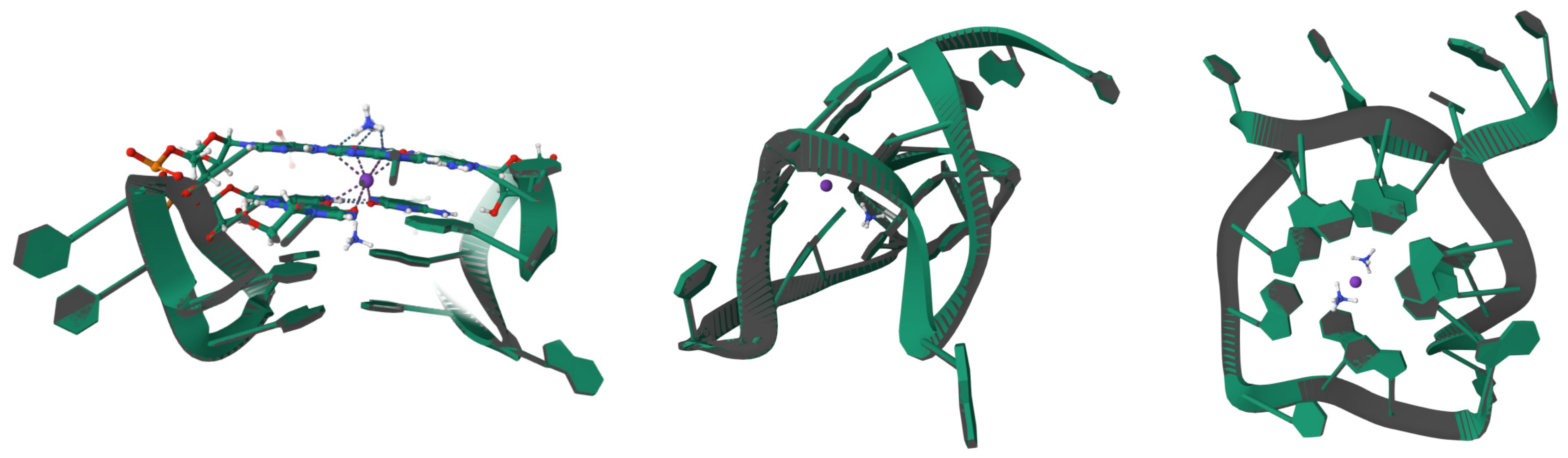

- Falanga, A.P.; Piccialli, I.; Greco, F.; D’Errico, S.; Nolli, M.G.; Borbone, N.; Oliviero, G.; Roviello, G.N. Nanostructural Modulation of G-Quadruplex DNA in Neurodegeneration: Orotate Interaction Revealed Through Experimental and Computational Approaches. J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e16296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falanga, A.P.; Terracciano, M.; Oliviero, G.; Roviello, G.N.; Borbone, N. Exploring the Relationship between G-Quadruplex Nucleic Acids and Plants: From Plant G-Quadruplex Function to Phytochemical G4 Ligands with Pharmaceutic Potential. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrell, J.R.; Le, T.T.; Paul, A.; Brinton, M.A.; Wilson, W.D.; Poon, G.M.K.; Germann, M.W.; Siemer, J.L. Structure of an RNA G-quadruplex from the West Nile virus genome. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, J.J.-H.; Ng, M.-L. Interaction of West Nile virus with αvβ3 integrin mediates virus entry into cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 54533–54541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.W.; Nguyen, H.-Y.; Hanna, S.L.; Sánchez, M.D.; Doms, R.W.; Pierson, T.C. West Nile virus discriminates between DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR for cellular attachment and infection. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 1290–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, J.; Ng, M. Infectious entry of West Nile virus occurs through a clathrin-mediated endocytic pathway. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 10543–10555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, A.; Vitale, E.; Maniaci, A.; La Via, L.; Moscatt, V.; Spampinato, S.; Senia, P.; Venanzi Rullo, E.; Restivo, V.; Cacopardo, B.; et al. West Nile Virus: Insights into Microbiology, Epidemiology, and Clinical Burden. Acta Microbiol. Hell. 2025, 70, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.-F.; Nisole, S. West Nile Virus Restriction in Mosquito and Human Cells: A Virus under Confinement. Vaccines 2020, 8, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, L.H.; Klein, D.E.; Schmidt, A.G.; Peña, J.M.; Harrison, S.C. Sequential conformational rearrangements in flavivirus membrane fusion. eLife 2014, 3, e04389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, S.; Nitsche, C. Targeting the protease of West Nile virus. RSC Med. Chem. 2021, 12, 1262–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinton, M.A. Replication cycle and molecular biology of the West Nile virus. Viruses 2014, 6, 13–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufusi, P.H.; Kelley, J.F.; Yanagihara, R.; Nerurkar, V.R. Induction of endoplasmic reticulum-derived replication-competent membrane structures by West Nile virus non-structural protein 4B. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holoubek, J.; Salát, J.; Matkovic, M.; Bednář, P.; Novotný, P.; Hradilek, M.; Majerová, T.; Rosendal, E.; Eyer, L.; Fořtová, A. Irreversible furin cleavage site exposure renders immature tick-borne flaviviruses fully infectious. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaney, M.-C.; Dellarole, M.; Duquerroy, S.; Medits, I.; Tsouchnikas, G.; Rouvinski, A.; England, P.; Stiasny, K.; Heinz, F.X.; Rey, F.A. Evolution and activation mechanism of the flavivirus class II membrane-fusion machinery. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Acebes, M.A.; Saiz, J.-C. West Nile virus: A re-emerging pathogen revisited. World J. Virol. 2012, 1, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthar, M.S.; Diamond, M.S.; Gale, M., Jr. West Nile virus infection and immunity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, G.L.; Kitron, U.D.; Brawn, J.D.; Loss, S.R.; Ruiz, M.O.; Goldberg, T.L.; Walker, E.D. Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae): A bridge vector of West Nile virus to humans. J. Med. Entomol. 2008, 45, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesen, C.; Herrador, Z.; Fernandez-Martinez, B.; Figuerola, J.; Gangoso, L.; Vazquez, A.; Gómez-Barroso, D. A systematic review of environmental factors related to WNV circulation in European and Mediterranean countries. One Health 2023, 16, 100478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jibowu, M.; Nolan, M.S.; Ramphul, R.; Essigmann, H.T.; Oluyomi, A.O.; Brown, E.L.; Vigilant, M.; Gunter, S.M. Spatial dynamics of Culex quinquefasciatus abundance: Geostatistical insights from Harris County, Texas. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2024, 23, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haba, Y.; McBride, L. Origin and status of Culex pipiens mosquito ecotypes. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, R237–R246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, S.S.; Reed, M.; Ramos, S.; Goodman, G.; Elkashef, S. Programmatic review of the mosquito control methods used in the highly industrialized rice agroecosystems of Sacramento and Yolo Counties, California. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 30, 945–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrigós, M.; Garrido, M.; Ruiz-López, M.J.; García-López, M.J.; Veiga, J.; Magallanes, S.; Soriguer, R.; Moreno-Indias, I.; Figuerola, J.; Martinez-De la Puente, J. Microbiota composition of Culex perexiguus mosquitoes during the West Nile virus outbreak in southern Spain. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0314001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, A.; Delang, L. Culex modestus: The overlooked mosquito vector. Parasites Vectors 2023, 16, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, G.; Montarsi, F.; Calzolari, M.; Capelli, G.; Dottori, M.; Ravagnan, S.; Lelli, D.; Chiari, M.; Santilli, A.; Quaglia, M. Mosquito species involved in the circulation of West Nile and Usutu viruses in Italy. Vet. Ital. 2017, 53, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Shahhosseini, N.; Chinikar, S.; Moosa-Kazemi, S.H.; Sedaghat, M.M.; Kayedi, M.H.; Lühken, R.; Schmidt-Chanasit, J. West Nile Virus lineage-2 in culex specimens from Iran. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2017, 22, 1343–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzoli, A.; Bolzoni, L.; Chadwick, E.A.; Capelli, G.; Montarsi, F.; Grisenti, M.; de la Puente, J.M.; Muñoz, J.; Figuerola, J.; Soriguer, R. Understanding West Nile virus ecology in Europe: Culex pipiens host feeding preference in a hotspot of virus emergence. Parasites Vectors 2015, 8, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciota, A.T.; Kramer, L.D. Vector-virus interactions and transmission dynamics of West Nile virus. Viruses 2013, 5, 3021–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancey, C.; Grinev, A.; Volkova, E.; Rios, M. The global ecology and epidemiology of West Nile virus. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 376230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bampali, M.; Konstantinidis, K.; Kellis, E.E.; Pouni, T.; Mitroulis, I.; Kottaridi, C.; Mathioudakis, A.G.; Beloukas, A.; Karakasiliotis, I. West Nile disease symptoms and comorbidities: A systematic review and analysis of cases. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J., Jr.; Tillman, G.; Kraut, M.A.; Chiang, H.-S.; Strain, J.F.; Li, Y.; Agrawal, A.G.; Jester, P.; Gnann, J.W., Jr.; Whitley, R.J. West Nile virus neuroinvasive disease: Neurological manifestations and prospective longitudinal outcomes. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padda, H. West Nile Virus and Other Nationally Notifiable Arboviral Diseases—United States, 2023. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2025, 74, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, L.R.; Roehrig, J.T.; Hughes, J.M. West Nile virus encephalitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1225–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.; Rincon, L.; Yassin, A.; Campbell, G.; Peng, B.; Fulton, C.; Sarria, J.; Walker, D.; Fang, X. Encephalomyelitis resulting from chronic West Nile virus infection: A case report. J. Neurol. Exp. Neurosci. 2019, 5, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Kim, C.Y.; Dean, A.; Kulas, K.E.; St George, K.; Hoang, H.E.; Thakur, K.T. Clinical and diagnostic features of West Nile virus neuroinvasive disease in New York City. Pathogens 2024, 13, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, E. Surveillance for West Nile virus disease—United States, 2009–2018. MMWR. Surveill. Summ. 2021, 70, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, J.; Hanna, S.E.; Nicolle, L.E.; Drebot, M.A.; Neupane, B.; Mahony, J.B.; Loeb, M.B. Prognosis of West Nile virus associated acute flaccid paralysis: A case series. J. Med. Case Rep. 2011, 5, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazal, F.; Simeone, S.; Nadler, E. West Nile Virus as the Rare Culprit of Acute Flaccid Paralysis and Respiratory Failure. In C105. INFECTIONS IN THE ICU: THE BEST OF THE BEST CASES; American Thoracic Society: New York, NY, USA, 2023; p. A6078. [Google Scholar]

- Maramattom, B.V.; Philips, G.; Sudheesh, N.; Arunkumar, G. Acute flaccid paralysis due to West Nile virus infection in adults: A paradigm shift entity. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2014, 17, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sejvar, J.J.; Leis, A.A.; Stokic, D.S.; Van Gerpen, J.A.; Marfin, A.A.; Webb, R.; Haddad, M.B.; Tierney, B.C.; Slavinski, S.A.; Polk, J.L. Acute flaccid paralysis and West Nile virus infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2003, 9, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Zaim, M.; Edalat, H.; Basseri, H.R.; Yaghoobi-Ershadi, M.R.; Rezaei, F.; Azizi, K.; Salehi-Vaziri, M.; Ghane, M.; Yousefi, S. Seroprevalence study on West Nile virus (WNV) infection, a hidden viral disease in Fars Province, southern Iran. J. Arthropod-Borne Dis. 2020, 14, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanità, I.S.d. Bollettino Sorveglianza Integrata West Nile e Usutu—N. 14, 15 ottobre 2025; Istituto Superiore di Sanità: Rome, Italy, 2025; Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/westNile/bollettino/Bollettino_WND_2025_14.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Sanità, I.S.d. Sorveglianza Integrata del West Nile e Usutu Virus, Bollettino N. 13 del 9 Novembre 2017. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/westNile/bollettino/Bollettino%20WND_08.11.2017.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- D’Amore, C.; Grimaldi, P.; Ascione, T.; Conti, V.; Sellitto, C.; Franci, G.; Kafil, S.H.; Pagliano, P. West Nile Virus diffusion in temperate regions and climate change. A systematic review. Infez. Med. 2023, 31, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, C.; Salcuni, P.; Nicoletti, L.; Ciufolini, M.; Russo, F.; Masala, R.; Frongia, O.; Finarelli, A.; Gramegna, M.; Gallo, L. Epidemiological surveillance of West Nile neuroinvasive diseases in Italy, 2008 to 2011. Eurosurveillance 2012, 17, 20172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (ECDC), European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. West Nile Virus Infection: Annual Epidemiological Report for 2018. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/west-nile-virus-infection-annual-epidemiological-report-2018 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC); European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Surveillance of West Nile virus infections in humans and animals in Europe, monthly report–data submitted up to 3 September 2025. Sci. Rep. 2025, 23, e9835. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, E.; Moemenbellah-Fard, M.D. Prevalence of chikungunya, dengue, and West Nile arboviruses in Iran based on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Epidemiol. 2025, 9, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohm, D.J.; O’Guinn, M.L.; Turell, M.J. Effect of environmental temperature on the ability of Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) to transmit West Nile virus. J. Med. Entomol. 2002, 39, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantari, M.; Salehi-Vaziri, M.; Pouriayevali, M.H.; Baniasadi, V.; Salmanzadeh, S.; Kharat, M.; Fazlalipour, M. Seroprevalence of West Nile virus in Khuzestan province, southwestern Iran, 2016–2017. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2019, 56, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autorino, G.L.; Battisti, A.; Deubel, V.; Ferrari, G.; Forletta, R.; Giovannini, A.; Lelli, R.; Murri, S.; Scicluna, M.T. West Nile virus epidemic in horses, Tuscany region, Italy. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002, 8, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, P.; Tamba, M.; Finarelli, A.; Bellini, R.; Albieri, A.; Bonilauri, P.; Cavrini, F.; Dottori, M.; Gaibani, P.; Martini, E. West Nile virus circulation in Emilia-Romagna, Italy: The integrated surveillance system 2009. Eurosurveillance 2010, 15, 19547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busani, L.; Capelli, G.; Cecchinato, M.; Lorenzetto, M.; Savini, G.; Terregino, C.; Vio, P.; Bonfanti, L.; Dalla Pozza, M.; Marangon, S. West Nile virus circulation in Veneto region in 2008–2009. Epidemiol. Infect. 2011, 139, 818–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calzolari, M.; Gaibani, P.; Bellini, R.; Defilippo, F.; Pierro, A.; Albieri, A.; Maioli, G.; Luppi, A.; Rossini, G.; Balzani, A. Mosquito, bird and human surveillance of West Nile and Usutu viruses in Emilia-Romagna Region (Italy) in 2010. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pupella, S.; Pisani, G.; Cristiano, K.; Catalano, L.; Grazzini, G. West Nile virus in the transfusion setting with a special focus on Italian preventive measures adopted in 2008–2012 and their impact on blood safety. Blood Transfus. 2013, 11, 563. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, C.; Napoli, C.; Venturi, G.; Pupella, S.; Lombardini, L.; Calistri, P.; Monaco, F.; Cagarelli, R.; Angelini, P.; Bellini, R. West Nile virus transmission: Results from the integrated surveillance system in Italy, 2008 to 2015. Eurosurveillance 2016, 21, 30340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaelli, M.; Verna, F.; Pautasso, A.; Bellavia, V.; Ballardini, M.; Mignone, W.; Masoero, L.; Dondo, A.; Orusa, R.; Picco, L. “One Health” approach in West Nile disease surveillance: The northwestern Italian experience. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 79, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candeloro, L.; Ippoliti, C.; Iapaolo, F.; Monaco, F.; Morelli, D.; Cuccu, R.; Fronte, P.; Calderara, S.; Vincenzi, S.; Porrello, A. Predicting WNV circulation in Italy using earth observation data and extreme gradient boosting model. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinikar, S.; Javadi, A.; Ataei, B.; Shakeri, H.; Moradi, M.; Mostafavi, E.; Ghiasi, S. Detection of West Nile virus genome and specific antibodies in Iranian encephalitis patients. Epidemiol. Infect. 2012, 140, 1525–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, R.; Kassiri, H.; Kasiri, N.; Dehghani, M. A review on epidemiology and ecology of West Nile fever: An emerging arboviral disease. J. Acute Dis. 2020, 9, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, G.; Carletti, F.; Bordi, L.; Cavrini, F.; Gaibani, P.; Landini, M.P.; Pierro, A.; Capobianchi, M.R.; Di Caro, A.; Sambri, V. Phylogenetic Analysis of West Nile Virus Isolates, Europe, 2008–2009. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 903–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, C.; Vescio, F.; Declich, S.; Finarelli, A.; Macini, P.; Mattivi, A.; Rossini, G.; Piovesan, C.; Barzon, L.; Palu, G. West Nile virus transmission with human cases in Italy, August-September 2009. Eurosurveillance 2009, 14, 19353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calistri, P.; Giovannini, A.; Savini, G.; Monaco, F.; Bonfanti, L.; Ceolin, C.; Terregino, C.; Tamba, M.; Cordioli, P.; Lelli, R. West Nile virus transmission in 2008 in north-eastern Italy. Zoonoses Public Health 2010, 57, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzolari, M.; Bonilauri, P.; Bellini, R.; Albieri, A.; Defilippo, F.; Maioli, G.; Galletti, G.; Gelati, A.; Barbieri, I.; Tamba, M. Evidence of simultaneous circulation of West Nile and Usutu viruses in mosquitoes sampled in Emilia-Romagna region (Italy) in 2009. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobbi, F.; Barzon, L.; Capelli, G.; Angheben, A.; Pacenti, M.; Napoletano, G.; Piovesan, C.; Montarsi, F.; Martini, S.; Rigoli, R. Surveillance for West Nile, dengue, and chikungunya virus infections, Veneto Region, Italy, 2010. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magurano, F.; Remoli, M.; Baggieri, M.; Fortuna, C.; Marchi, A.; Fiorentini, C.; Bucci, P.; Benedetti, E.; Ciufolini, M.; Rizzo, C. Circulation of West Nile virus lineage 1 and 2 during an outbreak in Italy. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, E545–E547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, C.; Bella, A.; Declich, S.; Grazzini, G.; Lombardini, L.; Nanni Costa, A.; Nicoletti, L.; Pompa, M.G.; Pupella, S.; Russo, F. Integrated human surveillance systems of West Nile virus infections in Italy: The 2012 experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 7180–7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, G.; Calzolari, M.; Angelini, P.; Bellini, R.; Bellini, S.; Bolzoni, L.; Torri, D.; Defilippo, F.; Dorigatti, I.; Nikolay, B. A quantitative comparison of West Nile virus incidence from 2013 to 2018 in Emilia-Romagna, Italy. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0007953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veo, C.; Della Ventura, C.; Moreno, A.; Rovida, F.; Percivalle, E.; Canziani, S.; Torri, D.; Calzolari, M.; Baldanti, F.; Galli, M. Evolutionary dynamics of the lineage 2 West Nile virus that caused the largest European epidemic: Italy 2011–2018. Viruses 2019, 11, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaziante, M.; Leone, S.; D’amato, M.; De Carli, G.; Tonziello, G.; Malatesta, G.N.; Agresta, A.; De Santis, C.; Vantaggio, V.; Pitti, G. Interrupted time series analysis to evaluate the impact of COVID-19-pandemic on the incidence of notifiable infectious diseases in the Lazio region, Italy. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzon, L.; Pacenti, M.; Montarsi, F.; Fornasiero, D.; Gobbo, F.; Quaranta, E.; Monne, I.; Fusaro, A.; Volpe, A.; Sinigaglia, A. Rapid spread of a new West Nile virus lineage 1 associated with increased risk of neuroinvasive disease during a large outbreak in Italy in 2022. J. Travel Med. 2024, 31, taac125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccardo, F.; Bella, A.; Monaco, F.; Ferraro, F.; Petrone, D.; Mateo-Urdiales, A.; Andrianou, X.D.; Del Manso, M.; Venturi, G.; Fortuna, C. Rapid increase in neuroinvasive West Nile virus infections in humans, Italy, July 2022. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27, 2200653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M. West Nile virus in Italy: The reports of its disappearance were greatly exaggerated. Pathog. Glob. Health 2022, 116, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Sorveglianza Integrata del West Nile e Usutu Virus, Bollettino N. 14 del 22 Ottobre 2020. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/westNile/bollettino/Bollettino_WND_2020_14.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Sorveglianza Integrata del West Nile e Usutu Virus, Bollettino N. 17 dell’ 11 Novembre 2021. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/westNile/bollettino/Bollettino_WND_2021_17.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Naficy, K.; Saidi, S. Serological survey on viral antibodies in Iran. Trop. Geogr. Med. 1970, 22, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Saidi, S.; Tesh, R.; Javadian, E.; Nadim, A. The prevalence of human infection with West Nile virus in Iran. Iran. J. Public Health 1976, 5, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ziyaeyan, M.; Behzadi, M.A.; Leyva-Grado, V.H.; Azizi, K.; Pouladfar, G.; Dorzaban, H.; Ziyaeyan, A.; Salek, S.; Jaber Hashemi, A.; Jamalidoust, M. Widespread circulation of West Nile virus, but not Zika virus in southern Iran. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0007022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, Z.; Mahmoudian, S.M.; Talebian, A. A study of West Nile virus infection in Iranian blood donors. Arch. Iran. Med. 2010, 13, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadnejad, F.; Otarod, V.; Fallah, M.; Lowenski, S.; Sedighi-Moghaddam, R.; Zavareh, A.; Durand, B.; Lecollinet, S.; Sabatier, P. Spread of West Nile virus in Iran: A cross-sectional serosurvey in equines, 2008–2009. Epidemiol. Infect. 2011, 139, 1587–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmahdi Borujeni, M.; Ghadrdan Mashadi, A.; Seifi Abad Shapouri, M.; Zeinvand, M. A serological survey on antibodies against West Nile virus in horses of Khuzestan province. Iran. J. Vet. Med. 2013, 7, 185–191. [Google Scholar]

- Rathore, A.P.; St John, A.L. Cross-reactive immunity among flaviviruses. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, H.E.; Pinzon Burgos, E.F.; Camacho Ortega, S.; Heredia, A.; Chua, J.V. From Antibodies to Immunity: Assessing Correlates of Flavivirus Protection and Cross-Reactivity. Vaccines 2025, 13, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardina, S.V.; Bunduc, P.; Tripathi, S.; Duehr, J.; Frere, J.J.; Brown, J.A.; Nachbagauer, R.; Foster, G.A.; Krysztof, D.; Tortorella, D. Enhancement of Zika virus pathogenesis by preexisting antiflavivirus immunity. Science 2017, 356, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejnirattisai, W.; Supasa, P.; Wongwiwat, W.; Rouvinski, A.; Barba-Spaeth, G.; Duangchinda, T.; Sakuntabhai, A.; Cao-Lormeau, V.-M.; Malasit, P.; Rey, F.A. Dengue virus sero-cross-reactivity drives antibody-dependent enhancement of infection with zika virus. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 1102–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhuami, A.O.; Lawal, N.U.; Bello, M.B.; Imam, M.U. Flavivirus cross-reactivity: Insights into e-protein conservancy, pre-existing immunity, and co-infection. Microbe 2024, 4, 100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewski, S.; Pierson, T.C. Cross-reactive flavivirus antibody: Friend and foe? Cell Host Microbe 2018, 24, 622–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrona, M.V.; Ghosh, R.; Coll, K.; Chun, C.; Yousefzadeh, M.J. The 3 I’s of immunity and aging: Immunosenescence, inflammaging, and immune resilience. Front. Aging 2024, 5, 1490302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyani, P.; Christodoulou, R.; Vassiliou, E. Immunosenescence: Aging and immune system decline. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staples, J.E.; Shankar, M.B.; Sejvar, J.J.; Meltzer, M.I.; Fischer, M. Initial and long-term costs of patients hospitalized with West Nile virus disease. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014, 90, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henríquez, R.; Munoz-Barroso, I. Viral vector-and virus-like particle-based vaccines against infectious diseases: A minireview. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtaki, N.; Takahashi, H.; Kaneko, K.; Gomi, Y.; Ishikawa, T.; Higashi, Y.; Kurata, T.; Sata, T.; Kojima, A. Immunogenicity and efficacy of two types of West Nile virus-like particles different in size and maturation as a second-generation vaccine candidate. Vaccine 2010, 28, 6588–6596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohn, G.; Jennings, G.T.; Martina, B.E.; Keller, I.; Beck, M.; Pumpens, P.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Bachmann, M.F. Research A VLP-based vaccine targeting domain III of the West Nile virus E protein protects from lethal infection in mice. Virol J. 2010, 7, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cielens, I.; Jackevica, L.; Strods, A.; Kazaks, A.; Ose, V.; Bogans, J.; Pumpens, P.; Renhofa, R. Mosaic RNA phage VLPs carrying domain III of the West Nile virus E protein. Mol. Biotechnol. 2014, 56, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tariq, H.; Batool, S.; Asif, S.; Ali, M.; Abbasi, B.H. Virus-like particles: Revolutionary platforms for developing vaccines against emerging infectious diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 790121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chianese, A.; Stelitano, D.; Astorri, R.; Serretiello, E.; Della Rocca, M.T.; Melardo, C.; Vitiello, M.; Galdiero, M.; Franci, G. West Nile virus: An overview of current information. Transl. Med. Rep. 2019, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, K.Y.; Tham, S.K.; Poh, C.L. Revolutionizing immunization: A comprehensive review of mRNA vaccine technology and applications. Virol. J. 2025, 22, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, N.; Su, Z.; Zheng, X. Research progress of mosquito-borne virus mRNA vaccines. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2025, 33, 101398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollner, C.J.; Richner, J.M. mRNA vaccines against flaviviruses. Vaccines 2021, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello, M.B.; Alsaadi, A.; Naeem, A.; Almahboub, S.A.; Bosaeed, M.; Aljedani, S.S. Development of nucleic acid-based vaccines against dengue and other mosquito-borne flaviviruses: The past, present, and future. Front. Immunol. 2025, 15, 1475886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isakova-Sivak, I.; Rudenko, L. Next-generation influenza vaccines based on mRNA technology. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneeweiss, A.; Chabierski, S.; Salomo, M.; Delaroque, N.; Al-Robaiy, S.; Grunwald, T.; Bürki, K.; Liebert, U.G.; Ulbert, S. A DNA vaccine encoding the E protein of West Nile virus is protective and can be boosted by recombinant domain DIII. Vaccine 2011, 29, 6352–6357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, K.; Bakonyi, T.; Szenci, O.; Sardi, S.; Ferenczi, E.; Barna, M.; Malik, P.; Hubalek, Z.; Fehér, O.; Kutasi, O. Comparison of assays for the detection of West Nile virus antibodies in equine serum after natural infection or vaccination. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2017, 183, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledgerwood, J.E.; Pierson, T.C.; Hubka, S.A.; Desai, N.; Rucker, S.; Gordon, I.J.; Enama, M.E.; Nelson, S.; Nason, M.; Gu, W. A West Nile virus DNA vaccine utilizing a modified promoter induces neutralizing antibody in younger and older healthy adults in a phase I clinical trial. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 203, 1396–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepp-Berglind, J.; Luo, M.; Wang, D.; Wicker, J.A.; Raja, N.U.; Hoel, B.D.; Holman, D.H.; Barrett, A.D.; Dong, J.Y. Complex adenovirus-mediated expression of West Nile virus C, PreM, E, and NS1 proteins induces both humoral and cellular immune responses. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2007, 14, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobernik, D.; Bros, M. DNA vaccines—How far from clinical use? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.A. A Comparison of Plasmid DNA and mRNA as Vaccine Technologies. Vaccines 2019, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eusébio, D.; Neves, A.R.; Costa, D.; Biswas, S.; Alves, G.; Cui, Z.; Sousa, Â. Methods to improve the immunogenicity of plasmid DNA vaccines. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 2575–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraki, Y.; Fujita, T.; Matsuura, M.; Fuke, I.; Manabe, S.; Ishikawa, T.; Okuno, Y.; Morita, K. The efficacy of inactivated West Nile vaccine (WN-VAX) in mice and monkeys. Virol. J. 2015, 12, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.-K.; Takasaki, T.; Kotaki, A.; Kurane, I. Vero cell-derived inactivated West Nile (WN) vaccine induces protective immunity against lethal WN virus infection in mice and shows a facilitated neutralizing antibody response in mice previously immunized with Japanese encephalitis vaccine. Virology 2008, 374, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posadas-Herrera, G.; Inoue, S.; Fuke, I.; Muraki, Y.; Mapua, C.A.; Khan, A.H.; del Carmen Parquet, M.; Manabe, S.; Tanishita, O.; Ishikawa, T. Development and evaluation of a formalin-inactivated West Nile Virus vaccine (WN-VAX) for a human vaccine candidate. Vaccine 2010, 28, 7939–7946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamshchikov, G.; Borisevich, V.; Seregin, A.; Chaporgina, E.; Mishina, M.; Mishin, V.; Kwok, C.W.; Yamshchikov, V. An attenuated West Nile prototype virus is highly immunogenic and protects against the deadly NY99 strain: A candidate for live WN vaccine development. Virology 2004, 330, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedenbender, R.; Bevilacqua, J.; Gregg, A.M.; Watson, M.; Dayan, G. Phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study to investigate the immunogenicity and safety of a West Nile virus vaccine in healthy adults. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 203, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, J.; Miller, C.; Catalan, J.; Myers, G.A.; Ratterree, M.S.; Trent, D.W.; Monath, T.P. ChimeriVax-West Nile virus live-attenuated vaccine: Preclinical evaluation of safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 12497–12507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, G.H.; Pugachev, K.; Bevilacqua, J.; Lang, J.; Monath, T.P. Preclinical and clinical development of a YFV 17 D-based chimeric vaccine against West Nile virus. Viruses 2013, 5, 3048–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, J.A.; Barrett, A.D. Twenty years of progress toward West Nile virus vaccine development. Viruses 2019, 11, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Gibbs, E.; Mellencamp, M.; Bowen, R.; Seino, K.; Zhang, S.; Beachboard, S.; Humphrey, P. Efficacy, duration, and onset of immunogenicity of a West Nile virus vaccine, live Flavivirus chimera, in horses with a clinical disease challenge model. Equine Vet. J. 2007, 39, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlova, O.V.; Glazkova, D.V.; Bogoslovskaya, E.V.; Shipulin, G.A.; Yudin, S.M. Development of modified vaccinia virus Ankara-based vaccines: Advantages and applications. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, A.; Lim, S.; Kaserer, M.; Lülf, A.; Marr, L.; Jany, S.; Deeg, C.A.; Pijlman, G.P.; Koraka, P.; Osterhaus, A.D. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of recombinant Modified Vaccinia virus Ankara candidate vaccines delivering West Nile virus envelope antigens. Vaccine 2016, 34, 1915–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlers, L.R.; Goodman, A.G. The immune responses of the animal hosts of West Nile virus: A comparison of insects, birds, and mammals. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (AAEP), American Association of Equine Practitioners. West Nile Virus Vaccination Guidelines. Available online: https://aaep.org/resource/west-nile-virus-vaccination-guidelines/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Naveed, A.; Eertink, L.G.; Wang, D.; Li, F. Lessons Learned from West Nile Virus Infection:Vaccinations in Equines and Their Implications for One Health Approaches. Viruses 2024, 16, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agency, E.M. Annex I–III: Proteq West Nile—Summary of Product Characteristics, Labelling and Package Leaflet; European Medicines Agency: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- El Garch, H.; Minke, J.; Rehder, J.; Richard, S.; Toulemonde, C.E.; Dinic, S.; Andreoni, C.; Audonnet, J.; Nordgren, R.; Juillard, V. A West Nile virus (WNV) recombinant canarypox virus vaccine elicits WNV-specific neutralizing antibodies and cell-mediated immune responses in the horse. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2008, 123, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletnev, A.G.; Swayne, D.E.; Speicher, J.; Rumyantsev, A.A.; Murphy, B.R. Chimeric West Nile/dengue virus vaccine candidate: Preclinical evaluation in mice, geese and monkeys for safety and immunogenicity. Vaccine 2006, 24, 6392–6404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletnev, A.G.; St Claire, M.; Elkins, R.; Speicher, J.; Murphy, B.R.; Chanock, R.M. Molecularly engineered live-attenuated chimeric West Nile/dengue virus vaccines protect rhesus monkeys from West Nile virus. Virology 2003, 314, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, M.M.; Nerurkar, V.R.; Luo, H.; Cropp, B.; Carrion, R., Jr.; De La Garza, M.; Coller, B.-A.; Clements, D.; Ogata, S.; Wong, T. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a recombinant subunit West Nile virus vaccine in rhesus monkeys. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2009, 16, 1332–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (EMA), European Medicines Agency. Proteq West Nile. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/veterinary/EPAR/proteq-west-nile?utm (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Bakhshi, H.; Beck, C.; Lecollinet, S.; Monier, M.; Mousson, L.; Zakeri, S.; Raz, A.; Arzamani, K.; Nourani, L.; Dinparast-Djadid, N. Serological evidence of West Nile virus infection among birds and horses in some geographical locations of Iran. Vet. Med. Sci. 2021, 7, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaca, K.; Bowen, R.; Austgen, L.; Teehee, M.; Siger, L.; Grosenbaugh, D.; Loosemore, L.; Audonnet, J.-C.; Nordgren, R.; Minke, J. Recombinant canarypox vectored West Nile virus (WNV) vaccine protects dogs and cats against a mosquito WNV challenge. Vaccine 2005, 23, 3808–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-Q.; Li, N.; Zhang, Z.-R.; Deng, C.-L.; Xia, H.; Ye, H.-Q.; Yuan, Z.-M.; Zhang, B. A chimeric classical insect-specific flavivirus provides complete protection against West Nile virus lethal challenge in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 229, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutzler, M.A.; Baker, R.J.; Mattson, D.E. Humoral response to West Nile virus vaccination in alpacas and llamas. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2004, 225, 414–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fik-Jaskółka, M.A.; Mkrtchyan, A.F.; Saghyan, A.S.; Palumbo, R.; Belter, A.; Hayriyan, L.A.; Simonyan, H.; Roviello, V.; Roviello, G.N. Spectroscopic and SEM evidences for G4-DNA binding by a synthetic alkyne-containing amino acid with anticancer activity. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 229, 117884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roviello, V.; Musumeci, D.; Mokhir, A.; Roviello, G.N. Evidence of Protein Binding by a Nucleopeptide Based on a Thyminedecorated L-Diaminopropanoic Acid through CD and In Silico Studies. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 5004–5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, M.; Falanga, A.P.; Marasco, D.; Borbone, N.; D’Errico, S.; Piccialli, G.; Roviello, G.N.; Oliviero, G. Evaluation of an Analogue of the Marine ε-PLL Peptide as a Ligand of G-quadruplex DNA Structures. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, G.N.; Ricci, A.; Bucci, E.M.; Pedone, C. Synthesis, biological evaluation and supramolecular assembly of novel analogues of peptidyl nucleosides. Mol. Biosyst. 2011, 7, 1773–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, G.N.; Musumeci, D.; Pedone, C.; Bucci, E.M. Synthesis, characterization and hybridization studies of an alternate nucleo-ε/γ-peptide: Complexes formation with natural nucleic acids. Amino Acids 2008, 38, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musumeci, D.; Oliviero, G.; Roviello, G.N.; Bucci, E.M.; Piccialli, G. G-Quadruplex-Forming Oligonucleotide Conjugated to Magnetic Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Enzymatic Stability Assays. Bioconjug. Chem. 2012, 23, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, G.N.; Gaetano, S.D.; Capasso, D.; Cesarani, A.; Bucci, E.M.; Pedone, C. Synthesis, spectroscopic studies and biological activity of a novel nucleopeptide with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase inhibitory activity. Amino Acids 2009, 38, 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, G.N.; Roviello, V.; Autiero, I.; Saviano, M. Solid phase synthesis of TyrT, a thymine–tyrosine conjugate with poly(A) RNA-binding ability. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 27607–27613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scognamiglio, P.L.; Tesauro, D.; Roviello, G.N. Metallogels as Supramolecular Platforms for Biomedical Applications: A Review. Processes 2025, 13, 3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargsyan, T.; Simonyan, H.M.; Stepanyan, L.; Tsaturyan, A.; Vicidomini, C.; Pastore, R.; Guerra, G.; Roviello, G.N. Neuroprotective Properties of Clove (Syzygium aromaticum): State of the Art and Future Pharmaceutical Applications for Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargsyan, T.; Stepanyan, L.; Tsaturyan, A.; Palumbo, R.; Vicidomini, C.; Roviello, G.N. Intracellular Parasitic Infections Caused by Plasmodium falciparum, Leishmania spp., Toxoplasma gondii, Echinococcus multilocularis, Among Key Pathogens: Global Burden, Transmission Dynamics, and Vaccine Advances—A Narrative Review with Contextual Insights from Armenia. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, M.; Roviello, G.N. Precision Therapeutics Through Bioactive Compounds: Metabolic Reprogramming, Omics Integration, and Drug Repurposing Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicidomini, C.; Roviello, G.N. Therapeutic Convergence in Neurodegeneration: Natural Products, Drug Repurposing, and Biomolecular Targets. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargsyan, T.; Stepanyan, L.; Panosyan, H.; Hakobyan, H.; Israyelyan, M.; Tsaturyan, A.; Hovhannisyan, N.; Vicidomini, C.; Mkrtchyan, A.; Saghyan, A. Synthesis and antifungal activity of Fmoc-protected 1, 2, 4-triazolyl-α-amino acids and their dipeptides against Aspergillus species. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, B.T.; Thompson, E.P.; Roviello, G.N.; Gale, T.F. C-Terminal Analogues of Camostat Retain TMPRSS2 Protease Inhibition: New Synthetic Directions for Antiviral Repurposing of Guanidinium-Based Drugs in Respiratory Infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargsyan, T.; Hakobyan, H.; Simonyan, H.; Soghomonyan, T.; Tsaturyan, A.; Hovhannisyan, A.; Sardaryan, S.; Saghyan, A.; Roviello, G.N. Biomacromolecular interactions and antioxidant properties of novel synthetic amino acids targeting DNA and serum albumin. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 440, 128700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanyan, L.; Sargsyan, T.; Mittova, V.; Tsetskhladze, Z.R.; Motsonelidze, N.; Gorgoshidze, E.; Nova, N.; Israyelyan, M.; Simonyan, H.; Bisceglie, F. The Synthesis, Characterization, and Biological Evaluation of a Fluorenyl-Methoxycarbonyl-Containing Thioxo-Triazole-Bearing Dipeptide: Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and BSA/DNA Binding Studies for Potential Therapeutic Applications in ROS Scavenging and Drug Transport. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 933. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, H.; Palumbo, R.; Vicidomini, C.; Scognamiglio, P.L.; Petrosyan, S.; Sahakyan, L.; Melikyan, G.; Saghyan, A.; Roviello, G.N. Binding of G-quadruplex DNA and serum albumins by synthetic non-proteinogenic amino acids: Implications for c-Myc-related anticancer activity and drug delivery. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2025, 36, 102478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayriyan, L.; Grigoryan, A.; Gevorgyan, H.; Tsaturyan, A.; Sargsyan, A.; Langer, P.; Saghyan, A.; Mkrtchyan, A. A3-Mannich coupling reaction via chiral propargylglycine Ni(ii) complex: An approach for synthesizing enantiomerically enriched unnatural α-amino acids. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 35379–35387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovmasyan, A.S.; Mkrtchyan, A.F.; Tsaturyan, A.H.; Langer, P.; Malkov, A.V.; Saghyan, A.S. Strategy for synthesizing O-protected (S)-α-substituted serine analogs via sequential Ni(ii)-complex-mediated cross-coupling and cycloaddition reactions. New J. Chem. 2025, 49, 11640–11645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadayan, A.S.; Mkrtchyan, A.F.; Poghosyan, A.S.; Dadayan, S.A.; Stepanyan, L.A.; Israyelyan, M.H.; Tovmasyan, A.S.; Tsaturyan, A.H.; Hovhannisyan, N.A.; Topuzyan, V.O.; et al. Unnatural Phosphorus-Containing α-Amino Acids and Their N-FMOC Derivatives: Synthesis and In Vitro Investigation of Anticholinesterase Activity. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202303249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovmasyan, A.S.; Mkrtchyan, A.F.; Khachatryan, H.N.; Hayrapetyan, M.V.; Hakobyan, R.M.; Poghosyan, A.S.; Tsaturyan, A.H.; Minasyan, E.V.; Maleev, V.I.; Larionov, V.A.; et al. Synthesis, Characterization, and Study of Catalytic Activity of Chiral Cu(II) and Ni(II) Salen Complexes in the α-Amino Acid C-α Alkylation Reaction. Molecules 2023, 28, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkrtchyan, A.F.; Hayriyan, L.A.; Karapetyan, A.J.; Tovmasyan, A.S.; Tsaturyan, A.H.; Khrustalev, V.N.; Maleev, V.I.; Saghyan, A.S. Using the Ni-[(benzylprolyl)amino]benzophenone complex in the Glaser reaction for the synthesis of bis α-amino acids. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 11927–11932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkrtchyan, A.F.; Saghyan, A.S.; Hayriyan, L.A.; Sargsyan, A.S.; Karapetyan, A.J.; Tovmasyan, A.S.; Tsaturyan, A.H.; Minasyan, E.V.; Poghosyan, A.S.; Paloyan, A.M.; et al. Asymmetric synthesis, biological activity and molecular docking studies of some unsaturated α-amino acids, derivatives of glycine, allylglycine and propargylglycine. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1208, 127850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parpart, S.; Petrosyan, A.; Ali Shah, S.J.; Adewale, R.A.; Ehlers, P.; Grigoryan, T.; Mkrtchyan, A.F.; Mardiyan, Z.Z.; Karapetyan, A.J.; Tsaturyan, A.H.; et al. Synthesis of optically pure (S)-2-amino-5-arylpent-4-ynoic acids by Sonogashira reactions and their potential use as highly selective potent inhibitors of aldose reductase. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 107400–107412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicidomini, C.; Fontanella, F.; D’Alessandro, T.; Roviello, G.N.; De Stefano, C.; Stocchi, F.; Quarantelli, M.; De Pandis, M.F. Resting-state functional MRI metrics to detect freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease: A machine learning approach. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 192, 110244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, G.N. Nature-Inspired Pathogen and Cancer Protein Covalent Inhibitors: From Plants and Other Natural Sources to Drug Development. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagiyan, V.; Zakoyan, A.; Verdyan, A.; Ghazanchyan, N.; Kinosyan, M.; Davidyan, T.; Harutyunyan, B.; Hovhannisyan, S.; Soghomonyan, T.; Goginyan, V.; et al. Yeast whey-enriched bread: Nutritional profile and potential functional relevance. Funct. Foods Health Dis. 2025, 15, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghajanyan, A.; Avagyan, G.; Tsaturyan, A.; Hovhannisyan, G.; Yeghiyan, K.; Gasparyan, N.; Tadevosyan, A.; Martirosyan, H. Valorization of grape pomace through melanin extraction and its biostimulant effects on yield and development of winter barley. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2025, 85, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovsepyan, A.; Petrosyan, T.; Saghatelyan, L.; Tsaturyan, A.; Paronyan, M.; Koloyan, H.; Hovhannisyan, S.; Abrahamyan, M.; Avetisyan, S. Safety evaluation of bacterial melanin as a plant growth stimulant for agricultural and food industry applications. Funct. Food Sci.—Online 2025, 5, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghajanyan, A.; Minasyan, E.; Soghomonyan, T.; Melyan, G.; Hovhannisyan, G.; Yeghiyan, K.; Karapetyan, K.; Tsaturyan, A. Isolation, purification, identification of melanin from grape pomace extracts, and its application areas. Bioact. Compd. Health Dis.—Online 2025, 8, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minasyan, E.; Aghajanyan, A.; Karapetyan, K.; Khachaturyan, N.; Hovhannisyan, G.; Yeghyan, K.; Tsaturyan, A. Antimicrobial Activity of Melanin Isolated from Wine Waste. Indian J. Microbiol. 2023, 64, 1528–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghajanyan, A.E.; Hambardzumyan, A.A.; Minasyan, E.V.; Hovhannisyan, G.J.; Yeghiyan, K.I.; Soghomonyan, T.M.; Avetisyan, S.V.; Sakanyan, V.A.; Tsaturyan, A.H. Efficient isolation and characterization of functional melanin from various plant sources. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 3545–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagiyan, V.; Chitchyan, K.; Goginyan, V.; Tsaturyan, A. Baker’s yeast of the ttkhmor with high α-glucosidase activity for cultivation on whey. Food Humanit. 2024, 2, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poladyan, A.; Trchounian, K.; Paloyan, A.; Minasyan, E.; Aghekyan, H.; Iskandaryan, M.; Khoyetsyan, L.; Aghayan, S.; Tsaturyan, A.; Antranikian, G. Valorization of whey-based side streams for microbial biomass, molecular hydrogen, and hydrogenase production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 4683–4696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanyan, L.A. Study of the Chemical Composition, Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activity of Various Extracts of the Aerial Part of Leonurus Cardiaca. Farmacia 2023, 71, 1064–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaturyan, A.; Arstamyan, L.; Sargsyan, A.; Saribekyan, J.; Voskanyan, A.; Minasyan, E.; Israelyan, M.; Sargsyan, T.; Stepanyan, L. Development of an efficient method for obtaining lactose and lactulose from whey. Pharmacia 2023, 70, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghajanyan, A.E.; Hambardzumyan, A.A.; Minasyan, E.V.; Tsaturyan, A.H.; Paloyan, A.M.; Avetisyan, S.V.; Hovsepyan, A.S.; Saghyan, A.S. Development of the technology for producing water-soluble melanin from waste of vinary production and the study of its physicochemical properties. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 248, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaturyan, A.; Sahakyan, L.; Hayrapetyan, L.; Minasyan, E.; Chakhoyan, A.; Hayrapetyan, S.; Saghyan, A. Ion-chromatographic determination of common anions in drinking water in some regions of the Republic of Armenia. Pharmacia 2024, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirakosyan, V.G.; Tsaturyan, A.H.; Poghosyan, L.E.; Minasyan, E.V.; Petrosyan, H.R.; Sahakyan, L.Y.; Sargsyan, T.H. Detection and development of a quantitation method for undeclared compounds in antidiabetic biologically active additives and its validation by high performance liquid chromatography. Pharmacia 2022, 69, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertinková, P.; Mochnáčová, E.; Bhide, K.; Kulkarni, A.; Tkáčová, Z.; Hruškovicová, J.; Bhide, M. Development of peptides targeting receptor binding site of the envelope glycoprotein to contain the West Nile virus infection. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.U.; Keya, C.A.; Das, K.C.; Hashem, A.; Omar, T.M.; Khan, M.A.; Rakib-Uz-Zaman, S.; Salimullah, M. An immunopharmacoinformatics approach in development of vaccine and drug candidates for West Nile virus. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsche, C.; Zhang, L.; Weigel, L.F.; Schilz, J.; Graf, D.; Bartenschlager, R.; Hilgenfeld, R.; Klein, C.D. Peptide–boronic acid inhibitors of flaviviral proteases: Medicinal chemistry and structural biology. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A.A.; Espinosa, B.A.; Adamek, R.N.; Thomas, B.A.; Chau, J.; Gonzalez, E.; Keppetipola, N.; Salzameda, N.T. Breathing new life into West Nile virus therapeutics; discovery and study of zafirlukast as an NS2B-NS3 protease inhibitor. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 157, 1202–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoreński, M.; Milewska, A.; Pyrć, K.; Sieńczyk, M.; Oleksyszyn, J. Phosphonate inhibitors of West Nile virus NS2B/NS3 protease. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019, 34, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, A.S.; Gazolla, P.A.; Oliveira, A.F.C.d.S.; Pereira, W.L.; de S. Viol, L.C.; Maia, A.F.d.S.; Santos, E.G.; da Silva, Í.E.; Mendes, T.A.d.O.; da Silva, A.M. Discovery of novel West Nile Virus protease inhibitor based on isobenzonafuranone and triazolic derivatives of eugenol and indan-1, 3-dione scaffolds. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinigaglia, A.; Peta, E.; Riccetti, S.; Barzon, L. New avenues for therapeutic discovery against West Nile virus. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2020, 15, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konaklieva, M.I.; Plotkin, B.J. β-Lactams and Ureas as Cross Inhibitors of Prokaryotic Systems. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 3, 605–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, M.; Yang, F.; Zhang, B.; Zou, G.; Robida, J.M.; Yuan, Z.; Tang, H.; Shi, P.-Y. Cyclosporine inhibits flavivirus replication through blocking the interaction between host cyclophilins and viral NS5 protein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 3226–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.N.; Maher, B.; Wang, C.; Wagstaff, K.M.; Fraser, J.E.; Jans, D.A. High throughput screening targeting the dengue NS3-NS5 interface identifies antivirals against dengue, zika and West Nile viruses. Cells 2022, 11, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Vaccine Platform | Specific Candidate/Strain | Key Mechanism & Features | Development Status & Key Observations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus-Like particles | WNV VLPs (Insect/Mammalian); Mosaic nanoparticles (AP205-DIII) | Structurally mimic the virus (prM & E proteins) without genetic material; display antigens in native conformation. | Preclinical (Animal Models): Induces neutralizing antibodies; supports DIVA strategy (differentiation of infected vs. vaccinated animals) due to lack of NS proteins. | [140,141,142,143] |

| mRNA vaccines | Lipid nanoparticle (LNP) formulations | Synthetic mRNA encoding WNV antigens; facilitates endogenous protein synthesis and dual immune response (Humoral & Cellular). | Preclinical: Not yet in clinical trials for WNV; extrapolated success from Zika/Dengue models; challenges regarding cold-chain distribution (−20 °C to −70 °C). | [146,147,148,149,150] |

| DNA vaccines | Plasmid encoding prM/E (e.g., CMV/R promoter-driven) | Non-pathogenic plasmids expressing WNV glycoproteins in host cells; capable of expressing additional proteins (e.g., Capsid, NS1). | Phase I clinical trial: Safe and immunogenic; 3 doses induced neutralizing antibodies in >95% of participants (including elderly); no licensed human DNA vaccine yet. | [23,151,152,153,154] |

| Inactivated (Vero-derived) | WN-VAX (Strain NY99-35262) | Whole virus inactivated and propagated in Vero cells; uses established manufacturing technology. | Preclinical: Safe and reliable; enhanced immunogenicity observed in mice with pre-existing Japanese Encephalitis immunity. | [158,159,162] |

| Live-attenuated | WN1415 (Based on Lineage II B956) | Utilization of less virulent Lineage II strains to reduce safety concerns. | Preclinical: Low doses (55 PFU) protected ~67% of mice; higher doses provided 100% protection against lethal challenge. | [161,162] |

| Chimeric vaccines | ChimeriVax-WN02; WN/DEN4Δ30 | WNV structural genes are inserted into a foreign backbone (e.g., Yellow Fever 17D or Dengue-4) with attenuating mutations. | Phase I Clinical Trial: ChimeriVax-WN02 showed 100% seroconversion in adults; reduced neurovirulence compared to parent strains. | [5,153,163,164,165,166] |

| Viral vectors | MVA-WNV (Modified Vaccinia Ankara) | Non-replicating vector expressing E-antigen; highly expressed in host cells without vector replication. | Preclinical: Complete protection against Lineage 1 & 2 strains; induces both antibody and T-cell responses; suitable for emergency vaccination. | [165,167,168] |

| licensed veterinary vaccines | Equip WNV (inactivated); Proteq WNV (recombinant); Equilis WNV (chimeric) | Various platforms (Inactivated whole virus, Canarypox vector, YF-chimera) specifically formulated for equines. | Licensed (Veterinary Use): High efficacy in horses (94–100% protection from viremia); Canarypox vector shows longer-lasting immunity (12 months); PreveNile (chimeric) was withdrawn due to adverse events. | [23,164,165,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176] |

| Molecular Target | Compound Class/Strategy | Specific Candidates/Examples | Key Mechanism & Observations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E Protein (Structural/DIII Domain) | Peptide-based inhibitor | Cyclic peptides; neutralizing derivatives | Inhibit receptor binding and viral replication; capable of crossing the blood–brain barrier in animal models. | [222] |

| E Protein (Structural/DIII Domain) | Immunotherapy | Humanized monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) | Show protective effects even during established neuroinvasion. | [5] |

| E Protein (Structural) | Small molecules | AP30451 and related compounds | Block E protein functions by interfering with RNA translation and replicon activity. | [223] |

| NS3 Protease (Non-structural) | Covalent inhibitors | Dipeptidic inhibitors with C-terminal boronic acid | Effective inhibition of viral replication. | [224] |

| NS3 Protease (Non-structural) | Repurposed & synthetic drugs | Zafirlukast; Cbz-Lys-Arg-(4-GuPhe)P(OPh)2 | Potent activity shown in molecular docking and experimental studies. | [225,226] |

| NS3 Protease (Non-structural) | Natural product derivatives | Eugenol-based triazoles | Potent activity in experimental studies. | [227] |

| NS3 Protease (Non-structural) | Competitive inhibitors (HTS) | Tolcapone; Tannic acid; Catechol derivatives | Strong protease inhibition identified via high-throughput screening. | [228] |

| NS3 Protease (Non-structural) | Peptidomimetics | Tripeptide-bound β-lactams | Demonstrate dual mechanisms of NS3 inhibition. | [229] |

| NS5 Protease (Non-structural) | Host-targeting agent | Cyclosporine | Interferes with NS5-associated cyclophilin activity (requires further in vivo validation). | [230] |

| NS3-NS5 Interaction (PPI) | Small molecule inhibitors | Tyrphostin derivatives; Suramin | Broad-spectrum antiviral activity; reduced viral loads in animal models. | [231] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Najafi, S.; Jojani, M.; Najafi, K.; Costanzo, V.; Vicidomini, C.; Roviello, G.N. West Nile Virus: Epidemiology, Surveillance, and Prophylaxis with a Comparative Insight from Italy and Iran. Vaccines 2026, 14, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010057

Najafi S, Jojani M, Najafi K, Costanzo V, Vicidomini C, Roviello GN. West Nile Virus: Epidemiology, Surveillance, and Prophylaxis with a Comparative Insight from Italy and Iran. Vaccines. 2026; 14(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010057

Chicago/Turabian StyleNajafi, Soroosh, Maryam Jojani, Kianoosh Najafi, Vincenzo Costanzo, Caterina Vicidomini, and Giovanni N. Roviello. 2026. "West Nile Virus: Epidemiology, Surveillance, and Prophylaxis with a Comparative Insight from Italy and Iran" Vaccines 14, no. 1: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010057

APA StyleNajafi, S., Jojani, M., Najafi, K., Costanzo, V., Vicidomini, C., & Roviello, G. N. (2026). West Nile Virus: Epidemiology, Surveillance, and Prophylaxis with a Comparative Insight from Italy and Iran. Vaccines, 14(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010057