Spatial Segregation Within Dissolving Microneedle Patches Overcomes Antigenic Interference and Enables Potent Bivalent Influenza–RSV Vaccination in Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Flu and RSV Vaccines Used in This Study

2.2. Fabrication of D-MAPs Laden with Flu, RSV, or Flu–RSV Vaccines

2.3. Western Blot

2.4. Animal Immunization

2.5. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

2.6. RSV Neutralization Assay

2.7. Hemagglutination Inhibition Assay

2.8. Live RSV Challenge In Vivo and RSV Load Determination by PCR

2.9. Live Flu Virus Challenge In Vivo

2.10. Statistics

3. Results

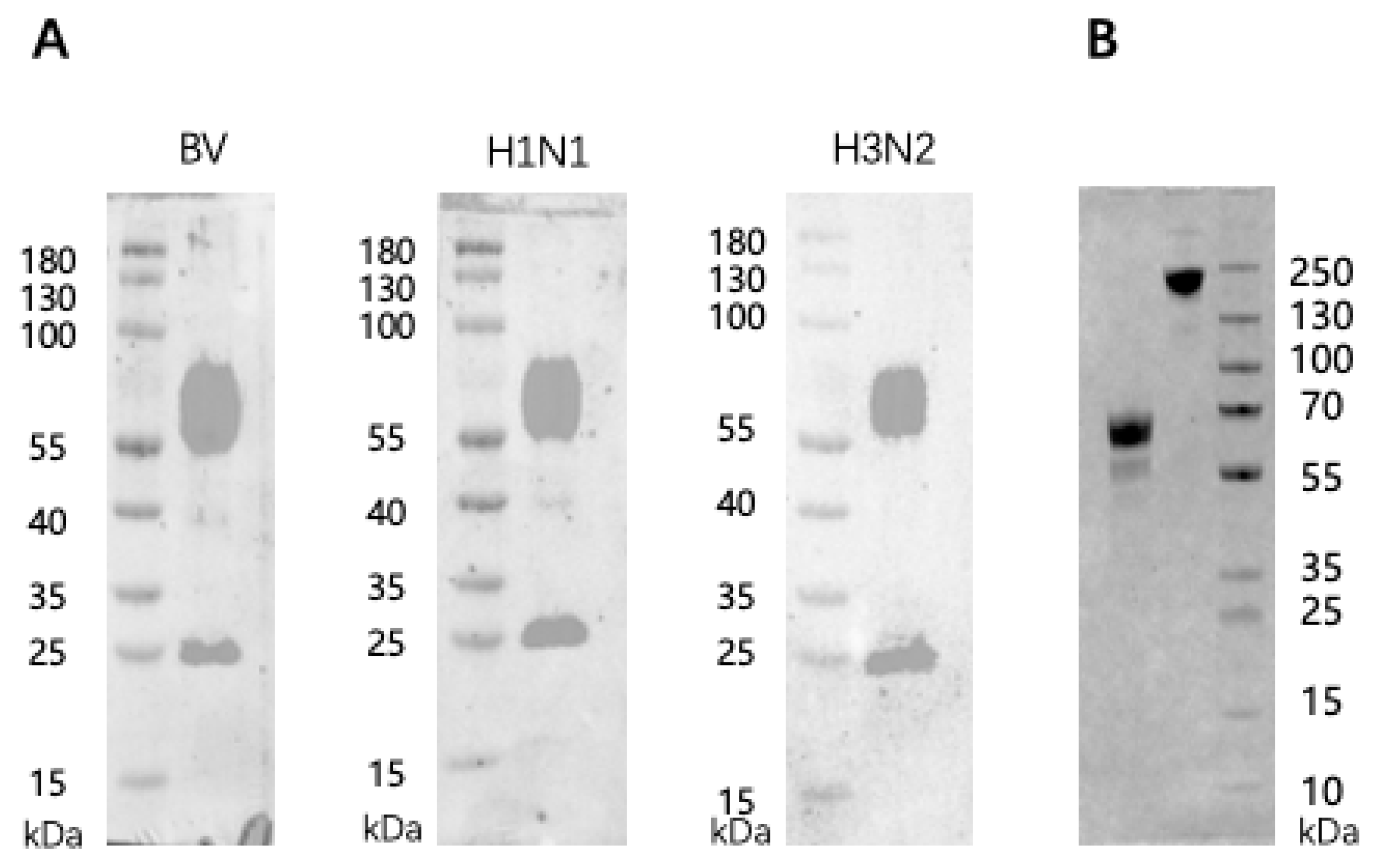

3.1. Antigenic Characteristics of the Trivalent Inactivated Flu and the Recombinant PreF RSV Vaccines

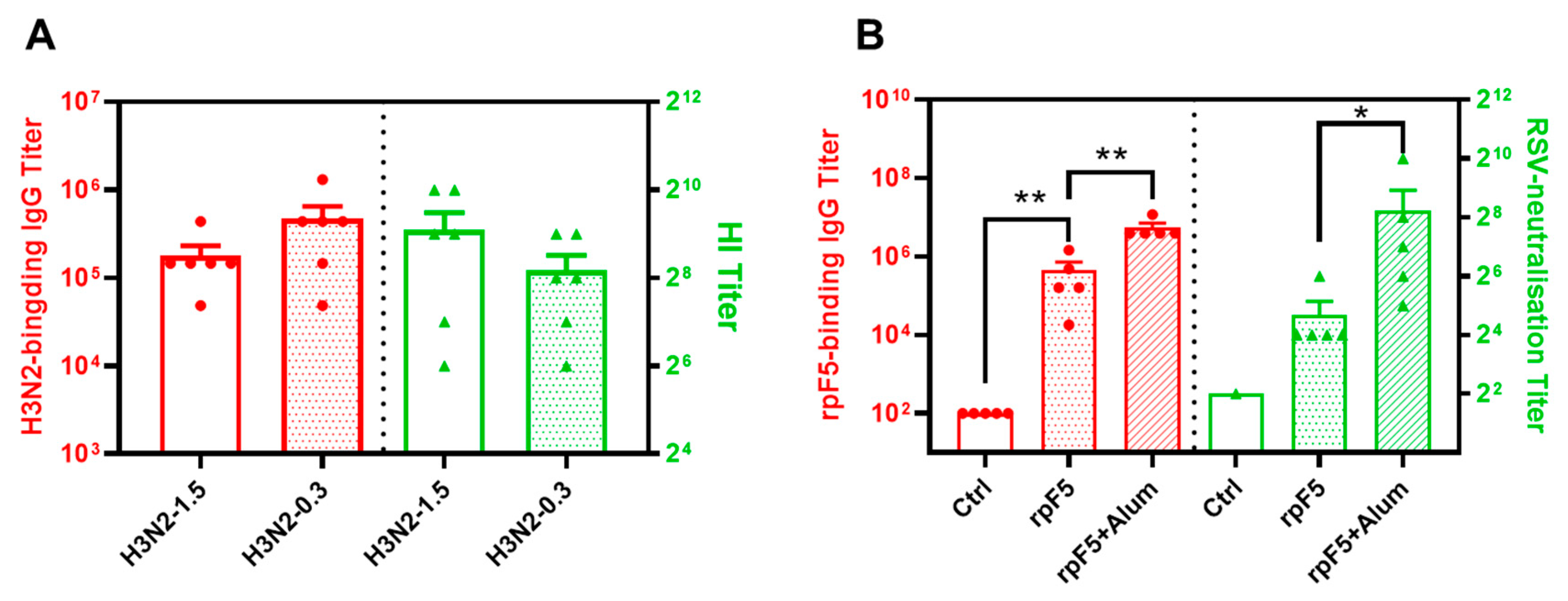

3.2. Immunogenicity of the Flu and rpF5 Vaccine Preparations in Mice

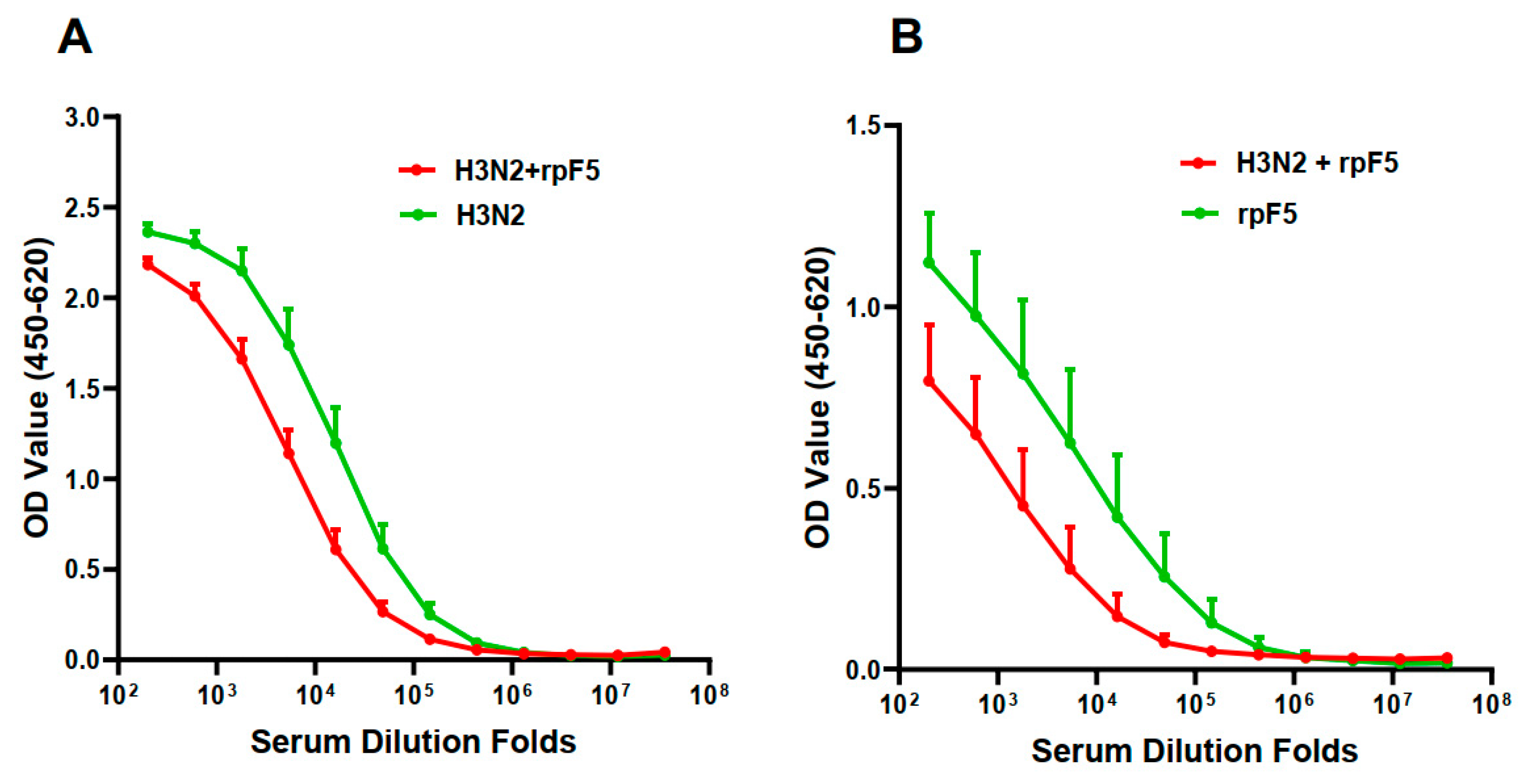

3.3. Intra-Vaccine Interference of the Premixed Flu–RSV Combo-Vaccine

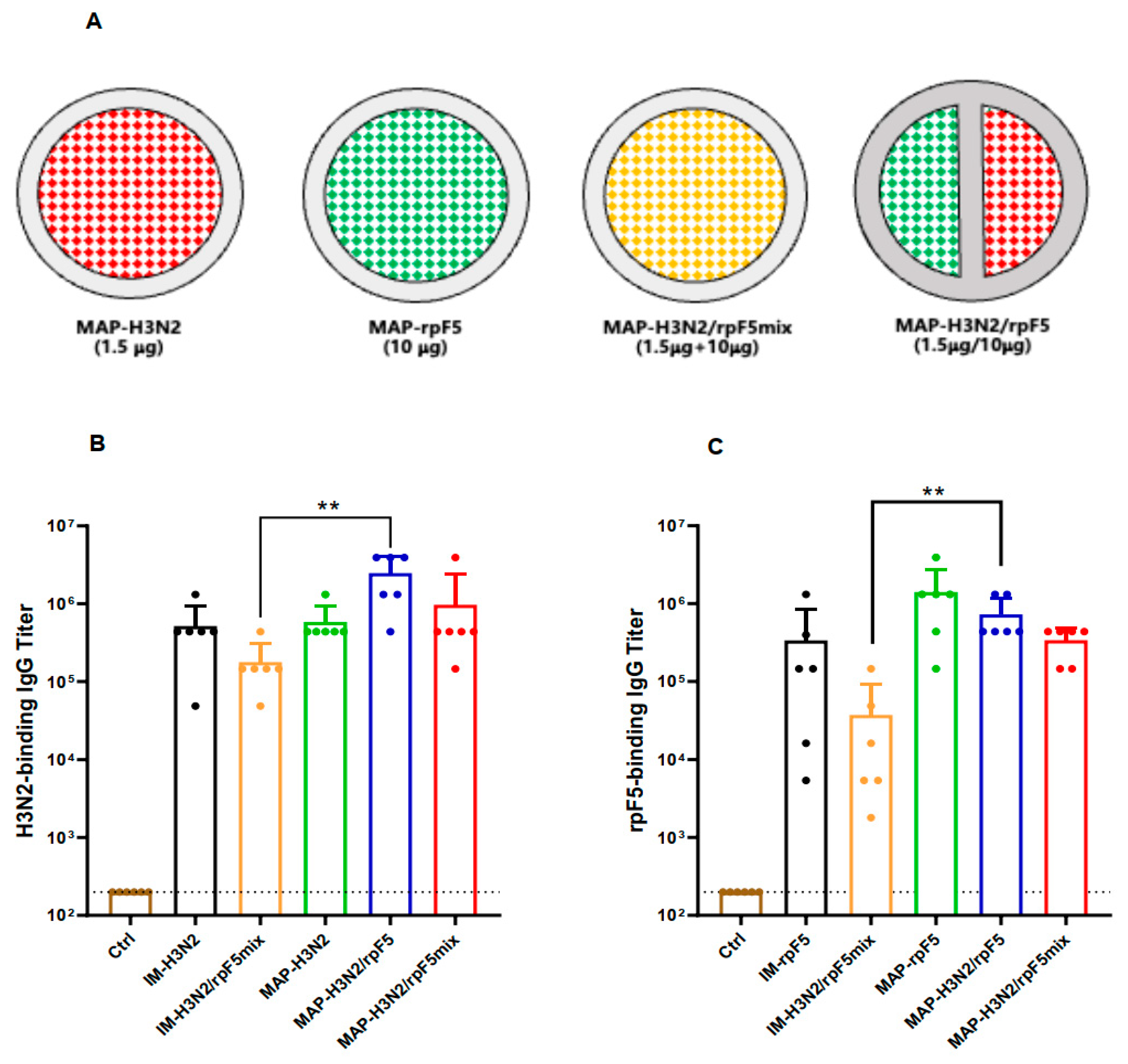

3.4. Partition-Loading Strategy for D-MAP-Based Combo-Vaccine Fabrication

3.5. Immunogenicity Assessment of the MAP-Based Flu–RSV Combo-Vaccine In Vivo

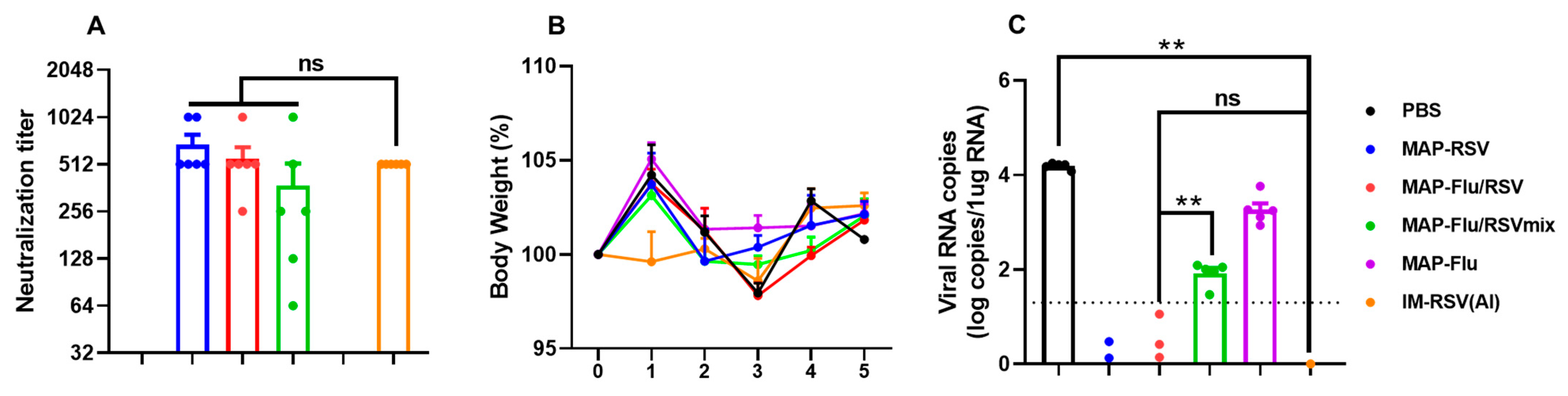

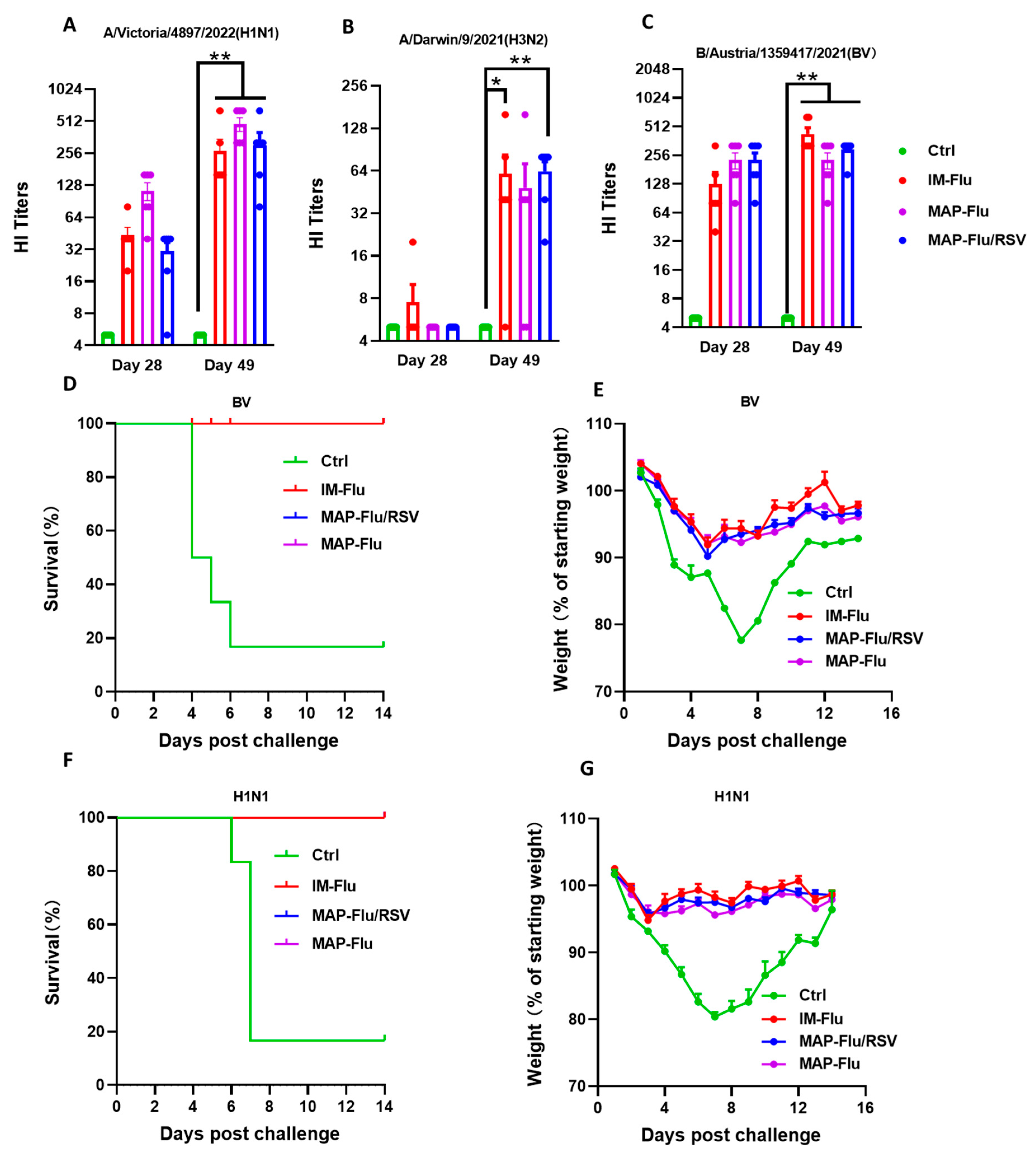

3.6. Protection Efficacy of the MAP-Flu/RSV Combo-Vaccine Against Live Virus Challenge in Mice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lafond, K.E.; Porter, R.M.; Whaley, M.J.; Suizan, Z.; Ran, Z.; Aleem, M.A.; Thapa, B.; Sar, B.; Proschle, V.S.; Peng, Z.; et al. Global burden of influenza-associated lower respiratory tract infections and hospitalizations among adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obando-Pacheco, P.; Justicia-Grande, A.J.; Rivero-Calle, I.; Rodríguez-Tenreiro, C.; Sly, P.; Ramilo, O.; Mejías, A.; Baraldi, E.; Papadopoulos, N.G.; Nair, H.; et al. Respiratory syncytial virus seasonality: A global overview. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 217, 1356–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, M.; Hirve, S.; Bancej, C.; Barr, I.; Baumeister, E.; Caetano, B.; Chittaganpitch, M.; Darmaa, B.; Ellis, J.; Fasce, R.; et al. Human respiratory syncytial virus and influenza seasonality patterns—Early findings from the WHO global respiratory syncytial virus surveillance. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2020, 14, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shichinohe, S.; Watanabe, T. Advances in adjuvanted Influenza vaccines. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topalidou, X.; Kalergis, A.M.; Papazisis, G. Respiratory syncytial virus vaccines: A review of the candidates and the approved vaccines. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- See, K.C. Vaccination for respiratory syncytial virus: A narrative review and primer for clinicians. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhamedova, M.; Wrapp, D.; Shen, C.H.; Gilman, M.S.; Ruckwardt, T.J.; Schramm, C.A.; Ault, L.; Chang, L.; Derrien-Colemyn, A.; Lucas, S.A.; et al. Vaccination with prefusion-stabilized respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein induces genetically and antigenically diverse antibody responses. Immunity 2021, 54, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krarup, A.; Truan, D.; Furmanova-Hollenstein, P.; Bogaert, L.; Bouchier, P.; Bisschop, I.J.M.; Widjojoatmodjo, M.N.; Zahn, R.; Schuitemaker, H.; McLellan, J.S.; et al. A highly stable prefusion RSV F vaccine derived from structural analysis of the fusion mechanism. Nat Commun. 2015, 6, 8143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.X.; Zhong, Y.W.; Zhao, G.; Hou, J.W.; Zhang, S.R.; Wang, B. RSV pre-fusion F protein enhances the G protein antibody and anti-infectious responses. npj Vaccines 2022, 7, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney, J.; Vijayakrishnan, S.; Streetley, J.; Dee, K.; Goldfarb, D.M.; Clarke, M.; Mullin, M.; Carter, S.D.; Bhella, D.; Murcia, P.R. Coinfection by influenza A virus and respiratory syncytial virus produces hybrid virus particles. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 1879–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.H.; Chang, J. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a dual subunit vaccine against respiratory syncytial virus and influenza virus. Immune Netw. 2012, 12, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, T.M.; Jones, L.P.; Tompkins, S.M.; Tripp, R.A. A novel influenza virus hemagglutinin-respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) fusion protein subunit vaccine against influenza and RSV. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 10792–10804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, S.N.T.; Zetner, A.; Hashem, A.M.; Patel, D.; Wu, J.; Gravel, C.; Gao, J.; Zhang, W.; Pfeifle, A.; Tamming, L.; et al. Bivalent vaccines effectively protect mice against influenza A and respiratory syncytial viruses. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2023, 12, 2192821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidor, E. The nature and consequences of intra- and inter-vaccine interference. J. Comp. Pathol. 2007, 137 (Suppl. S1), S62–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, J.; Brenner, R.; Rao, M. Interactions between PRP-T vaccine against Haemophilus influenzae type b and conventional infant vaccines: Lessons for Future Studies of Simultaneous Immunization and Combined Vaccines. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1995, 754, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidor, E.; Hoffenbach, A.; Fletcher, M.A. Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine: Reconstitution of lyophilized PRP-T vaccine with a pertussis-containing pediatric combination vaccine, or a change in the primary series immunization schedule, may modify the serum anti-PRP antibody responses. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2001, 17, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagan, R.; Eskola, J.; Leclerc, C.; Leroy, O. Reduced response to multiple vaccines sharing common protein epitopes that are administered simultaneously to infants. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 2093–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, I.; Bagwe, P.; Gomes, K.B.; Bajaj, L.; Gala, R.; Uddin, M.N.; D’souza, M.J.; Zughaier, S.M. Microneedles: A new generation vaccine delivery system. Micromachines 2021, 12, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.J.; Jeong, S.K.; Roh, D.H.; Kim, D.Y.; Choi, H.-K.; Lee, E.H. A practical guide to the development of microneedle systems—In clinical trials or on the market. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 573, 118778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyraud, N.; Zehrung, D.; Jarrahian, C.; Frivold, C.; Orubu, T.; Giersing, B. Potential use of microarray patches for vaccine delivery in low- and middle-income countries. Vaccine 2019, 37, 4427–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, J.; Henry, S.; Kalluri, H.; McAllister, D.V.; Pewin, W.P.; Prausnitz, M.R. Tolerability, usability and acceptability of dissolving microneedle patch administration in human subjects. Biomaterials 2017, 128, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, N.G.; Paine, M.; Mosley, R.; Henry, S.; McAllister, D.V.; Kalluri, H.; Pewin, W.; Frew, P.M.; Yu, T.; Thornburg, N.J.; et al. The safety, immunogenicity, and acceptability of inactivated influenza vaccine delivered by microneedle patch (TIV-MNP 2015): A randomized, partly blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 1 trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolluru, C.; Gomaa, Y.; Prausnitz, M.R. Development of a thermostable microneedle patch for polio vaccination. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2019, 9, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, S.S.; Richter-Roche, M.; Resch, T.K.; Wang, Y.; Foytich, K.R.; Wang, H.; Mainou, B.A.; Pewin, W.; Lee, J.; Henry, S.; et al. Microneedle patch as a new platform to effectively deliver inactivated polio vaccine and inactivated rotavirus vaccine. npj Vaccines 2022, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, J.C.; Carroll, T.D.; Collins, M.L.; Chen, M.-H.; Fritts, L.; Dutra, J.C.; Rourke, T.L.; Goodson, J.L.; McChesney, M.B.; Prausnitz, M.R.; et al. A microneedle patch for measles and rubella vaccination is immunogenic and protective in infant Rhesus macaques. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Fan, F.; Xu, X.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, B.; Gao, X.-M. A COVID-19 DNA Vaccine Candidate Elicits Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies against Multiple SARS-CoV-2 Variants including the Currently Circulating Omicron BA.5, BF.7, BQ.1 and XBB. Vaccines 2023, 11, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, X.; Pan, Y.; Gong, F.-Y.; Jiang, L.; Kang, L.; et al. Potent Immunogenicity and Broad-Spectrum Protection Potential of Microneedle Array Patch-Based COVID-19 DNA Vaccine Candidates Encoding Dimeric RBD Chimera of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2023, 12, 2202269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, F.; Wu, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; He, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, G.; Xiang, R.; et al. Spatial Segregation Within Dissolving Microneedle Patches Overcomes Antigenic Interference and Enables Potent Bivalent Influenza–RSV Vaccination in Mice. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1213. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121213

Fan F, Wu Y, Lin H, Zhang X, Wang L, He Y, Zhang S, Zhang M, Zhao G, Xiang R, et al. Spatial Segregation Within Dissolving Microneedle Patches Overcomes Antigenic Interference and Enables Potent Bivalent Influenza–RSV Vaccination in Mice. Vaccines. 2025; 13(12):1213. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121213

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Feng, Yehong Wu, Hongzhe Lin, Xin Zhang, Limei Wang, Yue He, Shijie Zhang, Mingju Zhang, Gan Zhao, Rong Xiang, and et al. 2025. "Spatial Segregation Within Dissolving Microneedle Patches Overcomes Antigenic Interference and Enables Potent Bivalent Influenza–RSV Vaccination in Mice" Vaccines 13, no. 12: 1213. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121213

APA StyleFan, F., Wu, Y., Lin, H., Zhang, X., Wang, L., He, Y., Zhang, S., Zhang, M., Zhao, G., Xiang, R., Kang, Y., Chen, M., Li, Z., Guo, Y.-B., Zhou, H., Zhao, C., Wang, M.-C., Gu, J.-Y., Wang, B., & Gao, X.-M. (2025). Spatial Segregation Within Dissolving Microneedle Patches Overcomes Antigenic Interference and Enables Potent Bivalent Influenza–RSV Vaccination in Mice. Vaccines, 13(12), 1213. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121213