Informed Consent in Mass Vaccination against COVID-19 in Romania: Implications of Bad Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Romanian Legal Framework Regarding Patient’s Informed Consent

2.1. How Informed the Informed Consent Should Be?

2.2. Informed Consent—A Signature on a Legal Document

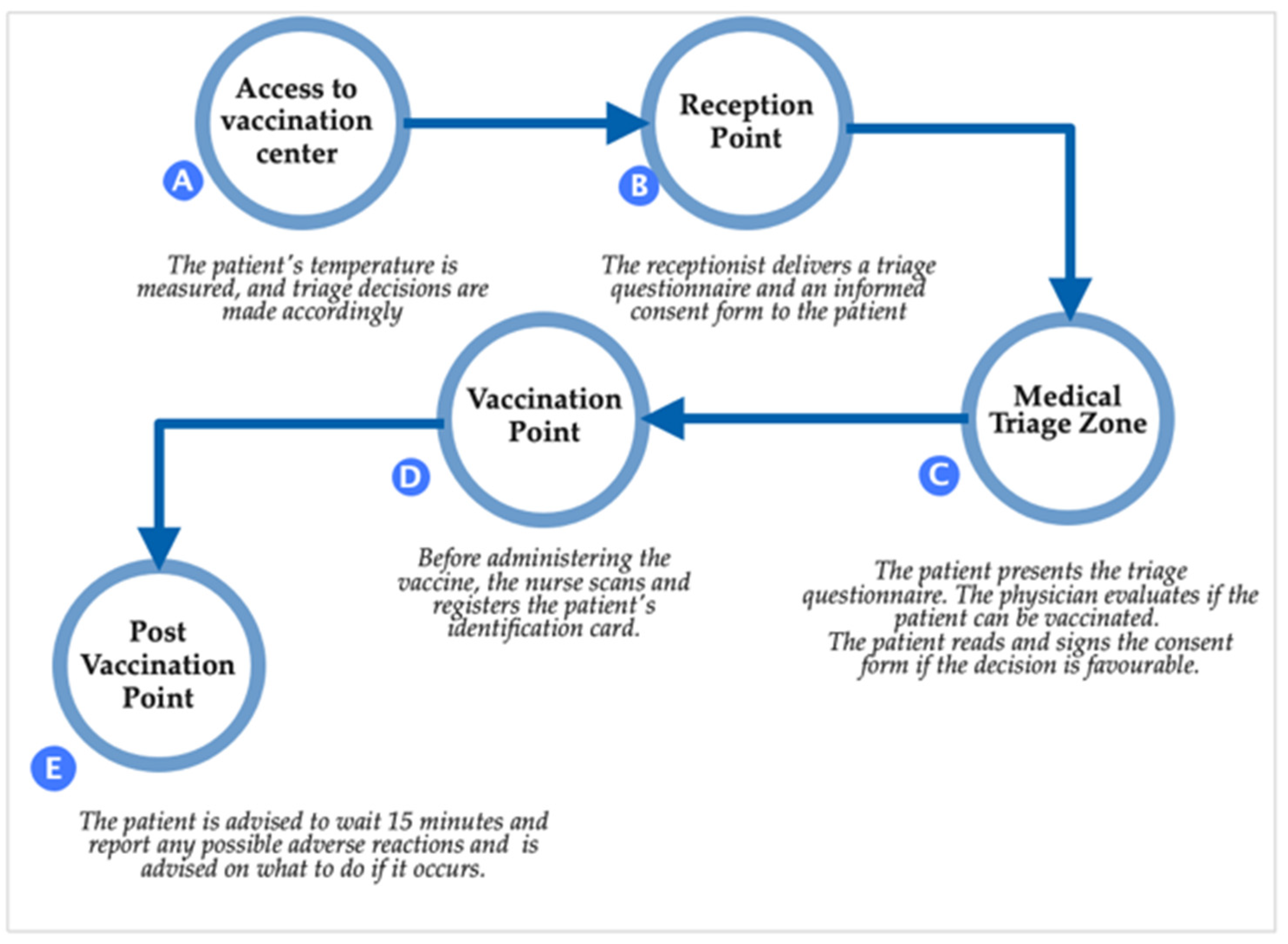

3. Assessing Legal Validity of the Patient’s Informed Consent Used during the Romanian Vaccination Campaign

- Information related to the patient’s personal data;

- A pre-filled brief description of the medical act (vaccination);

- An acknowledgment statement.

- There was no law, order, or other regulation issuing this document. We searched the legal database accessible through legislation software (Indaco Lege5 and Sintact) and Google. Nevertheless, we could not identify any official act adopting this informed consent form used during the vaccination campaign. Therefore, we consider that the vaccination informed consent form made available on the vaccination web platform did not have legal grounds.

- According to the hierarchic system of laws general principle [27] and Romanian law no. 24/2000, any amendment of a normative act in force is permitted only by an act of higher or equal rank. Consequently, at least a Ministry Order was required for the new informed consent to be legitimate. There is one official document related to the vaccination campaign strategy, Health Ministry Order no. 2171/2020, for establishing norms regarding the authorization, organization, and operation of vaccination centers against COVID-19. This order does not mention any derogation regarding the patient’s informed consent, but it simply states the necessity for the patient to sign an informed consent form.

- The National Committee for Coordination of Activities Regarding Vaccination Against COVID-19 was not legally authorized to amend law no. 95/2006 on health reform and order no. 1411/2016 of the Ministry of Health and, therefore, to alter the informed consent form.

4. Legal Implications of Deficient Informed Consent during the COVID-19 Vaccination Campaign

5. Other Implications

5.1. Medical Malpractice Insurance Agreements

5.2. Low Vaccination Rate

6. Proposed Changes to the Vaccination Campaign

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Europe TPAotCo. COVID-19 vaccines: Ethical, Legal and Practical Considerations. 2021. 2361. Available online: https://pace.coe.int/en/files/29004/html (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Paterlini, M. COVID-19: Italy makes vaccination mandatory for healthcare workers. BMJ 2021, 373, n905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, J. COVID-19: Is the UK heading towards mandatory vaccination of healthcare workers? BMJ 2021, 373, n1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokel-Walker, C. COVID-19: The countries that have mandatory vaccination for health workers. BMJ 2021, 373, n1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, K.O.; Lai, F.; Wei, W.I.; Wong, S.Y.S.; Tang, J.W.T. Herd immunity—Estimating the level required to halt the COVID-19 epidemics in affected countries. J. Infect. 2020, 80, e32–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicher, M.; Rippinger, C.; Schneckenreither, G.; Weibrecht, N.; Urach, C.; Zechmeister, M.; Brunmeir, D.; Huf, W.; Popper, N. Model based estimation of the SARS-CoV-2 immunization level in austria and consequences for herd immunity effects. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbari, A. COVID-19 Vaccine Concerns: Fact or Fiction? Exp. Clin. Transplant. 2021, 19, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Garcia, M.; Szech, N. Incentives and Defaults Can Increase COVID-19 Vaccine Intentions and Test Demand. Manag. Sci. 2022; ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Betsch, C.; Böhm, R.; Korn, L.; Holtmann, C. On the benefits of explaining herd immunity in vaccine advocacy. Nature Human Behaviour. 2017, 1, 0056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannovo, N.; Scendoni, R.; Fede, M.M.; Siotto, F.; Fedeli, P.; Cingolani, M. Nursing Home and Vaccination Consent: The Italian Perspective. Vaccines 2021, 9, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferorelli, D.; Mandarelli, G.; Solarino, B. Ethical Challenges in Health Care Policy during COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy. Medicina 2020, 56, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurwitz, D. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Lessons from Israel. Vaccine 2021, 39, 3785–3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platforma Națională de Informare cu Privire la Vaccinarea Împotriva COVID-19. Available online: https://vaccinare-covid.gov.ro/ (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Dascalu, S.; Geambasu, O.; Covaciu, O.; Chereches, R.M.; Diaconu, G.; Dumitra, G.G.; Gheorghita, V.; Popovici, E.D. Prospects of COVID-19 Vaccination in Romania: Challenges and Potential Solutions. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 644538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formulare și Chestionare. Available online: https://vaccinare-covid.gov.ro/formulare-si-chestionare/ (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Form, C.-V.C. Available online: https://www.gov.mb.ca/asset_library/en/covid/covid19_consent_form.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- CONSENSO VA-C-MD. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pagineAree_5452_5_file.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- ANTI-COVID-19 AAMDCV. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pagineAree_5452_5_file.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- COVID-19 vaccination: Consent form and letter for adults. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-vaccination-consent-form-and-letter-for-adults. (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Cocanour, C.S. Informed consent—It’s more than a signature on a piece of paper. Am. J. Surg. 2017, 214, 993–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feld, A.D. Informed consent: Not just for procedures anymore. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 99, 977–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- English, D.C. Valid informed consent: A process, not a signature. Am. Surg. 2002, 68, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, S. Legal and Ethical Issues for Mental Health Clinicians: Best Practices For Avoiding Litigation, Complaints and Malpractice; PESI Publishing & Media: Eau Claire, WI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Decision no. 834. 2011. Available online: https://asociatiaprovita.ro/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/docsjustDrOprea-Provita-Down.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Singeorzan, D. Pre-contractual Information of the Patient. Acta Univ. Lucian Blaga 2018, 180. [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 CNdCaApVi. Procedura de lucru pentru vaccinare in functie de tipul vaccinului. 2020. Available online: https://www.spsnm.ro/public/data_files/content-static/vaccinare-covid-19/proceduri-vaccinare/procedura-de-lucru-pentru-vaccinare-in-functie-de-tipul-vaccinului.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Kelsen, H.; Trevino, A.J. General Theory of Law & State; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- López, J.I.A. Vaccines, informed consent, effective remedy and integral reparation: An international human rights perspective. Vniversitas 2016, 131, 19–63. [Google Scholar]

- Vaccination Iaddpdscpl. Available online: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdfvaccination_covid_affiches_ehpad_usld.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Guide C-vCI. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-26-covid-19-vaccine.html (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Amantea, C.; Rossi, M.F.; Santoro, P.E.; Beccia, F.; Gualano, M.R.; Borrelli, I.; da Costa, J.P.; Daniele, A.; Tumminello, A.; Boccia, S.; et al. Medical Liability of the Vaccinating Doctor: Comparing Policies in European Union Countries during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, W.K.G.; Keulers, B.J.; Scheltinga, M.R.M.; Spauwen, P.H.M.; van der Wilt, G.-J. A Review of Surgical Informed Consent: Past, Present, and Future. A Quest to Help Patients Make Better Decisions. World J. Surg. 2010, 34, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seely, K.D.; Higgs, J.A.; Nigh, A. Utilizing the “teach-back” method to improve surgical informed consent and shared decision-making: A review. Patient Saf. Surg. 2022, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentinta civila numarul 11508/2014. Judecatoria Bucuresti Sectorul 4. 2014.

- Ollat, D. Preoperative information: Written first? Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2021, 107, 102771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuglay, I. Raspunderea Penala Pentru Malpraxis Medical; C.H. Beck: Bucharest, Romania, 2021; 344p. [Google Scholar]

- Bolcato, M.; Shander, A.; Isbister, J.P.; Trentino, K.M.; Russo, M.; Rodriguez, D.; Aprile, A. Physician autonomy and patient rights: Lessons from an enforced blood transfusion and the role of patient blood management. Vox Sang. 2021, 116, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Călin, R.M. Malpraxis: Răspunderea Personalului Medical şi a Furnizorului de Servicii Medicale: Practică Judiciară; Editura Hamangiu: Bucharest, Romania, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hotărârea, nr. Hotărârea nr. 11163 Judecatoria Craiova. 2013. Available online: https://www.curieruljudiciar.ro/2015/02/25/malpraxis-neindeplinirea-conditiilor-raspunderii-civile-delictuale-culpa-medicala/ (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Decizia penală nr. 200 Curtea de Apel Bucuresti. 2010.

- ICCJ. Decizia civila 2658. 2014. Available online: http://www.scj.ro/1093/Detalii-jurisprudenta?customQuery%5B0%5D.Key=id&customQuery%5B0%5D.Value=114083 (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- 2022 Corw. Available online: https://covid19-country-overviews.ecdc.europa.eu/ (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Steinert, J.I.; Sternberg, H.; Prince, H.; Fasolo, B.; Galizzi, M.M.; Büthe, T.; Veltri, G.A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in eight European countries: Prevalence, determinants, and heterogeneity. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm9825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razai, M.S.; Chaudhry, U.A.R.; Doerholt, K.; Bauld, L.; Majeed, A. Covid-19 vaccination hesitancy. BMJ 2021, 373, n1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhama, K.; Sharun, K.; Tiwari, R.; Dhawan, M.; Emran, T.B.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alhumaid, S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy—Reasons and solutions to achieve a successful global vaccination campaign to tackle the ongoing pandemic. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 3495–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieselmann, J.; Annac, K.; Erdsiek, F.; Yilmaz-Aslan, Y.; Brzoska, P. What are the reasons for refusing a COVID-19 vaccine? A qualitative analysis of social media in Germany. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Chen, L.; Pan, Q.N.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Yi, J.J.; Chen, C.M.; Luo, Q.H.; Tao, P.Y.; Pan, X.; et al. Vaccination status, acceptance, and knowledge toward a COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers: A cross-sectional survey in China. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 4065–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Wyka, K.; White, T.M.; Picchio, C.A.; Rabin, K.; Ratzan, S.C.; Parsons Leigh, J.; Hu, J.; El-Mohandes, A. Revisiting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy around the world using data from 23 countries in 2021. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardosh, K.; de Figueiredo, A.; Gur-Arie, R.; Jamrozik, E.; Doidge, J.; Lemmens, T..; Keshavjee, S.; Graham, J.; Baral, S. The unintended consequences of COVID-19 vaccine policy: Why mandates, passports and restrictions may cause more harm than good. BMJ Global Health 2022, 7, e008684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Shi, L.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Jiao, J.; Liu, M.; Yang, J.; Sun, G. Comparison of COVID-19 Vaccine Policies in Italy, India, and South Africa. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, T.; Schmidt-Petri, C.; Schröder, C. Attitudes Toward Mandatory COVID-19 Vaccination in Germany. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2022, 119, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprengholz, P.; Betsch, C.; Böhm, R. Reactance revisited: Consequences of mandatory and scarce vaccination in the case of COVID-19. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2021, 13, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumelty, M.-E.; Donnelly, M.; Farrell, A.-M.; Ó Néill, C. COVID-19 Vaccination and Legal Preparedness: Lessons from Ireland. Eur. J. Health Law 2022, 29, 240–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mandatory Legal Elements | Legal Reference |

|---|---|

| 1. Information regarding certain aspects related to the medical act: | article 660, Law no. 95/2006 and article 6, Law no. 46/2003 |

| |

| 2. The identity and professional status of health service providers3. Rules and customs that must be respected by patients during hospitalization | article 5, Law no. 46/2003 |

| 4. Available medical services and how to use them | article 4, Law no. 46/2003 |

| 5. Patient’s consent is mandatory for the collection, storage, use of all biological products taken from his/her body, in order to establish the diagnosis or the treatment with which he/she agrees. | article 18, Law no. 46/2003 |

| 6. Patient’s consent is mandatory in case of his/her participation in clinical medical education and scientific research. | article 19, Law no. 46/2003 |

|

|

|

|

| Insurance Clause |

|---|

|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bîrsanu, S.-E.; Plaiasu, M.C.; Nanu, C.A. Informed Consent in Mass Vaccination against COVID-19 in Romania: Implications of Bad Management. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1871. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10111871

Bîrsanu S-E, Plaiasu MC, Nanu CA. Informed Consent in Mass Vaccination against COVID-19 in Romania: Implications of Bad Management. Vaccines. 2022; 10(11):1871. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10111871

Chicago/Turabian StyleBîrsanu, Sînziana-Elena, Maria Cristina Plaiasu, and Codrut Andrei Nanu. 2022. "Informed Consent in Mass Vaccination against COVID-19 in Romania: Implications of Bad Management" Vaccines 10, no. 11: 1871. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10111871

APA StyleBîrsanu, S.-E., Plaiasu, M. C., & Nanu, C. A. (2022). Informed Consent in Mass Vaccination against COVID-19 in Romania: Implications of Bad Management. Vaccines, 10(11), 1871. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10111871