Understanding Low Vaccine Uptake in the Context of Public Health in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

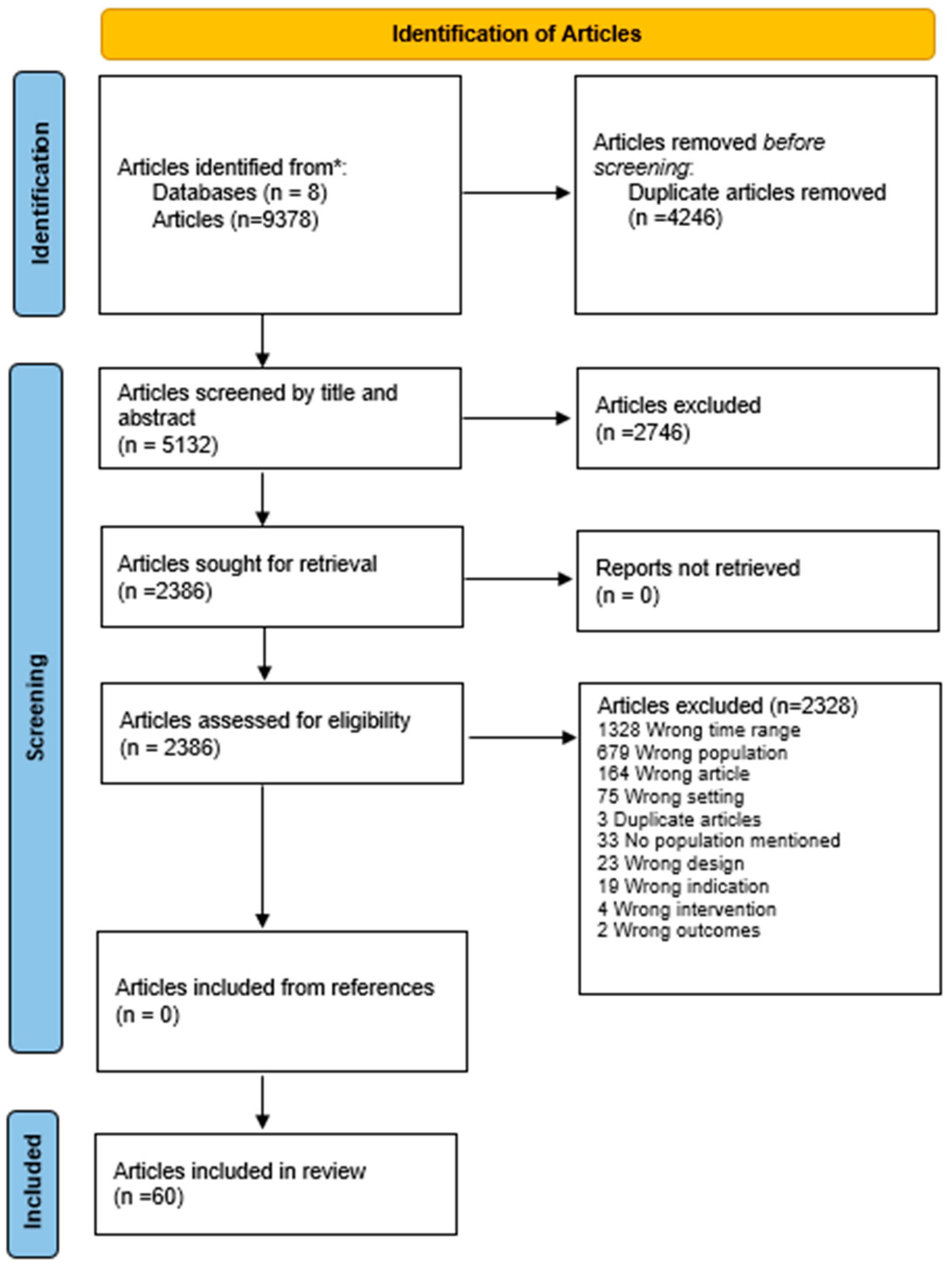

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Defining and Aligning the Objectives and Question

2.2. Developing and Aligning the Inclusion Criteria with the Objectives and Question

2.3. Planned Approach to Evidence Searching, Selection, Data Extraction and Evidence

2.4. Searching the Evidence

2.4.1. Step 1: Initial Search to Identify the List of Relevant Terms

2.4.2. Step 2: Implementation of Search Strategy Based on Identified Terms

2.4.3. Step 3: Hand Searches and Reference List

2.5. Selecting the Evidence

3. Results

3.1. Extracting the Evidence

3.1.1. Qualitative Article Extraction

| Article | Country | Population | Vaccine | Design | Sample Size | Findings | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [56] | USA | Black adolescents | COVID-19 | Qualitative, in-depth interview (IDI) | 28 | - Behaviors and attitudes of church officials and older family members, misinformation from the Internet and peers, personal fears, and skepticism towards the healthcare system and government influenced likelihood of vaccine acceptance | - Tailored messaging to reduce vaccine-related skepticism and address misinformation related to side effects and governmental distrust - Older family members and church officials have the social capital promote vaccination |

| 2 | [57] | USA | Black communities | COVID-19 | Qualitative, rapid review | 61 articles | - Promote vaccine uptake by addressing mistrust, misinformation, and improving access by using trusted communication channels, address historic and experience-based reasons, hold town halls, culturally competent outreach, Black physicians and clinicians partner with community leaders, and trusted and convenient vaccination sites | - HCP * should link with the community through outreach, social media and partnering with community leaders - Distrust is a well-founded response to structural racism; structural inequities and racism are the problem |

| 3 | [58] | USA | Black patients | COVID-19 | Qualitative semi-structured interview (supplemental) | 37 | - Higher prevalence of mistrust about vaccine efficacy, safety, and equitable distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine; PPE and staying home more effective - Fear of racial discrimination of treatment and intended to wait until others received the vaccine first | - Decisions based on discussions with their clinicians and observations of vaccine rollout. - Awareness of historical distrust and the acceptance of new medical intervention can inform efforts to empower Black patients |

| 4 | [59] | USA | -Black Americans: expressed low vaccine intentions -Stakeholders: communities highly impacted by COVID-19 | COVID-19 | Qualitative semi-structured interview | -24 Black Americans -5 Stakeholders | - A “wait-and-see” approach, for side effects and efficacy - Systemic racism: perceived barriers of structural, technology, transportation, medical mistrust of vaccines, healthcare providers, government, health systems, and pharmaceutical companies - Vaccine promotion: strategies acknowledge systemic racism as the root of mistrust, preferred and transparent messaging about side effects, non-medical and medical sites, trusted sources of information, such as Black doctors, researchers, and trusted leaders - Mistrust in providers and the health system: provider’s lack of cultural sensitivity, responsiveness, and competency in practice | - Campaigns: open dialogues with trusted and credible scientists and HCPs *, streamline and maximize process, acknowledge and address mistrust to increase equitable vaccine access by improving confidence and intentions |

| 5 | [60] | USA | AA (African American) parents | HPV (human papillomavirus vaccine) | Qualitative, focus group discussion (FDG) with demographic survey | 18 | - Wanting to be informed, concerns of unfamiliarity, mistrust of HCPs *, pharmaceutical companies, and the government, clarifying risk/benefits, cancer prevention, using straightforward language, provider recommendation - Effective messaging strategies: visuals and narratives with diversity across race, age and gender, clear language on eligibility, transparency on side effects, additional sources of information - Message dissemination: physical locations, word of mouth, and social media | - Promotions: tailored to AA parents and their children to consider building trust and representation in promotional materials - Highlights the importance of culturally tailored messaging with the faces and voices of the intended AA audience to build trust in the community |

| 6 | [61] | USA | AA adults | COVID-19 | Qualitative, IDI | 21 | - VH * determinants: historical mistrust due to government and pharmaceutical companies, unethical research in Black populations, and continued acts of violence by police are a source of tension and distrust of government, knowledge and awareness of the vaccine, social media misinformation, perceptions of HCP *, concerns of side effects, the newness of the vaccine, its necessity and safety, political affiliation -Infodemic exacerbated poor health literacy - Negative experiences with HCP * worsened VH * and validated distrust - Community-based and faith-based health and wellness programs were trusted information sources, enrolled community members for vaccination, organized vaccine clinics at AA churches, and connected community members to HCPs * | - Government needs to commit resources to addressing historical factors and building trust - Partnerships with community members, church leaders and local government to increase community capacity by co-creating solutions including PH * messaging to increase trust and vaccine uptake - Strategies: address relationship with police, increasing communication and collaboration between HCP *, AA, and the government, and government advocating for programs and policies to elevate AA communities |

| 7 | [62] | USA | Black Americans | COVID-19 | Qualitative, FGD | 24 4 focus groups | - Mistrust for the scientific research organizations, medical establishments and pharmaceutical companies based on historical unethical mistreatment, quick development of the vaccine, political environment promoting racial injustice, limited data on short- and long-term effects were reasons for VH *, wrong approach as efforts should be on improving baseline health, confidence lowered by conflicting guidance from the federal, state, and local governments as well as political meddling - Those with VH * expected extremely low vaccine uptake in their social network and a famous Black person would not influence their decision - Increased willingness: safety, efficacy, adverse side effects, transparency in its development, protect families and small children, safely return to work, believed the vaccine would not harm them, reassurance, and recommendations from trusted HCP *; negativity may influence against vaccination - Health concerns: infected by vaccine, risk to immune system with comorbidities | - Build trusted client–HCP * relationships, educate, recommend COVID-19 to those who are VH * - Identify Black influencer to to advocate for the vaccine |

| 8 | [63] | USA | Black Americans | COVID-19 | Qualitative, systematic review | 26 articles | - Mistrust in the government and healthcare systems; 93% of articles had concerns mistrust and VH * - Concerns related to safety, side effect and misconception with COVID-19 vaccine raises ethical questions about health literacy levels and how to it can be improved in Black communities - Unfair distribution of research burdens and benefits can result when Black individuals are represented in the research as a generalization to ethnic minority groups. - Patient–provider relationships can help build trust and reduce skepticism - Community programs that are transparent and factual with officials that have an established relationship with community leaders and that follows up with community members to meet their needs can help to rebuild relationships with Black communities and government and PH * officials | - Healthcare providers and agencies should ethically consider the current drivers and effects of mistrust, adequate inclusion of vulnerable populations in research, improvement of health literacy, and the role of physician in the heath of Black Americans |

| 9 | [64] | USA | Black mothers | All | Qualitative review, blogs, social media posts, and comments that reflect vaccine-critical sentiments, mostly Twitter and Facebook | 249 threads with 311 posts | - Black mothers experience gender and racial bias and rejection of vaccines is a form of governmental power resistance - Black mothers are concerned about vaccines and the organization that promote them and have considered homeschooling as a legal way to avoid vaccines; warn others not to state their objections as they could be more vulnerable, such as to child protective services and to a loss of benefits - Mandatory vaccines in children’s programs may alienate families | - Rather than structural barriers, the under-vaccination can be due to intentional refusal and parental agency - VH * Black mothers view physicians as a potential threat to report families to state agencies; not as consultants or service providers the way privileged families do - Many Black mothers question entities that produce, market, and distribute vaccines - Distrust has been increased by the lack of access to healthcare and vaccines related to COVID-19 |

| 10 | [65] | USA | AA community leaders | COVID-19 | Qualitative, FGD | 18 | - Gaining trust is essential for health communication; trusted messengers are important for disseminating accurate information and promoting vaccination behaviors in AA communities - Messengers, such as student leaders, coaches, and faculty can deliver vaccine-related messages to AA students - Those who obtained their information from less reliable sources had a higher likelihood of misinformation, which led to higher levels of VH *, whereas those who obtained their information from physicians and professionals had a better understanding - Receiving incentives, such as payment, for vaccination caused suspicion - Community leaders recommended recruiting trusted messengers, using football games, homecoming events, and other social events to reach target populations as well as conducting health communication campaigns with open dialogue among stakeholders | - Misinformation and mistrust are the main drivers of VH * in AA communities - Vaccine promotion should include trust building activities, transparency about vaccine development, and community engagement - Interventions regarding communication, accurate messaging, and behavioral change need community support and engagement - To increase trust and confidence, have a combination of key messengers, social events, and use multi-source social media - Tailoring messaging for certain groups, such as by age, may reduce misinformation and promote vaccination in the community |

3.1.2. Quantitative Article Data Extraction

| Number | Article | Country | Population | Vaccine | Design | Sample Size | Findings | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [66] | USA | Black people | COVID-19 | Quantitative abstract - 3-tiered approach to improve vaccine uptake in Black communities - Comparison of percentage of Black people at mass vs. remote vaccination clinics | −24,808 at a mass vaccination clinic −1542 at a remote vaccination clinic | - At a mass clinic where individuals were vaccinated with a first or single dose, 3.7% were Black compared to 44% at the remote clinic | - Multi-tiered community approach: engaging faith leaders with the academic community to disseminate information, culturally representative healthcare professional deliver educational webinars with low-barrier access sites to target Black communities to increase vaccination |

| 2 | [67] | USA | Black Americans (young adults) | COVID-19 | Quantitative, survey | 348 | - Increased willingness: trust in vaccine information, perceived social approval, perception that other Black people were getting vaccinated, skepticism, and perceived control of contracting virus - Decreased willingness: mistrust in vaccine development, government, and vaccine itself | - Trust and normative perceptions impact Black Americans’ intention to get the vaccine |

| 3 | [68] | USA | AA (older) | Flu | Quantitative, survey | 620 | - 1 out of 3 AA 65 and older in South LA has never received the flu vaccine; 49% were vaccinated within the last 12 months - More likely to receive flu vaccine if recommended by their physician -Less likely to be vaccinated: depression symptoms, lived alone, and experienced a lower continuity of care, satisfaction with availability, access, and quality of care | - Flu vaccination rates in underserved older AA impacted by culturally acceptable and accessible sources - Depression is less likely to be treated in AA; screening and treatment for depression may enhance vaccination in underserved older AA - To reduce vaccine-related inequities health professionals should target those living alone, who are isolated, and suffer from depression |

| 4 | [27] | USA | HIV-positive Black adults | COVID-19 | Quantitative, telephone survey | 101 | - Mistrust was significantly associated with higher vaccine and treatment hesitancy - Those with less than a high school education had a higher general mistrust - The most trusted sources were service providers/health professionals followed by local public health officials/agencies, and local government officials - Least trusted sources were the Federal Government and President, followed by social media | - Reception for PH * messages may be increased through healthcare providers and community-based non-political entities |

| 5 | [69] | USA | Black Americans | COVID-19 | Quantitative, survey | 207 | - Not wanting to get vaccinated predictors: weak subjective norms for close social network, mistrust of vaccine, e.g., harm and side effects, living in an area with high socioeconomic vulnerability | - Vaccine confidence is lowered by high levels of mistrust for the vaccine - Attitudes of social networks can be influential in encouraging vaccination - PH * communications should acknowledge historical and current racism and discrimination and be clear and transparent about vaccine safety and efficacy |

| 6 | [70] | USA | Black adults (89.6% US born) | HPV | Quantitative, data from national surveys 2013–2017 | 5246 | - HPV vaccination initiation was ~1.5× higher in US-born compared to foreign-born - Vaccination was associated with being single in men, some college experience, fair/poor health, obstetric/gynecological visit, and pap test; findings suggest health insurance remains crucial for HPV vaccination | - Vaccination rating for Black immigrants may improve with health insurance. - Promotion should be culturally relevant, age-appropriate, and gender-specific for Black immigrants - To improve prevention measures, HCPs * could highlight the need for eligible males to get vaccinated among foreign-born Black populations |

| 7 | [71] | USA | Black Americans | COVID-19 | Quantitative, survey | 2480 | - Police violence concerns were associated with COVID-19 vaccine concerns and worse mental health - Unvaccinated individuals were higher in cultural mistrust, but lower in perceived discrimination, which partially mediated the relationship between COVID-19 race-related concerns and mental health symptoms | - Culturally responsive strategies are needed; individuals may not have the personal agency over factors, such as racism and everyday discrimination, that pose structural barriers to accessing, searching for, and receiving equitable health services |

| 8 | [72] | USA | Black Americans that had not received the COVID-19 vaccine | COVID-19 | Quantitative, experimental intervention using different messaging strategies. Post-test survey. | 739 Black (N = 244), Hispanic (N = 170), white (N = 329) | - Lower VH * was associated with messaging that acknowledged past unethical treat in the medical research of Black Americans and emphasized current measures to prevent medical mistreatment; this was not observed in messaging about the vaccine’s general safety or roles in reducing racial inequities | - PH * vaccine messaging should be tailored to specific concerns and demographic groups |

| 9 | [73] | USA | Young Black Americans (18–30 years) | COVID-19 | Quantitative, online survey | 312 | - Those who had vaccine discussions with their family had a more positive outcome expectancy and favorable injunctive norms | -Promoting positive conversations between young Black people and their families could help increase positive vaccination beliefs and decision-making; families could also be a source of misinformation - Increased knowledge about family communications and health among young Black adults could aid in the development of family and network-based interventions. |

| 10 | [74] | USA | African American (AA) | COVID-19 | Quantitative, preliminary survey, intervention of one of three pro-vaccine messages | 394 | - Self-persuasive narrative had a more positive vaccine belief with higher vaccination intention - Narrative message and the self-persuasion narrative both had the greatest vaccination intention | - Mass media campaigns should include stories about people who changed their minds about the vaccine |

| 11 | [75] | USA | SLE patients (78.4% Black) | COVID-19 | Quantitative abstract survey via mail, Internet, and phone | 598 | - Those VH * were younger, more often Black, less likely to be married, lower income, depressed, less educated, had more Medicare and/or Medicaid, had less trust in the government, doctors, news, lupus advocacy, and support groups, had less general concern for COVID-19, believed in more potential lupus flare ups, lupus-related side effects, and decreased efficacy in lupus - Had received fewer previous flu vaccinations, higher depression, and lower resilience - 66.1% with COVID-19 VH * had a recent flu vaccine | - Flu vaccinations in VH * group show a potential for vaccine receptivity - Outreach led by community leaders and peers should focus on young, Black, depressed individuals with low socioeconomic status |

| 12 | [76] | USA | AA | COVID-19 | Quantitative, survey | 257 | - The odds of being vaccine-resistant were 21× higher in participants aged 18 to 29 compared to 50 and older adults; 7× higher in those with housing insecurity, are less likely to be men, more likely to be employed full-time, less likely to have health insurance, lower total number of comorbidities, more likely to be tobacco smokers, less likely to ever have received a flu shot | - Heath systems and organizations must build rapport and trust in vulnerable populations to reduce disparities in vaccine uptake, related infection, and death, through being transparent about COVID-19 vaccines, community engagement, and diversity in medical professionals |

| 13 | [77] | USA | Black/AA | Childhood immunizations | Quantitative review, data from UW health systems, Google and Google Trend searches; 2015–2020 | University of Wisconsin, Madison serves over 600,000 patients each year | - Child immunization rates in BAA communities are continuously declining - Media review suggests anti-vaccination leaders have increasingly targeted the BAA community with misinformation and skepticism - Main questions BAA parents have including safety and information, such as pros/cons, about vaccines | - Health systems must be assessed for disparities and drivers to effect change; health systems and professionals must look to understand and address the fears increased by anti-vax leaders - Strategies should combat negative media campaigns (anti-vax) and close knowledge gaps - Healthcare organization must fund their communities and public health departments to build trust and decrease disparities |

| 14 | [10] | USA | AA with heart failure (HF) | Influenza (flu) | Quantitative, survey, during 18 February 2017 flu season | 152 | - Predictors of vaccination: 55 and older, increased number of comorbidities, received flu vaccine information and recommendation from HCP *, especially their cardiologists - More patients received flu vaccination information and recommendation from their internists and family physicians than their cardiologists; maybe due to frequency of visits, but all had consulted with their cardiologist at least once | - Physicians have a crucial role in positively influencing their patients’ vaccination behavior; they must be aware of this influence and consistently provide flu vaccine education and recommendation during consultations and outpatient visits - It is recommended that there be standing orders and protocols in the electronic medical record system to allow HCPs *, such as nurses, to recommend the flu vaccine and to vaccinate patients without a direct order from a physician or supervision when an assessment for a true medical contraindication is not needed - Flu vaccination concerns should guide the tailored education of patients, which may improve coverage rate in patients with high-risk conditions |

| 15 | [78] | USA | AA hospitalized with severe COVID-19 infection | COVID-19 | Quantitative abstract, phone survey and data from medical records | 48 | - 66% of the patients would not get the vaccine when available, despite comorbidities. - Reasons for declining: fear of vaccine side effects (61%), distrust of the pharmaceutical companies that make vaccines (58%), and uncertainty about effectiveness (42%) - 75% of the participants were more likely to accept it if their primary care physicians or specialists recommended it; 8% would accept it based on information in TV/radio ads or the Internet | - Education that is focused on patient concerns and direct recommendations from medical providers may increase vaccination coverage in vulnerable populations |

| 16 | [79] | USA | AA hospitalized with COVID-19 infection | COVID-19 | Quantitative, survey post recovery and discharge | 119 | - Higher likelihood of acceptance: male and uninsured - Higher likelihood of declining: patients with congestive heart failure, coronary, artery disease, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension - Major reasons for declining: combination of distrust in efficacy despite research findings and distrust in pharmaceutical companies that produce vaccines (78%), fear of side effects (65%), perceived immunity against re-infection (29%). - 3/10 AA patients who recovered from infection would accept a “safe and effective” COVID-19 vaccine | - Medical providers and community-based advocacy groups should work together to build trust and dispel misconceptions |

| 17 | [80] | USA | Black churchgoers | COVID-19 | Quantitative, pretest survey, intervention with a 1.5h webinar, post-test survey | 220 | - Most of participants personally knew someone who became infected; few were concerned about hospitalization if they became infected. - Many participants: learning facts about COVID-19 was most impactful and hearing from Black physician researchers who were involved in the vaccine’s development -Webinar increased willingness -Willingness was higher in Black males, no age difference -VH * may be reduced in high-risk groups through community academic partnership collaborations to reach Black communities. -May influence likelihood: changes in perceived benefits, susceptibility, and seriousness | - Excellent virtual tools to reach large audiences; during pandemic social interactions restricted - Intervention initiatives could be strengthened through longstanding relationships with the community. |

| 18 | [81] | USA | African American parents | HPV | Quantitative manuscript. pretest, randomly assigned a pamphlet with arguments for vaccination with either a gain-framed or loss-framed message, followed by a post-test | 184 | - Loss-framed messaging with parents that had a low perception of the HPV vaccine efficacy meant that they were more reluctant to vaccinate their children than those who viewed gain-framed messaging - Defense-motivated process and psychological reluctance occurs with loss-framed messaging, which was it was less persuasive than gain-framed messaging | - To prevent reactance and message rejection to tailored messages, people’s perceptions of vaccine efficacy should be assessed before exposure - The relationships between individual perceptions, message framing, and reactance in the context of HPV vaccination is important to understand, particularly among AA, who are disproportionately affected |

| 19 | [82] | USA | AA | COVID-19 | Quantitative, survey | 428 | - 48% of unvaccinated participants reported being VH *; younger, from northeastern US, Republican political affiliation, and religion other than Christianity or atheist | - Large amount of variance in the likelihood to get vaccinated for COVID-19 in VH * AA |

| 20 | [83] | USA | Older adults (AA 80.5%) | Pneumonia | Quantitative, pre-test survey, intervention Pharmacists’ Pneumonia Prevention Program (PPPP); 4 domains (1) pharmacists and pharmacies, (2) vaccination, (3) pneumococcal disease, and (4) physicians, followed by post -test survey, 3-month post intervention survey | 190 | - 21% completely agreed with the statement that the pneumococcal vaccine would prevent pneumonia at baseline; this more than doubled following the program, but returned to baseline after 3 months - 16% trusted pharmacists as immunizers at baseline; nearly half of participants trusted a pharmacist to provide them with a vaccination at post-test, and 27% did 3 months after the program -Trust in pharmacists remained lower than physicians throughout the study | - Individuals have many encounters with healthcare throughout their lives that may influence their beliefs; therefore, altering beliefs may require sustained efforts - Pharmacists and seniors’ centers partnering can be an effective model for community engagement; should consider support for pharmacist’s educational services |

| 21 | [84] | USA | Black Americans | COVID-19 | Quantitative, survey | 1040, matched 2010 US census demographics | - Black Americans had higher levels of VH *; medical trust decreased VH * - Health officials and media risk conflating medical trust, conspiracy thinking, and demographics when seeking to understand perceptions about the COVID-19 vaccine | - Community engagement and dialogue may help promote COVID-19 vaccine acceptance - Structural racism likely the cause of racial immunization disparities |

| 22 | [85] | USA | Black adults | COVID-19 | Quantitative, phone survey | 350 | - 48.9% of Black adults in Arkansas were not COVID-19 vaccine hesitant - 22.4% were very hesitant, 14% somewhat, and 14.7% a little hesitant; hesitancy was 1.70× greater for Black adults who experienced a COVID-19 related death of a close friend/family member, 2.61× greater in those who reported discrimination with police or in the courts, and hesitancy was negatively associated with age | - Among Black adults, there may be a link between COVID-19 VH * and racial discrimination in the criminal justice system - Further research is needed to determine if there is a causal relationship between death caused by COVID-19 and VH * |

| 23 | [86] | USA | Black Americans | COVID-19 | Quantitative, survey online or by phone, measured at first and second wave | 889 | - Trust in information sources is associated with vaccination beliefs - Differences in trust do not account for the differences in vaccination beliefs by race - Race influenced the relationships between trust in Trump and PH * officials and agencies and vaccination beliefs; effects of trusting these sources on COVID-19 vaccine-related beliefs are less among Black participants; trust in these sources is less consequential to their pro-vaccination belief. - Some sources are more likely to be trusted by Black Americans, such as social media; trust in certain sources is associated with lower VH * | - Beliefs can mediate the association between vaccination intention and race, moving the focus from intention to beliefs (VH *) - The observed relationship between vaccination beliefs and race is not explained by trust in information sources alone - Trusted sources could be used to mitigate the effects of the misinformation and to communicate pro-vaccine information |

| 24 | [87] | USA | Black Americans who were eligible for but had not received COVID-19 | COVID-19 | Quantitative, survey | 1278 | - Black Americans’ vaccination intention was independently and interactively affected by the social norms - The norms of all Americans are a decision basis for Black Americans to make decisions regarding COVID-19 vaccination - Social norms of an ethnic group predicted of vaccination intention and could be a potential group to target for interventions | - Practices of comparing and contrasting racial differences in COVID-19 vaccination rates and interventions using strong social norms for all Americans to mobilize Black Americans should be carried out cautiously - Identifying an influential reference group other than a close social network is meaningful and informative for promoting COVID-19 vaccination among Black Americans - Lower vaccination intention among those with perceived strong social norms for all Americans may be due to perceived herd immunity, giving a false sense of protection due to high vaccination and infection rates in the society while Black Americans who were hesitant from the beginning may be even more resistant due to a perception that the vaccine is unnecessary |

3.1.3. Mixed Methods Data Extraction

| Number | Article | Country | Population | Vaccine | Design | Sample Size | Findings | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [88] | USA | AA (African Americans) youths | All vaccines | Mixed methods protocol Phase (1) qualitative IDI (in-depth interview) to assess (2) quantitative, based on assessment (3) quantitative assessment of intervention—expected completion 2023 | Phase 1 and 2: (N/A). Phase 3: (4 clinics and 120 AA youths) | - An intervention that has the potential for PH * impact emphasizes youth autonomy and decision-making; interventions that leverage existing infrastructures increase the likelihood of their transferability - Tablet-based interventions with tailored messaging for youths, including motivational interviewing, text reminders, and with rural context, can be designed to reduce HCP * burden with consideration to environmental and practice limitations | - Researching and creating effective interventions that target AA youths can provide information about VH * and potentially inform effort by practitioners and providers |

| 2 | [89] | UK | African ancestry with HIV | COVID-19 | Mixed methods questionnaire with Likert scale and free text, poster | 540 from 9 sites | - Unvaccinated participants more concerned about side effects and what is in vaccine, such as microchips and materials from pigs or fetuses - Persuade individuals to vaccinate with informed choice through full discussions on trial data and full disclosure of results, 100% efficacy against COVID-19, more data on long-term effects, such as fertility, choice of vaccine, mandatory, such as for travel, and a single dose - Concerns include bioweapon technology, irreversibility altering DNA, medical history, and religious concerns based on what is in the vaccine | - High COVID-19 vaccine uptake was found; those not vaccinated had high levels of concerns and low vaccination necessity - Community engagement can help address health inequities, vaccine concerns, and misinformation |

| 3 | [90] | USA | AA undergoing smoking cessation treatment | COVID-19 | Mixed methods, secondary analysis of data from ongoing RCT (random control trial), questionnaire with closed and open questions | 172 | - Few participants mentions a physician’s opinion as being influential to their decision get vaccinated for COVID-19; most mentioned information that would be helpful in decisions: efficacy, safety, side effects, initial outcomes of others - Participants with low vaccine intentions had concerns about vaccine development, trustworthiness, and efficacy | - PC and the medical system need a concerted effort to gain trust in AA communities; carry a high burden of COVID-19 |

| 4 | [91] | USA | AA smoking cessation | COVID-19 | Mixed method, survey with open and closed questions, baseline and follow-up, poster abstract | 172 | - 36% not willing to take the COVID-19 vaccine if freely available, most common reasons are a lack of trust in the vaccine, uncertainty due to it being rushed, unsure what was in it, not enough studies, and not taking vaccines in general, including flu shot - Willingness to get vaccinated for COVID-19, most common reasons were protection, to feel safe, as well as worry of getting sick or dying from infection | - High rates of HV could prolong higher negative impacts from COVID-19 on AA |

| 5 | [92] | USA | Black Americans | COVID-19 | Mixed methods, survey, interviews, focus group discussions (FGD) | 183 surveys, 30 interviews, 8 FGD (n = 49) | - Potential factors affecting access perceived to be transportation barriers; no Internet access for relevant COVID-19 information or to register for appointments; Internet could be difficult for some elderly people to navigate; healthcare system is complex and can be difficult to navigate - Factors affecting vaccine acceptance were perceived as communal safety, peer pressure, fear fatigue of worrying for oneself and others, mandated pressures, individual’s perceived risk of infection and severity of outcome, belief in other effective means of protection; vaccine confidence in safety and efficacy associated with increased willingness to get vaccinated, those familiar with vaccine immunology were hopeful that more information would increase others’ willingness; more willing to get vaccinated once with observed effectiveness in others - Factors associated with vaccine resistance: deep-rooted belief, e.g., religious, conspiracies theories and myths, distrust in the government, and level of trustworthiness of healthcare system and medical community - Improve vaccination rates: community outreach and navigators, vaccine endorsement (scientists, community leaders, clinicians, peers), timely information in multiple formats, community vaccination cites (churches, community centers), testimonials by trusted professional, HCPs * from community as frontline advocates | - VH * changes with situational context and knowledge - Could reduce accessibility issues with community collaborations to establish community-based clinics and by employing community navigators and coordinators |

| 6 | [93] | USA | AA | COVID-19 | Mixed methods, questionnaire with open and closed questions | 203 | - VH * mainly due to mistrust in the healthcare system, other reasons: the speed of vaccine developments, confidence in current health and lack of information, mistrust in the healthcare system and government - Non-hesitance was mainly due to already being vaccinated, the protection of self and others, required by school or work - Some stated that encouragements from trusted individuals may change their minds about being vaccinated | - HCP * and pharmacists can contribute to improving confidence and decreasing vaccine hesitancy |

| 7 | [94] | USA | Black Americans who expressed VH | COVID-19 | Mixed methods, IDI, qualitative thematic analysis and quantitative code application | 18 | - All stated lack of trust in the government regarding information dissemination and doubt in approach to healthcare - Most were concerned that the vaccine was rushed, stated more time and data were the most important intervention to increase their willingness to be vaccinated; other factors included seeing friends and family vaccinated, but celebrities and politicians would not sway them; other factors included being able to go out to events with friends and family, personalized medical advice from a physician, more information about people who were vaccinated, and emphasis on protecting friends and family - Many had a distrust for vaccines in general, fear of long- and short-term side effects, and question those distributing vaccines to Black communities caring about them based on historical medical mistreatment - Physicians were the most frequent sources of information; other sources were newspapers, television, church, virtual town halls, hospital websites, family and friends, and a few used social media | - 1/3 of those that expressed VH * had become vaccinated by the end of the study, potentially indicating fluidity in opinions regarding VH * - Prioritizing vaccine acceptance in communities most susceptible to infections helps protect the larger population and, thus, individuals nationwide |

3.1.4. Commentary Data Extraction

| Number | Article | Country | Population | Vaccine | Design | Sample Size | Findings/Key Statements | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [95] | USA | Black women | COVID-19 and influenza (Flu) | Commentary | N/A | - The healthcare industry must directly engage to foster authentic relationships and rebuild trust as the potentially lethal combination of COVID-19 and influenza create the possibility of a “twindemic” - Consistently low flu vaccinations in Black women foreshadows concerns with COVID-19 vaccination; top flu vaccine concerns were adverse effects, safety, and effectiveness - Low vaccine uptake in Black women not unexpected based on historical mistrust in healthcare system from Tuskegee syphilis experiments to underrepresentation of Black people in vaccine trials - Healthcare should be view as preventative of negative health impacts of the SDOH * | - Black people will not have equitable access to cures without recruiting more Black people in research and vaccine trails - Mistakes of the past are doomed to repeat without community empowerment |

| 2 | [96] | USA | Black people | COVID-19 | Commentary | N/A | - Everyday racism, such as denying pain, treatments withheld, and misdiagnosis, are ignored when citing historical mistrust at the cause for mistrust in the HC system - Trust is critical; Black women prefer Black physicians, even waiting months for appointments - Concordant health messaging is important | - Vaccine rollout needs Black physicians and investigators at the forefront - Black health leaders need to give public health messages - Black scientists relate to the needs of communities |

| 3 | [97] | Canada | Black people | COVID-19 | Commentary | N/A | - Politicization of the vaccine, lack of culturally relevant information and accurate and timely race-based data, poor public health coordination response between levels of government added barriers and contributed to mistrust - To address VH *, engage Black community leaders in all steps of vaccine development, distribution, and monitoring to improve transparency through an internal assets-based approach - Increase trust and transparency due to vaccine’s quick development including risks of side effects, efficacy, such as for children and pregnant women, address misinformation and conspiracy theorists that exploit historical injustices, ensure diverse representation in vaccine trials - Ensure clinics in rural communities since travel can be timely and costly - Long-term support to address needs and concerns after vaccination | - Strategies must address concerns and fears of racism in vaccine development and distribution |

| 4 | [98] | USA | Black people | COVID-19 | Commentary | N/A | - The difference in experiences of Black and white Americans with the healthcare system may account for differences in trust in the government and medical establishment involved in vaccine development - Reasons to fear and mistrust based on medical history - Be transparent to combat mistrust, comprehensive communication, acknowledge uncertainty, increase accessibility, ensure vaccination is not cost-prohibitive - PH * officials and medical professionals should communicate the safety and efficacy of vaccines due to high levels of suspicion of pharmaceutical companies—transparency about delays and side effects would help build trust | - Black Americans have had worse health outcomes than white Americans across many conditions for decades—COVID-19 can be used to eliminate disparities, restore trust by listening to most disadvantaged, acknowledging reasons for mistrust, and maintaining transparency for racial justice |

| 5 | [99] | USA | Black Americans | COVID-19 | Commentary | N/A | - A Black intensive care nurse was the first American to receive the vaccine with the hope of inspiring others - Increased uptake attributed to outreach by health leaders, medics, and faith and community organizations, such as through livestream town halls; community support, peer influence, and testimonials make a difference. - Increased access and availability with more locations within the community, like barbershops and hair salons, especially helps those of lower socioeconomic levels to minimize travel - Medical professionals should remind patients of the importance of vaccines - Mistrust drives VH *, those who were against are starting to consider it, misinformation that targeted Black communities caused a plateau, but increased when people saw pain and suffering, and vaccines were mandatory—policies should require all populations to be vaccinated for PH * | N/A |

| 6 | [100] | USA | Black Americans | COVID-19 | Commentary | N/A | - Acknowledge historical mistreatment by medical establishments, the trauma it caused, and health disparities from unconscious bias and racism, and do not blame Black Americans themselves - Mutual and transparent conversations between physicians and Black patients to listen to concerns and acknowledge VH * | - Create health equity and anti-racism initiatives, including misinformation, availability, accessibility, roundtables to bring together institutions and community leaders, educational committee to develop education with consistent and accessible messaging to target vulnerable populations, provide transportation, assisting with neighborhood and mobile vaccination distribution |

| 7 | [2] | Canada | Black people | COVID-19 | Commentary | N/A | - VH * due to misinformation of literacy gaps and medical distrust and structural racism - Afrocentric health promotion and counselling improved uptake of flu and COVID-19 vaccines and center on clients’ values and perspective - Clinicians can bridge gaps and improve vaccine uptake with communication framework - Outreach and confronting anti-Black racism to increase vaccine confidence can be improved with Black-led partnerships between trusted stakeholders and healthcare - Clinicians should support patients to navigate complex systems, state data on the number of vaccinated Black clients and Black scientist’s contributions, emphasize the importance of population-wide coverage, and offer accurate, current information to high-risk Black patients about access - Provided greater access and/or be on priority lists | |

| 8 | [101] | USA | AA (African Americans) | Flu and COVID-19 | Review | - Low flu vaccine uptake is at least partly from bias in medicine causing mistrust, safety concerns, and barriers to access, exacerbating adverse health outcomes - Policy initiative and robust education to build trust in the health benefits of the flu vaccine and ultimately to build trust in the COVID-19 vaccine when it becomes available - Increased vaccine trust and confidence, including perceived health benefits and recommending it to others, is associated with increasing racial fairness - Must provide evidence-based information on the COVID-19 vaccine to support acceptance once available - Mobile vaccination programs can rapidly disseminate and increase access in hard-to-reach communities; unified service providers can increase mobile infrastructure | - To increase COVID-19 vaccine uptake, establish new initiatives to build trust and support evidence-based medicine - To support health equity, address racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities -AA voices must identify potential barriers in Black communities and overcome historical mistrust in clinical trials | |

| 9 | [102] | USA | AA | COVID-19 | Review | N/A | - Increased risk for severe illness from COVID-19 due to comorbidities, and SDOH *, such as lower health literacy and educational attainment, essential workers, inadequate healthcare access and utilization, living in crowded housing, and lower income reduces the likelihood of following methods for mitigating risk recommended by health officials - Parents are buffers/filters for their children due to social dispositions, and racial socialization related to racial identity and systemic racism and medical abuse is well known; mistrust is racially socialized from integrated experiences and trauma, such as the impact of others being mistreated in healthcare; child witnessing parent may prevent them from seeking care - Peer relationships (including family) can increase susceptibility to conspiracy theories and have been associated with increased VH *, such as that the vaccine has malicious intent against people of color - Have expressed hesitancy about the vaccine safety, effectiveness, and speed of development - Online misinformation target AA communities; the source cannot always be determined; others may masquerade as AA - Vaccine uptake is influenced by events, such as the Black Lives Matter movement, and the impact of the pandemic, such as disruptions to work and school, which increased anxieties | - Service providers need to act as partners in assessing, advocating, and implementing interventions for disparities while addressing the SDOH * |

| 10 | [103] | USA | Black community | COVID-19 | Commentary | N/A | - Have the highest rate of individuals that are unsure or will never get vaccinated; concern that VH * may further heath disparities - Distrust in government and medical professionals is justified by historical racism in medical research - Systemic and structural barriers include distribution, access, availability, and transportation - Black men are underrepresented in the medical profession, and they are critical for building trust; build trust by increasing the number of Black nurses, physician, dentists, pharmacists, and allied professionals - Access to health information is key to educating and dispelling false information on social media that can influence decision-making and hesitancy; build trust by providing information with clear, lay language to understand health related information and answer questions through online and physically locations, such as barbershops, churches, mosques, and other trusted community-based organizations | - The Black community should be vaccinated, and medical professionals must do more to create trust and improve care |

| 11 | [104] | USA | Black Physicians | COVID-19 | Commentary | N/A | - Racial inequities in vaccine rollout echo the disparities experienced throughout the pandemic with less vaccines going to Black residents - Mistrust has been brought up as a factor against low vaccine uptake in Black communities; a commonly proposed solution is positioning Black physicians and investigators at the forefront to provide racially concordant messaging and build trust; this circumvents rather than deals with the issues of mistrust - Black physicians have a greater burden then their non-Black counterparts as they earnestly work to encourage vaccination in Black communities; they themselves are underrepresented in medicine because of racism - First-hand experiences and collective experiences of family, community, and history are not simply reflected in the physician– Black patient relationship but in the institution’s relationship to the Black community; the institution cannot substitute an individual Black physician’s trustworthiness for its own | - Placing Black physicians as the solution deflect the responsibility of institutions and generates systemic problems for those already overburdened; solutions to present racial inequities must not exacerbate the problem in the future |

| 12 | [105] | USA | Black people | COVID-19 | Commentary | N/A | - A physician, researcher, epidemiologist, and Black woman had COVID-19 when it first came out, and they reviewed the immunology, listened to interviews, and reviewed the data before getting vaccinated, still with uncertainty; experiences of structural racism overpowered medical education - If systemic racism cannot be understood, it will be difficult to understand VH * in the Black community - Service providers need to acknowledge wrongs and failure to gain trust based on historical and everyday racism, and undergo training to do better | - The government and medical community should work towards quick and equitable distribution to build trust |

| 13 | [106] | USA | Black patients and physicians | COVID-19 | Commentary | N/A | - Fewer providers that look like them due to the healthcare infrastructure may lower intention due to general lack of trust - Being a Black physician does not remove concerns of mistreatment and distrust in the system; VH * still exists - Fears driven from historical medical experiments and stories passed down through generations are the basis for distrust in the healthcare system - When healthcare leaders recommended mass vaccination to Black communities, could cause fears of further being tested on before the general population - Focus should be educating the population rather, not pressuring an individual - Community and healthcare leaders need to leverage tools, like social media. to offer advice - Every physician must counsel each patient and address concerns about vaccination - Questions about the novelty of the technologies in the COVID-19 vaccine must be answered, with full disclosure to earn trust | - Properly convey truth that the vaccine will not be tested on vulnerable populations and is administered safely for their benefit; this may be emphasized by witnessing the safe administration of the vaccine on societal leaders, such as healthcare professionals and politicians - Vaccine transparency is a short-term solution, more healthcare workers are needed that represent their best interests, understand their experiences, are from their neighborhoods, and are as diverse as they are |

| 14 | [107] | USA | Black people | COVID-19 | Commentary | N/A | - Historical mistreatment and current concern causes distrust of vaccines and institutions - Trusted messengers are crucial to protecting the community, e.g., pastors - A proposed framework to build trust and acceptance includes understanding history and context, creating partnerships with shared responsibility and power, listening and empathy, engaging pastors as trusted messengers, and co-creation of solutions with faith leaders and their community, governments, and institutions to create sustainable, long-term change | - Pastors and others in the faith community must work with governments and institutions to build trust, inform, facilitate discussions, and create measurable improvements - Sustainable efforts for lasting and impactful change are needed to establish, stronger collaboration, build relationships - Possible vaccine solutions may be initiated by focusing on issues important to the community |

| 15 | [108] | USA | AA hemodialysis patients | COVID-19 Influenza (flu) | letter to the editor | 90 (83% AA) | - Half of the hemodialysis patient survey participants were willing to get the COVID-19 vaccinations; influenza vaccination was associated with willingness - Previous personal history of COVID-19 was not associated with accepting the vaccine, low willingness to receive the vaccine may pre-exist the pandemic based on interactions with HCP *, low access, VH *, low clinical trial participation, and cost - HCP * must collaborate with trusted partners to build trust, identify the best alternatives to improve quality of care, and to help create targeting messaging around COVID-19 - VH * increased by not enough safety and efficacy information | - Patient education is essential to increase vaccine uptake and combat misinformation |

| 16 | [109] | USA | Black Americans | COVID-19 | Commentary | N/A | - Black HCPs * role in providing care for their patients and their communities - Exploitation and persecution of Black Americans by the US healthcare system has affected Black communities for generations; COVID-19 gives an opportunity for the healthcare system to begin to make amends for historical injustices and discrimination - Strategies to address VH *: acknowledge past and present injustices based in policies, all clinicians and trainees have iterative cultural competency training with a focus on the SDOH * for health equity, transparency in risks and benefits and accountability of vaccine delivery, developing messages that are educational, informative and acknowledge as well as addressed apprehension about safety and side effects in a culturally sensitive way, partner with trusted sources, such as faith-based organizations, political advocacy groups, and grassroots organizations to engage Black communities in a personal and culturally sensitive way, increase access by reaching communities when and where they prefer to be vaccinated | - Address VH * by building an equitable mechanism through genuine communication, thoughtful partnerships, relevant messaging, and removing barriers |

| 17 | [110] | USA | African Americans and others in marginalized communities | COVID-19 | Commentary | N/A | - Differences in the rate of vaccine uptake may be explained by external factors, such as structural racism - Healthcare systems must mitigate factors that prevent making informed decisions about COVID-19 vaccination; scientists, researchers, and physicians must understand factors outside of the person that explain decisions and behaviors related to vaccination - Historical basis for mistrust and cynicism towards health professionals due to historical events, such as the Tuskegee experiment, cannot be overlooked by healthcare policy makers - Being Black should not be a predictor for VH *; further analysis into the ways that social and structural determinants explain COVID-19 vaccination related choices is needed | - Methods of addressing health disparities that existed before, and were exacerbated by the pandemic include repairing mistrust, increasing AA healthcare workers, including in the community, providing training and incorporating culture-based healing practices into services and research, developing and assessing the cultural competence of healthcare workers, mobilizing community workers to provide COVID-19 information about safety and efficacy to gatherings, such as in churches and recreation areas, community engagement research, and ensuring protection from unethical research practices including informed consent |

| 18 | [111] | USA | Black people | COVID-19 | Commentary | N/A | - Distrust is deeply rooted in centuries of racist exploitation by American physicians and researchers, not only in Tuskegee - The main responsibility of overcoming racism is not on Black people themselves - Pharmaceutical companies can build trust by ensuring that that a vaccine is not submitted for approval until it has been thoroughly assessed for efficacy and safety, especially due to the politicization of vaccine trials, and that trial participants will receive medical care if injured as a result of an experimental vaccine, as well as informed consent, including all aspects of the trial, to maximize transparency; participants have the right to expect that Black communities will have fair access to results | - The COVID-19 vaccine’s success will depend on trust that it is safe and effective and the trustworthiness of organizations offering them. - Efforts must have bidirectional collaborations with communication and learning grounded in the grassroots involvement of organizations and individuals trusted by Black community members and leaders |

| 19 | [112] | USA | Black people | COVID-19 | Commentary | N/A | - Asking why Black people do not trust HCPs * pathologizes them as having something wrong rather than the conditions around them; it ignores the roles health institutions have in distrust, and implies that many of their health-related problems would go away if they were more trusting - Women are often primarily tasked with care work; those who are the most vulnerable, such as Black women, care for others, often with low wages and little protection, while simultaneously needing care - Asking questions about vaccine safety and efficacy is prudent and diligent, rather than hesitant | - Reluctance is justifiable and using an explanatory narrative may overvalue the role of trust; it should be a part, but not all of, the conversation. |

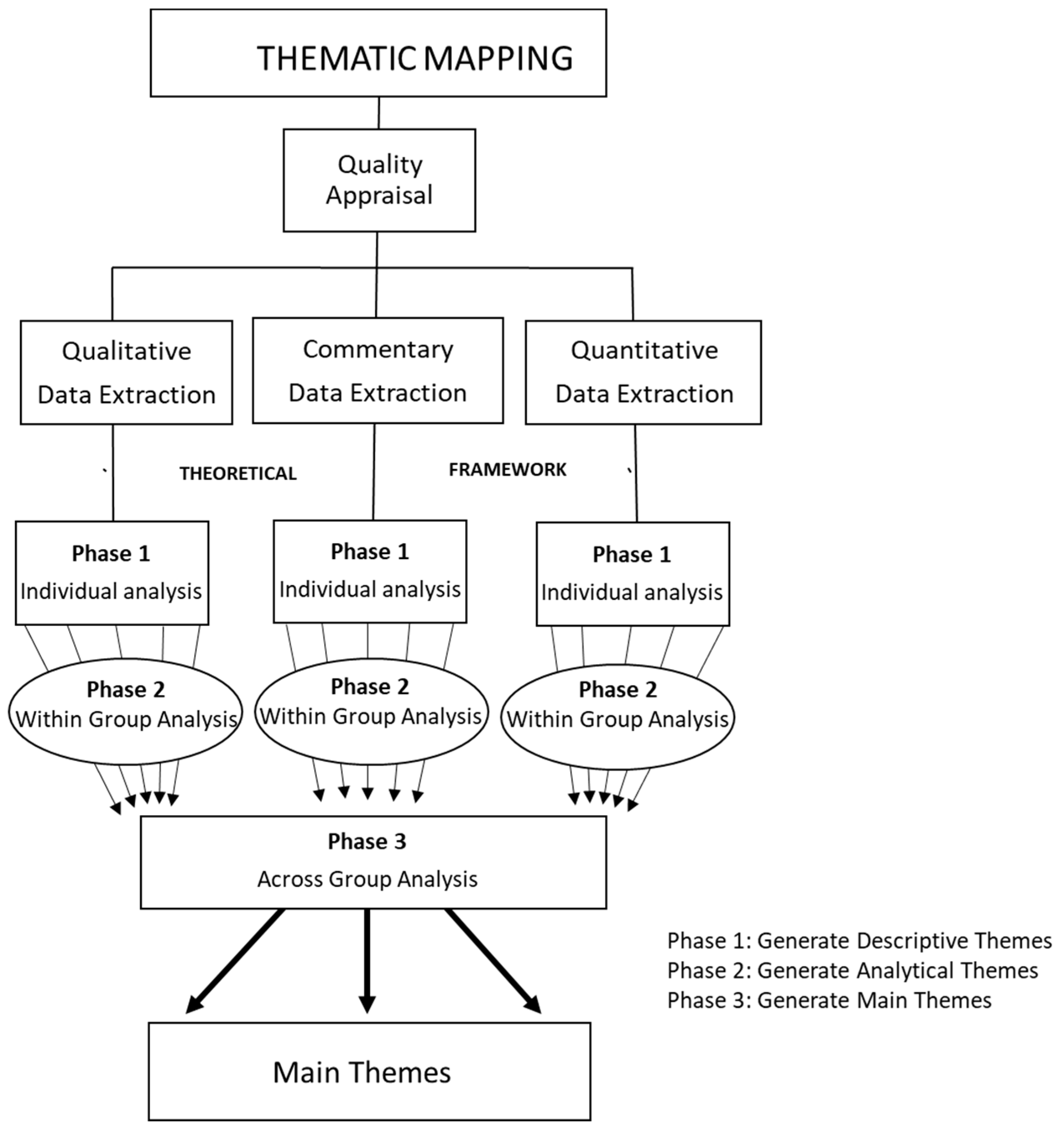

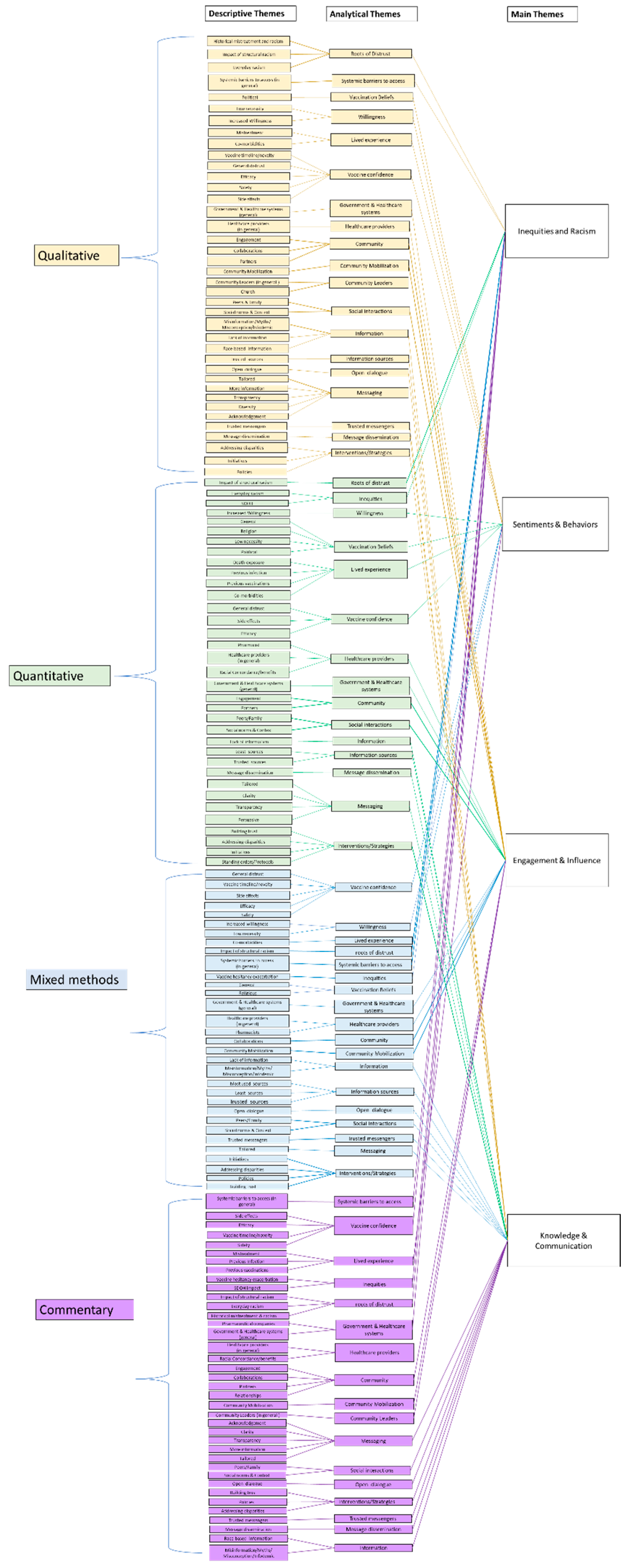

3.2. Analyzing the Evidence

3.2.1. Thematic Mapping Diagram

3.2.2. Phase (1): Individual Study Analysis

3.2.3. Phase (2): Within-Group Analysis

3.2.4. Phase (3): Across-Group Analysis

3.3. Presentation of the Evidence

3.4. Theme 1: Inequities and Racism

3.4.1. Inequities

3.4.2. Vaccine Hesitancy Exacerbation

3.4.3. Social Determinants of Health

3.4.4. Social Determinant of Health Impact

3.4.5. Roots of Distrust

3.4.6. Historical Mistreatment and Racism

3.4.7. Impact of Structural Racism

3.4.8. Everyday Racism

3.4.9. Racial Burden

3.4.10. Concordance

3.4.11. Systemic Barriers to Access

3.4.12. Systemic Barriers to Access (In General)

3.5. Theme 2: Sentiments and Behaviors

3.5.1. Willingness

Low Necessity

Increased Willingness

3.5.2. Vaccination Beliefs

General

Religion

Political

3.5.3. Lived Experience

Mistreatment

Death Exposure

Previous Infection

Previous Vaccinations

Comorbidities

3.5.4. Vaccine Confidence

General Distrust

Vaccine Timeline/Novelty

Side Effects

Efficacy

Safety

3.6. Theme 3: Engagement and Influence

3.6.1. Government and Healthcare Systems

3.6.2. Government and Healthcare Systems (In General)

3.6.3. Pharmaceutical Companies

3.6.4. Healthcare Providers

3.6.5. Healthcare Providers (HCP) (In General)

3.6.6. Pharmacists

3.6.7. Racial Concordance/Benefits

3.6.8. Community

3.6.9. Engagement

3.6.10. Collaborations

3.6.11. Partners

3.6.12. Relationships

3.6.13. Community Mobilization

3.6.14. Community Mobilization

3.6.15. Community Leaders

3.6.16. Community Leaders (In General)

3.6.17. Church

3.6.18. Social Interactions

3.6.19. Peers/Family

3.6.20. Social Norms and Context

3.7. Theme 4: Knowledge and Communication

3.7.1. Information

3.7.2. Lack of Information

3.7.3. Race-Based Information

3.7.4. Misinformation/Myths/Misconception/Infodemic

3.7.5. Information Sources

Most Used Sources

Least Trusted

Trusted Sources

3.7.6. Open Dialogue

Open Dialogue

Messaging

Diversity

Clarity

Acknowledgement

Transparency

3.7.7. More Information

3.7.8. Tailored Messaging

3.7.9. Persuasive Messaging

3.7.10. Trusted Messengers

3.7.11. Trusted Messengers

3.7.12. Message Dissemination

Message Dissemination

Interventions/Strategies

Building Trust

Policies

Addressing Disparities

Standing Orders/Protocols

Initiatives

Gaps in the Literature

4. Discussion

4.1. Macro/Systemic

4.2. Meso/Organizational

4.3. Micro/Individual

5. Conclusions

Strengths and Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

- American Samoa

- Andorra

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Aruba

- Australia

- Austria

- Bahamas, The

- Bahrain

- Barbados

- Belgium

- Bermuda

- British Virgin Islands

- Brunei Darussalam

- Canada

- Cayman Islands

- Channel Islands

- Chile

- Croatia

- Curacao

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Denmark

- Estonia

- Faroe Islands

- Finland

- France

- French Polynesia

- Germany

- Gibraltar

- Greece

- Greenland

- Guam

- Guyana

- Hong Kong Sar, China

- Hungary

- Iceland

- Ireland

- Isle of Man

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea, Rep.

- Kuwait

- Latvia

- Liechtenstein

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Macao Sar, China

- Malta

- Monaco

- Nauru

- Netherlands

- New Caledonia

- New Zealand

- Northern Mariana Islands

- Norway

- Oman

- Panama

- Poland

- Portugal

- Puerto Rico

- Qatar

- Romania

- San Marino

- Saudi Arabia

- Seychelles

- Singapore

- Sint Maarten (Dutch Part)

- Slovak Republic

- Slovenia

- Spain

- St. Kitts And Nevis

- St. Martin (French Part)

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Trinidad And Tobago

- Turks And Caicos Islands

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uruguay

- Virgin Islands (U.S.)

References

- The Canadian COVID-19 Genomics Network (CanCOGeN). Understanding the Impact of COVID-19 on Black Canadians. Genome Canada, 26 February 2021.

- Eissa, A.; Lofters, A.; Akor, N.; Prescod, C.; Nnorom, O. Increasing SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Rates among Black People in Canada. CMAJ 2021, 193, E1220–E1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. COVID-19 Vaccine Willingness among Canadian Population Groups. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2021001/article/00011-eng.htm (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Kricorian, K.; Turner, K. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Beliefs among Black and Hispanic Americans. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. CPHO Sunday Edition: The Impact of COVID-19 on Racialized Communities. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/news/2021/02/cpho-sunday-edition-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-racialized-communities.html (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Dalsania, A.K.; Fastiggi, M.J.; Kahlam, A.; Shah, R.; Patel, K.; Shiau, S.; Rokicki, S.; DallaPiazza, M. The Relationship Between Social Determinants of Health and Racial Disparities in COVID-19 Mortality. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2022, 9, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryden, O.; Nnorom, O. Time to Dismantle Systemic Anti-Black Racism in Medicine in Canada. CMAJ 2021, 193, E55–E57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.; Edjoc, R.; Atchessi, N.; Striha, M.; Gabrani-Juma, I.; Dawson, T. COVID-19: A Case for the Collection of Race Data in Canada and Abroad. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2021, 47, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafiq, M.; Elharake, J.A.; Malik, A.A.; McFadden, S.M.; Aguolu, O.G.; Omer, S.B. COVID-19 Sources of Information, Knowledge, and Preventive Behaviors Among the US Adult Population. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2021, 27, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olanipekun, T.; Effoe, V.S.; Olanipekun, O.; Igbinomwanhia, E.; Kola-Kehinde, O.; Fotzeu, C.; Bakinde, N.; Harris, R. Factors Influencing the Uptake of Influenza Vaccination in African American Patients with Heart Failure: Findings from a Large Urban Public Hospital. Heart Lung 2020, 49, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, H.A.; Malik, F.; Shapiro, E.; Omer, S.B.; Frew, P.M. Message Framing Strategies to Increase Influenza Immunization Uptake Among Pregnant African American Women. Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 1639–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A.; Lam, K.; Danielli, S.; Ashrafian, H.; Darzi, A. COVID-19 Vaccinations among Black Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) Groups: Learning the Lessons from Influenza. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE). Report of the Sage Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Available online: https://thecompassforsbc.org/sbcc-tools/report-sage-working-group-vaccine-hesitancy (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Dubé, E.; Laberge, C.; Guay, M.; Bramadat, P.; Roy, R.; Bettinger, J.A. Vaccine Hesitancy. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2013, 9, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koons, C. When Nurses Refuse to Get Vaccinated. Bloomberg, 28 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagavathula, A.S.; Aldhaleei, W.A.; Rahmani, J.; Mahabadi, M.A.; Bandari, D.K. Knowledge and Perceptions of COVID-19 Among Health Care Workers: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, E.A.; Wu, J.W. Vaccine Confidence in the Time of COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Immunization Coverage. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/immunization-coverage (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Mayo Clinic. Herd Immunity and COVID-19: What You Need to Know. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/in-depth/herd-immunity-and-coronavirus/art-20486808 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Government of Canada (GC). Canadian Immunization Guide: Introduction. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/canadian-immunization-guide/introduction.html (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Oku, A.; Oyo-Ita, A.; Glenton, C.; Fretheim, A.; Ames, H.; Muloliwa, A.; Kaufman, J.; Hill, S.; Cliff, J.; Cartier, Y.; et al. Communication Strategies to Promote the Uptake of Childhood Vaccination in Nigeria: A Systematic Map. Glob. Health Action 2016, 9, 30337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Overview, History, and How It Works | CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/ensuringsafety/history/index.html (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Nguyen, T.C.; Gathecha, E.; Kauffman, R.; Wright, S.; Harris, C.M. Healthcare Distrust among Hospitalised Black Patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Postgrad. Med. J. 2022, 98, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.C.; Dubey, V. Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy: Clinical Guidance for Primary Care Physicians Working with Parents. Can. Fam. Physician 2019, 65, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). COVID-19 Global Risk Communication and Community Engagement Strategy—Interim Guidance. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/covid-19-global-risk-communication-and-community-engagement-strategy (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Bogart, L.M.; Ojikutu, B.O.; Tyagi, K.; Klein, D.J.; Mutchler, M.G.; Dong, L.; Lawrence, S.J.; Thomas, D.R.; Kellman, S. COVID-19 Related Medical Mistrust, Health Impacts, and Potential Vaccine Hesitancy Among Black Americans Living With HIV. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2021, 86, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waisel, D.B. Vulnerable Populations in Healthcare. Curr. Opin. Anesthesiol. 2013, 26, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office for National Statistics. Coronavirus and Vaccine Hesitancy, Great Britain. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/bulletins/coronavirusandvaccinehesitancygreatbritain/31marchto25april (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.; Colquhoun, H.; Kastner, M.; Levac, D.; Ng, C.; Sharpe, J.P.; Wilson, K.; et al. A Scoping Review on the Conduct and Reporting of Scoping Reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockwood, C.; dos Santos, K.B.; Pap, R. Practical Guidance for Knowledge Synthesis: Scoping Review Methods. Asian Nurs. Res. 2019, 13, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews—JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis—JBI Global Wiki. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, A.; Hodson, A.; Pearce, J.M. A Rapid Systematic Review of Factors Influencing COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake in Minority Ethnic Groups in the UK. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, M.R.; Alzubaidi, M.S.; Shah, U.; Abd-Alrazaq, A.A.; Shah, Z. A Scoping Review to Find Out Worldwide COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Underlying Determinants. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, F.; Najeeb, H.; Moeed, A.; Naeem, U.; Asghar, M.S.; Chughtai, N.U.; Yousaf, Z.; Seboka, B.T.; Ullah, I.; Lin, C.-Y.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the United States: A Systematic Review. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 770985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomoni, M.G.; Di Valerio, Z.; Gabrielli, E.; Montalti, M.; Tedesco, D.; Guaraldi, F.; Gori, D. Hesitant or Not Hesitant? A Systematic Review on Global COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Different Populations. Vaccines 2021, 9, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thota, A.B. PROTOCOL: Scoping Review of Interventions to Increase Vaccination Uptake for Racial and Ethnic Minorities and Indigenous Population Groups Living in High-Income Countries. 2022. Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/osf/t3ykz (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Hankivsky, O. INTERSECTIONALITY 101. Available online: https://docplayer.net/4773103-Intersectionality-101-olena-hankivsky-phd.html (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- Qureshi, I.; Gogoi, M.; Al-Oraibi, A.; Wobi, F.; Pan, D.; Martin, C.A.; Chaloner, J.; Woolf, K.; Pareek, M.; Nellums, L.B. Intersectionality and Developing Evidence-Based Policy. Lancet 2022, 399, 355–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golden, S.D.; Earp, J.A.L. Social Ecological Approaches to Individuals and Their Contexts: Twenty Years of Health Education & Behavior Health Promotion Interventions. Health Educ. Behav. 2012, 39, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.; Gottlieb, L. The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Rep. 2014, 129, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. Part I—Systemic Racism and Discrimination in the Defence Team: Origins and Current Reality. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/corporate/reports-publications/mnd-advisory-panel-systemic-racism-discrimination-final-report-jan-2022/part-i-systemic-racism.html (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Kumar, D.; Chandra, R.; Mathur, M.; Samdariya, S.; Kapoor, N. Vaccine Hesitancy: Understanding Better to Address Better. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2016, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Guardian. Covid: UK Woman Who Was First in World to Receive Vaccine Has Second Dose. The Guardian, 8 December 2020.

- Annett, C. Inequities in COVID-19 Health Outcomes: The Need for Race- and Ethnicity-Based Data. Available online: https://hillnotes.ca/2020/12/08/inequities-in-covid-19-health-outcomes-the-need-for-race-and-ethnicity-based-data/ (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Government of Ontario. Ontario’s Regulatory Registry. Available online: https://www.ontariocanada.com/registry/view.do?postingId=32967&language=en (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etowa, J.; Demeke, J.; Abrha, G.; Worku, F.; Ajiboye, W.; Beauchamp, S.; Taiwo, I.; Pascal, D.; Ghose, B. Social Determinants of the Disproportionately Higher Rates of COVID-19 Infection among African Caribbean and Black (ACB) Population: A Systematic Review Protocol. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 11, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, L.H.; Kagina, B.M.; Ndze, V.N.; Hussey, G.D.; Wiysonge, C.S. Improving Vaccination Uptake among Adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.; Schmidt, B.-M.; Sambala, E.Z.; Swartz, A.; Colvin, C.J.; Leon, N.; Wiysonge, C.S. Factors That Influence Parents’ and Informal Caregivers’ Views and Practices Regarding Routine Childhood Vaccination: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, M.O.; Taggart, T.; Galbraith-Gyan, K.V.; Nyhan, K. Black Caribbean Emerging Adults: A Systematic Review of Religion and Health. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budhwani, H.; Maycock, T.; Murrell, W.; Simpson, T. COVID-19 Vaccine Sentiments Among African American or Black Adolescents in Rural Alabama. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 69, 1041–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dada, D.; Djiometio, J.N.; McFadden, S.M.; Demeke, J.; Vlahov, D.; Wilton, L.; Wang, M.; Nelson, L.E. Strategies That Promote Equity in COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake for Black Communities: A Review. J. Urban Health 2022, 99, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon, G.D.; Zulman, D.; Baratta, J.; Brown-Johnson, C.; Garcia, R.; Hollis, T.; Cox, J. Black Patient Perceptions of COVID-19 Vaccine, Treatment, and Testing. Ann. Fam. Med. 2022, 20, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.; Bogart, L.M.; Gandhi, P.; Aboagye, J.B.; Ryan, S.; Serwanga, R.; Ojikutu, B.O. A Qualitative Study of COVID-19 Vaccine Intentions and Mistrust in Black Americans: Recommendations for Vaccine Dissemination and Uptake. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lama, Y.; Qin, Y.; Nan, X.; Knott, C.; Adebamowo, C.; Ntiri, S.O.; Wang, M.Q. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Acceptability and Campaign Message Preferences Among African American Parents: A Qualitative Study. J. Canc. Educ. 2022, 37, 1691–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majee, W.; Anakwe, A.; Onyeaka, K.; Harvey, I.S. The Past Is so Present: Understanding COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among African American Adults Using Qualitative Data. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2023, 10, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momplaisir, F.; Haynes, N.; Nkwihoreze, H.; Nelson, M.; Werner, R.M.; Jemmott, J. Understanding Drivers of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Blacks. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 1784–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restrepo, N.; Krouse, H.J. COVID-19 Disparities and Vaccine Hesitancy in Black Americans: What Ethical Lessons Can Be Learned? Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022, 166, 1147–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, C.; Reich, J.A. Black Mothers and Vaccine Refusal: Gendered Racism, Healthcare, and the State. Gend. Soc. 2022, 36, 525–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Qiao, S.; McKeever, B.; Olatosi, B.; Li, X. “Where the Truth Really Lies”: Listening to Voices from African American Communities in the Southern States about COVID-19 Vaccine Information and Communication. medRxiv 2022, arXiv:2022.03.21.22272728. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Mutakabbir, J.C.; Simiyu, B.; Walker, R.E.; Christian, R.L.; Dayo, Y.; Maxam, M. Leveraging Black Pharmacists to Promote Equity in COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake within Black Communities: A Framework for Researchers and Clinicians. JACCP J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2022, 5, 887–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubuchon, K.; Stock, M.; Post, S.; Hagerman, C. Black Young Adults’ COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions: The Role of Trust and Health Cognitions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2022, 56, S59. [Google Scholar]

- Bazargan, M.; Wisseh, C.; Adinkrah, E.; Ameli, H.; Santana, D.; Cobb, S.; Assari, S. Influenza Vaccination among Underserved African-American Older Adults. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, e2160894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogart, L.M.; Dong, L.; Gandhi, P.; Klein, D.J.; Smith, T.L.; Ryan, S.; Ojikutu, B.O. COVID-19 Vaccine Intentions and Mistrust in a National Sample of Black Americans. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2022, 113, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofie, L.E.; Tailor, H.D.; Lee, M.H.; Xu, L. HPV Vaccination Uptake among Foreign-Born Blacks in the US: Insights from the National Health Interview Survey 2013–2017. Cancer Causes Control 2022, 33, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cokley, K.; Krueger, N.; Cunningham, S.R.; Burlew, K.; Hall, S.; Harris, K.; Castelin, S.; Coleman, C. The COVID-19/Racial Injustice Syndemic and Mental Health among Black Americans: The Roles of General and Race-Related COVID Worry, Cultural Mistrust, and Perceived Discrimination. J. Community Psychol. 2022, 50, 2542–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanani, L.Y.; Franz, B. An Experimental Study of the Effects of Messaging Strategies on Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy among Black Americans. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 27, 101792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, D.B.; Mason, N.; Occa, A. Young African Americans’ Communication with Family Members About COVID-19: Impact on Vaccination Intention and Implications for Health Communication Interventions. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2022, 9, 1550–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Green, M.C. Reducing COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among African Americans: The Effects of Narratives, Character’s Self-Persuasion, and Trust in Science. J. Behav. Med. 2022, 46, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]