Influenza Vaccination and Morbidity Among Sudanese Hajj Pilgrims During the 2025 Hajj

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population and Data Sources

2.3. Data Collection, Categorization, and Processing

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.2. Service Utilization Metrics

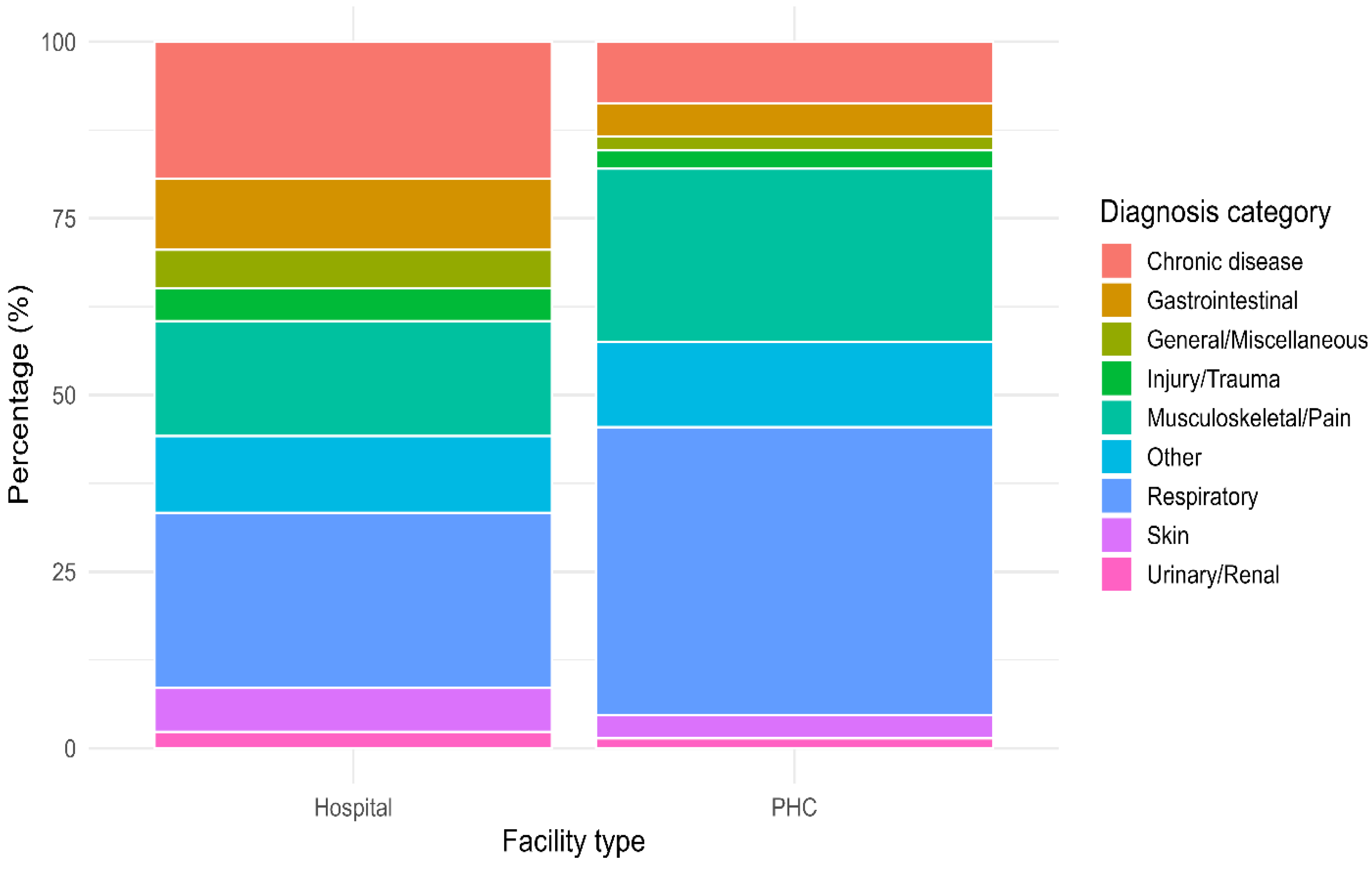

3.3. Distribution of Disease Categories

3.4. Influenza Vaccination and Influenza-like Illness

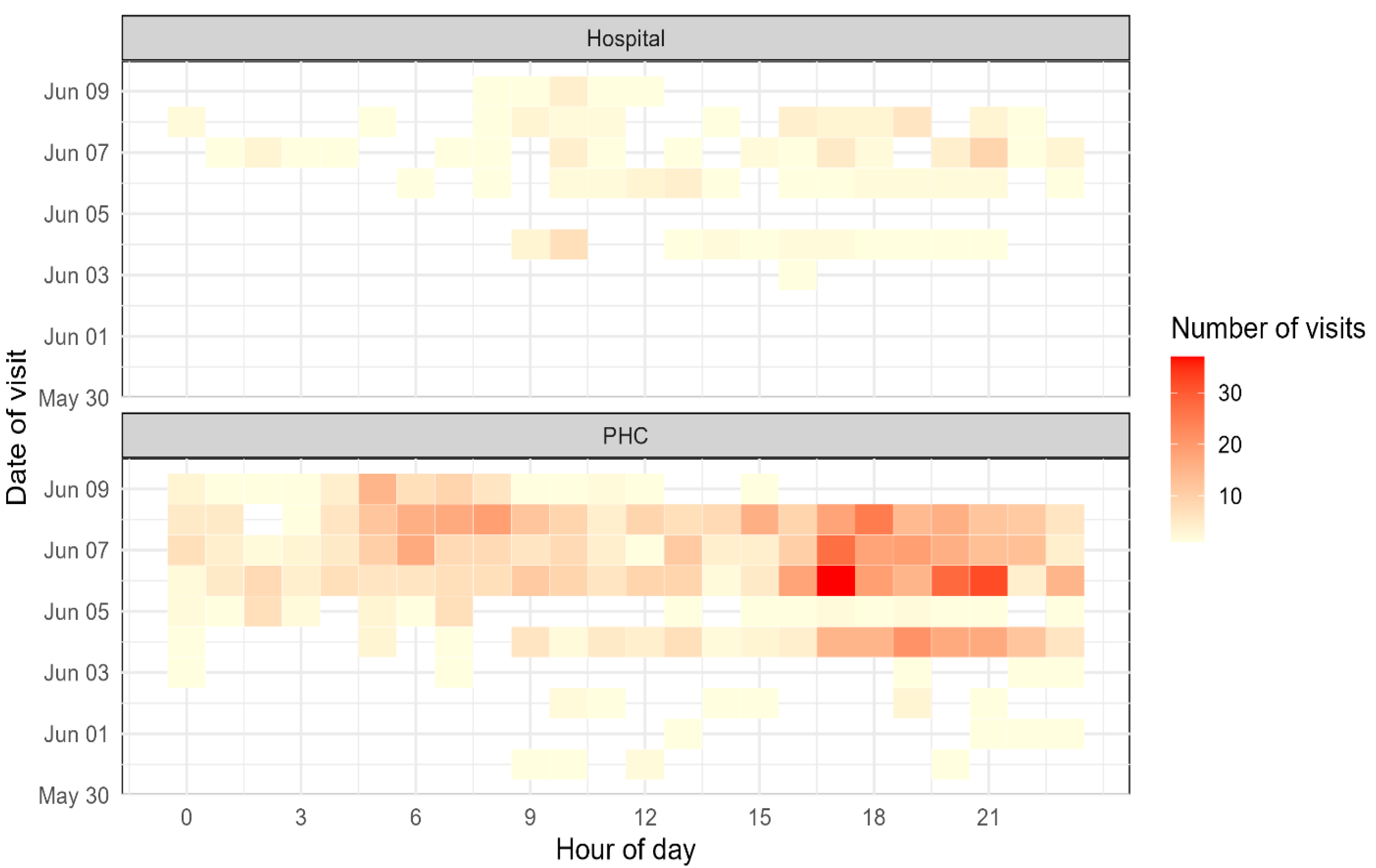

3.5. Temporal Distribution of Visits

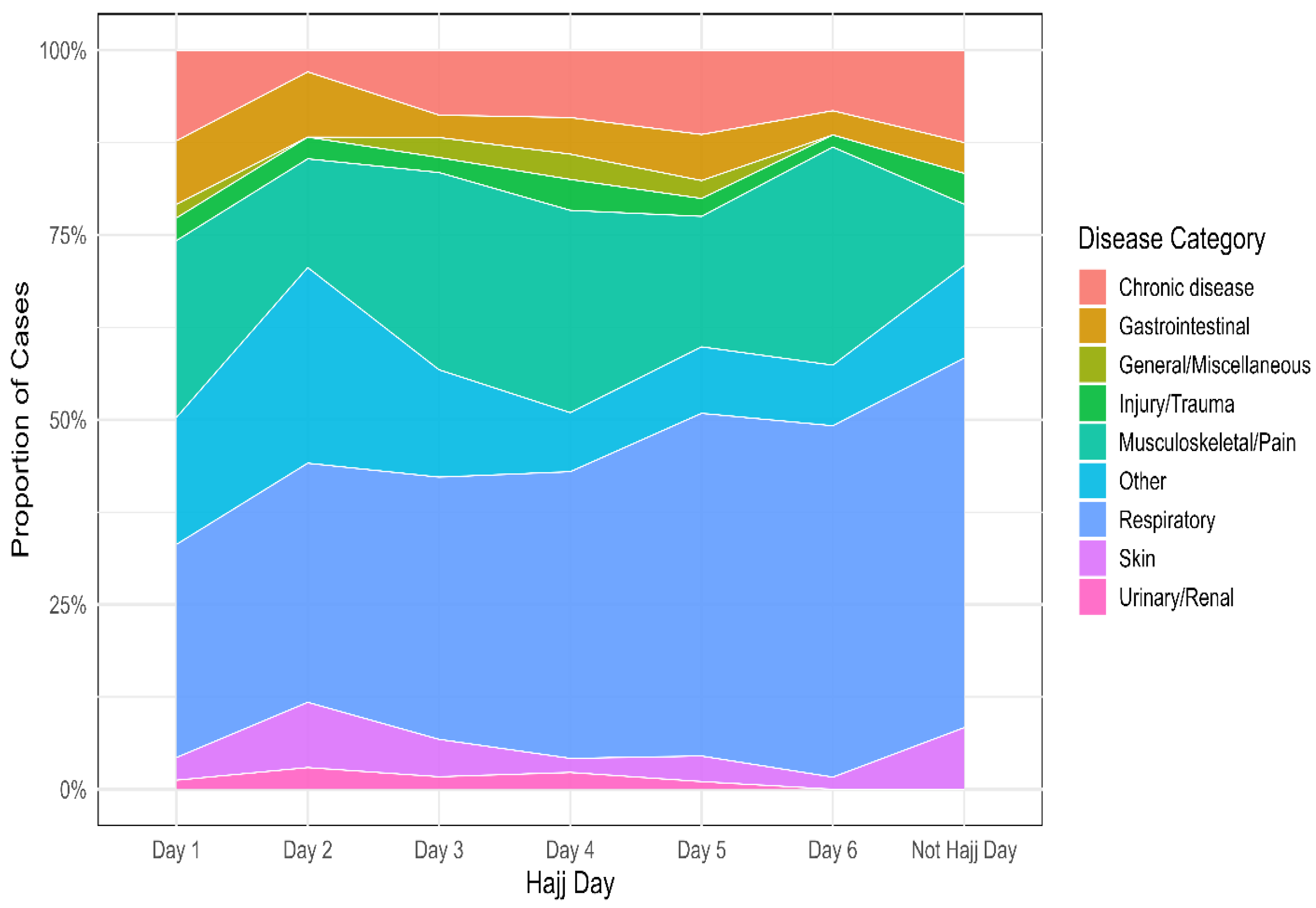

3.6. Temporal Trends of Disease Categories

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yezli, S.; Yassin, Y.M.; Awam, A.H.; Attar, A.A.; Al-Jahdali, E.A.; Alotaibi, B.M. Umrah. An opportunity for mass gatherings health research. Saudi Med. J. 2017, 38, 868. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5556306/ (accessed on 28 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- GASTAT: Total Number of Pilgrims Performing Hajj 1446H (2025) Reaches (1,673,230). Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/w/news/49 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Gautret, P.; Benkouiten, S.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Memish, Z.A. Hajj-associated viral respiratory infections: A systematic review. Travel. Med. Infect. Dis. 2015, 14, 92. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7110587/ (accessed on 27 August 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshahrani, N.Z.; Alarifi, A.M.; Bakhsh, Y.; Dafaa Alla, Z.M.; Assiri, A.M. International Health Regulations (IHR) and the success story of public health preparedness during Hajj in Saudi Arabia. Mass Gather. Med. 2025, 3, 100017. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S3050456225000069 (accessed on 28 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gatrad, A.R.; Sheikh, A. Hajj: Journey of a lifetime. BMJ 2005, 330, 133–137. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/330/7483/133 (accessed on 28 August 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldossari, M.R.; Aljoudi, A.; Celentano, D. Health issues in the hajj pilgrimage: A literature review. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2019, 25, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Q.A.; Arabi, Y.M.; Memish, Z.A. Health risks at the Hajj. Lancet 2006, 367, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddoury, M.A.; Armenian, H.K. Epidemiology of Hajj pilgrimage mortality: Analysis for potential intervention. J. Infect. Public Health 2024, 17, 49–61. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876034123001776 (accessed on 17 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Alrufaidi, K.M.; Nouh, R.M.; Alkhalaf, A.A.; AlGhamdi, N.M.; Alshehri, H.Z.; Alotaibi, A.M.; Almashaykhi, A.O.; AlGhamdi, O.M.; Makhrashi, H.M.; AlGhamdi, S.A.; et al. Prevalence of emergency cases among pilgrims presenting at King Abdulaziz International Airport Health Care Center at Hajj Terminal, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia during Hajj Season, 1440 H—2019. Dialogues Health 2023, 2, 100099. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38515476/ (accessed on 28 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- List of Hospitals in Mina Where Pilgrims Can Receive Medical Services—Hajj Reporters. Available online: https://hajjreporters.com/list-of-hospitals-in-mina-where-pilgrims-can-receive-medical-services/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- MOH News—MOH: 4 Hospitals and 26 Healthcare Centers in Mina Ready to Serve Pilgrims on the Day of At-Tarwiyah. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/News/Pages/News-2022-07-06-001.aspx (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Memish, Z.A.; Stephens, G.M.; Steffen, R.; Ahmed, Q.A. Emergence of medicine for mass gatherings: Lessons from the Hajj. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 56–65. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/action/showFullText?pii=S1473309911703371 (accessed on 28 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Shafi, S.; Booy, R.; Haworth, E.; Rashid, H.; Memish, Z.A. Hajj: Health lessons for mass gatherings. J. Infect. Public Health 2008, 1, 27–32. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876034108000087 (accessed on 17 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Yezli, S.; Elganainy, A.; Awam, A. Strengthening health security at the Hajj mass gatherings: A Harmonised Hajj Health Information System. J. Travel. Med. 2018, 25, tay070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.; Steffen, R.; Rashid, H.; Cabada, M.M.; Memish, Z.A.; Gautret, P.; Sokhna, C.; Sharma, A.; Shlim, D.R.; Leshem, E.; et al. Sacred journeys and pilgrimages: Health risks associated with travels for religious purposes. J. Travel. Med. 2024, 31, taae122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, J.; Thu, M.; Arshad, N.; Van der Putten, M. Mass Gatherings and Public Health: Case Studies from the Hajj to Mecca. Ann. Glob. Health 2017, 83, 386–393. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214999616308062 (accessed on 17 August 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, P.S.; Schwartz, B.; Reeves, M.W.; Gellin, B.G.; Broome, C.V. Intercontinental spread of an epidemic group A Neisseria meningitidis strain. Lancet 1989, 2, 260–263. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2569063/ (accessed on 10 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mushi, A.; Yassin, Y.; Khan, A.; Alotaibi, B.; Parker, S.; Mahomed, O.; Yezli, S. A Longitudinal Study Regarding the Health Profile of the 2017 South African Hajj Pilgrims. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3607. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/7/3607/htm (accessed on 22 October 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Refaey, S.; Amin, M.M.; Roguski, K.; Azziz-Baumgartner, E.; Uyeki, T.M.; Labib, M.; Kandeel, A. Cross-sectional survey and surveillance for influenza viruses and MERS-CoV among Egyptian pilgrims returning from Hajj during 2012–2015. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2017, 11, 57–60. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27603034/ (accessed on 22 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, H.A.; Alluhidan, M.; Almohammed, A.B.; Alfelali, M.; Shaban, R.Z.; Booy, R.; Rashid, H. Epidemiological Differences in Hajj-Acquired Airborne Infections in Pilgrims Arriving from Low and Middle-Income versus High-Income Countries: A Systematised Review. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 418. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2414-6366/8/8/418/htm (accessed on 22 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Global Influenza Programme. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-influenza-programme/surveillance-and-monitoring/case-definitions-for-ili-and-sari?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Alzeer, A.H. Respiratory tract infection during Hajj. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2009, 4, 50–53. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19561924/ (accessed on 21 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Yezli, S.; Yassin, Y.; Mushi, A.; Almuzaini, Y.; Khan, A. Pattern of utilization, disease presentation, and medication prescribing and dispensing at 51 primary healthcare centers during the Hajj mass gathering. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 143. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35115010/ (accessed on 21 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mahomed, O.; Jaffer, M.N.; Parker, S. Morbidity amongst South African Hajj pilgrims in 2023—A retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12622. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-62682-z (accessed on 21 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Memish, Z.A.; Assiri, A.; Turkestani, A.; Yezli, S.; al Masri, M.; Charrel, R.; Drali, T.; Gaudart, J.; Edouard, S.; Parola, P.; et al. Mass gathering and globalization of respiratory pathogens during the 2013 Hajj. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 571.e1–571.e8. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25700892/ (accessed on 27 August 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kattan, W. The state of primary healthcare centers in Saudi Arabia: A regional analysis for 2022. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301918. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0301918 (accessed on 27 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Abd El Ghany, M.; Sharaf, H.; Hill-Cawthorne, G.A. Hajj vaccinations—Facts, challenges, and hope. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 47, 29–37. Available online: https://www.ijidonline.com/action/showFullText?pii=S1201971216310670 (accessed on 21 August 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshamrani, M.; Alhazmi, S.; Alafif, T.; Qadah, T.M.; Aljabri, M.; Al-Eidarous, W.; Alhawsawi, A. From data to insights: A comprehensive analysis of pilgrims stress and fatigue during Hajj using wearable remote sensing systems. J. King Saud Univ. —Comput. Inf. Sci. 2025, 37, 94. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s44443-025-00095-2 (accessed on 27 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Samarkandi, O.; Alamri, F.A.; Alhazmi, J.; Alsaleh, G.S.; Alsehdwei, K.A.; Alabdullatif, L.; Alazmy, W.; Khan, A. Health Risk Behaviors and Associated Factors Among Hajj 2024 Pilgrims: A Multinational Cross-Sectional Study. Risk Manag Heal. Policy 2025, 18, 2233. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12229237/ (accessed on 27 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mirza, A.A.; Al-Sakkaf, M.A.; Mohammed, A.A.; Farooq, M.U.; Al-Ahmadi, Z.A.; Basyuni, M.A. Patterns of Inpatient Admissions during Hajj: Clinical conditions, length of stay and patient outcomes at an advanced care centre in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 34, 781. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6115543/ (accessed on 6 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, N.; Rashid, H.; Parker, S.; Asiri, A.; Memish, Z. Pilgrimage and prevention: Closing meningococcal gaps ahead of Hajj 2025. Mass Gathering Med. 2025, 3, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, S.; Shin, S.; Lapointe-Shaw, L.; Fowler, R.A.; Fralick, M.; Kwan, J.L.; Shojania, K.G.; Tang, T.; Razak, F.; Verma, A.A. Temporal Clustering of Critical Illness Events on Medical Wards. JAMA Intern. Med. 2023, 183, 924. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10334292/ (accessed on 22 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, G.A.; Alghamdi, F.A.; Almatrafi, R.M.; Sadis, A.Y.; Shabkuny, R.A.; Alzahrani, S.A.; Alessa, M.Q.; Hafiz, W.A. The Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Injuries Among Pilgrims During the 2023 Hajj Season: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e56754. Available online: https://cureus.com/articles/219075-the-prevalence-of-musculoskeletal-injuries-among-pilgrims-during-the-2023-hajj-season-a-cross-sectional-study (accessed on 27 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Yezli, S.; Yassin, Y.; Mushi, A.; Aburas, A.; Alabdullatif, L.; Alburayh, M.; Khan, A. Gastrointestinal symptoms and knowledge and practice of pilgrims regarding food and water safety during the 2019 Hajj mass gathering. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1288. Available online: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-11381-9 (accessed on 22 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Alnafisah, R.; Alnasiri, F.; Alzaharni, S.; Alshikhi, I.; Alqahtani, A. Food Safety Practices during Hajj: On-Site Inspections of Food-Serving Establishments. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 480. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10610560/ (accessed on 22 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Alfelali, M.; Barasheed, O.; Tashani, M.; Azeem, M.I.; El Bashir, H.; Memish, Z.A.; Heron, L.; Khandaker, G.; Booy, R.; Rashid, H. Changes in the prevalence of influenza-like illness and influenza vaccine uptake among Hajj pilgrims: A 10-year retrospective analysis of data. Vaccine 2015, 33, 2562–2569. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25887084/ (accessed on 27 August 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Ma, Y.; Ran, J.; Yuan, L.; Zeng, X.; Tan, L.; Chen, L.; Xu, Y.; Li, S.; Huang, T.; et al. Protective Impact of Influenza Vaccination on Healthcare Workers. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1237. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11599008/ (accessed on 27 August 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, A.S.; Rashid, H.; Heywood, A.E. Vaccinations against respiratory tract infections at Hajj. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 115–127. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25682277/ (accessed on 10 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Baklola, M.; Terra, M. AI-powered predictive analytics for crowd health management. Mass Gather. Med. 2024, 2, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baklola, M.; Terra, M.; Alshahrani, N.Z. Building climate-resilient infrastructure for Hajj pilgrims: A path to safer and sustainable pilgrimage. Mass Gather. Med. 2025, 3, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total (n = 1130) N (Column%) | Hospitals (n = 129) N (Row%) | PHCs (n = 1001) N (Row%) | p-Value 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 363 (32.1%) | 37 (10.2%) | 326 (89.8%) | 0.370 |

| Male | 767 (67.9%) | 92 (12.0%) | 675 (88.0%) | ||

| Age group | <40 years | 272 (24.1%) | 31 (11.4%) | 241 (88.6%) | 0.050 |

| 40–59 years | 572 (50.6%) | 59 (10.3%) | 513 (89.7%) | ||

| ≥60 years | 286 (25.3%) | 39 (13.6%) | 247 (86.4%) | ||

| Mean age (±SD) | 49.7 (12.9) | 51.0 (14.2) | 49.6 (12.7) | ||

| Hajj days | Before June 4 (Not Hajj Day) | 24 (2.1%) | 1 (4.2%) | 23 (95.8%) | 0.030 * |

| Day 1—Wed, 4 June | 163 (14.4%) | 22 (13.5%) | 141 (86.5%) | ||

| Day 2—Thu, 5 June | 34 (3.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 34 (100.0%) | ||

| Day 3—Fri, 6 June | 296 (26.2%) | 25 (8.4%) | 271 (91.6%) | ||

| Day 4—Sat, 7 June | 263 (23.3%) | 41 (15.6%) | 222 (84.4%) | ||

| Day 5—Sun, 8 June | 289 (25.6%) | 32 (11.1%) | 257 (88.9%) | ||

| Day 6—Mon, 9 June | 61 (5.4%) | 8 (13.1%) | 53 (86.9%) | ||

| Variable | Total (n = 1130) N (Column%) | Hospitals (n = 129) N (Row%) | PHCs (n = 1001) N (Row%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median visit-to-exam time (minutes, [IQR]) | 5.67 (3.0–9.8) | 7.33 (5.0–12.5) | 5.27 (3.0–9.0) | <0.001 * | |

| Median exam-to-discharge time (minutes, [IQR]) | 2.42 (1.5–4.5) | 4.10 (2.5–6.8) | 2.27 (1.5–4.2) | <0.001 * | |

| Median total clinic time (minutes, [IQR]) | 9.17 (6.5–15.0) | 14.10 (9.0–20.0) | 8.60 (6.0–13.5) | <0.001 * | |

| Percent of time taken to examine the patients | % seen within 15 min | 948 (83.9%) | 106 (82.2%) | 842 (84.1%) | 0.090 |

| % seen within 30 min | 133 (11.8%) | 17 (13.2%) | 116 (11.6%) | ||

| % seen within 60 min | 25 (2.2%) | 3 (2.3%) | 22 (2.2%) | ||

| % seen more than 60 min | 24 (2.1%) | 3 (2.3%) | 21 (2.1%) | ||

| Final Diagnosis | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Acute nasopharyngitis (common cold) | 144 (32.7) |

| Acute upper respiratory infection, unspecified | 82 (18.6) |

| Acute pharyngitis | 80 (18.2) |

| Acute tonsillitis, unspecified | 35 (8.0) |

| Cough | 32 (7.3) |

| Acute sinusitis | 15 (3.4) |

| Acute tonsillitis | 13 (3.0) |

| Conjunctivitis | 6 (1.4) |

| Acute pharyngitis, unspecified | 4 (0.9) |

| Asthma, unspecified | 4 (0.9) |

| Disease of upper respiratory tract, unspecified | 4 (0.9) |

| Acute atopic conjunctivitis | 3 (0.7) |

| Acute upper respiratory infections of multiple/unspecified sites | 3 (0.7) |

| Other diagnoses * | 15 (3.4) |

| Influenza Vaccination | Total N (Column %) | No ILI N (Row%) | ILI N (Row%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not vaccinated | 237 (21.0) | 201 (84.8) | 36 (15.2) | <0.001 1 |

| Vaccinated | 893 (79.0) | 847 (94.8) | 46 (5.2) | |

| Total | 1130 (100) | 1048 (92.7) | 82 (7.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alshahrani, N.Z.; Algethami, M.R.; Albeshry, A.M.; Awan, Z.; AlZhrani, W.; Bugis, O.A.; Alsahafi, A.J.; Rashid, H. Influenza Vaccination and Morbidity Among Sudanese Hajj Pilgrims During the 2025 Hajj. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13111134

Alshahrani NZ, Algethami MR, Albeshry AM, Awan Z, AlZhrani W, Bugis OA, Alsahafi AJ, Rashid H. Influenza Vaccination and Morbidity Among Sudanese Hajj Pilgrims During the 2025 Hajj. Vaccines. 2025; 13(11):1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13111134

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlshahrani, Najim Z., Mohammed R. Algethami, Abdulrahman M. Albeshry, Zuhier Awan, Wael AlZhrani, Osama A. Bugis, Abdullah Jaber Alsahafi, and Harunor Rashid. 2025. "Influenza Vaccination and Morbidity Among Sudanese Hajj Pilgrims During the 2025 Hajj" Vaccines 13, no. 11: 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13111134

APA StyleAlshahrani, N. Z., Algethami, M. R., Albeshry, A. M., Awan, Z., AlZhrani, W., Bugis, O. A., Alsahafi, A. J., & Rashid, H. (2025). Influenza Vaccination and Morbidity Among Sudanese Hajj Pilgrims During the 2025 Hajj. Vaccines, 13(11), 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13111134