Did Italy Really Need Compulsory Vaccination against COVID-19 for Healthcare Workers? Results of a Survey in a Centre for Maternal and Child Health

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- personal and professional characteristics (demographic data, professional profile, working environment with high or no infectious risk, state of health);

- perception of the pandemic (main sources of information, personal opinion of the pandemic’s impact on the population);

- anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (perception of risks and benefits of vaccination, reasons for choosing or refusing to join the vaccination campaign);

- optional section (impact of the pandemic on the personal sphere).

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- İkiışık, H.; Sezerol, M.A.; Taşçı, Y.; Maral, I. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and related factors among primary healthcare workers in a district of Istanbul: A cross-sectional study from Turkey. Fam. Med. Community Health 2022, 10, e001430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Tomietto, M.; Simonetti, V.; Comparcini, D.; Stefanizzi, P.; Cicolini, G. A large cross-sectional survey of COVID-19 vaccination willingness amongst healthcare students and professionals: Reveals generational patterns. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Navin, M.C.; Oberleitner, L.M.S.; Lucia, V.C.; Ozdych, M.; Afonso, N.; Kennedy, R.H.; Keil, H.; Wu, L.; Mathew, T.A. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Healthcare Personnel Who Generally Accept Vaccines. J. Community Health 2022, 47, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyerdahl, L.W.; Dielen, S.; Nguyen, T.; Van Riet, C.; Kattumana, T.; Simas, C.; Vandaele, N.; Vandamme, A.M.; Vandermeulen, C.; Giles-Vernick, T.; et al. Doubt at the core: Unspoken vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers. Lancet Regional Health 2022, 12, 100289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth-Manikowski, S.M.; Swirsky, E.S.; Gandhi, R.; Piscitello, G. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy among health care workers, communication, and policy-making. Am. J. Infect. Control 2022, 50, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudasama, R.V.; Khunti, K.; Ekezie, W.C.; Pareek, M.; Zaccardi, F.; Gillies, C.L.; Seidu, S.; Davies, M.J.; Chudasama, Y.V. COVID-19 vaccine uptake and hesitancy opinions from frontline health care and social care workers: Survey data from 37 countries. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2022, 16, 102361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zürcher, K.; Mugglin, C.; Egger, M.; Müller, S.; Fluri, M.; Bolick, L.; Piso, R.J.; Hoffmann, M.; Fenner, L. Vaccination willingness for COVID-19 among healthcare workers: A cross-sectional survey in a Swiss canton. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2021, 151, w30061. [Google Scholar]

- Tomietto, M.; Comparcini, D.; Simonetti, V.; Papappicco, C.A.M.; Stefanizzi, P.; Mercuri, M.; Cicolini, G. Attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination in the nursing profession: Validation of the Italian version of the VAX scale and descriptive study. Ann. Ig. 2022; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Askarian, M.; Semenov, A.; Llopis, F.; Rubulotta, F.; Dragovac, G.; Pshenichnaya, N.; Assadian, O.; Ruch, Y.; Shayan, Z.; Padilla Fortunatti, C.; et al. The COVID-19 vaccination acceptance/hesitancy rate and its determinants among healthcare workers of 91 Countries: A multicenter cross-sectional study. EXCLI J. 2022, 21, 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Metwali, B.Z.; Al-Jumaili, A.A.; Al-Alag, Z.A.; Sorofman, B. Exploring the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers and general population using health belief model. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2021, 27, 1112–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, D.P.; Palter, J.S. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy among healthcare personnel in the emergency department deserves continued attention. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 48, 372–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubov, A.; Beeson, W.L.; Loo, L.K.; Montgomery, S.B.; Oyoyo, U.E.; Patel, P.; Peteet, B.; Shoptaw, S.; Tavakoli, S.; Chrissian, A.A.; et al. Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy among Healthcare Workers in Southern California: Not Just “Anti” vs. “Pro” Vaccine. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Ye, W.; Yu, J.; Gao, J.; Ren, Z.; Chen, L.; Dong, A.; Yi, Q.; Zhan, C.; Lin, Y.; et al. The landscape of COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare workers at the first round of COVID-19 vaccination in China: Willingness, acceptance and self-reported adverse effects. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 4846–4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, A.A.; Eisenbach, N.; Taiber, S.; Morozov, N.G.; Mizrachi, M.; Zigron, A.; Srouji, S.; Sela, E. Vaccine hesitancy: The next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 35, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, C.; Bénézit, F.; Geslin, M.; Polard, E.; Baldeyrou, M.; Turmel, V.; Tadié, E.; Garlantezec, R.; Tattevin, P. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers. Infect. Dis. Now 2021, 51, 484–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrichtova, R.; Svihrova, V.; Tatarkova, M.; Hudeckova, H.; Svihra, J. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination among Healthcare and Non-Healthcare Workers of Hospitals and Outpatient Clinics in the Northern Region of Slovakia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briko, N.I.; Korshunov, V.A.; Mindlina, A.Y.; Polibin, R.V.; Antipov, M.O.; Brazhnikov, A.I.; Vyazovichenko, Y.E.; Glushkova, E.V.; Lomonosov, K.S.; Lomonosova, A.V.; et al. Healthcare Workers’ Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination in Russia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Shekhnar, R.; Kottewar, S.; Upadhyay, S.; Singh, M.; Pathak, D.; Kapuria, D.; Barrett, E.; Sheikh, A.B. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Attitude toward Booster Doses among US Healthcare Workers. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qunaibi, E.; Basheti, I.; Soudy, M.; Sultan, I. Hesitancy of Arab Healthcare Workers towards COVID-19 Vaccination: A Large-Scale Multinational Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aperio Bella, F.; Lauri, C.; Capra, G. The Role of COVID-19 Soft Law Measures in Italy: Much Ado about Nothing? Eur. J. Risk Regul. 2021, 12, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morana, D. Emergency and regionalism in healthcare: Challenges for the Italian National Health Service during COVID-19 pandemic. Minerva Cardiol. Angiol. 2021, 69, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallina, P.; Ricci, M.; Lopez, P. COVID-19: Reading of the Italian response to the epidemic from a historical–literary point of view. Postgrad. Med. J. 2021, 97, 133–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, J. COVID-19: France and Greece make vaccination mandatory for healthcare workers. BMJ 2021, 373, n1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verger, P.; Scronias, D.; Dauby, N.; Adedzi, K.A.; Gobert, C.; Bergeat, M.; Gagneur, A.; Dubé, E. Attitudes of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 vaccination: A survey in France and French-speaking parts of Belgium and Canada, 2020. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2002047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grochowska, M.; Ratajczak, A.; Zdunek, G.; Adamiec, A.; Waszkiewcz, P.; Feleszko, W. A Comparison of the Level of Acceptance and Hesitancy towards the Influenza Vaccine and the Forthcoming COVID-19 Vaccine in the Medical Community. Vaccines 2021, 9, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, R.; Nguse, T.M.; Habte, B.M.; Fentie, A.M.; Gebretekle, G.B. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Ethiopian healthcare workers. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara Esen, B.; Can, G.; Pirdal, B.Z.; Aydin, S.N.; Ozdil, A.; Balkan, I.I.; Budak, B.; Keskindemirci, Y.; Karaali, R.; Saltoglu, N. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Healthcare Personnel: A University Hospital Experience. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lataifeh, L.; Al-Ani, A.; Lataifeh, I.; Ammar, K.; AlOmary, A.; Al-Hammouri, F.; Al-Hussaini, M. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Healthcare Workers in Jordan towards the COVID-19 Vaccination. Vaccines 2022, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhadi, M.; Alsoufi, A.; Alhadi, A.; Hmeida, A.; Alshareea, E.; Dokali, M.; Abodabos, S.; Alsadiq, O.; Abdelkabir, M.; Ashini, A.; et al. Knowledge, attitude, and acceptance of healthcare workers and the public regarding the COVID-19 vaccine: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, S.; Elmnyer, M.M.; Mohamed, S.S.; Elsayed, R. COVID-19 Vaccination Perception and Attitude among Healthcare Workers in Egypt. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2021, 12, 215013272110133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juyal, D.; Pal, S.; Negi, N.; Thaledi, S. Mandatory COVID-19 vaccination for healthcare workers: Need of the hour. World J. Nucl. Med. 2022, 21, 83–84. [Google Scholar]

- Galanakis, E.; Jansen, A.; Lopalco, P.L.; Giesecke, J. Ethics of mandatory vaccination for healthcare workers. Eurosurveillance 2013, 18, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kates, O.S.; Diekema, D.S.; Blumberg, E.A. Should Health Care Institutions Mandate SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination for Staff? Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, L.; Pollock, A.M. Mandatory covid-19 vaccination for care home workers. BMJ 2021, 374, n1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gur-Arie, R.; Jamrozik, E.; Kingori, P. No Jab, No Job? Ethical Issues in Mandatory COVID-19 Vaccination of Healthcare Personnel. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e004877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokol, D. COVID-19 vaccination should be mandatory for healthcare workers. BMJ 2021, 375, n2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinceti, S.R. COVID-19 Compulsory Vaccination of Healthcare Workers and the Italian Constitution. Ann. Ig. 2022, 34, 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Stokel-Walker, C. COVID-19: Why test and trace will fail without support for self-isolation. BMJ 2021, 372, n327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 449/2021. (VII. 29.) Korm. Rendelet a Koronavírus Elleni Védőoltás Kötelező Igénybevételéről. Available online: https://net.jogtar.hu/jogszabaly?docid=a2100449.kor (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Hμοκρατιασ, Τ.H.Σ.Ε.; Aριθμ, Ν.Υ.Π.; Θεσμοσ, Κ.A.O. Τησ κυβερνησεωσ. Available online: https://gr.euronews.com/2021/07/21/ellada-oles-oi-leptomeries-tis-rythmiseis-ypoxreotikoi-emvoliasmoi-covid-ti-isxyei-prostim (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Obligation to Vaccinate: Who Are the Public Officials Concerned? Available online: https://www.weka.fr/actualite/sante-et-securite-au-travail/article/obligation-de-vaccination-qui-sont-les-agents-publics-concernes-129515/ (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Saade, A.; Cha, L.; Tadié, E.; Jurado, B.; Le Bihan, A.; Baron-Latouche, P.; Febreau, C.; Thibault, V.; Garlantezec, R.; Tattevin, P. Delay between COVID-19 complete vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 infection among healthcare workers. Vaccine 2022, 40, 3159–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieszczenie, O.B.; Wia, M.I.Z. Warszawa, Dnia 10 Lutego 2022 r. Poz. 340. 2020–2023. 2022. Available online: https://www.infor.pl/akt-prawny/DZU.2022.041.0000340,rozporzadzenie-ministra-zdrowia-w-sprawie-ogloszenia-na-obszarze-rzeczypospolitej-polskiej-stanu-epidemii.html (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- European Parliamentary Research Service. Legal Issues Surrounding Compulsory COVID-19 Vaccination; European Parliamentary Research Service: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gesetzesbeschluss des Deutschen Bundestages. Gesetz Zur Stärkung Der Impfprävention Gegen COVID-19 UND Zur äNderung Weiterer Vorschriften Im Zusammenhang MIT Der Covid-19-Pandemie; volume 830/21 5162–5174; Deutschen Bundestages: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UK Vaccination Policy. Available online: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9076/ (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- The Decree on Compulsory Vaccination Was Published in the Collection of Laws, Covid Was Removed from It. Available online: https://advokatnidenik.cz/2022/02/02/ve-sbirce-zakonu-vysla-vyhlaska-o-povinnem-ockovani-covid-z-ni-byl-vyrazen/ (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Minister for Health. Public Health (COVID-19 Vaccination of Health Care Workers) Order (No 3) 2021; Public Health Act 2010; Minister for Health: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2021.

- COVID-19 Public Health Response (Vaccinations) Order 2021. Available online: https://www.legislation.govt.nz/regulation/public/2021/0094/latest/LMS487853.html (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Ntziora, F.; Kostaki, E.G.; Grigoropoulos, I.; Karapanou, A.; Kliani, I.; Mylona, M.; Thomollari, A.; Tsiodras, S.; Zaoutis, T.; Paraskevis, D.; et al. Vaccination Hesitancy among Health-Care-Workers in Academic Hospitals Is Associated with a 12-Fold Increase in the Risk of COVID-19 Infection: A Nine-Month Greek Cohort Study. Viruses 2021, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odone, A.; Bucci, D.; Croci, R.; Riccò, M.; Affanni, P.; Signorelli, C. Vaccine hesitancy in COVID-19 times. An update from Italy before flu season starts. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, e2020031. [Google Scholar]

- Fotiadis, K.; Dadouli, K.; Avakian, I.; Bogogiannidou, Z.; Mouchtouri, V.A.; Gogosis, K.; Speletas, M.; Koureas, M.; Lagoudaki, E.; Kokkini, S.; et al. Factors Associated with Healthcare Workers’ (HCWs) Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccinations and Indications of a Role Model towards Population Vaccinations from a Cross-Sectional Survey in Greece, May 2021. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltezou, H.C.; Pavli, A.; Dedoukou, X.; Georgakopoulou, T.; Raftopoulos, V.; Drositis, I.; Bolikas, E.; Ledda, C.; Adamis, G.; Spyrou, A.; et al. Determinants of intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19 among healthcare personnel in hospitals in Greece. Infect. Dis. Health 2021, 26, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moirangthem, S.; Olivier, C.; Gagneux-Brunon, A.; Péllissier, G.; Abiteboul, D.; Bonmarin, I.; Rouveix, E.; Botelho-Nevers, E.; Mueller, J.E. Social conformism and confidence in systems as additional psychological antecedents of vaccination: A survey to explain intention for COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare and welfare sector workers, France, December 2020 to February 2021. Euro Surveill. 2022, 27, 2100617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakonti, G.; Kyprianidou, M.; Toumbis, G.; Giannakou, K. Attitudes and Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination Among Nurses and Midwives in Cyprus: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 656138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, C.S.; Mujeeb, A.A.; Mirza, M.S.; Chaudhry, B.; Khan, S.J. Global COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance: A Systematic Review of Associated Social and Behavioral Factors. Vaccines 2022, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, K.O.; Li, K.; Wei, W.I.; Tang, A.; Wong, S.Y.S.; Lee, S.S. Influenza vaccine uptake, COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine hesitancy among nurses: A survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 114, 103854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, R.; Sheikh, A.B.; Upadhyay, S.; Singh, M.; Kottewar, S.; Mir, H.; Barrett, E.; Pal, S. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Health Care Workers in the United States. Vaccines 2021, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannis, D.; Rachiotis, G.; Malli, F.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Kotsiou, O.; Fradelos, E.C.; Giannakopoulos, K.; Gourgoulianis, K.I. Acceptability of COVID-19 Vaccination among Greek Health Professionals. Vaccines 2021, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledda, C.; Costantino, C.; Cuccia, M.; Maltezou, H.C.; Rapisarda, V. Attitudes of Healthcare Personnel towards Vaccinations before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, F.; Murri, R.; Segala, F.V.; Cerruti, L.; Abdulle, A.; Saracino, A.; Bavaro, D.F.; Fantoni, M. Attitudes towards Anti-SARS-CoV2 Vaccination among Healthcare Workers: Results from a National Survey in Italy. Viruses 2021, 13, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, C.; Maillard, A.; Bodelet, C.; Claudel, A.; Gaillat, J.; Delory, T. Hesitancy towards COVID-19 Vaccination among Healthcare Workers: A Multi-Centric Survey in France. Vaccines 2021, 9, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboa, M.; Tal, I.; Levin, E.G.; Segal, S.; Belkin, A.; Zilberman-Daniels, T.; Biber, A.; Rubin, C.; Rahav, G.; Regev-Yochay, G. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination uptake among healthcare workers. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2021, 2019, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, N.; Mustapha, T.; Khubchandani, J.; Price, J.H. The Nature and Extent of COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in Healthcare Workers. J. Community Health 2021, 46, 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lou, Y.; Watson, R.; Zheng, Y.; Ren, J.; Tang, J.; Chen, Y. Healthcare workers’ (HCWs) attitudes and related factors towards COVID-19 vaccination: A rapid systematic review. Postgrad. Med. J. 2021, 140195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuown, A.; Ellis, T.; Miller, J.; Davidson, R.; Kachwala, Q.; Medeiros, M.; Mejia, K.; Manoraj, S.; Sidhu, M.; Whittington, A.M.; et al. COVID-19 vaccination intent among London healthcare workers. Occup. Med. 2021, 71, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzmann-Littig, C.; Braunisch, M.; Kranke, P.; Popp, M.; Seeber, C.; Fichtner, F.; Littig, B.; Carbajo-Lozoya, J.; Allwang, C.; Frank, T.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Acceptance and Hesitancy among Healthcare Workers in Germany. Vaccines 2021, 9, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arghittu, A.; Dettori, M.; Dempsey, E.; Deiana, G.; Angelini, C.; Bechini, A.; Bertoni, C.; Boccalini, S.; Bonanni, P.; Cinquetti, S.; et al. Health Communication in COVID-19 Era: Experiences from the Italian VaccinarSì Network Websites. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schernhammer, E.; Weitzer, J.; Laubichler, M.D.; Birmann, B.M.; Bertau, M.; Zenk, L.; Caniglia, G.; Jäger, C.C.; Steiner, G. Correlates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Austria: Trust and the government. J. Public Health 2022, 44, e106–e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwell, K.; Harper, T.; Rizzi, M.; Taylor, J.; Casigliani, V.; Quattrone, F.; Lopalco, P. Inaction, under-reaction action and incapacity: Communication breakdown in Italy’s vaccination governance. Policy Sci. 2021, 54, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Total Sample (n = 130) | Healthcare Workers/Profession | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians (n = 38) | Nurses (n = 58) | Other HCWs (n = 34) | p-Value | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Age | 0.192 | ||||||||

| </= 30 | 24 | 18.5% | 4 | 10.5% | 11 | 19.0% | 9 | 26.5% | |

| 31–40 | 29 | 22.3% | 12 | 31.6% | 12 | 20.7% | 5 | 14.7% | |

| 41–50 | 34 | 26.2% | 12 | 31.6% | 14 | 24.1% | 8 | 23.5% | |

| 51–60 | 39 | 30.0% | 8 | 21.1% | 21 | 36.2% | 10 | 29.4% | |

| >60 | 4 | 3.1% | 2 | 5.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 5.9% | |

| Sex | 0.007 | ||||||||

| Male | 33 | 25.4% | 17 | 44.7% | 10 | 17.2% | 6 | 17.6% | |

| Female | 97 | 74.6% | 21 | 55.3% | 48 | 82.8% | 28 | 82.4% | |

| Does your profession put you in direct contact with patients? | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 96 | 73.8% | 34 | 89.5% | 48 | 82.8% | 14 | 41.2% | |

| No | 34 | 26.2% | 4 | 10.5% | 10 | 17.2% | 20 | 58.8% | |

| Have you worked in units with COVID-19 patients since the beginning of the COVID-19 emergency? | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 75 | 57.7% | 28 | 73.7% | 37 | 63.8% | 10 | 29.4% | |

| No | 55 | 42.3% | 10 | 26.3% | 21 | 36.2% | 24 | 70.6% | |

| Do you have a disease that prevented you from receiving the vaccine? (NB: This question takes into consideration one or more known conditions that have caused either your general practitioner OR the doctor present at the vaccination hub to deny you the possibility of being vaccinated) | na | ||||||||

| Yes | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| No | 130 | 100.0% | 38 | 100.0% | 58 | 100.0% | 34 | 100.0% | |

| Characteristic | Total Sample (n = 130) | Healthcare Workers/Profession | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians (n = 38) | Nurses (n = 58) | Other HCWs (n = 34) | p-Value | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Have you tested positive for COVID-19 in the past? | 0.634 | ||||||||

| Yes | 46 | 35.4% | 11 | 28.9% | 22 | 37.9% | 13 | 38.2% | |

| No | 84 | 64.6% | 27 | 71.1% | 36 | 62.1% | 21 | 61.8% | |

| Are you currently positive for COVID-19? | na | ||||||||

| Yes | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| No | 130 | 100.0% | 38 | 100.0% | 58 | 100.0% | 34 | 100.0% | |

| If you have tested/are currently positive for COVID-19, have you had/are you suffering from a form of infection that is: | 0.438 | ||||||||

| Asymptomatic | 6 | 4.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 8.6% | 1 | 2.9% | |

| Mild symptomatic (common symptomatology of COVID-19 infection without the need for hospitalization) | 31 | 23.8% | 7 | 18.4% | 13 | 22.4% | 11 | 32.4% | |

| Severe symptoms (symptoms linked to COVID-19 infection with the need for assistance/hospitalization) | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Symptomatic with sequelae | 1 | 0.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.7% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Are there people among your acquaintances (relatives and close friends) who tested/are currently positive for the COVID-19 test? | 1.000 | ||||||||

| Yes | 117 | 90.0% | 35 | 92.1% | 52 | 89.7% | 30 | 88.2% | |

| No | 12 | 9.2% | 3 | 7.9% | 6 | 10.3% | 3 | 8.8% | |

| Are there people among your acquaintances (relatives and close friends) who died from COVID-19 infection? | 0.498 | ||||||||

| Yes | 30 | 23.1% | 11 | 28.9% | 11 | 19.0% | 8 | 23.5% | |

| No | 100 | 76.9% | 27 | 71.1% | 47 | 81.0% | 26 | 76.5% | |

| Characteristic | Total Sample (n = 130) | Healthcare Workers/Profession | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians (n = 38) | Nurses (n = 58) | Other HCWs (n = 34) | p-Value | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

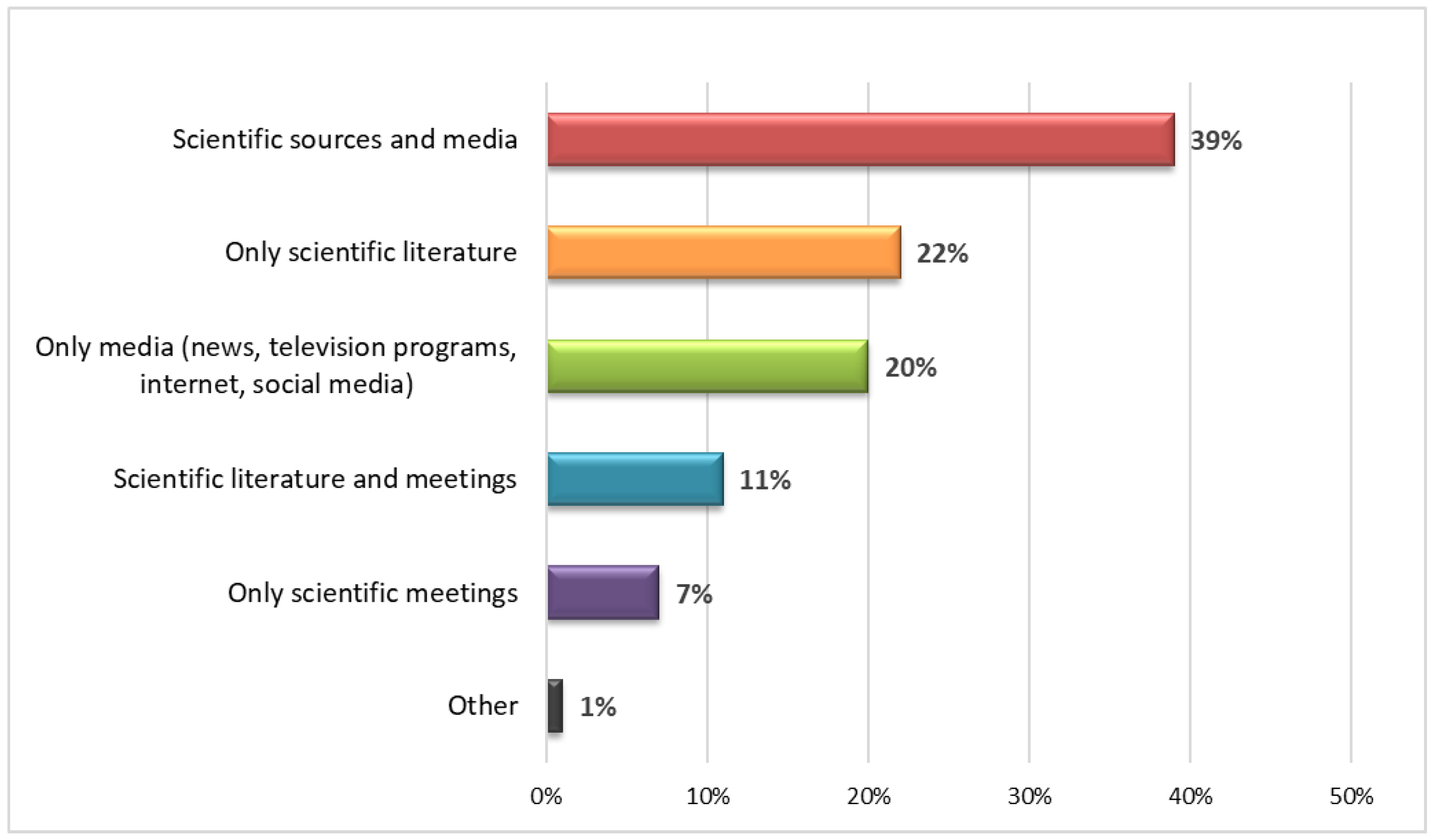

| What is your main source of information on the COVID-19 pandemic? | 0.044 | ||||||||

| Only scientific literature | 28 | 21.5% | 11 | 28.9% | 8 | 13.8% | 9 | 26.5% | |

| Only scientific meetings | 9 | 6.9% | 2 | 5.3% | 7 | 12.1% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Scientific literature and meetings | 14 | 10.8% | 6 | 15.8% | 5 | 8.6% | 3 | 8.8% | |

| Only media (news/television programs)/Internet and social media | 26 | 20.0% | 4 | 10.5% | 14 | 24.1% | 8 | 23.5% | |

| Scientific sources and media | 51 | 39.2% | 15 | 39.5% | 23 | 39.7% | 13 | 38.2% | |

| Other | 2 | 1.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.7% | 1 | 2.9% | |

| Do you think the number of cases and deaths has been overestimated? | 0.050 | ||||||||

| Yes | 39 | 30.0% | 6 | 15.8% | 19 | 32.8% | 14 | 41.2% | |

| No | 91 | 70.0% | 32 | 84.2% | 39 | 67.2% | 20 | 58.8% | |

| Do you think that the complications derived from COVID-19 infection can have a serious impact on people’s health? | 0.642 | ||||||||

| Yes | 116 | 89.2% | 35 | 92.1% | 52 | 89.7% | 29 | 85.3% | |

| No | 14 | 10.8% | 3 | 7.9% | 6 | 10.3% | 5 | 14.7% | |

| In your opinion, for the entire population, without delving into a specific area (health, economy, etc.), how serious is COVID-19 on a scale from 1 to 10? | 0.430 | ||||||||

| Not severe (0–4) | 7 | 5.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 8.6% | 2 | 5.9% | |

| Moderately severe (5–6) | 44 | 33.8% | 13 | 34.2% | 18 | 31.0% | 13 | 38.2% | |

| Very severe (7–10) | 79 | 60.8% | 25 | 65.8% | 35 | 60.3% | 19 | 55.9% | |

| Characteristic | Total Sample (n = 130) | Healthcare Workers/Profession | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians (n = 38) | Nurses (n = 58) | Other HCWs (n = 34) | p-Value | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Do you receive the flu vaccination annually? | 0.003 | ||||||||

| Yes | 69 | 53.1% | 29 | 76.3% | 25 | 43.1% | 15 | 44.1% | |

| No | 61 | 46.9% | 9 | 23.7% | 33 | 56.9% | 19 | 55.9% | |

| Do you advise your patients to receive the recommended vaccinations (e.g., anti-flu at > 60 years)? | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Always | 55 | 42.3% | 26 | 68.4% | 23 | 39.7% | 6 | 17.6% | |

| Sometimes | 22 | 16.9% | 3 | 7.9% | 13 | 22.4% | 6 | 17.6% | |

| Never | 5 | 3.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 8.6% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| It is not part of my professional duties | 48 | 36.9% | 9 | 23.7% | 17 | 29.3% | 22 | 64.7% | |

| Do you believe in science for the development of new, safe, and effective vaccines? | 0.615 | ||||||||

| Yes | 127 | 97.7% | 38 | 100.0% | 56 | 96.6% | 33 | 97.1% | |

| No | 3 | 2.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 3.4% | 1 | 2.9% | |

| Do you believe that the safety of a vaccine developed during an emergency can be guaranteed? | 0.008 | ||||||||

| Yes | 108 | 83.1% | 37 | 97.4% | 44 | 75.9% | 27 | 79.4% | |

| No | 22 | 16.9% | 1 | 2.6% | 14 | 24.1% | 7 | 20.6% | |

| Do you believe that the vaccine against the COVID-19 virus will be useful for the control of the disease? | 0.027 | ||||||||

| Yes | 120 | 92.3% | 38 | 100% | 50 | 86.2% | 32 | 94.1% | |

| No | 10 | 7.7% | 0 | / | 8 | 13.8% | 2 | 5.9% | |

| Are you concerned about the serious complications of the COVID-19 vaccine? | 0.051 | ||||||||

| Yes, I’m seriously worried | 9 | 6.9% | 1 | 2.6% | 7 | 12.1% | 1 | 2.9% | |

| Yes, I’m worried | 35 | 26.9% | 6 | 15.8% | 17 | 29.3% | 12 | 35.3% | |

| No, I’m not worried | 75 | 57.7% | 24 | 63.2% | 32 | 55.2% | 19 | 55.9% | |

| No, I’m not worried at all | 11 | 8.5% | 7 | 18.4% | 2 | 3.4% | 2 | 5.9% | |

| Do you think that the mandatory vaccination of healthcare workers is right? | 0.004 | ||||||||

| Yes | 107 | 82.3% | 37 | 97.4% | 42 | 72.4% | 28 | 82.4% | |

| No | 23 | 17.7% | 1 | 2.6% | 16 | 27.6% | 6 | 17.6% | |

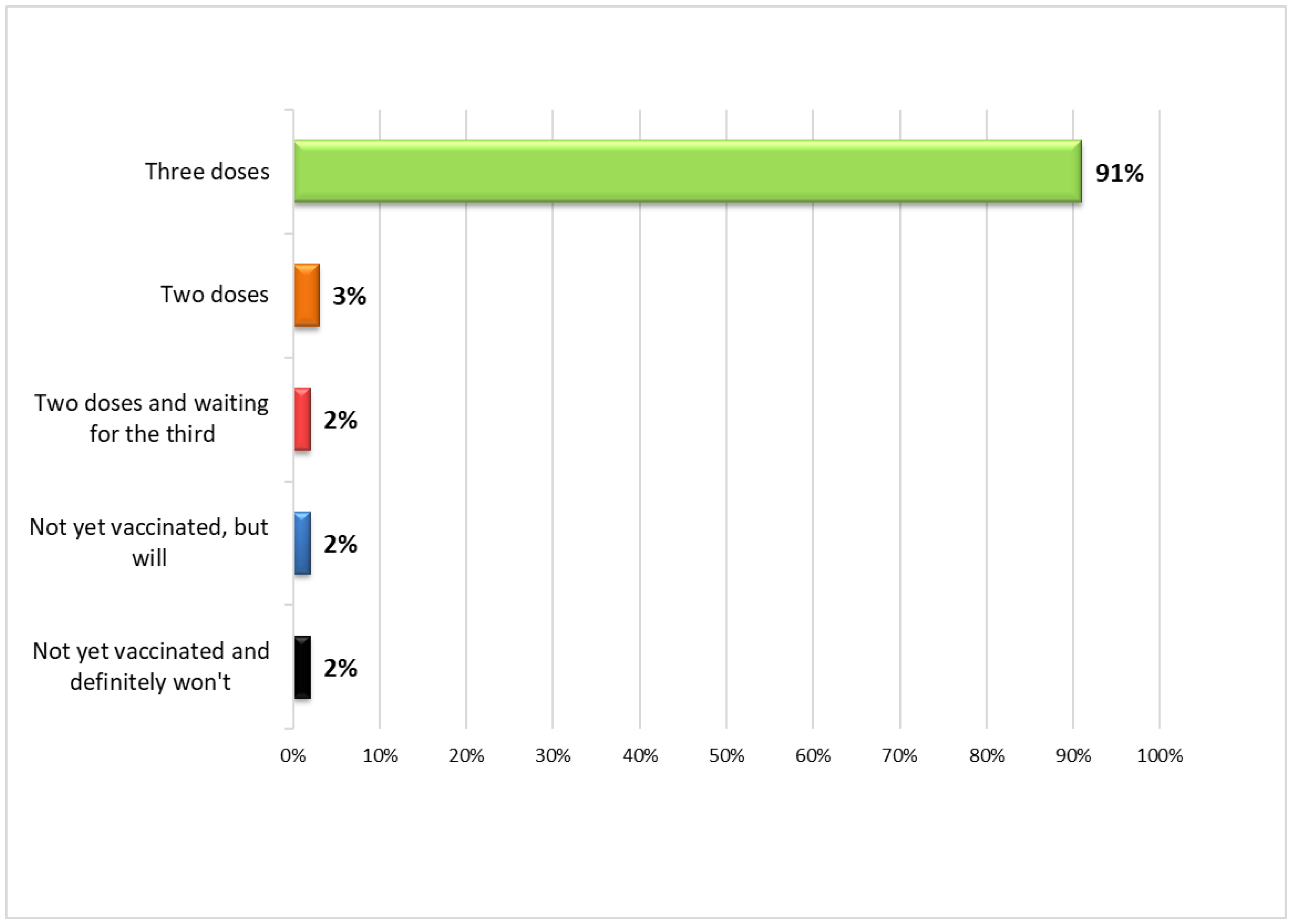

| Did you received the COVID-19 vaccine? | 0.623 | ||||||||

| Yes, I received two doses and the booster dose (third dose) | 119 | 91.5% | 38 | 100.0% | 51 | 87.9% | 30 | 88.2% | |

| Yes, I’m waiting for the third dose | 2 | 1.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.7% | 1 | 2.9% | |

| Yes, I received both doses | 4 | 3.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 3.4% | 2 | 5.9% | |

| No, but I definitely will | 2 | 1.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 3.4% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| No, and I definitely won’t | 3 | 2.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 3.4% | 1 | 2.9% | |

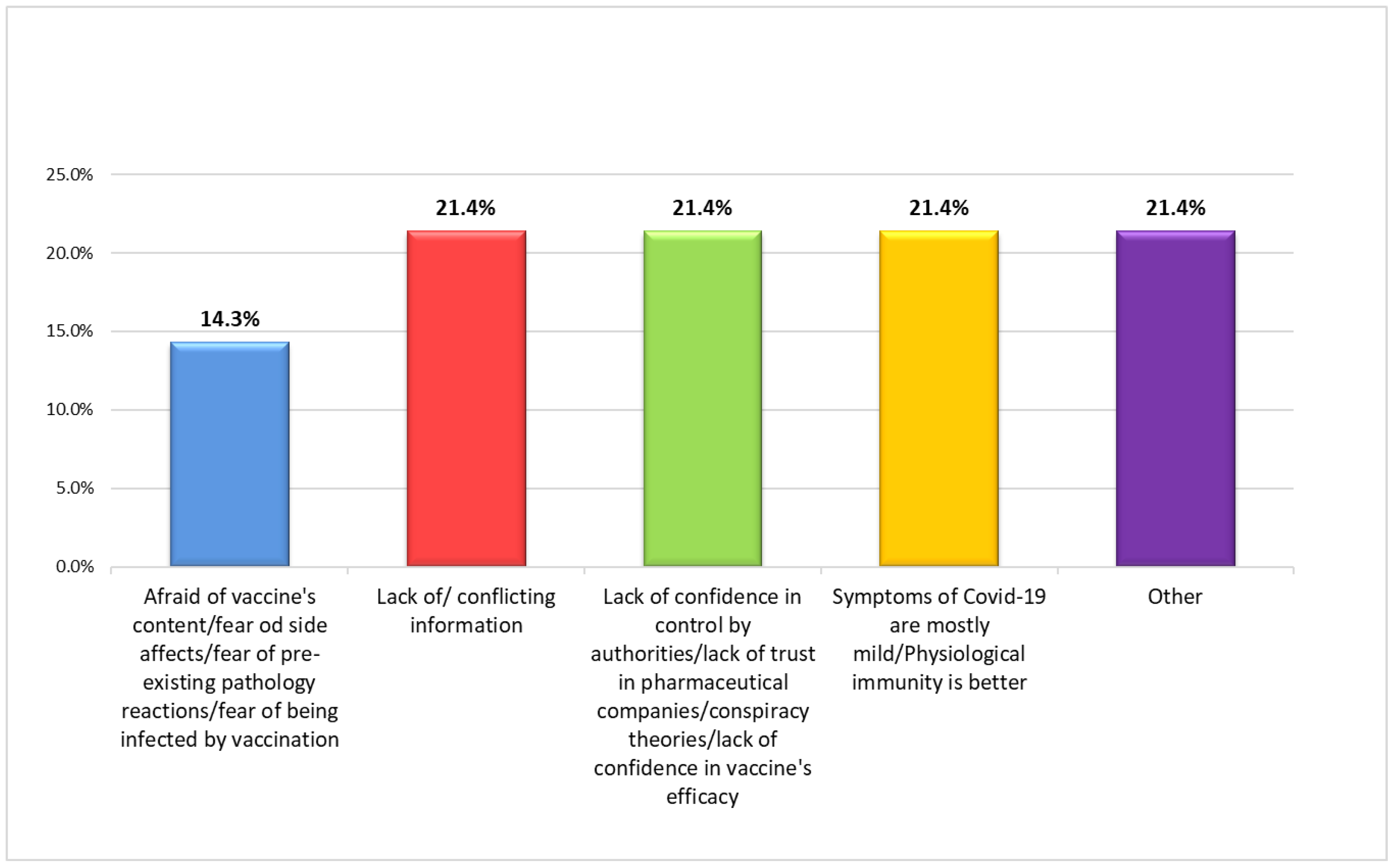

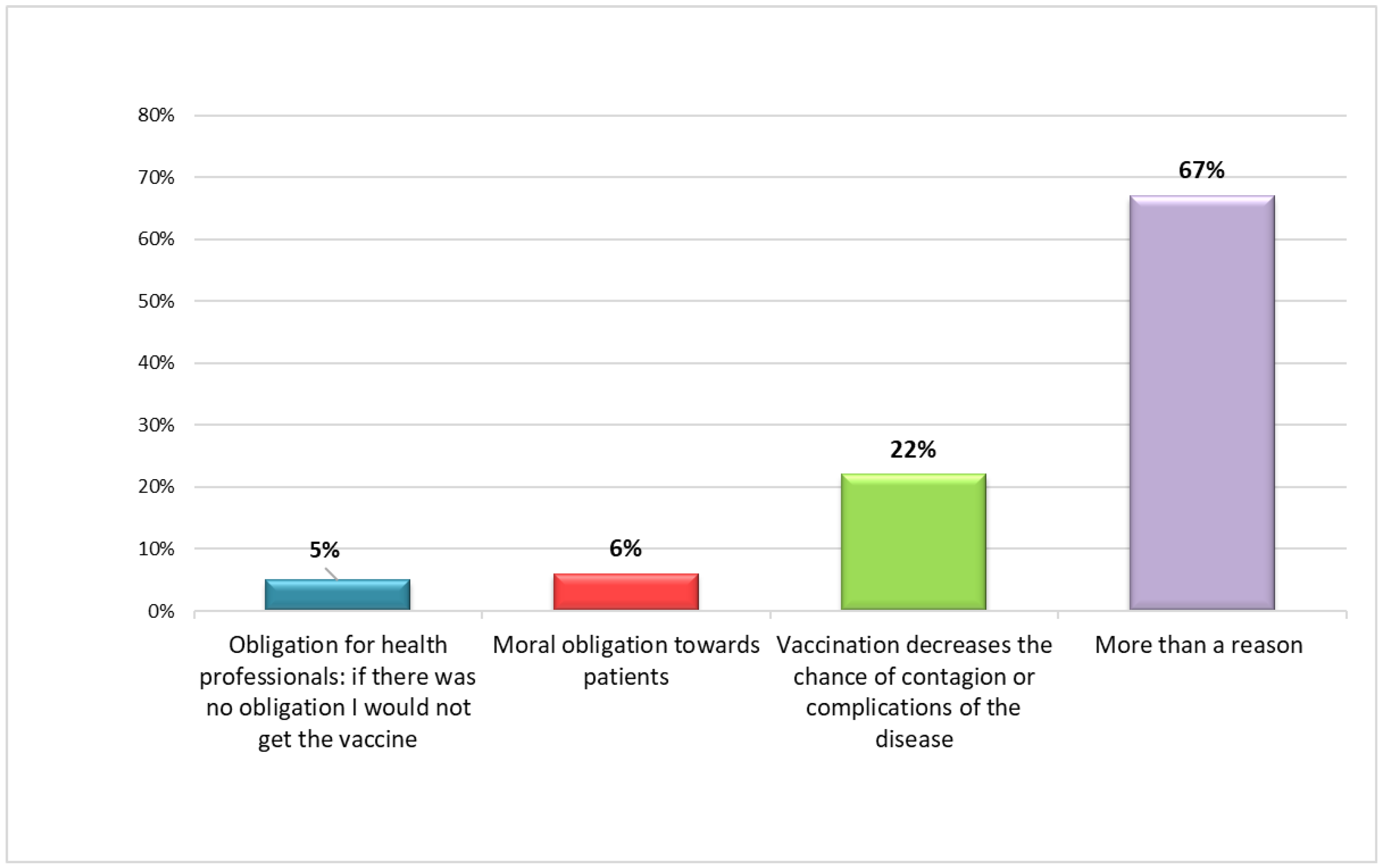

| If you have been vaccinated or are planning to be vaccinated, what are the reasons for your choice? | 0.064 | ||||||||

| To have access to activities and services that would otherwise be precluded in the absence of Green Certification/Greenpass (bars, restaurants, cinemas, etc.) | 0 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | ||||

| Obligatory vaccine for health professionals; if there was no obligation, I would not have vaccinated myself/I would not be vaccinated | 6 | 4.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 9.6% | 1 | 23.3% | |

| Vaccination decreases the chances of contagion or complications of the disease | 27 | 21.9% | 13 | 34.2% | 9 | 17.3% | 5 | 15.1% | |

| Moral obligation towards patients | 7 | 5.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 7.7% | 3 | 9.1% | |

| More than one option | 83 | 67.5% | 25 | 65.8% | 34 | 65.4% | 24 | 72.7% | |

| Do you recommend/have you recommended/will you advise your acquaintances (relatives and close friends) to be vaccinated against COVID-19? | 0.023 | ||||||||

| Yes | 118 | 90.8% | 38 | 100.0% | 49 | 84.5% | 31 | 91.2% | |

| No | 12 | 9.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 15.5% | 3 | 8.8% | |

| Country | Legal Reference | Come into Force | Professional Figures with Mandatory Vaccination | Population-Wide Mandatory Vaccination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | Law 2021/1040, Articles 12–13 | 15 September 2021 | HCWs, health professions students, fire, civil protection workers. | No |

| Germany | Infection Protection Act, Article 20a | 15 March 2022 | HCWs | No |

| Greece | Law 4829/2021, Article 206 | 12 July 2021 | HCWs, firefighters. | Residents over 60 (Article 24, Law 4865/2021) |

| Hungary | Government Decree 449/2921 (VII.29.) | 15 September 2021 | Healthcare Education, cultural institutions, army (Government Decree 599/2921 (X.28.)) | No |

| Italy | Decree Law N. 44/2021 | 1 April 2021 | HCWs, police, education, social care | Residents over 50 (Decree-Law 1/2022) |

| Latvia | Amendments to the COVID-19 Infection Control Law | 1 October 2021 | Workers in private and public sectors (healthcare, education, etc.) | No |

| Poland | Dz. U. z 2022 r. poz. 340 | 1 March 2022 | HCWs | No |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peruch, M.; Toscani, P.; Grassi, N.; Zamagni, G.; Monasta, L.; Radaelli, D.; Livieri, T.; Manfredi, A.; D’Errico, S. Did Italy Really Need Compulsory Vaccination against COVID-19 for Healthcare Workers? Results of a Survey in a Centre for Maternal and Child Health. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081293

Peruch M, Toscani P, Grassi N, Zamagni G, Monasta L, Radaelli D, Livieri T, Manfredi A, D’Errico S. Did Italy Really Need Compulsory Vaccination against COVID-19 for Healthcare Workers? Results of a Survey in a Centre for Maternal and Child Health. Vaccines. 2022; 10(8):1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081293

Chicago/Turabian StylePeruch, Michela, Paola Toscani, Nicoletta Grassi, Giulia Zamagni, Lorenzo Monasta, Davide Radaelli, Tommaso Livieri, Alessandro Manfredi, and Stefano D’Errico. 2022. "Did Italy Really Need Compulsory Vaccination against COVID-19 for Healthcare Workers? Results of a Survey in a Centre for Maternal and Child Health" Vaccines 10, no. 8: 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081293

APA StylePeruch, M., Toscani, P., Grassi, N., Zamagni, G., Monasta, L., Radaelli, D., Livieri, T., Manfredi, A., & D’Errico, S. (2022). Did Italy Really Need Compulsory Vaccination against COVID-19 for Healthcare Workers? Results of a Survey in a Centre for Maternal and Child Health. Vaccines, 10(8), 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081293